In recent decades, credit claiming has become a prominent perspective in the understanding of the behaviour of Chinese local cadres.Footnote 1 The underlying logic here is that in a regime with a top-down accountability system, local cadres are eager to demonstrate competence to the superiors who determine their career prospects. This conceptual model helps to explain a range of phenomena. For instance, local leaders’ GDP-worship mentality has been a persistent issue since the advent of market reform, despite continued efforts to foster a balanced outlook over development. Local cadres’ credit-claiming logic is further instantiated by attempts to manipulate economic statistics.Footnote 2

Despite the power of the credit-claiming explanation, the other side of the coin, their attempts to avoid blame, has not received sufficient scholarly attention. We argue that to focus exclusively on the motivation of claiming credit is inadequate for understanding the operation of the Chinese bureaucracy and cadres’ behaviour. Two general observations bolster this view. First, undue concentration on credit claiming is based on the problematic assumption that all cadres share the same incentive structure for promotion. This is far from true. Their incentives to seek promotion are shaped by many exogenous institutional factors. For instance, since the Jiang Zemin 江泽民 era, age limits have become institutionalized to determine cadres’ qualifications for competing for higher positions. Many cadres are deemed to have reached their career ceiling before they retire; this rule of promotion renders the tournament thesis, with its underlying logic of credit claiming, inapplicable.

Second, as elaborated in the literature review, R. Kent Weaver's now well-established finding has shown the inevitability of blame avoidance within policymaking.Footnote 3 His thesis is that, owing to the greater cognitive sensitivity of constituents to negative rather than positive information (“negativity bias”), political actors have a strong incentive to avoid blame. From Weaver's point of view, policymakers must “take actions for which they can maximize credit and minimize blame.”Footnote 4 Prior research has identified various strategies used from the top levels to the frontline, either to limit career risk or to mitigate blame.Footnote 5

Some may argue that since blame-avoidance theories have developed from studies of democratic regimes, they are inapplicable to an authoritarian regime like China. However, as explained below, despite the lack of popular elections, blame avoidance remains a “political and bureaucratic imperative.”Footnote 6 We argue that an institutional source of blame-avoidance activities is inherent in the organizational structure of the Chinese state bureaucracy, whose policy directives have been typically formulated in a uniform manner intended to apply across localities. This emphasis on uniformity, as noted by Xuegang Zhou, constitutes the core of the authoritarian state, serving to reinforce central authority and the reach of state will at local levels.Footnote 7 But pursuing uniformity can generate conflict with local conditions. Exacerbating such tensions, target regimes provide an instrument to monitor and control local agents to ensure implementation of state policies within their jurisdiction. To cope with this conflict with local variations, flexibility and deviation are unavoidable and in turn could place blame on local agents if upper-level authorities stick to the original policy requirement. In this sense, the strong emphasis on uniformity in implementation constitutes an institutional source of blame risk for local agents.

Indeed, public officials’ motivations for blame avoidance have been implied by Chinese political scientists.Footnote 8 For instance, Yongshun Cai argues that the multi-level structure of the state enables the centre to reduce the uncertainty associated with repression of popular resistance, since it can assign the risky responsibility of dealing with this to local authorities.Footnote 9 In the event of negative results, the top level can maintain its image by scapegoating the lower level.

Nevertheless, compared to the literature emphasizing local officials’ incentives for claiming credit, systematic studies of their blame-avoidance behaviour are fairly limited.Footnote 10 There is a need for more solid knowledge about what types of avoidance or reduction strategies local cadres adopt. With an inductive stance, this article draws on a wide range of materials from three field studies in Guangdong province to illuminate the various strategies used by cadres to shield themselves. Compared to prior research on blame avoidance, which tends to portray street-level bureaucrats as default blame takers (who face accusations) when something goes wrong, we illustrate their role as blame makers, levelling accusations and shifting blame.Footnote 11 We focus on blame-avoidance behaviour associated with the cadre responsibility system. As a major instrument of the central authority's control over local agents,Footnote 12 an analytic focus on this system contains significant implications for state capacity building.

The article proceeds as follows. First, we outline the main arguments underlying the blame-avoidance perspective and explain its value for making sense of the behaviour of local government officials. We follow a discursive approach to the study of blame-avoidance strategies, focusing on “the discursive expressions of blame and blamelessness.”Footnote 13 Second, we present the general background of the field studies through which we collected qualitative materials to illustrate different discursive approaches to blame avoidance. We show how our analytic method uncovers the micro-politics of blame avoidance in the Chinese bureaucracy. Third, the findings section identifies the three strategies that grassroots cadres adopt to deflect blame and manage blame risk. We conclude with a discussion of the wider implications of our main findings and a number of promising future research avenues.

