Introduction

On a dry, sunny day in Senegal in 2018, I was conversing with the chief of a village located close to the fields of an agribusiness venture now called Les Fermes de la Teranga. When I asked the village chief if he had had a chance to meet the company’s social responsibility manager, he recalled the only visit that a delegation of corporate executives ever made to his village, long after farming had begun. “They made a lot of promises,” he said, “but they never came back. They made promises only to calm down the population.” A relative of the village chief who was present in the room added, in reference to the social responsibility manager, “She acted her role and left. Like a play.”Footnote 1

In the aftermath of the global food, oil, and financial crises of 2007–2008, the number of large-scale land acquisitions has soared worldwide. Touted as a fantastic business opportunity by its proponents, farmland investment has attracted many newcomers wishing to exploit this “untapped” agricultural potential (Li Reference Li2014:596) or to protect themselves from commodity price fluctuations. However, the high proportion of failed land deals globally and in Africa more particularly (Cotula Reference Cotula2013; Deininger Reference Deininger2011; GRAIN 2018; Nolte Reference Nolte2020) attests to the difficulties these investors face in implementing their projects.Footnote 2

In many cases, prospective investors are unable to even acquire land. When they do secure land de jure, land control de facto is not guaranteed. Several land deals in Africa have unraveled due, among other factors, to resistance from domestic state officials, local residents, and foreign and national civil society organizations (CSOs) (Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Campion and Gasparatos2017; Burnod et al. Reference Burnod, Gingembre and Ratsialonana2013; Gagné Reference Gagné and Bartley2019; Schlimmer Reference Schlimmer2019). Opposition to large-scale land acquisitions can generate significant economic loss, impose reputational damage, cause operational disruptions, and result in project terminations; in other words, it can preclude capital accumulation. Hence, to extract profits from the land, companies must not only acquire a concession in the first place, but they must also make legal rights effective to maintain de facto control over the land they own (Hall Reference Hall2011; Peluso & Lund Reference Peluso and Lund2011).Footnote 3

Processes of corporate land acquisition and retention remain, at their core, a question of power. They are the contingent outcome of contestations and negotiations among actors who compete to assert their claims or resist the claims of others. As suggested by the village chief’s comments above, to obtain and retain land control, both de jure and de facto, investors need to persuade governments and local populations of their anticipated benefits and limit dissenting voices when they emerge. This task is complicated by the fact that government responses to land projects can themselves be influenced by the reactions of the affected communities. Avoiding accusations of land grabbing thus requires from companies a great deal of legitimization work (Kish & Fairbairn Reference Kish and Fairbairn2017; Li Reference Li2014; Maiyo & Evers Reference Maiyo and Sandra2020; Salverda Reference Salverda2018).

How, then, do agribusiness companies achieve the four interrelated tasks of gaining state support, obtaining a concession, asserting continued land control, and fostering acceptance?Footnote 4 This article makes two central points. First, it argues that to articulate their claims and maintain a positive image, business actors engage in a range of performances, which, taken together, form their repertoire of control. Second, it contends that to ensure land control amid delays and complications, companies must additionally exhibit a capacity for what I call “corporate polyphormism,” that is, the ability to adapt their performances to shifts in the actions and reactions of state officials, local residents, as well as activists and journalists.

This article examines the changing repertoire that one agribusiness venture has deployed to gain and regain land control in the Senegal River Valley and Delta from 2010 onward. This company has undergone repeated transformations. Originally set up as Senethanol in the rural community of Fanaye, it became Senhuile-Senethanol in 2011 upon agreeing to a joint venture with the Tampieri Financial Group.Footnote 5 Due to local infighting, President Abdoulaye Wade relocated the project to the Special Avifauna Reserve of Ndiaël (the Reserve). The company was eventually renamed again, to Senhuile. Currently, it operates as Les Fermes de la Teranga.Footnote 6 Despite obtaining a new concession in the Reserve, managerial, financial, and political problems have undermined the company’s ability to cultivate the land, and to date, the project remains in limbo.Footnote 7

The agribusiness venture analyzed here is one of the “emblematic projects” of the global land rush (GRAIN 2018) that has caused public outrage and received heightened attention from Senegalese and foreign researchers. These studies mostly center on community responses to and local impacts of the project (e.g. Benegiamo & Cirillo Reference Benegiamo and Cirillo2014; Gagné Reference Gagné and Bartley2019; Koopman Reference Koopman2012; Prause Reference Prause2019). This article adopts a different analytical angle. It examines not only the pivotal role of the national state in governing land deals (Wolford et al. Reference Wolford, Borras, Hall, Scoones and White2013) and “political reactions from below” (Borras Jr. & Franco Reference Borras and Franco2013:1725), but also how corporate land claimants adapt to a shifting and contested domestic environment. In particular, it assesses how the relationship between the central government, the local populations, the civil society, and the company has influenced the company’s repertoire of control over time and place.

This study is based on in-depth field research in Senegal conducted over two years between 2013 and 2018, during which I investigated seven foreign and domestic farmland investments. It draws on an analysis of hundreds of pages of corporate materials, government documents, private correspondence, and media reports related to the company discussed here; on qualitative interviews with more than one hundred stakeholders such as administrative authorities, high-ranking state officials, business executives, municipal councilors, and villagers; and on political ethnography in various institutional settings and in rural areas.Footnote 8 Return trips to previous fieldwork sites allowed me to observe the company’s changing land-control strategies and the evolving opinions of state agents and local actors.

In this article, I first review the relevant literature on land deals and introduce the conceptual apparatus employed here. Following a chronicle of the case study’s trajectory in Senegal, I then discuss the main performances the company has used to (re)gain and sustain land control, influence the Senegalese government, and soften local opposition. To conclude, I consider the broader significance of my arguments for agrarian change in Africa.

Repertoires of Control and Corporate Polyphormism

Several scholars argue that to acquire land, companies are prone to exploiting weak governance structures, disregarding official procedures, and neglecting to properly consult local populations (e.g. Alden Wily Reference Alden Wily2011; Deininger Reference Deininger2011; Li Reference Li2014; Nolte & Väth Reference Nolte and Väth2015). In many African countries, indeed, the lack of clear guidelines regulating land investments leaves ample room for these kinds of legal manipulations.

