MONUMENTAL INSCRIPTIONS ON THE ANTONINE WALL

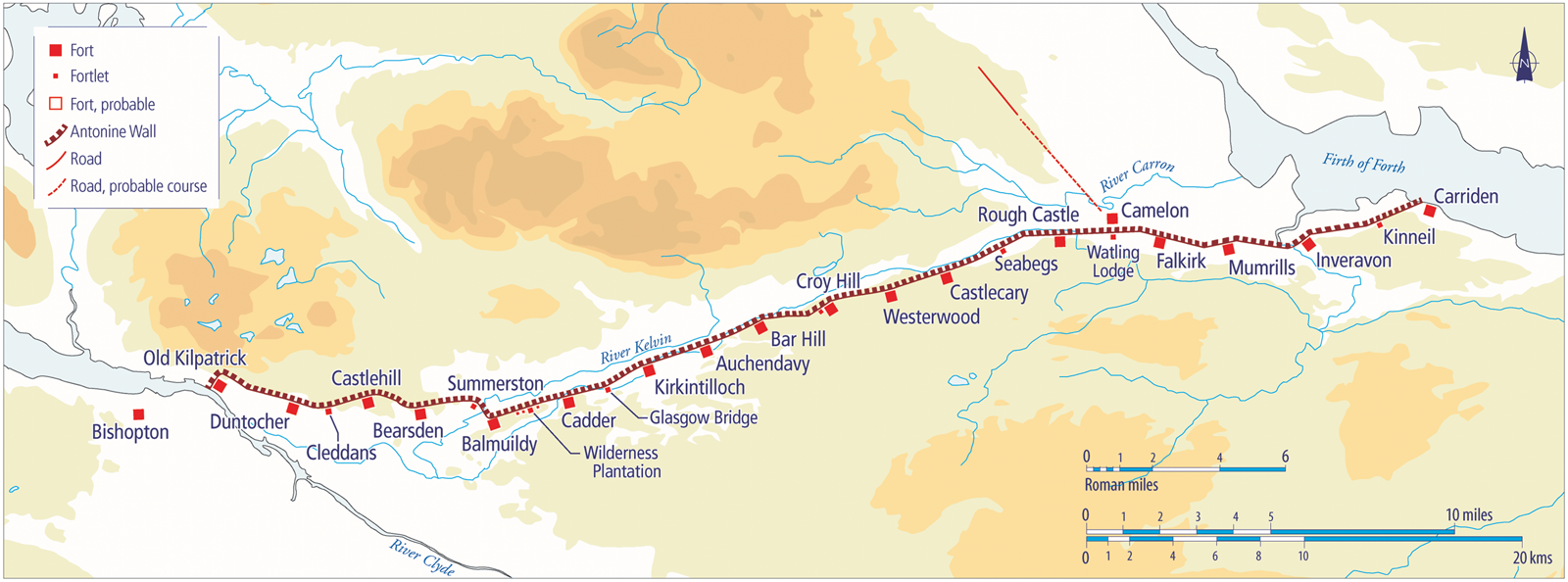

The Antonine Wall marked Rome's north-western frontierFootnote 1 and is incorporated into the ‘Frontiers of the Roman Empire’ UNESCO World Heritage Site (fig. 1). It is a turf rampart set on a stone base that cleaved a route across the Forth-Clyde isthmus for some 37 miles and separated the Roman-controlled region to the south from the non-Roman northFootnote 2 with outpost and advance forts to the north. Monumental inscriptions have been recovered from along the line of the wall and its environs.Footnote 3 They constitute the most impressive and visually impactful body of epigraphic evidence recovered from any Roman frontierFootnote 4 and many combine inscriptions and iconography in relief. The monuments are carved from locally sourced sandstone and contain identifiable patterns of epigraphic practice in prescriptive abbreviated Latin. The known examples are dedicated to the emperor Antoninus Pius, who commissioned the mural barrier around a.d. 142. Most record the distance constructed by three legions (legio II Augusta, legio VI Victrix and legio XX Valeria Victrix), normally stationed at York, Chester and Caerleon. Many include legionary emblems such as a boar for Legion XX and Capricorn or Pegasus for Legion II. The more elaborate examples also contain relief imagery depicting the invasion and conquest of southern Scotland, including the subjugation of troublesome northern tribes and religious practice incorporating the legions’ favoured deities and rituals.

FIG. 1. Plan of the Antonine Wall. (© David J. Breeze, used with permission)

I have argued elsewhere against the use of binary terminologies, such as Roman:native, traditionally applied to investigations of the interaction between Romans and Iron Age peoples in northern Britain, since they perpetuate a negative and derogatory categorisation of indigenous non-Roman populations.Footnote 5 I would caution that similar care should be taken with the terminology applied to the Antonine Wall relief sculptures, commonly referred to as ‘Distance Slabs’. Such language conjures an outmoded and inappropriate notion of this body of material culture as bland, uninspiring, functional blocks of stone devoid of any character or intrinsic cultural significance. Even the most cursory of checks will confirm that these are unique and exceptional examples of monumental relief sculpture (fig. 2), which will hereafter be referred to as ‘Distance Sculptures’ or ‘Distance Stones’.

FIG. 2. Bridgeness Distance Sculpture. (© National Museums Scotland)

These monuments serve various functions, primarily as visually impactful propaganda tools to commemorate the Roman conquest of, and authority over, the region.Footnote 6 The precision of recorded measurements memorialised in the inscriptions is indicative of the Roman army's concern for accuracy and could also hint at a medium for stoking competition between legions constructing segments of the wall while simultaneously reinforcing their allegiance to the emperor in line with the increasingly honorific character of Distance-Stone dedications approaching the third century.Footnote 7 Critically, given the comparatively short-lived occupation of the Antonine Wall, they place us in a most fortuitous situation by providing a rich and tightly dated body of evidence through which to investigate the unique and culturally dynamic context of life on the frontier without resort to extrapolation based on chronological and regionally distinctive stylistic practices.Footnote 8

