The birth of an icon

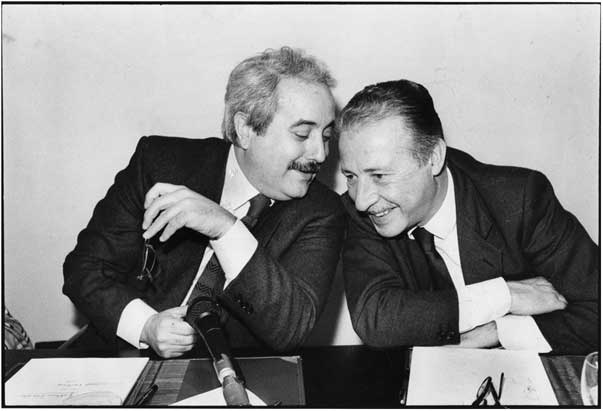

On 27 March 1992, two greying men in suits exchanged a whisper at a press conference. Touching shoulders as they leant into each other to speak and listen, the two men smiled, one loosely clasping his reading glasses, the other with arms crossed like his teacher might have taught him to do in elementary school many decades earlier. The two judges were speaking at a conference about mafia and politics at Palazzo Trinachia in Palermo, and were captured by a young photographer, Tony Gentile, working for the evening edition of Il Giornale di Sicilia. Little did they know, as Gentile clicked a sequence of five black and white shots, that those images would bind them together in a frozen whisper that would become one of the most iconic photographs in Italian history.

Figure 1 Tony Gentile ‘Falcone e Borsellino’ initially taken for Il Giornale di Sicilia, March 1992.

Gentile’s most famous photograph was not published on the evening it was taken. After the death of judge Giovanni Falcone on 23 May Gentile sent the photograph to the distribution company Sintesi, from where it reached the editorial boards of major newspapers worldwide. It was not until the assassination of judge Paolo Borsellino on 19 July that the photograph made front page news across the world and by the end of that year it had appeared in Time magazine and become a symbol of the dead judges and their struggle against the Mafia.Footnote 1

As a lasting symbol of the judges the photograph now has the status of a cultural icon. Cultural icons are visual referents for complex events and their associated discourses and they often serve to simplify and soften confusing and painful collective experiences. Barbie Zelizer discusses this mechanism in particular in reference to what she calls ‘about-to-die photographs’ which she argues ‘stand in for complex and contested public events’ because they ‘lessen the discomfort caused by viewing and enhancing identification with what is seen’ and are thus more likely to become ‘vehicles of memory’ (Zelizer Reference Zelizer2010). Although Tony Gentile’s photograph does not depict the judges in the literal final instances of their life, it brings together two violent assassinations into a single image, which the viewing public knows anticipates their imminent destruction.

Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites, in their book No Caption Needed (Reference Hariman and Lucaites2007), explore the ways iconic images serve as rhetorical devices that make demands on viewers in the present. They write that ‘iconic photographs provide the viewing public with powerful evocations of emotional experience’ (2007, 35). Photographs become iconic not only due to their wide circulation, which makes them immediately recognisable (Brink Reference Brink2000, 137) but also for the way they are able to harness emotions and spur ‘artistic improvisation and viewer response’ (Hariman and Lucaites Reference Hariman and Lucaites2007, 20). Miles Orvell, furthermore, described how the meaning of iconic images ‘is not necessarily fixed or stable over time’ (Reference Orvell2003, 213): in fact it may very well be that it is the ability of a single photographic image to allow for contradictory meanings to be projected onto it that lends it iconic status.

This paper will reflect on the ambiguity embedded in the perceived power of Gentile’s photograph as an icon, by considering the context in which it was made iconic, as well as presenting practical ways the icon has been ‘used’ in the aftermath of the judges’ assassinations. While the photograph’s iconic status at times empties it out of the very symbolic resonance social agents attribute to it, its connection to the dead bodies of the judges still lends it a dangerous power.

