Party polarization is often cited as one of the primary causes for the political dysfunction currently plaguing American politics (Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz2013; Jacobson Reference Jacobson2013). Recent analyses have focused on its possible causes as way to assess the problem and ascertain solutions (Barber and McCarty Reference Barber and McCarty2013). Polarization reflects the ongoing back-and-forth between political elites and the electorate that has characterized American politics since the advent of political parties in the nineteenth century. While political scientists differ over the extent of the polarization among these groups (Abramowitz and Saunders Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008; Fiorina et al. Reference Fiorina, Abrams and Pope2008; Layman et al. Reference Layman, Carsey and Horowtiz2006), they do recognize how elites may contribute to polarization by attempting to forge winning electoral coalitions through setting the agenda of issues to be discussed and in what capacity by framing the parameters of debate (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1989). In nineteenth-century America, these attempts by elites to exercise control over their political environment and amass sustainable electoral coalitions characterized the burgeoning party system.

Beginning in the 1830s, and continuing over the next 60 years, a two-party system developed, at first between the Democrats and Whigs, and later between the Democrats and Republicans, in which the parties transformed from pluralistic entities into two relatively organized electoral organizations—although they still may be regarded as national associations of state parties because the state remained the most important level of party organization throughout the nineteenth century (Kleppner Reference Kleppner1979; McCormick, R. L. Reference McCormick1986; McCormick, R. P. Reference McCormick1973; Silbey Reference Silbey1991). National party leaders attempted to build broad electoral alliances by reconciling local and state interests into a national coalition. Building such a coalition forced party leaders to address the concerns of their constituents as well as other political elites.

Scholars of nineteenth-century political history have explored party development from voter alignment, to organization, up through elite activity and strategy. Yet, few studies have focused on development through a comprehensive analysis of the official electoral appeals of a party on the state and national level—the platform. Platforms were the most authoritative public expression of each party’s issue positions and general philosophy. In the nineteenth century, each party served as the key identifier to the public in an election. Their platforms, drafted at party conventions, articulated the core principles on which a party would run in an election. Once the party ratified the platform at the state or national convention, all members of the party had to “fall into line” behind it (Silbey Reference Silbey1991: 68).

This study utilizes a content analysis of platforms issued by the national and state affiliates of the Democratic and Whig/Republican parties during presidential election years from 1840 to 1896 to gauge party polarization; such an approach allows for comparisons of the parties across time, regions, and states. I argue that throughout this period the major parties on the state and national level offered divergent positions on similar policies. This analysis may illuminate elite electoral strategy in any given election and across multiple elections by answering questions as to when and how the platforms of the Democrats and Whig/Republicans converge or diverge in issue content and salience over time.

Literature Review: Polarization in the Party Period

Numerous accounts of nineteenth-century political history attest to the pervasive nature of parties in the fabric of American society. The appearance of mass-based political parties dramatically affected the trajectory of American political development (Altschuler and Blumin Reference Altschuler and Blumin2000; Holt Reference Holt1999a, Reference Holt2001; McCormick, R. L. Reference McCormick1986, McCormick, R. P. Reference McCormick1975; Silbey Reference Silbey1991, Reference Silbey2001).

First, the development of mass-based political parties involved the formation of an ideological framework. Party leaders constructed a set of beliefs, ideas, and symbols around which to build a party and electoral following (Silbey Reference Silbey1991: 73; Ware Reference Ware2006: 34). That said, the construction of this ideological might have come after the formation of the parties. Andrew Jackson served as the impetus for the creation of the Democrats and the Whigs. While the latter may have initially coalesced in opposition to Jackson, they soon understood the need to craft an ideology to engage the electorate. The foundational ideologies of the Democrats and Whig/Republicans often affected the articulation of divergent policy positions by the two parties.Footnote 1 The Democratic Party of Jackson and Van Buren adopted the core antistatist policies of its ancestral Jeffersonian party. Party leaders used negative government rationale to oppose economic policies, such as the protective tariff and national bank; developmental policies, like publicly funded internal improvements; and cultural policies, such as temperance. The Whig/Republicans, in contrast, adopted more positive government, prostatist positions. Policies endorsing a protective tariff, national bank, publicly funded internal improvements, and public promotion of morality, such as sumptuary laws, constituted a great deal of the Whig program (Aldrich Reference Aldrich2011; Foner Reference Foner1995; Gerring Reference Gerring1999; Gienapp Reference Gienapp1987; Holt Reference Holt1999b; Howe Reference Howe1979; Watson Reference Watson2006).

In addition to the construction of an ideological framework, voter alignments represent an avenue to assess polarization. It had traditionally been considered that economic-class affiliations influenced voter support for a particular party (Beard Reference Beard1957), but further analysis revealed that voter ethnicity and culture may have been a more influential determinant of party allegiance (Benson Reference Benson1961; Jensen Reference Jensen1971; Kleppner Reference Kleppner1970). While the broader ideological concerns manifested in issues such as economics and states’ rights may have been the cause for antagonisms among political elites, issues that reflected the ethnocultural and ethnoreligious backgrounds of the voting public tended to contribute toward interparty divisions, complicating the crafting of a broad electoral coalition (Gerring Reference Gerring1999). Generally, the Democrats’ approach to religious and cultural matters, whereby they advocated a strict separation of the private and public spheres, contributed to their increased attraction to Catholic immigrants. The Whig/Republican Yankee Protestant foundation resulted in the merging of the public and private spheres. This outlook manifested in policies that tended to regulate morality, such as sumptuary laws (Gerring Reference Gerring1998; Holt Reference Holt1999b; Howe Reference Howe1979). Studies highlighting regional variation, however, have questioned the rigidity of these alignments (Benson Reference Benson1961; Formisano Reference Formisano1994; Kleppner Reference Kleppner1979; McCormick, R. L. Reference McCormick1974; Silbey Reference Silbey1991). Further studies have demonstrated the prominence of economic concerns as a driving force in the partisan debate of the time (Bensel Reference Bensel2000; Gerring Reference Gerring1999; John Reference John2004).