Of the 19 known examples, 16 Distance Sculptures and one plaster cast are held in the collections of the Hunterian Museum at the University of Glasgow, another is in the Glasgow Museums collections, while the most easterly, and arguably most extravagantly decorated, is held by the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. Many of the Antonine Wall inscriptions were donated to the University of Glasgow (and then transferred to the Hunterian Museum) by antiquariansFootnote 9 and landowners during the 17th and 18th centuries; other inscriptions recovered during the construction of the Clyde-Forth Canal were donated to the Hunterian by the Canal Commission.Footnote 10 While the contexts of the Distance Sculptures’ original discovery are not always recorded with precision and we cannot state with certainty the circumstances of their original placement along the wall, the presence of cramp-holes on the rear of many confirm that they were mounted onto another structure for stability.Footnote 11 To ensure their accessibility and visibility to the widest possible audience, the sculptures were most likely fixed to the southern face of the wall, probably at high-traffic crossing pointsFootnote 12 or in forts, though the find-spots might suggest they were not ultimately deposited at or close to forts. It is even possible that they were positioned along the Military Way to maximise their impact and accessibility.Footnote 13

Monumental relief sculptures are an important medium through which Roman artists provided background and cultural context to mythological, religious or historical events, such as the iconic scenes of the Roman army on campaign depicted on the columns of Trajan and of Marcus Aurelius in Rome.Footnote 14 The variety of topics encapsulated in relief defies neat categorisation of the genre,Footnote 15 but the incorporation of iconography and epigraphy in the Antonine Wall sculptures combines commemoration, memorialisation, monumentalisation and propoganda. The practice of producing monumental inscriptions was most prolific during periods of social change, particularly the early centuries a.d,Footnote 16 a time frame that aligns most fortuitously with Antoninus Pius’ campaigns in northern Britain,Footnote 17 since the stones preserve a record of this militarised region on the boundaries of empire.Footnote 18

Because of their perceived permanence, in being carved from durable material, monumental inscriptions served as an ideal medium for publicising and preserving the actions and reputations of dedicators long after their death.Footnote 19 In other words, monumentality was a mechanism for immortality.

By inscribing combined dedications both to the emperor and to memorialise themselves,Footnote 20 the legions that commissioned these sculptures were effectively aligning their own noble deeds in pursuit of the glory of Rome with those of the emperor, ‘Father of his Country’. At the same time, the monuments performed a critical role of physically, visually, conceptually and permanently stamping the Empire's irrevocable rights to the captured territories in northern Britain through a commonly employed medium for endorsing ancient treaties.Footnote 21 Their placement in high-traffic areas in order to engage the widest possible audience of both Roman and non-Roman participants would have continually validated and reinforced Rome's authority. Further, embedding the message onto large dressed stone lent a degree of permanence to what may have been perceived as an ephemeral frontier structure. Monumental sculpture encapsulates the interplay between inscribed text and iconography to create a sense of audienceFootnote 22 with variable layers of access to the meanings folded into and permeating through the stone.

Sculpted figures on the northern frontier reflected the heterogeneous character of the Roman army and promoted shared identities of ‘Romanness’ in militarised regions.Footnote 23 The conceptualisation and visual iconography on the Distance Sculptures, which depict various scenes of religious practices and of violence perpetrated by a powerful incoming imperial army imposing its dominance and superiority over submissive, naked and powerless indigenous warriors, would have been alien. However, the intended message of Roman authority and futile resistance could hardly have been missed by local peoples encountering the sculptures, especially if the scenes were brought to life in authentic colour. This would have been incredibly powerful imagery emblazoning itself into the consciousness of an Iron Age audience unfamiliar with such realistic representations of warfare. Even people of Roman affiliation engaging with the sculptures would potentially have faced difficulties in understanding them, depending on their ability to read Latin, particularly the abbreviated format of Latin inscribed on the monuments.

POLYCHROMY ON ROMAN RELIEF SCULPTURE

Roman paintings on wall-plaster are well attested across the Roman Empire, with the plethora of exquisitely, if tragically, preserved frescoes from the walls of Pompeiian villas exemplifying the practice.Footnote 24 Recipes for the pigments used as well as techniques for their preparation and application survive from contemporary writers, most notably PlinyFootnote 25 and Vitruvius.Footnote 26 The techniques of painting as well as pigment identification have recently been comprehensively studied.Footnote 27

Colourful pigments survive from Classical Greek statuary,Footnote 28 including the exquisite marble sculptures from the Athenian Parthenon displayed in the British Museum. Several retain residual traces of their original pigmentationFootnote 29 in concealed crevices, despite the best efforts of museum staff to ‘clean’ the surfaces vigorously using a combination of water, acid, copper brushes and copper chisels periodically between 1811 and 1938.Footnote 30 Polychromy on Roman sculptures is similarly well attested through various sources, including small traces of extant pigment on bronze,Footnote 31 marble statuaryFootnote 32 (such as the exquisite painted Amazon head from HerculaneumFootnote 33) and sarcophagi.Footnote 34 The practice is even evidenced on a rare intaglio depicting a Greek artist applying colour to a Roman sculpture,Footnote 35 and several Pompeiian frescoes depict painted statues.Footnote 36 This has led to a burgeoning scholarly interest in colour on classical sculpture.Footnote 37 That interest has been gathering momentum and now extends to international symposia dedicated to understanding polychromy on ancient sculpture and architecture, most recently that hosted at the British Museum,Footnote 38 annual meetings of the Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity (ASMOSIA)Footnote 39 and conferences exploring the applicability of scientific technologies for the identification of pigments on artwork and archaeological materials.Footnote 40 Poor survival of the pigments due to post-depositional processes make their authentic reconstruction challenging,Footnote 41 but these recent transdisciplinary approaches, combining archaeological investigation with scientific analysis, allow for the characterisation of compounds, often from microscopic remains.Footnote 42