Theoretical Perspective: Blame Avoidance

Weaver's seminal article has stimulated a growing body of empirical studies examining how officeholders avoid blame and manage blame risk in various contexts.Footnote 14 In his monograph, Christopher Hood distinguishes between “agency,” “policy” and “presentational” strategies as three major approaches to blame avoidance.Footnote 15 Agency strategies refer to officeholders’ attempts to re-structure the architecture of government so as to shift risky responsibilities to other actors who, in turn, may become scapegoats in the case of policy failures. When using policy strategies, officeholders seek to avoid blame “by choosing policies or procedures that expose themselves to the least possible risk of blame.”Footnote 16 A typical manifestation is when local officials do everything “by the book,” or as Weaver terms it, there is a “self-limitation of discretion by policymakers.”Footnote 17 Following Markus Hinterleitner and Fritz Sagerboth's interpretation, agency and policy strategies are anticipatory forms of avoidance, deployed in advance of potential blame.Footnote 18

Hood's third strategy type, presentational strategies, concerns attempts to manipulate others’ perceptions about any associated loss and harm through various discursive devices, such as rhetoric, re-framing, justification and explanation.Footnote 19 By definition, presentational strategies particularly emphasize the discursive dimension of blame avoidance, and there has been an increasing interest in examining how this is achieved through persuasive language.Footnote 20 In contrast to agency and policy strategies, presentational strategies are reactive in that officeholders deploy this approach to mitigate culpability after blame has been raised.Footnote 21

Over the past two decades, empirical studies have demonstrated the value of this perspective for reshaping our understanding of the behaviour of government and officeholders. For instance, Michael Howlett extends the idea of blame avoidance to explain why innovation in the policy domain of climate change is limited.Footnote 22 His main argument is that the large-scale substantive response required is risky, and in order to avoid being held accountable for a policy failure, policymakers prefer procedural activities involving incremental adjustments instead of novel policy inventions. Similarly, Hood attributes the popularity of the partnership structure, an organizational arrangement infused with the rhetoric of collaborative governance, to the government's concern with blame avoidance.Footnote 23 Focusing on public service networks, Donald Moynihan applies the blame-avoidance perspective to make sense of the counterintuitive strategies used by members of the Hurricane Katrina response network, including reduced collaboration with other network actors and enhanced responsibility for tasks.Footnote 24 From a blame-avoidance perspective, both strategies enable network members to reduce political risk and protect their reputation for competence.

Blame avoidance is an inevitable aspect of the public policy process. So, to what degree has the motive of blame avoidance been incorporated into empirical studies of the behavioural patterns of Chinese local officials? We conducted a preliminary survey of the literature to approximate the major logic underlying prior research examining the behaviour of local cadres. The Social Science Citation Index was used for the literature search, to cover both area-based journals (for example, The China Quarterly, The China Journal, China Review and Journal of Contemporary China) and discipline-oriented ones (for example, American Journal of Political Science, Urban Studies and Public Administration and Development). Using ((“local cadre*” OR “local official*”) AND (China OR Chinese)) as the search term, we were able to identify 113 relevant pieces published between 2006 and 2019 (the maximum time span to which we had access). We carried out a content analysis of this body of literature and categorized items into two general groups: blame avoidance and credit claiming. We found that 84 out of the 113 primary studies reviewed (about 75 per cent) were characterized with a credit-claiming lens. Indeed, this is a conservative estimate given that studies involving both elements were placed in the blame-avoidance category. Moreover, although they touch upon the motives for blame avoidance, very few articles present a systematic study of how public officeholders use their skills and other resources to win the blame game.

Nevertheless, as opposed to noting it merely in passing, an emerging body of literature has engaged with existing blame-avoidance scholarship to examine officials’ behaviour. Ran Ran takes the lead in this respect.Footnote 25 She extends this perspective to explain the puzzle of why China retains a decentralized environmental governance system even though this is widely believed to lead to serious environmental degradation. Drawing on semi-structured interviews with local cadres and a discursive analysis of media coverage, Ran attributes the delegation of responsibility to the central government's desire to avoid the blame for poor performance in addressing pollution.Footnote 26 Xing Ni and Rui Wang introduce the conceptual framework and typology of blame avoidance to the literature on Chinese public administration and politics.Footnote 27 However, they do not address this topic in the context of the cadre responsibility system. The current study brings blame avoidance within the cadre responsibility system to the foreground by addressing local cadres’ avoidance strategies directly.

With respect to our research setting, two major characteristics of the Chinese cadre responsibility system lead us to expect that blame avoidance plays a significant role in the bureaucracy's everyday politics. First, the complex vertical and horizontal relations between and within the central and local governments imply that local authorities are frequently faced with conflicting demands from different superiors, so that “government behaviour is seen as inappropriate in one policy area but may be reasonable and legitimate in view of another policy or regulation.”Footnote 28 Therefore, claiming credit in both domains becomes an impossible mission, a policy dilemma that renders blame avoidance indispensable for survival under these complex accountability regimes.

