Loosely defined as the adequacy of resources to satisfy consumption needs in later life, old-age financial security is derived from three sources: oneself, the family, and the state (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mason and Miller2003; Witvorapong, Reference Witvorapong2015). The first source, denoted henceforth as self-reliance, refers to the accumulation of savings in the pre-retirement period and the receipt of interest payments or pension in the post-retirement period. The second and the third sources, denoted henceforth as family support and government support, refer to all forms of intra-household (private) transfers and government (public) transfers in the post-retirement period, respectively. An important difference between the three sources lies with the fact that self-reliance is a function of one's efforts during the working ages while the same is not necessarily true for family and government support.

Consistent with the life cycle hypothesis, whereby individuals maximize lifetime utility by stabilizing their consumption levels over time (Scholz et al., Reference Scholz, Seshadri and Khitatrakun2006; Binswanger and Schunk, Reference Binswanger and Schunk2012), this study hypothesizes that self-reliance, family support, and government support substitute each other in old age and this substitutability impacts the decision to save during the working ages. More specifically, if the size of old-age family and/or government support is expected to be sufficiently large, then individuals are likely to rely less strongly on themselves in old age and save less during the working ages in order to increase the level of lifetime consumption and utility.

The hypothesis is based on existing evidence. The literature often operationalizes self-reliance as pre-retirement savings, family support as transfers from one's adult children, and government support as the existence of a formal social safety net (e.g., welfare programs and direct public transfers). Studies suggest that old-age self-reliance and family support are substitutable. Galasso et al. (Reference Galasso, Gatti and Profeta2009), Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Mason and Miller2003), and Schultz (Reference Schultz2005) argue that the incentive to save for old age decreases in the presence of children because children serve as an intertemporal good that is invested by parents today and yields benefits (through filial transfers) tomorrow, representing a credible form of old-age insurance. The substitutability between pre-retirement savings and the presence of children has been empirically tested. For example, Choukhmane et al. (Reference Choukhmane, Coeurdacier and Jin2013) show that 30–60% of the rise in aggregate savings in China in 1982–2014 was attributable to the country's one-child policy, which reduced the average number of children per household. With regard to government assistance in old age, studies are relatively sparse but nonetheless indicate that, in general, government support crowds out pre-retirement savings. Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Mason and Miller2003), for example, suggest (indirectly) that the presence of a social support system reduces personal savings in Taiwan and the USA.

The substitutability between pre-retirement savings, on the one hand, and expected old-age family and government support, on the other, is likely to be more strongly felt in middle- and low-income countries (LMICs) (Schultz, Reference Schultz2005; Galasso et al., Reference Galasso, Gatti and Profeta2009; Choukhmane et al., Reference Choukhmane, Coeurdacier and Jin2013). Compared to high-income countries, capital markets in LMICs are less fully developed. Returns on financial products (reaped in old age) are more likely to be unreliable and unprotected (Galasso et al., Reference Galasso, Gatti and Profeta2009). This provides people with a comparatively stronger incentive to tighten their intertemporal budget constraints and rely on transfer wealth.

Based on a unique, nationally representative dataset of working-age individuals (18–59 years old) from Thailand, this study investigates the extent to which expectations for family support and state support in post-retirement years crowd out pre-retirement savings. It offers the following contributions. First, while existing studies use the actual presence of children or a formal government support system to represent old-age family and state support (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mason and Miller2003; Motel-Klingebiel et al., Reference Motel-Klingebiel, Tesch-Roemer and von Kondratowitz2005; Schultz, Reference Schultz2005; Galasso et al., Reference Galasso, Gatti and Profeta2009; Choukhmane et al., Reference Choukhmane, Coeurdacier and Jin2013), this study exploits information on expectations for potential financial sources in old age in the dataset and is able to test how future expected transfer wealth impacts the decision to save today. Also, this study uses data that represent the working-age population. It differs from existing studies on retirement planning which are based either on a sample of younger individuals (e.g., Finke and Huston Reference Finke and Huston2013; Nosi et al., Reference Nosi, d'Agostino, Pagliuca and Pratesi2014) who may not be able to comprehend the importance of retirement planning, or near-old or older individuals (e.g., Scholz et al., Reference Scholz, Seshadri and Khitatrakun2006; Hurd et al., Reference Hurd, Duckworth, Rohwedder and Weir2012) who are probably already past the planning stage. Finally, this study is the first to use data from Thailand, an upper-middle-income country in Asia. It is different from existing studies of saving behaviors, which are often based on high-income countries (Scholz et al., Reference Scholz, Seshadri and Khitatrakun2006; Binswanger and Carman, Reference Binswanger and Carman2012; Binswanger and Schunk, Reference Binswanger and Schunk2012; Finke and Huston, Reference Finke and Huston2013; Nosi et al., Reference Nosi, d'Agostino, Pagliuca and Pratesi2014; Alan et al., Reference Alan, Atalay and Crossley2015). The importance of context-specific discoveries is highlighted in the literature. For instance, in their comparative analyses of European countries and Israel, Motel-Klingebiel et al. (Reference Motel-Klingebiel, Tesch-Roemer and von Kondratowitz2005) illustrate that the level of substitutability (or lack thereof) between family support and state support varies across countries, suggesting that lessons from one setting are not necessarily generalizable to others.

The remainder of the paper begins with background information on old-age security in Thailand, followed by the description of data and empirical methods used in the study, results and, finally, conclusions.

1. Background information

The landscape of old-age security in Thailand is composed of the pension system (representing self-reliance), the provision of old-age health insurance and monthly allowances by the government (representing government support), and the availability of kin networks (representing family support). This section describes each of the three components.

The design of the Thai pension system is rooted in the heterogeneity within the labor market. Accounting for 3.3% of the population or 5.6% of the workforce in 2015 (OCSC, 2016), civil servants are entitled to receive an earnings-related pension at the mandatory retirement age of 60. Civil servants entering public service after 27 March 1997 are required to contribute 3% of their monthly income to the Government Pension Fund, with a top-up of the same amount from the government, while those having served the government since before the cut-off date have two options: to participate in the Government Pension Fund or to choose a non-contributory defined-benefit pension plan that is available exclusively to them (FPO, nd).

