Introduction

Affective instability (AI) is widely described in the psychiatric literature but there is a lack of agreement and consistency in definitions (Westen et al. Reference Westen, Muderrisoglu, Fowler, Shedler and Koren1997; Links et al. Reference Links, Eynan, Heisel and Nisenbaum2008; Trull et al. Reference Trull, Solhan, Tragesser, Jahng, Wood, Piasecki and Watson2008). Definitions of AI incorporate frequent affective category shifts, disturbances in affect intensity, excessively rapid emotion rise times and delayed return to baseline, excessive reactivity to psychosocial cues and overdramatic affective expression (Koenigsberg, Reference Koenigsberg2010). The term is used interchangeably with mood instability, affective lability, affective and emotional dysregulation and mood swings, by researchers and clinicians alike. Operationalizing AI has proved difficult (MacKinnon & Pies, Reference MacKinnon and Pies2006), although statistical modelling and methods based on experience sampling applied in the short term (Ebner-Priemer et al. Reference Ebner-Priemer, Kuo, Kleindienst, Welch, Reisch, Reinhard, Lieb, Linehan and Bohus2007a , Reference Ebner-Priemer, Eid, Kleindienst, Stabenow and Trull2009) and longer term (Bonsall et al. Reference Bonsall, Wallace-Hadrill, Geddes, Goodwin and Holmes2012) have been suggested.

AI can be understood as a trait-like dimension or as a symptom profile representing a change from a pre-morbid state. As a trait and defined as ‘a marked reactivity of mood’ in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV; APA, 2000) as a borderline personality disorder (BLPD) criterion it has been estimated to have a general population prevalence of around 14% (Black et al. Reference Black, Blum, Letuchy, Carney Doebbeling, Forman-Hoffman and Doebbeling2006; Marwaha et al. Reference Marwaha, Parsons, Flanagan and Broome2013). It is also clinically important as prospective studies show that, of all the BLPD diagnostic criteria, AI is the strongest predictor of suicidal behaviour, exceeding negative mood state in its effect (Yen et al. Reference Yen, Shea, Sanislow, Grilo, Skodol, Gunderson, McGlashan, Zanarini and Morey2004). Neuroticism (Korten et al. Reference Korten, Comijs, Lamers and Penninx2012) and having more interpersonal difficulties with partners are both associated with AI as well as future depression (Miller & Pilkonis, Reference Miller and Pilkonis2006; Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Berenbaum and Bredemeier2011).

A very strong and consistent association between AI and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has been shown. It has been argued that AI should be a diagnostic criterion for ADHD, given its high prevalence in this disorder and the overlapping neurobiological and cognitive features of those with AI and ADHD (Skirrow et al. Reference Skirrow, McLoughlin, Kuntsi and Asherson2009). There is also evidence of a diminution of AI when present in ADHD in response to stimulant therapeutic agents both in children (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Hermens, Palmer, Kohn, Clarke, Keage, Clark and Gordon2008) and adults (Reimherr et al. Reference Reimherr, Williams, Strong, Mestas, Soni and Marchant2007).

The clinical significance of AI extends outside of disorders in which it is understood as a trait. If conceptualized as a symptom profile, AI encompasses a wide range of mental disorders. In a prospective follow-up of army conscripts, cyclothymia (which was defined mainly as higher levels of AI) was a very significant predictor of transition to future bipolar disorder, increasing the odds greatly, and having a larger effect than for family history of the illness (Angst et al. Reference Angst, Gamma and Endrass2003). Because of its importance it is considered a target for treatment in its own right in bipolar disorder (Henry et al. Reference Henry, Van den Bulke, Bellivier, Roy, Swendsen, M'Bailara, Siever and Leboyer2008a ). AI is also frequent in depression (Bowen et al. Reference Bowen, Mahmood, Milani and Baetz2011b ) and anxiety disorders (Bowen et al. Reference Bowen, Clark and Baetz2004). Though present in varied psychiatric disorders, it is uncertain whether what is being measured is the same or discrepant and this may lead to diagnostic confusion.

