Introduction

Currently, Dermadena Manter, Reference Manter1945 (Lepocreadiidae: Lepocreadiinae) contains three species (Dermadena lactophrysi Manter, Reference Manter1945; Dermadena spatiosa Bray & Cribb, Reference Bray and Cribb1996 and Dermadena stirlingi Bray & Cribb, Reference Bray and Cribb1996), all of which infect the intestine of marine fish. Siddiqi & Cable (Reference Siddiqi and Cable1960) illustrated D. lactophrysi and reported it in Lactophrys tricornis (now recognized as Acanthostracion quadricornis (Linnaeus, 1758)), Lactophrys triqueter and Monacanthus hispidus (now recognized as Stephanolepis hispida (Linnaeus, 1766)), from Puerto Rico. Sogandares-Bernal (Reference Sogandares-Bernal1959) reported D. lactophrysi off the Bahamas, Nahhas & Cable (Reference Nahhas and Cable1964) reported it off Curaçao, and Nahhas & Carlson (Reference Nahhas and Carlson1994) reported it off Jamaica. Nahhas & Short (Reference Nahhas and Short1965) and Overstreet (Reference Overstreet1969) reported D. lactophrysi from Lactophrys quadricornis (=Acanthostracion quadricornis) in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Florida. Machida & Kuramochi (Reference Machida and Kuramochi1999) redescribed but did not illustrate D. spatiosa from Aluterus scriptus off Japan.

The stone triggerfish Pseudobalistes naufragium (Jordan & Starks, 1895) (Tetraodontiformes: Balistidae) is distributed in the Eastern Pacific from Mexico to Chile (Pequeño, Reference Pequeño1989; Bussing, Reference Bussing, Fischer W, Krupp, Schneider, Sommer, Carpenter and Niem1995). It inhabits the neritic zone and can be found in areas with reefs or in shallow waters over sandy bottoms (Bussing, Reference Bussing, Fischer W, Krupp, Schneider, Sommer, Carpenter and Niem1995). It feeds on sea urchins, small crustaceans and molluscs (Humann & Deloach, Reference Humann and Deloach1993).

Here, a new species of Dermadena parasitizing P. naufragium from Northern Peru is described and illustrated. Additionally, molecular analysis was also conducted to determine the phylogenetic affinities of Dermadena species within the family Lepocreadiidae.

Material and methods

Helminth recovery and morphological analysis

One specimen of P. naufragium was collected in January 2019 from the coastal zone of Puerto Pizarro, Tumbes, Peru (3°29′S, 80°24′W), using gillnets. It was euthanized immediately after capture and dissected. The digestive tract was placed in Petri dishes with seawater and examined for parasites with the use of a stereomicroscope. Thirteen trematode specimens were recovered alive from the gut. Digenean specimens for staining purposes were fixed under slight coverslip pressure in 70% alcohol and stored in the same liquid. These specimens were stained with Semichon's acetic carmine. After dehydration using a graded alcohol series, they were cleared with Indian clove oil and mounted as definitive glass slides using Canada balsam. Specimens were examined using a compound Olympus™ BX51 light photomicroscope (Tokyo, Japan) equipped with Nomarski differential interference contrast optics, and drawings were made with the aid of a drawing tube. Eleven specimens were measured unless the number (n) is indicated. Measurements are presented as average values followed by the range in parentheses. All measurements are in micrometres.

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), two specimens were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, critical point dried with carbon dioxide, coated with gold and examined using a JEOL JSM-6390 microscope (Tokyo, Japan) at the Rudolf Barth Electron Microscopy Platform of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute. Type specimens were deposited in the Helminthological Collection of the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (CHIOC) and in the Helminthological and Minor Invertebrates Collection of the Museum of Natural History at San Marcos University (MUSM), Peru.

Molecular and phylogenetic analyses

The samples of DNA were isolated from one worm using the Qiagen QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer's protocol. This DNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the primers described by Sun et al. (Reference Sun, Bray, Yong, Cutmore and Cribb2014), for internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2 rDNA) region as the cycling profile for the PCR.