Though polychromy on Roman reliefs is increasingly drawing scholarly attention,Footnote 43 the focus of this interest is generally directed at marble sculpture, such as the Ara Pacis in Rome or the marble frieze from Nicomedia, in modern-day Turkey (fig. 3), which depicts Roma, Victory, togate Roman citizens and the co-emperors Diocletian and Maximian participating in the adventus procession.Footnote 44 The survival of pigment on many stones, such as locally quarried sandstone used for relief sculptures in northern Britain, has been poor to non-existent. The practice of applying pigments to sandstone relief is, however, known from ancient Egypt, as evidenced by the recent recovery of a relief sculpture of Ramses from the temple of Kom Ombo dating to c. 1279–13 b.c.Footnote 45

FIG. 3. Polychromy on a marble relief from Nicomedia (Sare Ağtürk Reference Sare Ağtürk2015, fig. 4). (Reproduced with the kind consent of T. Sare Ağtürk)

The Roman Distance Sculptures and other worked stone recovered from the environs of the Antonine Wall serve as excellent examples of Roman relief sculpture on sandstone. The inscribed texts on the Antonine Wall sculptures operate symbiotically with the dramatic, often brutally violent, iconography carved into them as powerful propaganda tools. These monuments perform a complex role in the transmission of information in a variety of ways to different audiences and demand critical engagement. Whether they are understood through the prism of their material propertiesFootnote 46 or through the concept of materialityFootnote 47 or how they perform and transform in different cultural contexts,Footnote 48 they are imbued with vitality and significance relating to the interface between people and things beyond their inherent material properties.Footnote 49 As such, they must be considered within the sphere of relational, mutually dependent, symmetrical entanglements between things and people.Footnote 50 Their cultural significance transcends functionalist descriptive accounts of their epigraphic content or artistic merits and even the skill of the artisans, whose work demonstrates a comparatively greater degree of competence in their representation of animals than of humans in the various scenes depicted.

These monumental inscriptions offer opportunities to explore connections and disconnections of operational sequences within the concept of the chaîne opératoire,Footnote 51 taking account of the inherent properties of the raw material and the modifications necessary to achieve the desired results within the context of inherited ways of doing and the passing on of technological traditions.Footnote 52 Two examples discussed below from Summerston Farm and Bridgeness demonstrate some striking similarities that could well be indicative of the passing on of skills from one artisan to another or, more likely, the development of artistic and technological skills in one individual.Footnote 53 Understanding of the chaîne opératoire can be taken to an additional level through consideration of the deliberate choices of pigments; these were apparently prescriptively applied in specific contexts to ensure that the sculptures complied with culturally ascribed traditions. The apparent difference between the products of Mediterranean artists, who sculpted exquisitely rendered and idealised images from marble, and those of frontier artisans, who worked locally sourced sandstone, might not be suggestive of the culturally ascribed choices or skills of the sculptor, but imposed by the friable character and possibly unfamiliar medium of the latter material. Here the application of pigments may well have been a useful mechanism to conceal imperfections and to provide an element of realism that would otherwise be challenging to achieve on this raw material.

Visible traces of colour are rarely referred to by curators and conservators, though glimpses have occasionally been snatched when the Antonine Wall inscriptions were wet during cleaning in preparation for new museum exhibitions. Lawrence Keppie notes that inscriptions were ‘thoroughly cleaned’ in preparation for a visit by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1849, ‘washed in distilled water’ in 1976 and ‘cleaned with a detergent recommended by the National Museums of Scotland’ in 1979.Footnote 54 A note from a National Museum of Scotland (NMS) curator refers to steam-cleaning of the Bridgeness sculpture in 1999 (see fig. 5). These actions, though well intentioned, combined with the harsh acidic Scottish soils threaten the survival of fragile pigments. Further, it is possible that residue from the detergents may mask residual pigment traces.

PXRF AND RAMAN SPECTROSCOPIC ANALYSIS OF THE DISTANCE SCULPTURES

The research presented in this paper stems from exploratory portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) analysis undertaken by the author in 2013 on a Distance Sculpture dedicated by Legion XX, but of unknown provenance, and held in the collection of the Hunterian Museum (RIB 2173).Footnote 55 Following cleaning, gilding on the lettering as well as painting of the peltae in a dark-brown colour became visible. The results of the pXRF analysis confirmed several spots rich in lead, iron, copper and cobalt, as well as gold, all of which are reported as deriving from the stone's repainting and gilding during the 16th century when it was embedded into the fabric of Dunottar Castle on the north-east coast of Scotland.Footnote 56

The aim of this present study was to use in-situ non-destructive analytical techniques to investigate whether any traces of pigments originally applied to the Antonine Wall monumental inscriptions during the Roman occupation of Scotland in the second century are detectable. As a first step, pXRF was used; this is now widely and successfully employed in archaeology and heritage and conservation scienceFootnote 57 in order to provide non-destructive elemental analysis of materials such as pigments, including minerals and earths. While the technique can classify pigments that are, for example, rich in iron or copper, it cannot provide a full identification of a pigment (the complete compound), such as haematite (iron III and oxide) and azurite (copper-carbonate mineral), and nor can it be used to analyse organic-based pigments such as madder, rubia tinctorum. Portable Raman spectroscopy was used to overcome these limitations. Nonetheless, this technique presents its own challenges in interpretation since some pigments absorb source laser wavelengths and cause large fluorescence backgrounds that obscure Raman signals. These challenges are compounded by the characteristics of the materials under study which can be problematic for Raman to detect: i.e. heavily diluted pigments combined with the quartz-rich and heterogeneous character of the sandstone from which the sculptures are carved can prove difficult to ‘fingerprint’ and influence analytical results.Footnote 58 The Raman Spectroscopic Library of Natural and Synthetic PigmentsFootnote 59 and recent work that has provided a Raman spectroscopic library of medieval pigments,Footnote 60 as well as other reference sources,Footnote 61 have been enormously helpful for this analysis, though the challenges set out above make the acquisition of comparably ‘clean’ results devoid of background noise a rarity. This report summarises the pXRF and Raman results, and draws out some conclusions before presenting a palette of colours originally applied to these monuments and a digital reconstruction of one iconic scene from the Bridgeness sculpture.

