In 2010, President Obama signed into law the Plain Writing Act, which requires federal agencies to write in clear language. The law offers hope to citizens everywhere who squint in agony to decode the cumbersome terminology, baffling abbreviations, and tortuous circumlocutions that bureaucrats reel off with thoughtless abandon. When citizens need facts about health care, housing, and immigration, they should not have to suffer through clumsy jargon and mind-bending syntax. The government should make sense.

So, too, should the articles about government, particularly in the premier journals of political science. Yet, scholarly writing is infamously verbose, vague, and tedious to read. Surveys of academic journals show that most scholars across all fields flout the basic principles of good writing (Sword Reference Sword2012a). More generally, specialists from every profession contrive idiosyncratic terms and opaque phrases that drag down their sentences. Can political science, like the government, do better?

Take this sentence from a recent article:

Within these cases, increasing publicity is likely to be consequential to the de-legitimation of non-state violence when three important conditions obtain.

The same ideas could be expressed more concisely and concretely:

Publicity tends to undermine vigilantes under three conditions.

We collected this example and over a thousand more from an issue of the American Political Science Review (APSR). We looked for the most common faults that encumber writing in political science. In this article, we describe these problems and the principles of style for improving them.

Many sentences in the APSR suffer from heavy noun phrases suspended by weak verbs such as be, have, do, and make. The noun phrases acquire their bulk when the writer clusters multiple nouns and adjectives in forms such as noun noun noun and adjective adjective noun noun. The last noun in the cluster is the head of the noun phrase, and the words before it are modifiers that modify the head. Here are some examples with the head of each phrase underlined:

-

• precinct-level incumbent party electoral support

-

• socially generated political information

-

• canonical probabilistic record linkage model

-

• today’s cutting-edge quantitative social science research

-

• more nationally focused and ideologically conservative coverage

-

• knowledge-based service sector economy

-

• borderline statistically significant five-percentage-point increase

-

• historical monthly mean air temperature and precipitation data

-

• large-scale, racially-disparate voter demobilization

-

• political science’s deliberative democracy and organizational behavior’s procedural justice literatures

We will see that these swollen phrases defy the principles of good writing found in every style manual (Fowler Reference Fowler1926; Garner Reference Garner2003; Gowers Reference Gowers1954; Strunk and White Reference Strunk and White1959; Sword Reference Sword2012a; Williams Reference Williams1990; Zinsser Reference Zinsser2006). Specifically, we examine five contributors to heavy noun phrases and other turgid prose: piled modifiers that obstruct the head noun at the end; needless words like redundant heads and modifiers; nebulous nouns that add little meaning and require too many modifiers; missing prepositions that could better specify relations; and buried verbs that entomb actions in static nouns.

We also explain why these constructions feel so ungainly, invoking research in cognitive science about how people comprehend written language (Pinker Reference Pinker2014). Namely, a sentence feels burdensome when our mind’s parser struggles to resolve lengthy phrases, deep nesting, and ambiguous branching that tax its working memory.

Good writing, then, is not only a matter of aesthetics but also a matter of cognitive costs and benefits. The cost is the time and effort a reader spends to understand a sentence, and the benefit is the new understanding it conveys. Fluent writing is more profitable for readers, conveying more meaning at a lower cost.

The main reason to write clearly is obvious: the point of writing is to convey ideas to readers so obscure writing wastes our efforts and diminishes our research. Do readers understand our ideas as we intended? Do they stop on the first page and decide it is not worth decoding? If readers misunderstand or give up, the research might as well not exist. And even if readers eventually decipher the message, it is still inconsiderate to waste their time and effort. This reflects badly on the writer, which brings up a third reason: good writing earns the reader’s trust. Investigators make many decisions behind the scenes that affect the quality of their work. When their writing is accurate, logical, and thoughtful, readers can be reassured that the rest of the research was conducted with the same care.

The main reason to write clearly is obvious: the point of writing is to convey ideas to readers so obscure writing wastes our efforts and diminishes our research.