The imprecision and lack of clarity about this phenomenological construct, how the terms used to describe it are defined and the reliability and validity of the measures employed all combine to limit empirical research about AI and its clinical application. Our study objectives were to answer two main questions:

-

(a) What are the definitions of AI in clinical populations, in the scientific literature?

-

(b) What are the available measures of AI and how reliable and valid are these?

Method

We conducted a systematic review of the literature and use the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Grp2009) in this paper to describe our procedures and results.

Information sources

MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, PsycArticles and Web of Science bibliographic databases were searched from their date of inception to February 2012. Reference lists of included studies were searched for relevant citations. In all, five journals were hand searched spanning the previous 5 years (from June 2007 to June 2012). These were: the American Journal of Psychiatry, Psychological Medicine, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, Journal of Affective Disorders and Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. These journals were those considered most likely to yield relevant papers after a scoping run of our search strategy.

Search

The research team discussed and reviewed the results of an initial scoping search. We developed a strategy using five groups of search terms. These were: AI, affective dysregulation, affective lability (group 1); mood instability, mood dysregulation, mood lability, mood swings (group 2); emotion instability, emotion dysregulation, emotion lability (group 3); BLPD, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), unstable personality traits (group 4); and Mood Disorder Questionnaire (Hirschfeld et al. Reference Hirschfeld, Williams, Spitzer, Calabrese, Flynn, Keck, Lewis, McElroy, Post, Rapport, Russell, Sachs and Zajecka2000), the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Sharp et al. Reference Sharp, Goodyer and Croudace2006), Affective Lability Scale (ALS) (Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, Greenberg and Serper1989), Affective Intensity Measure (AIM) (Larsen et al. Reference Larsen, Diener and Emmons1986), Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, Reference Goodman1997), the Child Behaviour Checklist (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991) (group 5). Cyclothymia was included in the search as a medical subject heading (MESH) term. The search was augmented in April 2013 by adding attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as a specific term (in group 4).

In summary, the strategy was to include all relevant abstracts relating to groups 1, 2, 3 AND group 4, and groups 1, 2, 3 AND group 5. Terms were adapted as necessary for other databases. The exact search strategy and full list of terms as they were entered into MedlinE are shown in online Supplementary Fig. S1. Results were downloaded into ENDNOTE X5 (Thomson Reuters, USA). The search included reviews and primary studies. If a previous review was found, we searched the reference list to identify and retrieve the primary studies.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

-

(a) Study design: experimental studies [randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized controlled], controlled before-and-after studies, controlled observational studies (cohort and case–control studies) and epidemiological investigations.

-

(b) Comparison: we did not apply restrictions for comparison groups.

-

(c) Participants: were adults over 18 years old and were defined as having a mental disorder if they met criteria as defined in the DSM-IV or International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10.

-

(d) Definition: any definition of the AI term was provided.

-

(e) Measures: were defined as any assessments of AI including any paper-and-pencil or computer-administered questionnaires or measures based on structured interviews.

Excluded studies were:

-

(a) case reports;

-

(b) non-English-language papers;

-

(c) cross-cultural language validation studies;

-

(d) studies sampling people with organic disorders (e.g. brain injury, tumour, dementia, etc.).

Abstract screening

More than 11 000 abstracts were retrieved using our search strategy (n = 11 443). If a title appeared potentially eligible but no abstract was available, the full-text article was retrieved. One researcher (Z.H.) scanned all titles and abstracts to identify relevant articles for full-text retrieval. Another researcher (J.E.) independently assessed 50% of the abstracts to identify relevant articles. There was high level of agreement (80%) between raters. Any disagreements were referred to a third researcher (S.M. or M.B.) and then resolved by consensus.

Data collection process and assessment of quality

Data on study design, participants, definition and measurements were extracted from full-text papers. Types of bias assessed in individual studies were selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias and other bias as suggested by the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins & Green, Reference Higgins and Green2011). Any uncertainties were referred to others in the study team for resolution.