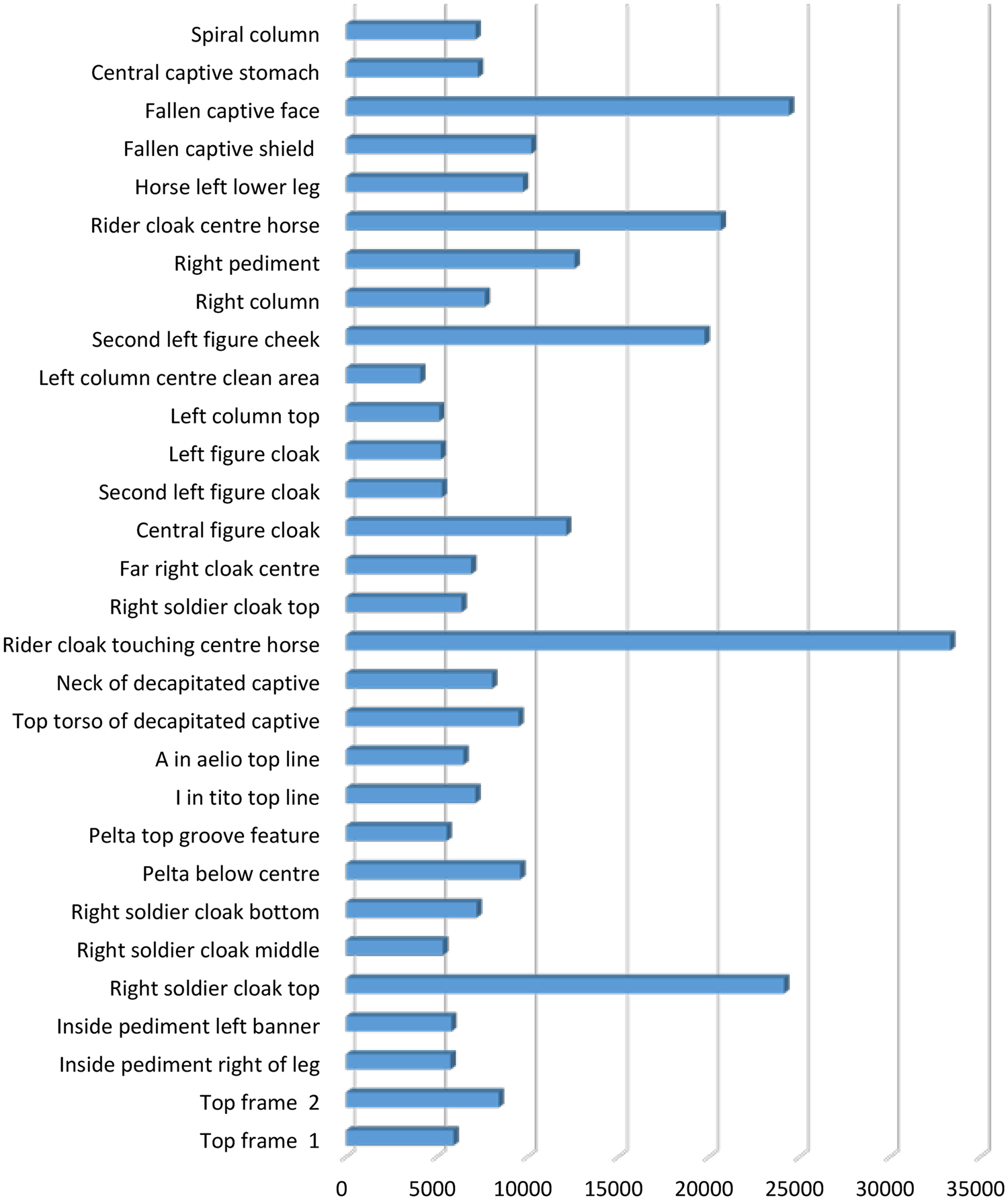

The pXRF instrument used was a Niton XL3t 900 SHE GOLDD Alloy Analyser, with a 50 kV Ag X-ray tube, 80 MHz real-time digital signal processing and two processors, for computation and data storage respectively. Analyses were undertaken in the TestAllGeo calibration within the Soils and Minerals mode with resolution of c. 165 eV at 35 KeV. Many of the 40 elements the instrument can in principle detect were present at concentrations below the elements’ limit of detection (LoD) or were light elements whose fluorescent peaks at low energies were poorly resolved at low concentrations (Mg, Cl and S); the latter had a value of <10,000 ppm, which is likely spurious. The remaining 16 elements were determined semi-quantitatively at a level significantly above the background levels in untreated areas of the stone, with attention focused predominantly on eight elements deemed to be most relevant based on their detection levels and common presence in pigments from the Roman era (see tables 1 and 2). The element concentrations are recorded in parts per million (ppm) for some (Pb, Mn and Ti) and as weight per cent for others (Fe, Ca, K, Al and Si). The surface topography of the sandstone was challenging, being roughly cut, and many analysis spots were on points of relief or on the grooves of lettering or decoration. An additional issue that required mitigation was the variety of textures and colours naturally present on the sandstone that were reflected chemically in a range of background levels of certain key elements, notably iron.

TABLE 1 SELECTED COMPOSITIONS DETECTED BY PXRF ANALYSIS OF THE SUMMERSTON FARM DISTANCE SCULPTURE

(* = poor analysis due to surface conditions; <LoD = below limit of detection; results highlighted in grey denote elevated levels of the corresponding element)

TABLE 2 SELECTED COMPOSITIONS DETECTED BY PXRF ANALYSIS OF THE BRIDGENESS DISTANCE SCULPTURE (<LoD = below limit of detection; results highlighted in grey denote elevated levels of the corresponding element)

Raman spectroscopic analysis is also becoming increasingly utilised in archaeology, heritage and materials science.Footnote 62 Raman directs light through a monochromatic photon beam (a laser) onto a sample, causing some of the resulting photons to interact with the sample and the scattering of light in two ways. The Rayleigh scattering has the same energy as the incident light and provides no information on vibrational energy levels contained in the sample. Inelastic scattering refers to the emission of a photon with an energy that lies either above or below the Rayleigh scatter and produces frequency-shifted ‘Raman’ photons. The Raman spectrometer measures any altered wavelength of photons dependant on the sample under study.Footnote 63 Raman analysis was undertaken on the sculptures in order to progress from the pXRF-determined elemental characterisation of a decorated layer as being, for example, iron rich, to a fuller compound identification, such as haematite, or to the detection of a preparative layer on the stone, such as gesso.Footnote 64 It was also desirable to apply a non-destructive technique that may in principle identify organic-based pigments, such as madder, that pXRF cannot.

