Introduction

Logboats, also referred to as dugout boats, are vessels made of a single tree trunk. They were, and still are in some parts of the world, used for transportation, traveling, and fishing (Erič Reference Erič2014). Ancient logboats are usually found in wetlands, such as bogs, rivers, and lakes. The total number of logboats discovered in Europe exceeds 3000, and the oldest vessels date as far back as the Mesolithic (ca. 8000–7000 cal BC) (McGrail Reference McGrail1987; Arnold Reference Arnold2002).

In Lithuania logboats have been continuously manufactured and used for fishing in rivers and lakes from the end of the Subneolithic (= ceramic Mesolithic; ca. 4500–2900) until the middle of 20th century AD despite more advanced and complex watercraft made of wooden planks being available (Piškinaitė-Kazlauskienė Reference Piškinaitė-Kazlauskienė1998; Perminas Reference Perminas2008). There was a small gap of only a few decades between the construction of traditional logboats for fishing and transportation and the construction of modern logboats, used mainly for recreation or during scientific experiments. Lithuanian logboats from the more recent period can typically be found on the farmsteads of their users or in regional museums, where they have been transported from local river banks and lake shores. Such boats were in use during the 19th and/or 20th centuries, and sometimes even the names of their builders are known. More ancient boats are found during excavations or lying in the beds of modern rivers and lakes, while their chronology cannot be determined without 14C dating. In this paper we will focus on the older group of boats, using the term ancient to more broadly distinguish these vessels from those of the late modern period.

In 2015 an oak logboat (Quercus sp.) was discovered during testpitting at Šventoji 58, which is situated in coastal Lithuania. After an extensive 14C dating of the vessel and its context, it appeared that this dugout boat was constructed during the Neolithic, between 2895–2640 cal BC. Today the Šventoji 58 logboat is the first nearly complete Stone Age vessel that has ever been found in both Lithuania and in the entire Eastern Baltic, including Finland, Estonia, and Latvia. This new find, together with a general scarcity of Stone Age logboats in the East Baltic, encouraged us to review ancient logboat finds in Lithuania, to date them by 14C, and to identify the wood taxa that were used in their construction. We hope that our data, when combined with logboat studies from other regions (e.g. McGrail Reference McGrail1987; Ossowski Reference Ossowski1999; Lanting Reference Lanting2000; Pazdur et al. Reference Pazdur, Krapiec, Michczynski and Ossowski2001; Klooss and Lübke Reference Klooss and Lübke2006; Martinalli and Cherkinsky Reference Martinalli and Cherkinsky2009 etc.), will help contribute considerably to the understanding of the spread and production of logboats in Europe.

Methods

Radiocarbon (14C) dating of the wood samples was undertaken at 4 laboratories: the Poznań Radiocarbon Laboratory (Poland), the 14Chrono Centre for Climate, the Environment and Chronology, Queen’s University Belfast (UK), the Centre for Physical Sciences and Technology in Vilnius (Lithuania) and the Laboratory of Nuclear Geophysics and Radioecology, Nature Research Centre in Vilnius (Lithuania). The first three labs conducted 14C dating using accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) methods, while the fourth lab conducted its analysis with liquid scintillation counting (LSC) methods. The standard acid-alkali-acid (AAA) pretreatment protocol was used by all labs. In one case (Plateliai, dugout 1), when conservation materials (PEG) were suspected, the wood sample was additionally treated with ethanol before dating was undertaken. In this study all 14C dates were calibrated using the OxCal 4.2 software and IntCal13 atmospheric curve (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard and Bayliss2013). Calibrated dates are presented at 95.4% probability.

Wood taxa were identified by analyzing thin sections with an aid of bright-field microscope Optica B-193, between 40 and 1000× magnification. The evaluation of wood anatomical features and identification of taxa was based on Wheeler (Reference Wheeler2011) and Schoch et al. (Reference Schoch, Heller, Schweingruber and Kienast2004).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