Another characteristic of the cadre responsibility system concerns its strong emphasis on sanctions. To pressure local officials to take accountability demands seriously, the cadre responsibility is typically accompanied by an elaborate sanction and reward structure.Footnote 29 Furthermore, to facilitate interjurisdictional competition and higher achievement, performance is typically measured in relative terms (as indicated by the reliance on rankings). Apart from the few at the top of the league tables, most are seen as “laggards” or “losers.”

As such, the cadre responsibility system creates blame-generating conditions for local cadres. According to Mark Bovens, being accountable “means being responsible, which, in turn, means having to bear the blame.”Footnote 30 As a corollary, avoiding blame would constitute a major concern for those accountable. So, an important question is, how do local officials avoid blame, and manage blame risk, under accountability pressures? Compared to previous studies that prioritize the blame avoidance of those in top leadership positions, this study focuses on street-level bureaucrats who deal more or less directly with the public and who are responsible for service delivery. In the blame world, the people at the bottom of the administrative pyramid become blame takers and this is particularly the case in China: grassroots cadres turn out to be “default” blame takers when they fail to meet targets set by their superiors or after policy fiascos. However, prior research has paid insufficient attention to their complementary role as blame makers. Examining them as blame makers can deliver a fuller understanding of the blame game, and illuminate the challenge to state capacity building through the cadre responsibility system.Footnote 31

In summary, we draw on blame politics theory, which has been contributed to by scholars such as Weaver and Hood, and extend this perspective to an authoritarian regime such as China. By doing so, we are able to reorient the study of Chinese local officials’ behaviour from a credit-claiming to a blame-avoidance perspective. Moreover, compared to the dominant official discourse and an emerging line of scholarly work on blame avoidance in the Chinese context in which street-level bureaucrats have typically been viewed as the blame takers in the blame world, we illuminate the role they place in creating blame, redirecting blame and levelling accusations. Below, we explain in detail how qualitative data from our field studies illustrate how local cadres act as blame makers in this context.

Research Method

Research background

In view of the importance of blame avoidance, we seek here to illuminate this subtle and hidden aspect of the Chinese bureaucracy through our three field studies in Guangdong. Although these projects were not explicitly designed for the objective of this article, each case was purposively selected for its rich information on local cadres’ responses to accountability pressures and allows us to observe how blame avoidance, as a sensitive phenomenon, occurs naturally in real contexts. As seen below, the qualitative data collected in the first two are mainly used to illustrate reactive blame avoidance, while the third field study provides a unique opportunity to examine the anticipatory type. We present contextual details for each field study below.

Field study #1

The first study was based on fieldwork for the first author's doctoral thesis (May to June 2013). In-depth interviews with local cadres in five cities were conducted to understand the daily operation of the cadre responsibility system in different policy domains. Interviewees were selected from policing, environmental regulation, economic development and farmland conservation; these are policy sectors in which performance has been increasingly measured in quantitative terms. Although interviewees were not directly asked how they avoided blame, their reactions to their departmental cadre responsibility system clearly indicated attempts to do so.

There were 24 interviews (of 40 local cadres), lasting from 30 minutes to three hours. Interviewees were asked for an in-depth account of the target system set by the upper-level government, any difficulties in attaining those targets, and their ideas on how to improve the evaluation system. Some interviews were not audio recorded, so post-interview memos were relied upon to record the main themes emerging. To supplement the qualitative interviews, the first author collected documents on the cadre responsibility system. Equally important were the documents reviewing the results of performance evaluations, which made it possible to reveal without direct interrogation how local cadres responded to these appraisals.

Field study #2

The second field study (March to September 2016) was based on a project commissioned by the local government in Z City, Guangdong province. The materials collected were used to examine local cadres’ responses when blamed for underperformance (reactive blame avoidance). The municipal police department's main objective was to formulate policy proposals to improve social safety in G District, close to Macau. From November 2014 onwards, the police developed a quantitative measurement called the safety index (ping'an zhishu 平安指数) to measure the safety of local communities and to hold sub-district leaders accountable.

The rankings of the Z City safety index indicated that G District was an “unsafe” area. In August 2016, as a major part of this commission, we organized focus groups from G District departments with functions and responsibilities related to the safety index (for example, crime reduction) for their views on improving index score in the area. These were audio recorded and fully transcribed. It turned out that the participants disagreed about how far the scores reflected the district's degree of security.

In addition to the focus group data, we were granted access to documents submitted by the departments responsible for the safety index. These texts contained their own accounts of what led to poor index performance, which enabled us to examine their blame-avoidance efforts in a real context.

Field study #3

We drew on a further government-commissioned project to explore how grassroots cadres seek to manage blame risk in the aftermath of a blame firestorm (i.e. anticipative blame avoidance). Under growing accountability pressures, deaths from work-related accidents have become priority targets with veto power.Footnote 32 The background was a serious landslide of construction waste in S City, Guangdong. The State Council investigative team attributed the accident to human negligence and mismanagement, with more than 70 officials either prosecuted or subjected to Party/administrative discipline. This blame storm triggered a strong sense of scapegoating among the grassroots cadres enforcing regulations and supervising work safety.

