Independent Work And Theoretical Reasoning

The consideration of the social and economic structure(s) of our modern societies merely as a snapshot of one moment or as a ‘blueprint’ does not acknowledge the dynamics, which are at work behind the balances expressed by the annual figures of labor market data. Stock figures may remain constant, even though there is considerable social mobility taking place in the background, mixing up the individual composition of units. The dualism of continuity and, simultaneously, change and individual regrouping already inspired Joseph A. Schumpeter to write that each social class calls to mind an omnibus or a hotel, which are always fully occupied, but concretely by continuously changing people (Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1953). We perceive an increasing relevance of biographical aspects of work, where people switch between wage or salary-dependent labor and self-employment – and vice versa – according to job opportunities, age and further individual and societal opportunity costs. Moreover, hybrid forms of employment can be found, when forms of micro entrepreneurship are combined with further activities in dependent labor. Here, we may distinguish between two competing forms of hybridity. We have either those who are self-employed and who have an additional job in dependent work, occasionally and changing or permanently the same, in order to maximize the amount of income, or – vice versa – we find those who are primarily wage or salary-dependent workers and who run some form of self-employed activity as freelancer or small(est) business owner as sideline income. Finally, we are familiar with the phenomenon that forms of self-employed activity can be reminiscent of dependent work where entrepreneurial freedom tends toward zero and incomes are sometimes also marginal.

Bögenhold and Fachinger (Reference Bögenhold and Klinglmair2016) consider four interrelated trends when observing recent self-employment patterns: (i) an increase of micro self-employment, (ii) rising figures of social destandardization and mobility, (iii) evolving blurred boundaries between self-employed and wage and salary-dependent work including diverse forms of hybridity; and (vi) clear visibility of employment patterns of precarization. The extent of social mobility is primarily a mirror of occupational dynamics and related needs of societal relations, to which Sorokin referred to early on, when he said that ‘in any society the social circulation of individuals and their social distribution is not a matter of chance, but is something which has the character of necessity, which is firmly controlled by many and various institutions by the mere virtue of their existence’ (Sorokin, Reference Sorokin1964: 207). A vast part of research on social mobility deals positively or negatively with the early conclusion by Lipset and Zetterberg that ‘the overall pattern of social mobility appears to be much the same in the industrial societies of various Western countries’ (Lipset & Zetterberg, Reference Lipset and Zetterberg1959: 12).

Looking exclusively at patterns of self-employment, we must consider convergent as well as divergent developments within individual countries and in an international comparison. On the one side, phenomena can be found indicating the risk of precariousness and poverty, and on the other side, occupational self-employment is a vehicle to bring individual people to property and wealth and which is regarded as a policy instrument for the creation of further enterprises, jobs and economic growth. The category of self-employment includes very privileged positions as well as very marginal ones, coexisting in the same category at the same time. Audretsch and Thurik (Reference Audretsch and Thurik2000) report a change from managerial capitalism to entrepreneurial capitalism. ‘Good Jobs’ and ‘Bad Jobs’ (Kalleberg, Reference Kalleberg2011) are very often opposite sides of the same coin of social and economic change in a globalized world (Beck, Reference Beck2009).

Changes in the economic geography of work have opened up whole new dimensions in the field of entrepreneurship studies internationally. Perhaps the greatest challenge to the evolving field of entrepreneurship studies is the need to generate theoretical contributions that are distinct from, and possibly even in conflict with, well-established theories in the parent fields of entrepreneurship, international business, and strategy (Di Gregorio, Reference Di Gregorio2004: 210). ‘Contextualizing entrepreneurship research does not imply abandoning received theory’, … ‘but [we must] frame phenomena and our explanations quite differently’ (Zahra, Reference Zahra2007: 451). Therefore, entrepreneurship research has to distinguish between the questions we ask and the questions we care about (Sarasvathy, Reference Sarasvathy2004).

If we employ the labor market category of self-employment as a proxy for entrepreneurship – which may occasionally be questioned, but which most closely resembles actual practice – it becomes evident that, in many countries, the majority of entrepreneurs belongs to the category of micro firms, which effectively exist as one-(wo)man-companies, with many of their number not even appearing in the yellow pages, or having their own premises, or a sign above the door. Comparing European countries in terms of the ratios of self-employment and the ratios of one-(wo)man-companies and freelancers among them, shows that the average rate of solo self-employment in Europe is >70%. In other words, >70% of all people in the category of self-employment belong to the category of micro entrepreneurs, working on their own without further employees in the economic enterprise. Distinguishing for gender, we see that, among the self-employed, female self-employed ratios are always higher than those of men.

