Introduction

Findings from community-based studies indicate that females develop internalizing symptoms and disorders (e.g. depression, anxiety disorders, eating disorders) at higher rates than males, a gender difference that emerges during early adolescence and persists through midlife (e.g. Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Williams, McGee and Silva1987; Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Cohen, Kasen, Velez, Hartmark, Johnson, Rojas, Brook and Streuning1993; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, McGonagle, Swartz, Blazer and Nelson1993; Lewinsohn et al. Reference Lewinsohn, Hops, Roberts, Seeley and Andrews1993; Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, Reference Nolen-Hoeksema and Girgus1994; Weissman et al. Reference Weissman, Bland, Canino, Faravelli, Greenwald, Hwu, Joyce, Karam, Lee, Lellouch, Lépine, Newman, Rubio-Stipec, Wells, Wickramaratne, Wittchen and Yeh1996; Hankin et al. Reference Hankin, Abramson, Moffitt, Silva, McGee and Angell1998). In a parallel body of research, there is growing interest in gender differences in rates and effects of childhood victimization. Clearly, rates of exposure to childhood victimization vary by type of victimization and age of respondents; as reported by adults, for example, rates of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) are higher in females than males whereas rates of childhood physical abuse (CPA) are higher in males than females (e.g. Gorey & Leslie, Reference Gorey and Leslie1997; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Davis and Kendler1997; MacMillan et al. Reference MacMillan, Fleming, Trocme, Boyle, Wong, Racine, Beardslee and Offord1997; Molnar et al. Reference Molnar, Buka and Kessler2001b). Less attention, however, has been given to gender differences in the effects of childhood victimization. Apart from differential exposure to victimization by gender, if the effects of victimization vary by gender, such that females are more prone than males to develop psychopathology after being victimized, then this could contribute to gender differences in prevalence and incidence rates of psychiatric illnesses. This is the topic of the current review.

Cutler & Nolen-Hoeksema (Reference Cutler and Nolen-Hoeksema1991) first proposed that gender differences in the effects of CSA might contribute to females' greater vulnerability to depression. Based on their review of rates of exposure to CSA by gender and rates of depression among victims of CSA by gender, the authors estimated that the female-to-male ratio in prevalence rates of depression is reduced by approximately 9–35% when rates of CSA-related depression are taken out. This seminal report was based primarily on clinical and legal samples, and was limited to only one type of childhood victimization experience (CSA) and one type of psychiatric outcome (depression).

Among the meta-analyses and literature reviews on this topic that have been published since 1991 (e.g. Kendall-Tackett et al. Reference Kendall-Tackett, Williams and Finkelhor1993; Jumper, Reference Jumper1995; Neumann et al. Reference Neumann, Houskamp, Pollock and Briere1996; Rind & Tromovitch, Reference Rind and Tromovitch1997; Rind et al. Reference Rind, Tromovitch and Bauserman1998; Weiss et al. Reference Weiss, Longhurst and Mazure1999; Putnam, Reference Putnam2003), four warrant mentioning here because they explore gender as a potential moderator of the association between childhood victimization and psychological outcomes. Jumper (Reference Jumper1995) evaluated the relationship between CSA and psychological outcomes in both community- and non-community-based adult samples. Separate meta-analyses were performed for each of the outcome categories measured (i.e. depression, psychological symptomatology, and self-esteem). Studies were partitioned by study characteristics (e.g. sample source, subject gender) and these characteristics were tested to determine whether they accounted for significant differences in effect size estimates within each of the three outcome categories measured. Gender was found to moderate the effect of CSA on self-esteem but not on depression or psychological symptomatology. It should be noted that Rind et al. (Reference Rind, Tromovitch and Bauserman1998) recomputed the effect sizes using only community-based samples from Jumper's (Reference Jumper1995) original meta-analysis. The authors found higher effects for psychological symptomatology in females (r=0.22) than males (r=0.11), but did not test whether these two correlations were significantly different. They concluded that these results suggest a gender difference. Only four studies in this analysis included males.