To boost the morale of local officials, our team (coordinated by the second author) was commissioned to develop a policy framework (March 2016 to March 2017) specifying under what conditions misconduct and negligence could be tolerated (for example, when actions were unintentional). The data used in this article came from two major sources. First, a total of 15 departments, largely those charged with causing the landslide, were required to provide concrete recommendations as to when administrative negligence might be forgiven (rongcuo 容错). As seen in the findings section, these textual materials were valuable for a systematic analysis of grassroots cadres’ anticipatory forms of blame avoidance. Second, after formulating a provisional framework, we organized focus groups from five departments blamed for failing to prevent the accident. Our major purpose was to solicit their suggestions for enhancing this framework. As shown below, grassroots cadres from those departments took this chance to shift the responsibilities with blame risk away from themselves.

Data analysis

We have tried hard to choose an analytic approach that fits our research question. In accordance with a discursive approach to blame avoidance that treats language as the “micro-level building blocks of blame game,”Footnote 33 discourse analysis was used to uncover the discursive strategies used by local cadres for avoiding blame and managing blame risk.Footnote 34 Our interpretation of discursive strategies is consistent with the approach used by Sten Hansson, who views discursive strategies of blame avoidance as “macro-conversational practices” deployed by officeholders to minimize blame (risk).Footnote 35

This methodological decision is based on the growing recognition that the blame game is essentially a language game in which blame takers make use of linguistic resources to affect an audience's perceptions of their blameworthiness.Footnote 36 The discursive dimension of blame avoidance can be easily seen in presentational strategies.Footnote 37 Even though policy and agency strategies are aimed at organizational structures and procedures, both must be articulated through persuasive language, and in this sense, discourse analysis provides a valuable approach for revealing officeholders’ attempts at blame avoidance.

The three field studies generated interview transcripts, official documents and research memos. Given the large amount of textual material involved, NVivo 11.0 was used to store, code, organize and retrieve the data. We followed an inductive approach to data analysis, a process involving both open coding and conceptual coding.Footnote 38 Open coding was used to break down the data into segments and to bracket blame-avoidance attempts in concrete settings. During the process, we paid attention to the narratives, metaphors and ironies that emerged in grassroots cadres’ descriptions of target regimes, and the emotions expressed in the interviews, which hinted at their reactions to the blame incurred. The second round of coding developed higher-level concepts for grouping the descriptive segments of the blame-avoidance attempts identified. The strategies were divided into three categories: de-legitimating performance standards, re-attributing blame and transferring blame risk. In the next section, we examine how each discursive strategy plays out in grassroots cadres’ responses to the implementation of the cadre responsibility system.

Research Findings

De-legitimating performance standards

To ensure the implementation of a policy objective in diverse situations, performance standards are intended to be abstract and devoid of context so that they appear applicable to every locality. Nevertheless, using a consistent standard applicable across localities implies the suppression of individuality and contextual detail. As a consequence, this emphasis on standardization and uniformity is likely to introduce a conflict with particular local circumstances.Footnote 39 Our primary data suggest that local cadres stressed this internal tension embedded in the assumptions of the cadre responsibility system. A major blame-avoidance strategy was to question the appropriateness of performance standards in two respects: do the performance criteria fit the local conditions? Are the performance targets set by the criteria attainable?

Do the performance criteria fit the local conditions?

We use farmland conservation as an example. In response to intensifying pressure from the central government to curb the loss of arable land, a composite measurement tool of three indicators was developed by the Guangdong provincial government to compel municipal governments to protect farmland. The first of these gauged agricultural acreage within a city's administrative jurisdiction, the second measured the annual growth in agricultural acreage, and the third evaluated the city's contribution to the increment in the agricultural acreage in the province. This index sent a clear signal to local authorities: it was crucial to protect existing farmland and also to increase acreage. Nevertheless, bureaucrats from the department for farmland protection in one Pearl River Delta city explicated the tension between the target regime and local circumstances (this city won no provincial award for farmland conservation): “Each city has its own strengths; it has different positions, different bases, different orientations, and different directions of development. Should it be mandatory for land to be tilled just to meet the evaluation criteria? Should it be mandatory for the Pearl River Delta to be tilled?”Footnote 40 This interviewee clearly held that the goals in the performance criteria did not accommodate the city's economic growth priorities. He ridiculed the absurdity of the performance metrics by suggesting the Delta, the engine of the province's economy, would have to shift its policy emphasis from industrial to agricultural development to meet one performance target.

In reports from the same department which explained why the city lagged behind others in terms of quantitative indicators measuring farmland protection, the reason given was that the city's unique geographic position and strategic emphasis contributed to the evaluation outcome. One argument frequently invoked was that Z City was not comparable to cities with an orientation towards agricultural development. In the department's own words, Z City has inadequate natural endowments (xiantian buzu 先天不足). By highlighting the city's unique circumstances, they implied that the performance criteria ignored local contexts, so it was unfair to blame the department for the outcome of the evaluation.