As shown in Figure 1, the share of solo self-employment expressed as a percentage of the total number of self-employed is 71.5% in the EU-28 (data 2014). A very similar rate of solo self-employment is given in Italy (72.1%). The UK exhibits an even higher share of solo self-employment amounting to 83.0%. In Austria and Germany, the rates of solo self-employment are comparatively low; in 2014, 58.0% (Austria), respectively, 55.4% (Germany) of all self-employed individuals belonged to the category of solo self-employed. Sweden is somewhat closer to the EU-average with 61.3% of all self-employed individuals working as sole entrepreneurs without any employees. What all considered countries have in common is that the share of solo self-employment is significantly higher for females than for males. In Austria and Germany, this gender discrepancy is particularly strong (Austria: 50.5 vs. 71.4%, Germany: 50.4 vs. 65.5%). By contrast, the UK exhibits a less pronounced gender gap (81.7 vs. 85.7%).

Figure 1 Cross-country shares of solo self-employment in % of the total self-employment, 2014 (in %) Source: Eurostat-Database (2015a); own calculations.

We see two striking similarities and divergences in the international comparison. First, in all countries, the share of women exceeds that of men. Second, between countries observed in the sample, remarkable differences exist in the level of solo self-employment. For example, while solo self-employment in Germany marks 55%, at 83% solo self-employment in the UK is nearly 30% higher. The question whether one or the other figure is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ for economy and society must be answered separately and an answer relies on further indicators, such as income, stability, or reliable forms of social security (Baumol, Litan, & Schramm, Reference Baumol, Litan and Schramm2007). However, our primary concern is to find out more about the nature of self-employment.

Context Of Entrepreneurship And Fuzziness Of Categories

In order to understand remarkable differences between countries occurring at the same time, it is necessary to ask about the specific institutional settings of countries. Following this script, we have to acknowledge that the division of labor is diverse in different countries, borders between self-employment and dependent work are more rigid or fluid, degrees of informality differ, and processes of social mobility show their own rules. The (institutional) rules of the game – as Baumol (Reference Baumol1990: 894) put it – are different from country to country. Social processes between the categories of entrepreneurship and wage or salary-dependent work occur permanently in both directions, the level of statistical accurateness and informality differs, and the grey zone between entrepreneurship and dependent work is vast. Different ‘worlds of work’ (Tilly & Tilly, Reference Tilly and Tilly1994) exist and one has to analyze and to compare systematically.

Neo-classic economics attempted to arrive at theories of capitalist economies, which are not limited to specific times, regions, and their cultures, but which are universal and general so that they fit everywhere and every time. These ideas were criticized to a certain extent in different academic disciplines, since those theories seemed to deal with economies and societies in a vacuum, so that increasingly the need for a shift from observation of economies in abstracto to economies in concreto was demanded. Analyzing concrete phenomena requires an acknowledgement of the diverse institutional integrations of the phenomena. To put it in the words of Solow: ‘All narrowly economic activity is embedded in a web of social institutions, customs, beliefs, and attitudes…. Few things should be more interesting to a civilized economic theorist than the opportunity to observe the interplay between social institutions and economic behavior over time and place’ (Solow, Reference Solow1985: 328–329). Accordingly, economic historians like Polanyi (Reference Polanyi1944) or sociologists like Granovetter (Reference Granovetter1985) argued for the social embeddedness of economic institutions and social behavior.

A lesson for entrepreneurship research must be not to continue with very general wording about entrepreneurship and its resources such as finance or technology, but to link the discussion to the concrete determinants of entrepreneurship within contexts of culture, space, and time (Jack & Anderson, Reference Jack and Anderson2002; Autio, Kenney, Mustar, Siegel, & Wright, Reference Autio, Kenney, Mustar, Siegel and Wright2004; Zahra, Reference Zahra2007; Welter, Reference Welter2011). According to Welter (Reference Welter2011), one can distinguish different elements of context such as (i) institutions including society, politics, and industrial relations, (ii) business including firm sizes, industries, markets, (iii) space dimensions including countries, communities, and clusters, and (iv) family including social networks and household relations. Those dimensions play significant own roles and contribute to the structuration processes of society (Giddens, Reference Giddens1984).

