Recent trends in the pharmaceutical market such as fast approval of innovative products and the launch of expensive gene therapies have raised concerns about the sustainability of pharmaceutical spending (1). Some innovative medicines, which are often associated with high price tags, are approved under the so-called “Adaptive Pathways” by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) with yet limited and/or immature evidence (especially in case of orphan drugs) (2;3).

Both policy makers and pharmaceutical companies have been trying to find ways to balance access to innovation and sustainability of the healthcare budget and pharmaceutical sector. Under this circumstance, various forms of risk-sharing agreements have been implemented to address uncertainties around outcome and financial impact of some pharmaceutical products since late 1990s and growing fast since 2010 (Reference Espín, Rovira and García4–Reference Driscoll, Farnia, Kefalas and Maziarz6). Various taxonomies have been used in practice, including risk-sharing agreement, managed entry agreement (MEA), patient access schemes, performance-based agreement, payment by results, and so on. These arrangements have been grouped into two broad types—financially-oriented agreements (e.g. price-volume agreement, discounts in various forms) and outcomes-based agreements (or performance-based agreements) (Reference Grimm, Strong, Brennan and Waillo2). For example, Bluebird bio's beta thalassemia gene therapy Zynteglo (lentiglobin) has been authorized by the EMA through “Adaptive Pathways” in 2019. The manufacturer is in talks with national authorities and payers in Europe, proposing a plan considering an upfront payment plus annual payments over 5 years according to the performance of the product (7;8).

There has been a substantial body of literature focusing on the concepts of various forms of risk-sharing agreements (Reference Hutton, Trueman and Henshall9–Reference Towse and Garrison13). In 2013, the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Task Force introduced a definition of performance-based risk-sharing arrangement (PBRSA): “A plan by which the performance of a product is tracked in a defined patient population over a specified period of time and the amount or level of reimbursement is based on the health and cost outcomes achieved.” (Reference Garrison, Towse, Briggs and Pouvourville14) PBRSAs are characterized by including outcome and/or value to reimbursement/payment, and/or are linked to conditional terms (i.e. collection of evidence) or innovation (novel combination of factors) (Reference Kefalas, Ali, Jørgensen, Merryfield, Richardson and Meads15). However, little research has been done regarding when to select a certain arrangement and how to set up such arrangements to ensure success.

While PBRSAs have increasingly become an interesting area in practice, they are not a magic bullet for all products and in all settings. It is of fundamental importance to understand when such schemes could and should be considered. The ISPOR Task Force (Reference Garrison, Towse, Briggs and Pouvourville14) set out key guidelines for good practice of PBRSAs, including:

• It is critical to match the appropriate study and research design to the uncertainties being addressed.

• Good governance processes are essential.

• The ex post evaluation of a PBRSA should be a multi-dimensional exercise that assesses many aspects, including not only the impact on long-term cost-effectiveness and whether appropriate evidence was generated but also process indicators, such as whether and how the evidence was used in coverage or reimbursement decisions, whether budget and time were appropriate, and whether the governance arrangements worked well.

• PBRSAs should also be evaluated from a long-run societal perspective in terms of their impact on dynamic efficiency (eliciting the optimal amount of innovation).

To the best of our knowledge, there have been few recent reviews that attempt to summarize the international experience both in the US and Europe and elsewhere in a systematic way to inform other regions and countries. This study aims to review the literature with an eye toward the implications for the Chinese pharmaceutical marketplace.

Method

Information Source and Search Strategy

A systematic literature review was conducted to review publications regarding implementational experience, opinions, and debates of PBRSAs in the past 10 years (2009–2019). As PBRSAs have been implemented mainly in developed countries, including the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, France, and the Netherlands, publications reporting the experience of PBRSAs were restricted to these countries.

PubMed was searched using pre-defined search strategies (see Supplementary file 1: Search strategies). Variations of terminologies representing PBRSAs were used to search in title/abstract or as MESH terms. These terminologies included “risk sharing agreement,” “managed entry agreement,” “patient access scheme,” “outcome based agreement,” “performance based agreement,” “price volume agreement,” “innovative contracting,” “innovative agreement,” “pay for performance,” “risk sharing arrangement,” and the plural forms of these terms. Detailed search strategy can be found in the appendix. Only publications in English were searched and screened.