However, these perspectives overlook two important realities. First, despite their interest in promoting private investment in agriculture, host governments do not systematically defer to companies but seek instead to negotiate “the costs and benefits of the contemporary moment” (Wolford et al. Reference Wolford, Borras, Hall, Scoones and White2013:192; see also Burnod et al. Reference Burnod, Gingembre and Ratsialonana2013; Schlimmer Reference Schlimmer2019). In Africa, most land projects do not take place on privately owned land but on public land managed by state institutions (Alden Wily Reference Alden Wily2011), thus increasing the reliance of land-seeking investors on the goodwill of government actors. Over time, though, many governments have become more vigilant because of mounting project failures and widespread opposition to land deals (Cotula Reference Cotula2013). Multiparty democracies with a relatively strong civil society, such as Senegal, may be more responsive to resistance movements that challenge land deals and, by the same token, their electoral legitimacy (Gagné Reference Gagné and Bartley2019). However, African states with authoritarian tendencies such as Tanzania, Cameroon, and Ethiopia have also recently severely criticized inefficient investors or terminated unproductive land projects (Chung Reference Chung2020; GRAIN 2018; Dejene & Cochrane Reference Dejene, Cochrane, Cochrane and Andrews2021). Wherever they operate, companies must therefore actively cultivate state support to obtain and retain land.

Second, land control over large areas implies exerting power over local populations (Chung Reference Chung2020; Millar Reference Millar2018), an undertaking that is not as straightforward as it may seem. Power is a relational process. It can take different forms, ranging from outright coercion to more refined modalities of authority, influence, force, and manipulation (Bachrach & Baratz Reference Bachrach and Baratz1970). A key facet of power consists of shaping “perceptions, cognitions and preferences” to forestall the formation of grievances (Lukes Reference Lukes2005:28). The diverse forms of power are reflected in the manifold strategies employed by land investors in their relations with local populations, ranging, for instance, from the use of physical force to keep resistance in check, to the provision of training programs for generating alternative sources of income, to promises of financial compensation for the loss of land (Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Campion and Gasparatos2017; Chung Reference Chung2020; Millar Reference Millar2018). These strategies are unevenly successful, as people can not only resist land companies but also try to further their own interests when partaking in these projects.

This article advances the nascent literature that looks at the strategies that agribusiness companies utilize to survive against adversity. Just as protestors devise “repertoires of contention” to press claims on superiors (Tilly Reference Tilly2006), and government or economic actors develop “repertoires of domination” to maintain their dominance relative to others (Poteete & Ribot Reference Poteete and Ribot2011), investors need to deploy their own “repertoire of control.”Footnote 9 I conceptualize repertoires of control as the array of “claim-making performances” (Tilly Reference Tilly2008:xiii) that companies use to acquire and retain land as well as to influence host states, local populations, and the public at large. Performances, which Erving Goffman conceives of as “techniques of impression management” to convey an image of oneself to a particular audience (Reference Goffman1959:208), are inherent to social life.Footnote 10 As Goffman observes, actors are not necessarily cynical or dishonest; they are in fact often sincerely convinced by their own performance. But these “claim-making performances” are not solely a matter of appearances. They serve to establish, preserve, or enlarge the power of the people who execute them (Poteete & Ribot Reference Poteete and Ribot2011).Footnote 11 They can also help actors resist or evade assertions of power by other contenders.

Through “creativity and improvisation,” actors can amend and enhance their repertoires to take advantage of new circumstances (Poteete & Ribot Reference Poteete and Ribot2011:446; see also Tilly Reference Tilly2006, Reference Tilly2008). This ability is crucial for investors, given that land obtention and retention constitute highly dynamic and volatile processes, rather than one-off transactions. Agribusiness companies are likely to “enact” (Welker Reference Welker2014) their repertoires of control differently when their management teams change, as various people gauge the potentialities and risks of their environment in diverse ways. It is thus more analytically fruitful to view corporations as “multiply authored,” “composite,” and “permeable” to outside influence (Welker Reference Welker2014:4-5), instead of as cohesive, unified, and determinate behemoths, as they are often implicitly characterized in the literature.

An analogy with the mechanisms of evolution in the living world offers another apt way to understand changes in land-control strategies. I frame the capacity of agribusiness companies to adapt as “corporate polyphormism.” Polymorphism, a concept borrowed from biology, refers in broad terms to the ability of organisms to adjust physiologically, morphologically, or behaviorally to modifications in their external environment (Bregliano Reference Bregliano2018). The notion of “corporate polyphormism” encapsulates the capacity of business actors to not only switch their emphasis from one strategy of control to another, but also to alter the way they perform a given strategy when faced with new situations.

In brief, examining land deals through the prisms of repertoires of control and corporate polyphormism allows us to perceive how different agribusiness executives and employees, at different moments, resort to multiple claim-making performances to control land and influence other stakeholders.

From Senethanol to Les Fermes de la Teranga

The land deal studied here took place in a moment of renewed interest in agriculture by the administrations of both Presidents Abdoulaye Wade (in power from 2000 to 2012) and Macky Sall (2012 to the present). Their vision of agribusiness as a lever for economic development ushered in various incentive programs, policies, and measures. Although this project occurred in a favorable investment climate, the company has had a fraught trajectory. It has gone through five main phases, during which its name, business mission, management team, ownership, and location changed in whole or in part.