Our experience from the second field study confirms officials’ discursive agency in exploiting the paradox between universality and individuality to deflect blame. A policy document explained why their district, as measured by the safety index, fell short of others’ performance:

For one thing, the safety index is calculated based on actual population (shiyou renkou 实有人口). The actual size of the population in the area administered by the police station is 62,000, but the size of the migrant population is around 500,000. The calculation of the safety index does not take into account the influence of the migrant population, which has led to the poor performance of this district on the index.Footnote 41

In other words, the index unfairly failed to take into account the floating population. In G District, the head of the office complained in a focus group that the safety index put them in an unfavourable position compared with other districts: “using the same performance standards, we are bound to be at a disadvantage.”Footnote 42 The sub-district office managed to persuade upper-level authorities to adjust the calculation of the index to take their circumstances into account, which directly resulted in a substantial improvement of the score.

Are the targets attainable?

Framing goals as unattainable is another method of contesting the legitimacy of performance targets. When performance criteria are devised, they are typically assigned one of two major types of targets. Some indicators have clear thresholds for success or failure; others are not assigned any specific targets: performance is determined on the basis of lateral comparisons. Compared to the first category, the “league table” approach is intended to incentivize officials to achieve better policy outcomes. Nevertheless, those evaluated on a relative basis managed to contest that design by framing the targets as unachievable. A conversation between two police officers illustrated their dissatisfaction with lateral comparisons (the department attained all the indicators but did not obtain a favourable position in the provincial rankings):

Interviewee #1: It's my interpretation that, if you set me a target, and I achieve it, then, I'm sorry, but I should have the [full] score. If each local police station achieves the target, then it implies that the sub-bureau has completed its job; if each sub-bureau has done its job, then it implies that the municipal bureau had done its job. You cannot judge performance according to a ranking and punish those who are ranked below others.

Interviewee #2: A bottomless pit. The problem is whether or not you can reach the peach if you jump. Now, [the target set by] the provincial department is impossible to reach, no matter how hard you jump.Footnote 43

From these interviewees’ points of view, performance should be assessed in absolute instead of relative terms, which means that any local police station should be regarded as fulfilling its target, even though it might rank at the bottom relative to others. They likened the use of lateral comparisons to “bottoming out” in business, and aiming for a good position was like a “bottomless pit” (wudidong 无底洞); evaluating their performance through benchmarking was the equivalent of assigning unlimited targets. Note that the interviewees used “we” and “I” to refer to themselves, and “you” to refer to whoever assigned them various targets, a linguistic practice that further distanced them from the target regimes. This strategy of “linguistic membership categorization,” following Hansson, was frequently used, conveying their dis-identification with the cadre responsibility system.Footnote 44

To “demonstrate” that the performance criteria and the goals were unrealistic, local officials shared many stories of how their colleagues played games with target regimes set by the upper-level government. For instance, under the pressure of evaluation, police officers broke down a single case into multiple cases, deliberately lowered standards for detention,Footnote 45 and even faked crime data to make their performance appear better.Footnote 46 In these narratives, local officials presented themselves as the victims of these performance regimes, forced to use “dirty” means to achieve their targets. From their perspective, performance regimes were like “immoral laws” and they should be exonerated for not attaining the goals they were set.

Re-attributing blame

A precondition for blame assignment is to identify the carrier unequivocally. But ambiguity is an inevitable component of social reality and organizational life.Footnote 47 Ambiguity in performance evaluations mainly derives from the complexity involved in disentangling the impact that different actors have on policy outcomes. It is a formidable task to establish an unambiguous causal linkage between a policy outcome and a specific government body, and so in turn causal ambiguity becomes a rhetorical resource that enables local officials to re-attribute the reason behind policy failures.

In the third field study, officials from departments subjected to blame sought to mitigate blameworthiness by drawing attention to inadequate resources and staff shortages as the main reasons for their inability to prevent the tragedy. For instance, an interviewee from a sub-district office responsible for the supervision of work safety complained that the office had to perform heavy tasks with limited personnel: “Our department's staffing quota is four [authorized size of a government body], and we only have two people in place. We are deceiving ourselves if we say that we do a good job. That is the truth. We can't do anything about it. Even though we patrol every day, they [the targets] are not within our reach.”Footnote 48

Similarly, another interviewee from a division of the bureau of urban development stressed the lack of expertise in the handling of professional tasks delegated to their department: “For the process of inspections for technical issues, we do not have a professional force. We can only take a look at the completeness [of procedures]. Using landslide accidents as an example, many of us said that even an academician could not predict the incidence of a landslide.”Footnote 49

A local official from a sub-district office likened the mismatch between the tasks assigned to grassroots levels and the resources allocated to that of a pony pulling a heavy truck (xiaoma la dache 小马拉大车). From the official's point of view, the lack of personnel prevented the office from implementing regulations as stipulated by the law.Footnote 50