The significance of the historical, temporal, institutional, spatial, and social context in understanding economic behavior is widely acknowledged in entrepreneurship research (Welter, Reference Welter2011). It is also argued that boundaries of work and traditional employment in industrial labor markets need to be redefined in order to capture the economic contribution of actors working at the boundaries between informal work, self-employment, and waged work (Blackburn, Hytti, & Welter, Reference Blackburn, Hytti and Welter2015). Critical engagement with conceptualizing micro entrepreneurship through cross-national comparisons can add to the discussion about the nature of work and production processes, and may help to fully actualize the understanding of different speeds of entrepreneurial ‘dynamism’.

The borderline between entrepreneurship and dependent labor is blurred (see Bögenhold, Heinonen, & Akola, Reference Bögenhold and Klinglmair2014) since (i) the demarcation line is not very clear and (ii) agents are always move back and forth, depending on individual job opportunities, and (iii) mixed identities or multiple jobs do mostly not exist within statistical categories (see Bögenhold & Fachinger, Reference Bögenhold and Fachinger2013,Reference Bögenhold and Fachingerb, for the case of journalists). For example, the International Labor Office standard definition has the group of employers and the group of own-account workers. The latter is defined as following: ‘Own-account workers are those workers who, working on their own account or with one or more partners, hold the type of job defined as a ‘self-employment job’ …, and have not engaged on a continuous basis any ‘employees’ … to work for them during the reference period. It should be noted that during the reference period the members of this group may have engaged ‘employees’, provided that this is on a non-continuous basis’ (International Labor Office (ILO), 1993).

Own account workers are a group of the category of self-employed workers being defined as following: ‘Self-employment jobs are those jobs where the remuneration is directly dependent upon the profits (or the potential for profits) derived from the goods and services produced (where own consumption is considered to be part of profits). The incumbents make the operational decisions affecting the enterprise, or delegate such decisions while retaining responsibility for the welfare of the enterprise. (In this context ‘enterprise’ includes one-person operations.) (ILO, 1993). In contrast to this, dependent workers are described as the following: ‘Paid employment jobs are those jobs where the incumbents hold explicit (written or oral) or implicit employment contracts, which give them a basic remuneration, which is not directly dependent upon the revenue of the unit for which they work (this unit can be a corporation, a non-profit institution, a government unit or a household). Some or all of the tools, capital equipment, information systems and/or premises used by the incumbents may be owned by others, and the incumbents may work under direct supervision of, or according to strict guidelines set by the owner(s) or persons in the owners’ employment. (Persons in “paid employment jobs” are typically remunerated by wages and salaries, but may be paid by commission from sales, by piece-rates, bonuses or in-kind payments such as food, housing or training.)’ (ILO, 1993).

According to this definition – and many others as well – actors fall under several different categorical definitions at the same time, because they are thought of in binary terms of either-or. However, dependent workers and independent actors sometimes have overlapping identities so that we call them hybrid entrepreneurs (Folta, Reference Folta2007; Folta, Delmar, & Wennberg, Reference Folta, Delmar and Wennberg.2010; Raffiee & Feng, Reference Raffiee and Feng2014). While ‘die-hard entrepreneurs’ (Burke, FitzRoy, & Nolan, Reference Burke, FitzRoy and Nolan2008) are those actors, who are portrayed in public discourse and also in economics as agents who are dynamic, willing to expand and take risks, hybrid entrepreneurs seem to be of a different nature.

Despite considerable debates regarding how entrepreneurs should be defined and depicted, it remains an elusive concept in academic literature that has an obvious semantic vagueness (Davidsson Reference Davidsson2004, chapter I). However, the ideal type depiction of entrepreneurs that permeates the mainstream entrepreneurship literature is as wholesome super heroes, innovators, and major agents of economic change, who tend to break the equilibrium through ‘creative destruction’ (Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1942). Four common characteristics of the entrepreneur reflected in entrepreneurship literature are initiative-taking, organizing and reorganizing of social and economic mechanisms, and the acceptance of risk or failure. The ultimate outcome of these activities is opportunity recognition, innovation, and venture creation, which leads to economic growth/development and human welfare (Shane and Venkataraman, Reference Shane and Venkataraman2000; Carlsson et al., 2013). However, this ideal-type representation of entrepreneurship in the mainstream literature is explicitly challenged in one small stream of literature (e.g., Williams, 2006; Williams et al., 2006). According to Williams (Reference Williams2008), the stereotypical presentation of entrepreneurs as ideal-type objects ultimately results in the marginalization of all other forms of entrepreneurship, which do not fit nicely within this positive, wholesome, and virtuous ideal-type framework.