TURGID PROSE IN POLITICAL SCIENCE

To assess the state of prose in political science, we examined 18 articles from a recent issue of the APSR (volume 113, issue 2). We analyzed the articles according to the principles endorsed by experts in English usage (Fowler Reference Fowler1926; Garner Reference Garner2003; Gowers Reference Gowers1954; Strunk and White Reference Strunk and White1959; Sword Reference Sword2012a; Williams Reference Williams1990; Zinsser Reference Zinsser2006), justified and refined with insights from the psychology of language (Pinker Reference Pinker2014). We also follow the methods of usage guides: we present a principle, provide examples that violate the principle, and revise the examples to show how they improve. To document common problems, we collected more than 1,000 errant phrases and revised each one. We examine subsets of these examples and present the full set with citations in the online appendix.

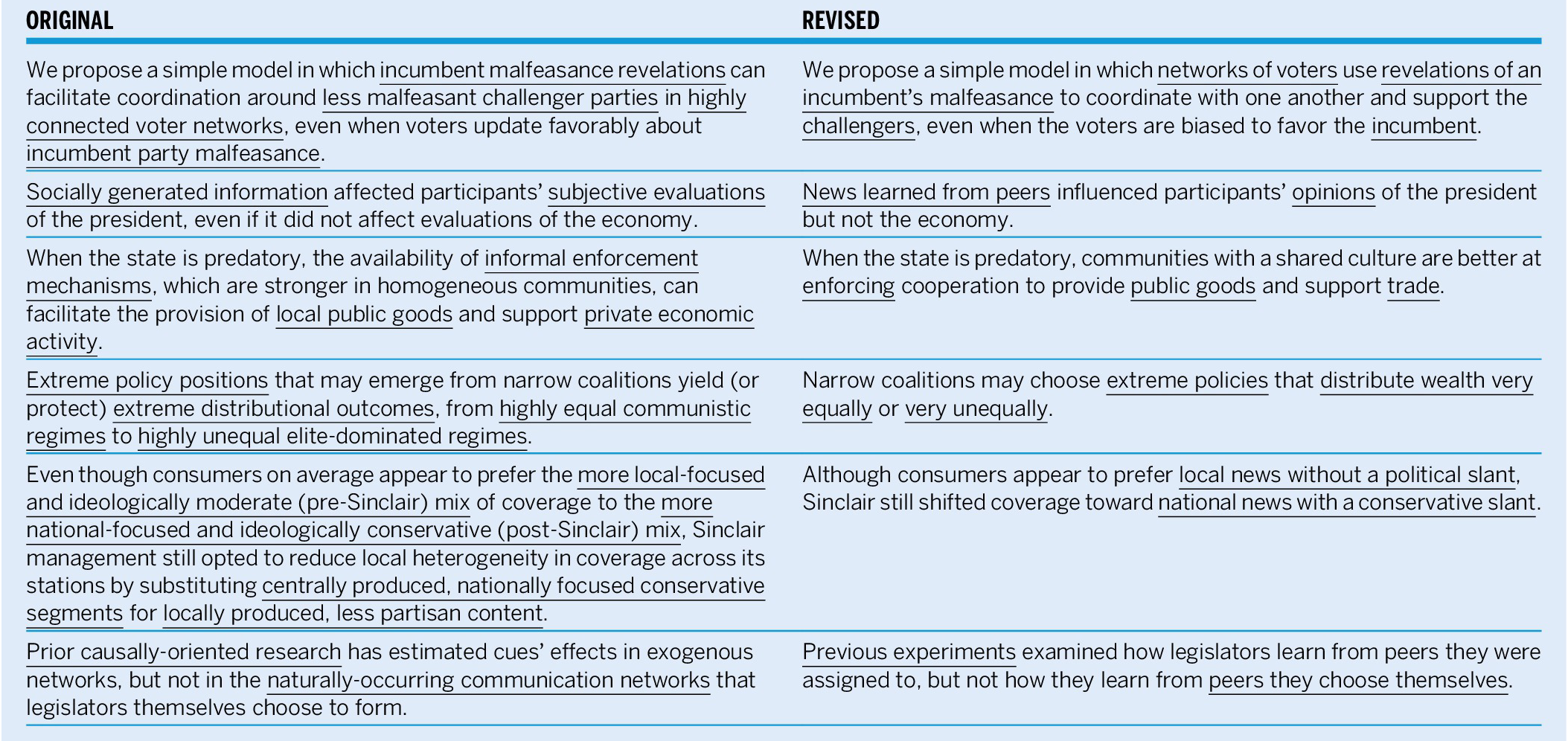

Table 1 presents sentences that illustrate common faults. As we mentioned, a persistent problem is the bloated noun phrase. Some sentences teeter under the load of not just one but three or four of these phrases. In every case, the sentence flows more gracefully when we revise the bulky phrases. Let’s look at the principles for doing so.

