In Cappadocia, a region in central Turkey renowned for its idiosyncratic volcanic landscape and rock-cut architecture, the majority of surviving structures carved out of the soft tuff stone date back to the Byzantine period. Hundreds of the rock-cut churches found here feature well-established Byzantine ecclesiastical plan types adapted into this unique natural setting, but usually on a smaller scale.Footnote 1 By contrast, several large rock-cut complexes, generally identified as tenth to eleventh-century mansions of the local aristocracy, are among the rare examples of Byzantine secular architecture: not much has survived elsewhere in the empire.Footnote 2 Although they generally have single-storey interiors, these rock-cut mansions are decorated with engraved façades that often evoke a multi-storey architectural perception (Fig. 1).Footnote 3

Fig. 1: Açıksaray, Area 1 (background) and Area 2 (foreground) (photo: Aykut Fenerci)

There are more than forty such mansions spread out across the volcanic valleys of Cappadocia, either as isolated estates or as groups forming settlements such as at Çanlı Kilise, Selime-Yaprakhisar, and Açıksaray (Fig. 2). Since many of these are organized around naturally or artificially formed three-sided (U-shaped) open courtyards, they have come to be referred to in the literature as courtyard complexes. Echoing the over-generalized and largely unfounded identity of Cappadocia as a supposedly ‘monastic centre’, these complexes too were initially labelled as monasteries. It was only recently that they began to be reconsidered to be mansions belonging to the elite, which is now widely accepted.Footnote 4

Fig. 2: Map of Cappadocia, distribution of courtyard complexes (drawing: author)

The courtyard complexes usually feature a central core, obviously used for reception purposes and often occupied by two halls: a vestibule and the main hall, these perpendicular to each other and forming an inverted-T plan. Service spaces, such as kitchens, stables and occasionally a humble chapel secondary to the halls, were also carved into the rock around the courtyard (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, the most apparent common qualities of the courtyard complexes are their two to four-storied rock-cut façades decorated to imitate built architecture (Figs 4–5).Footnote 5 Ironically, while these façades carved onto the living rock have survived, their potential prototypes among built architecture have been almost entirely lost.Footnote 6 It is the absence of built structures of their kind and their uniqueness among other rock-cut structures that make the façades of courtyard complexes stand out. Comparison of extant façades demonstrates that the symmetrically organized monumental façades of courtyard complexes differ significantly from the often simple and haphazardly carved façades of the region's religious establishments, such as hermitages, free-standing churches, and probable monastic complexes.Footnote 7 The rest of the Cappadocian medieval settlements usually evolved organically without any identifiable layout, and they often lack façade decoration altogether.

Fig. 3: Açıksaray, Area 5, plan (survey/drawing: author and Aykut Fenerci)

Fig. 4: Açıksaray, Area 5, the main façade (photo: Aykut Fenerci)