Non-government employees in the formal sector (i.e., working in private enterprises and receiving a constant stream of taxable income) are entitled to receive an earnings-related pension under the Social Security system. The Social Security system provides employment-related benefits, e.g., health and invalidity benefits, and also operates the Old Age Pension Fund. Participation in Social Security, and extensionally the Old Age Pension Fund, is compulsory for all private-sector firms with at least one employee on the payroll (Supakankunti and Witvorapong, Reference Supakankunti, Witvorapong, Aspalter, Pribadi and Gauld2017). It requires tripartite contributions specifically to the Old Age Pension Fund from employees, employers and the government of the amount equivalent to 3%, 3%, and 1% of each employee's monthly income respectively. Currently, 17.3% of the population are covered under the system (MOPH, 2019).

In addition, the retirement savings of income-earners in the formal private sector can be further accumulated through what is known as a Provident Fund (SET, 2015). With optional participation, the Fund is a long-term savings program that is independently set up and sponsored by private-sector employers. Participating employees contribute between 2 and 15% of their monthly salary. The appeal stems from the fact that (1) contributions to the Fund are tax-deductible as long as, when combined with other forms of tax-deductible investments, they do not exceed the upper threshold of 500,000 Thai baht (THB) per year and (2) they are matched by employers and credited directly to the employee's individual account. The Fund is managed by a private asset management company and is invested in a range of financial instruments.

There is no mandatory retirement age in the formal private sector. Nevertheless, from the age of 55, pension benefits from the Old Age Pension Fund can be reaped, and returns from the Provident Fund can be withdrawn without being subjected to tax. Also, according to the Labor Protection Act (No.6) B.E. 2560 (2017), it is legally permissible for private-sector employees to terminate their own employment by submitting a letter of intent to retire once they reach the age of 60.

The rest of the labor market is made up of informal and self-employed workers, who together constitute between 50% and 75% of the workforce (Buddhari and Rugpenthum, Reference Buddhari and Rugpenthum2019). Albeit not subjected to a mandatory pension scheme, informal and self-employed workers have two options to attain an old-age pension. One is to subscribe to Social Security for a monthly fee and enjoy benefits similar to what is available to formal-sector workers, which include inter alia earnings-related old-age pension. The other is to join the National Savings Fund and contribute (with top-up from the government) between 50 and 13,200 THB (US$1.5–400, at the exchange rate of US$1: 33 THB) per annum until the age of 60 (NSF, nd). Nevertheless, the take-up rate for both options has remained low. In 2019, the proportion of informal workers who were members of the National Savings Fund was around 11.4% (NSF, 2020).

In addition to savings and pensions accumulated during the working ages, all Thai nationals are eligible to receive old-age government support. The government provides access to health services to the older population at little to no cost (Supakankunti and Witvorapong, Reference Supakankunti, Witvorapong, Aspalter, Pribadi and Gauld2017). Retired civil servants are provided with a health insurance coverage under the Civil Service Medical Benefit Scheme, while retired formal-sector employees and informal workers are covered under the Universal Coverage Scheme. Both schemes offer a comprehensive benefit package without imposing any copayment. The Thai government also provides Old Age Allowance universally. All persons aged 60–69, 70–79, 80–89 and 90 or older are entitled to receive 600 THB (US$20), 700 THB (US$23), 800 THB (US$26) and 1,000 THB (US$33) per month respectively (Suwanrada and Leetrakul, Reference Suwanrada and Leetrakul2014).

The final source of old-age security is the family. Evidence suggests that adult children represent an important financial source for older Thais (Witvorapong, Reference Witvorapong2015). According to a national survey in 2017, the overwhelming majority (86%) of older Thai parents reported having received monetary transfers from their children, with 38% identifying adult children as the main income source. The same survey suggests that such transfers take place constantly, as most older persons (two-thirds) reported co-residing with their children (Teerawichitchainan et al., Reference Teerawichitchainan, Pothisiri, Knodel and Prachuabmoh2019). A unique feature of the Thai family dynamics is the fact that family members, other than adult children, may also provide support to older persons. In a different survey conducted by the National Statistical Office in 2011, it was reported that 38.2% of the Thai population expected their relatives (as opposed to immediate family members) to financially assist them in old age. This suggests that the definition of ‘family support’ in the Thai context may encompass more than upstream transfers from children.

The above description illustrates that different sources of financial support are available to the older population in Thailand. Regardless of their occupations, all working-age Thais have an opportunity to be self-reliant, provided with infrastructure and an incentive to save for retirement and enjoy a pension. Once they transition into old age, they are provided with a formal source of financial support in the form of government-sponsored old-age allowances, and may also receive an informal source of support from adult children and/or other family members. This suggests that the three sources of financial security, namely, self-reliance, government support, and family support, are available to a given Thai older person, and it is an empirical question as to whether these sources complement or compete with each other.

2. Data and empirical strategy

2.1 Data

This study draws from the 2011 Survey of Knowledge and Attitudes on Elderly Issues. Based on a three-stage stratified sampling design, the survey was jointly conducted by the National Statistical Office, the College of Population Studies at Chulalongkorn University, and the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security. After removing observations with inconsistent responses (99 observations), the final sample contains 8,901 observations. It constitutes a nationally representative sample of the Thai working-age population (defined as individuals aged between 18 and 59).

2.2 Measures

The outcome variable is pre-retirement savings, denoted by SAV i. It is based on the question: ‘Have you prepared yourself financially, including saving money and accumulating assets, for old age?’. The variable SAV i takes the value of 1 if individual i responded yes to the question and 0 otherwise.

The main explanatory variables are twofold. Denoted by NSelf i, financial non-self-reliance is based on the question: ‘Which of the following financial sources do you think you could rely on when you become old?’. Respondents were allowed to identify one or more of the eight possible responses: own income, spouse's income, children, grandchildren, relatives, own wealth (savings or assets), own pension, and the government. Four of the responses, including own income, spouse's income, own wealth, and own pension, are deemed to be indicative of ‘self-reliance’ in old age.Footnote 1 The variable NSelf i is assigned the value of 1 if none of the self-reliance responses was selected (and one or more of the remaining possible responses were selected), and the value of 0 if individual i chose any of the four self-reliance responses.