Synthesis of results

In order to synthesize the very large number of abstracts generated by our search we partitioned the abstracts into three groups; those that focused on measures in adults, in children and neurobiological measures. This paper addresses AI definitions and measures in the adult clinical populations. The included studies were heterogeneous in terms of definition and measurement of AI; hence we report a narrative synthesis of the findings. For each assessment scale we identified psychometric properties from the relevant paper or from the wider literature.

Results

Study selection

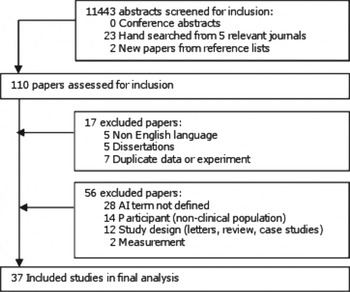

The PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1) shows the process of identification and selection of papers. A total of 110 full-text articles were assessed, of which 73 were excluded. The most common reasons for exclusion were because the publication did not provide a definition of AI or did not include a clinical subpopulation in the sample.

Fig. 1. PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart.

Study characteristics

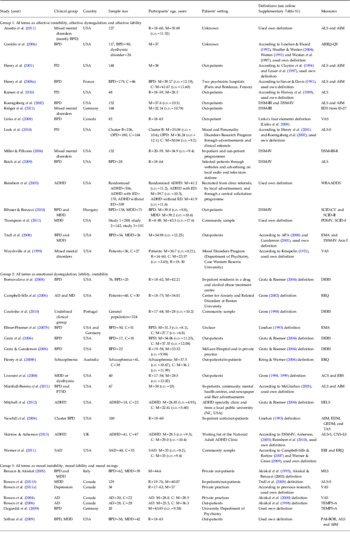

In all, 37 primary studies were identified for final analysis. There were two RCTs and 35 non-randomized experimental design studies. There were no family or twin studies in the included papers. Further characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 1. Included studies were conducted in the USA, Europe, Canada or Australia. The sample size ranged from 20 to 1065, whilst the age range of participants included adults up to the age of 89 years old. One study included children as young as 8 years old but as the sample also included adults and the mean age of participants was 43.5 years (Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Berenbaum and Bredemeier2011) this study met our criteria for inclusion. The clinical groups included patients with anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, mood disorders, personality disorder, PTSD, social anxiety disorder, ADHD and schizophrenia.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies (n = 37)

AI, Affective instability; BPD, bipolar disorder; R, age range; M, mean age; s.d., standard deviation; ALS, Affective Lability Scale; AIM, Affective Intensity Measure; AREQ-QV, Affect Regulation and Experience Q-sort-Questionnaire Version; PD, personality disorder; C, control group; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; EDS, Emotion Dysregulation Scale; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; OPD, other personality disorder; ALS-S, Affective Lability Scale Short Form; DSM-III-R, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition, revised; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; ED, emotional dysregulated; WRAADDS, Wender–Reimherr Adult Attention Deficit Disorder Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; SCID-CV, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV clinician version; SCID-II, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders; PDI-IV, Personality Disorder Interview-IV; SCID-I, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders; EMA, Ecological Momentary Assessment; DERS, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; AD, anxiety disorders; MD, mood disorders; REQ, Responses to Emotions Questionnaire; ERQ, Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; ACS, Affective Control Scale; ERS, Emotion Regulation Scale; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; I/ELS, Impulsivity/Emotional Lability Scale; EDM, Emotion Dysregulation Measure; GEDM, General Emotional Dysregulation Measure; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; CNS-LS, Centre for Neurologic Study-Lability Scale; SAD, social anxiety disorder; ERI, Emotion Regulation Interview; MLS, Mood Lability Scale; TEMPS-A, Temperament Evaluation of the Memphis, Pisa, Paris, and San Diego Auto Questionnaire; PAI-BOR, Personality Assessment Inventory – Borderline Features Scale.

Definitions of AI terms

Definitions of AI terms are listed in online Supplementary Table S1, with references to the key studies that used them. Numbers of different definitions were: AI (n = 7), affective lability (n = 6), affective dysregulation (n = 1), emotional dysregulation (n = 4), emotion regulation (n = 2), emotional lability (n = 1), mood instability (n = 2), mood lability (n = 1) and mood swings (n = 1).

