Introduction

Sinonasal neoplasms are a diverse group of tumours arising from the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Although sinonasal cancers account for less than 1 in 20 of head and neck malignancies,Reference Sanghvi, Khan, Patel, Yeldandi, Baredes and Eloy1 they encompass a considerable number of distinct histological entities, with almost 70 subtypes identified in the 4th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumours (benign and malignant).Reference Stelow and Bishop2

The most common malignant primary sinonasal cancer remains squamous cell carcinoma. However, a number of new diagnostic categories have been identified in the last decade. These developments have been driven by advances in immunohistochemistry and molecular analysis. Better understanding of the underlying pathogenesis and the ability to differentiate distinct subtypes has important implications for clinical practice, from diagnosis through to prognosis, and not least in the development and delivery of targeted treatment. This review aims to provide an overview of the major emerging subtypes for the ENT surgeon.

Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma

Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma is a diagnosis of exclusion reserved for highly aggressive undifferentiated carcinoma of the sinonasal tract without glandular or squamous features, but with distinct morphology.Reference Lewis, Bishop, Gillison, Westra, Yarborough, El-Naggar, Chan, Grandis, Takata and Slootweg3 It has long been thought that these may represent a group of diagnoses. Recent studies using immunohistochemistry have led to the identification of several distinct entities that were previously classified under the umbrella term ‘sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma’.Reference Agaimy and Weichert4

The SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (SWI/SNF) complex has been implicated in the pathogenesis of some of these subtypes. This complex is involved in remodelling chromatin, thus playing a role in regulating gene expression, cell proliferation and differentiation.Reference Masliah-Planchon, Bieche, Guinebretiere, Bourdeaut and Delattre5 It constitutes several core and two catalytic subunits, which are found to have tumour suppressor effects. Aggressive neoplasms arise when the respective encoding genes are mutated.

SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinoma

SMARCA4 is a catalytic subunit of the SWI/SNF complex. Loss of SMARCA4 has been implicated in a subset of malignancies of the thorax, ovaryReference Jelinic, Mueller, Olvera, Dao, Scott and Shah6 and lung.Reference Herpel, Rieker, Dienemann, Muley, Meister and Harmann7 It was very recently identified as the oncogenic driver of sinonasal cancer in two independent case studies.Reference Agaimy and Weichert4,Reference Jo, Chau, Hornick, Krane and Sholl8