Amplicons amplified successfully were sequenced using the Big Dye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). The samples were sequenced using an ABI 3730 DNA analyser of the RPT01A subunit for DNA sequencing of the Technological Platforms Network at Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The resulting fragments were assembled into contigs and edited to eliminate ambiguities with the Geneious R9.1 software (Kearse et al., Reference Kearse, Moir and Wilson2012), to provide consensus sequences. These sequences were deposited in the GenBank database under accession number ON008470.

The online PhyML 3.0 software (Guindon et al., Reference Guindon, Dufayard, Lefort, Anisimova, Hordijk and Gascuel2010) was used to reconstruct phylogenies based on the maximum likelihood (ML) approach. The model of nucleotide evolution was selected with Smart Model Selection (SMS), run in PhyML (Lefort et al., Reference Lefort, Longueville and Gascuel2017), using the Bayesian information criterion. Node support was computed by nonparametric bootstrap percentages, with 1,000 pseudo-replications (ML-BP) (Anisimova & Gascuel, Reference Anisimova and Gascuel2006).

Bayesian phylogenetic inferences (BIs) were carried out using MrBayes version 3.2.6 (Ronquist et al., Reference Ronquist, Teslenko and van der Mark2012) in XSEDE using the CIPRES Science Gateway (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Pfeiffer and Schwartz2010). The ITS2 region Bayesian analyses were performed using a single GTR + G model. Markov chain Monte Carlo samplings for each matrix were performed for 10,000,000 generations with four simultaneous chains in two runs. Branch supports in Bayesian trees by Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP) were assessed from trees that were sampled every 100 generations, after removal of a burn-in fraction of 25%.

To elucidate the affinities of Dermadena within Lepocreadiidae, a database was constructed using sequences obtained here plus representative sequences from the species of this family available in the GenBank. Sequences of Neophasis oculata and Neophasis anarrhichae (Acanthocolpidae) were added as outgroup.

Description

Dermadena pseudobalistesi n. sp.