The mainstream representation of entrepreneurship does not acknowledge the socioeconomic diversity of human actors, or their heterogeneous biographical careers and orientations (Kautonen, Down, Welter, Vainio, & Palmroos, Reference Kautonen, Down, Welter, Vainio and Palmroos2010; Bögenhold & Klinglmair, 2015Reference Bögenhold, Fink and Krausa) and their degree of happiness (Kautonen et al. 2012, Meager 2015). Consequently, informal work, which was largely believed to be mostly composed of exploitative ‘sweatshop-like’ waged employment, was either placed outside the boundaries of entrepreneurship or consigned to the margins by portraying such a type of work as not belonging to ‘mainstream’ entrepreneurship. Indeed, it is precisely because of the predominance of this ideal representation of entrepreneurs that so little attention has been paid to the relationship between entrepreneurship and the informal female home-based enterprises. However, in recent decades, especially in the context of transformation economies (Chepurenko, Reference Chepurenko2015), but also third-world countries, it has been widely recognized that many people operating in the informal economy display entrepreneurial qualities (Williams & Round, Reference Williams and Round2007; Woodwards, Rolfe, Lighthelm, & Guimaraes, Reference Woodwards, Rolfe, Lighthelm and Guimaraes2011, Williams, Reference Williams2014).

Our empirical discussion is concerned with self-employment focusing on one-(wo)man-firms as the smallest units of entrepreneurial companies where we concentrate on a pilot study in Austria. These units show considerable heterogeneity among firms and solo-self-employed actors (Kitching & Smallbone 2012, Stel & Vries, Reference Stel and Vries2015). Even when focusing just at professionals, findings in literature indicate considerable diversity (Johal, Anastasi 2015, Shevchuk, Strebkov 2015, Leighton, Reference Leighton2015) and observers and active participants do not really know the right terms to describe their activities, ranging from entrepreneurs, to self-employed, professionals, freelancers, artists, or contractors (McKeown, Reference McKeown2015). We have been trained to think in terms of reciprocal exclusion, where people belong to one or another category within the system of employment. Generally, one distinguishes between dependent work including blue- and white-collar workers on the one and independent (self-employed) workers on the other hand. Very often neglected is the fact that overlapping phenomena can be observed when people combine both categories. This is a phenomenon, which we call ‘hybrid’ entrepreneurship. Hybrid entrepreneurs are diverse in themselves; they are always in part independent self-employed people and in part wage or salary dependent actors, each one with a different story and focus on one or the other.

Empirical Study: One-Person-Enterprises Between Entrepreneurship And Hybridity

According to the Eurostat-Database (2015a, 2015b), the category of solo-entrepreneurs representing micro enterprises without further employees in their firms is about 58.0% of all self-employed people in Austria. In the EU-28, by contrast, the share of solo self-employed within total self-employment is even higher and amounts to 71.5% (data 2014). Furthermore, the Austrian statistics indicate the high relevance of one-(wo)man firms. According to the Austrian public census of company units (‘Arbeitsstättenzählung’), 329,481 firms are led only by a solo-entrepreneur, representing 52.9% of all Austrian firms (Statistik Austria, 2013, 2013a). Statistics provided by the Austrian Chamber of Commerce (‘Wirtschaftskammer Österreich’) reveal a lower absolute level of one-person enterprises with 278,411 units, which is due to the fact that a variety of types of freelancers are not included in the data. Compared with the total number of firms registered in the Chamber of Commerce, the share of one-person enterprises thus amounts to 58.1%. Since 2008, the number of one-person enterprises in Austria has risen by 35.6%. In the federal state of Carinthia there are 17,474 one-person firms listed in the register of the Chamber of Commerce. Here, the share of one-person entrepreneurs among all enterprises amounts to 56.5%. Solo-firms have their domains in the business and craft sector, as well as the information and consulting branch, where the share of one-person enterprises among all enterprises is >60 percent. Additionally, with a share of 48.1%, the trade sector has a high ratio of one-person enterprises (Wirtschaftskammer Österreich (WKO), 2014a, 2014b).

Based on the evaluated data from official statistics, it can be concluded that one-person enterprises play an especially important role in the Austrian business sector since they make up the majority of enterprises. However, there is a lack of information about their economic and social rationalities: What are their motives for being self-employed? How satisfied are the one-person enterprises with their professional situation? What does their economic and financial situation look like, and finally, can their emergence be linked to an absence of opportunities in the labor market? Primarily, our focus was concerned with a comparison of two groups: the group of hybrids as those firms where the owner has more than one activity and the group of ‘regular’ (non-hybrid) one-person-firms. Are there serious differences between the two groups and where do the differences emerge? In order to answer these questions, a comprehensive online survey was implemented in cooperation with the Chamber of Commerce in Carinthia. The survey is based on a questionnaire containing 52 questions in total. This questionnaire was developed and tested in a process lasting several months and was finally adapted for the online survey with the help of appropriate software (LimeSurvey). The contents of the questionnaire refer to the extent and motives of self-employment, client relations, success and satisfaction with self-employment, future prospects of the one-person enterprises, and socio-economic characteristics.

