Gunn's aim with this substantial book (over 900 pages) is to elevate the standard of documentation within rock art research and to elucidate the regional rock art chronology of western Arnhem Land, one of the most significant rock art areas in the world. To accomplish this, Gunn used digital photographs to record the Nawarla Gabarnmang rockshelter, with Dstretch and Harris Matrix methodologies and softwares applied. Gunn also introduced Morellian analysis—a methodology that compares specific details to identify the hand of a particular artist—to Australian rock art research.

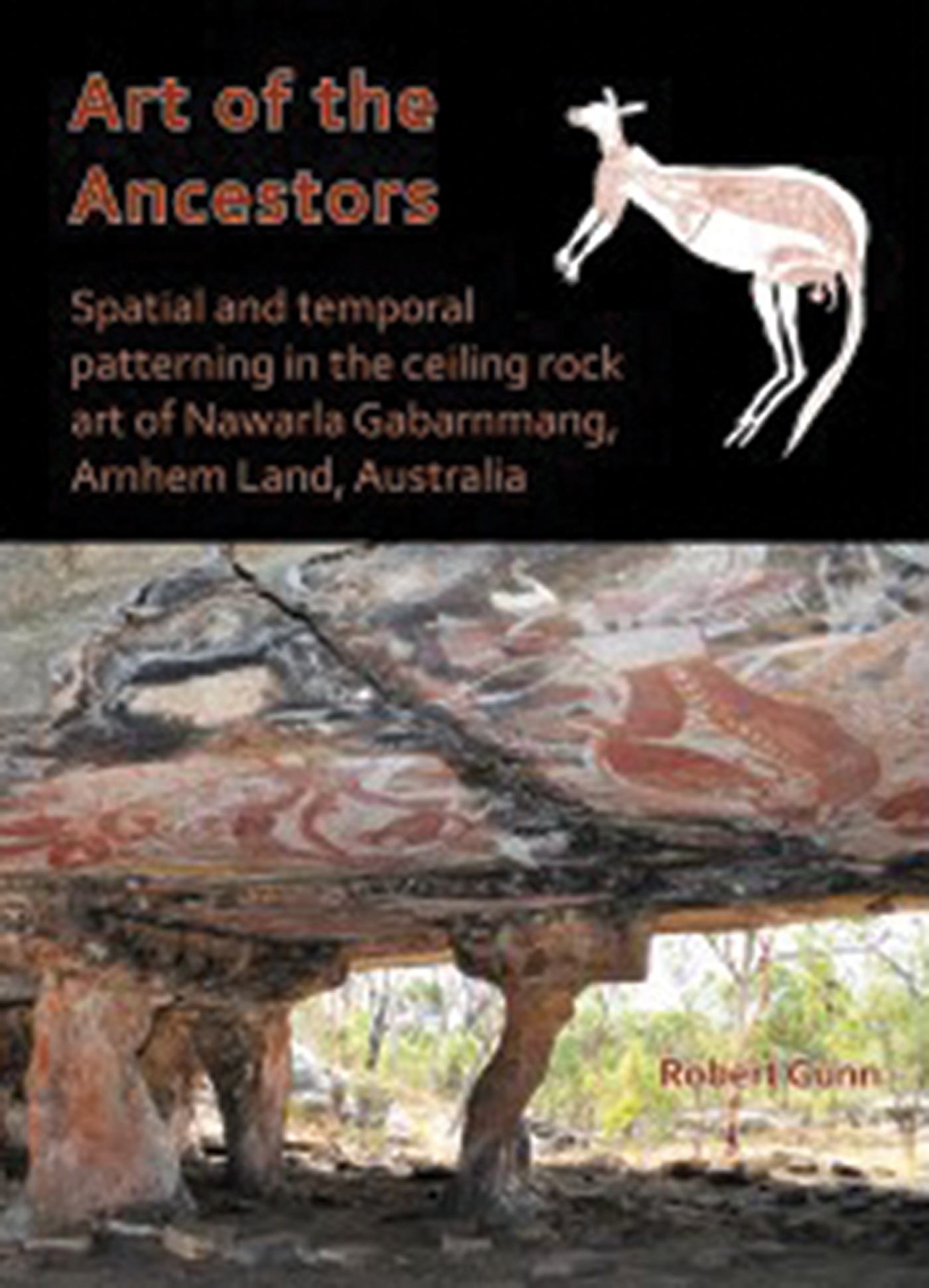

The site in question, Nawarla Gabarnmang, is perplexing. It is situated in an area referred to as ‘The Stone Country’ by Indigenous Australians, or the Arnhem Land Plateau by non-Indigenous Australians. The site was first documented in 2006 by Gunn et al. as a part of a rock art heritage project developed by the Jawoyn Association Aboriginal Corporation. The shelter where the rock art is found has been modified so that the roof appears to rest on a number of stone pillars; a pre-contact anthropogenic phenomenon rarely found or discussed within Australian archaeology. Parts of the shelter were excavated by a team of Australian and French specialists. Fieldwork started in 2010 and analyses of the recovered material is ongoing. The human occupation at the site stretches back some 50 000 years. The site has the oldest directly dated rock art in Australia, with an estimated age of c. 27 000 years cal BP. As Gunn thoroughly demonstrates, however, the surviving rock art found on the ceiling of the shelter is much younger; it is mainly dated to the Holocene with some possible earlier examples as well.

Gunn documented 1391 rock art figures on the ceiling of the Nawarla Gabarnmang shelter. These are distributed over 42 panels. The superimposition of each panel is established using first-hand observations, digital photographs and Dstretch. All 42 panels are systematically presented and analysed using a Harris Matrix program. No doubt this has been a painstaking exertion. The detailed presentation is exhaustive and solid, but also overwhelming. That said, the meticulous presentation of this assemblage is exactly what is needed in Australian rock art research. It is only through such detailed documentation and analyses of specific key sites that accurate rock art chronologies can be developed, something that has been lacking in some earlier attempts.

Gunn analyses possible cross-referencing between the superimposition sequences on each panel by comparing rock art styles, considering excavation results, direct dating using radiocarbon AMS analyses of beeswax figures and wasp nests, charting the use of colour within the different sequences, and using Morellian analysis. The rock art figures at Nawarla Gabarnmang are divided into seven artistic sequences, dating from at least the Early Holocene. Some motifs, such as the hand stencils of the three middle fingers (3MF), are placed within the latest part of the Pleistocene. Gunn's analyses show that the majority of the painted figures cannot be assigned to any one rock art style or period. These also suggest a much younger date for some acknowledged rock art styles in western Arnhem Land.