While ideological and voter alignment analyses may reveal a picture of interparty demarcations in the electorate, studies of congressional voting behavior depict polarization in government. Overall, studies of congressional voting behavior of the two parties do reflect clear differences regarding activity and policy stances. Poole and Rosenthal (Reference Poole and Rosenthal1997, Reference Poole and Rosenthal2001) posit that congressional members often spilt along class and economic issues and less often along sectional issues. They demonstrate that over time there is a consistent and noticeable polarization between the voting preferences of Democratic and Whig/Republican members of Congress on economic policy. This corresponds to other analyses that reveal a Congress polarized along party lines in the 1840s, less so in the 1850s (save for 1856), and one that experiences a gradual increase in interparty polarized voting throughout the Gilded Age (Alexander Reference Alexander1967; Brady and Althoff Reference Brady and Althoff1974; Brady et al. Reference Brady, Brody and Epstein1989).Footnote 2

Yet, this narrative of stark polarization, at least as it pertains to post-Reconstruction America, might be overly simplistic and “not a reliable indicator of the ideological distance between the two parties on national issues” (Lee Reference Lee2016: 11). In an examination of congressional roll-call votes from 1876 to 1896, Lee (Reference Lee2016) finds few issues on which the two parties are truly polarized. While the parties may have been “highly partisan,” they were not polarized in terms of offering “clear, strongly divergent positions on national policy questions” (10). Most of the votes in this period reflect members trading in “particularized benefits,” such as patronage, rather than in “position-taking” (6). Thus, Lee prefers conflict above polarization to characterize this period.

These studies of the nineteenth century describe the political debates and the party competition from ideological and institutional perspectives. They go into detail about the motives of the elites and the political environment, mostly by describing speeches, editorials, and other public statements by elites, as well as congressional voting records. Those that do incorporate platforms do so by mentioning stances in a specific election or a few successive elections (Bensel Reference Bensel2000; Benson Reference Benson1961; Chester Reference Chester1977; Gerring Reference Gerring1998; Holt Reference Holt1990, Reference Holt1999b; Silbey Reference Silbey1991). For example, while Bensel (Reference Bensel2000) focuses on state platforms from the latter quarter of the nineteenth century, this analysis spans 1840 to 1896. And, although Gerring (Reference Gerring1998) analyzes most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to gauge party ideology, he references primarily national party platforms and related speeches and documents of state and national leaders. When he does consult state party platforms, it is to assess party ideology more broadly (296). This project intends to complement those studies through a methodological examination of platforms on the state and national levels, which is necessary to assess party polarization and offer an insight into elite strategy more fully. Thus, this analysis is the first inclusive examination of the state and national platforms of the Democratic, Whig, and Republican parties in the nineteenth century. Moreover, while scholars have attempted to measure polarization through analysis of national platforms in the twentieth century (Coffey Reference Coffey2011; Jordan et al. Reference Jordan, Webb and Wood2014; Kidd Reference Kidd2008), there are no studies to date that focus on nineteenth-century platforms in this manner.

Therefore, to gauge polarization, this analysis is geared around three main arguments: (1) the platforms of the Democratic and Whig/Republican parties converge in issue content and emphasis over the nineteenth century; (2) the platforms of these two parties offer divergent positions on similar policies; and (3) the platforms of the major parties are more divergent on economic issues.

The first proposition relates to partisan agenda setting and the relationship between the national and state party organizations. The second proposition builds on the previous one by directly addressing the degree of polarization between the two parties. The third proposition hones more specifically on the issues that seemed to cause the most polarization between the two parties over the party period. The chance that the platforms of the major parties are more divergent on economic issues may offer insight into elite strategy over which issues the parties deemed the most appropriate and necessary to articulate the clearest policy alternatives, as well as the issues on which they deemed the most preferable to forge a cross-sectional national coalition. Economic issues may be better suited to appeal to a more heterogeneous population, rather than cultural issues, or state and local concerns, which speak to more regional or localized interests (Gerring Reference Gerring1999; Ware Reference Ware2006).

To present these arguments in the clearest and most effective manner, the argument is structured as follows: a description of case selection and the methods of analysis; the data findings in relation to each of the propositions; a discussion of the results; and a few concluding points.

Research Design

Platforms are the only document debated and voted on by the entire party on either the state or national level. As a result, a single platform “most fully represents the party’s intentions” in any given election (Pomper Reference Pomper1967: 319). This is especially true of the campaigns during the “party period” of the second- and third-party systems in the nineteenth century, when party labels served as key identifiers to the public. Platforms reinforced this identity (Benson Reference Benson1961: 216–53; Janda et al. Reference Janda, Harmel, Edens and Goff1995). Although newspaper editorials and stump speeches intensify the debate on the ground, the platforms crafted by party leaders help frame that debate. They are elite documents crafted by a Resolutions Committee selected at the state or national convention.Footnote 3

The degree of policy detail in a program can provide insight into the party’s strategy in an election or if that party gains office (Ginsberg Reference Ginsberg1976; Monroe Reference Monroe1983). Parties do not take a position on all issues of concern, nor do they always issue a clear stance on an issue (Chester Reference Chester1977: 36–38). By depicting the stated positions of the parties in an election, platforms link party ideology, the electorate, and parties in government to offer a more comprehensive picture of polarization and conflict. For example, party leaders of the latter nineteenth century viewed their state party platforms as binding and tried to introduce and advance legislation based on those issues in the state legislatures and on the national level (Bensel Reference Bensel2000: 110–11). While the congressional roll-call votes on an issue like the tariff may reflect competing sectional concerns within each of the parties (Lee Reference Lee2016), the state and national platforms from corresponding years may depict complementary or competing patterns. Platforms of the post-Reconstruction period, for example, reveal Democrats and Republicans staking out opposing positions on the protective tariff—in opposition to and support of, respectively. Lee’s analysis, however, portrays congressional Democrats willing to modify their stance on legislation to appease the regional concerns of its members, such as when Louisiana Democrats struck a deal to protect its sugar industry (ibid.: 9). Thus, an analysis of the platforms of the nineteenth century may illuminate elite strategy by depicting which issues appeared when, where, and to what degree.