The distinction between ‘non-self-reliance’ (NSelf i = 1) and ‘self-reliance’ (NSelf i = 0) can be alternatively explained. While ‘non-self-reliance’ refers to the expectation that none (0%) of the required financial resources in old age would come from oneself, ‘self-reliance’ does not necessarily imply the extreme opposite, that is, total self-dependence (100%). Instead, it represents the expectation that some or all (>0%) of the financial resources needed in old age would be provided by oneself.

The other main explanatory variable is the identification of the most important source of old-age financial security. It is based on the question: ‘Which of the following financial sources do you think would be most important to you when you become old?’. The same possible responses described in the preceding paragraph applied and respondents were required to choose only one. In the empirical strategy, the possible responses are categorized into three non-overlapping groups. The omitted group includes respondents who chose any of the self-reliance responses as their most important source of old-age financial security. The other two groups represent those who considered family support and government support to be their most important financial source in old age, denoted by $Fam\_M_i$![]() and $Gov\_M_i$

and $Gov\_M_i$![]() , respectively. The variable $Fam\_M_i$

, respectively. The variable $Fam\_M_i$![]() takes the value of 1 if individual i identified his/her children, grandchildren, or relatives to be the most important financial source in old age, and 0 otherwise. The variables $Gov\_M_i$

takes the value of 1 if individual i identified his/her children, grandchildren, or relatives to be the most important financial source in old age, and 0 otherwise. The variables $Gov\_M_i$![]() are assigned the value of 1 if individual i identified the government as his/her most important source of old-age financial security.

are assigned the value of 1 if individual i identified the government as his/her most important source of old-age financial security.

The interaction terms between the two main explanatory variables are also explored. Since there are two categories for non-self-reliance (i.e., NSelf i = 0 and NSelf i = 1) and three categories for the most important source of old-age financial security (i.e., $Fam\_M_i$![]() = 1, $\;Gov\_M_i$

= 1, $\;Gov\_M_i$![]() = 1, and the omitted category of self-reliance), on the surface, it would seem feasible to create 3 × 2 = 6 mutually exclusive interaction terms. However, the interaction term between NSelf i = 1 and the omitted category of self-reliance as the most important financial source is unattainable – practically because its construction yields no observations, and intuitively because it would refer to the presence of an individual who does not think of him/herself as a reliable source of old-age finances yet identifies him/herself as the most important financial source in old age. Therefore, there are only five interaction terms. The variable $SF\_M_i$

= 1, and the omitted category of self-reliance), on the surface, it would seem feasible to create 3 × 2 = 6 mutually exclusive interaction terms. However, the interaction term between NSelf i = 1 and the omitted category of self-reliance as the most important financial source is unattainable – practically because its construction yields no observations, and intuitively because it would refer to the presence of an individual who does not think of him/herself as a reliable source of old-age finances yet identifies him/herself as the most important financial source in old age. Therefore, there are only five interaction terms. The variable $SF\_M_i$![]() takes the value of 1 if individual i expected to be self-reliant and identified the family as the most important financial source in old age. The variable $SG\_M_i$

takes the value of 1 if individual i expected to be self-reliant and identified the family as the most important financial source in old age. The variable $SG\_M_i$![]() takes the value of 1 if individual i expected to be self-reliant and identified the government as the most important financial source in old age. The variables $NSF\_M_i$

takes the value of 1 if individual i expected to be self-reliant and identified the government as the most important financial source in old age. The variables $NSF\_M_i$![]() and $NSG\_M_i$

and $NSG\_M_i$![]() are assigned the value of 1 if individual i expected to be non-self-reliant and identified the family and the government to be the most important financial source in old age, respectively. The fifth interaction term is the omitted category, including individuals who expected to be self-reliant and identified themselves as the most important financial source in old age.

are assigned the value of 1 if individual i expected to be non-self-reliant and identified the family and the government to be the most important financial source in old age, respectively. The fifth interaction term is the omitted category, including individuals who expected to be self-reliant and identified themselves as the most important financial source in old age.

2.3 Empirical Model

To examine the relationship between the decision to save for retirement during the working ages and expected sources of post-retirement financial security, three regression specifications are used. Based on a probit model, the first specification takes the following form:

$\hskip-1pcSAV_i^\ast$![]() denotes the latent variable of pre-retirement savings, SAV i. The explanatory variable of interest is NSelf i, referring to the expectation for financial non-self-reliance in old age. It is hypothesized that α be negative, consistent with the fact that pre-retirement savings and sources of old-age financial security other than oneself have been shown to be substitutable (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mason and Miller2003; Schultz, Reference Schultz2005; Galasso et al., Reference Galasso, Gatti and Profeta2009; Choukhmane et al., Reference Choukhmane, Coeurdacier and Jin2013).

denotes the latent variable of pre-retirement savings, SAV i. The explanatory variable of interest is NSelf i, referring to the expectation for financial non-self-reliance in old age. It is hypothesized that α be negative, consistent with the fact that pre-retirement savings and sources of old-age financial security other than oneself have been shown to be substitutable (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mason and Miller2003; Schultz, Reference Schultz2005; Galasso et al., Reference Galasso, Gatti and Profeta2009; Choukhmane et al., Reference Choukhmane, Coeurdacier and Jin2013).

Vector xi represents a deliberately chosen set of individual/household characteristics. It includes variables that have been shown to be statistically important in explaining saving behaviors, including gender, age, education, marital status, income, and household structure (Binswanger and Carman, Reference Binswanger and Carman2012; van Rooij et al., Reference van Rooij, Lusardi and Alessie2012; Finke and Huston, Reference Finke and Huston2013; Nosi et al., Reference Nosi, d'Agostino, Pagliuca and Pratesi2014; Alan et al., Reference Alan, Atalay and Crossley2015). It also includes whether the individual worked in the formal or the informal sector, as the variable indicates the potential existence of an old-age pension in Thailand. Altogether, the vector captures each individual's constraint as well as their ability to predict future consumption trajectories and foresee how much they need to save today in order to optimize their lifetime living standards.

The second probit regression specification is given by:

The variables $SAV_i^\ast$![]() and xi are similarly defined. The variable NSelf i is replaced by $Fam\_M_i$

and xi are similarly defined. The variable NSelf i is replaced by $Fam\_M_i$![]() and $Gov\_M_i$

and $Gov\_M_i$![]() , which represent whether individual i expected family support and government support to be their most important financial source in old age, respectively. The reference category is self-support as the most important financial source in post-retirement years. It is hypothesized that both β 1 and β 2 be negative; the probability of saving for retirement is likely to be lower among individuals who expect their family and the government to be more important than themselves as a source of old-age financial security.