In 2014, a total of 9,002 one-person enterprises were contacted by the Carinthian Chamber of Commerce and were invited to participate in the online survey. The response rate was 7.0%, resulting in a sample size of 626 one-person enterprises. The generated sample is representative with respect to the legal form (over 90% individual entrepreneurs), age (mean age in the sample and in the total population: 47 years) and gender, with males being slightly overrepresented in the sample compared with the total population. The study has several findings, which are published in more detail elsewhere (Bögenhold & Klinglmair, Reference Bögenhold, Fink and Kraus2015a, Reference Bögenhold, Heinonen and Akola2015b, Reference Bögenhold and Fachinger2014; Klinglmair & Bögenhold, Reference Klinglmair and Bögenhold2014).

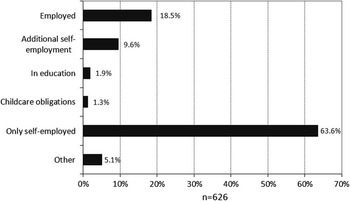

In the sample subject to investigation, slightly less than two-thirds (63.6%) of the one-person enterprises are only self-employed and perform no additional activities. In contrast, about 9.6% of the respondents exercise a second self-employed activity; a further 18.5% – this reflects 116 one-person enterprises – have an additional wage-dependent employment beside their business (see Figure 2). The latter can be described as hybrid forms of entrepreneurs because of the combination between independent and dependent employment.

Figure 2 Self-employment and additional activities (in %) Source: Own calculations.

A closer look at these hybrid forms of entrepreneurs reveals that half of them are in full-time employment (36 h/week and more) beside their entrepreneurial activity. A further 26.7% perform a secondary part-time job with an extent of 20–35 h/week. The remaining 8.6% work <20 h/week; 14.7% are marginally employed beside their activity as a one-person enterprise (see Table 1).

Table 1 Extent of the additional dependent employment

Source. Own calculations.

The high share of one-person enterprises working full-time or at least part-time beside their business activity is associated with a relative high net income from dependent employment. As can be seen from Figure 3, one-quarter of the hybrid entrepreneurs earn more than €2,000 from their additional occupation. The share of hybrid entrepreneurs receiving a net income from paid employment between €1,200 and €2,000 amounts to 37.9% in total. Hybrid one-person enterprises earning €800 or less per month from dependent employment play a minor role. The mean monthly net income from dependent employment+amounts to €1,357. From their self-employed activity, the one-person enterprises gain an average net income of €608 (see also Table 3), resulting in a total monthly net income of €1,965.

Figure 3 Monthly net income from additional dependent employment Source: Own calculations.

These results already indicate that in cases of hybrid self-employment, the one-person enterprises rarely operate as a main business. In most of the cases, the self-employed activity rather represents a sideline business, meaning that the major source of income stems from dependent employment, while the one-person enterprise portrays only a secondary income.

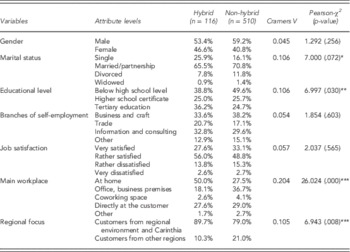

Based on the collected data it can be further shown that the hybrid self-employed differ significantly from non-hybrid ‘regular’ entrepreneursFootnote 1 with respect to selected socio-demographic characteristics, professional, as well as company-specific factors (see Table 2)Footnote 2 . First, we examined the gender distribution in the group of hybrid one-person enterprises and their non-hybrid counterparts. In the former case, the share of female self-employed amounts to 53.4%. In the comparison group of non-hybrid one-person enterprises, the proportion of women is slightly higher (59.2%). However, gender differences did not show up to be statistically significant based on a Pearson χ2 test. With regard to the marital status, by contrast, we found statistically significant differences on a 10% significance level. While 25.9% of the hybrid one-person enterprises stated to be single, the share of singles is only 16.1% in the group of ‘regular’ entrepreneurs. This result may reflect the economic necessity to gain income from more than one occupation in case of living alone, while additional incomes are not required with stable family backgrounds (Piorkowsky, Reference Piorkowsky2002; Bögenhold & Fachinger, Reference Bögenhold and Fachinger2013a).