General Information on Logboats in Lithuania

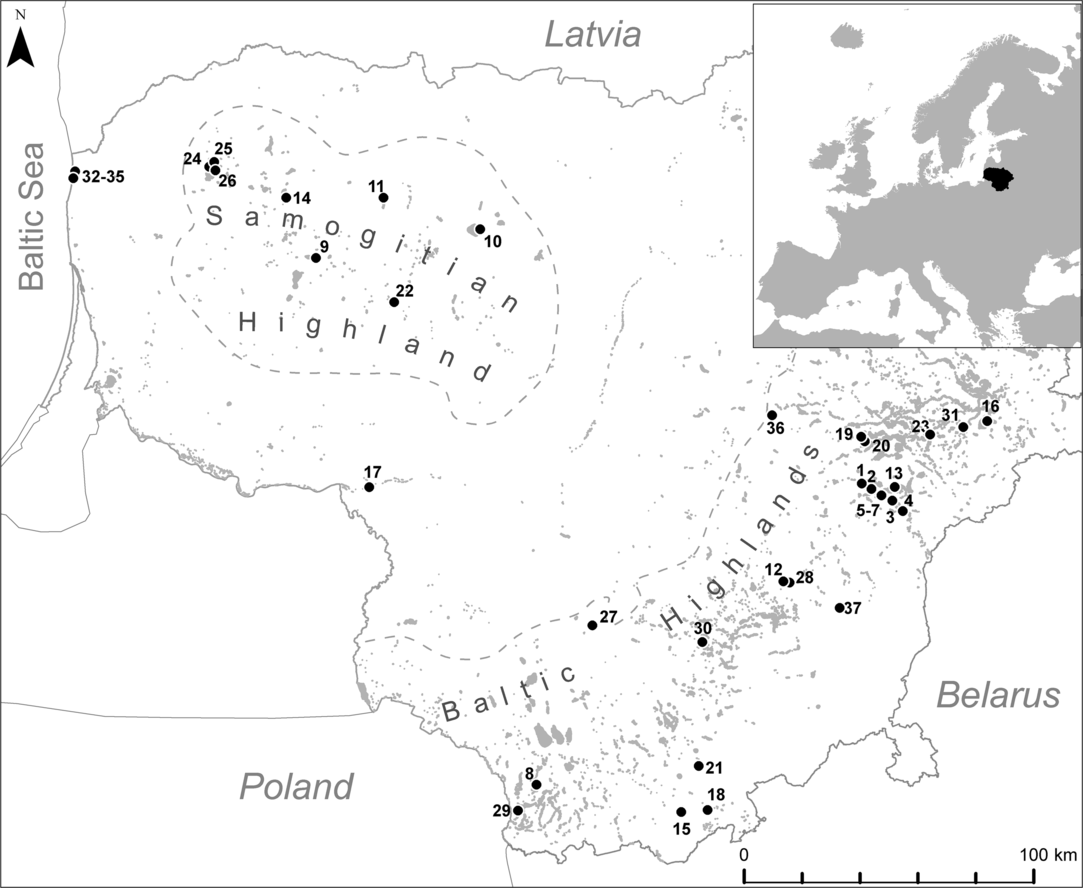

More than 70 logboats have been discovered in Lithuania and about half of them date to the earlier period before 1800 AD. These were discovered mostly by accident, lying in the beds of modern or ancient lakes and rivers. The highest density of ancient logboats finds is therefore in lake regions, such as the Samogitian and Baltic Highlands (Figure 1). Sixteen logboats were found during underwater surveys carried out by both archaeologists and recreational divers, and 12 of these vessels are still lying in situ at the bottom of those lakes and rivers. Seven logboats were found during various excavations at peatbogs. Logboats survived to present-day because they were preserved under anaerobic conditions. The ones that were excavated from these sites are currently owned by various state museums or private owners. Information about the circumstances in which they were found, the main morphological features, wood taxa, and the dating of ancient logboats found on the territory of present-day Lithuania are presented in a Table 1.

Figure 1 Ancient logboat finds in Lithuania. Lakes are indicated in grey, and the site names are provided in Table 1.