The definitions for AI terms frequently emphasized significant fluctuations in affect and the intensity of these changes as core features. They were discrepant in whether negative mood was given special prominence, the extent of clinically significant impairment and/or whether environmental triggers were a necessary precipitant of change in affect. Exact information about the time period over which the affect lasted and the frequency of change were absent in the vast majority of definitions, though descriptors such as ‘frequent’ or ‘rapid’ were used in some. Three definitions specified the frequency of affect change as lasting over a few hours and rarely more than a few days.

There did not appear to be relevant differences between the AI definitions specifically and those for affective lability or dysregulation, mood instability, lability or mood swings. However, there was a lack of consistency in the number of facets (e.g. frequency, intensity) that were described or required in definitions of mood instability, lability or swings. Though the terms mood and affect were frequently used interchangeably in studies, mood is usually defined as a sustained emotional state (Wing et al. Reference Wing, Cooper and Sartorius1974).

There was also a considerable overlap between the definitions for emotional dysregulation and those for dysregulation (e.g. lability, instability) of mood and affect. For example, a number of studies purportedly focused on AI incorporating intensity, lability and regulation but in the text went on to define the term emotional dysregulation (Yen et al. Reference Yen, Zlotnick and Costello2002; Conklin et al. Reference Conklin, Bradley and Westen2006; Marshall-Berenz et al. Reference Marshall-Berenz, Morrison, Schumacher and Coffey2011). On the other hand, some publications that were concerned with investigating emotional dysregulation actually defined and measured what they described as AI in the text (Kröger et al. Reference Kröger, Vonau, Kliem and Kosfelder2011). One possible difference between definitions of emotional dysregulation compared with other search terms was the emphasis placed on the subjective lack of capacity to regulate or control affect and its behavioural sequelae.

The key features within the definitions of AI terms, in the main, were not disorder specific. For example, the term emotional lability used in the ADHD literature is defined as irritable moods with volatile and changeable emotions (Asherson, Reference Asherson2005; Skirrow & Asherson, Reference Skirrow and Asherson2013). This shared the characteristics of the term affective lability defined as rapid shifts in outward emotional expressions (Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, Greenberg and Serper1989) used in the context of BLPD and bipolar disorder.

We refer to AI as the main comparison term from this point onwards, as this label had the greatest number of definitions and many of the papers discussing the other terms listed in online Supplementary Table S1 also referred to AI as an overarching term.

Measures of AI

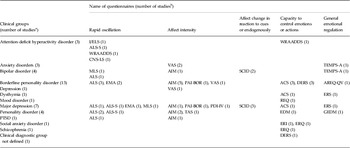

A total of 24 measures are used to assess constructs labelled by various combinations of the words affective, mood, emotion, instability, lability, swings and dysregulation, with the majority being self-report. These are shown in Table 2 alongside the available psychometric data; more details are given in online Supplementary Table S2. Reliability assessments (using Cronbach's α) were available for most measures. These indicated moderate to excellent levels of internal consistency, with α values ranging from about 0.6 to 0.9. Test–retest, inter-rater reliability and validity assessments were uncommon. Some measures had no psychometric evaluation and these tended to be either bespoke instruments involving a few questions (e.g. Mood Lability Scale; Akiskal et al. Reference Akiskal, Maser, Zeller, Endicott, Coryell, Keller, Warshaw, Clayton and Goodwin1995) or one or two items related to AI extracted from interview assessments such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID).

Table 2. Questionnaires (n = 24) used in the included studies a

IC, Internal consistency.

a For detailed information, please see online Supplementary Table S2, which includes descriptions of the questionnaires, and their reliability and validity.

Online Supplementary Table S3 shows the different aspects of AI that were primarily addressed by each measure. These were rapid oscillations in affect, extent of affect intensity, the degree to which changes were endogenous or in response to cues, and the subjective capacity to regulate/control affect or behavioural sequelae. The measures that assessed this last component included items such as non-acceptance of negative emotions, inability to engage in goal-directed and non-impulsive behaviour when experiencing negative emotions, limited access to emotion-regulation strategies (e.g. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; DERS) and emotional suppression and cognitive reappraisal (e.g. Emotion Regulation Questionnaire).