The following sources were also searched for grey literature of PBRSAs:

• UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), National Health Service (NHS)

• France: Ministry of Solidarity and Health, the French Health Authority (HAS)

• Italy: Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA)

• Spain: Ministry of Health (ISCIII), and seven regional health technology assessment bodies (Andalucía, Aragon, Basque Country, Canary Islands, Catalonia, Galicia, and Madrid)

• Canada: Ministry of Health of two large territories, including Ministry of Health and long-term care Ontario and Government of Quebec.

• US: Google

In the country-specific Websites, publications or reports in local languages were reviewed.

Study Selection

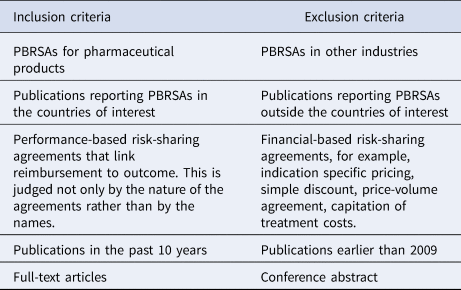

The identified publications were screened in two stages, namely title/abstract screening and full-text assessment. One reviewer (WXu) performed the search and screening. In title/abstract screening and full-text assessment phase, the following inclusion and exclusion criteria were adopted (Table 1). A second reviewer (JWu) was involved and a consensus was reached between the authors in case of any issues during the selection process.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria during selection

PBRSA, performance-based risk-sharing agreement.

Results

The search resulted in 499 records and 3 additional ones identified through other sources (i.e. reference from the identified publications). After removing duplicates, 464 records were screen by title/abstract. Four hundred publications were excluded based on title/abstract screening, leading to sixty-four publications being reviewed with full text. Using the pre-specified exclusion criteria, thirty-three publications were excluded. Thirty-one publications were included in the final review (Supplementary Table 1). The screening procedure is recorded using a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) (16).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram (16).

International Experience of PBRSAs

PBRSAs provide opportunities to all stakeholders (including patients, healthcare providers, payers, and pharmaceutical companies) upon the launch of an innovative product (Reference Gonçalves, Santos, Silva and Sousa17–Reference Klemp, Frønsdal and Facey19). Besides access benefits associated with PBRSAs, these agreements also provide opportunities to generate evidence in the real world and increase patient compliance (Reference Garrison, Carlson, Bajaj, Towse, Neumann and Sullivan20). The ISPOR Task Force emphasized the “public goods” nature of the real-world evidence generated via PBRSAs as countries can learn from each other's experience. The push for value-based pricing since early 2000s seems to be the theoretical basis of PBRSAs; economic crisis and as a consequence high incentives to contain costs is an important reason of seeking risk-sharing agreements by payers in case a simple discount is not achievable (Reference Piatkiewicz, Traulsen and Holm-Larsen21).

In practice, most risk-sharing agreements were indeed initiated to address payers' concerns of budget and value of a product (Reference Klemp, Frønsdal and Facey19). According to a payer survey (n = 66) conducted by Dunlop et al., 30 percent of the responders considered risk-sharing agreements in order to improve management of healthcare budgets by increasing certainty about future expenditure; 23 percent agreed that risk-sharing agreements can reduce risks for payers when long-term outcomes have not yet been demonstrated in the available data package; 27 percent of the responders agreed that risk-sharing agreements are helpful to find common ground between pharmaceutical companies and payers in terms of the value of medicines (Reference Dunlop, Staufer, Levy and Edwards22).

The types of risk-sharing agreements being implemented in practice reflect payers' needs. Payer's needs can be categorized in two major categories: (a) budgetary control and (b) improving the health of the covered population, depending on various factors such as nature of the payer (private vs. public), monopolistic position of the payer (single vs. multiple payer), and the extent of their financial responsibility, and so on. Morel et al. reported that among forty-two MEAs for twenty-six orphan drugs launched in seven European countries (Italy, the Netherlands, England and Wales, Sweden, Belgium, France, and Germany) between 2006 and 2012, 55 percent of them were PBRSAs and the other 45 percent were financial-based agreements (Reference Morel, Arickx, Befrits, Silverio, Meijden and Xoxi23). These PBRSAs included “outcomes guarantees” (i.e. payment for responders only), “money-back guarantees” (i.e. refund for non-responders or patients having discontinued), and “conditional treatment continuation” (i.e. payment for continued use of the medicine for those patients reaching a pre-defined intermediate treatment milestone).