Table 2 Differences between hybrid and non-hybrid one-person enterprises with respect to selected socio-demographic and professional aspects, Pearson χ2 tests

Note. ***,**,*Significant at 1, 5, and 10% levels, respectively.

Source. Own calculations.

Moreover, hybrid one-person enterprises appear to be significantly better educated. Hence, more than one-third (36.2%) of the hybrid self-employed have completed a tertiary education, while this applies to only 24.7% in the group of non-hybrid entrepreneurs. Conversely, the share of individuals with an educational level below high school is significantly higher in the group of non-hybrid enterprises as compared with the entrepreneurs performing both, a wage-dependent and self-employed activity (49.6 vs. 38.8%). The branch structure of the one-person enterprises is shown in Table 2. The focus here is on the business and craft sector, as well as the information and consulting branch. About one-third of the hybrid one-person enterprises perform their business activity in the business and craft branch; in the comparison group of non-hybrids this share is slightly higher and amounts to 38.2%. Another 32.8% of the hybrid self-employed are working in the information and consulting branch. A similar slightly lower proportion (29.6%) appears in group of non-hybrid one-person enterprises. The trade sector and other branches play only a minor role with shares between 12.9 and 20.7%. However, the identified differences in the branch structure between hybrid and non-hybrid one-person enterprises did not show up to be statistically significant based on the conducted Pearson χ2 test.

With respect to job satisfaction, no statistically significant differences could be found between the two groups. However, significant differences on a 1% significance level subsist with respect to the main workplace. Accordingly, hybrid one-person enterprises work intensively at home (‘home office’) compared with the one-person enterprises, performing no additional dependent professional activity (50.0% vs. 27.5%). Instead, the group of ‘regular’ entrepreneurs works especially at an own office or business premises. This result coincides with the fact that hybrid entrepreneurs mainly operate as a sideline business (in addition to a classical wage-dependent employment), making an own office or business premises unprofitable. Finally, we found out that 89.7% of the hybrid one-person enterprises operate on a regional level with most customers stemming from the direct regional environment. In case of non-hybridity, this share amounts to merely 79.0%.

Statistically significant differences between hybrid and non-hybrid ‘regular’ entrepreneurs based on a tow-sample t-test are shown in Table 3. First of all, hybrid one-person enterprises are on average significantly younger (mean age 43.6 years) than their non-hybrid counterparts (48.0 years). Moreover, in case of hybridity the one-person enterprise has existed on average for a time period of 6.9 years. In the comparison group (non-hybrid entrepreneurs) the mean duration of the enterprise amounts to 9.5 years, which is significantly higher. This result may, on the one hand, reflect the circumstance that the start-up period of an enterprise is marked by a fluent transition from dependent employment into self-employment. On the other hand, more than one income source may probably be required in order to survive economically during the initial phase of self-employment.

Table 3 Differences between hybrid and non-hybrid one-person enterprises with respect to selected socio-demographic and company-specific aspects, two-sample t-tests

Note. ***Significant at the 1% level.

Source. Own calculations.

The last three factors shown in Table 3 refer to the time exposure of self-employment and the economic performance of the one-person enterprises. As can be seen, sole entrepreneurs holding an additional dependent employment spend – as a logical consequence – significantly less time on their self-employed activity (21.3 h/week) than one-person enterprises being only self-employed (39.4 h/week). As a consequence of this result, the yearly turnover of hybrid entrepreneurs is only about one-third of the turnover that is generated by ‘regular’ one-person enterprises. Accordingly, hybrid one-person enterprises gain a net monthly income from self-employment amounting to €608 on average. By contrast, sole entrepreneurs having no additional wage-dependent employment earn on average more than twice as much per month (€1,347), compared with the group of hybrid one-person enterprises.