The Raman instrument, a handheld SciAps Inspector 500 with a 1030 nm laser, was held against the surface of each object at defined spots that corresponded as closely as possible with the pXRF points of analysis. These were analysed rapidly and non-destructively. The SciAps Inspector 500 has been predominantly used in pharmaceutical, plastics and other fields; in the cultural-heritage sphere, it has been used to analyse Roman marble sculptures.Footnote 65 The programme of analysis reported here is exploratory and revolutionary, as it represents the first application to ancient sandstone statuary. As expected, the technique encountered some issues, including the heavily diluted character of any potentially surviving pigment and the masking of peaks associated with some pigments.

THE DISTANCE SCULPTURES

Nine distance sculptures in the Hunterian Museum and the Bridgeness sculpture in the NMS were analysed to provide a comprehensive comparative dataset, along with stone columns from Bar Hill fort. Altar stones and a statue from locations on or near Hadrian's Wall, now in the Great North Museum in Newcastle and Yorkshire Museum, York, were also included for comparative purposes and will be published separately. This present discussion will focus on the Summerston Farm (Hunterian Museum object number F.5) and the Bridgeness (NMS object number X.FV 27) Distance Sculptures, since published accounts confirm visible traces of pigment on both.

Summerston Farm Distance Sculpture from near Balmuildy

The Summerston Farm sculpture (RIB 2193Footnote 66) is carved from buff sandstone and was erected by Legion II to commemorate the construction of a section of the Antonine Wall between Balmuildy and Bogton (fig. 4).Footnote 67 It features a central panel with an inscription: IMP CAES TITO AELIO HADRIANO ANTONINO AVG PIO P P LEG II AVG PEP M P IIIDC LXVIS (For the emperor Caesar Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Augustus Pius, Father of his Country, the Augustan Legion II built (this) over a distance of 3666 ½ paces).

FIG. 4. Summerston Farm Distance Sculpture. (Reproduced with permission from the Hunterian Museum)

The panel on the left depicts a winged Victory holding a laurel wreath and preparing to crown a horseman who rides down two naked, bearded and bound captives. On the right-hand panel an eagle perches on the back of a Capricorn, the emblem of Legion II, above another bound captive. The compositions of the letters in the central panel and the scene in the left panel are strikingly reminiscent of the Bridgeness stone (fig. 2), on which a mounted horseman rides down indigenous warriors whose shields lie strewn around them. The critical difference is the context: the scene played out on the Bridgeness sculpture is a brutal one, with naked indigenous warriors cut down and decapitated in the heat of a battle; the Summerston Farm scene depicts events after battle, with the local warriors now captured, bound and immobilised while the solitary Roman participant is adorned with honours from the goddess Victory in recognition of his successful exploits. It has been suggested that the same soldier is represented on both sculptures, in a ‘cinematic’ depiction of him enacting progressive stages of conflict.Footnote 68

This Distance Sculpture was chosen for intensive analysis due to Keppie's note that traces of red colourant on the left panel and the inscribed lettering were observed during cleaning in 1976,Footnote 69 and these remain partially visible today.

Elements detected in relatively high concentrations by pXRF analysis are presented in table 1. This confirms a cluster of lead well above background (400 ppm) on some features on the left panel (5-1, 5-2, 5-40, 5-41, 5-42, 5-43 and 5-46) and one spot on the right panel, highlighted in yellow. Most of these spots are on the chests of indigenous warriors (see fig. 8). There is no visible residue of colour at these locations, but the results suggest they were painted with a pigment high in lead, such as minium lead oxide/red lead (dilead(II) lead(IV) oxide: Pb3O4), a bright, vibrant red. Alternatively, though less likely, the high lead content could indicate chance contact of the stone with lead or lead-rich material since the time of its deposition. Corresponding results from comparative analysis using an additional pXRF, a Bruker Tracer III-SD, support the former proposal, since the Bruker confirmed the presence of lead, though at a very low level and without any high spots in the sandstone.

Critically, all spots high in lead are in significant locations, concentrated on Victory's dress, on the hair, cheek, chests and thigh of the captives on both the left and right panels, and on the beak of the eagle on the right panel. This strongly suggests that minium was used to depict blood resulting from battle prior to the capture of the prisoners and perhaps the eagle's beak was bloodied as a symbol of Rome feasting off the blood of her enemies.

Natural iron content is c. 0.20 per cent, and one spot on Victory's dress with a value of 0.25 per cent may not provide confirmation of the presence of iron-rich pigment. The Bruker did, however, detect higher-than-background iron in at least one of the letters (last N of Antonino), on Victory's dress and behind the rider's head (which may represent a military standard held by the rider where sculptural details have worn away). Visible traces of red here are suggestive of a high iron oxide red being applied, though there remains the potential for pigments to have leached into unintended areas post deposition.

The Raman results (see table 3, below) suggest the presence of yellow orpiment (arsenic(III) sulphide)Footnote 70 on Victory's dress, which was trimmed with white lead (lead(II) carbonate 2PbCO3.Pb(OH)2). A total of 35 spots across various features were analysed on the left panel, seven on the right panel and 86 on the letters. Each spectrum was examined, and principal peaks were noted with comparisons made with the spectrum of a ‘clean’ background spot on the right side exterior, close to a cramp socket.