Platform Data Set

The data set includes all the national platforms and representative state platforms of the Democratic and Whig/Republican parties for the presidential election years, 1840 to 1896. The states represented in this study are California, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Massachusetts, Missouri, Nebraska, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia.Footnote 4

Method of Analysis

Each platform represents a case, and is categorized according to party, state, region, and year. Policy references in the platforms are coded according to a specific issue area and placed in one of seven domains: economics, culture, government and political institutions, statism, labor, foreign policy, and slavery and black civil rights.Footnote 5

Each policy reference is coded by taking the largest continuous block of text, or words referring to that specific issue. The presence of that issue is calculated by summing up its total word count in that platform. Because the platform drafters often listed unrelated issues in a single sentence, these quasisentences represent the simplest approach to measuring the presence of an issue in a platform. Quasisentences, which serve as the unit of analysis, can be as large a unit as a paragraph or as small as a couple of words (Budge Reference Budge2001).

Polarization is gauged according to issue salience, position, and variance.Footnote 6 Salience refers to the presence of an issue in a platform relative to the presence of the other issues in that platform (Klingemann et al. Reference Klingemann, Hofferbert and Budge1994: 25). The overall character of the quasisentences on an individual issue is used to assess the position of the party in a certain platform. Variance refers to the variation in the salience of an individual issue variable, such as temperance, or a larger domain variable, such as culture, relative to that issue in other platforms. The selective emphasis and stated position of issues in platforms help to illustrate how party leaders attempted to differentiate themselves from each other and in the eyes of the voters (Budge and Farlie Reference Budge and Farlie1983: 25).

Methodological Considerations

Nineteenth-century American party platforms are useful for analysis, but they do have limitations regarding their utility in purely quantitative analyses. Coding and content analysis exhibit such limitations.

The categorization of issues into different domains can be seen as subjective in the sense that the researcher constructs the domains based on their reading of the material. At times, this categorization reflects a contemporary understanding of an issue that may differ from how political actors viewed it at the time. For example, while I code “internal improvements” in the statism domain, nineteenth-century politicians may consider it as an economic issue. I attempt to mitigate the shortcomings of this possibility by adapting categorization schemes of other scholars in the field, such as Bensel (Reference Bensel2000) and Gerring (Reference Gerring1998), to hopefully provide consistency across the canon and to situate this study in the field more effectively.

The approach to coding the platforms in this study mirrors the one employed by the Comparative Manifesto Project (Klingemann et al. Reference Klingemann, Volkens, Bara, Budge and Macdonald2006) and other researchers of American party platforms (Alphonso Reference Alphonso2015; Bensel Reference Bensel2000; Feinstein and Schickler Reference Feinstein and Schickler2008; Gerring Reference Gerring1998; Holt Reference Holt1990; and Oliver and Marion Reference Oliver and Marion2008). While computer programs have become more common to conduct content analysis of texts, presumably because they yield more reliable results by removing the subjectivity of the coder as best as possible (Jordan et al. Reference Jordan, Webb and Wood2014; Kidd Reference Kidd2008; and Laver et al. Reference Laver, Benoit and Garry2003), this study employs the more traditional hand-coding technique, which allows for a closer examination of the text and facilitates complementary qualitative analysis.Footnote 7 Evolving terminology throughout the nineteenth century necessitates a more nuanced reading of the platforms to ascertain the party’s policy position accurately. References to currency, such as to gold, silver, and specie—coin or paper—illustrates this difficulty. In 1864, California Democrats oppose “laws tending to substitute a paper currency in California in place of our own metallic circulating medium” and, in 1876, their Republican rivals “favor a return to metallic currency” (Davis Reference Davis1893: 198–199, 208, 357; italics added). While both platforms reflect similar positions, training software to code them accurately poses challenges due to the different phrasing and terms qualifying currency.

Platforms assist in determining a “party’s position on specific issues,” but not for gauging its general philosophy or “electoral mission” (Gerring Reference Gerring1998: 294). As a result, content analysis ascertains differences between the statements of the parties that helps illuminate patterns, such as when, where, and under which conditions an issue appears more salient, but it cannot ascribe intent (Holt Reference Holt1990: 4, 372). Therefore, an analysis of nineteenth-century platforms should include descriptive analyses of the contexts surrounding the adoption of the platform, issues, and election to provide a fuller account of the decision-making process.

While a content analysis of platforms provides challenges, I consider these limitations in assessing the findings and drawing conclusions. The analysis highlights patterns and offers descriptions of what may affect those patterns. Platforms constitute a piece of the larger puzzle, alongside studies of political ideology, voter alignment, and congressional roll-call votes, that enhance our understanding of party development and elite electoral strategy.

Findings

Overall, the data support the first proposition that the platforms of the Democratic and Whig/Republican parties converge in issue content and salience over the nineteenth century. First, table 1 provides the absolute value for the differences in salience for each issue between the Democrats and Whig/Republicans over the years. For example, in 1852, the average salience for economic issues in all Democratic platforms is 31.77. In other words, the Democrats devoted about 32 percent of each of their platforms to references to economic issues on average in 1852. The Whigs devoted 21.74 (22 percent) of their platforms references to economics in that year. Therefore, the salience difference on economic issues between the two parties in 1852 is 10.0. A larger salience difference on an issue relative to other issues in a specific election year indicates more divergence between the parties.