The implementation of risk-sharing agreements has experienced various patterns over time in different countries (Reference Piatkiewicz, Traulsen and Holm-Larsen21;23;24). Italy has been one of the first countries entering into a wide range of MEAs and has insisted in this direction whenever a newly launched medicine presents some uncertainty around clinical value/effectiveness, budget impact, or potential inappropriate use (25–Reference Garattini, Curto and van de Vooren28). In the Catalonia region of Spain, it was observed that PBRSAs have been increasingly accepted by regional health authorities in the recent years (Reference Darbà and Ascanio29). England has started the implementation of PBRSAs since early 2000s (e.g. in multiple sclerosis and multiple myeloma) (Reference Palace, Duddy, Lawton, Bregenzer, Zhu and Boggild30). However, PBRSAs have been gradually shifted to patient access schemes in the format of confidential financial agreements (in this case, a discount) in England and Wales since 2012 (Reference van de Vooren, Curto, Freemantle and Garattini31). Similarly, the Dutch National Health Care Institute has also increasingly refrained from PBRSAs and switched to more straight-forward financial-based agreements since 2015 (Reference Morel, Arickx, Befrits, Silverio, Meijden and Xoxi23).

Compared to the European countries, no obvious trends of the use of risk-sharing agreements can be observed in the US and Canada probably due to the fragmented payer landscapes (Reference Barlas32).

Preconditions of a Successful Implementation of PBRSAs

The success of a PBRSA is proven to be very challenging and is ultimately determined by its ability to reduce the uncertainties regarding the cost-effectiveness of a product, its budget impact, the efficient use of a product in real life, or a combination of these (33;34). The following preconditions are summarized based on international experience of PBRSAs to enable a successful implementation of such schemes:

(1) Identify meaningful and feasible outcome measurements

Difficulty in defining meaningful and feasible performance measurements is considered as one of the key challenges of PBRSAs (Reference Gonçalves, Santos, Silva and Sousa17). In a hypothetical 1-year PBRSA for a product indicated in hypercholesterolemia, Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Sheer, Pasquale, Sudharshan, Axelsen and Subedi35) developed two models to simulate the outcome of PBRSAs using a range of inputs for medication effectiveness, medical cost offsets, and the treated population size. The two models are based on two types of clinical outcomes: surrogate end points (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol measurements and goals), as well as “hard” clinical outcomes (i.e. acute myocardial infarction and stroke). The two models result in different net costs per patient for payers depending on the threshold defined in the agreement in terms of under-performing and over-performing. The manufacturer reimbursement was higher in either PBRSAs compared to the scenario without an agreement due to a substantial increase of the size of treated population (in this case an increase from 500 to 1,000).

While the choice of outcome measurements can be a sensitive element in PBRSAs, what measurements should be used and whose perspective should be taken (payers, healthcare providers, and/or patients) in PBRSAs are often unanswered questions. In principle, it is a question of “value perceived by whom.” To our knowledge, there are only a few studies in this area. Neilson et al. published two studies (36;37) to identify meaningful outcome measurements in cardiovascular disease and diabetes using Delphi panels of payers and patients. In both studies, patients reported substantially different meaningful outcome (e.g. reducing of chest pain, quality of life, etc.). How to collect patient-reported outcomes data to help measure the value of a medication is yet unclear.

Even if all stakeholders reach consensus on the meaningful outcome measurements, it is crucial to ensure that relevant outcomes are feasible to collect in real practice. A Dutch hematological malignancies registry reported three issues related to measuring outcome in PBRSAs, namely confounding by indication, missing data, and insufficient comparable patient numbers (Reference Blommestein, Franken and Uyl-de Groot38). Also in the Netherlands, a PBRSA was arranged for oxaliplatin for the treatment of stage III colon cancer. Collecting additional data through a patient registry was required. However, it was found that patient heterogeneity made it problematic to estimate incremental cost-effectiveness of the treatment using the collected data (Reference Mohseninejad, van Gils, Uyl-de Groot, Buskens and Feenstra39).