Tony Gentile’s photograph represents and encompasses the joint tragedy of the brutal killing of two judges by the Mafia in 1992. Vicky Goldberg has noted that iconic images ‘concentrate the hopes and fears of millions and provide an instant and effortless connection to one deeply meaningful moment in history’ (Goldberg Reference Goldberg1991, 135). Gentile’s photograph, however, does not capture the moment of the assassination of the judges but a lost moment, a time of innocence prior to the judges’ destruction. Unlike other iconic photographs where the events made visible by photography are the events being represented (see for example the famous photograph The Terror of War by Nick Ut capturing Vietnamese children running from a napalm attack) the ‘event’ Tony Gentile captured was an ordinary day in which the judges were alive together. Yet this very ordinary depiction gained extraordinary power precisely for its invisible relation to other impossibly painful images in which the judges’ bodies were conspicuously absent.

Most Italians learned the news of the assassination of both judges, Falcone and Borsellino, through the special editions of the telegiornali. These early reports on what are known as the ‘stragi’ of Capaci and Via D’Amelio, revealed the news of the deaths of the judges by focusing on the destroyed landscapes torn apart by the Mafia’s ‘Lebanese strategy’.Footnote 2 In Capaci the scene was initially filmed at a great distance, and the cars carrying Falcone, his wife and his bodyguards had to be ‘discovered’ by viewers in a landscape where five tonnes of explosives obliterated an immense stretch of highway. The Via D’Amelio reports showed panning images where the camera filmed through crowds of people, burning cars and billowing smoke before it finally focused on the exploded building where Borsellino’s mother lived and where the judge lost his life. In the news reports (website 23 maggio 1992) the bodies of the judges were only present in the imagination, replaced by signifiers of their destruction: the twisted metal of the highway, mangled cars, the debris and mud collected around the shattered vehicles in Capaci; smoke and collapsed balconies, the melted dashboard of a parked car in front of Via D’Amelio.Footnote 3 Tony Gentile’s photograph thus recomposed the shattered bodies of the judges and concentrated the collective gaze of traumatised viewers on their serene smiles.Footnote 4

In this light, Tony Gentile’s photograph of the judges is sublime. Nicholas Mirzoeff defines the sublime as ‘the pleasurable experience in representation of that which would be painful or terrifying in reality’ (Reference Mirzoeff2002, 9) and refers to the ancient statue of Laocoon and his children to illustrate this concept. While representing the judges’ total annihilation the photograph provides a positive sensorial experience in its readers as it ‘defends’ the ‘shreds of living presence’ of the judges ‘against oblivion, against death’.Footnote 5 Gentile’s photograph thus represents an act of resurrection of the dead judges, which simultaneously captures their loss and destruction.

Patrick Hagopian (Reference Hagopian2006) and Paul Lester (Reference Lester1991) have both commented on the important relationship between the moving image and still photographs. Hagopian noted how some of the most iconic images of the Vietnam war were all originally moving images from which stills were taken and yet it is in the still images of the war that memories concentrate. For Hagopian it is the stillness of the photograph that lends it its power because the photograph ‘exists in space but not in time, it can endure for the viewer. We can fix on a particular configuration of forms and we can hold it in our gaze. We can possess it and stare at it’ (2006, 213). There is no single still image from the stragi of Capaci and Via D’Amelio that the Italian public can hold in its gaze, and Gentile’s photograph manages to join the two violent events together. For Lester, ‘it is the powerful stillness of the frozen, decisive moment, that lives in the consciousness of all who have seen the photographs’ (Reference Lester1991, 120). As the ‘decisive moment’ of both the assassinations did not appear on film (the actual explosions) and viewers were presented with the confusing violent aftermath of the tragedies, Gentile’s photograph allowed the grieving public to slow down the visual loop of death and destruction presented by television and to rest on the frozen stillness of a prior moment.

Gentile’s photograph can also be read as the visual near-embrace between two men. As Hariman and Lucaites have noted, iconic images ‘provide dramatic enactments of specific positionings, postures and gestures that communicate emotional reactions instantly’; such reactions ‘create interactions that become circuits of emotional exchange’ (Reference Hariman and Lucaites2007, 36). Emerging in visual opposition to the mechanised and faceless violence of the Mafia’s destruction, the smiling near-embrace of the two judges also triggers strong emotions in viewers because it constitutes an image of idealised male bonding, which is key to a long tradition of impegno in Italy and its close association with masculinity.Footnote 6