Table 1 Difference in average salience of each issue between the Democratic and Whig/Republican Party platforms—state and national, 1840–96

The largest reference gaps between the parties occur in 1840 and 1848, in which the Whigs intentionally chose not to issue a national platform (Holt Reference Holt1999b: 101–5, 320–29; Moore, et al. Reference Moore, Preimesberger and Tarr2001: 444, 449). In 1840, the Whigs’ decision should not be viewed as avoiding issues, but rather their desire to maintain a tenuous anti-Democratic coalition focusing on the key issue of opposing the Jackson administration (Holt Reference Holt1999b: 105; Moore et al. Reference Moore, Preimesberger and Tarr2001: 444). In 1848, the Whigs, beset by internal divisions, failed to adopt an official platform (Holt Reference Holt1999b: 329–30). At a separate mass ratification meeting held in the evening on one of the convention days, the party adopted a list of resolutions, but did not address any substantive policies (Chester Reference Chester1977: 59–60; Moore et al. Reference Moore, Preimesberger and Tarr2001: 449). The document primarily extols the virtues of their nominee General Taylor and encourages “all party members to work on his behalf” (Silbey Reference Silbey2009: 70).

Interparty Consensus on Issue Salience

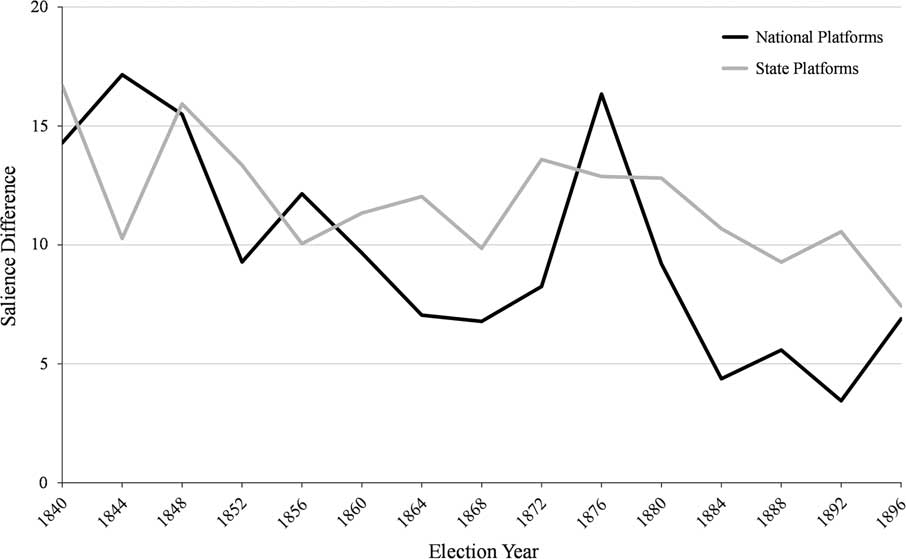

Although the pattern in table 1 depicts fluctuations between convergence and divergence in the salience differences for each issue between the parties, it does not clearly convey convergence. A growing consensus is illustrated, however, by comparing the difference in issue salience between the national and state parties. Figure 1 graphs the average overall difference of platform salience between the two parties on the national and state levels. The overall salience difference refers to the absolute difference between the two parties in their average emphasis in each specific issue area. These differences are then averaged to obtain an overall difference in issue salience, which is essentially the average difference in the coded portion of the platforms. The smaller the difference in average issue salience the more alike are the parties in what issues are represented and to what degree in the platforms.Footnote 8 Figure 1 depicts a gradual decline in the differences between the two parties on both the national and state levels. The national platforms are markedly more convergent over time than the state parties. This difference in the degree of convergence may be reflective of the antagonism between the national parties and their state affiliates; the salience of state and local concerns, such as sumptuary laws, state budgetary matters, and the debate over local natural resources; and the variation in the number of state platforms over time.

FIGURE 1 Difference in average salience of all the issues between the National Democratic and Whig/Republican Party platforms and the state Democratic and Whig/Republican Party platforms, 1840–96. Note: The trend lines indicate the absolute difference in the average platform issue salience between the Democratic and Whig/Republican parties in each state and on the national level from 1840 to 1896. The smaller the difference in average issue salience, the more alike are the parties on each level in what issues are represented and to what degree in the platforms.

The national platforms reflect a pronounced divergence in 1876, primarily due to the Democrats devoting more than 50 percent of their platform to economic issues and more than 28 percent to government and political institutional issues. The state platform divergence from 1880 to 1892 results from the differing attention to economic, government and political institutions, statism, and slavery and black civil rights issues. In 1880, all the states differ in their average salience between 13.0–15.0, except for Indiana, which is substantially more convergent at 4.0. The main cause for the difference in Massachusetts is that the Republicans devote 38 percent of their platform to protecting the suffrage rights of the black population:

But we owe it to our self-respect to the settled convictions of Massachusetts, to our obligations to the freedmen of the nation, and to truth, unequivocally to declare that so long as the colored or any other citizens of the United States are prevented by intimidation or violence from exercising the great rights of free discussion and free suffrage or are defrauded of the results of their ballots by false counting, so notorious that it is scarcely denied, our voices shall be heard in loud, constant, and indignant protest and we will invoke the public opinion of the country and of mankind in condemnation of these atrocious acts not only upon their authors but also upon that political party which tolerates or condones them. (“Massachusetts” 1881; New York Times 1880)

In 1884, New York has a salience difference of approximately 20.0, which is due to the Democrats issuing a very brief platform. Approximately 60 percent of the language is devoted to extolling the virtues of previous state and national platforms. The one issue of substance refers “to the duty of the Legislature to respect the popular vote in 1883 for the abolition of the contract system of labor in the prisons” (New York Tribune 1884).Footnote 9 The Republicans issue a lengthier platform, 60 percent of which is devoted to economic concerns, such as the “adherence to a sound financial policy which dictates the important suspension of the coinage of the standard silver dollar, the retirement of the trade dollar and the inflexible adjustment of the currency to the single standard of gold” (Republican Party n.d.).