SMARCB1 (INI-1) deficient sinonasal carcinoma

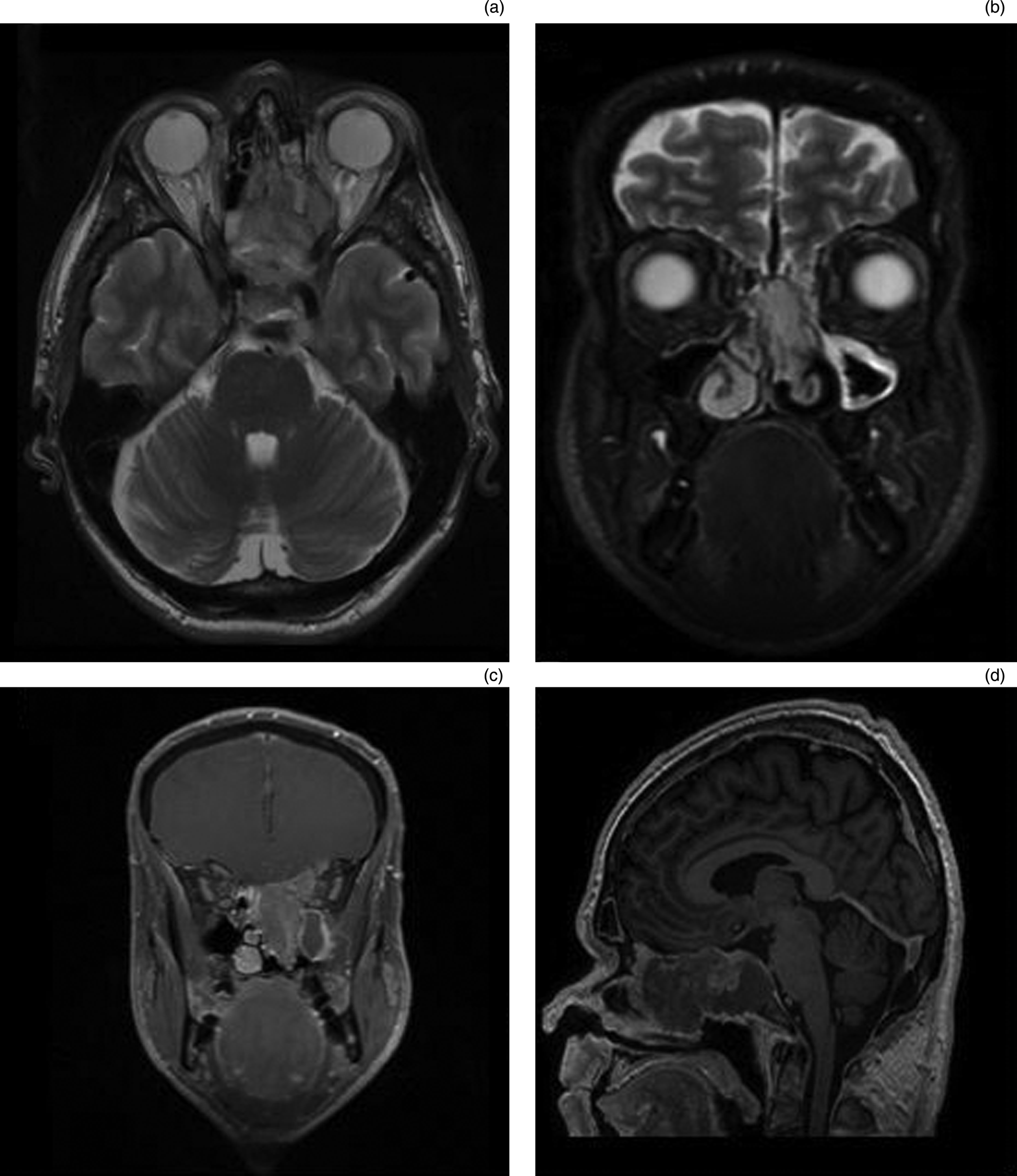

SMARCB1 is a core subunit of the SWI/SNF complex. The deletion of its gene on chromosome 22q11.2 results in aggressive sinonasal tumours that contain some rhabdoid cells. From the available case series data, these carcinomas occur exclusively in adults and tend to have a slight predilection for women.Reference Agaimy, Koch, Lell, Semrau, Dudek and Wachter9,Reference Bishop, Antonescu and Westra10 They invade locally, including into the skull base and brain (Figures 1 and 2).

Fig. 1. (a) Haematoxylin and eosin stained section from intranasal biopsy demonstrating INI-1 tumour (×200); (b) INI-1 deficient antibody – negative in tumour and positive in adjacent lymphocyte nuclei (×200); and (c) p63 antibody positive in nuclei of tumour (×200) (scale bar 500 μM).

Fig. 2. (a) Axial T2-weighted, (b) coronal T2-weighted, (c) coronal T1-weighted fat saturation and gadolinium, and (d) sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging sequences of a patient with extensive sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma centred on sphenoethmoidal region, with invasion of the left orbit, cribriform plate, planum and focal dural invasion.

NUT midline carcinoma

NUT midline carcinomas are rare cancers affecting organs along the midline of the body; the mediastinum and sinonasal tract are most frequently involved.Reference French, Kutok, Faquin, Toretsky, Antonescu and Griffin11 In the majority of cases, the pathogenesis involves a balanced translocation of the NUT (nuclear protein in testis) gene on chromosome 15q14 with the BRD4 (bromodomain-containing protein 4) gene on chromosome 19, though other various rearrangements can occur in one-third of cases.Reference French, Kutok, Faquin, Toretsky, Antonescu and Griffin11,Reference French, Miyoshi, Kubonishi, Grier, Perez-Atayde and Fletcher12 NUT midline carcinomas are characterised by early haematogenous spread; as such, prognosis is poor, with a mean survival of just nine months.Reference Haack, Johnson, Fry, Crosby, Polakiewicz and Stelow13 Aggressive treatment with chemotherapy seems to provide the optimum palliation in these tumours.

In a recent case series, only 2 per cent of primary sinonasal tumours were found to be positive for NUT. However, this rose to 15 per cent when only sinonasal undifferentiated carcinomas were considered. Therefore, it has been suggested that analysis of NUT gene translocation should be restricted to undifferentiated tumours. Immunohistochemistry has been found to be highly sensitive and specific for diagnosing NUT midline carcinoma (Figure 3).Reference Haack, Johnson, Fry, Crosby, Polakiewicz and Stelow13

Fig. 3. (a) Haematoxylin and eosin stained photomicrograph demonstrating NUT-1 tumour (×200); and (b) NUT-1 antibody positive in nuclei (×200) (scale bar 500 μM).