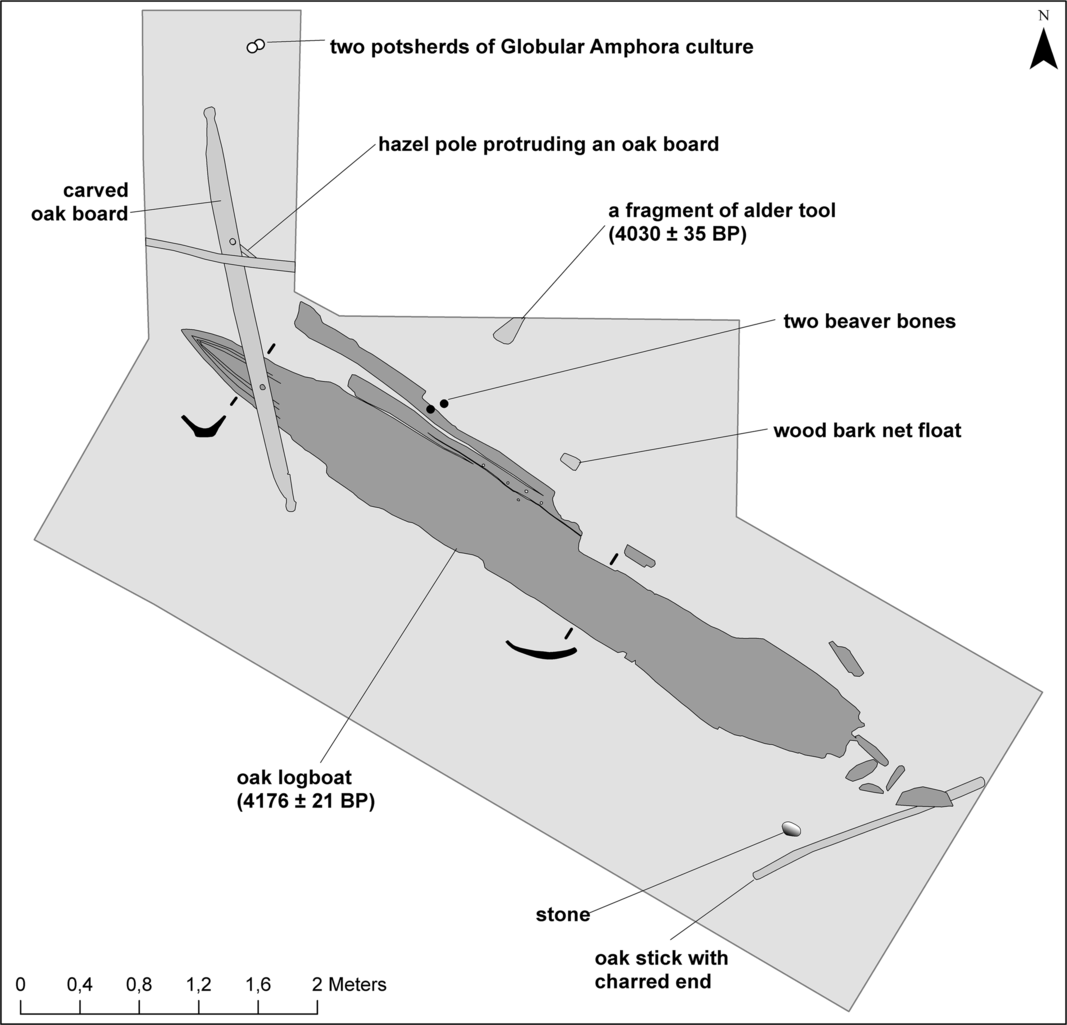

Table 1 List of early logboats in Lithuania. *14C dates have been obtained and wood taxa have been identified microscopically for this study.

Recently Discovered Logboats

In this paper we present 8 recently discovered logboats. Five of them, Asveja 3–4 and 6–8 were found during an underwater survey in Lake Asveja in 2018 and 2019. They were dated to ca. 1150–1800 cal AD (Table 1). A logboat with two bulkheads was discovered on a littoral shallow of the partly drained Nelinda Lake by local residents in 2012 year. It was made of a spruce trunk and sample Vs-2934 was dated to 150 ± 23 BP (1667–1950 cal AD) (Table 1). In 2018 a logboat lying in the bed of Žeimena River was found in Šakališkė village. This dugout boat was made of oak wood and sample Vs-2936 was dated to 2573 ± 27 BP (810–591 cal BC). It is the first and only logboat attested from the Bronze Age in Lithuania so far.

In 2015 the oldest dugout boat among all Lithuanian logboats was discovered during archaeological excavations of the wetland site of Šventoji 58. The site is situated in the northwestern part of Lithuania on the Baltic Sea coast (Figure 1). Here an extensive and complex field survey has been initiated with the aim to find new archaeological sites. Firstly, 127 boreholes were drilled and 8.34 km of GPR profiling was done in order to learn about paleoenvironment settings of the research area. After that, a systematic test-pitting of the area of 5 ha followed. More than 100 test pits 2 × 2 m in size were excavated every 20 m. The data collected allowed us to reconstruct the bed of paleoriver sculptured into gyttja during the Neolithic (Figure 2). This research revealed several new archaeological sites and it also helped prove that Šventoji 9, which was previously excavated and where a fish weir was found and dated to 1900–1800 cal BC (Rimantienė Reference Rimantienė2005), is a riverine site rather than lacustrine.