In 1892, the South Carolina Democrats allot 83 percent of their platform to economics (New York Times 1892). Their Republican counterparts only apportion 14 percent to economics, while devoting the lion’s share to government and political institutional and statism concerns (a salience of 42.0 and 27.0, respectively). The Democrats address the state debt, while the Republicans focus on election law reform and the importance of the state in educating its citizens, so “that in liberal, progressive education the future weal and prosperity of the Commonwealth is assured” (News and Courier 1892).

Interparty Divergence on Issue Position

Second, the argument that over time, the platforms of Democratic and Whig/Republican parties offer divergent positions on similar policies seems to be supported overall. On core ideological issues, each party stakes out opposing positions for the bulk of the period.

The policy issues that polarized the parties usually involved debate over the role of the national, or general government, which reflected the Democrats’ and Whig/Republicans’ antistatist and prostatist ideologies, respectively (Gerring Reference Gerring1998; Holt Reference Holt1999b; Howe Reference Howe1979; Ware Reference Ware2006: 11–13). Throughout most of the period, the issues that represent these ideological foundations, and thus on which the parties were most polarized, are the tariff, publicly funded internal improvements, and states’ rights. The Democrats generally opposed a protective tariff, the national government’s funding of internal improvements, and defended state sovereignty against encroachment by the national government. The Whig/Republicans, in contrast, integrated the perpetuation of the protective tariff into its core economic policy, supported the role of the general government in financing infrastructure development, and generally viewed strident states’ rights rhetoric as a threat to the union.

Figure 2 depicts interparty polarity by incorporating the positional salience on these issues throughout the period.Footnote 10 The trend lines in this figure represent the positional salience for tariff protection, internal improvements, and states’ rights for the Democratic and Whig/Republican parties on the national and state levels in each election year. The national trend lines denote the positional salience of each party on the issue in each election. The state trend lines represent the mean of the positional salience of the issue across the state party affiliates.Footnote 11 Each individual issue is paneled to compare the national and state parties.

FIGURE 2 Positional salience of issues—tariff, state’s rights, and internal improvements—between the Democratic and Whig/Republican party platforms—state and national, 1840–96. Positional salience refers to the combination of the position and salience of an issue in each platform. Each issue is paneled to gauge party polarization of the Democratic and Whig/Republican parties from 1840 to 1896. The national trend lines simply denote the positional of each party on the issue in each election. The state trend lines represent the mean of the positional salience of the issue across the state party affiliates.

The Democrats and Whig/Republicans on the national and state levels stake out opposing positions on the protective tariff to the same degree consistently over time. On internal improvements, the Whig/Republicans steadily support nationally financed infrastructure projects, but their opponents shift their position over time. The state Democrats remain generally opposed to it, save for the 1860 election and for a slight positive positional salience in the 1890s (primarily due to the Texas Democrats needing to develop their roads and river ways), and the national Democrats become gradually more supportive over time (Williams Reference Williams2007).

Regarding states’ rights, platform statements reflect the state parties hewing to the traditional positions. The data do indicate, however, a national party willing to alter or hedge its position to address a turbulent electoral environment. For example, in attempt to assuage the fears of the southern states, the nascent national Republican Party endorsed a certain degree of state authority in its 1860 platform:

That the maintenance inviolate of the rights of the states, and especially the right of each state to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively, is essential to that balance of powers on which the perfection and endurance of our political fabric depends; and we denounce the lawless invasion by armed force of the soil of any state or territory, no matter under what pretext, as among the gravest of crimes. (Porter and Johnson Reference Porter and Johnson1961)

While this plank refers to the extension of slavery, specifically the turmoil in Kansas because of the policies of the Buchanan administration, the party phrased it in such a way as to blunt Democratic critiques and fears of an abolitionist party. The Republicans downplayed antislavery rhetoric in favor of language endorsing states’ rights. The prefatory clause stipulating the rights of the states as inviolate is the operative clause in the plank (Chester Reference Chester1977: 76–78; Holt Reference Holt1990: 282–84; Moore et al. Reference Moore, Preimesberger and Tarr2001: 457–58).

In contrast to the protective tariff, internal improvements, and states’ rights, other salient issues, such as economy in government expenditures, pensions, and civil service reform, did not evoke such polarized responses from the parties. This approach may highlight electoral strategy and constraints on party leaders. Staking out a position on retrenchment and economy in government expenditures was simply not controversial. Neither party wanted to be viewed as fiscally irresponsible. Pensions for Civil War veterans was a linchpin in the postwar economic and political strategy of the Republican Party, but the nature of the issue inhibited the Democrats from staking out a staunchly oppositional stance (Bensel Reference Bensel2000: 500–6; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992: 102–51). Civil service reform constrained both parties in such a way as to only elicit favorable stances.

Polarization on Economic Issues

Third, the data support the proposition that the platforms of the major parties are more divergent on economic issues than on any other issue for the bulk of the party period. Divergence refers to variation in the salience of economics in each of the platforms and the parties’ position on these issues. While parties addressed economics more than any other issue for the bulk of the period, the variation in platform content—salience and position—results from the specific economic issues referenced in their platforms.