(2) Establish an effective and efficient data collection infrastructure

Various types of data sources have been used to collect data for PBRSAs. According to a systematic literature review of PBRSAs in the US, electronic medical records have been used as data source for twelve (46 percent) of the identified agreements, followed by claims data (n = 11, 42 percent) (Reference Yu, Chin, Oh and Farias40).

The Italian AIFA Monitoring Registries System, organized in an established centralized data collection infrastructure, lowers the marginal cost of setting up each new PBRSA, as well as the barriers for the implementation of PBRSAs (Reference Morel, Arickx, Befrits, Silverio, Meijden and Xoxi23). As a potential consequence, PBRSAs accounted for 29.8 percent of the total amount of €41.1 million pharmaceutical budget under all types of risk-sharing agreements in Italy in 2012 (Reference Navarria, Drago, Gozzo, Longo, Mansueto and Pignataro26). Up to 2018, there are 130 innovative drugs monitored on the AIFA registries (Reference Capozzi, De Divitiis, Ottaiano, Teresa, Capuozzo and Maiolino41).

In most countries, lack of data collection infrastructure is a hurdle that must be overcome to implement a successful PBRSA (17;20).

(3) Control costs associated with the implementation of PBRSAs

The implementation of PBRSAs can be costly (17;20). There are very few studies evaluating the implementational costs associated with PBRSAs. Garattini et al. (Reference Garattini, Curto and van de Vooren28) criticized that the Italian AIFA's estimation of time required by a hospital consultant (30 sec) and a pharmacists (10 sec) to complete one outcome form to be unrealistically low. The same author criticized the high administrative burden of PBRSAs that is often borne by healthcare providers (Reference Garattini and Curto42). A rough estimation of the implementational costs of PBRSAs can be somewhat reflected by the managerial fees that companies pay the entities that manage the patient registries, which is a requirement of AIFA. The fees varied between €30,000 and €60,000 in the first year including system setup, which was then more than halved in the subsequent years to maintain the system, depending on the complexity and potential workloads to collect clinical outcomes (Reference Garattini, Curto and van de Vooren28).

To be prepared for the launch of CAR T-cell therapy, NICE estimated a total administrative cost of £1,117,024 (equal to €1,308,880) for the CAR T with a PBRSA over 10 years (assuming 50 new patients each year) (Reference Kefalas, Ali, Jørgensen, Merryfield, Richardson and Meads15). Monitoring cost was a major component of the total costs, which were estimated to be £572,904 in year 1 and £401,813 in years 2 through 10.

The significant administrative burden needs to be carefully estimated and considered by both payers and companies before making decisions to proceed with PBRSAs.

(4) Develop a governance and administrative infrastructure to allow delisting and rebate/refund

Withdrawing a reimbursement decision when evidence no longer supports coverage is proven to be challenging, or even impossible due to a lack of exit mechanism based on economic evidence in most countries (34;43).

Furthermore, the current invoicing approach does not support complicated PBRSAs, with which pharmaceutical companies might need to pay back to payers or hospitals, or the other way around across consecutive fiscal years. Refund notification and arrangement have been for a long time an issue during the implementation of PBRSAs. In Canada, there are anecdotes that provincial government delayed invoicing associated with PBRSAs to pharmaceutical companies up to 12 months due to lack of such administrative infrastructure. In Italy, Garattini et al. (Reference Garattini and Casadei44) reported more than half of the refund (around €234 million out of a total turn-over of €422 million for cancer drugs) was not executed in 2009, partly due to the lack of a national refund procedure at that time.

(5) Clarify personal data protection issues

The implementation of PBRSAs needs access to patient-level treatment outcome data in many cases. Personal data protection is a challenge in many countries. What data can and can't be shared and analyzed? What data can be reported to support a payment decision? How to strictly restrict the use of patient data for justified purposes? Answers to all of these need clear and well-defined legal terms and administrative infrastructure of data processing (Reference Gonçalves, Santos, Silva and Sousa17).