In a meta-analysis by Rind & Tromovitch (Reference Rind and Tromovitch1997), the association between CSA and adjustment problems was examined using community samples from the USA, Canada, the UK and Spain. Mean effect sizes were computed separately by gender, with similar effects found in females (r=0.10) and males (r=0.07). The two correlations were tested and found not to be significantly different. For self-reported negative effects, significantly more females (68%) than males (42%) reported the presence of some type of negative effect. The magnitude of this gender difference was found to be small to medium (r=0.23); however, only three studies in this analysis included males.

Rind et al. (Reference Rind, Tromovitch and Bauserman1998) examined the relationship between CSA and psychological adjustment outcomes (e.g. alcohol problems, interpersonal sensitivity) in samples recruited from college and university student populations. Effect sizes were computed for the association between CSA and psychological outcomes, and for the magnitude of the relationship between several moderating variables (e.g. gender, level of contact) and psychological outcomes. Significant interactions were found between gender and two moderating aspects of the CSA experience, namely level of contact (i.e. psychological outcomes were significantly stronger for males than females when CSA was unwanted) and timing of reaction (i.e. negative reactions to CSA were significantly greater for females than males across each category of reaction timing that was measured: immediate, current, and lasting).

Finally, Paolucci et al. (Reference Paolucci, Genuis and Violato2001) examined the relationship between CSA and psychological outcomes [e.g. symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), poor academic performance] in primarily non-community-based samples. Average effect sizes were calculated for all dependent variables across studies. Potential mediating variables (e.g. gender) were examined using a series of analyses of variance (ANOVAs). None of the mediating variables were found to be statistically significant. The authors did not test for moderating role of gender (i.e. no test of interactions).

In sum, we have identified several literature reviews that have specifically explored the role of gender in the effects of childhood victimization. In general, these reviews provide mixed support for gender moderating the effects of victimization on outcomes. The conclusions that can be drawn from these reviews are limited by the inclusion of non-community-based samples (Jumper, Reference Jumper1995; Rind et al. Reference Rind, Tromovitch and Bauserman1998; Paolucci et al. Reference Paolucci, Genuis and Violato2001), inadequate numbers of males in samples (Jumper, Reference Jumper1995; Rind & Tromovitch, Reference Rind and Tromovitch1997; Rind et al. Reference Rind, Tromovitch and Bauserman1998 – recalculation of effect sizes from Jumper, Reference Jumper1995), and no specific test for gender differences (Rind et al. Reference Rind, Tromovitch and Bauserman1998 – recalculated; Paolucci et al. Reference Paolucci, Genuis and Violato2001). Additionally, a number of these reviews measure non-psychiatric outcomes alongside psychiatric outcomes (Rind & Tromovitch, Reference Rind and Tromovitch1997; Rind et al. Reference Rind, Tromovitch and Bauserman1998; Paolucci et al. Reference Paolucci, Genuis and Violato2001), and all focus exclusively on CSA (Jumper, Reference Jumper1995; Rind & Tromovitch, Reference Rind and Tromovitch1997; Rind et al. Reference Rind, Tromovitch and Bauserman1998; Paolucci et al. Reference Paolucci, Genuis and Violato2001).

The current paper aims to address these limitations by reviewing studies that used only community-based samples, included representative numbers of males in their samples, specifically tested for gender differences, used well-defined psychiatric outcomes, and examined a range of childhood victimization experiences. In our review, we have defined childhood victimization as abuse (i.e. sexual, physical, emotional/psychological) by adults or peers that occurred before 18 years of age. Victimization experiences include overt forms (e.g. physical or sexual assault, threats of assault, bullying), as well as subtle and relational forms, observed in studies of peer victimization (e.g. manipulation, spreading rumors, intentional social exclusion).