, which represent whether individual i expected family support and government support to be their most important financial source in old age, respectively. The reference category is self-support as the most important financial source in post-retirement years. It is hypothesized that both β 1 and β 2 be negative; the probability of saving for retirement is likely to be lower among individuals who expect their family and the government to be more important than themselves as a source of old-age financial security.

The third specification is given by:

The variables of interest are $SF\_M_i$![]() , $SG\_M_i$

, $SG\_M_i$![]() , $NSF\_M_i$

, $NSF\_M_i$![]() , and $NSG\_M_i$

, and $NSG\_M_i$![]() . Defined in the ‘Measures’ sub-section, they represent the interaction terms between NSelf i, on the one hand, and $Fam\_M_i$

. Defined in the ‘Measures’ sub-section, they represent the interaction terms between NSelf i, on the one hand, and $Fam\_M_i$![]() and $Gov\_M_i$

and $Gov\_M_i$![]() , on the other. The omitted category is when the individual expected to be self-reliant and identified themselves as the most important financial source in old age. Consistent with the discussion for Specifications 1–2, the coefficients γ 1 − γ 4 are hypothesized to be negative.

, on the other. The omitted category is when the individual expected to be self-reliant and identified themselves as the most important financial source in old age. Consistent with the discussion for Specifications 1–2, the coefficients γ 1 − γ 4 are hypothesized to be negative.

The main explanatory variables in Specifications 1–3 are potentially endogenous. In addition to the problem of reverse causality, the presence of common unobserved heterogeneity represents another source of estimation bias. The literature suggests that time and risk preferences (Bernheim et al., Reference Bernheim, Skinner and Weinberg2001; Binswanger and Carman, Reference Binswanger and Carman2012; van Rooij et al., Reference van Rooij, Lusardi and Alessie2012; Finke and Huston, Reference Finke and Huston2013) as well as personality traits (Hurd et al., Reference Hurd, Duckworth, Rohwedder and Weir2012) determine pre-retirement decisions and may contemporaneously influence how individuals identify their source of financial security in the future. Nevertheless, these variables are difficult to measure in a national survey and are missing in the data used in this study.

Recursive multivariate probit modeling is used to account for potential endogeneity bias in all of the above specifications. For illustration purposes, based on Specification 3, the model jointly estimates the following five probit equations:

where

Vector z i represents instrumental variables (IVs). It is included in the equations for the ‘endogenous’ regressors (i.e., equations (2–5)) but excluded in the main regression (i.e., equation (1)). The error terms are assumed to follow a five-dimensional standard normal distribution. The expected value and the variance for each error term are 0 and 1, respectively. As shown in the variance-covariance matrix, there are 10 unique covariances (ρ), one for each pair of the error terms. Given the joint probability density function, the model is estimated using a simulated maximum likelihood estimator (MLE).

The validity of the IVs is tested with a simple over-identification test. Endogeneity bias is assessed through tests of the covariance between the error terms in equations (1) and (2) (ρ 12), between equations (1) and (3) (ρ 13), between equations (1) and (4) (ρ 14), and between equations (1) and (5) (ρ 15). Assuming that the IVs are valid, statistical insignificance of the covariances would indicate the lack of evidence supporting the presence of unobserved common factors and endogeneity bias in the system of equations (Monfardini and Radice, Reference Monfardini and Radice2008).

The recursive multivariate probit approach is chosen deliberately. Lewbel et al. (Reference Lewbel, Dong and Yang2012) identify four ‘convenient’ (i.e., readily implementable) estimators that can be used to measure the effect of endogenous regressors in binary choice models: two-stage least squares linear probability models (2SLS-LPM), MLE, control function estimators, and special regressor models. Recursive multivariate probit modeling falls within the MLE category. The control function and the special regressor approaches are not applicable to this study. The identification of the former relies on specific functional forms and requires that the endogenous regressors be continuously distributed, which stands in contrast with the discrete nature of the endogenous regressors here. The identification of the latter requires the existence of an exogenous regressor that is continuous with a large support and preferably a thick-tailed distribution. As shown in Table 1 below, it is not possible to identify such regressor in the data; most of the regressors are discrete and the support of the few continuous regressors that are available is limited, having small variances.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and tests of equality of pre-retirement saving proportions (N = 8,901)

Notes: [Ref.] = Reference category; ***, **, * = 1, 5, and 10% of level of significance respectively; test statistics in column III refer to χ2 tests for equality of proportions, unless otherwise stated.

Source: Authors' calculation from the 2011 Survey of Knowledge and Attitudes on Elderly Issues.

The other two estimators, including 2SLS-LPM and MLE, can be used. In reference to Specification 3, the 2SLS-LPM approach treats the main discrete variables as if they were linear, using actual (instead of latent) variables of SAV i, $SF\_M_i$![]() , $SG\_M_i$

, $SG\_M_i$![]() , $NSF\_M_i$

, $NSF\_M_i$![]() , and $NSG\_M_i$

, and $NSG\_M_i$![]() . In the first stage, equations (2–5) are (separately) estimated with IVs zi. In the second stage, equation (1) is estimated, with the first-stage predicted values being used in place of the endogenous regressors. The approach does not use information in the first-stage error terms, assuming that they are unrelated to the error term in the second stage. An important disadvantage of the approach is that fitted probabilities may be below 0 or above 1.

. In the first stage, equations (2–5) are (separately) estimated with IVs zi. In the second stage, equation (1) is estimated, with the first-stage predicted values being used in place of the endogenous regressors. The approach does not use information in the first-stage error terms, assuming that they are unrelated to the error term in the second stage. An important disadvantage of the approach is that fitted probabilities may be below 0 or above 1.