If we are to find the ‘punctum’Footnote 7 in Gentile’s photograph, one could say it rests in the direct line going from Giovanni Falcone’s lips to Borsellino’s right eye (and hidden ear) or perhaps in the gentle tightening of Falcone’s fingers around his reading glasses. These gestures play a key role in the circuit of emotional exchange between the public and the assassinated judges perhaps because they trigger echoes of another cherished icon of Italian heroic masculinity: that of the water bottle exchange between cyclists Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali.Footnote 8 Read in parallel to each other these two icons of Italian heroism share many points in common: the focus on two male bodies ‘in action’ side by side, the suits and cycling gear which make the bodies of each pair near-identical, the notepads of the judges echoing the handlebars of the cyclists, even the eyes of Falcone and Bartali being half closed. In both cases it is a sudden and unexpectedly intimate gesture linking the two male bodies that captures the viewers’ eyes: the whisper and the bottle exchange.Footnote 9

Iconic images, according to Hariman and Lucaites, are ‘civic performances combining semiotic complexity and emotional connection’ (Reference Hariman and Lucaites2007, 36). In the days after the violent disappearance of the judges it is unsurprising that an image linking the lost bodies of the judges not only to each other but perhaps also to other symbolically encoded lost male bodies, became the image of choice to commemorate them.

Material and symbolic adaptations: afterlives of a photograph

Tony Gentile’s photograph has been appropriated, copied and satirised by a wide range of social agents. It would be impossible to discuss them all, but I will now present examples ranging from street demonstrations to official commemorations, from contemporary protests to satirical cartoons.

Gentile’s photograph came to resurrect and materially re-embody the judges almost immediately after the ‘stragi’. Following the Strage di Capaci the tree outside Giovanni Falcone’s house became the focus of a series of spontaneous private outpourings where individuals left messages and flowers dedicated to the dead judge. After the strage di Via D’Amelio, Gentile’s photograph was stapled to the tree at human height so that the bottom of the tree with its roots and half trunk appeared to be symbolic legs for the judges. Deborah Puccio-Den described how: ‘in many representations of the albero Falcone, the written pieces blend in with the ficus magnolia leaves. The branches link the anti-mafia supporters and their founder, the judge, who is embodied in the tree trunk in certain pictures’ (Puccio-Den Reference Puccio-Den2011, 55).

The symbolic recomposition of the bodies of the judges through invisible legs became even more explicit on the first anniversary of the Strage di Capaci when Palermo’s Comitato dei Lenzuoli Footnote 10 reprinted Tony Gentile’s photograph above the inscription: ‘Non li avete uccisi: le loro idee camminano sulle nostre gambe’ (‘you have not killed them: their ideas walk on, on our legs’.Footnote 11 Not only did the writing of the word ‘gambe’ sit precisely in the space where the judges’ legs should have extended beyond Gentile’s photograph, but the writing and the photograph itself were tinted with green, pink and red hues. Thus the protesters were symbolically carrying the judges on their own legs while imbuing them with ‘their’ collective new life, retrieving them from the morbid stillness of black and white and literally bringing colour back to their faces.

Just as Tony Gentile’s photograph was quickly appropriated by anti-mafia protesters as a symbol of the judges, it was similarly visually and materially incorporated in the texture of state and regional commemorations on the anniversaries of the massacres. Two examples of this explicit adaptation of the photograph can be found in the monument to Falcone and Borsellino that was placed in Palermo’s airport of Punta Raisi (renamed after the judges), and in the commemorative stamps printed on the tenth and twentieth anniversaries of the stragi.

On a wall outside the arrivals hall in Punta Raisi, Falcone and Borsellino’s photographic whisper was re-rendered in a bronze medallion inscribed with the judges’ names ‘Giovanni Falcone, Paolo Borsellino, gli altri … orgoglio della nuova Sicilia’ (‘Giovanni Falcone, Paolo Borsellino, the others … the pride of the new Sicily’). The medallion was placed in the centre of a rough map of Sicily made of sandstone slabs of different colours and sizes. Unveiled on 11 June 2002, it didn’t even last a decade in its airport location. On 23 June 2011, in fact, it was transferred to the police station in the town of Cefalù, where the artist who made the monument, Tommaso Geraci, resides. The failure of the monument reflected tensions surrounding the symbolic meaning of the judges, as right-wing politicians like Gianfranco Micciché challenged the very renaming of the airport after the judges, claiming that it confirmed negative stereotypes of Sicily as the land of the Mafia to tourists landing on the island.Footnote 12