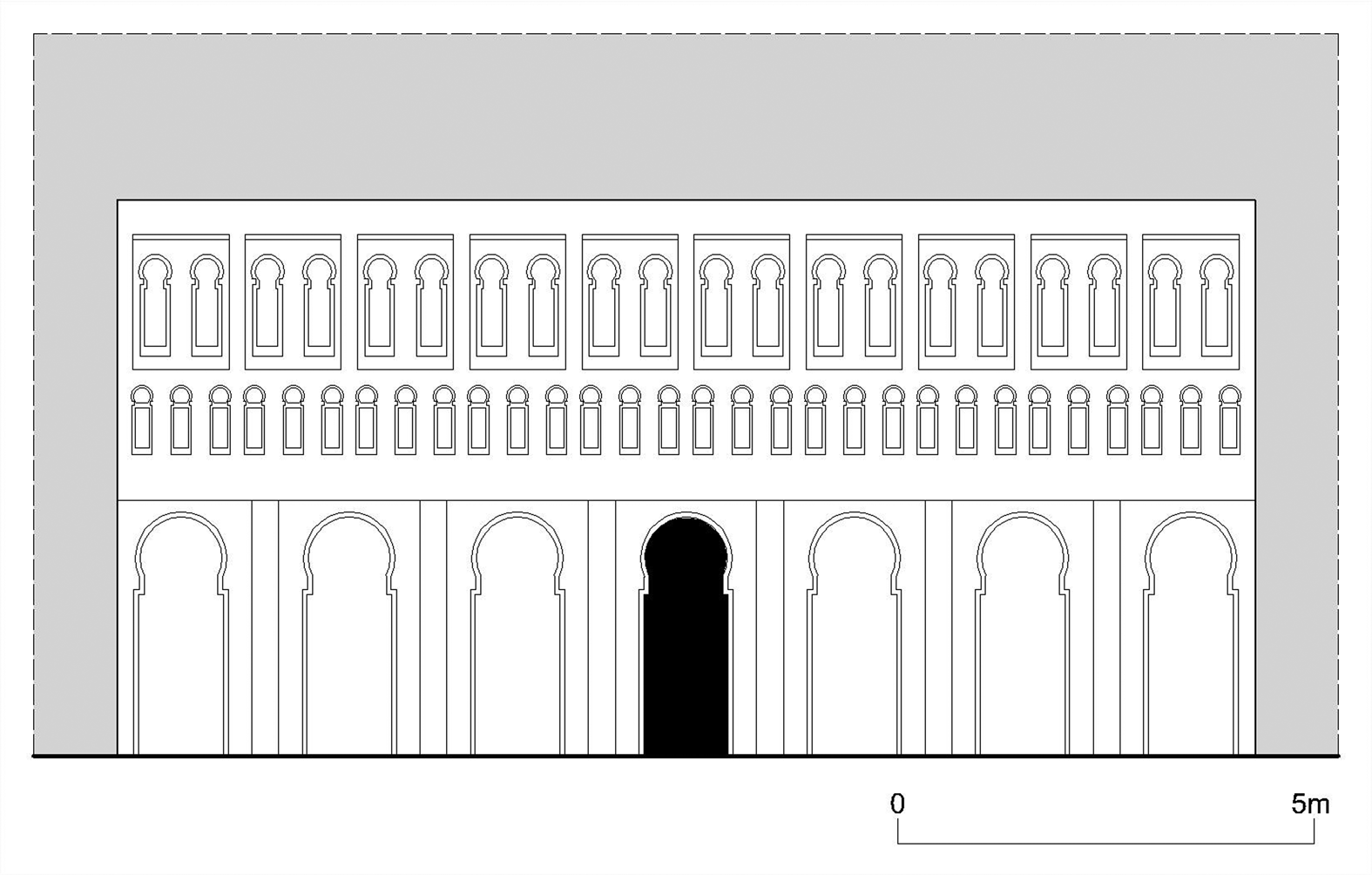

Fig. 5: Açıksaray, Area 5, restitution of the main façade (drawing: author)

Besides their distinctiveness in Cappadocia and the Byzantine Empire, cross-cultural stylistic features, such as the extensive use of horseshoe-shaped arches, attested in the broader territory within and beyond the Mediterranean, make the façades of these courtyard complexes all the more exciting and worthy of closer study. This article offers new insights into the discussion on the uniqueness of the façades of the courtyard complexes and questions the raison d’être of the ‘false’ monumentality in the rural setting of Cappadocia, testing it through three pairs of concepts: visibility and impressiveness; styles and types; inspirations and origins.

Visibility and impressiveness

Rock-cut architecture is practised not by an additive construction process but by extracting voids from the existing rock mass. Therefore, the three-dimensional adaptation of the exterior following the internal organization – in other words, the expression of the inner space in the outer mass, as in conventionally built architecture – is not necessary and is rare in Cappadocia.Footnote 8 Most church entrances in the region exhibit necessary openings with a minimum of decoration. Nonetheless, the courtyard complexes with their elaborate rock-cut façades, are the closest in appearance to conventionally built architecture (Figs 4–5).Footnote 9 The sculpted main façade of a courtyard complex ensures visibility and indicates the rock-cut architecture behind. The façades of the courtyard complexes often look as if they belong to multi-storey buildings, although the internal organization was, in most cases, only at the ground level. Like a three-sided (U-shaped) courtyard artificially carved into the rock, a high sculpted façade transfers courtyard complexes from the realm of the natural environment to the realm of built – human-made – environment.Footnote 10