Figure 2 A research situation plan and a drone photograph of the research area at Šventoji 58 in 2015. The arrows mark the test pit where the Neolithic logboat was found. The Baltic Sea is situated behind the forest.

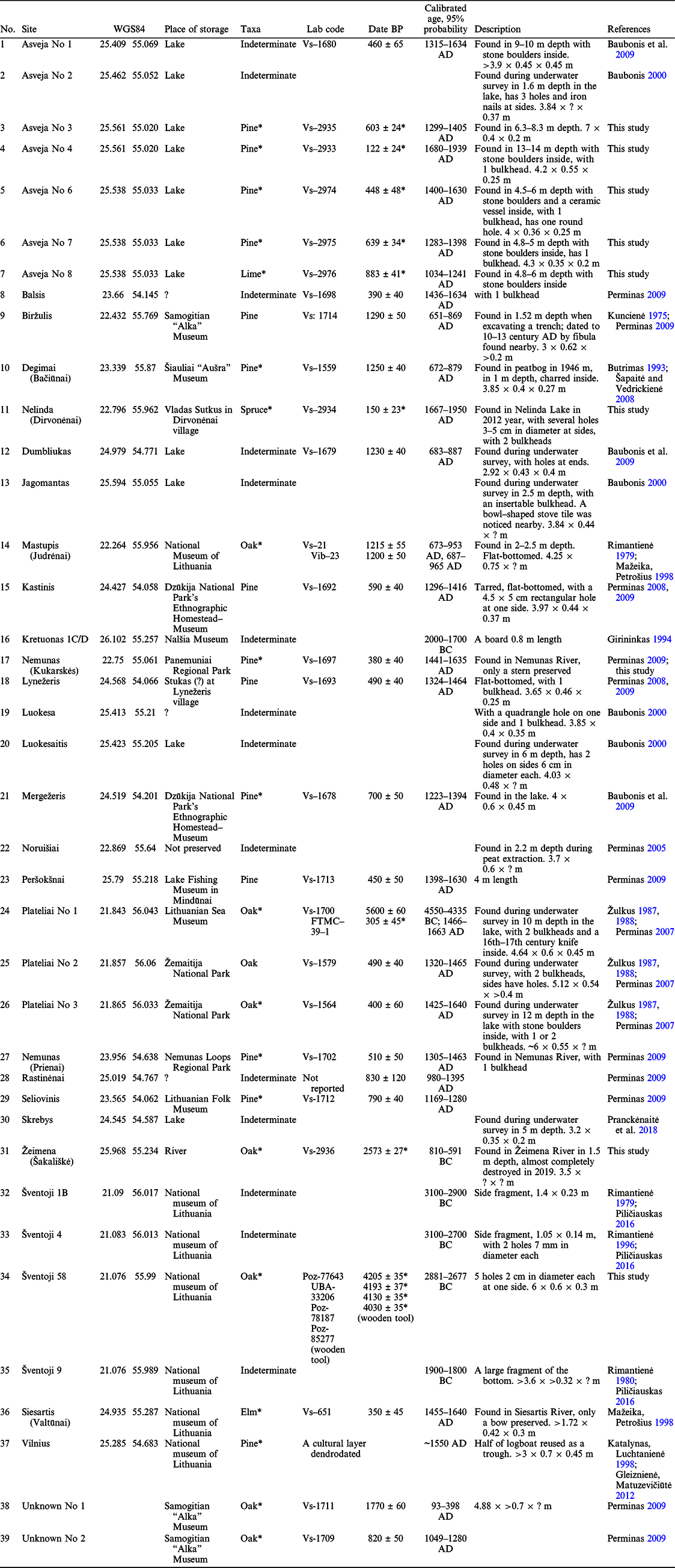

Remains of wooden fishing structures, including poles, planks and large bark fragments, were found within sediment filling the former riverbed at Šventoji 58. In test pit No 86, in the very bottom of the paleoriver, a logboat was uncovered (Figure 3). It was made of oak wood. The vessel was almost completely intact: only the stern and some boardside edges were missing or partially preserved (Figure 4). The size of the vessel was 6 × 0.6 × 0.3 m and its boards were only 1–2.5 cm thick, while the bottom was much thicker (4–8 cm). Its prow was pointed and slightly raised. This dugout boat had no ridges or bulkheads and its right sideboard has 5 round holes that are 2 cm in diameter each. The bottom was round excluding the flat-base bow which had a cavity 18 × 5 cm. Its current state could not be explained by any post-depositional processes, as the damage occurred in the thickest and best preserved part of the logboat. Therefore, we have deduced that the logboat had already been damaged during its use.