It is argued that the MLE approach, which encompasses recursive multivariate probit modeling, is more appropriate than 2SLS-LPM. It estimates equations (1–5) simultaneously through a known joint distribution of the error terms. The method is considered more efficient than 2SLS-LPM as it requires more information (Lewbel et al., Reference Lewbel, Dong and Yang2012), exploiting the covariances of the error terms to obtain more precise estimates. Also, unlike 2SLS-LPM, it does not produce out-of-range probability values. It should be noted that the identification of the MLE approach is derived from two sources: the use of IVs and the functional form. With regard to the latter, Wilde (Reference Wilde2000) argues that, as long as there is a varying exogenous regressor in all equations of the model (i.e., there is sufficient variation in the data), the nonlinearity of the model alone is sufficient for identification and no exclusion restrictions are needed. A more recent article by Li et al. (Reference Li, Poskitt and Zhao2019) elaborates on the issue by specifying the conditions under which identification by functional form is appropriate.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 represents summary statistics and test statistics for the equality of pre-retirement saving propensities across personal and household characteristics. Column I shows the proportion or the mean of variables in the model. Column II shows the proportion of the sample with pre-retirement savings by personal/household characteristics. Column III shows whether the proportions in Column II differ statistically within a given characteristic. Chi-square tests for equality of proportions are used for binary and categorical characteristics, and, for continuous variables, pairwise correlation coefficients are calculated and tested with Bonferroni-adjusted significance levels.

The majority of the sample (58.6%) reported currently saving for retirement. Almost all respondents (96.6%) expected to be able to rely on themselves (partially or fully) in post-retirement years. A small portion of the sample (3.4%) reported being non-self-reliant, expecting either the family or the government to financially support them in old age. The proportions of respondents with expectations for financial self-reliance and non-self-reliance who had pre-retirement savings (Column II) were 59.2% and 38.4%, respectively. The two proportions were statistically different.

When asked about the most important source of financial security in post-retirement years, 61.0% of the sample identified themselves, while 34.8% and 4.2% identified the family and the government, respectively. Among respondents who expected themselves to be the most important source of old-age financial security, the proportion with pre-retirement savings (Column II) was 61.1%. This was notably different from the ratios among respondents who expected their family (54.0%) and the government (59.0%) to be the most important provider in old age.

Combining information on whether one expected to be self-reliant and that on the most important source of old-age financial security revealed that most respondents expected to be self-reliant and identified themselves as the most important old-age financial source (61.0%). Respondents who expected to be self-reliant yet identified the family and the government to be the most important financial source made up 32.0% and 3.6% of the sample, respectively. Those who expected not to rely on themselves and identified the family and the government to be the most important financial source made up 2.8% and 0.5%, respectively. Regardless of which financial source was considered most important, more than half of respondents who expected to be self-reliant had pre-retirement savings (Column II). It was statistically different from the ratios (39.6% and 32.7%) among those who expected to be non-self-reliant.

The majority of respondents were female (53.6%), were 35–44 years old (29.2%), had secondary education (43.2%), were currently married (62.3%), were employed in the informal sector (54.4%), and were relatively poor with a monthly household income of less than 10,000 THB (43.9%), equivalent to approximately US$300. The average household size was 3.96. Older adults (more than 60 years old) made up about 11.1% of an average working-age household, and the number of children per household was approximately 0.66. The majority of the sample reported wanting more children (57.6%) and lived in a non-municipal area (55.5%). With the exception of the location of residence, the proportions of respondents with pre-retirement savings statistically differed across characteristics. Working-age individuals who were female, older, more highly educated, married, formally employed, and economically better off showed greater propensities to save toward retirement. Households with more members, a larger proportion of older members, more children, and an interest in having more children demonstrated statistically higher saving propensities.

Relationships between the main explanatory variables and selected personal/household characteristics are shown in Table A.1 in the Appendix. The table contains information similar to Columns II and III of Table 1 and suggests that the proportions of respondents who expected to be non-self-reliant and those identifying either themselves or their family or the government as the most important source of old-age finances varied statistically across characteristics. Compared to their respective counterparts, lower proportions of respondents who were female, less well-educated, unemployed, and had less income expected to be self-reliant and identified themselves as the most important financial source in old age, while higher proportions of the same groups identified their family as the most important source. The pattern for the identification of the government as the most important financial source was less clear. The results suggest that, compared to those in a higher socioeconomic bracket, working-age adults with a lower socioeconomic status had greater expectations for family support and were more likely to expect that they would not be able to support themselves.

3.2 Regression results: full sample

Table 2 shows marginal effects of the main regressors from six probit models. In addition to personal and household characteristics, all six models in Table 2 control for regional fixed effects. The purpose is to capture missing region-level characteristics that may influence saving behaviors (e.g., the availability of retirement-saving instruments and the number of commercial banks), which vary from one region to another. The marginal effects are paired with heteroskedasticity-adjusted individual-level Huber-White standard errors, calculated with the delta method.

Table 2. Marginal effects of main regressors from probit and recursive multivariate probit regressions of saving behavior (N = 8,901)

Notes: MV-probit = recursive multivariate probit; heteroskedasticity-adjusted standard errors calculated with the delta method in parentheses; ***, **, * = 1, 5 and 10% of level of significance respectively.

Source: Authors' calculation from the 2011 Survey of Knowledge and Attitudes on Elderly Issues.

Models 1–2 are based on Specification 1, Models 3–4 on Specification 2, and Models 5–6 on Specification 3. Models 1, 3, and 5 represent single-equation probit regressions that do not account for potential endogeneity bias. Models 2, 4, and 6, on the other hand, refer to recursive multivariate probit regressions based on a simulated maximum likelihood approach with 100 pseudo-random draws, where potential endogeneity bias is explicitly tackled. Under Model 2, the main equation (saving behavior) and one other probit regression whose dependent variable is the potentially endogenous regressor (i.e., non-self-reliance) in the main equation are jointly estimated. The same logic applies for Models 4 and 6, where the number of jointly estimated equations is (3) and (5), respectively. Table 2 shows only the main regressors. Marginal effects of personal and household characteristics are provided in Table A.2 in the appendix. Both Table 2 and Table A.2 leave out estimates for the endogenous regressors for Models 2, 4, and 6 and focus on the savings regressions to conserve space. The full model estimates are available upon request.

To estimate the recursive multivariate probit models, IVs are identified. The number of IVs for all three models (Models 2, 4, and 6) is four. They refer to village-level ratios of people who agreed with each of the following statements: (1) ‘Older people are outdated’; (2) ‘Older people should not live with their family’; (3) ‘Older people do not set good examples for the younger generations’; and (4) ‘Older people do not have important social roles’. The dataset contains 90 uniquely identified village clusters, with approximately 10 observations in each cluster. These IVs satisfy the exogeneity requirement of valid IVs in that they explain the dependent variable (i.e., pre-retirement savings) only through the potentially endogenous regressors. They capture area-specific (as opposed to individual-specific) attitudes of the working-age population toward older people. These ‘public’ attitudes likely impact how individuals foresee their roles and values in relation to others (i.e., family members and the state) when they become older (Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Witvorapong and Pothisiri2017), indirectly influencing the probability of saving for retirement.