Method

Relevant studies were identified through computer-generated searches on PsycINFO and Medline databases (1996–2006) using the following key words: child abuse, mental disorders, and human sex differences (or ‘sex factors’ for Medline). These searches were repeated with closely related terms substituting for the child abuse term (i.e. physical abuse, sexual abuse, victimization, peer victimization, relational victimization, bullying) and for the mental disorders term (i.e. psychopathology, emotional adjustment, psychological adjustment). Literature was limited to empirical studies published in English between 1996 and 2006. References cited in studies identified through computer-generated searches were also reviewed systematically. The results generated from these searches were combined and duplicates removed, producing an initial sample of 763 published research articles.

To be included in the present review, studies were required to satisfy three criteria. First, community-based samples were necessary. The majority of studies on childhood victimization excluded from this review were disqualified because of the use of samples drawn from referral sources (e.g. psychiatric clinics, protective service agencies) that are not representative of the general population. Likewise, other non-community-based recruitment sources (e.g. police, hospitals, child welfare records, colleges/universities, military) were excluded because they introduce sampling and selection biases that limit the validity of the findings (e.g. a history of child abuse has been shown to increase the likelihood of dropping out of college; Duncan, Reference Duncan2000). Our second criterion required representative numbers of male and female participants. Many studies, particularly those examining CSA, comprise exclusively female samples or samples with a small number of males and were therefore excluded. Third, studies were required to specifically test for gender differences, by inclusion of a gender by victimization interaction term, or by calculation of the significance of the difference between measures of association (e.g. odds ratios) for males versus females. If a formal test for gender differences was not performed but sufficient data were provided from which gender differences could be evaluated from confidence intervals surrounding reported measures of association, we applied an algorithm comparing the confidence intervals in males to those in females to determine if these intervals were non-overlapping.

Abstracts were evaluated against our inclusion criteria and were either eliminated (n=651) or judged to be of probable fit (n=112). The latter were carefully and independently reviewed by at least two of the three authors to determine whether they met inclusion requirements. All disagreements were resolved by discussion. This method resulted in 30 original empirical investigations.

Results

Adult community samples

Nine studies with adult samples were identified that formally tested for gender differences in the effects of childhood victimization on psychiatric outcomes. The findings are summarized in Table 1. Three additional studies with adult samples were identified: two of these reported finding multiple significant gender by victimization interactions but did not specify which of the tested interactions were significant (Molnar et al. Reference Molnar, Berkman and Buka2001a, Reference Molnar, Buka and Kesslerb), and one study did not formally test for gender differences but provided sufficient data from which these differences could be evaluated from confidence intervals surrounding reported measures of association (Dinwiddie et al. Reference Dinwiddie, Heath, Dunne, Bucholz, Madden, Slutske, Bierut, Statham and Martin2000). For these additional studies, we report the measures of association separately by gender, and examine whether the corresponding confidence intervals are non-overlapping. The findings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1. Adult samples: gender differences formally tested

MDD, Major depressive disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; CD, conduct disorder; CSA, childhood sexual abuse; CPA, childhood physical abuse; OR, odds ratio; CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table 2. Adult samples: gender differences evaluated from confidence intervals surrounding reported measures of association

MDD, Major depressive disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; CSA, childhood sexual abuse; OR, odds ratio; CI, 95% confidence interval.

Sexual victimization

Of the studies that formally tested for gender differences in the effects of CSA, three found significant differences. First, using data from the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey (n=8116, ages 15–64 years), Chartier et al. (Reference Chartier, Walker and Stein2001) found a significant gender by CSA interaction whereby severe CSA was associated with higher risk for social phobia (over the past year) in females than males. Second, again using data from the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey (n=7016, ages 15–64 years), MacMillan et al. (Reference MacMillan, Fleming, Streiner, Lin, Boyle, Jamieson, Duku, Walsh, Wong and Beardslee2001) found that the elevated risk for anxiety disorders associated with CSA was significantly higher (significant interaction term) among females than males. Two additional near-significant gender by CSA interactions warrant mention; namely, the risks for major depression and for antisocial behaviors associated with CSA were higher in females compared to males. Third, based on data from twin pairs (n=2708 pairs, ages 23–36 years), Knopik et al. (Reference Knopik, Heath, Madden, Bucholz, Slutske, Nelson, Statham, Whitfield and Martin2004) found a significant gender by CSA interaction whereby CSA was associated with higher risk for alcohol risk in females than males.