Figure 3 The Neolithic oak logboat found at Šventoji 58.

Figure 4 The Neolithic logboat and surrounding finds at Šventoji 58.

Few finds were found beside the logboat (Figure 4) including a net float made of tree bark and an oak board 279 × 14 × 2 cm in size and with 2 holes at the ends 3.5 cm in diameter each. A hazel pole was found inside of one of holes in a vertical position with its tip driven into the bottom of paleoriver. The second hole would also have had an inserted pole, although it did not survive. A carved board with hazel poles inserted into 2 holes represents a stationary construction with a changeable position of the board. It was possible to fix an oak board to the desired height by bandaging poles with any organic material in specific places. There are two possible functions of this construction. The board could have been used in the construction of a fishing trap consisting of a hoop net and 2 flank nets. It could have been fixed above the water surface with the aim of strengthening the two poles that kept the ends of the two flank nets attached to the hoop net. Similar fishing constructions were used along the Neman River until World War II (Piškinaitė-Kazlauskienė Reference Piškinaitė-Kazlauskienė1998). In order to retrieve a catch from the hoop net, a logboat had to be placed under the board, then the board had to be removed from the two poles, and after that a hoop net would have been placed inside the boat. Alternatively, the board may have been fixed below the river’s water table and the construction may have been used for keeping a logboat below water surface during winter time. The tradition of keeping dugouts underwater during winter time is well known among the Indians of North America (Patton Reference Patton2014). If we assume the latter interpretation, it is possible that the wooden construction could have kept the logboat underwater during wintertime. It would then follow that the vessel was intentionally sunk and stored for the last time by its owner, who did not return for it. As a result, this might have helped contribute to the good preservation of the logboat in a near-complete state, which over time was covered with peat after its deliberate sinking.