3.2.1 Endogeneity tests

To compare Model 1 against Model 2, Model 3 against Model 4, and Model 5 against Model 6 requires endogeneity tests. They are performed through the recursive multivariate models. The process involves several steps. First, the validity of the above IVs is tested. Simple over-identification tests are undertaken and the results are shown in Table A.3 in the Appendix. Based on χ2 tests of joint significance, the selected IVs are shown not to be statistically significant in the saving behavior equations in Models 2, 4, and 6. They are also shown to be collectively statistically significant in the regressions for the potentially endogenous regressors. The over-identification tests provide support for the chosen IVs, suggesting that they explain the endogenous regressors sufficiently and do not directly explain the dependent variable.

The bottom part of Table 2 shows covariances of all possible pairs of the error terms under Models 2, 4, and 6. It can be seen that the covariance between the error term of the saving behavior equation and that of each of the equations for the main regressors is not statistically significant in any of the models. In fact, recursive multivariate probit models without the above exclusion restrictions are also performed and the exercise (Table A.4 in the Appendix) shows similarly that the covariance between the error terms of the saving behavior equation and each of the main regressors is not statistically significant in any of the specifications. This suggests (1) that there is not enough evidence to suggest the existence of common unobserved factors between saving behavior and expectations for sources of post-retirement financial security; (2) that these equations should be separately (rather than jointly) modeled; and (3) that there is not enough evidence to conclude that the ‘potentially’ endogenous regressors are endogenous (Monfardini and Radice, Reference Monfardini and Radice2008).

3.2.2 Alternative modeling methods as robustness checks

To ensure that endogeneity does not pose a problem, robustness checks are performed using two other tests of exogeneity. First, Smith-Blundell tests are undertaken for all three specifications, assuming that the potentially endogenous regressors can be linearly approximated, incorporating the above IVs. The results show that the exogeneity assumption cannot be rejected; the χ2 values from the tests are statistically insignificant at 3.458, 2.547, and 4.433 for Specifications 1–3 respectively. Second, two-stage least squares linear probability models (2SLS-LPM) with Huber-White standard errors are explored. Again, consistent with the recursive multivariate probit models and the Smith-Blundell tests, there is not enough evidence to reject exogeneity of the main regressors. The Durbin χ2 values are not statistically significant, being equal to 3.139, 2.267, and 4.178 for Specifications 1–3 respectively.Footnote 2 The empirical analyses thus far show no evidence of endogeneity. The conclusion is robust to modeling techniques (probit versus LPM), types of endogeneity test (covariance tests versus Smith-Blundell tests versus Durbin-Wu-Hausman tests), and estimation methods (maximum likelihood versus least squares).

3.2.3 Model interpretation

Even though the above discussion consistently suggests that endogeneity bias is not a problem, the credibility of the conclusion relies on the IVs. As shown in Table A.3, the IVs in this study are valid when they are considered jointly but not necessarily when they are considered separately, calling into question the degree in which they are valid. Also, as discussed at length by Lewbel et al. (Reference Lewbel, Dong and Yang2012), the MLE method (which encompasses recursive multivariate probit modeling) is particularly sensitive to the choice of IVs; it is possible that an alternative set of IVs may produce a different conclusion. In light of the imperfections of the identification strategy, the discussion below takes a conservative approach and considers models with and without endogeneity correction together. Nevertheless, a greater emphasis is placed on those assuming exogeneity.

In Table 2, Models 1, 3, and 5 are models without endogeneity correction. Model 1 demonstrates that all else equal, individuals who expected to be non-self-reliant in post-retirement years had a 16.9% lower probability of saving for retirement. Model 3 shows that individuals who considered their family to be the most important financial source in old age had a 6.5% lower probability of saving for retirement, compared to those who thought of themselves as the primary source. Expectations that government support would be the most important financial source had no impact on saving behaviors. Finally, Model 5 suggests that individuals who expected to be self-reliant and considered their family to be the most important financial source in old age were 5.6% less likely to save, compared to those who expected to be self-reliant and identified themselves as the most important source. Also, individuals who expected to be non-self-reliant and identified their family and the government as the most important source of old-age financial security were 17.4% and 26.7% less likely to save for retirement, respectively. The only group that showed saving patterns that were not statistically different from the reference group consisted of individuals who expected to be self-reliant and identified the government as the most important provider in old age.

Models 2, 4, and 6, which endogenize the main regressors, produce some of the same results. They differ from the above models in that they suggest that non-self-reliance is not an important determinant of the probability of saving for retirement, yet they demonstrate, similarly to the above models, that identifying family as the most important source of old-age financial security reduces the probability to save for retirement overall, and does so particularly when it is combined with non-self-reliance. This suggests that anticipation for family support in old age replaces the propensity to save during the working ages in the Thai context.

With regard to personal/household characteristics (Table A.2), all models provide similar conclusions. They suggest that being female, older, more educated, employed in the formal sector, richer, and resident of a municipal area are positively associated with the probability of saving for retirement. Household composition (proxied by the number of children and the presence of older adults in the household) is found to influence pre-retirement savings only weakly.

Altogether, the analysis offers three main conclusions. First, expectations for non-self-reliance seem to crowd out the probability of saving for retirement. Second, expectations that one's own family would be the most important source of old-age financial security crowd out the probability of saving for retirement. Finally, expectations that the government would be the most important source of old-age financial security do not impact the probability of saving for retirement in general. The exception lies with Model 5, where it is found that individuals who do not plan to rely on themselves and expect government support to be the predominant financial source in old age have the lowest probability of saving for retirement ceteris paribus.