In a typical courtyard complex, a three-sided (U-shaped) open courtyard, the sculpted main façade, and spaces of reception formed by the horizontal vestibule lying behind the main façade and the main hall lying perpendicular to the vestibule, were all aligned along the same central axis (Fig. 3). The axis that indicates a processional approach occasionally ended with a niche carved into the main hall's furthermost end. The niche points to a hierarchical organization of the space, and it may have been where the patron received guests.Footnote 11 The axis was underlined by the symmetrical decoration of the main façade, and the central door leading to the core of reception behind the façade. The axis was often further emphasized through a variation in the carved decoration on the ceiling of the vestibule and the main hall. Likewise, the main hall's lateral walls were occasionally decorated either with arcades or rows of blind niches that flanked and underlined the axis. Along this axis – the processional way – the consistency of decorative details, which differ from settlement to settlement, is also noteworthy. Only in few cases does the façade decoration continue along the courtyard's lateral walls, and even then only to a limited extent, since primary importance was given to the main façade in the centre and, accordingly, to the core used for the reception of guests.

The highly decorated façades of the Cappadocian courtyard complexes are not only instruments of the hierarchical and processional arrangement, enabling the rock-cut architecture to be perceived as ‘real’ and impressive. In a practical sense, they serve to make the complexes visible where they would otherwise merge with the surrounding landscape and disappear into it. In this sense, with their likeliness to be noticed from a distance, the façades of the courtyard complexes resemble the highly decorated portals centrally attached to the long blank walls of medieval Seljuk inns. From the thirteenth century onwards, these caravanserais were built at intervals along trade routes throughout Cappadocia and elsewhere in Anatolia. However, unlike the strictly introverted caravanserais, courtyard complexes are usually open on one or both sides, and so it can be concluded that safety was not a priority, as was the case with the caravanserais.Footnote 12 Above all, they differ radically from other Cappadocian rock-cut structures, such as the underground cities hidden below ground or behind cliffs. Obviously, the tenth to eleventh-century inhabitants of courtyard complexes felt safe and possessed a certain power: they chose visibility, in order to attract and impress people beyond their immediate boundaries, over seclusion and concealment.Footnote 13

Styles and types

In general, while the number and state of surviving façades of Byzantine ecclesiastical built architecture allow us to discuss stylistic variations and relative chronology, this is not the case with secular architecture, whether built or rock-cut.Footnote 14

Most of the courtyard complexes were probably decorated with façades, but many of these have not survived, due to erosion and human intervention. Based on a comparative architectural study of 43 courtyard complexes conducted by the author, 26 of 43 bear evidence of a sculpted façade.Footnote 15 Noticeable care was taken to cut and level the irregular rock into a vertical flat surface, and in many cases, horizontal mouldings divide this surface into two to four registers to give the appearance of a multi-storey building. Vertical pilasters are also used in some façades further to divide the registers into odd numbers of bays, and while these pilasters do not always continue through all the registers, in all cases the layout is symmetrical, and the principal entrance to be found in the centre.

The central door is usually a rectangular opening set in a horseshoe-shaped recess, with occasionally a pair of small keyhole-shaped windows cut into the lunettes above the door (Fig. 6). While horseshoe-shaped rather than semi-circular arch is used for the principal entrance, occasionally both types of arches are used together in the same façade. In some cases, additional entrances or blind niches of the same shape and size can be found on either side of the central entrance, which further underlines the symmetrical layout. The arrangement of the façades indicates a desire for monumentality and a desire for distinctness among its kind.Footnote 16

Fig. 6: Açıksaray, Area 1, the main façade (photo: author)

In some cases, as exemplified at Açıksaray, Area 1, the individual parts are emphasized by carving the pseudo-structural elements deeply (Fig. 6). In other cases, the total composition that combines the various elements in shallower carvings stands out as a whole as at Açıksaray, Area 5 (Figs 4–5).Footnote 17 Discussing courtyard complexes in Yaprakhisar, Veronica Kalas differentiates between two types of façade layouts, one where blind niches were carved in separate bays (as at Yaprakhisar Area 11), the other with a continuous blind arcade (as at Yaprakhisar Area 14).Footnote 18 Likewise, Robert Ousterhout differentiates between two systems of façade articulation: ‘a system of superimposed arcades, with minimal horizontal relationships, as at Açıksaray Area 5’ and ‘a sort of grid of horizontals and verticals, as in most of the Yaprakisar facades’.Footnote 19