Table 1 Original and Revised Sentences from the APSR

Note: The underlined text indicates heavy noun phrases on the left and the corresponding revisions on the right.

Piled Modifiers

Noun phrases become unwieldy when writers pile modifiers before the head. Consider this example:

Contrary to abstract national economic aggregates (e.g., GDP or unemployment rates), which they receive in the form of mass-mediated—and politically disputed—information, voters can gauge (local) economic conditions “au natural” from various direct and more subtle cues in their residential setting.

Figure 1 shows the first pile, abstract national economic aggregates. The head of the phrase is the noun aggregates (underlined) at the end, which has three modifiers piled before it. To unstack the pile, we substitute indicators as the head and move the modifiers into a prepositional phrase that follows the head. We omit the modifier abstract because it is obvious. After revising the remaining piles, we can state the point more directly:

Voters do not need to gauge the local economy from indicators of the national economy such as GDP or unemployment; they can just look around their neighborhood.

Figure 1 Piled Modifiers and an Unpiled Revision

Piled modifiers are easy to recognize and revise. Scan a sentence for nouns and count the modifiers before each one. Phrases with more than one modifier deserve a second look. Often, we can unpile the modifiers and lay them out in prepositional phrases or relative clauses (modifiers introduced by that or a wh- word).

Modifiers are not the same as adjectives. In modern linguistics, grammatical functions such as modifier, subject, object, and head are distinct from grammatical categories (parts of speech) such as noun, verb, and adjective. Nouns can be modified by other nouns, by verbs, or by entire phrases. For example, the phrase highly connected voter networks (table 1, first sentence) consists of the head noun networks preceded by three modifiers: the adverb highly, the adjective connected (derived from the verb connect), and the noun voter.

Writing experts advise authors to unpile modifiers. The reasons begin with the maxim to apply modifiers sparingly. Mark Twain (Reference Twain1880) famously remarked, “When you catch an adjective, kill it. No, I don’t mean utterly, but kill most of them—then the rest will be valuable.” In The Elements of Style, Strunk and White advise, “Write with nouns and verbs, not with adjectives and adverbs” (1959, 68). These authors conflated the grammatical category “adjective” with the grammatical function “modifier,” but the point is the same: effective writing emphasizes “nouns and verbs, not their assistants” (Strunk and White Reference Strunk and White1959, 68).

The problem only worsens when the modifiers pile up. Worst of all is the noun pile, in which the head noun is crushed by a mound of other nouns conscripted as modifiers. Here are some examples from the APSR:

-

• incumbent party vote share

-

• networks’ coordination and information diffusion mechanisms

-

• fixed-effects dynamic panel regression models

-

• postdemocratization income inequality dynamics

-

• target group’s detection technology

-

• individual-level housing price change variable

-

• PCC’s street-level drug business

-

• accountability and preference aggregation functions

-

• absolute value percentage-point shifts

Gowers (Reference Gowers1954, 103) calls this problem the “headline phrase” caused by the “excessive use of nouns as adjectives,” and he laments that “its abuse is corrupting English prose.” In Garner’s Modern American Usage, Garner calls this a “noun plague,” and he explains:

Readability typically plummets when three words that are ordinarily nouns follow in succession…as when writers refer to a participation program principal category or the retiree benefit explanation procedure. (2003, 557)

The guidelines for the Plain Writing Act advise writers to “avoid noun strings” (plainlanguage.gov). In On Writing Well, Zinsser (Reference Zinsser2006, 76) warns of the “disease that strings two or three nouns together….Nobody goes broke now; we have money problem areas. It no longer rains; we have precipitation activity or a thunderstorm probability situation. Please, let it rain.”