There were also other assessment scales such as the General Emotional Dysregulation Measure (Newhill et al. Reference Newhill, Mulvey and Pilkonis2004) that were broader in their scope and appeared to measure general emotional regulation. No measure primarily assessed emotional rise times and delayed return from heightened arousal, although these aspects were included as single items in some of the measures found.

AI measures and their use in different clinical groups

Table 3 shows which measures have been used in different mental disorders arranged according to the main aspects of AI purportedly assessed. Whilst AI has been measured in a wide range of mental disorders, those with BLPD and major depression were the most frequently sampled. For BLPD, measures have primarily assessed oscillation in affect, affect intensity and the capacity to control emotions and actions. The AIM was the most commonly used in this disorder, followed by the ALS and the Affective Control Scale (ACS; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Chambless and Ahrens1997). The ALS and AIM were also commonly used to measure AI in studies focusing on other personality disorders.

Table 3. Clinical groups and AI questionnaires

AI, Affective instability; I/ELS, Impulsivity/Emotional Lability Scale; ALS-S, Affective Lability Scale Short Form; WRAADDS, Wender–Reimherr Adult Attention Deficit Disorder Scale; CNS-LS, Centre for Neurologic Study-Lability Scale; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; TEMPS-A, Temperament Evaluation of the Memphis, Pisa, Paris, and San Diego Auto Questionnaire; MLS, Mood Lability Scale; ALS, Affective Lability Scale; AIM, Affective Intensity Measure; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; EMA, Ecological Momentary Assessment; PAI-BOR, Personality Assessment Inventory – Borderline Features Scale; ACS, Affective Control Scale; DERS, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; AREQ-QV, Affect Regulation and Exp0erience Q-sort-Questionnaire; ERS, Emotion Regulation Scale; REQ, Responses to Emotions Questionnaire; EMA, Ecological Momentary Assessment; PDI-IV, Personality Disorder Interview-IV; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; EDM, Emotion Dysregulation Measure; GEDM, General Emotional Dysregulation Measure; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; ERI, Emotion Regulation Interview; ERQ, Emotion Regulation Questionnaire.

a Number of included studies that were conducted in certain clinical groups. b Number of included studies that used the questionnaire for this clinical group.

A total of 10 studies focused on depressive disorder, with no real preponderance of a particular set of measures, and covered all aspects of AI as well as general emotional regulation. AI using the measures identified has been rarely investigated in bipolar disorder. There were three studies that sampled people with ADHD and used four different measures, only one of which (ALS) has been used in other diagnostic groups. Apart from this, no clear pattern emerged in terms of particular AI measures being preferred in particular disorders, with most having being used in at least three different mental disorders whether as measures of trait or state AI.

Risk of bias within primary studies

Only two included studies were RCTs (Reimherr et al. Reference Reimherr, Marchant, Strong, Hedges, Adler, Spencer, West and Soni2005; Conklin et al. Reference Conklin, Bradley and Westen2006), but the risk of selection bias was judged to be unclear as insufficient information was provided on random sequence generation and allocation concealment to allow an assessment of risk. All non-RCTs were judged to be at high risk of selection biases. The performance bias and detection bias were judged to be high in all included studies as participants could not be blinded to group allocation by the nature of the self-reported outcomes. The risk of attrition bias and outcome reporting bias were judged to be low in all studies.

Discussion

As far as we are aware this is the first systematic review of this subject in adult clinical populations.