Two published studies using data collected from the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS, n=5877) reported finding multiple significant gender by victimization interactions but lack specificity with regard to which of the tested gender interactions were significant. First, Molnar et al. (Reference Molnar, Berkman and Buka2001a) examined the risk for suicidal behavior associated with a history of CSA, and tested whether this risk was mediated by a history of lifetime psychiatric disorders. Based on the odds ratios (ORs) reported (without knowing which gender by victimization interactions are significant), a history of CSA appears to be associated with higher risk for suicidal behavior in males than females (Molnar et al. Reference Molnar, Berkman and Buka2001a). Second, Molnar et al. (Reference Molnar, Buka and Kessler2001b) examined the risk for a range of psychiatric conditions associated with a history of CSA. Based on reported ORs, CSA appears to be associated with higher risk for dysthymia, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic attack, panic disorder, PTSD, simple phobia, drug problems, and severe drug dependence in females than males, whereas in males, CSA is associated with risk equal to, or greater than, females for depression, social phobia, alcohol problems and dependence, severe alcohol dependence, drug dependence, and the ‘any disorder’ category.

Finally, Dinwiddie et al. (Reference Dinwiddie, Heath, Dunne, Bucholz, Madden, Slutske, Bierut, Statham and Martin2000) examined the relationship between CSA and a range of lifetime psychopathology (including alcohol abuse/dependence, major depression, anxiety disorders, conduct disorder, and suicidal ideation/attempts) using a twin-study method. The authors did not test for gender interactions or gender differences in ORs. Using the criterion of ORs with non-overlapping confidence intervals, no gender differences were found.

Physical victimization

Of the studies that formally tested gender differences in this category, one found significant gender differences. Specifically, MacMillan et al. (Reference MacMillan, Fleming, Streiner, Lin, Boyle, Jamieson, Duku, Walsh, Wong and Beardslee2001) found a significant gender interaction whereby CPA was associated with higher risk for major depression, alcohol abuse/dependence, illicit drug abuse/dependence, and antisocial behaviors in females than males.

Child and adolescent community samples

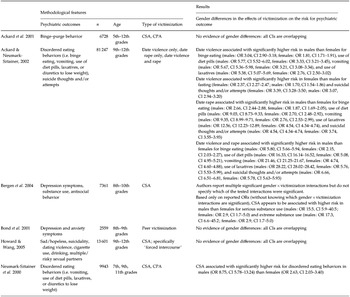

Twelve studies with child and adolescent samples were identified that formally tested for gender differences in the effects of childhood victimization on psychiatric outcomes. The findings from these studies are summarized in Table 3. Six additional studies were identified that did not formally test for gender differences but provided sufficient data from which gender differences could be evaluated from confidence intervals surrounding reported measures of association. The findings from these studies are summarized in Table 4.

Table 3. Child and adolescent samples: gender differences formally tested

PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; ADHD, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; CD, conduct disorder; CSA, childhood sexual abuse; CPA, childhood physical abuse; OR, odds ratio; CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table 4. Child and adolescent samples: gender differences evaluated from confidence intervals surrounding reported measures of association

CSA, Childhood sexual abuse; CPA, childhood physical abuse; OR, odds ratio; CI, 95% confidence interval.

Sexual victimization

Of the studies that formally tested for gender differences in the effects of CSA, three found significant differences. First, a study by Bergen et al. (Reference Bergen, Martin, Richardson, Allison and Roeger2003) using a sample of young adolescents (n=2596, grades 8–10) found that CSA was associated with significantly higher risk for hopelessness (significant interaction term) in males than females, and that CSA was independently and directly associated with suicide attempts in females but not males (although the authors noted that the latter gender difference may be a reflection of a lack of power due to a small number of males reporting a history of CSA).