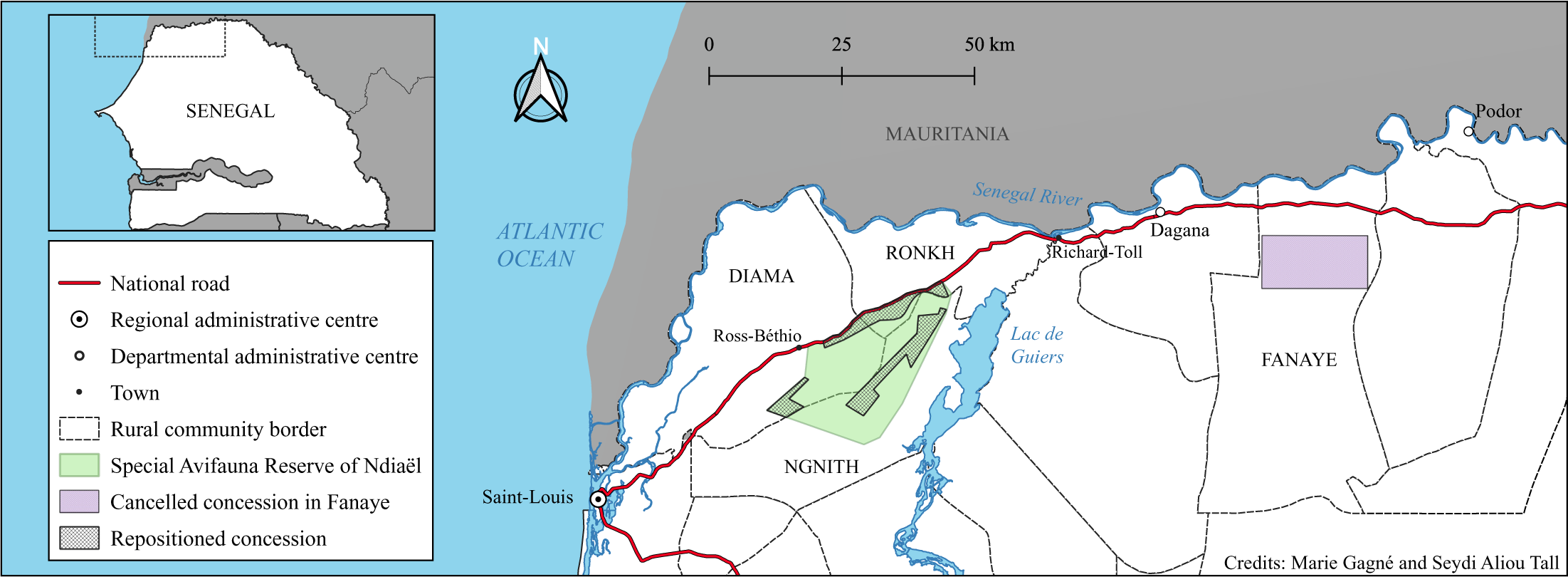

The first phase started in July 2010, when “an Israeli-born and Brazilian-naturalised businessman” (CRAFS et al. 2013:3) created Senethanol.Footnote 12 Another Senegalese investor also acquired a minority stake in Senethanol and became chairman of the board of directors. The company intended to grow sweet potatoes on 20,000 hectares of land in Fanaye, a rural community located in the Senegal River Valley (see Figure 1), and then to process their harvest into ethanol for domestic and foreign markets. This phase was brief: the company obtained land from Fanaye’s rural council in June 2011, but did not start farming.

Figure 1. The company’s concessions in Fanaye and the Special Avifauna Reserve of Ndiaël.

The project then entered its second phase. In July 2011, Senethanol and Tampieri Financial Group, an Italian company, announced they had formed Senhuile-Senethanol. The new partnership entailed considerable modifications to the project, which thereafter aimed to farm sunflower seeds for Tampieri’s oil-processing facilities in Italy and use the crop residues to produce ethanol in Senegal. However, community divisions, fueled both by political motivations and substantive concerns about the project’s impacts, culminated in two deaths and numerous injuries during brawls in October 2011 (Gagné Reference Gagné2021; IPAR 2012). The local strife cast Wade in a bad light a few months before the 2012 presidential elections, persuading him to terminate the project in Fanaye.

However, only a few days after President Wade suspended the venture in November 2011, he instructed the Ministers of Agriculture and the Interior to find an alternative site for Senhuile-Senethanol.Footnote 13 In the end, the state decided to relocate the project to the Special Avifauna Reserve of Ndiaël, a protected area in the Delta of the Senegal River (see Figure 1). This site was chosen specifically because it is not managed by rural councils (as most land in the country is), but instead belongs to the forest domain of the state.

The Reserve is situated within the rural communities of Ronkh, Ngnith, and Diama, where Wolof, Fulani, and Moorish people live. Traditionally, Wolofs primarily practice agriculture, while Fulani and Moorish people are herders, but all three groups combine farming with cattle breeding to varying degrees. The decree that created the Reserve in 1965 recognizes the right of the surrounding communities to collect dead wood, harvest forest foodstuffs, and graze their animals in the Reserve, but forbids hunting, agriculture, and tree felling. Although the decree prohibits the establishment of human settlements within the Reserve, the state has not displaced existing villages and hamlets.

Even before Senhuile-Senethanol started its activities in the Reserve, the project was met with disapproval. When, in December 2011, a government delegation informed people about the forthcoming arrival of the company, residents of Ngnith, Ronkh, and Diama denounced the project with one voice in the media and communicated their disquiet in writing to the state (APS 2012; Benegiamo & Cirillo Reference Benegiamo and Cirillo2014).

Despite local opposition, Wade hastened to authorize the relocation of the Senhuile-Senethanol project. Wade, who had lost the first round of elections on February 26, 2012, issued the authorization just five days before the run-off (which was scheduled for March 25, 2012). In allotting land to the company, the state extinguished the customary rights of common pasture and overturned the ban on agricultural activities in the Reserve.

During his electoral campaign, opposition candidate Macky Sall had promised to stop the project. After winning the election, President Sall kept his promise and abrogated Abdoulaye Wade’s decrees through a third presidential decree enacted on April 12, 2012. Just four months later, however, Sall reconsidered his decision and reapproved the project, which then embarked on its third phase.

After the company began its farming activities in August 2012, community opinions regarding the project evolved in multiple directions, partly due to state pressures and Senhuile-Senethanol’s strategy of cooptation (as discussed below). Some herders have since grudgingly adapted to the presence of the company or even actively collaborated with it in the hope of deriving personal and/or community benefits.

Yet, the company was never able to garner the consent of a sizeable number of pastoralists, who see the plantation as a threat to their livelihoods and ways of life. Project opponents formed the Committee for the Defense of the Ndiaël Avifauna Reserve (Collectif pour la défense de la Réserve d’avifaune de Ndiaël [CODEN]) and have carried out a sustained campaign, with the help of national and foreign CSOs, to expel the company from the Reserve (Benegiamo & Cirillo Reference Benegiamo and Cirillo2014; Gagné Reference Gagné and Bartley2019; Prause Reference Prause2019). CODEN includes rural councilors, village chiefs, local leaders, and community members, most of whom belong to the Fulani ethnic group.