Logboat Chronology

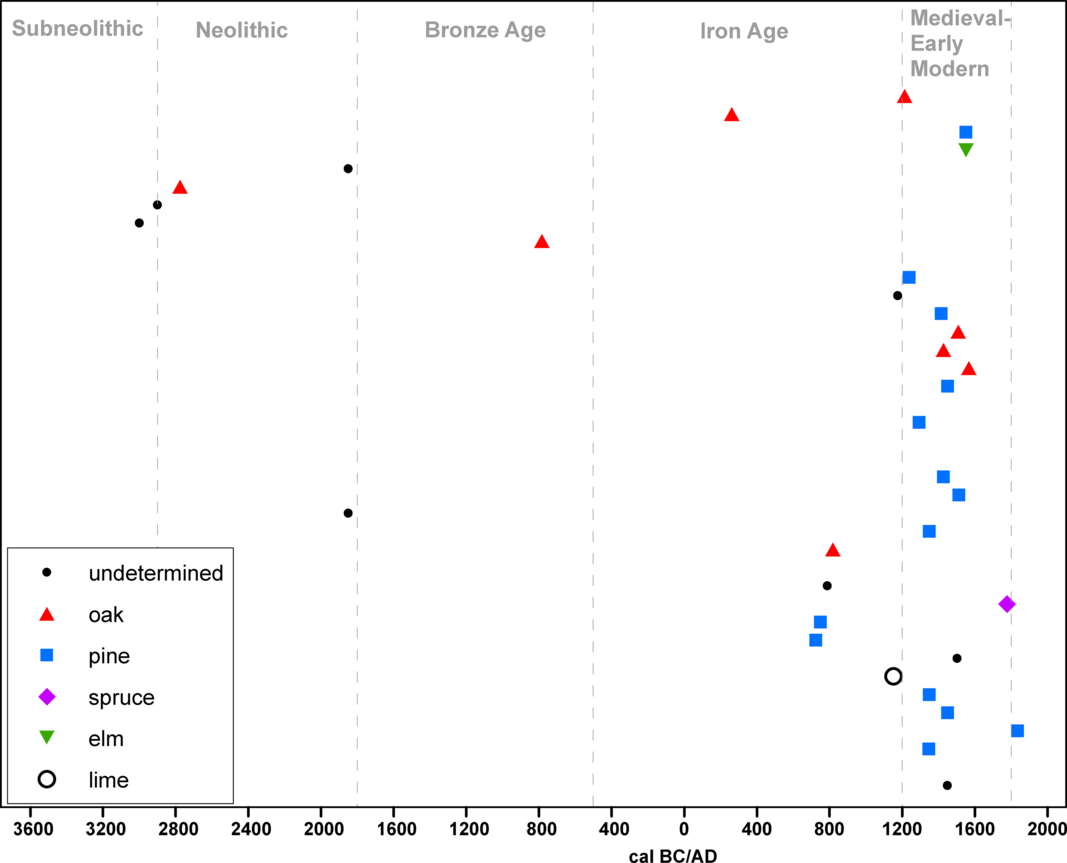

In Lithuania 35 ancient logboats or their fragments were 14C dated or came from 14C-dated contexts. From these 9 were dated for this study (Table 1). Nineteen vessels were dated to the medieval and early modern periods (1200–1800 cal AD), 5 to the Iron Age (500 cal BC–1200 cal AD), 1 to the Bronze Age (1800–500 cal BC), 3 to the Neolithic (2900–1800 cal BC), and 2 to the very end of the Subneolithic (4500–2900 cal BC) (Figure 5). None of the Lithuanian logboats discovered until now, however, appear to date to the aceramic Mesolithic. For several logboats more than one 14C date were acquired and these cases will be discussed below in more detail.

Figure 5 Wood taxa of early logboats from Lithuania plotted on a timeline.

The Šventoji 58 logboat was dated 3 times at 2 different labs. For all dates the same spot of logboat edge was sampled. The 3 dates that were obtained (Poz-77643: 4205 ± 35 BP; UBA-33206: 4193 ± 37 BP; Poz-78187: 4130 ± 35 BP) do not differ statistically significantly and can be combined into a single date 4176 ± 21 BP (2895–2640 cal BC) (Table 1). However, all 3 dated samples did not contain the youngest tree rings and therefore likely date the vessel to a period preceding the felling of the tree used in its construction and the boat use. Therefore, we suggest that a slightly later 14C date of the wooden alder (Alnus sp.) tool (paddle?) found right beside the logboat at the same depth would represent a more precise age of the logboat use—Poz-85277: 4030 ± 35 BP (2832–2471 cal BC). Two potsherds were discovered 2 m from the logboat and at the same depth. Both are from the vessel’s wall and lack any ornamentation. Judging by coarse mineral temper and smooth surfaces, the potsherds should be classified as Globular Amphora ware. Globular Amphora culture (hereinafter GAC) materials at Šventoji 4 were dated to ca. 2700 cal BC via the age-depth model (Piličiauskas Reference Piličiauskas2016) and this date fits well the dates of both the Šventoji 58 logboat (2895–2640 cal BC) and the alder tool (2832–2471 cal BC). This suggests that the Šventoji 58 logboat was made by GAC people ca. 2700 cal BC.

Another dugout boat that has been dated twice is logboat No 1 from Plateliai Lake. It is one of the three logboats found during an underwater survey in-between Pilies Island and the western coast of Plateliai Lake (Žulkus Reference Žulkus1988). All 3 logboats were of similar forms with 2 bulkheads each. Vessels No 2 and 3 were 14C dated to the 15–17th and the 14–15th centuries cal AD respectively (Table 1). However, logboat No 1 dated much older than the other two vessels: Vs-1700: 5600 ± 60 BP (4550–4335 cal BC). An iron knife dating to the 16th–17th century AD was found inside logboat No 1, which led previous researchers to question the date of Vs-1700 as implausible (Perminas Reference Perminas2007). To resolve this inconsistency, we proceeded to repeat the dating logboat No 1 from Plateliai Lake and received a date FTMC-39-1: 305 ± 45 BP (1466–1663 cal AD). The new date confirmed that the previous date for sample Vs-1700 was incorrect by more than 5000 years. We suggest that wood samples were confused during the first attempt of dating the vessel.

Stone Age logboats around the Baltic Sea

The Šventoji 58 logboat is the first nearly complete Stone Age vessel to have ever been found in the East Baltic region. All other logboats are either not dated via 14C dating, date to much later periods, or are only partly preserved. Much smaller fragments of Subneolithic and Neolithic logboats, however, are not as scarce in Latvia and Lithuania. They have been attested at the Subneolithic site Sārnate, which is situated in Western Latvia, 125 km north from Šventoji, as well as from the other Šventoji sites. In Sārnate only the pointed prow and a 2.3 m long section of one side of the logboat was preserved; it was made of an aspen tree trunk (Vankina Reference Vankina1970; Berzinš Reference Berzinš2000). Boards of various sizes, which may originate from the sides and bottoms of logboats were found at the other Šventoji sites, such as Šventoji 1B, 4, 9 (Rimantienė Reference Rimantienė2005). Some of them even have a row of holes similar to the Šventoji 58 logboat. However, forms, sizes, and the wood taxa that they were made of remain unknown.