TABLE 3 RESULTS OF RAMAN SPECTROSCOPIC ANALYSES OF THE SUMMERSTON FARM AND BRIDGENESS DISTANCE SCULPTURES

Collectively, the spectra show peaks in the 469–75 cm-1 region, which corresponds to quartz. A peak at 1,161 cm-1 is evident at several significant spots, including several letters, the rider's ‘standard’, cloak and foot, Victory's face and the stomach of the captive on the right. This peak corresponds with madderFootnote 71 and suggests that madder was used as a locally sourced alternative to the vermilion commonly used on other Roman stone inscriptions and sculpture. Peaks associated with the presence of iron oxides, notably at 610 cm-1, are absent from the data generated by the equipment's associated Bio-Rad software, but are evidenced in the data produced by the more commonly used NuSpec software, as are several instances of peaks at 1,600 cm-1. Thus, an absence of identifiable peaks at 610 cm-1 need not be equated with an absence of iron-rich colourant; rather, the Raman analytical technique struggles to detect such a colourant at low concentration. This is confirmed by experimental work undertaken during this research that detected only very weak peaks at c. 300 cm-1 and 610 cm-1 in the analysis of replicas employing moderate to high concentrations of iron oxide/red ochre. Recent work has further verified that red ochres, which are a mixture of iron oxides, clays and silica, are more challenging to detect through Raman than haematite.Footnote 72 No lead compounds have been detected.

A poorly defined peak of low intensity at c. 350 cm-1 is common, especially on some of the lettering. This could be orpiment, a yellow-orange mineral that contains arsenic and which gives a golden lustre, with a Raman peak at 354 cm-1. Alternatively, and here suggested as most likely, it could be realgar (arsenic(II) sulphide), a striking ruby-red mineral which is usually found alongside orpiment and referred to by Pliny (HN 35.22) as sandarach, with a Raman peak at 356 cm-1. Given that this peak appears in association with the 1,161 cm-1 peak for madder, it is possible that a small amount of realgar was mixed with madder to produce a deeper red pigment. The Roman practice of mixing organic dyes such as madder and indigo to give a purple pigmentFootnote 73 or cinnabar with haematite (to extend the more valuable and challenging to produce cinnabar) corroborates this suggestion.Footnote 74 The 350 cm-1 peak on the centre fold of Victory's dress is strong and combines with a high iron spot nearby detected by pXRF. This could confirm that Victory's dress (see fig. 8) was coloured with yellow orpiment in the centre (and trimmed in white); such a colour scheme is depicted on the Pompeiian frescoes, for example that at the Inn of the Sulpicii, Murecine.Footnote 75

Bridgeness Distance Sculpture from West Lothian

The Bridgeness monumental inscriptionFootnote 76 (RIB 2139Footnote 77) is an exquisitely preserved sculpture (fig. 2) carved from buff sandstone. It is the largest known of the Antonine Wall Distance Sculptures and the most easterly example. An inscribed central panel is flanked on either side by peltae with griffin-head terminals. The left panel depicts a mounted rider under an archway in full military armour with his cloak flowing behind him; he is carrying a spear in his right hand which is poised to strike four naked northern warriors whom he appears to be galloping over in the midst, or immediate aftermath, of battle. The spears, shields and swords of the fallen warriors lie strewn around them; one warrior is lying on his back still holding his shield, while another has what appears to be a pilum lodged in his back;Footnote 78 a third has been decapitated and a fourth stares forward toward the viewer striking a contemplative pose. The panel on the right depicts a religious scene, with Roman members of the dedicating legion (II Augustan, as confirmed by the text on their standard) offering sacrifices and libations to the gods on altars under a temple pediment. Led by the legionary legate, A. Claudius Charax,Footnote 79 who is pouring a libation onto an altar, they appear to be celebrating suovetaurilia (a ritual cleansing of the legion, its personnel and standards involving the sacrifice of a sheep, a bull and a pigFootnote 80), accompanied by music being played on a flute.Footnote 81 The dedication reads: IMP CAES TITO AELIO HADRI ANTONINO AVG PIO P P LEG II AVG PER M P IIIIDCL II FEC (For the emperor Caesar Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Augustus Pius, Father of his Country, the Augustan II Legion (built this) over a distance of 4,652 paces).

As discussed above, the Bridgeness text is comparable in format, content and composition to that on the Summerston Farm Distance Sculpture and the left-hand panel is similar in terms of composition, if not content. On the Bridgeness monument we have a rather terrifying image of warfare in the heat of a brutal battle. It is perhaps significant that the religious context of this stone is restricted entirely to the panel on the right, with a structured scene involving multiple participants that is reminiscent of the relief sculpture of Trajan's Column, though the Bridgeness relief differs markedly in terms of composition, formFootnote 82 and articulation. Thus, we have religious symbolism on both sculptures, but set in slightly different contexts. On the one hand, by incorporating the familiar juxtaposition of victory and piety on the right panel,Footnote 83 the Bridgeness sculpture depicts ritual cleansing of the army in a temple setting before or, more likely, immediately after the battle that is played out on the left panel; this was probably a cleansing of the site in advance of the wall's construction.Footnote 84 On the other hand, the Summerston Farm sculpture synoptically represents battle and triumph by depicting Victory honouring the deeds of the eques in a scene devoid of the temple setting which takes place after the battle has been won and under the gaze of the captives taken prisoner during that battle. This is a familiar scenario on Roman frontier sculpture, which derives from Greek prototypes, though, intriguingly, the frontier reliefs depict non-citizen auxiliary riders as opposed to legionaries.Footnote 85

Joanna Close-Brooks notes that ‘washing the accumulated dust and grime from the front of the Bridgeness sculpture revealed faint traces of red paint in parts of the carving, traces of which now appear pink, and which showed up most clearly when the stone was wet.’Footnote 86 The NMS curator further corroborates this by recording extant red pigment in several areas following steam cleaning in 1999 (fig. 5). It is possible that the production of plaster casts of this sculpture, such as the one on display in the Hunterian Museum, could have removed extant traces of pigments from the surface. This sculpture is currently embedded into the fabric of the wall of the Roman display at the NMS, approximately 2 m above floor level. This placement provided very few options from which to define a ‘clean’ area for calibrating background readings. Iron content is >1 per cent in several areas, but a value of >2.0 per cent is here considered to be representative of an iron-rich location where pigment was applied.