A fourth turning point in the trajectory of the company occurred when it abandoned the farming of sunflower seeds for exports and started to cultivate maize, rice, and groundnut seeds for the local market. Around this time, the company’s name was shortened to Senhuile. In April 2014, Senhuile dismissed the foreign founder of Senethanol for alleged misuse of corporate assets and replaced him with an Italian CEO who was tasked with fixing the business. The company also hired a social responsibility manager to mend fences with the local populations and to coordinate what was internally referred to as an “emergency communication intervention” provoked by an international petition targeting the Tampieri Financial Group in Europe.Footnote 14

A change in ownership marks the fifth and most recent phase of the company. Because of enduring financial and operational difficulties, Tampieri Financial Group pulled out of the project in 2017 and sold their shares to their Senegalese partner. With the arrival of new investors in 2018, Senhuile became Les Fermes de la Teranga, which translates into English as “The Farms of Hospitality.”Footnote 15 Until recently, the company had scarcely cultivated a single hectare, but it was reported that it did in fact farm some rice in 2021.

The Company’s Changing Repertoire of Control

To ensure the resumption and survival of its agribusiness project, to remain on good terms with the Senegalese state, and to neutralize opposition, the company has adopted an elaborate repertoire of interconnected claim-making performances. It has employed some of these strategies simultaneously, while others were added, modified, or abandoned over time, as external circumstances evolved and as new staff with different visions and objectives joined or left the business.

Figure 2 shows that the company made ambitious promises of socio-economic development and adapted its business activities to changing state priorities. Senhuile-Senethanol also cleared the forest rapidly to physically secure and control its land concession, a strategy that generated community backlash. Partly as a response to rising discontent, it conducted after-the-fact consultations and adopted a dual tactic of cajoling supporters while coopting, ignoring, or repressing opponents. Furthermore, the company mounted a vast public relations campaign to advertise its intended contribution to state programs and cultivate an “idealized version” of itself (Goffman Reference Goffman1959:48). Since the Italian shareholders left the project in 2017, however, the company has adopted a more discrete attitude while continuing to sublease part of its concession in order to retain land control.

Figure 2. The company’s changing repertoire of control.

Ambitious Promises of Development

Ambitious promises constituted a key component of the company’s repertoire of control. From the beginning, Senethanol acted as a benevolent sponsor of development to encourage its acceptance by the government and the population in Fanaye, a role that agribusiness and mining companies often adopt in Africa, as elsewhere (e.g. Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Campion and Gasparatos2017; Maiyo & Evers Reference Maiyo and Sandra2020; Welker Reference Welker2014).

After it lost land control in Fanaye and relocated to the Reserve, Senhuile-Senethanol significantly inflated the scope of its promises compared to what had been planned in previous iterations of the project. The revamped projections included investments of XOF 137 billion (around USD 257 million) instead of the 97 billion (USD 207 million) formerly announced, as well as the creation of 6,000 to 10,000 direct and indirect jobs (an increase from the 3,500 to 4,000 initially promised) (Diop Reference Diop2012; Kane Reference Kane2011; Mbodj Reference Mbodj2012; Sylla Reference Sylla2012).Footnote 16

Other promises made by the company in Fanaye or the Reserve include the creation of two electric plants in rural areas; the annual payment of XOF 800 million (USD 1.5 million) to municipal councils; the production of biofuels from algae; the construction of a milk-processing plant; the building of fifteen schools and a sports center; the provision of 300 km of irrigation canals to villages; and the development of a national network of agricultural machinery rental centers (Bombolong Reference Bombolong2012; Diagne Reference Diagne2012; Kane Reference Kane2011; Ndiongue Reference Ndiongue2012).

These promises convinced Presidents Wade and Sall, as well as their political entourages, to back the project. Under Wade’s presidency, a deputy from Ronkh, whom the Ministry of Interior had contacted to find a new location for the company, was charmed by Senhuile-Senethanol’s proposed contributions to local development. Eager to bring the project to his home region, he suggested moving the company to the Reserve.Footnote 17 Wade, who wanted to keep the company and its intended investment in Senegal, adopted the idea despite the reluctance of several ministers, deputies, and administrative officials and despite the fact that it would potentially compromise international funding to restore the Reserve’s environment.Footnote 18

The company’s promises also eventually appealed to Macky Sall. After his election, President Sall probably decided to terminate the Senhuile-Senethanol project to mark a rupture with his predecessor. Not long after, however, the Senegalese CEO approached Prime Minister Abdoul Mbaye (in office from April 2012 to September 2013) to explain the company’s ambitions and to restart the project. The Prime Minister and other state officials close to him were seduced by Senhuile-Senethanol’s international profile, business mission, and stated goal to invest USD 257 million—an enormous sum for Senegal.Footnote 19 The government visibly concluded that it could not really dispense with such a major foreign investment.Footnote 20

To legitimize its presence in the Reserve after the resumption of the project, the company continued to present itself as a “corporate citizen,” whose business would benefit local residents and the entire country. Senhuile is “a development project,” claimed one Senegalese executive in a local newspaper (Lo & Fall Reference Lo and Fall2013). The CEO of Tampieri Financial Group similarly declared to an Italian journalist, “We are doing something useful for the local population and for all of Senegal, helping them to produce the food they need” (Stella Reference Stella2014). The then-CEO of Senhuile likewise said the company aimed to distinguish itself as no less than the “primary actor of the national economy” (Senenews Reference Senenews2015). However, despite its efforts, the company has not fulfilled most of its promises related to energy provision, job creation, and agricultural production.Footnote 21

Alignment With State Priorities

The most obvious indication of the company’s capacity for polyphormism (and also one of the most important strategies of its repertoire) has been to align its business mission with government priorities in a bid to retain support. This strategy was already visible at the start of the project in Fanaye. The businessman who founded Senethanol had wanted to create an agricultural project in the Senegal River Valley since the 1990s. Wade’s accession to power and eager interest in biofuel production, in conjunction with a growing global demand for alternative sources of energy, provided the impetus for bringing his company into being.Footnote 22 When I asked where the inspiration for his project came from, the businessman replied that he had designed it in response to the Senegalese “head of state’s call” to produce biofuels.Footnote 23