If we consider the wider circum-Baltic area, Neolithic logboats are widely attested. Two Mesolithic and 1 Neolithic dugouts were found at Stralsund-Mischwasserpeicher in Northern Germany. They were made of broadleaf trees, such as lime and maple; therefore, their preservation was much poorer than that of the Šventoji 58 vessel. Two of them were 9 and 8 m long and 0.6–0.7 m wide, both dating to ca. 4700 cal BC or the Late Mesolithic. A third was 12 m in length and 0.6 m wide and was dated to ca. 3800 cal BC or the beginning of the Neolithic (Klooss and Lübke Reference Klooss and Lübke2006; Klooß Reference Klooß2014). More than 21 logboats are known at Late Mesolithic sites in Denmark (Christensen Reference Christensen, Pedersen, Fischer and Aaby1997). Logboats of the Ertebølle culture were usually made of lime wood, had a pointed bow, and some were up to 10 m long and had remains of fireplaces inside (Andersen Reference Andersen1986).

Only two Neolithic logboats are known from Poland. One of them was made from alder tree and is dated to 3694–3527 cal BC and was found in the Funnel Beaker culture site at Szlachcin near Poznań. Another example, owned by Regional Muzeum in Bydgoszcz, was dated to 2859–2469 cal BC (Lanting Reference Lanting2000; Ossowski Reference Ossowski2000). For the later one, however, no information on the cultural attribution and wood taxa was published. In Russia, Finland and Sweden no logboats 14C-dated to the Stone Age have been found so far. However, their use has been attested by rock carvings and 14C dates of wooden paddles (Okorokov Reference Okorokov1995; Lanting Reference Lanting2000; Kashina Reference Kashina2017; Kashina and Chairkina Reference Kashina and Chairkina2017).

Wood Taxa Used for Making Ancient Logboats

For this study we identified wood taxa for 20 logboats. Together with previous identifications, wood taxa are known for more than half (24/39) of all Lithuanian ancient logboats (Table 1). If these taxa used to construct these vessels are plotted along a timeline (Figure 5), some trends in the choice of the wood for logboat building are evident. Very few logboats were made of spruce (Picea sp.) and elm (Ulmus sp.). It is rather strange that among the Lithuanian ancient logboats very few are made of lime (Tilia sp.) or aspen (Populus sp.), which have been used in neighbouring regions and which are preferred taxa in modern logboat building. Pine (Pinus sp.) was without a doubt the most commonly used tree for dugout boats (14/24) in Lithuania. However, most of pine vessels date to the medieval and early modern periods. There are fewer older dugouts, but it seems that oak (Quercus sp.) wood instead of pine wood was widely used during the Neolithic, Bronze Age, and Iron Age. During the Middle Ages, more advanced boats made of wood planks were produced in addition to logboats. It may be speculated that the functions of logboats were reduced and the number of people using them decreased. Perhaps there was no longer a need to invest as much effort into the production of a durable oak logboat. Alternatively, the choice for pine could be determined by the increased value of oak timber in the Middle Ages. Such tendencies were observed in the Southern Baltic from 15th and 16th centuries when oak became mostly an export good and pine became the predominant wood taxon used for architecture and other purposes (Wazny Reference Wazny and Fraiture2011).

The use of oak wood makes the Šventoji 58 logboat different from numerous Stone Age logboats found in the Baltic area. Other taxa were preferred instead of oak by hunters-gatherers around the Baltic. It is interesting to note that other tools made of oak wood have been discovered in very close proximity to the Šventoji 58 logboat (Figure 4), and they demonstrate a wide use of oak in coastal Neolithic. Perhaps an increase in the usage of oak wood is related to the use of a new technology like ground square flint axes, which were frequently used by GAC people in Central Europe and Lithuania (Brazaitis, Piličiauskas Reference Brazaitis and Piličiauskas2005). GAC does not have roots in the local Subneolithic culture, but it was brought by migrants from Central Europe in 3200–2700 cal BC (Piličiauskas Reference Piličiauskas2016). Genetically, GAC people from Ukraine and Poland share ancestry with Anatolian farmers and differ greatly from the Eastern and Western hunters-gatherers (Tassi et al. Reference Tassi2017; Mathieson et al. Reference Mathieson, Alpaslan-Roodenberg and Posth2018). Šventoji 58 logboat evidences that ca. 2700 cal BC, in addition to new pottery types (GAC, Rzucewo, and Corded wares) and a new set of stone tools (e.g. square flint axes, battle axes), a new tradition of woodworking was introduced into the Eastern Baltic by Neolithic people. However, new excavations at wetland sites with GAC materials including wooden tools are needed to confidently confirm this hypothesis.