Economics are particularly salient in the 1840s, wane in the 1850s, and regain prominence in the Gilded Age. Platform content on these issues is reflected through a comparison between the variations in the average salience of all the platform issues and the average salience of the platform issues excluding economics. Figure 3 graphs the variance of salience for all the issues. The trend lines represent a composite figure of the means for each of these issues in each platform in a year. The lower the point in the line, the more similar is the platform content of the parties. A spike in the line indicates dissimilarity in platform content. The crucial difference between the two trend lines is that one of them excludes economic issues from the overall calculation. The influence of economic issues as a divergent force is evident when comparing 1840, 1844, 1892, and 1896 to the rest of the period. Variation around the mean spikes in these elections when economic issues are included in the calculations. In comparison, when economic issues are excluded, the variance line does not peak as high in the 1840s and continues its downward trend through the 1892 and 1896 elections.Footnote 12

FIGURE 3 Variance in salience of all the issues between the Democratic and Whig/Republican Party platforms—state and national, 1840–96. The trend lines indicate the variance around the mean of the platforms in each election year of the Democratic and Whig/Republican parties from 1840 to 1896. The “average (all issues)” line represents a composite calculation of the means for each issue in each platform in a year. The “average (without economics)” line follows the same procedure but excludes economic issues from the calculation. The lower the point in the line, the more similar is the platform content of the parties. A spike in the line indicates dissimilarity in platform content. The major trend line is derived through a calculation of the mean and standard deviation of each domain in each election year to yield an average weighted standard deviation for that year.

The influence of economic issues is also suggested when gauging issue salience across the period and data set. The trend line excluding economic issues depicts convergence over time. The data indicate a correlation between issue salience and divergence—the more salient economics are in the 1840s, 1880s, and 1890s, the more the platforms diverge in issue salience.

Discussion: Polarization in the 1850s and 1890s

The analysis of the platforms reveals patterns of polarization in two distinct periods: The 1850s exhibit the greatest divergence regarding issue salience and the 1890s exhibit the greatest divergence in regard to issue position. A discussion of these patterns offers insight into elite strategy and debate in the party period.

Polarization in the1850s

In addition to the increasing prominence of ethnocultural concerns, events such as the Mexican War, Compromise of 1850, and the bloody dispute in Kansas hastened the demise of the second-party system in the antebellum years by exacerbating sectional tensions over slavery and state autonomy (Foner Reference Foner1995; Gienapp Reference Gienapp1987; Holt Reference Holt1978; Potter, Reference Potter1976). Exploring how the parties marketed their message to the public enhances our understanding of this competitive system’s decline.

While the parties exhibited clear differences on the key issues of tariff protection and internal improvements, they offer more obfuscated references on slavery. Generally, the Democrats do not explicitly express their support for the peculiar institution, while the Whigs tend to oppose the expansion, and Republicans express their opposition to it.Footnote 13 The Democrats embrace a strict constructionist approach to the issue by arguing that Congress lacks the constitutional authority to regulate slavery within the territories and states. The Democratic position is more pronounced than the Whigs’ position, which reflects intraparty antagonisms. To reconcile the northern and southern wings of the party, Whigs, on the national level, usually endorse measures intended to stem the spread of slavery into territories where it does not exist. For example, in 1852, the national Whig platform attempts to declare the issue settled through an enforcement of the compromise measures of 1850 (table 2). The inclusion of a plank endorsing the Compromise of 1850 reflects the influence and fears of the Southern Whigs. Northern Whigs and supporters of the eventual presidential nominee, General Winfield Scott, sought to keep any mention of slavery or the Compromise out of the platform. Further, evidence suggests that Scott had no intention of taking a stand on these issues in his campaign (Gienapp Reference Gienapp1987: 18; Holt Reference Holt1999a: 699–701).

Table 2 Democratic and Whig statements on slavery in their national platforms of 1852

Source: Porter and Johnson Reference Porter and Johnson1961.

On the state level in 1852, a few southern affiliates supplement this position of the national party with a few planks opposing abolition. The Texas Whigs declare their support for the nominee of the national convention, “believing that that convention will be too honest to select as a candidate for the Presidency an abolitionist.” Their delegates are free to support the candidate of their choosing, as long as they do not “cast a vote for any man who they believe will consent to any repeal or modification of the present Fugitive Slave Law” (Winkler Reference Winkler1916: 53).Footnote 14 That said, like the rest of their southern brethren, the key issue for Texas Whigs was their support for the Compromise of 1850 (Holt Reference Holt1999b: 554–56, 632–34, 679–82, 717).

Regarding the compromise measures, both parties indicate a desire to reach some degree of agreement to maintain the status quo, or balance, in the years immediately preceding secession. This desire to achieve balance and keep the status quo is due in part to the burgeoning Republican Party, which affected coalitions on the state level. In 1856, the Indiana Democrats, facing a competitive statewide race from Republicans who were drawing support from Know Nothing and disaffected Whig partisans (Gienapp Reference Gienapp1987: 394–96, 401–3), declare their approval for “the principles of the compromise measure in 1850, and their application as embodied in the Kansas-Nebraska bill, and will faithfully maintain them” (Henry Reference Henry1902: 11). Similarly, the Virginia Whigs accuse the Republicans of being “wholly committed to a sectional issue, and engaged in a crusade against acknowledged constitutional rights and the Union of the States,” and declare that “having cordially accepted the compromises of 1850, as necessary concessions to conflicting views and interests; and being opposed to the renewal of the agitation of the questions to which those compromises relate, will now resist any repeal or modification of the Kansas-Nebraska act, as calculated to renew and inflame the strife that at this time endangers the rights and the Union of the States” (Richmond Whig and Public Advertiser 1856).

Overall, the parties offered divergent but nuanced positions on slavery. Because they did not offer opposing positions on each of the same slavery issues—one party presenting its staunch opposition or support, while the other party is either “neutral” or silent on that same issue—their message to the electorate may have been obfuscated, thus, contributing to the perception that the parties lacked significant differences on the major issues of the day.

The platform references to slavery reflect the difficulty in crafting a national electoral coalition. Holt (Reference Holt1982, Reference Holt1992) argues that the Whigs perceived their strength lay in their viable opposition to the Democrats. To accomplish this, in 1848, the Whigs devised a triparte plan that freed up state and local affiliates to run regional campaigns. In lieu of an official national platform, the party nominated a candidate with broad appeal, thus enabling elites to argue their case on ideological principles while appealing to regional concerns. Although immediately successful, this strategy proved unsuccessful in the long run. By 1852, the voters failed to perceive any substantive differences between the two parties primarily because they both endorsed the Compromise of 1850 in their national platforms. Moreover, the Whigs lost credibility among their base and suffered internal strife by reaching out to Catholic voters, and lost traction among the broader populace when the economic boom validated many of the Democratic policies (Gienapp Reference Gienapp1987: 20–27, 35; Holt Reference Holt1992: 244–51). The demise of the Whigs and subsequent rise of the Republicans further upset the sectional balance that had long been the overarching goal of the Democrats and Whigs (Weingast Reference Weingast1998).