Senhuile devoted even more effort to conforming with state objectives after President Sall reinstated its project in the Reserve in 2012. The Sall government, which has moved away from the biofuel sector heavily promoted by Wade and has instead made rice self-sufficiency a top priority to be achieved by 2017, hoped that Senhuile would help realize national agricultural ambitions. In exchange for backing the Senhuile project, the government enrolled Senhuile in its efforts to boost the production of rice (as well as of groundnut seeds and maize) for the local market, as announced by the chameleonic company in March 2013. Because Senhuile depended on the state for land access, the government was able to monitor the company’s agricultural operations closely (Lo & Fall Reference Lo and Fall2013). Until approximately 2014, a committee within the Senegalese Prime Minister’s office even conducted field missions in the Reserve to supervise Senhuile.

Although both Senhuile executives and state agents claimed that the company started to farm these crops at the request of the Senegalese government, the change represented a convenient convergence of interests for different reasons.Footnote 24 First, the primary goal of the Tampieri Financial Group in doing business in Senegal was to source sunflower seeds at more predictable and controllable costs for its oil-processing plants in Italy. However, after global food prices had peaked in 2008 and 2011, they started to decline again, thereby making it more affordable to buy seeds on international markets.Footnote 25 Second, several patches of land in the Reserve concession were discovered to be too saline for sunflower farming. To leach the salt away, the company decided to cultivate rice, a crop that requires flooding the land, after which it planned to go back to growing sunflower seeds (Synergie Environnement 2013). Third, the former CEO of Senhuile reported that the seeds produced in Senegal did not comply with Tampieri’s quality standards. Producing sunflower seeds therefore appeared less advantageous to the Tampieri Financial Group.Footnote 26 As the original plan was not working terribly well anyway, the company thus transformed an unfavorable situation into an occasion to publicly back state objectives for food security (Fall Reference Fall2017). In yet another instance of claim-making performance, the company pledged to produce 30,000 tonnes of rice within two years to contribute to the National Program of Rice Self-Sufficiency (Diagne Reference Diagne2015).

The company similarly professed its support for essentially all the programs the Senegalese government has espoused in recent years. For instance, Senhuile claimed its business activities would help attain the goals of the Plan for an Emerging Senegal—the government’s main policy framework for promoting economic growth since 2014—as well as the National Strategy for Economic and Social Development and the Program to Accelerate the Pace of Agriculture in Senegal (Diagne Reference Diagne2015; Le Soleil 2015). Despite attempts by the company to embrace government aspirations, most state officials I met reported their dissatisfaction with its concrete achievements several years after the project’s inception.Footnote 27 With its new emphasis on discretion (discussed below), Les Fermes de la Teranga no longer pretends to meet government priorities.

“Land Conquest” Strategy

At the beginning of its third phase in 2012, it was decided that Senhuile-Senethanol would not displace pastoral populations from the Reserve but instead leave them on site (contrary to the provisions of Wade’s decree, which had set apart 6,550 hectares of land for their possible resettlement). This modification seemingly stemmed from staunch local opposition as well as from the Sall administration’s concerns about displacement. Even though the company has allowed residents to remain in the Reserve, it has also attempted to spatially occupy and cordon off its concession, thereby performing the role of a responsible but rightful land claimant.

In the short term, the company’s strategy for cohabiting with the herders was to create livestock corridors so that animals could access water points and pastures outside the concession, as well as to cultivate plots no closer than 500 meters to villages and 300 meters to hamlets (Diagne Reference Diagne2012; Synergie Environnement 2013). Although this policy appeared to respect the right of the local people to remain in the Reserve, the company’s fields and irrigation canals effectively encircled some villages, cut off roads, and severely reduced the area available for pasture. In the long term, the company aimed to end nomad pastoralism through intensive husbandry and sedentariness and, by so doing, to diminish competition for land while also aligning with the government’s emphasis on modern cattle breeding.Footnote 28

Despite its commitment to avoiding resettlement, the company was intent on staking out its claim to the land. Once the project resumed in the Reserve in August 2012, Senhuile-Senethanol embarked on what one senior manager of the company called in our interview a “land conquest” strategy. Through this strategy, it sought to create vast contiguous fields and establish control over its newly acquired territory (Fall Reference Fall2017). In less than two years, the company deforested at least 5,000 hectares to signal its presence to neighboring communities.

However, the “inscribing of boundaries” to make the land “investible” (Li Reference Li2014:589) led to skirmishes between farm employees and people living in the Reserve. The first violent incident was reported on September 9, 2012 (Bombolong Reference Bombolong2012), only one week after Senhuile-Senethanol had started clearing the land. Other confrontations followed, among them incidents on October 31, 2012, February 1, 2013, and June 6, 2013, as well as acts of arson on March 2, 2013 (Benegiamo & Cirillo Reference Benegiamo and Cirillo2014; Diop Reference Diop2013; Diop Reference Diop2014; Nettali 2013). To protect its agricultural installations against vandals and stray animals, Senhuile-Senethanol hired security personnel equipped with dogs and fenced its fields with barbed wire.