A further distinction is achieved by using diversity in the arches and arcades in terms of shape, size and number. Furthermore, stepped carving is applied alternatingly either to the arch itself or to its frame, or the mouldings and pilasters. Surprisingly, although the ceilings and walls of the main halls and vestibules are often decorated with crosses, these are seldom found on the façades and are not in the foreground when they are. Likewise, although occasionally seen in the interiors, figure carvings are not used on the façades, while the lack of finely carved tangled decorations may be attributed to the limitations of the soft tuff stone.Footnote 20 Instead, some façades bear traces of painted decoration, such as zigzag motifs of red paint on a white background, or chequerboard motifs in red and white paint.Footnote 21

As for the courtyard's lateral walls, the shape and size of the lateral rock would often be unsuitable for carved decoration to the same extent as the main façade, nor was decoration the carvers’ aim. The processional central axis, adorned with the main façade and ending with the reception area at its heart, was emphasized to dominate the complex (Figs. 3–5). Even in the exceptional four-sided courtyard complex at Eski Gümüş, which is arranged around an enclosed courtyard, only the wall facing the entrance to the inner courtyard is decorated (Fig. 7).Footnote 22 On the other hand, some of the more distinctive details that dominated the main façade of a courtyard complex would often be repeated in the interior decoration of the vestibule, main hall and even of the attached church – where there was one – of the same complex, or of several complexes in the same settlement. The same workshops that decorated the façades also decorated the interior spaces, with certain nuances used as the signature of workshops and stamps of the patrons of the distinctive settlement. For instance, the complexes at Açıksaray feature a framed pair of horseshoe-shaped arches (Figs 4–5), and those at Çanlı Kilise exhibit the rows of gabled horseshoe-shaped arches (Fig. 8), while Eski Gümüş features deeply carved elongated arcading (Fig. 7).Footnote 23

Fig. 7: Eski Gümüş, the main façade (photo: author)

Fig. 8: Çanlı Kilise, Area 7, the probable main façade (photo: author)

The craftsmen who carved the façades and the rest of the complexes were most likely trained stonemasons. Engraved imitations of structurally unnecessary elements, such as impost blocks, show that the craftsmen were familiar with masonry techniques. Indeed, masonry architecture had a long tradition in central Anatolia.Footnote 24 Ousterhout even claims that medieval masonry architecture was more refined in Cappadocia than in the Capital. Nevertheless, he notes that very few examples from the tenth and eleventh centuries have survived in central Anatolia.Footnote 25 On the other hand, brick was a feature more closely associated with Constantinople, and it appeared rarely, mostly for decorative purposes, in central Anatolia.Footnote 26 Still, carvers of the façades of the courtyard complexes must have been familiar with the techniques and vocabulary of traditional masonry, brick, and hybrid structures; and they must frequently have encountered ancient rock-cut tombs in the area. This spectrum of available vocabulary in situ is reflected in various ways in the decoration of the rock-cut façades and interiors, though preferably in a symbolic manner. For instance, while red lines imitating stone courses were painted in the monolithic vaults, the paintings mentioned above of zigzag motifs on the façades recall brick courses’ decorative use.Footnote 27

Inspirations and origins

The uniqueness of the courtyard complexes’ rock-cut façades have prompted scholars to look at comparisons outside Cappadocian and Byzantine architecture: examples cited include façades of secular and religious architecture of the pagan, Christian and Islamic worlds from various locations across and beyond the Mediterranean, stretching from Persia and Transcaucasia to the Iberian Peninsula. The examples are often chronologically distant too, and further confusion arises from the varying materials and different construction techniques used. Frequently referenced examples in this respect include, among others, the Sassanian Taq-I Kisra palace at Ctesiphon and the Great Mosque of Cordoba.Footnote 28