It seems that in other regions oak wood became more widely used in the production of logboats from the beginning of the Neolithic. In Slovenia, an oak logboat from Hotiza has been dated to ca. 6300–6100 cal BC (Erič Reference Erič2012). In Italy, the Lago di Bracciano oak vessel has been dated to ca. 5600–5400 cal BC (Fugazzola Delpino and Mineo Reference Fugazzola Delpino and Mineo1995). In Denmark, the first oak logboats appeared during the Funnel Beaker culture period starting from ca. 4000 cal BC (Lanting Reference Lanting2000). The Funnel Beaker culture people introduced a new kit of polished stone tools into the Western Baltic similar to what the GAC people did 1000 years later in the Eastern Baltic.

A Few Notes on Logboat Typology

Lithuanian logboats have already been discussed in several publications (Kuncienė Reference Kuncienė1975; Butrimas Reference Butrimas1993; Perminas Reference Perminas and Kazakevičius2005, Reference Perminas2007). In one study, a typology of prehistoric logboats was suggested (Perminas Reference Perminas and Kazakevičius2005, fig. 3). According to Perminas (Reference Perminas and Kazakevičius2005), Stone Age logboats have a round bow. However, this seems unfounded because when re-evaluating the evidence, it has been shown that all Mesolithic and Neolithic dugouts around the Baltic Sea have pointed bows rather than round bows (Figure 4; Christensen Reference Christensen, Pedersen, Fischer and Aaby1997; Berzinš Reference Berzinš2000). According to Perminas’ typology, bulkheads are a specific feature of Iron Age logboats. However, according to the data we collected (see Table 1), none of Lithuanian logboats dated to the Iron Age (500 cal BC–1200 cal AD) had any bulkheads or ridges. In fact, bulkheads are present on many medieval or even later logboats, including Asveja 4, Balsis, Dirvonėnai, Plateliai 1-3, and Lynežeris. The logboat typology that was suggested by Perminas includes many morphological traits that lack any clear chronological significance like the thickness of the bottom of the boat and logboat’s length. Using this typology for dating is problematic, as is well illustrated by an example of Degimai-Bačiūnai logboat. It was dated via the Perminas (Reference Perminas and Kazakevičius2005) typology to the Neolithic and then was re-dated a few years later via 14C dating to the 8th century cal AD (Šapaitė and Vedrickienė Reference Šapaitė and Vedrickienė2008). We suppose that the current number of ancient logboats in the East Baltic is too low to construct a reliable logboat typology at this stage. Furthermore, even with the considerably increased dataset of vessels it might appear that there was no linear evolution of logboats and that different logboat building traditions coexisted during particular periods, as it has been already noted for the other parts of Europe (e.g. Ossowski Reference Ossowski1999; Lanting Reference Lanting2000).

Conclusions

Of more than 70 logboats known in Lithuania, only about half were made before 1800 AD. Nineteen vessels were dated to the medieval and early modern periods (1200–1800 cal AD), five to the Iron Age (500 cal BC–1200 cal AD), one to the Bronze Age (1800–500 cal BC), three to the Neolithic (2900–1800 cal BC), and two to the Subneolithic (4500–2900 cal BC). At present, the logboat found at Šventoji 58 is the oldest 14C-dated (2895–2640 cal BC) logboat found East of the Baltic Sea. Medieval and early modern logboats were made out of pine and oak wood. From the very scarce dataset available, it seems that oak wood was introduced into logboat building by Neolithic people who also brought new technologies in stone tool production. The current number of prehistoric logboats in the East Baltic is too low to construct a reliable logboat typology today. Therefore, a direct 14C dating is still needed for every logboat for which the number has grown mainly due archaeological underwater survey and the increase in recreational diving.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all museums and private owners who kindly supplied us with samples. A local diver, Aldas Matiukas, provided us with valuable information about logboats that were situated in Lithuanian riverbeds and lakes, and we are truly grateful for his help. We are also thankful to Associate Editor Charlotte Pearson and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on a previous version of the manuscript as well as to Annette M. Hansen for language editing.