Second, two published reports using a single sample of adolescents (n=1490, ages 12–19 years) found the following significant gender interactions: CSA was associated with higher risk for emotional problems (e.g. anxiety, depressed mood), suicidal thoughts/behaviors, and for reporting more categories of mental health problems in males than females (Garnefski & Diekstra, Reference Garnefski and Diekstra1997). CSA was also associated with significantly higher risk (significant interaction term) for behavioral problems (defined as alcohol/drug use, aggressive/criminal behavior, and truancy) and suicidal thoughts/attempts in males than females (Garnefski & Arends, Reference Garnefski and Arends1998). Because the two reports used the same sample, we have counted these as one study. Finally, a study by Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Bergen, Richardson, Roeger and Allison2004) (n=2485, 8th–10th grades) found a significant gender interaction whereby CSA was associated with higher risk for suicidal plans and attempts in males than females.

Three additional studies provided sufficient information from which gender differences in the effects of CSA could be evaluated from confidence intervals surrounding reported measures of association. First, Ackard & Neumark-Sztainer (Reference Ackard and Neumark-Sztainer2002) found significant gender differences in the effects of date violence and/or rape on risk for eating disorder symptoms and suicidality among 81247 adolescents (9th–12th grades). Specifically, date violence was associated with significantly higher risk in males than females for binge eating, use of diet pills, vomiting, and use of laxatives, and associated with significantly higher risk in females than males for fasting and suicidal thoughts and/or attempts. Similarly, date rape was associated with significantly higher risk in males than females for binge eating, use of diet pills, vomiting, and use of laxatives, and with significantly higher risk for suicidal thoughts and/or attempts in males than females. Finally, the experience of both date violence and rape was associated with significantly higher risk for binge eating, use of diet pills, vomiting, use of laxatives, and suicidal thoughts and/or attempts in males than females.

Second, Bergen et al. (Reference Bergen, Martin, Richardson, Allison and Roeger2004) examined the risk for depression, substance use, and antisocial behavior among adolescents (n=7361, 8th–10th grades). Based only on reported ORs (without knowing which gender by victimization interactions are significant), CSA appears to be associated with higher risk for serious and extreme substance use in males than females. Third, Neumark-Sztainer et al. (Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story, Hannan, Beuhring and Resnick2000) found that CSA was associated with significantly higher risk (ORs with non-overlapping confidence intervals) for disordered eating behaviors in males than females (n=9943, 7th, 9th and 11th grades).

Physical victimization

Of the studies that formally tested gender differences in this category, two studies found evidence for significant differences in the risk for psychiatric outcomes. First, in a prospective study of children (n=1433, ages 10–16 years), Boney-McCoy & Finkelhor (Reference Boney-McCoy and Finkelhor1996) examined the effects of the following six forms of assault on the risk for PTSD and depression symptoms at the 15-month follow-up: aggravated assault (physical assault involving use of weapon or injury to victim) by a non-family member; simple assault (without a weapon and without injury) by a non-family member; physical assault by a parent; physical assault by a family member other than a parent; sexual assault; and violent but not sexual assault to the genitals. Significant gender interactions were found in the risk for PTSD symptoms. Specifically, females who had experienced ‘any victimization’ or aggravated assault demonstrated significantly higher risk for PTSD symptoms than males, whereas simple assault was associated with significantly higher risk for PTSD symptoms in males than females. A second prospective study by Briggs-Gowan et al. (Reference Briggs-Gowan, Owens, Schwab-Stone, Leventhal, Leaf and Horowitz2003) investigated the contribution of CPA to the persistence of psychiatric disorders among children (n=996, ages 5–11 years) recruited from a random sample of 23 pediatric practices. Findings indicated a significant gender interaction whereby CPA was associated with higher risk for disorder persistence at the 1-year follow-up in males than females. Two additional studies (Neumark-Sztainer et al. Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story, Hannan, Beuhring and Resnick2000; Ackard et al. Reference Ackard, Neumark-Sztainer, Hannan, French and Story2001) provided sufficient information from which gender differences could be evaluated from confidence intervals surrounding reported ORs; neither study found significant differences.