Thomas Mathews and Annie Christine Daskalakis-Mathews were the first to note the secular character of the Cappadocian courtyard complexes in general. While pointing to the common use of the inverted T-plan and the horseshoe-shaped arch, they claim similarities among the Islamic palaces’ architecture, upper-class houses, and the Cappadocian courtyard complexes, which they even name ‘Islamic-style mansions’. They argue for a shared lifestyle between the elites of neighbouring cultures whose distinct status was reflected in houses along similar lines, regardless of religion and ideology.Footnote 29

Nevertheless, it is important to remember that the use of the horseshoe-shaped arch in the composition of monumental rock-cut façades can, on rare occasions, also be attested in a probable religious context, such as Ala Kilise located in the Ihlara (Peristrema) Valley, in Cappadocia (Figs 2 and 9). Indeed, the design of the façade of Ala Kilise bears a striking resemblance to the stylistic approach favouring the total composition exemplified in the courtyard complex in Açıksaray Area 5 (Figs 4–5).Footnote 30 Kalas points to the seemingly exceptional position of Ala Kilise, where a church dominates the space behind the decorated façade. She claims that ‘all of the monumental carved façades recorded thus far in Byzantine Cappadocia’ were found in the elite and domestic setting of the courtyard complexes. Having in mind the horseshoe-shaped arches on the façade of Ala Kilise, Kalas warns that ‘[i]slamicizing elements in a monument's features does not necessarily indicate a secular function’.Footnote 31 Indeed, in Cappadocia, in contrast to the scarcity of monumental façades that adorned religious architecture, the use of horseshoe-shaped arches was not restricted to the secular sphere: such arches decorated the interiors of many churches. They were even used in the plan and elevation of the apses.Footnote 32 Likewise, Ousterhout highlights the ‘blind arcades with horseshoe-shaped arches’ as ‘the norm’, which appeared ‘in varying levels of complexity throughout Cappadocia’.Footnote 33 On the other hand, Mathews and Daskalakis-Mathews accuse earlier scholars of ignoring ‘an important clue’, namely the horseshoe-shaped arch, despite its frequent appearance in Cappadocian structures, due to its association with Islamic architecture.Footnote 34 It can be concluded that such decorative elements as horseshoe-shaped arches would not have been so laden with ideological meanings as we often think of them today and that the term ‘islamicizing’ alone needs to be reconsidered.Footnote 35

Fig. 9: Ala Kilise at Ihlara Valley (Peristrema), the main façade (photo: Robert Ousterhout)

By contrast, and with more acuity, Lyn Rodley suggests looking at local examples such as Ala Kilise, a masonry church, on Ali Suması Dağı in the neighbouring Lycaonia rather than ‘exotic [Near Eastern] sources’ for comparison.Footnote 36 Although there is indeed an occasional use of similar elements, such as the horseshoe-shaped arch and blind recessed arches or arcades, elsewhere in central Anatolia, none of the existing built structures seems to offer a superimposed façade arrangement similar to that of the courtyard complexes. While Rodley, still admitting the likelihood of a ‘loosely defined’ vocabulary that Cappadocian façades and Near Eastern examples may share, points to the common legacy of the Hellenistic world,Footnote 37 Nicole Thierry stresses that the Hellenistic heritage was variously translated depending on the region and materials: for instance, she stresses that in medieval Georgia, the arch was ‘stretched’, while in Cappadocia it was ‘multiplied’.Footnote 38 However, in Cappadocia, in some cases, as in Eski Gümüş, one notices façade arrangements reminiscent of Thierry's ‘Georgian’ type (Fig. 7). From this, it may be deduced that Cappadocia, being outside the major centres but on the main road that connected them, was more receptive and less selective in this sense. Above all, the nature of rock-cut architecture freed craftsmen from the material and structural concerns associated with masonry and brick architecture, enabling them to create designs based primarily on formal visual appreciation.Footnote 39

However, regarding the readiness to borrow, Ousterhout represents another point of view. He asserts that for ‘the provincial elite of Cappadocia … the cosmopolitan court culture of Constantinople would have been the most immediate source of inspiration.’Footnote 40 Unfortunately, the only surviving secular example from Constantinople is the façade of the late thirteenth-century so-called Tekfur Palace. Indeed, although a later building, its superimposed façade arrangement recalls those of Cappadocian courtyard complexes.Footnote 41 Nevertheless, it should be noted that instead of horseshoe-shaped arches that were extensively used on Cappadocian façades, semi-circular arches were used on the façade of the Tekfur Palace.