3.3 Regression results: sub-samples

To further investigate the impact of future expected family and government support on the probability of saving for retirement, the full sample is divided into different sub-samples, following the likelihood-ratio Chow tests. Gender, age, education, work status, and income sub-samples are selected for further analyses. These variables directly impact the probability of saving for retirement (as shown in Table A.2), and may also impact retirement savings indirectly through unobserved heterogeneity. Gender, age, education, and income (as well as work status which is strongly associated with income) are known to influence the following unobserved factors for retirement savings: (1) time preferences (Bernheim et al., Reference Bernheim, Skinner and Weinberg2001; Binswanger and Carman, Reference Binswanger and Carman2012; van Rooij et al., Reference van Rooij, Lusardi and Alessie2012; Finke and Huston, Reference Finke and Huston2013; Nosi et al., Reference Nosi, d'Agostino, Pagliuca and Pratesi2014) and (2) tastes for savings, inclusive of retirement planning tendencies and annuitization propensities (Binswanger and Carman, Reference Binswanger and Carman2012; Nosi et al., Reference Nosi, d'Agostino, Pagliuca and Pratesi2014; Alan et al., Reference Alan, Atalay and Crossley2015). These characteristics have also been found to affect attitudes of the working-age population toward older people. Under the framework of the conflict perspective on aging, Yoon et al. (Reference Yoon, Witvorapong and Pothisiri2017) discuss the fact that working-age people in Thailand may ‘self-categorize’ against older people based exactly on these characteristics.

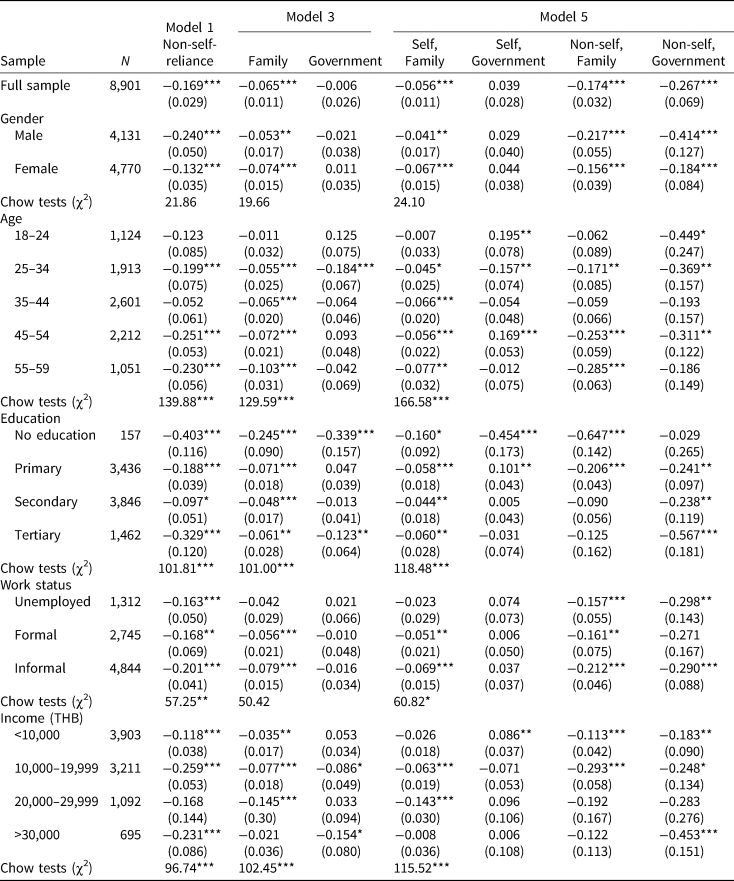

Table 3 shows marginal effects of the main regressors from Models 1, 3, and 5 (i.e., those without endogeneity correction). The Chow tests suggest that there is no evidence that the male and female sub-samples differ in any of the specifications and weak evidence that the work status sub-samples differ. However, there is evidence at the 1% level that the marginal effects differ across age, education, and income categories.

Table 3. Marginal effects from probit regressions of pre-retirement saving behavior based on full and disjointed samples (N = 8.901)

Notes: Heteroskedasticity-adjusted standard errors calculated with the delta method in parentheses; ***, **, * = 1, 5, and 10% of level of significance respectively.

Source: Authors' calculation from the 2011 Survey of Knowledge and Attitudes on Elderly Issues.

The discussion henceforth focuses on age, education, and income. Under Specification 1 (Model 1), expectations for non-self-reliance are associated rather linearly with age but non-linearly with education and income. The negative impacts of non-self-reliance are largest among individuals with no education, followed by those with tertiary education, and among individuals with monthly income of 10,000–19,000 THB, followed by those in the income category of >30,000 THB. Under Specification 2 (Model 3), the impacts of expectations for family support as the most important financial source vary quite linearly with age. Family support expectations crowd out the probability of saving for retirement most evidently among individuals with no education, and impact individuals across income groups heterogeneously, being statistically insignificant for the highest-income group, but significant for the lower-income groups. Under Specification 3 (Model 5), the impacts of non-self-reliance, as well as family and government support expectations, are consistent with the earlier discussion based on Specifications 1–2. The impacts of non-self-reliance, when combined with the identification of government support as the most important financial source, are larger among younger and better-educated individuals, in contrast with the impacts of family support, which are larger among older and less educated individuals.

Overall, Table 3 suggests financial non-self-reliance and sources of old-age financial security have differential impacts across population sub-groups. In general, expectations for non-self-reliance and/or the identification of family support as the most important financial source exert a larger negative impact among individuals who are older and less educated. The identification of government support as the most important source of old-age financial security exerts insignificant effects in general, but, when combined with non-self-reliance, impacts younger and better-educated individuals particularly strongly.

4. Conclusions

Based on the nationally representative 2011 Survey of Knowledge and Attitudes on Elderly Issues (N = 8,901), this study investigates the extent to which expectations of intra-family transfers and government assistance in old age impact the probability of saving for retirement among working-age individuals in Thailand. Three probit specifications are explored. The first specification includes expectations for financial non-self-reliance as the regressor of interest. The second specification includes expectations for family support and government support as the most important financial source as the main regressors. The final specification includes all possible combinations of the main regressors from the earlier specifications. Presence of potential endogeneity bias associated with the main regressors for each of the specifications is tested in a recursive multivariate probit model. The assumption of exogeneity cannot be rejected, given the choice of IVs used in the study.