Conceptualization of AI

The distinction between affective states in personality disorders which are described as traits and such disturbances in other mental disorders described as symptoms is largely artificial and their delineation is far from clear. When AI is described as a trait, part of this characterization relies on the assumption that AI is somehow inherent and stably expressed over time. However, the stability of a BLPD diagnosis over 2 years is 20–40%, with AI being one of the least stable features (Garnet et al. Reference Garnet, Levy, Mattanah, Edell and McGlashan1994; Chanen et al. Reference Chanen, Jackson, McGorry, Allot, Clarkson and Yuen2004). Longer-term stability is far less clear. AI also has trait-like properties in ADHD, a neurodevelopmental disorder. The fact that ADHD and BPLD co-occur (Faraone et al. Reference Faraone, Biederman, Spencer, Wilens, Seidman, Mick and Doyle2000) and both groups have difficulties with affect regulation makes differential diagnosis difficult and further clouds the issue of the specificity of AI being a trait of personality.

Considering AI to be purely a symptom does not sit neatly with findings suggesting that levels of AI are relatively high in people with bipolar disorder even in the absence of syndromal depression or elation (Bonsall et al. Reference Bonsall, Wallace-Hadrill, Geddes, Goodwin and Holmes2012). Also the frequency of affective fluctuation in bipolar spectrum disorders may be so large as to resemble that in BLPD (MacKinnon & Pies, Reference MacKinnon and Pies2006). These findings suggest that conceptualizations of AI as being a trait or symptom are not wholly mutually exclusive and neither does this dichotomous framework fully explain empirical findings.

Interestingly, the vast bulk of definitions that we found were not specifically linked with conceptualizing AI within a particular theoretical framework. There were three exceptions to this, two of which framed AI as a trait (Benazzi & Akiskal, Reference Benazzi and Akiskal2005; Ozgurdal et al. Reference Ozgurdal, van Haren, Hauser, Strohle, Bauer, Assion and Juckel2009) and a further definition suggesting affective lability was particularly relevant to both BLPD and bipolar spectrum disorders (Look et al. Reference Look, Flory, Harvey and Siever2010). This lack of specificity between theoretical framework and definitions and the associated measures means that AI is not only poorly understood but the use of different measures is not contingent on framing AI as a trait or symptom.

Definition of AI

The terms affective, mood or emotional instability, lability or regulation are used interchangeably because they are largely defined by similar attributes. One possible higher-level difference in definitions incorporating emotional and affective or mood terms is that the former mainly emphasizes the capacity to regulate affect, whereas the latter prioritizes the change of affect itself. The measures assess four core attributes. These are rapid oscillation and intensity of affect, a subjective sense of the capacity to control affect and its behavioural consequences and whether affect change is triggered in response to the environment or not. Examples of behavioural consequences of affective change in measures are ‘auto-aggression’, ability to engage in non-impulsive behaviours, and fears of becoming violent if furious. These four attributes of AI in measures also reflect commonalities within the definitions that were identified.

Our analysis indicates that AI as it is defined and measured is a broad concept. We propose a definition of AI that incorporates the three core elements of oscillation, intensity and subjective ability to regulate affect and its behavioural consequences. Thus AI is defined as ‘rapid oscillations of intense affect, with a difficulty in regulating these oscillations or their behavioural consequences’. The proposed definition would enable much of the varied lexicon in this area to be absorbed into the single term AI and has the advantage of not being reliant on a specific theoretical framework.

Definitions and measures were not clear about whether the affective changes are always in response to environmental cues and therefore we have not included this as part of our definition. Whether there is an environmental trigger may be disorder specific. The time-frame over which fluctuations of affect occur was usually absent in the reviewed definitions and therefore this also is not specified in our definition. We have excluded broader problems in emotional functioning from our definition because of its imprecision. A combination of current measures will be required to assess AI comprehensively if our definition is applied.

Evaluation of measures

Given the definition that we have proposed, a number of the measures identified should be preferentially used in assessing AI. There were two measures specifically assessing rapid oscillation of affect. The ALS (Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, Greenberg and Serper1989) has good internal consistency and is also the most frequently used measure in this area by far, having been used in all clinical diagnostic groups apart from schizophrenia and anxiety disorders. The Emotion Dysregulation Scale (Kröger et al. Reference Kröger, Vonau, Kliem and Kosfelder2011) also has good internal consistency; however, the scale focuses on affect dysregulation as well as impulsivity found in BLPD specifically and therefore the ALS may be more generally applicable. In terms of affect intensity, the AIM (Larsen et al. Reference Larsen, Diener and Emmons1986) is a self-report measure demonstrating good internal consistency, test–retest reliability and also construct validity.