Peer victimization

Of the studies that formally tested for gender differences in this category, four found evidence for significant differences. Evidence that victimized males fare worse than victimized females is as follows. First, among high-school students (n=566), overt victimization by peers was associated with significantly higher risk (significant interaction term) for depression symptoms in males than females (Prinstein et al. Reference Prinstein, Boergers and Vernberg2001). Second, Schwartz et al. (Reference Schwartz, McFayden-Ketchum, Dodge, Pettit and Bates1998) prospectively investigated the effect of peer victimization on the risk for internalizing, externalizing, attention, and social problems in school-age children (n=330, 3rd–6th grades). A significant gender interaction was found whereby peer victimization was associated with more attention problems at the 2-year follow-up in males than females.

One study demonstrated that females fare worse than males; in a prospective study of 4th–6th-grade children (n=471), Khatri et al. (Reference Khatri, Kupersmidt and Patterson2000) found that peer victimization was associated with significantly higher risk (significant interaction term) for delinquency at the 1-year follow-up in females than males. The remaining study by Sullivan et al. (Reference Sullivan, Farrell and Kliewer2006) (n=276, 8th graders) also found significant gender interactions: physical peer victimization was associated with higher risk for delinquency, alcohol use, and advanced alcohol use in males than females, whereas relational peer victimization was associated with higher risk for marijuana use in females but not males. An additional study (Bond et al. Reference Bond, Carlin, Thomas, Rubin and Patton2001) provided sufficient information from which gender differences in the effects of peer victimization could be evaluated from confidence intervals surrounding reported measures of association; no gender differences were found.

Discussion

The results do not yield a simple answer to the question of whether childhood victimization has differential effects by gender on psychiatric outcome. Instead, our findings suggest interesting gender differences in the effects of childhood victimization on psychiatric outcome depending on the age of participants at the time of assessment (i.e. youth versus adult). In general, adult samples show either that victimization is associated with greater risk in females than males (n=4) or that there are no differences by gender (n=7). Only three studies found increased risk in male adults, and one of these studies also showed increased risk in female adults depending on measured outcomes (i.e. victimization was associated with greater risk for social phobia and some substance problems in males, and dysthymia, anxiety disorders, PTSD, and some substance problems in females). By contrast, studies among youth indicate either that there are no gender differences (n=7) or that males tend to have worse outcomes than females (n=12). Although five youth studies demonstrate worse outcomes for females compared to males, four of these also reported worse outcomes in males depending on the type of victimization or outcomes assessed.

With respect to outcome, when gender differences were reported, they were distributed across both internalizing and externalizing categories for both genders. However, we again find evidence for interesting time-of-sampling differences. Within the adult studies that assessed internalizing outcomes, there was a trend for females to fare worse than males, whereas males tended to have worse outcomes than females within youth studies that assessed externalizing outcomes.

It is not clear why the findings are different for youth samples relative to adult samples. In studies with youth samples, the temporal proximity of the victimization experience to measured outcomes may play a role, whereas in studies with adult samples, there may be ‘forgetting’ of past victimization experiences. In the latter case, increased temporal distance from the event would be expected to attenuate the associations observed in youth. As has been noted previously in the literature, reliance on retrospective designs in studies of the psychological impact of childhood victimization poses serious concerns; namely, studies with adults have shown that as many as 38% of individuals with substantiated CSA histories do not recall the abuse accurately (e.g. Williams, Reference Williams1994; Widom & Morris, Reference Widom and Morris1997). This explanation, however, would not account for the gender disparity between youth and adult studies unless there are also gender differences in the effect of time on memory for victimization experiences. There is evidence to suggest that women exhibit better biographical memory for emotional events from childhood (both positive and negative) than do men (Davis, Reference Davis1999). However, to our knowledge, there is no evidence to suggest that such a gender difference is specifically observed in memory for victimization in childhood.