Concluding remarks: patronage and monumentality

The varying state of the evidence, coupled with the Cappadocian patrons’ readiness to borrow and the carvers’ inventiveness in adapting the various vocabulary into the unique setting of the rock-cut architecture, may explain the difficulty of defining stylistically conclusive types for the Cappadocian façades. It is unlikely that the question of origin will ever be answered with certainty: it is likely that throughout the Mediterranean and beyond, there was a mutual, multi-faceted and continuous interchange and transmissions of ideas.Footnote 42 Indeed, the various Mediterranean and neighbouring cultures in question have intermingled so profoundly and for so long that any attempt to investigate the origin and transformation of a common particular architectural element, such as the horseshoe-shaped or the pointed arch, cannot be easy. Neither has the issue been free of scholarly preconceptions rooted in a dichotomy between East and West.Footnote 43

For Cappadocian façades, the primary question to ask concerns neither style nor origin, but patronage and monumentality. Who were the patrons and what were the motivations for the patronage of monumental architecture in this rural domestic setting? The dating of courtyard complexes to the tenth to eleventh centuries corresponds to the brief period of security and prosperity between the Arab attacks of the eighth and ninth centuries and Seljuk arrival after 1071.Footnote 44 Cappadocia, a frontier zone for most of the period, was one of the regions where military aristocracy originated.Footnote 45 Accordingly, the majority of these complexes most likely belonged to the military aristocracy which owned extensive land and dominated the region during the tenth and eleventh centuries.Footnote 46 Settlements near medieval military installations, such as Çanlı Kilise and Selime-Yaprakhisar, suggest an even more direct association, while the settlement at Açıksaray, with its number of large stables, might have supplied the army with horses (Fig. 2).Footnote 47

Although tending to identify most of the Cappadocian rock-cut structures as monastic, when it comes to their façades, Spiro Kostof is very clear:

This [the rock-cut façade of Sümbüllü Kilise in Ihlara (Peristrema) Valley, in Cappadocia] is no product of rustic imagination. The monk who envisaged it could not have been innocent of monumental architecture. Indeed, there can be little doubt that the original progenitors of this and all the other Cappadocian frontispieces to monasteries are Late Antique façades to palaces, formal fountains ‘nymphaea’, and theater stages.Footnote 48

The fact that the ‘false’ façades of courtyard complexes were not required to be in accordance with the interior and the structure recalls indeed the façades of monuments of late antiquity, which were maintained as witnesses of the cities’ past greatness, while their interiors were of less concern and were divided into small houses, or even ransacked.Footnote 49

Ousterhout claims that ‘[b]uilt architecture, accorded higher prestige, was the referent of the elaborate rock-cut forms’.Footnote 50 It was through the façades that the expression of the status of the patrons spoke loudest, and so it is no surprise that the sculpted façades of the Cappadocian mansions recall the common ‘language of power’ that has been applied here and there across the Mediterranean at least since the Roman period.Footnote 51 While the ‘false’ monumentality might have allowed the complexes to dominate their rural environment, details inspired by a wide range of sources also allowed the competitive patrons to differentiate among themselves.

To conclude: rock-cut façades in Byzantine Cappadocia, not only in terms of appearance but also in terms of material, were humble reflections of the on-going contest for grandeur imitating imperial level that can be traced – if not earlier – back to that between the Romans and the Sasanians, then between the Sasanians and the Byzantines, and finally between the Byzantines and the Caliphate.Footnote 52 When all else might fail, one statement can be made with some certainty: that the ambitious patrons of rock-cut courtyard complexes pursued the ‘illusion of power’ provided by ‘false’ monumentality, and that what remains of the secular medieval architecture in Cappadocia is to a large extent but this illusory palimpsest.

Fatma Gül Öztürk Büke is Associate Professor at Çankaya University. She studied architecture at the Universität Stuttgart and received her PhD in Architectural History from the Middle East Technical University (Ankara) in 2010. She has been a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania (2013–14). Her research interests include Byzantine Cappadocia, rock-cut architecture, housing and settlement in the Mediterranean.