In The Sense of Style, Pinker (Reference Pinker2014) shows how the classic maxims of writing are consequences of the psychology of understanding language. The mind represents meanings in a web of ideas. The nodes are concepts that represent people, objects, places, and events; the links between the nodes represent their attributes and relations. To communicate a portion of this web to another person, the speaker or writer must linearize it into a string of words that can be produced one at a time. After receiving this string, the listener or reader must recover the corresponding portion of the speaker’s web of ideas. We perform this magic by using rules of syntax as a cipher to convert networks of concepts into strings of words and back again. When the syntax is convoluted, the mind becomes taxed by unresolved fragments of trees that burden working memory.

A writer who piles modifiers places several cognitive hurdles in the path of the reader (Pinker Reference Pinker2014). In the syntax of English, the head of the noun phrase precedes its complements and generally appears as the first or second word in the phrase. Piled modifiers tax working memory because the reader encounters a series of modifiers before finding out what they modify. Further, the piled modifiers create ambiguity because each modifier could apply to the head or to another modifier in between (Stageburg Reference Stageburg1968). For example, in canonical probabilistic record linkage model, what is probabilistic: the record, the linkage, or the model? Even when it eventually becomes clear, ambiguous syntax delays the reader’s parser as it evaluates multiple branchings that are consistent with the string of words.

The costs multiply when we add several piles to a sentence and then combine these convoluted sentences into inscrutable paragraphs. A reader can concentrate to resolve a heavy phrase every so often but one after another soon becomes illegible. Across sentences and paragraphs, readers need to keep track of the characters and events that connect the author’s arguments and narrative (Pinker Reference Pinker2014; Williams Reference Williams1990). They look for the nouns—particularly the head nouns—to find the main characters, including the ideas and facts of an argument. When the head nouns are crowded by piles of modifiers, readers can easily lose the thread.

The costs multiply when we add several piles to a sentence and then combine these convoluted sentences into inscrutable paragraphs.

Needless Words

Needless words swell noun phrases and sentences. Let’s look at some examples from the APSR presented in table A1 in the online appendix. We can revise them by following the prime directive from Strunk and White (Reference Strunk and White1959, 23): “Omit needless words.”

Many modifiers are implied by the head noun or previous material. In an article about merging data, the analyses must follow the merge so there is no need to specify post-merge analyses (18 times). Stating that the mayor is malfeasant generally implies that challengers are not so an author probably does not need to spell out less malfeasant challenger parties (11 times). In an article about experiments, there is no need to specify experimental participants, experimental treatments, experimental results, experimental research, and experimental design (47 times).

We can also economize by applying modifiers once or as needed. After an author clarifies that she means information diffusion (22 times), socially generated messages (8 times), or probabilistic record linkage (10 times), she can simplify to diffusion, messages, or linkage when it is clear that the modifiers still apply. Consider how we would tell a story about a truck. After we clarify that a man drives a four-wheel-drive pickup truck, we would not repeat that he drove the four-wheel-drive pickup truck, turned the four-wheel-drive pickup truck, parked the four-wheel-drive pickup truck, and so on. Once we state the type of truck, we can simply say truck, applying modifiers as needed rather than compulsively.

Similarly, we can sever any head that is redundant. Experimenter demand implies an effect, an instrumental variable implies an approach, and the local economy already has conditions. Short phrases also improve: we can rewrite inequality levels (54 times) as inequality, voting behavior (7 times) as voting, and survey instrument (5 times) as survey. Inequality is about levels, voting is a type of behavior, and a survey instrument is simply a survey.

Beyond the noun phrase, needless words circle around an idea that could be stated directly. For instance, the phrase an exacerbated reaction to a contemporaneous trigger simplifies to a momentary overreaction. The phrase could potentially be imposing negative externalities on the quality simplifies to could be reducing the quality.

Trimming needless words reduces the cognitive demands on the reader. Every additional word forces the reader’s mind to recall its meaning and to fit it into the sentence’s syntactic tree (Pinker Reference Pinker2014). Each time we repeat a bulky phrase, the costs accumulate. Readers, moreover, assume that each word adds a new element of meaning (Grice Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975). When words are redundant or superfluous, the reader stalls to look for a new actor or object or quality where none is to be found.

Nebulous Nouns

Noun phrases may be clouded by nebulous nouns. Table A2 in the online appendix presents examples. To clear them up, replace abstractions with more precise and imaginable words. Strunk and White (Reference Strunk and White1959, 21) advise, “Prefer the specific to the general, the definite to the vague, the concrete to the abstract.” Garner (Reference Garner2003, 9) calls the problem “abstractitis.”