Judges Falcone and Borsellino have been commemorated by two official stamps issued by the Italian state, respectively ten and twenty years after the Strage di Capaci. The first stamp (website I bolli 10 anniversario), issued in 3.5 million copies, was a drawn adaptation of Tony Gentile’s photograph (Fig. 2). Drawn in black-and-white, it positioned the judges shoulder to shoulder and with smiles on their faces – their names written alongside the years of their respective births and deaths. This first adaptation of Gentile’s photograph is explicitly and unapologetically focuses on the deaths of the judges. The birth and death dates of the two men evoke similar commemorations to ‘caduti’ of the Italian Resistance and other contexts.Footnote 13 There are no words relating to the work of the judges, nothing written about the mafia or the anti-mafia and the men are simply framed as hero-martyrs for the Italian state.

Figure 2 ‘Falcone e Borsellino’ stamp issued 23 May 2002. Drawing by Tiziana Trinca, for the Officina Carte Valori dell’Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato.

The second stamp (website Ventesimo anniversario) depicting judges Falcone and Borsellino was issued to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the Direzione Investigativa Antimafia (which also corresponded with the twentieth anniversary of their assassinations) (Fig. 3). In this second stamp the iconic duo of the judges (still reproduced by the order and the position of the judges Falcone left, Borsellino right) was disrupted by the presence of a third judge above and between the other two, judge Rosario Livatino. Livatino was murdered by the Mafia in Agrigento in 1990 and was in the process of being beatified by the Catholic Church when the stamp was issued. The visual disruption of Tony Gentile’s iconic image served to highlight Rosario Livatino’s sacred status among the other icons of the struggle against the mafia and produced an odd visual trinity supposedly aimed at suggesting a new chronology in which the two judges known as a ‘duo’ were to be remembered as part of a longer sequence of sacrificial victims for the state.Footnote 14

Figure 3 ‘Direzione Investigativa Antimafia’ stamp for the series on ‘le istituzioni’, issued 21 September 2012. Drawing by Maria Carmela Perrini, Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato S.p.a.

The president of Poste Italiane, Giovanni Ialongo, said that the stamp dedicated to the Direzione Investigativa Antimafia (DIA) was not only a ‘celebratory philatelic event’ but that it took on a ‘significant civil and moral value because it expresses the recognition of an entire nation to the contribution that the DIA and its investigators offer each day to the security of the Country in their struggle against organised crime’. The commemoration of the three judges is not casual, according to Ialongo, as they are ‘emblems of the struggle against the mafia and of the many investigators and magistrates that paid with their life for their commitment in defence of citizens and institutions’. In this retelling, Falcone and Borsellino are simply remembered as ‘emblems’ of the struggle against the mafia.

Activists from Palermo’s ex-Comitato dei Lenzuoli lament this paying of empty lip-service to the memory of the judges. Piera Fallucca observed that: ‘While everything is softened in the stagnant rhetoric of official commemorations, too often the anti-mafia is reduced to an institutional liturgy, celebrated in defiance of the memory of the victims and the dignity of the just’.Footnote 15 To Fallucca, such official commemorations are distasteful as they insult the memory of the victims of the mafia. In her words, the ‘dignity’ of just and honest people is set in stark contrast to the indignity of empty commemorations. For Piero Li Donni the commemorations taking place each year on the anniversaries of Capaci and Via D’Amelio are nothing but a ‘ritual whose ECG is flat’, emptied out of meaning and life (Alajmo Reference Alajmo2012, 158). Fausto Nicastro also says that:

By dint of school assignments, commemorations, shabby poems, recitals, little shows and papier maché statues, a genre that should instead be competitive in the field of ethics, the aesthetics and reason has been devalued. The risk is that what is left of civil consciences gets jammed up by inert materials. (Alajmo Reference Alajmo2012, 168)

All three of these comments use metaphors of stagnation, death and suffocation to describe the efforts of commemoration. For Li Donni, in particular, the medical metaphor of the ECG suggests the uselessness of efforts at resuscitation though it is unclear whether the patient he imagines is Italy, Palermo, the anti-mafia movement or the memory and legacy of the judges.