FIG. 5. Bridgeness Distance Sculpture with areas of visible red pigment observed by the NMS conservator highlighted and a note by the curator on steam cleaning.

Elements detected in relatively high concentrations are presented in table 2. The results confirm five locations with higher-than-background levels of iron (fig. 6), many are centred round the rider's cloak and have correspondingly higher-than-background manganese contents. The cheek of the second-left figure is distinguished by 2 per cent iron together with high manganese, titanium and potassium contents; the raised level of the last two of these elements may be due to inclusions in the sandstone and have no connection with proposed pigments. The anomalously high potassium on the right soldier's cloak might be similarly assigned, though it is interesting to note that high levels of these specific elements appear consistently together. Extant visible traces of red on this particular cloak combined with the presence of high iron here and on the rider's cloak strongly suggest the application of iron-oxide red ochre pigment to colour the cloaks of the Romans.

FIG. 6. Iron contents of analysis spots on the Bridgeness Distance Sculpture.

There are scattered spots of lead above 100 ppm on the top frame, the A in AELIO, the neck of the decapitated northern warrior, the right pediment and the shield of the fallen captive warrior. Traces of red pigment are visible on the neck of the decapitated fallen warrior, and the presence of high lead here and on the fallen captive's shield is consistent with red pigment traces found on the captives on the Summerston Farm sculpture and suggest the application of minium (red lead) to depict blood. Its presence on the top frame and pediment is consistent with results of comparative analysis undertaken during this research on an altar to Mithras from the Great North Museum, Newcastle, where evidence of red vermilion (Hgs = mercury(II) sulphide) painted onto gesso is clear on the architectural features.Footnote 87 This suggests minium may have been used to colour the top frame and pediment.

The absence of high calcium and sulphur contents from the Bridgeness sculpture may indicate a lack of gesso (calcium sulphate) or, more likely, the removal of residual pigments and gesso by episodes of cleaning.

Turning to the Raman results summarised in table 3, a total of 39 spots were analysed on this sculpture: five on the letters and the remainder on other sculptural features. Again, the placement of the stone meant that a true ‘background’ reading could not be confidently identified for comparative purposes.

As expected, the spectra reveal the presence of quartz at 469–75 cm-1 as well as some peaks at 1,161 cm-1, which indicates the presence of madder, and at 610 cm-1, indicating iron oxide. Analysis of a spot on the captive's neck gave a small peak at 1,092 cm-1, which is very close to that at 1,095cm-1 found in sandstone alone but also close to the 1,088 cm-1 peak for calcite (calcium carbonate), which suggests a gesso layer. The peak at 1,008 cm-1 in the area of the right cheek of the horseman is potentially interesting since it is absent from the sandstone and is close to where pXRF found high iron (also on the rider's cloak) but calcium at background level only; indeed, pXRF detected no evidence for the use of a gesso layer.

On balance, and taken together with the evidence of the 1,003 cm-1 proposed yellow ochre hair on a Sol Gorgon from York that was produced during comparative analysis, the 1,008 cm-1 peak suggests that yellow ochre (fig. 7) was applied as a layer on top of gesso to produce a skin-tone colour on the rider's face. This corresponds with analysis of a painted marble head of Caligula in Copenhagen, dating to c. a.d. 37–41, which retains traces of several natural pigments in egg tempera as a binding agent.Footnote 88 These include madder between the lips and a blend of violet-purple madder root and white on the lower eyelid, with ochre earth and chalk on the skin. The artist employed various techniques to create realistic skin tones in the style of contemporary Egyptian mummy portraits, including the layering of natural pigments (brown, red and yellow ochre with chalk). It is highly likely that similar techniques employing natural pigments applied over a layer of gesso were adopted for the Bridgeness and other sculptures from the Antonine Wall in order to create realistic skin tones on figures.

FIG. 7. Raman spectrum of yellow ochre (Marucci et al. Reference Marucci, Beeby, Parker and Nicholson2018, 1231).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUDING REMARKS

A prescriptive formula for colours expected to appear in specific contexts on Roman frontier relief sculptures is evident, though it is not possible to determine whether the practice of colouring features in specific shades was determined by availability of materials, selectivity by the artist or craft traditions. For example, traces of red on letters are relatively widespread on various types of inscription,Footnote 89 though pigments could evidently be derived from locally sourced ingredients if they produced the desired colour. This is confirmed by the presence of madder and realgar reds on the lettering of the Hunterian stones and the deeper and richer red of vermilion identified on letters on sculptures from Hadrian's Wall that were analysed during this project. The latter also presented some unexpected results, notably the application of blue to the names of dedicators and red to the remainder of the inscribed letters; this clearly warrants further investigation. The lettering of the Antonine sculptures appears to have been painted solely in red. Bold, red lettering would certainly have made these inscriptions easily legible. High lead in the A of AELIO on the Bridgeness stone indicates the presence of bright-red minium, which may have been used to embolden the emperor's name against a different red for the dedicators (Legion II); though it is equally possible that minium was used for all the lettering on this stone, as no other clear evidence for pigments was recovered from the inscribed letters.

A preference for shades of red pigment is further evidenced on iconographic features. Bright-red minium (red lead) is present on the chests, beard, head, thigh and cheek of captives on the Summerston relief sculpture and was probably employed in order to depict splashes of blood on warriors fresh from a battle with the Roman legions. This corresponds with similar features on the Bridgeness sculpture, where minium is evident on the shield of a fallen warrior as well as the decapitated neck of another. The colour remains visible in the latter area to this day, as does the red from iron oxide pigment applied to the rider's cloak and that of the individual on the far right of the sculpture (right panel). Intriguingly, minium is also present on the beak of the eagle on the right panel of the Summerston Farm sculpture; this perhaps symbolises Rome feasting off the blood of her captive enemies (fig. 8).

FIG. 8. Locations of high iron (red) and high lead (blue) on the Summerston Farm Distance Sculpture.