Polarization in the 1890s

After 1876, the United States settled into a stable, competitive two-party system, which, in many ways, resembled the partisan warfare of the antebellum period (Silbey Reference Silbey1991: 216). This return of national party competition includes an increased level of party polarization on issue position, as well as a convergence on platform issue content. On key issues, such as the tariff, internal improvements, and Reconstruction measures, for the most part, the parties offered delineated contrasting positions. The tariff and internal improvements especially reflected ideological concerns but related to distributive policies or particularized interests more prominently. As a result, the cause for the debate between the parties on these issues were at times starker than others (Lee Reference Lee2016). On perhaps the most controversial economic issue of the Gilded Age, the standards debate, however, the parties converge for most of the period. It appears that neither party seemed to articulate an explicit stance on the matter until the 1890s due to the regional splits within both parties over the money question (Lee Reference Lee2016; Ritter Reference Ritter1997).

The 1896 election serves as the apex of polarization. The parties articulate divergent positions on the gold standard and free silver. Like slavery in the 1850s, the parties offer opposing positions on the standards question without explicitly referencing the same policy. For example, while it appears that the national parties are neutral or silent on the gold standard, this is not the case. The Democrats couch their opposition to monometallism (the gold standard) in terms of their support for bimetallism, which, according to them, is the free, unlimited coinage of silver (Porter and Johnson Reference Porter and Johnson1961). The Republicans, however, present their support for the gold standard in their critique of the free and unlimited coinage of silver. They do not oppose bimetallism, per se, so long as gold remains dominant and does not lose its value:

We are unalterably opposed to every measure calculated to debase our currency or impair the credit of our country. We are therefore opposed to the free coinage of silver, except by international agreement with the leading commercial nations of the earth…. All of our silver and paper currency must be maintained at parity with gold. (Porter and Johnson Reference Porter and Johnson1961)

The presence of the Populist Party in the 1890s helped to galvanize passions around the standards debate. Faced by external and internal pressures, the Democrats ultimately decided to adopt the free and unlimited coinage of silver as its core position in the 1896 campaign. The Republicans also faced internal pressure but successfully secured the support of the business community and maintained its traditional hard-money position (Martin Reference Martin2006).

The difference in the realignments of the 1850s and 1890s, measured by the relative success of the Republicans and Populists in their respective periods, may be due to a contrast in the competitive environments the two periods.Footnote 15 First, the overall party period is characterized by high voter turnout, which affected the competitive nature of these years. Local and state party agents contributed to this high turnout by mobilizing the electorate through rallies and other morale-boosting activities, as well as through more nefarious means such as bribery (Bensel Reference Bensel2004). In the presidential elections of 1840 through 1896, the percentage of eligible voters who voted hovered between 75 to 80 percent, except for 1852 in which the turnout was 69.5 percent. On the national level, the absolute difference in vote percentage between the two major parties in these same presidential elections averaged 5.5 percent, and if the elections immediately preceding and during the war are eliminated, the difference is less (Silbey Reference Silbey1991: 145).Footnote 16 The successful mobilization of voters by both parties helped create and maintain an intensely competitive system.

The antebellum years were highly competitive between the Democrats and Whigs. The 1840 election ushered in a period of more partisan cohesion in which the “national parties penetrated into the states” (Shade Reference Shade1981: 84). This competition declined with the disintegration of the second-party system in the mid-1850s. The chaotic environment of the years immediately preceding secession broke down the second-party system in favor of a more sectional system between the Democrats and nascent Republican Party right before the war, with a Whig Party and American Party attempting to carve out positions in between. At the war’s conclusion and after Reconstruction, the third-party system develops into a nationally competitive environment between the Democrats and Republicans.

The competition between the Democrats and Republicans in the Gilded Age differs from the antebellum period in that while parties were intensely competitive on the national level, they also tended to hold relatively stable majorities in many of the states.Footnote 17 In all, only about five to seven states were truly competitive. This national balance between the two parties was somewhat fragile, however, because it depended on the Democrats staying competitive in five states (Ware Reference Ware2006: 53–66).

Conclusion

An examination of state and national platforms of the Democratic and Whig/Republican parties from 1840 to 1896 reveals a party system in which the two main opposing parties presented alternative programs to the electorate. For most of the party period, the two parties offer the voting public a clear choice on the main issues of the day. From 1840 to 1852, the Democrats and Whigs presented divergent positions on the economy and on their view of the proper role and sphere of the general government. In the 1850s, the exacerbation of slavery and the rise of nativism and ethnocultural concerns disrupted the balance between these two parties.

The war years and their immediate aftermath depict a period of convergence because the war consumed practically the entire debate. In the north, the Democrats struggled to act as a loyal opposition party and the south lacked a party system altogether (Silbey Reference Silbey1977). The post- Reconstruction period experienced a reinvigorated competitive two-party system. The parties leaned on their past records and again offered conflicting stances on economic issues and on ideological ones involving the role of the state. Convergence in the Gilded Age is represented by the Democrats and Republicans neglecting to articulate clear stances on the monetary standard issue until the 1890s, at which time, they argue for opposing positions. Although the parties seemed not to offer competing policies at times, overall, they did embrace contrasting political programs throughout the bulk of the nineteenth century.

The question then is why the parties, which avoided articulating clear opposing positions on the two prominent issues of the respective periods—slavery in the antebellum years and the monetary standard in the Gilded Age—suddenly changed to offer divergent positions. The role of political elites offers a possible explanation.