Conclusion: Lessons To Foster Our Understanding Of (Micro) Organizations, Institutions And Self-Employment

We have learned to recognize the central role of entrepreneurship not only in public discourse but also in academic literature. In the history of economic thought, it is the Schumpeterian–Kirznerian argumentation that entrepreneurship plays a vital role in fostering capitalist dynamics toward prosperity and wealth. Schumpeter highlighted the principally open nature of the process: ‘The essential point to grasp is that in dealing with capitalism we are dealing with an evolutionary process…. Capitalism … is by nature a form or method of economic change and not only never is but never can be stationary. And this evolutionary character of the capitalist process is not merely due to the fact that economic life goes on in a social and natural environment which changes and by its change alters the data of economic action…. This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism. It is what capitalism consists in and what every capitalist concern has got to live in’ (Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1942: 82–83). Creative destruction is a contradictory expression, which seeks to highlight the fact that competition and inherent processes toward monopolistic and oligopolistic competition are only one part of the overall economic game. Too often neglected are simultaneous processes of the creation of new firms, new ideas and even new business leaders elsewhere in an economy. Deaths and births – both of business enterprises and of individuals – are two sides of the same coin, which is economic dynamics, and Schumpeter dubbed creative destruction as an essential fact of capitalism. Innovation is the steady flow of ‘fresh blood’ through new ideas and people who keep the ‘capitalist machine’ (Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1942) going.

These ideas by Schumpeter (Reference Schumpeter1942) and Kirzner (Reference Kirzner1985, Reference Kirzner1992) have emerged as standard knowledge in entrepreneurship, theories of the firm and institutions. Summarized it sounded like this: ‘But neither a meal, nor other goods and services come about automatically. This requires entrepreneurs; people with energy and vision to initiate the production process, tap into the available resources, and find additional ones. Entrepreneurs often imagine and then implement new ways of combining the ingredients; they often try to stimulate human wants (by advertising, for example) and try out new methods of production and new products (innovation)’ (Kasper, Streit, & Boettke, Reference Kasper, Streit and Boettke2012: 3). Entrepreneurship, firms, and economic organization were increasingly thought of as elements of the same process of the (re-)constitution of the firm (Foss & Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2002) and the permanent creation of opportunities (Davidsson, Reference Davidsson2015) must be thought of accordingly at the same micro-economic level.

In contrast to this view, which is a very specific view of entrepreneurship, one may raise again the principle question of what the terms ‘entrepreneur’ and ‘entrepreneurship’ really mean (Bögenhold, Reference Bögenhold2004): For Schumpeter, Kirzner, and several followers the term was just restricted to the alert opportunity seeker who brought innovations into the business cycle, a person who is portrayed with some features of being special, dreaming of success for the reason of having success. However, the majority of independent businessmen belongs to the category of small economic actors without further employees in the firms, where the owner is his own chief and the only actor. In many countries, they have small and smallest ventures and more than half of the independent businessmen work without further employees in their companies; they just maintain self-employed activities without having a real company building, a registered company name or an entry in the yellow pages. Colloquially all these economic activities are also called entrepreneurial activities: public statistics count those people as self-employed people, who are commonly counted as entrepreneurs. Regularly, entrepreneurs are translated by self-employed actors but, then, consequently, one realizes that many self-employed people do not serve as those Schumpeterian–Kirznerian opportunity seekers in favor of societal and economic prosperity, but they are sometime very distant to those roles. They serve as the results or mirrors of economic developments rather than being those people ‘with energy and vision to initiate the production process’ (Kasper, Streit, & Boettke, Reference Kasper, Streit and Boettke2012: 3).

We increasingly find ourselves in a society that mirrors a puzzle of labor market patterns and biographical careers in which the clinical dichotomy between wage- or labor-dependent work on the one side and self-employed activities on the other side is muddied. Thinking historically, one has to study all developments within the category of self-employment within a system of permanent processes of reconfiguration of industrial relations: ‘Even self-employed people can be considered to have ‘employment relations’ with customers, suppliers, and other actors’ (Kalleberg, Reference Kalleberg2009: 12).

Consequently, also hybrid forms of combinations arise, where people have more than one job at one time, or along the biographical axis of individual careers, so that we observe patterns of multiplicity and parallelisms. Talking about entrepreneurship in the context of social and economic dynamics must deal with the subject not only in the sense of a snapshot, but also from a processual perspective, which includes entrepreneurship as instances of biographical or even episodic processes. Otherwise, one is in danger of falling into traps of ‘Illusions of entrepreneurship’ (Shane, Reference Shane2008). Research on social mobility in relation to the question about specific cohorts and patterns of transition indicates ‘multiepisodic’ processes of careers (Blossfeld, Reference Blossfeld1987). There is neither the one single lifelong occupation, nor do we find a universal pattern of setting-up on one’s own. The black and white dichotomy of being dependent or self-employed seems to have become a pattern, which loses practical relevance in many cases, because people are not either/or, but both.