Police officers also sought to re-attribute blame by exploiting the causal ambiguity embedded in the cadre responsibility system. Influenced by neo-liberal thinking, the effectiveness of police performance has been increasingly measured through two major metrics: objective crime reports and citizens’ ratings.Footnote 51 An implicit assumption is that the more effective a police force is in fighting crime, the lower the number of crime reports and the higher the level of citizens’ satisfaction with the police will be. This assumed logic is manifested in how performance evaluation systems are designed, with the number of crime reports (jingqing 警情) and citizens’ ratings of police performance/community safety being major measurements of performance. Nevertheless, those subjected to these measurements still developed alternative explanations for any failings based on the two major sets of indicators by exploiting the causal ambiguity.

In a report evaluating the general safety conditions of Z City, the municipal police explained why the survey results were lower than expected:

Z City is an immigrant city. The quality (suzhi 素质) of the population is relatively high, and social safety is relatively good; therefore, citizens’ expectations [of better service] are relatively high. In other words, the people have a relatively lower level of tolerance for [a lack of] public security, and they place relatively high demands on their public security bureau.Footnote 52

In other words, since immigrants tend to have high expectations of public services and, therefore, provide lower evaluations of police effectiveness, unfavourable ratings were only to be expected. By highlighting the city's demographics and the cognitive bias in citizens’ evaluations, it became possible to contest whether these subjective metrics truly reflected police performance, and this, in turn, made it difficult to blame the police officers for their low index score.

The number of crimes reported was another indicator given important weight in the police performance management system, and this was largely measured through the number of calls made to police stations.Footnote 53 The statistics for crime reports were then aggregated to measure performance at higher administrative levels (i.e. sub-districts, districts and cities). Compared with measurement through citizens’ perceptions, this indicator is less vulnerable to cognitive bias, and therefore more objective. As a result, the level of reported crime had been increasingly adopted as a key indicator of social safety and police effectiveness. But once again the inherent causal ambiguity allowed those being appraised to re-attribute blame when their scores were below target. An officer responsible for performance evaluations explained his understanding of the fluctuation in reported crime as follows:

We should say the jingqing [the number of crime reports] in a community, the variability within a period, is not really determined by the intentions of local police stations. They may make tremendous efforts, but the jingqing is up; they may not work very hard, but the jingqing declines. In the Spring Festival, for example, many immigrants leave, and the majority of those who stay are natives, and it is likely the incidence of criminal cases is not very serious.

So, by presenting the fluctuation in the reporting of crimes as being independent of police efforts, the informant is questioning the validity of this indicator. If we accept the interpretation, it is unjustifiable to blame local police officers for their performance on this measurement. Indeed, by attributing the crime levels to external forces, local cadres invoked a “fatalist” narrative, portraying “many problems and failures in societal life [as] unique, random, unpredictable, unintended, and involve[ing] indeterminate ‘X-factors’.”Footnote 54

Transferring blame risk

De-legitimating performance standards and re-attributing blame are essentially presentational strategies used by blame takers to develop persuasive arguments for shifting the blame away from themselves. Both strategies are reactive in the sense that they are mainly adopted after the individuals have already been blamed for failing to meet performance targets. However, prior research has shown that blame avoidance can be anticipatory when officeholders take action in advance to minimize blame risk. According to Hood, agency strategies are a useful approach for reducing exposure in blame storms.Footnote 55 To be specific, agency strategies involve attempts to “craft organograms that maximize the opportunities for blame-shifting, buck-passing, and risk transfer to others who can be placed in the front line of blame when things go wrong or unpopular actions are to be carried out.”Footnote 56 By redirecting blameworthy responsibilities away from themselves, policymakers attempt to conceal the need to engage in the blame game when something goes wrong. Weaver regards this approach as the “best way for policymakers to keep a blame-generating issue from hurting them politically.”Footnote 57

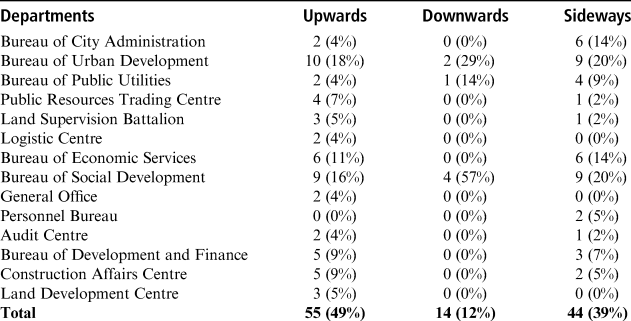

Our analysis of the data from the third field study suggests that local officials’ responses to accountability demands illustrate a clear logic of responsibility avoidance, as they attempted to transfer blameworthy tasks to other actors in the accountability system. As mentioned above, this field study was precipitated by the construction waste landslide in S City. Although the State Council attributed this accident to human negligence and mismanagement, local officials from censured departments blamed structural problems within the accountability system. The blame storm triggered a strong sense of grievance and fear among the cadres responsible for enforcing regulations and supervising work safety. This negative mood translated into an attempt to shift responsibilities with blame risk onto other actors. Our analysis of the documents from 15 departments revealed 275 suggestions. Among them, 113 pieces of advice involved attempts to pass potentially blameworthy operational tasks to others in the accountability system. We divided these into three general directional categories, which we explain below (see Table 1 for distribution of strategies across departments).