Discussion

In countries where access pathways and HTA are still in the emerging phase—e.g. China (where HTA has been in place since 2017 to support price and reimbursement decisions), it is not too early to explore various forms of risk-sharing agreements at this moment to be prepared for the future launches of innovative and expensive products, especially curative therapies (e.g. gene therapies). The choice of risk-sharing agreements (financially-oriented or outcome-based) will be a case-by-case discussion depending on the needs of the stakeholders. Compared to the complex nature of PBRSAs, financial-oriented risk-sharing agreements are more straight-forward and are naturally the starting point for the Chinese payer. However, financial-oriented risk-sharing agreements do not address uncertainties around clinical outcomes, especially for drugs with conditional approval (e.g. orphan drugs). Therefore, we recommend that both payers and companies to pilot PBRSAs with the understanding of the complex nature of such schemes and be prepared for the launches of more products in marginal indications (Reference Fojo, Mailankody and Lo45).

The implementational challenges that are observed and summarized in this study are unavoidable in China. At the same time, a few specific characteristics of the Chinese healthcare system might either raise extra challenges or pave the way to future PBRSAs.

Firstly, outcome measurement can be extraordinarily challenging in China. Although both hospital-level medical electronic records and city-level claims data exist, data are available only in a fragmented manner, and there is little incentive from both healthcare providers and payers to link data across treatment episodes. Therefore, treatment journey of a specific patient cannot reliably be followed over a prolonged period. However, diseases that are most likely treated in only a few specialized treatment centers (e.g. severe ultra-orphan diseases) can to a large extent avoid this issue. In 2018, a patient registry system for orphan diseases was initiated by the medical community on the national level (i.e. Chinese national orphan disease registration system). This system might serve as a data platform for the National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA) to pilot PBRSAs in the orphan disease area by collecting required data (including patient characteristics, comorbidity, disease history, treatment history, detailed diagnosis, treatment, concomitant treatment, and outcome) in the future.

Secondly, quality of data is currently not high enough to support PBRSAs in China. For example, diagnosis is not well recorded with much missing data and random errors in the current hospital information system in China. For PBRSAs, diagnosis needs to be reasonably complete, accurate and analyzable, meaning that not only the first diagnosis by also comorbidities need to be well documented and reported. Very recently, the Chinese NHSA has announced the official start of piloting the diagnosis-related groups (DRG) system in China (46). Once DRG is implemented, hospitals are required to record correct diagnosis and comorbidities as these are directly linked to the DRG tariff. Although ICD creep has been widely reported in the implementation of DRG (Reference Hsia, Ahern, Ritchie, Moscoe and Krushat47), the DRG system motivates hospitals to record more detailed diagnostic information.

Finally, all stakeholders need to be strongly incentivized and engaged to make a PBRSA successful. PBRSAs should minimize the time needed from healthcare providers. In China, NHSA and the National Health Commission (NHC, representing the healthcare providers) are two independent departments. NHSA does not have enforcing power over NHC for the reporting of clinical outcomes in the case of PBRSAs. Thus, special attention needs to be paid when designing a PBRSA to ensure healthcare providers' engagement.

The study has certain limitations. Firstly, this literature review has a focus on Western countries. Literature in Asia-Pacific countries might provide more information and be applicable to the Chinese healthcare sector. Secondly, the grey literature search is to some extent less structured compared to a systematic search within databases. This is a common weakness of grey literature search. Thirdly, Due to the confidential nature of PBRSAs, there has been no publication reporting details of the conditions and post-evaluation of PBRSAs in any countries. Implementation of PBRSAs can be related to many factors, such as the design of the schemes, administrative structure of the healthcare systems, and so on. Without details of the contracts and proper evaluations, it is challenging to identify the key factors that enable or disable a PBRSA. Further studies are needed in this field.

Conclusion

PBRSAs should not be used as a standard reimbursement scheme or a leeway for manufacturers to avoid other straight-forward ways of price discount. It should be used only when absolutely needed, i.e. in case significant uncertainties around the (long-term) clinical value exist.

Effective implementation of PBRSAs in China would require careful thought and planning during the design and implementation phase to ensure success. Based on this review, the following preconditions and steps were identified to support a successful implementation of PBRSAs: (1) Identify meaningful and feasible outcome measurement; (2) Establish an effective and efficient data collection infrastructure; (3) Control-associated costs during implementations; (4) Develop a governance and administrative infrastructure to allow delisting and refund/rebate; (5) Clarify personal data protection issues.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462320000653

Acknowledgment

This research received no specific funding from any agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The authors would like to thank Ling-Hsiang Chuang, who reviewed this manuscript and provided comments.