The government’s ambivalent stance fundamentally influenced the company’s capacity to control land. On the one hand, the government made concessions to assuage popular grievances against the investment. Most notably, the Sall regime decided to downsize Senhuile-Senethanol’s plantation from 20,000 to 10,000 hectares as early as August 2012, in the wake of discussions with community representatives (APS 2012).Footnote 29 Because of its location on state-controlled land, the company was vulnerable to the demands of its benefactor. When I asked about the government’s decision to scale back the size of the concession, Senhuile’s chairman simply replied, “The land belongs to the state. If it says to leave, we have to shrink [our plantation].”Footnote 30

The Sall administration also repositioned the plantation, which, according to Wade’s decree, was supposed to be located entirely within the rural community of Ngnith. In preparation for the arrival of Senhuile-Senethanol, the Wade government had drawn a map that included only five villages, instead of the thirty-seven villages and hamlets that Ngnith contains, a glaring omission that angered community members.Footnote 31 In September 2012, however, the Sall government crafted a more comprehensive map and decided to partition Senhuile-Senethanol’s concession between Ngnith, Ronkh, and Diama to avoid enclosing any villages and to circumvent opposition from the Ngnith community (see Figure 3).Footnote 32

Figure 3. Senhuile-Senethanol’s repositioned concession in the Special Avifauna Reserve of Ndiaël.Footnote 33

On the other hand, the government stationed the gendarmerie in the Reserve to aid Senhuile-Senethanol in its land conquest strategy and quell protests in Ngnith and Ronkh, where the company has concentrated its activities. Gendarmes guarded the site for about nine to twelve months between 2012 and 2013, an extraordinary measure in a region where the population is accustomed to agro-industries.Footnote 34 Clashes between project opponents and the police force led to the use of tear gas by the gendarmes, people wounded on both sides, and imprisonments. To discourage inquiries by critical outsiders, the gendarmerie also interrogated at least two foreign correspondents who were touring the Reserve with local project opponents in 2013.Footnote 35 While they have periodically intended to take to the streets or disrupt official political events, CODEN members have been deterred from executing their plans by administrative agents or the police.Footnote 36 In October and December 2012, President Sall also personally met Ngnith and Ronkh village chiefs to convince them to accept the project.

The threat and application of force, both by the gendarmerie and by the company’s private security guards, served to exert power over the people. The imprisonment of those who rejected the Senhuile-Senethanol project instilled fear in the population and incited many to refrain from overtly opposing it. Power over the bodies and minds of the people induced compliance on the part of numerous community members, who felt obliged to condone a project imposed by the state, which they viewed as “stronger” than they are.Footnote 37

After-the-Fact Consultations

The company’s repertoire of control was not solely based on force but also included pacification mechanisms. Before starting its operations in the Reserve, Senhuile-Senethanol had made verbal promises to residents to demonstrate its attentiveness to their needs and enlist their support. It also conducted ad hoc negotiations in Dakar with project opponents. The company eventually formalized some of its promises through what were framed as consultative processes that seemingly aimed at making up for the Senegalese government’s own failure to seek free, prior, and informed consent from those living within the Reserve.

The first incarnation of this strategy was Senhuile-Senethanol’s community hearings in the context of its environmental and social impact assessment. From November 30 to December 18, 2012, a consulting firm hired by Senhuile-Senethanol conducted ten meetings to register local views on the project (Synergie Environnement 2013). These meetings primarily took place in Ronkh; Ngnith villagers reportedly refused to participate (Benegiamo & Cirillo Reference Benegiamo and Cirillo2014). The firm released its final report, which contains a series of mitigation measures and community promises, in October 2013. However, the fact that Senhuile-Senethanol carried out this assessment after its arrival in the Reserve (in contravention of Senegalese law, which requires such an assessment prior to commencing activities) suggests that the whole exercise aimed as much at legitimizing Senhuile-Senethanol’s establishment ex post facto as at ensuring its compliance with existing regulations.

The second incarnation came with the government’s request to appease community tensions.Footnote 38 Responding to this request in January 2014, the company, which was then going by the name of Senhuile, signed two memorandums of understanding (MoU) with its community brokers from Ronkh and Ngnith (discussed in the following section). The two identical MoUs contain promises such as creating livestock corridors, developing farmland for the local populations, respecting the right of residents to circulate freely in the Reserve, and fencing cemeteries located within Senhuile’s plantation (République du Sénégal 2014). The MoUs provide that, in return, populations would shield Senhuile against straying livestock, inform administrative authorities of any public demonstrations against the project, and protect the company’s agricultural equipment and fields against vandalism.

Although these MoUs convinced several erstwhile opponents to endorse Senhuile, they suffer from limitations in terms of representativeness, content, and enforcement modalities.Footnote 39 First, Senhuile chose those who signed on behalf of the Ronkh and Ngnith populations, and CODEN members from Ngnith asserted that their signatory was not their legitimate representative.Footnote 40 Furthermore, only those villagers with opinions favorable to the company were apparently involved in drafting the MoUs.Footnote 41 Second, the rural council president in Ngnith reported that the promises recorded in the document were significantly smaller than what the company had pledged verbally, and many Ronkh and Ngnith residents viewed the agreement as unsatisfactory.Footnote 42 Third, while the MoUs stipulate that failure by the populations to respect their commitments will “be automatically referred to the competent administrative authorities for settlement” (République du Sénégal 2014:3), it does not include explicit mechanisms for appeal if the company does not comply with its own promises (Fall Reference Fall2017).

These MoUs, negotiated and adopted under the government’s auspices, were in essence meant to ensure that Senhuile could pursue its operations without further opposition. People within the company had mixed opinions on these MoUs. For one former Senegalese executive, who proudly read aloud clauses of the MoUs during our conversation, these were not repressive or disingenuous instruments but rather a way to offer local populations the occasion to formulate their requests and ensure that the company would fulfill its promises.Footnote 43 However, although the architects of the MoUs saw them as an accomplishment, the staff in charge of implementing them thought they were impracticable. To convey that the company had set overambitious goals, one corporate executive who was not involved in drafting the MoUs exclaimed, “They signed a ridiculous memorandum of understanding according to which Senhuile would do more than the Senegalese government!”Footnote 44

The company kept a number of its promises, such as constructing a sewing center, distributing notebooks to pupils, and offering free medical consultations, thus alleviating popular discontent. To ingratiate the company with the local populations, the first CEO also hired surplus staff, a practice a former executive described as “hiring of complacency” (“embauches de complaisance”).Footnote 45 For instance, Senhuile deliberately employed daily workers to clear the land instead of using machinery (Diop Reference Diop2013). Since job opportunities constitute an important issue for the people, this strategy helped Senhuile earn support.