Because platforms are primarily elite documents, determining the character of policy planks in these platforms should illuminate elite strategy. Party leaders may stipulate a clear stance on one issue and avoid another issue altogether. Noting when, and to what degree, party leaders address certain issues and not others helps clarify patterns of convergence and divergence between the two parties on the national and state levels, as well as on what issues sparked these patterns.

As the party system became less fragmented and more centered on the two main parties, the parties seemed to reach a level of consensus on which issues would be discussed in the platforms (Silbey Reference Silbey2001). Party elites help to shape the preferences of the masses by initiating policies (Pomper Reference Pomper1967: 318; Ware Reference Ware1996: 326–27). But, the occasional antagonism between party elites and masses constrains elite behavior as elites attempt to craft an appealing electoral message (Gerring Reference Gerring1998: 269–73; Gienapp Reference Gienapp1982: 52–53; Silbey Reference Silbey1991: 121–24). Add to this the reality of having to negotiate competing claims from the various state and local party organizations, and a climate develops in which national and state party leaders may prefer to address less controversial issues and address controversial issues only when necessary. Moreover, as the party system transitioned from the second into the third, national issues continued to dominate the debate between and within the parties (Bensel Reference Bensel2000: 178; Silbey Reference Silbey1991: 86–87). In presidential election years, most intraparty disputes and factional splits that occurred at party conventions in the second half of the nineteenth century were due to controversies over issues, such as party nominees and repayment of the state debt. Focusing on national issues enabled party leaders to reconcile these disputes. In the 1890s, however, the monetary question rose to prominence and became the main cause for most intraparty conflict (Bensel Reference Bensel2000: 101–11). To simultaneously cultivate a broad coalition and recognize regional and local concerns, state party organizations exercised a level of autonomy in how to present these issues to their constituents (Bensel Reference Bensel2000: xviii; Silbey Reference Silbey1991: 70–85). Elite electoral strategy and dominance of national issues in all levels of debate contributed to an environment in which the parties offered competing positions on these same or similar issues.

When the parties ceased to present stark divergent positions on issues, such as through their roll-call votes and in their platforms, the system fell apart. Questions about the degree of competition necessary to keep a two-party system intact, perceptions and strategies of party elites in the face of external threats, and the strength of organizations over time will guide future studies of nineteenth-century party development and, more broadly, of party systems and organizations.

Appendix

Appendix A: Platform Domain Codes

The economic domain includes platform planks articulating stances on issues relating to monetary and fiscal policy, such as the tariff, banking, pensions for veterans and their families, currency, taxation, payment of debt, retrenchment, and trusts and monopolies.

The culture domain encompasses policy proposals of the traditional ethnocultural literature, as well as proposals on Native American rights, women’s rights, and civil rights and liberties as stipulated in the Bill of Rights and are part of American political culture.

The government and political institutions domain highlights issues relating to the alteration of government institutions and procedures, such as election and campaign finance reform, the direct election of US senators, civil service reform, the judiciary, and government corruption.

The statism domain incorporates policy planks that address the role of the national government and its scope and power, or the ideological difference between positive and negative government. These planks include internal improvements, states’ rights, executive power, and limited government.

The labor domain consists of proposals addressing issues like references to prison labor, wages, hours and conditions, and child labor.

The foreign policy domain references territorial acquisition and expansion, military intervention, and provisions for the growth and development of the armed forces.

The slavery and black civil rights domain references slavery policy in the antebellum period, Reconstruction, and the subsequent treatment of the black population in the postbellum and post-Reconstruction America.

Appendix B: Content Analysis Methodology

Salience

Salience is measured in three steps: (1) count the total number of words referring to a specific issue, such as the protective tariff; (2) divide that number by the total coded number of words of that platform;Footnote 18 and (3) multiply that figure by 100 to get the salience score (formula for calculating salience: Issue Word Count/Total Coded Word Count×100). Next, to obtain the salience of each domain in a platform, the salience for each individual issue of that domain is summed up. For example, in the California Democratic platform of 1892, tariff protection accounts for 16.86 percent of the platform of the total coded text—Tariff Protection Word Count (327)/Total Platform Word Count (1939)×100 (Davis Reference Davis1893). References to other economic issues, such as antitrust and monopoly regulations and public land sales account for salience scores of 7.94 and 3.25, or about 8 percent and 3 percent of the platform, respectively. These three variable salience scores are summed with the salience scores of the rest of the economic issues referenced in the platform to get a total economic salience for this platform of 59.62. This same calculation is used to obtain the salience for each policy issue within the other domains.

Position

Position is recorded on a scale, in which –1 denotes opposition to the issue, 0 neutral or not mentioned, and +1 in favor. To further illustrate a party’s stance on the issue, position is combined with salience to devise a positional salience, which is reached by multiplying the issue salience by its position. For a neutral position, when multiplied by its salience, the positional salience will be 0, regardless of the issue’s salience. To take the previous example, the weighted salience of tariff protection in the California Democratic platform of 1892 is 16.86. The party takes a position opposing the policy (–1). Therefore, the positional salience of tariff protection in this platform is –16.86.

Variance

Variation around the mean can be depicted through the variance, or its square root—standard deviation. To gauge variation around the mean more accurately in this study, variance is taken as the weighted standard deviation, which is calculated by multiplying the standard deviation of an issue by its salience. The standard deviation is weighted to account for the relative salience of each of the domains. A minimally salient issue domain across the data set, such as labor, could skew the results if it was treated on an equal basis with a highly salient one, such as economics. Weighting the standard deviations by multiplying them with the salience attempts to minimize this problem. For example, the average salience of cultural issues across the entire data set in 1876 is 19.32. That is, in 1876, all parties across all the states, on average, devoted more than 19 percent of their platforms to references to cultural issues. The standard deviation is 16.03. The weighted standard deviation, or variance in this study, equals 309.65.