Human papillomavirus related multi-phenotypic carcinoma

The sinonasal tract is second only to the oropharynx as the head and neck site most commonly associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) related squamous cell carcinoma.Reference Lewis, Westra, Thompson, Barnes, Cardesa and Hunt14 Approximately one in four sinonasal carcinomas harbour a high risk HPV virus, particularly type 33.Reference Bishop, Guo, Smith, Wang, Ogawa and Pai15–Reference Bishop, Andreasen, Hang, Bullock, Chen and Franchi17 Human papillomavirus related multi-phenotypic sinonasal carcinomas (previously termed HPV-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features) overlap morphologically and immunohistologically with solid variant salivary adenoid cystic carcinomas,Reference Bishop, Guo, Smith, Wang, Ogawa and Pai15 but differ in a number of key ways (Figure 4). Firstly, the former has so far only been identified in cancers of the sinonasal tract. Secondly, over half of cases lack the MYB translocations, a genetic mutation specific to adenoid cystic carcinoma.Reference Bishop18

Fig. 4. (a) Human papillomavirus (HPV) multi-phenotypic sinonasal carcinoma haematoxylin and eosin stained section (×200); (b) p16 antibody positive in cells (nuclei and cytoplasm, ×200); and (c) HPV 16/18 high risk types that are in situ hybridisation positive (scale bar 500 μM).

In the data from the small number of cases to date, this sinonasal cancer subtype is seen in adults only, and is more common in women.Reference Bishop, Guo, Smith, Wang, Ogawa and Pai15,Reference Hwang, Ok, Lee, Lee and Park19 It appears to be less aggressive than other subtypes discussed here, with no documented cases of distant metastasis and low rates of recurrence. In a recent retrospective series, these tumours, despite exhibiting classic cribriforming and high grade features, behaved in a relatively indolent manner, highlighting the importance of histopathologically discriminating these lesions from other sinonasal tract neoplasms.Reference Bishop, Andreasen, Hang, Bullock, Chen and Franchi17

Bi-phenotypic sinonasal sarcoma

Bi-phenotypic sinonasal sarcomas,Reference Wang, Bledsoe, Graham, Asmann, Viswanatha and Lewis20 previously termed ‘low-grade sinonasal sarcomas with neural and myogenic differentiation’, are a group of low-grade spindle cell sarcomas that emerge only in the sinonasal tract, usually in the superior nasal cavity and ethmoid sinuses. Again, they are more common in women (female to male ratio = 3:1) and thus far only documented in adults.Reference Lewis, Oliveira, Nascimento, Schembri-Wismayer, Moore and Olsen21 The majority occur because of PAX3-MAML3 fusion, with a subset occurring as a result of PAX3-NCOA1 fusion.Reference Wang, Bledsoe, Graham, Asmann, Viswanatha and Lewis20,Reference Huang, Ghossein, Bishop, Zhang, Chen and Huang22 PAX3 plays an important developmental role in neuroectodermal and myogenic differentiation. The tumour can be differentiated by immunohistochemistry, as it expresses smooth muscle actin, calponin and S100.

Renal cell-like adenocarcinoma

The nomenclature of this tumour highlights its striking resemblance with clear cell renal cell carcinoma due to its copious transparent cytoplasm, as well as classical features such as prominent intra-follicular haemorrhages in some cases.Reference Zur, Brandwein, Wang, Som, Gordon and Urken23 This has the potential to pose a diagnostic difficulty given the fact that renal cell carcinoma can metastasise to the head and neck. The two can be differentiated via immunohistochemical markers such as PAX8, RCC and vimentin, which are negative in renal cell-like adenocarcinoma, alongside other compounds including calponin, actin and high molecular weight cytokeratins (Figure 5).Reference Bishop18 They appear to have a relatively favourable prognosis, with no reported cases showing recurrence or metastatic spread.Reference Zur, Brandwein, Wang, Som, Gordon and Urken23,Reference Storck, Hadi, Simpson, Ramer and Brandwein-Gensler24

Fig. 5. (a) Haematoxylin and eosin stained section demonstrating renal cell-like adenocarcinoma (×200); and (b) PAX-8 antibody negative in tumour nuclei (×200) (scale bar 500 μM).