Another possible explanation is related to course of illness. When psychiatric outcomes are measured in closer temporal proximity to childhood victimization, rates of psychiatric symptoms and disorders may be higher, and in some cases may dissipate over time. Thus, among adult samples, it is only those symptoms and disorders that persist into adulthood (or have adult onset) that are being measured. The effects of childhood victimization on psychiatric outcome may therefore be different in symptoms and disorders that are short term relative to those that are long term or have delayed onset. This explanation would not account for the gender disparity between youth and adult samples unless there are also gender differences in the course of illness of common psychiatric conditions, with females having a disproportionate number of longer illness episodes, or greater frequency of delayed onset. To our knowledge, there is no evidence to suggest this.

Several limitations should be noted. First, there may be a gender disparity in the general severity of childhood victimization experiences, such that females may experience more serious forms of victimization than males (e.g. more prolonged victimization, more likely to know the perpetrator than males). However, studies that test for statistical interactions between gender and victimization afford the opportunity to examine gender differences in the effects of victimization at any given level of measured victimization. It may be that there are unmeasured gender differences in levels of victimization that are more nuanced. These gender differences would be missed and could represent a confounding variable. It could appear that psychiatric outcomes are worse in females, for example, at a particular level of victimization, but in reality the levels are not discriminating enough to capture differences in severity by gender. Of interest, Pimlott-Kubiak & Cortina (Reference Pimlott-Kubiak and Cortina2003) investigated whether psychiatric outcomes varied by gender across a range of victimization experiences in a sample of 16 000 adults. The researchers standardized levels of victimization across gender, and no differential effects by gender on psychiatric outcomes were found.

Another potential limitation of the present review concerns differential rates of childhood victimization by gender. Specifically, if the rates of childhood victimization are disproportionately higher in females compared to males, then gender differences in psychiatric outcomes could be attributable to these differential rates by gender. Studies that test for gender differences in the effects of childhood victimization on psychiatric outcomes using a gender by victimization interaction term afford the opportunity to examine gender differences in the effect of victimization (by comparing slopes of the regression lines) despite gender differences in rates of different types of victimization.

Furthermore, there is some evidence to suggest that differential rates of exposure by gender to sexual victimization do not account for the elevated rates of internalizing disorders observed in females compared to males. To determine whether gender differences in depression and anxiety symptoms could be attributed to a history of CSA in a sample of youth (n=1053, ages 16–18 or 18–21 years), Fergusson et al. (Reference Fergusson, Swain-Campbell and Horwood2002) controlled for history of CSA in analyses, hypothesizing that this would significantly reduce the association between gender and depression and anxiety. They found that a history of CSA accounted for a small proportion of the gender difference in rates of depression and anxiety. Specifically, the OR for depression was reduced from 2.5 [confidence interval (CI) 1.9–3.1] to 1.9 (CI 1.4–2.3), p=0.03, and the OR for anxiety from 2.3 (CI 1.7–3.1) to 1.8 (CI 1.3–2.4), p=0.08.

A general methodological limitation of the studies we reviewed concerns variability in definitions of childhood victimization. The child abuse literature is plagued by inconsistent definitions of victimization, in some cases too variable to allow comparison across studies. For example, individuals who are identified as having experienced CSA may have also experienced varying degrees of CPA, psychological abuse, or neglect that are either not measured or not reported. Similarly, victimization experiences may vary widely in severity, frequency, or duration, or in the relationship of the perpetrator to the victim. Studies often fail to measure or report characteristics of victimization experiences. Variability in definitions of childhood victimization, however, would only alter the results of this review if inconsistencies differed by gender. We are not aware of evidence for this.