Previous studies on the topic of micro entrepreneurship were mostly concerned with an investigation of available public census data, and, very often, they dealt more explicitly with the blurred boundaries between wage-dependent work and self-employment (Bögenhold & Fachinger, Reference Bögenhold and Fachinger2007; Burke, FitzRoy, & Nolan, Reference Burke, FitzRoy and Nolan2008; Folta, Delmar, & Wennberg, Reference Folta, Delmar and Wennberg.2010; Kautonen et al., Reference Kautonen, Down, Welter, Vainio and Palmroos2010). Burke, FitzRoy, and Nolan (Reference Burke, FitzRoy and Nolan2008) specified several factors determining variations of choices for entrepreneurship, including age, gender, and education. Folta, Delmar, and Wennberg (Reference Folta, Delmar and Wennberg.2010) stressed upon the hybrid nature of people in transitory phases being dependent workers and self-employed people. Sometimes they appear as being neither fish or fowl (Leighton, Reference Leighton2011). Especially, Wennberg, Folta, and Delmar (Reference Wennberg, Folta and Delmar2006) and Raffiee and Feng (Reference Raffiee and Feng2014) discuss hybrid entrepreneurship in a context of entrepreneurial processes, most firms start very small and in informal nascent stages, which are connected to hybrid forms of employment. Particularly those dynamics and transitory phases would be very valuable for studies in more detail, while other studies are just snapshots allowing a first perception of a phenomenon, which is mostly hidden when just counting figures such as numbers of firms or employment. Our study started with company units registered with the Chambre of Commerce. Had we started with public employment census data, many of the actors might have remained hidden, because many actors would have been counted as dependent employees only. Many research questions have been left open, and shall be explored through appropriate panel data.

Our study was based upon a genuine empirical survey asking about the rationality of the small entrepreneurs without further employees (including many self-employed freelancers). What are their economic and social rationalities, and how can they be interpreted in terms of recent popular discussions about entrepreneurship; is their emergence due to missing chances in the labor market for their stakeholders and/or do they reflect new interesting patterns to interpret and to realize participation in business life? All these aspects contribute to an appropriate understanding of the landscape of one-(wo)man-enterprises, while a further research inquiry delves deeper, asking about the socioeconomic logics of these small companies so that research approaches need a multidisciplinary design (Bögenhold, Fink, & Kraus, Reference Bögenhold and Klinglmair2014). The study includes companies, which are driven by need or necessity to realize any economic income at all (instead of being unemployed), and those which are also or mostly driven by ‘non-economic motives’, such as self-realization or working without hierarchies. In other words, is the existence of micro entrepreneurship due to nonexisting chances in the labor market, or does it reflect the wish to work for some extra cash in addition to regular earnings in dependent employed work? Asking about the social logic behind the pure division of companies showed that the primary focus of the empirical research is concerned with discussing the overlapping of the (formal) labor market and labor market employees on the one hand, with self-employment and entrepreneurship on the other hand. The results highlight the idea of hybridization of social, economic, and labor market categories by own empirical data and econometric analysis.

Solo self-employment as a phenomenon has always existed. Small trade and individual expertise is reported in small business studies at least since the beginnings of industrial capitalism, but the recent revival is being discussed controversially: according to the interpretation that solo self-employment is the seed for future take-offs, the findings seem to point in a different direction. Parts of micro entrepreneurship overlap with dependent work and the sterile dichotomy of dependent and self-employed work is getting muddied, because many actors have a foot on each side. Sometimes, solo entrepreneurship seems to be close to precarious work, as a result of shortcomings of labor markets and industrial relations (McKeown, Reference McKeown2005; Kalleberg, Reference Kalleberg2011). Consequently, this kind of solo self-employment may signal a lack of secure dependent jobs in the regular labor market instead of being a positive signal for upcoming winners who create a series of new jobs.

All in all, conventional perceptions of the labor force say that occupational dichotomy includes just the majority of wage or salary dependent and the minority of entrepreneurs. This notion is oversimplified and not adequate to grasp the dynamic and multidimensional system of social and economic stratification and mobility. Our study dealt with one-person-enterprises, which are the vast majority of all business owners in Europe (Burke, Reference Burke2015). Nearly 30% of our sample in Austria proved to have either more than one source of income from self-employment or they were hybrids combining income from self-employment and dependent work. It shows that these circumstances disturb the clear perception of society as based upon two major categories, it multiplies theoretical challenges.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Forschungsrat of Alpen-Adria University Klagenfurt, Austria, for providing research funds. Thanks go also to the Chamber of Commerce, Carinthia, Austria, for providing support by data access and goodwill. Two anonymous reviewers provided valuable comments which were very much appreciated by the authors.