The study offers several important conclusions. First, expectations to be financially non-self-reliant in old age decrease the probability of saving for retirement. The impacts are particularly strong among older (working-age) and less educated individuals. Second, in general, expectations of family support as the predominant source of old-age financial security reduce the probability of saving for retirement, compared to when self-support is considered the most important source. The crowding-out effects are again more strongly felt by older and less educated individuals. Finally, expectations that the government would be the most important source of old-age financial security neither discourage nor encourage the decision to save on average, yet they negatively influence the probability of saving for retirement among non-self-reliant individuals, impacting particularly younger and better-educated individuals.

The fact that expectations for non-self-reliance and expectations to rely predominantly on the family in old age separately and jointly crowd out the probability of saving is consistent with existing evidence. Witvorapong (Reference Witvorapong2015) shows that, in Thailand, adult children constitute the most important source of income in the majority of aged households. Yoon et al. (Reference Yoon, Witvorapong and Pothisiri2017), on the other hand, demonstrate that there is a sense of filial piety and the elders are still well-respected in the country. Both studies suggest that children serve as a form of old-age insurance in Thailand, and, in the socio-cultural context where anticipation for transfers from children is credible, future expected familial support often leads to lower savings today (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mason and Miller2003; Schultz, Reference Schultz2005; Choukhmane et al., Reference Choukhmane, Coeurdacier and Jin2013).

The fact that expected future government support does not impact the probability of saving for retirement is perhaps unsurprising. The Thai government provides a universal allowance in the range of 600–1,000 THB (equivalently US$20–35) per month as well as other forms of social support (e.g., public health insurance) for older people (Suwanrada, Reference Suwanrada2013; Suwanrada and Leetrakul, Reference Suwanrada and Leetrakul2014; Witvorapong, Reference Witvorapong2015). Given that there have not been major changes in the allowance amount since the policy's inception in 2009 and that the allowance makes up only about 10% of the average monthly income in the country (according to the National Statistical Office, the annual household income per capita was US$3,322.81 in 2017), it is not unrealistic to conjecture that the working-age population would expect government assistance in old age to be small, and would not change their saving behaviors in anticipation of future government assistance. In addition, a closer look at the data reveals that individuals in the poorest income category were the most likely to consider the government as the most important financial source. Among poorer individuals who do not have much to save, to begin with, it is unlikely that expectations for future government support would change their saving behaviors meaningfully.

Limitations exist in this study. First, the information contained in the dichotomous-dependent variable is limited. It would be ideal to use the amount (as opposed to the probability) of pre-retirement savings as the outcome variable, but such information is unavailable. Nevertheless, it is argued that the dependent variable is meaningful, compared to existing studies. It represents a decision, as opposed to a subjective evaluation of savings importance (Finke and Huston, Reference Finke and Huston2013) or hypothetically induced retirement-planning propensities (van Rooij et al., Reference van Rooij, Lusardi and Alessie2012). Second, the main regressors in this study are also discrete. It would be more informative to have information on the size of expected assistance in order to further unravel the complexity of the triangular relationships among self, family, and government support. Third, the study may be subjected to measurement error. The variables representing expectations for post-retirement financial sources may be inaccurately measured, given that they involve thinking about hypothetical situations in the future. In particular, younger respondents, who have not had much life experience, may find it difficult to answer survey questions about the future, lacking what Finke and Huston (Reference Finke and Huston2013) call ‘imagination capital’. Also, the main regressors may be susceptible to social desirability bias. It is possible that respondents hoping to rely on their family and the government in old age may not have reported the truth about their expectations because they did not want to appear vulnerable. Finally, despite the fact that endogeneity bias has been rigorously tested, the validity of the IVs remains questionable. Reverse causation that operates at the individual level is likely to also operate at the area level, challenging the exogeneity condition of the IVs which, in this case, are all village-based attributes. Nevertheless, it should be pointed out that this study follows existing research in using (average) area-specific characteristics as IVs (see, e.g., Ortega and Polavieja Reference Ortega and Polavieja2012) and that other studies have shown that estimation results, when endogeneity is tackled and when it is not, may be qualitatively similar anyway (see, e.g., Norton et al., Reference Norton, Lindrooth and Ennett1998).

This study offers suggestions for future studies. It shows that the lifetime utility-maximization model, where foresight is assumed, is a theoretical framework that is useful for understanding linkages between pre-retirement actions and post-retirement outcomes, as people show that they are capable of factoring tomorrow's expected outcomes into today's decisions. The study also introduces future expected family and government support as important predictors of pre-retirement savings and encourages that future studies consider them in the study design.

A more practical implication of this study lies with its suggestion that pre-retirement savings should be promoted more arduously. Similar to other countries in East Asia (Aspalter, Reference Aspalter2006; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Cheng, Zarit, Fingerman, Cheng, Chi, Fung, Li and Woo2015), Thailand is an aged society with a culture of filial piety and the government whose welfare policies focus largely on strengthening the family institution. Although the family and the government have traditionally been important sources of old-age financial security, filial piety seems to have weakened over time and the government is unlikely to fully support older people (Witvorapong, Reference Witvorapong2015). This suggests that, by the time the working-age generation retires, family and government support during their retirement years may be smaller than anticipated, and, without adequate pre-retirement savings, this could lead to impoverishment. The comparison between the data used in this study, where respondents were working-age individuals, and the nationally representative Survey of Older Persons conducted in the same year (2011), where respondents were older (60 + ) individuals, reveals an interesting insight. While 96.6% and 61.0% of working-age Thais in this study expected to be self-reliant and expected themselves to be their own most important source of financial security in old age, almost half (47.1%) of older Thais under the 2011 Survey of Older Persons reported having no savings and 79.5% received monetary transfers from children (Witvorapong, Reference Witvorapong2015). Albeit contaminated by period and cohort effects, the comparison insinuates overoptimism regarding self-support on the part of the working-age population, which may affect the amount of retirement savings and their future wellbeing.

Beyond the current old-age pension system and the provision of old-age allowances, the government can further encourage retirement savings. Examples include the innovation of reliable technologies that lower transaction costs of savings and the provision of educational programs that promote financial literacy and offer financial advice. Particular attention should be given to people in the informal sector. Making up the largest portion of the population, they are financially vulnerable, without a constant stream income and the ability to form tangible savings plans.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474747220000360

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Ratchadapisek Sompoch Endowment Fund (2016), Chulalongkorn University (Grant number: CU-59-065-AS). It received an ethics exemption from Chulalongkorn University on 22 July 2019 (Reference number: COA No. 189/2562).