Another general methodological limitation of the literature we reviewed is a paucity of longitudinal studies. We identified only five prospective studies. When examined separately, the results from prospective studies are similar to those found across all studies reviewed. Specifically, four studies report significant gender by victimization interactions: two demonstrate greater risk in males (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, McFayden-Ketchum, Dodge, Pettit and Bates1998; Briggs-Gowan et al. Reference Briggs-Gowan, Owens, Schwab-Stone, Leventhal, Leaf and Horowitz2003), one demonstrates greater risk in females (Khatri et al. Reference Khatri, Kupersmidt and Patterson2000), and the remaining study shows greater risk in both genders, depending on the type of victimization assessed (Boney-McCoy & Finkelhor, Reference Boney-McCoy and Finkelhor1996). As all four studies were with youth, time-of-sampling differences cannot be examined. With regard to psychiatric outcomes, these were distributed across both internalizing and externalizing categories for both genders.

Studies examining psychiatric outcomes of trauma have been excluded from the present review because trauma is a term that encompasses a range of severely stressful experiences in addition to childhood victimization (e.g. military combat; mugging; serious car accident; fire; flood; life-threatening illness; witnessing acts of violence, death or serious injury; discovering a corpse). Unless the role of childhood victimization is explicitly examined by the researchers, the range of events assessed by the term trauma makes it difficult to tease apart whether the gender differences observed in psychiatric outcomes of trauma are attributable to exposure to victimization in childhood or to other stressful events measured.

It is worth noting, however, that a number of community-based studies provide evidence that females exposed to trauma exhibit a higher risk of developing PTSD than trauma-exposed males (e.g. Norris, Reference Norris1992; Breslau et al. Reference Breslau, Davis, Andreski and Peterson1997, Reference Breslau, Chilcoat, Kessler, Peterson and Lucia1999), even after controlling for type of trauma or ‘most upsetting’ trauma (e.g. Norris, Reference Norris1992; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes and Nelson1995; Breslau et al. Reference Breslau, Davis, Andreski and Peterson1997). There is evidence to suggest that these gender differences in PTSD may be largely due to the effects of ‘assaultive’ forms of trauma (e.g. threat with weapon, rape; Breslau et al. Reference Breslau, Chilcoat, Kessler, Peterson and Lucia1999) or to violent crime, for which exposed females exhibited twice the rate of PTSD of exposed males (Norris, Reference Norris1992). Tolin & Foa (Reference Tolin and Foa2006), in their recent meta-analysis of 40 studies using non-clinical samples, examined the possibility that higher rates of PTSD among females might be attributable to higher lifetime rates of sexual victimization among females compared to males, but found no significant gender differences in risk for PTSD among individuals with a history sexual victimization.

In summary, our findings challenge the long-standing supposition that victimization experiences are associated with differentially poorer psychiatric outcomes in females relative to males. Taken together, the findings from the 30 studies considered in this review indicate that the evidence for gender differences in the effects of childhood victimization is neither simple nor compelling. Many studies find no evidence for gender differences, and when these differences are found, they vary by the age of participants at the time of assessment (i.e. youth versus adult). Thus, gender differences in prevalence rates of internalizing disorders, such as depression, do not appear to be attributable to differential effects of childhood victimization. Our findings underscore the need for elucidating more precise gender- and age-specific paths for psychiatric outcomes. We suspect that descriptions of gender differences that account for differences in context (e.g. frequency, duration, severity, relationship of perpetrator to victim) and significance of victimization experiences may reveal more meaningful differences related to psychiatric outcomes. Ultimately, including gender-related issues in primary and secondary prevention efforts will require more attention to exactly how and why child victimization leads to psychiatric outcomes in some individuals but not in others. Proper attention to these subtle yet important concerns is necessary to link primary and secondary prevention efforts related to downstream psychiatric sequelae of childhood victimization.

Declaration of Interest

None.