Table 1: Matrix Coding of Blame-avoidance Strategies and Departments

Upwards

Transferring responsibility upwards is when officials attempt to assign responsibility to those in charge of making decisions (49 per cent of the suggestions). In the focus groups during the third field study, grassroots cadres commonly complained of being made into scapegoats by city-level leaders. They felt it was unfair to blame local cadres for simply implementing directives issued by superiors. Nearly all departments (14 out of 15) adopted this strategy to transfer blame risk. For instance, the bureau of social development suggested that, “For those errors and faults that occur during law enforcement as required by the head of the bureau, the executors should not be held accountable.”Footnote 58 Similarly, the land development centre requested exemption from blame for violating relevant regulations or procedures, or for reducing the timeframe when implementing construction tasks assigned to it. A shared feature was that grassroots cadres emphasized their role as executors of administrative fiats, indicating that when anything went wrong, those who had made the decisions should take the responsibility. As observed by Hood, in the blame-avoidance world of front-line staff, a major card to play is to “claim victimhood” so that the blame can be shifted back to players further up the line.Footnote 59 In this sense, front-line troops become blame makers.

Downwards

Transferring responsibility downwards reflects local officials’ attempt to delegate responsibility to subordinate bodies.Footnote 60 This category accounted for 12 per cent of all advice. Public agencies attempted to transfer part of their responsibility to sub-district offices in the name of jurisdictional management (shudi guanli 属地管理), since the sub-district offices are the executive agencies of district government. For instance, as the number of petitions associated with urban renewal continued to increase, the bureau of urban development, which is responsible for urban renewal programmes, proposed to “stipulate directly that the sub-district office is the leading unit responsible for handling petitions related to urban renewal.” For departments with subordinate branches, delegation was a rational strategy to redirect risky tasks to front-line staff. However, aware of the blame risk of delegated responsibilities, local cadres from sub-district offices expressed their objections during the focus groups to the principle of jurisdictional management and stressed that they were not prepared to have work delegated to them as they lacked personnel. In the words of one sub-district office interviewee, “[superiors] retain the power of approval, but throw down the task of enforcement to us, and give it the fine-sounding name of delegation.”Footnote 61

Sideways

Allocating responsibility sideways refers to attempts to move responsibility onto others at the same administrative level. The document analysis confirms that public agencies tried to pass duties that might attract blame to other policy agencies (11 out of the 15 departments employed this strategy, and 39 per cent of the advice belongs to this category). For example, the bureau of economic services sought to transfer the responsibility for regulating land use, a law enforcement duty that typically involved civil conflicts, to the land supervision battalion:

Our bureau is not equipped with the law enforcement capability to assume responsibility for monitoring illegal land use. According to relevant regulations, the land supervision centre is responsible for the daily supervision of state-owned agricultural land and basic farmland. Therefore, the land supervision battalion should take responsibility for detecting illegal activities occurring in [the use of] agricultural land [including basic farmland].Footnote 62

Conclusion and Discussion

Drawing on qualitative materials collected in three field studies, this article demonstrates that blame avoidance constitutes a discernible logic underlying local officials’ reactions to the implementation of the cadre responsibility system. Specifically, we identify three discursive devices employed by cadres to avoid being blamed: de-legitimating performance standards, re-attributing blame and transferring blame risk. In de-legitimating performance standards, local cadres exploited the tension between the universality and individuality inherent within the cadre responsibility system to elaborate on and contest whether performance criteria fitted localities, and whether performance targets were attainable. In re-attributing blame, they attempted to exploit the causal ambiguity inherent in accountability systems to give an alternative account for unsatisfactory performance. Indeed, the main logic shared by both strategies is to portray those being evaluated as the “victims” of badly designed target regimes.Footnote 63 In transferring blame risk, a third approach to blame avoidance, local cadres attempted to shift unpopular duties both horizontally and vertically to other actors in the accountability system.

Our findings have three wider implications. First, we show that blame avoidance constitutes an important and inevitable aspect of the operation of the Chinese bureaucracy. As argued at the outset of this article, prior research examining cadres’ behaviour has been dominated by the credit-claiming explanation, emphasizing the incentive to attain performance targets imposed from above in order to excel in tournament-like competition. However, as we have shown, avoiding blame is another major concern and takes both anticipatory and reactive forms. Moreover, in contrast to dominant official discourse as well as an emerging body of research on blame avoidance in the Chinese context that tends to view grassroots cadres as blame takers, we demonstrate the ways in which cadres become blame makers.