But in the end, the company has been unable to achieve several, if not most, of its promises. As hiring more staff than needed was fundamentally incompatible with the goal of realizing profits, in 2014 the new Italian CEO started to dismiss employees to reduce wage costs, thus angering many company supporters. Perhaps, in making these promises, the company’s management team was well-meaning and genuinely committed to social betterment. At a minimum, there is no evidence that they intended to deceive the local populations. Nevertheless, the ratification of the MoUs allowed Senhuile to claim it had “buried the hatchet” with its opponents (La Signare 2014) when, in fact, many community members continued to reject the project.

Cooptation and Sidelining of Local Opponents

In reaction to popular disgruntlement at the onset of the project in the Reserve, the company coopted community leaders who could wield influence over other villagers, a strategy that has contributed to splitting the local opposition. For instance, in 2012, Senhuile-Senethanol obtained the support of a religious leader from the area, thereby inducing a village chief from Ronkh, who hitherto disapproved of the project, to become one of its principal advocates.Footnote 46 A company executive also convinced one of the most vocal leaders of the opposition movement in Ngnith to leave CODEN and endorse the project.Footnote 47 These two individuals were appointed presidents of two Collectifs that the company created to counterbalance the influence of CODEN, ratify its MoUs, and liaise with the population. One of them also worked for the company. To ensure their loyalty, Senhuile offered incentives to its brokers, such as paid trips to Mecca or the construction of a Koranic school in their village.Footnote 48

Although the company made community-wide promises of development, it in fact primarily provided benefits to people living right next to its fields, in particular those who publicly stood behind it and therefore helped it maintain the image of a charitable actor. For instance, it funded women’s gardens in three villages whose chiefs backed Senhuile. Some of my interviewees also asserted that the company primarily hired people from pro-investment villages. The community development measures thus became instruments to reward support for the company instead of compensating villagers for the plantation’s detrimental repercussions. In return, the near-systematic participation of these brokers and allies in Senhuile’s frequent public relations events allowed the company to claim evidence of local approval without having to establish a good rapport with the entire community.

In contrast, the company tended to belittle the concerns of local people who refused to cooperate. The situation improved upon the hiring of the community liaison officer in 2014, but this was insufficient to completely deflect opposition. To this day, numerous inhabitants of villages located south of the Reserve in Ngnith, who have larger herds and rely more heavily on cattle rearing for their subsistence than people living in Ronkh, remain firmly opposed to the project. Operating from the twin premises that traditional pastoralism is not economically viable and that the project is beneficial for the populations, several company executives have disregarded the fears of project opponents. For them, people hostile to the project are “against the development of Senegal,” animated by personal interests, or manipulated by civil society leaders.Footnote 49 Mutual distrust and ongoing local resistance have weakened the capacity of the company to lay legitimate claims to the land without, however, deterring it from continuing its project.

From Extensive Public Relations Efforts…

To justify the enclosure of 20,000 hectares for its sole benefit, the company supplemented its promises of development with extensive public relations activities. After the deaths of two villagers in Fanaye in 2011, journalists in Senegal and Italy started to denounce Senhuile-Senethanol, prompting it to defend its activities in the media (e.g. Calzolari Reference Calzolari2011; Kane Reference Kane2011). The company intensified this sort of claim-making performance when it entered its third phase in the Reserve and increasingly received unflattering attention from Senegalese and international CSOs. It staged numerous public events, tours of the plantation, and media interviews to highlight its achievements and broadcast its supposed acceptance by the population. These events, attended by ministers, administrative agents, local elected officials, and community leaders, tapped into a typically Senegalese propensity for ceremonial festivities and signaled to the public that the government supported the company.

More fundamentally, Senhuile turned the fulfillment of its MoU pledges and other promises into occasions to cultivate an image of corporate responsibility toward the communities. For example, the company set up annual ceremonies to open its harvested fields for cattle to graze crop residues, events to which it repeatedly invited the national press. This customary practice, called in French vaine pâture, is ubiquitous in the area. But through the “ceremonialization” of vaine pâture and fodder distribution, Senhuile attempted to present a rather unexceptional event as an illustration of its generosity.

This type of performance morphed in new directions after the foreign businessman who had created the company was terminated and prosecuted for misappropriating funds in 2014. The Italian shareholders had thus far largely delegated the maintenance of their corporate image to the Senegalese staff. At this juncture, the new management team increased their self-promotion efforts, acknowledging past mistakes to convince the public of their new and reformed character. These efforts were also a response to the changing approach of local and international CSOs that opposed the project. Whereas these CSOs had earlier singled out the management team and political authorities in Senegal, they now started pressuring the Tampieri Financial Group in Italy to withdraw from the venture.

One example of this amended strategy is when the first Italian CEO consented to appear in a 2015 French documentary on land grabbing in Africa, in which he offered to meet the most prominent leader of CODEN (an invitation the leader declined). Moreover, the company agreed to meet with two international CSOs critical of their activities who had vainly requested an audience in the past and to reply to two calls for explanation by the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre.Footnote 50 To underscore the company’s collaborative relations with neighboring communities, the newly hired social responsibility manager also frequently posted pictures on social media of Senhuile’s philanthropic actions. Transparency and conciliation efforts meant to restore the company’s tarnished reputation reduced local animosity toward Senhuile, at least momentarily.

…to Cautious Discretion

Since the departure of the Tampieri Financial Group in 2017, however, the company has become far more discreet, if not secretive, about its business. This transformation is a prime example of corporate polyphormism, partly made possible by the state’s declining interest in the company. The company’s current attitude might reflect a decreased financial capacity to maintain public relations activities at previous levels, an attempt to distance itself from Senhuile’s controversial reputation, or an expression of the new owners’ inclinations.

While the new strategy is probably attributable to some combination of these reasons, several signs denote a deliberate withdrawal from public scrutiny. Around April 2017, Senhuile shut down its website, which featured positive news stories, pictures of an audience with President Sall and of accomplishments in neighboring communities, and institutional documents to show it was in good standing. Since its change to Les Fermes de la Teranga, the company has largely ceased organizing media events.Footnote 51 At my last visit to Senegal in 2018, it had moved its headquarters from a luxurious downtown building to a small anonymous office in a residential neighborhood of Dakar.Footnote 52 In our interview the same year, the Senegalese CEO declined to elaborate on the transformation of Senhuile into Les Fermes de la Teranga, seeming displeased that I was informed of the change. Despite the approval of one of the new foreign executives, the CEO also denied my request to meet with the director of operations and the social responsibility manager, stating that they “do not have the authority to represent the company.”Footnote 53 Administrative officials and local supporters of the company, previously knowledgeable about Senhuile, were at the time unclear about the new investor’s identity and business plans.Footnote 54 Even its mid-level executives were not informed about the new company’s managerial functioning and future orientation. Opacity around the project has nurtured rumors about Les Fermes de la Teranga’s genuine motives.Footnote 55 However, the arrival of a new manager might indicate a reversion to earlier public relations efforts in a display of behavioral flexibility. Indeed, a media tour was organized in June 2021 to showcase the benefits the company brings to the community (Ndar Info 2021).