Seromucinous hamartoma

Seromucinous hamartoma is a rare, benign lesion of the sinonasal tract composed of seromucinous ducts and glands. These lesions arise in middle-aged patients, typically in the posterior nasal cavity or nasopharynx, although they have been reported elsewhere such as the turbinate.Reference Fleming, Perez-Ordonez, Nasser, Psooy and Bullock25 The treatment of choice is complete surgical excision, with recurrence being rare.

Seromucinous hamartoma is diagnostically challenging given its similarity to other lesions. With the exception of a slight male predominance, respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma shares similar histological and clinical features with seromucinous hamartoma. This has led to the proposal that respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma and seromucinous hamartoma be considered as on a spectrum.Reference Fleming, Perez-Ordonez, Nasser, Psooy and Bullock25

The difficulty arises in distinguishing seromucinous hamartoma and low-grade non-intestinal type adenocarcinoma, particularly in view of the lack of p63 staining in most hamartomas. Immunohistochemistry is not helpful in differentiating these two entities, but pathologists can appreciate that low-grade adenocarcinoma has more complex growth patterns, including micropapillary architecture and crowded glandular proliferation.Reference Fleming, Perez-Ordonez, Nasser, Psooy and Bullock25,Reference Lee, Yoon, Lee and Lim26

Management

Sinonasal tumours are uncommon and incorporate a wide range of pathologies. This precludes large series and agreed treatment protocols. In addition, the anatomical constraints of this region, with proximity to the orbit, anterior skull base and intracranial cavity, further complicate management strategies. This highlights the need for these patients to be discussed by an expert multidisciplinary team, with input from specialists in histopathology, radiology, oncology and surgery. All patients should undergo pre-operative imaging with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, which are complimentary (Figure 2).Reference Virk, Dixon, Madani, Clarke, Gibson, Manjaly and Tatla27

Each pathology merits individual consideration. Treatment strategies are typically bi- or tri-modality. The treatment combination is dependent upon the disease staging, imaging reports, pathology findings and patient's wishes. Typically, patients will have surgery followed by post-operative (chemo)radiotherapy. Surgery can be open, endoscopic or endoscope-assisted. The choice of surgical approach is dependent upon a number of factors, including the extent of disease, availability of expertise, and imaging or intra-operative navigation.

However, for advanced tumours (i.e. those not amenable to surgical resection with negative margins) or for those with a poor prognosis, such as NUT midline carcinoma and sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma, there may be a role for induction chemotherapy.Reference Khoury, Jang, Carrau, Ready, Barak and Hachem28–Reference Ock, Keam, Kim, Han, Won and Lee31 If there is a response to induction chemotherapy, then patients proceed to radical chemoradiotherapy. Should there be progression during induction chemotherapy, then patients could be offered palliative or radical chemoradiotherapy. The role of surgery after induction chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy remains unclear. Frequently, there is no residual cancer in specimens, so less than radical surgery for prognosis, or no surgery, may become standard. It is noteworthy that chemoradiotherapy is often recommended to include the ipsilateral optic nerve to above tolerance dose, to ensure or to optimise disease control, even if this may compromise orbit function long term.

Overall, prognosis for sinonasal tract neoplasms is variable and is dependent upon pathology; five-year survival rates, for example, have been reported in the order of 50 per cent for squamous cell carcinoma, with much better rates for olfactory neuroblastoma.Reference Khoury, Jang, Carrau, Ready, Barak and Hachem28

Conclusion

Several new sinonasal neoplasm subtypes have been identified in the last decade, with a more rapid acceleration of discovery in the last few years. As demonstrated here, these are relatively uncommon cancers, but there is the potential for more frequent diagnoses should the immunomarkers discussed here be included in histological investigations. The use of molecular biology techniques is, at the present time, of great help to characterise these tumours in a more precise way.Reference Lopez-Hernandez, Vivanco, Franchi, Bloemena, Cabal and Potes32,Reference De Cecco, Serafini, Facco, Granata, Orlandi and Fallai33 Indeed, pathology appears to be the most important predictor of five-year survival.Reference van der Laan, Iepsma, Witjes, van der Laan, Plaat and Halmos34 These new diagnostic entities are well-defined in terms of their underlying aetiology, which holds promise for the development of novel therapeutic targets.

Competing interests

None declared