One recent episode in the context of a football game played in Turin on 8 May 2013, illustrates the ways Gentile’s photograph may still serve to transmit powerful ethical messages in an aesthetically pleasing way. Following the death of Giulio Andreotti, Italy’s seven-times prime minister and controversial Christian Democrat politician, Giovanni Malagó – the president of Italy’s National Olympic Committee (CONI) – ordered that players and audiences hold a minute’s silence for the politician before the midweek games of Italy’s Serie A. In stadia all over Italy the minute’s silence for Andreotti was disrupted by chants and whistling. Andreotti had been indicted for collusion with the mafia and had faced serious allegations (including suspicion of being behind the murder of journalist Mino Pecorelli in 1979) and only narrowly escaped a prison sentence when his links to the mafia were found to have ceased in 1980, and he was therefore protected by a statute of limitations. Andreotti was close friends with Salvatore Lima, a Palermo politician with explicit links to the Mafia, whose murder by the Mafia in 1992 was seen to be linked to the Maxi Trial of Mafia bosses overseen by Giovanni Falcone himself.

At the Toro-Genoa game in Turin the night of the commemorations for Andreotti, fans held up Tony Gentile’s black and white picture printed in multiple copies as an act of defiance. Interrupting a liturgical ritual of respect for the dead Christian Democrat politician, the fans symbolically transformed the immortal whisper of the judges into a silent accusation. Operating outside of the traditional memorialisations of the two judges and within the secular sphere of a football game, Gentile’s photograph became an uncanny reminder of the dead judges, whose memory was deemed to have been insulted by honorific displays addressed to Andreotti. If anniversary and official commemorations produce flat ECGs, to go back to Piero Li Donni’s observation, this stadium commemoration reanimated Gentile’s icon with the power of defibrillators.

The photograph’s material and symbolic connection to the dead judges has the capacity to ‘evoke the awe, uncertainty, and fear associated with “cosmic” concerns’ linking it to death and lending it the power of the uncanny’ (Verdery Reference Verdery1999, 31).Regardless of how often Gentile’s photograph is reproduced, it still has the capacity to draw a direct connection between the once-living bodies of the judges and the living viewers of the photograph. This icon’s power derives from its capacity to simultaneously evoke life and death. Roland Barthes saw photographs of the dead as ‘emanations of the referent’. He wrote:

The photograph is literally an emanation of the referent. From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here; the duration of the transmission is insignificant; the photograph of the missing being, as Sontag says, will touch me like the delayed rays of a star. (Barthes Reference Barthes1981, 80)

This ‘touching’, connecting the dead to the viewer of the photograph, is about more than a simple awareness that a photographed person was once alive; as with religious icons, cultural icons transmit a web of symbolic messages, which radiate into the present with reverberations of the referent. This emotional and symbolic contamination that comes from deeper encounters with an icon is quintessentially visual and functions and operates outside of language.

Bridging the visual space between photography and language, political cartoons play on the irrational and emotional power of cultural icons and often reanimate them. Cartoonists have redrawn and appropriated Gentile’s image extremely often for both silly and profound purposes and this is a testament to the photograph’s iconicity. To comment on the discourses they evoke and the political context of their production would take an entire other article. I will therefore briefly present only three examples which visually appropriate Gentile’s photograph and desecrate it in order to tap into its iconic power.

The primary visual desecration of Gentile’s icon consists of inscribing words in the judges’ mouths after death. Katherine Verdery has observed that dead bodies derive great power in politics from their silence. By symbolically rematerialising the bodies of the assassinated judges Gentile’s photograph opens up a space in which the judges can be made to speak from beyond the grave and cartoonists play precisely on the discomfort viewers may experience in ‘reading’ these blasphemous imaginings.

The comic artist Luigi Alfieri, whose pen name was Vadelfio, produced this image (Fig. 4) (website Fumetto Vadelfio) in response to the destruction of a monument to Falcone and Borsellino on the eighteenth anniversary of their death. The use of the cloud-like cartoon bubble and the Disney comic font links Vadelfio’s cartoon to the Italian children’s comic ‘Paperino’. This visual connection to a popular childhood comic icon stresses the punchline of the joke in which Falcone and Borsellino lightly comment on Italy’s failure to ‘come of age’ by remembering them properly. The cloud bubble, however, also evokes the symbolic clouds of paradise (further stressed by the fading of Gentile’s image and the cloud sectioning at the bottom) and shows the judges looking down on Italy from heaven, enjoying a joke at Italy’s expense from the sky.