The third element of our proposed definition of AI is the capacity to regulate affect or its behavioural consequences. Whilst the DERS is comprehensive and has strong psychometric properties (Gratz & Gunderson, Reference Gratz and Gunderson2006), it is limited by the items only referring to feeling low or upset. In comparison, the ACS (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Chambless and Ahrens1997) assesses regulation difficulties in a range of affect states (including happiness) and also has very good reliability and construct validity (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Chambless and Ahrens1997; Berg et al. Reference Berg, Shapiro, Chambless and Ahrens1998).

The assessment of available measures suggests that one possible scientifically useful way (though there may be others) to measure AI would be to use the ALS, AIM and the ACS in combination. However, further validation of this approach is required, in part because studies that have used the ALS and AIM in bipolar disorder (Henry et al. Reference Henry, Van den Bulke, Bellivier, Roy, Swendsen, M'Bailara, Siever and Leboyer2008a ) and BLPD populations (Koenigsberg et al. Reference Koenigsberg, Harvey, Mitropoulou, Schmeidler, New, Goodman, Silverman, Serby, Schopick and Siever2002) indicate that whilst both measures provide useful complimentary information, their scores are not independent of each other. Second, studies using Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) to measure real-time experiences of affect intensity and change suggest only modest levels of correlation, at best, between EMA and measures such as the ALS and AIM (Solhan et al. Reference Solhan, Trull, Jahng and Wood2009).

Measures of AI and clinical disorders

The ALS is commonly used in BLPD in particular. Three measures used in studies sampling ADHD were not used in other mental disorders. The Impulsivity/Emotional Lability Scale and the Centre for Neurologic Study-Lability Scale (CNS-LS) primarily measure fluctuation in affect, as does the relevant subscale of the Wender–Reimherr Adult Attention Deficit Disorder Scale (WRAADDS). However the questions used to assess AI in these measures as well as the definitions of AI terms from the ADHD and BLPD literature did not markedly differ in their quality and nature from those used in other clinical disorders.

Therefore, apart from a few exceptions, no clear pattern emerged in terms of preference for individual scales of AI in different disorders. These findings can be interpreted in a number of ways. First, it indicates that no overall ‘gold standard’ for measurement exists so far. This in turn is likely to be a reflection of the level of scientific knowledge about the phenomenological construct, which will need to explain whether AI is the same in different psychiatric disorders. One possible explanatory framework for the lack of specificity of particular measures and individual mental disorders is that AI, as it is currently understood, is on the continuum from trait to psychopathology.

This framework is supported by our results in that a wide range of AI definitions was listed in the literature. Also AI is present very early in the course of a number of major mental disorders including bipolar disorder (Howes et al. Reference Howes, Lim, Theologos, Yung, Goodwin and McGuire2011), BLPD (Zanarini et al. Reference Zanarini, Horwood, Wolke, Waylen, Fitzmaurice and Grant2011; Wolke et al. Reference Wolke, Schreier, Zanarini and Winsper2012) and major depression, suggesting that there is some differentiation over time from a non-specific symptom to disorder. Furthermore, this would be consistent with preliminary comparison studies of the extent of oscillation and intensity of affect in bipolar disorder and BLPD, which suggest similarities but also a range of subtle differences (Henry et al. Reference Henry, Mitropoulou, New, Koenigsberg, Silverman and Siever2001). Having a definition and measure of AI opens the opportunity to study how a predisposition for AI interacts with other factors to lead to a range of affect-related disorders.

The AI measures currently available have been most frequently used in the assessment of BLPD. They have the potential for utility in clinical practice to help mental health professionals understand the extent of symptomatology in BLPD, given the good psychometric properties observed. It is unclear whether they can be used in intervention research studies, given that we found none that were proven to be sensitive to change. In the ADHD context, the measures appear to have been used to understand AI in this disorder (e.g. CNS-LS) and also to assess change in treatment trials (e.g. WRAADDS) but their utility in routine clinical practice remains to be seen. Without further studies the measures cannot be recommended for routine clinical use in people with mood disorders, as there is a paucity of validation studies in mood disorders in comparison with BLPD.