Nebulous nouns expand noun phrases by requiring too many modifiers. The head of a noun phrase, whenever possible, should be a concept that we can visualize rather than a metaconcept, that is, a concept about concepts such as level, outcome, approach, model, process, framework, perspective, mechanism, activity, information, and context. Metaconcepts are too wispy to convey the images that ground ideas in experience. Authors reach for modifiers to compensate but as Strunk and White (Reference Strunk and White1959, 68) advise, “The adjective hasn’t been built that can pull a weak or inaccurate noun out of a tight place.”

For instance, the noun context could refer to anything, so it is a baffling choice when the author means neighborhood, as in local residential context. Once we replace the head with neighborhood, we can drop the modifiers. Similarly, information is so vague that the writer must add modifiers to narrow the meaning, as in incumbent performance information, that is, misspending, and socially generated information, to wit, talking. The heads of these phrases need transplants, not band-aids.

Many generic heads bubble-wrap the object that the author has in mind, obscuring its shape and material: activity for trade, resources for funds, sentiment for resentment, attitudes for opposition, and structure for law or threat. Instead, use the specific noun and put the referent in plain sight. Similarly, we can often replace abstract, polysyllabic modifiers with concrete, concise, and familiar words, such as replacing endogenous organizational with private, highly heterogeneous with very different, and egotropic pocketbook with personal finances.

Notice how nebulous nouns can transform any ordinary idea into academese: Take a concrete idea (such as an apple), refer to it with a broad category (unit), and then add modifiers to compensate (edible seed dispersal unit). With similar alchemy, we can transmute a forest into a perennial ecosystem context, a love letter into amorous attitude information, and petting a cat into feline affection provision.

Nebulous nouns also accumulate when we forgo a specific verb. When discussing people who engage in criminal behavior, we could choose the specific verb commit, as in people who commit a crime. Similarly, we could choose the specific verb comply—just two syllables—to replace adopt external behaviors that are compatible. And instead of writing that jail sentences have a negative causal effect on voting, in the popular jargon of causal inference, we could choose a specific verb that succinctly expresses causation and negative effects: jail sentences decrease, reduce, deter, or discourage voting.

Nebulous nouns burden the reader’s mind with too many possible meanings. Abstract concepts refer to wide categories with more members than narrower concepts, so the reader may struggle to imagine the scene or may be misled by unintended images. Cognitive psychologists distinguish concepts by their generality: subordinate, basic, and superordinate, such as starling, bird, and animal, respectively (Rosch et al. Reference Rosch, Mervis, Gray, Johnson and Boyes-Braem1976). Basic concepts are easier to visualize and remember than superordinate concepts. And people reason more logically with concrete concepts. For instance, the notorious fallacies in Bayesian reasoning (Tversky and Kahneman Reference Tversky and Kahneman1974) disappear when participants judge facts presented in natural frequencies (e.g., “In every 1,000 women, 10 have breast cancer”) rather than abstract probabilities (e.g., “The probability that a woman has breast cancer is 0.01”) (Gigerenzer and Hoffrage Reference Gigerenzer and Hoffrage1995).

Missing Prepositions

Another contributor to stuffy verbiage is the missing preposition (see table A3 in the online appendix). Instead of jamming nouns and adjectives together, authors can clarify how they are related with prepositions like of, for, on, by, with, before, and against.

Gowers advises, “nursery school provision is not at present regarded as a proper way of saying the provision of nursery schools” (1954, 104). In Writing Successfully in Science, O’Connor recommends, “Insert verbs or prepositions between groups of three (or at most four) nouns, or nouns plus adjectives” (Reference O’Connor1991, 104). Similarly, Walsh recommends, “these modifiers should be framed with a few extra words and moved to the back” (Reference Walsh2000, 97).

By using a preposition to move a modifier after the head, the reader learns what the phrase is about before adding modifications. Beginning with the head noun also clarifies ambiguous syntax. The phrase high- and low-inequality autocratic countries is slow to understand because the mind must evaluate alternative nestings. But autocracies with high and low inequality is clear from beginning to end. The preposition also pinpoints how the modifiers modify the head. In anti-refugee political engagement, the reader gropes for what is being engaged; in political engagement against refugees, the mystery is solved. Also note the overuse of -level, anti-, pre-, and other hyphenated compounds in place of a preposition. A firm-level field experiment obscures that the experiment is on firms.