This paper makes a theoretical contribution to the literature on blame-politics theory by conceptualizing blame games as language games, a novel perspective that directs attention to the linguistic components of blame games. Mainstream approaches to blame-avoidance strategies have implied the role of language in blame-avoiding behaviour,Footnote 64 but as noted by researchers from the field of blame politics, scholarship has yet to bring the discursive features of blame-avoidance behaviour to the forefront of empirical studies.Footnote 65 Our study echoes the recent call to devote more attention to the linguistic aspects of blame games by focusing on political actors’ skilled use of language in mitigating their blameworthiness.Footnote 66 Examining blame games as language games, we employ a discursive analysis in this article to analyse how officeholders develop persuasive arguments to deflect blame and manage blame risk. Drawing on materials collected during fieldwork, we identify three major discursive strategies used by street-level bureaucrats in mitigating/avoiding blame.

Second, our research illustrates the limits of using the cadre responsibility system as an incentive mechanism. For years, holding public officials accountable for their performance has been considered “a Good Thing, of which it seems we cannot have enough.”Footnote 67 Faith in quantitative performance indicators to achieve state will has resulted in applying the cadre responsibility system widely across policy areas. Many scholars of Chinese politics point to the cadre responsibility system's viability in building up state capacity.Footnote 68 Similarly, Suisheng Zhao identifies making local cadres “more accountable for their bad performance” as an important component of the “China model.”Footnote 69

Although holding cadres accountable for performance metrics may pressure them to prioritize corresponding policy domains, the cadre responsibility system generates the opposite effect; those evaluated have a strong tendency to avoid responsibilities with high blame risk and to attribute poor performance to external factors. In this sense, blame-avoidance behaviour may actually limit the power of the cadre responsibility system to strengthen the state's capacity.

Third, our research has implications regarding the repeated observation of attempts to game the performance evaluation process. A large body of public administration literature shows that introducing quantitative performance indicators triggers various types of strategic responses;Footnote 70 those evaluated may “manipulate the ranking data without addressing the underlying condition that is the target of measurement.”Footnote 71 Such a dysfunction has been widely noted in empirical studies of the implementation of the cadre responsibility system in China.Footnote 72

Although an examination of the underlying explanations for performance gaming is outside the scope of this article, the empirical findings provide some clues regarding the observed strategic responses. Local officials’ perceptions of accountability could be one important driver: “if accountability is perceived as illegitimate … any beneficial effects of accountability should fail and may even backfire.”Footnote 73 Following this logic, local officials’ lack of identification with the accountability system, as mirrored in their responses to the target regimes, constitutes a plausible explanation. In a sense, widespread gaming behaviour is a natural product of dis-identification with the target regimes.

This article has uncovered local cadres’ strategies to avoid blame and manage blame risk when responsibility systems are implemented. However, important questions remain for future research. First, a linguistic perspective directs our attention to identifying the discursive strategies involved in warding off blame. It makes sense to employ an experimental design to examine the effectiveness of these strategies and how such effects are moderated by situational factors (for example, the audience).

Second, following Hood's suggestion, one must distinguish between positive and negative forms of blame avoidance: the difference lies in whether it is “sharpening or blunting policy debate, pinpointing or diffusing accountability, and increasing or reducing transparency.”Footnote 74 Nevertheless, existing research tends to see such behaviour as only negative, as the antithesis of good governance and accountability. But blame avoidance can produce positive effects in some circumstances. For instance, some blame-avoidance attempts by local cadres speak to the rigidity of performance criteria and call for adjustments. It therefore makes sense to take a more balanced view of their activities, which may invite deeper reflection about some dysfunctional features of the system.

Third, future research should explore other approaches to blame avoidance in the Chinese bureaucracy. Prior research notes the impact of anticipatory blame-avoidance behaviour, mainly involving policy and agency strategies, on institutional infrastructure and on the procedures that organizations follow. Nevertheless, anticipatory blame-avoidance strategies are less visible and more difficult to study than reactive strategies.Footnote 75 We present some evidence of the anticipatory form in the third field study. Future research may follow an ethnographic approach, involving long-term participant observation, to investigate how both the architecture of local government and its procedures are structured so as to minimize blame risk.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor Tim Pringle and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. Jiayuan Li acknowledges financial support from the National Social Science Fund of China (Project No. 16CGL053, Project No. 18ZDA108). Xing Ni acknowledges financial support from the National Social Science Fund of China (Project No. 20ZDA105).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical notes

Jiayuan LI is associate professor in the School of Public Administration, South China University of Technology. His current research interests revolve around the cadre responsibility system and the behaviour of Chinese local government.

Xing NI is professor in the School of Politics and Public Administration, South China Normal University. His main research interests include public organization theories, human resource management, performance management, and corruption and anti-corruption in China.

Rui WANG is a research fellow in the School of Management, Lanzhou University. Her research focuses on cadre management, public accountability and crisis management.