Limitations

The current review only included reports in the English language and as such there may be other measures or definitions of AI that were not considered. Similarly, papers that sampled non-clinical populations were excluded and our conclusions may not be applicable to that group. We did not use the search term ‘emotional impulsiveness’. This is a term primarily linked to the ADHD literature, with the term being defined as ‘the quickness or speed with which and the greater likelihood that an individual with ADHD will react with negative emotions in response to events relative to others of the same developmental age’ (Barkley & Murphy, Reference Barkley and Murphy2010). Its omission was consistent with our strategy of neutrality with regards to the conceptualization of AI. There is also overlap between this term and emotional dysregulation which we did include (Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Robertson, Anastopolous, Nelson-Gray and Kollins2012).

All measurements of AI were related to current mental state but there was a lack of clarity about severity or phase of the clinical disorder being sampled in the primary studies. Patient populations were sampled from a broad range of settings (community, out-patients, in-patients, partial hospitalization) but it was uncommon to find a clear description of whether these were general or specialist services. Therefore we cannot comment on whether the current evidence base in biased in this respect.

There is likely to be a bias in the scientific literature on AI based on diagnosis. That is, whilst AI can occur in a range of mental disorders it is a diagnostic criterion for BLPD and therefore researchers are likely to have focused on this disorder. This bias was borne out in our review.

Implications for future research

Our clear and reproducible definition of AI has a number of potential implications for future research and the understanding of the development of a range of mental disorders. First, it has been argued that for inclusion in the DSM-5 a mental disorder should have proven psychobiological disruption (Stein et al. Reference Stein, Phillips, Bolton, Fulford, Sadler and Kendler2010). AI appears important in the pathway to a number of mental disorders as well as in established illness, and consistent definition and measurement open up opportunities to assess alterations in brain activity and other physiological systems. Our current understanding suggests that AI conceptualized as a trait may be influenced by genetic components representing emotional intensity and reactivity (Livesley & Jang, Reference Livesley and Jang2008). Future studies are required to address whether AI occurs as a syndrome in any specific neurological or genetic disorders.

Second, no single measure assesses all core elements of AI. There is clear scope for the development and psychometric evaluation of a measure of AI that assesses rapid oscillations of affect, intensity of affective change and subjective capacity to regulate affect and is short, reliable and validated against external criteria. Other than developing a completely new instrument, this could be achieved by factor analysis of responses to the recommended measures above.

Alongside the need to develop a single measure of AI that covers all its core elements it is necessary to more thoroughly understand the time-dependent nature of instability in order to further refine our definition. The most effective way of doing this would be to use EMAs of mood that can enable a prospective assessment of moment-to-moment changes in affect, avoiding retrospective recall bias. Knowledge of time-frames over which fluctuations occur could then be embedded into less labour-intensive methods of assessment. Third, clarification is necessary on the extent to which affective shifts and their duration reflect endogenous changes or occur in response to environmental stimuli and what these are, whether they cause clinically significant impairment in functioning or mental state and whether negative emotions should be given special prominence as is suggested by a number of researchers.

Fourth, further research should examine if the form of AI is similar across the full range of mental disorders in which it occurs or whether disorder-specific characteristics of AI exist. Case–control studies are needed in which AI is assessed in different mental disorders using the same measurement methods. These should especially focus in particular on bipolar disorder, depression and psychosis, as currently little is known about the characteristics of AI in these disorders. Finally, longitudinal studies are necessary to examine the expression and possible differentiation of AI over time, including through the developmental stage, and how environmental influences may put individuals on different AI trajectories. This will enable insights into whether AI has particular relevance to certain conditions or is simply a general outcome of abnormal psychopathology.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713002407.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by a grant from the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN) UK, Heart of England Hub.

Declaration of Interest

None.