Yellow ochre is present on skin areas, such as the cheeks of the rider, soldier and fallen northern warrior on the Bridgeness sculpture, and potentially confirms the layering of colours to achieve realistic skin tones. The lustrous, golden-yellow of orpiment has been applied to adorn the dress of the winged goddess Victory, which is trimmed with lead white and possibly featured splashes of red blood from the nearby captives fresh from battle. This is in line with Victory's depiction on Pompeiian frescoes or the skirts of the goddess Roma and winged Victory on the Nicomedia relief (fig. 3) where colours are uniquely well preserved due the sculpture's placement in the interior of an imperial cult building.Footnote 90

It is important to acknowledge that the primary material focus of this research, the Antonine Wall Distance Sculptures, has presented significant challenges to its analysis using non-destructive techniques that are designed for use on ‘clean’ heritage materials that retain visible pigments. These challenges include the high fluorescence peaks emitted by the inherent properties of sandstone that mask genuine Raman peaks from pigments. This is compounded by the properties of many commonly used Roman pigments which make them problematic to identify with Raman, combined by their dilution and exposure to debilitating post-depositional processes. These include the harsh Scottish environmental conditions, including high rainfall, low temperatures, ground saturation and acidic soils, and cleaning by well-meaning museum staff striving to make the sculptured stones presentable to the viewing public. It is gratifying to conclude that, despite the inherent challenges, it has been possible to reconstruct – both physically and digitally – the colours that would originally have adorned these unique and exquisitely crafted objects (table 4).

TABLE 4 THE PALETTE OF COLOURS ON THE ANTONINE WALL DISTANCE STONES

Furthermore, it has been possible to confirm the restricted palette of reds and yellows that dominated the repertoire of the Roman artisans who worked on these stones, in the context of the occasional hints of blue, white and black on other examples from northern England. Despite the relatively lengthy lists of pigments catalogued by Pliny (book 35) and Vitruvius (book 7), the use of the more exotic, expensive and less readily available pigments defined by Pliny (HN 35.12) as ‘florid’ was largely restricted to élites, with the notable exception of cinnabar, which is known to have been mixed with other minerals. Thus the use of pigments categorised by Pliny (HN 35.12) as ‘austere’, which were much more commonly available and accessible across the Empire, including red and yellow ochres, carbon black, terres vertes, chalk-based whites and mixtures of these colours,Footnote 91 is, therefore, unsurprising. The principal palette of colours evidenced on the sculpted stones from the Antonine Wall and other northern contexts can clearly be placed into Pliny's ‘austere’ category and can be sourced locally. The others, including orpiment and realgar, are rarely used and not locally available. These can be categorised as ‘florid’ and imported from other parts of the Empire.

The early decision to incorporate additional inscribed stones and statuary from northern England into this work for comparative purposes has proven invaluable, since they are known to have remained devoid of any intervention since the time of their discovery. Thus, extant pigments have not degenerated and provide useful datasets for comparison against the Scottish evidence. Here too, reds and yellows are the predominant colours, though with a broader palette.

Working closely with a digital artist, Lars Hummelshoj, it has been possible to reconstruct digitally one iconic scene from the Bridgeness sculpture by matching these authentic colours with Pantone codes and taking account of experimental work that has been undertaken to determine how the original pigments would have worked with the sandstone (fig. 9). The various reds on the cloak and tunic of the rider and the bright minium red depicting blood on the fallen northern warrior's headless body and neck are clearly distinguishable. Slight artistic licence has been taken with the colour of the cuirass, which has been depicted as bronze, like the representations of the Praetorian Guard on a relief in the Musée du LouvreFootnote 92 and those recovered from a shipwreck near Cuea del Jarro dating from the first to the third centuryFootnote 93 or the striking digital reconstruction of a cuirass from the Athenian Acropolis.Footnote 94 The bronze terminals of the rider's pteryges (the defensive skirt of leather strips worn by Roman soldiers over their tunics) have been similarly extrapolated from other evidence,Footnote 95 such as a life-size sandstone representation of Mars in the Yorkshire Museum.

FIG. 9. Digital reconstruction of the Bridgeness Distance Sculpture. (Reconstruction by Lars Hummelshoj)

The result is a strikingly realistic image of warfare that must surely have been a powerful propaganda tool, serving simultaneously to strike fear into the hearts of the indigenous population while also evoking a sense of dominance for the military audience.

More sensitive technologies currently under development for use by the heritage sector should identify with better precision spots for analysis by employing lasers sufficiently sensitive to detect pigments that may have been subjected to dilution and erosion over time. The author is working with academics of the Particle Physics Experiment Team at the University of Glasgow to develop and refine equipment combining Raman spectroscopy and X-ray fluorescence with medipix technologies in a portable format that can be tailored to this task. This bespoke equipment will ensure consistency in the spots analysed by both pXRF and Raman. It also offers the very attractive potential to undertake systematic mapping and X-ray imagery of sculptures and artwork to determine with precision the locations of surviving pigments and to identify paint layering. It is hoped that the technology and associated software can be used to build a robust methodology and comprehensive data resource for use by other researchers across a variety of disciplines.

This research builds on previous pXRF work sourcing production centres for Samian potteryFootnote 96 to demonstrate that non-destructive techniques can be applied successfully to a previously unexplored field of study in order to identify and facilitate the reconstruction and conservation of pigments applied to sandstone statuary in antiquity. The work stands as a testament to the benefits of integrated and multidisciplinary approaches to materials science. It opens exciting and innovative avenues for future exploration into other strands of material culture studies, including analysis of stone statuary from other epochs, painted terracotta statues, painted wooden panels, frescoes, textiles, organic materials, textiles and stained glass. If combined with emerging technologies integrating pXRF, Raman and imagery (X-ray and multi spectral), the potential for non-destructive in-situ analysis of archaeological materials is exciting and, possibly, limitless.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Most sincere thanks are due to Historic Environment Scotland for its generosity in part-funding this research, particularly to Rebecca Jones, Patricia Weeks and Lisa Brown, and to Richard Jones (University of Glasgow) for assisting with the analysis and reports. I am immensely grateful to Professors Lawrence Keppie and David Breeze for their guidance and invaluable comments on an earlier version of this paper and to Lars Hummelshoj for digitally reconstructing a scene from the Bridgeness sculpture.