Figure 4 Vadelfio (Luigi Alfieri), 2010.

In another invented conversation between the two judges, Marco Tonus’s cartoon, ‘eroi’ printed in the last edition of ScaricaBile (a satirical news website) showed a darker rendition of Gentile’s photograph (Fig. 5) (website scaricaBile). Looking like tired old crooks (perhaps even mafiosi?), smoking cigarettes, the two judges brag about being called heroes. Borsellino’s comment that he has not spoken since 1992 gains its punch power from the connection between his silence and his death but also subtly suggests that he would not be seen to be a hero had he continued to speak. Tonus thrice desecrates the heroic image of the judges: first by putting words in their mouths, secondly by visually associating them with criminals and finally by linking their heroism with silence, which in the mafia’s honour code is the highest value of ‘omertá’. This desecration of course was intentional as it was a response to a comment by Marcello Dell’Utri,Footnote 16 who had referred to Vittorio Mangano, stable keeper for Silvio Berlusconi in the 1970s and condemned for mafia activities and multiple homicide, as a ‘hero’. Borsellino himself, in his last interview, had called Vittorio Mangano one of the key links between the Sicilian Mafia and Northern Italy.Footnote 17

Figure 5 Marco Tonus, ‘Heroes’, ScaricaBile n.33, 14 July 2010.

Finally, appearing in Il Manifesto on 31 January 2013, Mauro Biani’s cartoon, entitled ‘memory’, re-imagines Gentile’s photograph as a desperate plea by the judges (Fig. 6) (website Mauro Biani). Evoking their Sicilian origins by the term ‘cortesemente’ – kindly – Biani imagines the judges addressing the readers and begging them to forget them. Only their suits remain in the imagined photograph, the judges fading away in memory and in representation, returned to the disembodied space of death and oblivion intended by the mafia and confirmed by a public unable to carry on their legacy. Mauro Biani’s cartoon uses Gentile’s icon to visually stress the photograph’s fading power as a political symbol, yet by doing so he still reaffirms its significance as a cultural icon.

Figure 6 Mauro Biani ‘Memoria’, Il Manifesto, 31 January 2013.

Conclusion

This article has aimed to illustrate the polysemous power of Tony Gentile’s icon, as a famous image of the judges that is used by a wide range of social agents to represent a similarly wide set of symbolic discourses. All cultural icons are at once ‘sacred images for a secular society’ and hollow ‘stock images’ (Hariman and Lucaites Reference Hariman and Lucaites2007, 1–2). They can be framed in offices, plastered on ships,Footnote 18 flown from courthousesFootnote 19 and flashed up in car adsFootnote 20 or filmsFootnote 21 , but it is their power to provoke emotion (for its own sake or for the sake of action) that allows them to continue to ‘walk on our legs’ into the future.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Martina Caruso and Dr Alessandra Antola for their tireless work on this special issue and the anonymous reviewers of this article for their thoughtful, helpful, and detailed suggestions and insights. My special thanks go to Tony Gentile for his kind permission to publish his powerful photograph as well as to Luigi Alfieri, Marco Tonus and Mauro Biani for their comics. Dott. Anna Maria Morsucci at Poste Italiane and Dott. Maria Antonietta Moretti from the Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico were invaluable in getting permission to publish the stamps. Publisher Ottavio Navarra helpfully granted permission to cite from Alajmo’s work. Dott. Eugenia Testa as always provided generous and focused advice on copyright issues. Dr Federica Mazzara was a precious scout for disappeared airport monuments. Steven Hinds was a patient and generous copy editor and invaluable listener. I thank them all from the heart.

Note on contributor

Dr Eleanor Chiari is programme convenor for the BA in Language and Culture and Teaching Fellow in the School of European Cultures and Society at University College London. She teaches courses in cultural studies, visual culture, and the politics of memory. Her first book entitled Undoing Time: The Cultural Memory of an Italian Prison focused on Turin’s prison Le Nuove and was published in 2012.