Buried Verbs

A final maxim is “Let verbs be verbs”—do not mummify them into nouns with suffixes like -tion, -ication, -ment, -ing, and -ance (see table A4 in the online appendix). The verb in a sentence brings it to life in the theater of our imagination. As Sword explains, “Verbs power our sentences as surely as muscles propel our bodies” (Reference Sword2016, 5). Vigorous sentences stride with actions such as reveal, punish, estimate, govern, and impede, even when they describe abstract ideas. Sluggish sentences waste the precious slot for an energizing verb on generic relations like be, have, do, and make and then bury the action in static nouns: revelation, punishment, estimation, governance, and impediment.

A noun derived from a verb is called a nominalization. Nominalizations serve as shorthand for an event that was previously presented (Pinker Reference Pinker2014; Williams Reference Williams1990). But nominalizations become compulsive among academics and bureaucrats who discuss the same events so many times that they forget readers need to see them played out. Garner calls them “buried verbs” and advises, “Buried verbs ought to be the sworn enemy of every serious writer” (2003, 117). Sword (Reference Sword2012b) calls them “zombie nouns” because “they cannibalize active verbs.”

Nominalization turns verbs into more fodder for swelling noun phrases. The phrase incumbent malfeasance revelation, for example, stuffs the verb reveal inside a noun and jams its object, malfeasance, before the nominalization instead of after the verb. Similarly, the phrase prison-based criminal governance encases the action govern, which forces the cast of characters out of the natural order: leaders govern gangs from prison.

Freeing verbs clears the needless words that grow like weeds around a grave. Instead of writing there is an empirical contribution in this paper by providing new evidence, we can unearth the verb contribute and simplify to this paper contributes new evidence. Instead of institutions through which public legitimation can be accomplished, we can free the verb legitimize, restore its object, violence, and simplify to institutions that legitimize violence.

In general, when writers bury the verb in a noun, the reader must stop to exhume the action, find the subject and object, which are often missing, and then mentally rearrange these concepts to follow the natural order in English: subject, verb, object. We can easily spare readers the trouble by expressing actions with verbs so they can find the subject and object in the standard slots and mentally animate the scene right away.

When writers bury the verb in a noun, a reader must stop to exhume the action, find the subject and object, which are often missing, and then mentally rearrange these concepts to follow the natural order in English: subject, verb, object.

Baffling Abbreviations

Along with the five remedies for bulky phrases, another should be avoided: abbreviations. Abbreviations represent an unfair bargain: the writer saves a few keystrokes while the reader is forced to memorize an arbitrary sequence, pause repeatedly to recall the translation, and backtrack when recall fails. Examples from the present sample include EDEs (91 times), DMA (43 times), and SWIID (12 times). Instead, writers can shorten long phrases with an informative nickname (see plainlanguage.gov, “Minimize Abbreviations”). For example, we could use demand for experimenter demand effects, area for designated market area, and inequality database for the Standardized World Inequality Indicators Database.

CONCLUSION

A half century before the Plain Writing Act, the British government confronted the obscurity of officialese by inviting Sir Ernest Gowers to compose a writing manual for officials. The book, Plain Words, was issued to every department and became a classic of writing style. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, a Nobel Laureate in Literature, championed the cause: “I am in full sympathy with the doctrine laid down by Sir Ernest Gowers” (UK Parliament 1954).

Like the governments it studies, political science depends on writing to communicate accurately and efficiently. Analyzing the pages of the APSR, we found more than a thousand ungainly phrases suffering from piled modifiers, needless words, nebulous nouns, missing prepositions, and buried verbs. By revising many examples and explaining how and why we did so, we hope to have shown that these problems are easy to recognize and improve.

Writing is particularly important in the science of politics (Orwell Reference Orwell1946). With clear and precise sentences, political scientists can share their insights about vital issues such as democracy, war, and justice with their professional peers and concerned citizens alike.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for thoughtful comments from Alessandro Del Ponte, Andy Delton, Natalie DeScioli, Greg Huber, Hana Kim, Yanna Krupnikov, Laura Link, Nathan Link, Maxim Massenkoff, John Ryan, and Tim Ryan.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1049096521000810.