Lending Land to Third Parties

Another recent addition to the company’s repertoire of control consists of lending land to community members. In 2018, Les Fermes de la Teranga did not allow herds to graze on its farmland. The company’s security guards captured animals that wandered into the concession and imposed fines to release them, indicating that it intended to maintain land control, at least over the fields it has developed and equipped with irrigation infrastructure.Footnote 56 But its claims to the land appeared even more tenuous than before, due to the company’s inability to farm it. In response, Les Fermes de la Teranga refined an existing strategy to simultaneously attenuate growing popular dissatisfaction while retaining land control.

In the past, Senhuile allowed residents from Ronkh and Ngnith to cultivate 189 hectares of land for free within its concession (about 0.3 hectares per family, in line with the provisions of the MoUs). However, because they did not have the means to purchase agricultural inputs or did not wish to cultivate the land themselves, many villagers ended up subleasing their parcels to wealthier farmers or hiring laborers, thereby indirectly eroding the company’s authority over the land. In 2018, Les Fermes de la Teranga supplied inputs and services to family farmers through interest-free loans to be repaid after the harvests. The company financed people from a dozen villages to cultivate 176 hectares.Footnote 57 It also allocated 185 hectares to two big farmers from outside the community. It has repeated the exercise of lending land to villagers in 2021 (Ndar Info 2021).

While these arrangements respond to long-standing demands, they also make local people dependent on the company for land access in a region where farmland is insufficient. Considering that neighboring communities have unsuccessfully requested authorization to farm in the Reserve since the mid-1990s, their participation in the scheme implicitly acknowledges the company’s claims to the land. A recent statement by the mayor of Ngnith, who declared during the company’s latest mediatized guided tour, “This land that we cultivate, we do so thanks to the generosity of the new director who runs Les Fermes de la Teranga” (Ndar Info 2021), confirms the local population’s tacit approval. In sum, Les Fermes de la Teranga has sought to control its unfarmed land by letting third parties cultivate a tiny portion of it, although some people continue to dispute its legitimacy. In 2020, for instance, CODEN members decided to farm 300 hectares within the concession of the company without its consent.

Conclusion

At the center of this inquiry is a wider concern with the nature and configuration of power relations between the state, private investors, and agrarian populations in Africa. Understanding how investors forge and negotiate their paths to land acquisition and control clarifies not only how African states engage with the private sector in contemporary times, but also how governments and corporate actors exert power over rural people and land. In this relationship, government officials can force local populations to relinquish their land, but they can also be sensitive to those who resist the claims of business actors.

By questioning the preconceived notion that external investors can grab land at their will, this article reframes our understanding of what some scholars and activists call the “new scramble for land” in Africa (e.g. Moyo et al. Reference Moyo, Yeros and Jha2012). The concept of repertoires proposed here helps identify the myriad forms of power, from the most subtle to the most blatant, deployed for amassing state support, gaining and controlling land, and “securing the consent to domination” of the people (Lukes Reference Lukes2005:109). This article also contributes to the literature by highlighting how corporations need to adapt their morphology in order to endure. Corporations are neither monolithic nor static; they are “living” entities compelled to assume varied forms through their capacity for corporate polymorphism. But considerable performative work is required to project a favorable public image and ultimately assert claims to the land.

I have used evidence from the company now known as Les Fermes de la Teranga to show the protean strategies agribusiness ventures employ to gain land control, exert power over people, and respond to criticisms. The company’s performative repertoire has included ambitious promises of development, continual alignment with state priorities, land enclosure, after-the-fact community consultations, cooptation and sidelining of local opponents, a turn from self-promotion to cautious discretion, and lending land to community members. The company has also indirectly exercised control over neighboring populations through the power of the state. Even though many employees said they were sincerely convinced of the project’s virtues, they have been unable to entirely stamp out opposition.

This company, which has managed to survive for the past ten years despite suboptimal results, epitomizes the type of performative work that is needed to justify and implement large-scale land enclosures. An examination of a land project caught in an “in-between,” indeterminate state—not completely abandoned, yet not fully operational—offers unique insights into the highly contentious processes characterizing agrarian change. This company’s experience is one example of many projects in disarray in Africa that substantiate the contention that acquiring, retaining, and exploiting large-scale landholdings while maintaining corporate acceptability is not as easy as was initially assumed. But companies that enjoy greater economic success and local popularity also continue to engage in varied claim-making performances to preserve their legitimacy (Gagné Reference Gagné2020). Even in Senegal, which many investors view as a favorable business destination, land control over the long term remains uncertain and precarious. Corporate land control, indeed, is a complicated undertaking.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Modou Mbaye for transcribing my interviews, Malick Hamidou Ndiaye for helping me carry out the interviews, and Seydi Aliou Tall for assisting with conducting interviews and interpreting the collected data during and after my fieldwork. My gratitude also goes to Initiative Prospective Agricole et Rurale (IPAR), my host institution in Dakar, for their research guidance and logistical help. Laars Buur, Sébastien Rioux, Michael J. Braun, Alexandre Paquin-Pelletier, Ashley Fent, Robyn d’Avignon, Rebecca Wall, John S. Cropper, Youjin Chung, Amy Poteete, and the anonymous reviewers provided cogent comments on earlier versions of this article. I wish to acknowledge Mary S. Lederer and Meridith Murray for copyediting and proofreading the article. Most importantly, this research would not have been possible without the generous collaboration of several informants in Senegal who agreed to share their time, knowledge, and insights with me. All errors are my own.

Competing Interest

None.