Five of Gunn's seven rock art sequences belong to the last 500 years. Frequently depicted motifs during these sequences are female anthropomorphic figures, which Gunn termed ‘Jawoyn Ladies’ because they are commonly found in Jawoyn-speaking clan countries. Gunn shows that the first appearance of this motif, and other images painted in this particular style, coincide with the first evidence for Macassan trepang fishermen visiting the coast some 150–200km north of Jawoyn Country. He argues that the Macassan interaction triggered cultural changes in Arnhem Land, which were visually mediated in the Nawarla Gabarnmang shelter; an interesting and refreshing thought, which contrasts somewhat with earlier research that has been more focused on the impact of European outsiders, several hundred years later.

The most recent artworks on many of the panels in the Nawarla Gabarnmang shelter consist of large polychrome depictions of barramundi fish in so-called X-ray style, fish which are not known in local waters. These fish are painted in a style more commonly found north of Jawoyn Country, including the plain areas of South and East Alligator River, where barramundi are common. Gunn suggests that these figures were created by visiting artists from these other areas, a highly plausible interpretation that could be further developed through historical and anthropological sources. Some of Gunn's Aboriginal informants, who visited Nawarla Gabarnmang in the 1930s, remembered these figures being present at this time, providing an important terminus ante quem for the last artworks to be created in the shelter.

Pursuit of headline-grabbing claims to the ‘oldest’ rock art has somewhat restricted discussions of how the meaning and significance of Australian rock art changed or endured. Gunn's innovative approach, focusing on the most recent art traditions at Nawarla Gabarnmang, bucks this trend and benefits from integration with the earliest historical sources and anthropological studies from the area. Gunn has tried to include as many anthropological sources as possible, but his focus remains on formal analyses of the artwork. Closer analyses of anthropological evidence might have helped contextualise the most recent artwork, not least through a deeper examination of the close relationship between Jawoyn- and Mayali-speaking clan groups to the north.

An appealing aspect of Gunn's book is that he allows his research to unfold step by step in a heuristic way, offering a very transparent read. That said, my reading was somewhat hampered by his use of the terms ‘motifs’ and ‘motif type’, which might have been more clearly defined as ‘figures’ and ‘motifs’, respectively. Nevertheless, Art of the ancestors is a vital contribution to our understanding of Australian rock art in general and rock art traditions in western Arnhem Land in particular. More painstaking analyses of the same calibre are needed before we can be assured of more accurate rock art chronologies and a clearer understanding of artistic traditions for western Arnhem Land. Those who rise to this challenge will benefit greatly from, and find inspiration in, Gunn's comprehensive volume.