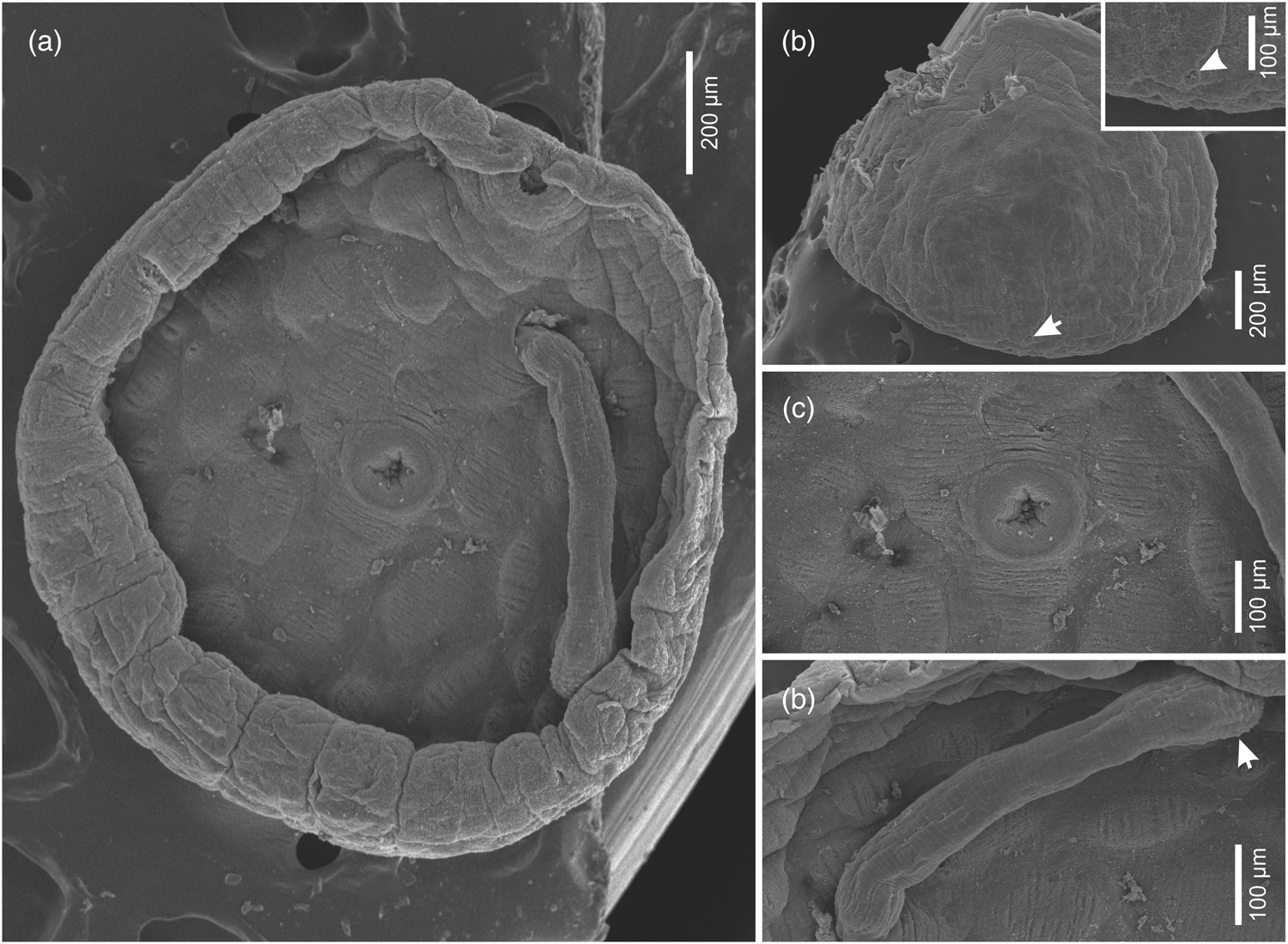

Measurements are in table 1. Body slightly rounded; slight notch at anterior margin of oral sucker (figs 1 and 2a), edge enrolled ventrally, mainly in posterior half (fig. 2a). Tegument without spines (fig. 2a, b). Ventral surface of body with numerous dome-shaped protuberances forming glandular papillae with transversal wrinkles (more than 70), arranged roughly in concentric rows around the acetabular region, varying in size from large at the middle of the body to small at the edge (fig. 2a, c). Oral sucker subglobular, subterminal ventral (fig. 2a). Ventral sucker globular in about middle of body. Prepharynx not observed, pharynx muscular, subspherical, slightly longer than wide. Oesophagus slightly longer than pharynx. Intestinal bifurcation in first fourth portion of body. Caeca arc shaped around gonads, terminate blindly close to median line in third fourth of body (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Drawing of Dermadena pseudobalistesi n. sp. obtained using light microscopy. Ventral view showing papillae and organs. Abbreviations: os, oral sucker; ph, pharynx; isv, internal seminal vesicle; esv, external seminal vesicle; te, testis; ep, excretory pore; c, cirrus; gp, genital pore; mt, metraterm; vs, ventral sucker; sr, seminal receptacle; ov, ovary; u, uterus; ce; caeca; gl, ventral gland.

Fig. 2. Micrographs of Dermadena pseudobalistesi n. sp. obtained using scanning electron microscopy. (a) Ventral view showing edge enrolled ventrally, oral sucker, acetabulum, papillae, and cirrus. (b) Dorsal view showing tegument without spines and detail of excretory pore (arrow). (c) Ventral view showing detail of acetabulum and glandular papillae with transversal wrinkles. (d) Ventral view detail of cirrus showing distally widest portion armed with small tubercles (arrow).

Table 1. Morphometric characteristics (average values and range), fish hosts and geographical distribution of Dermadena species.

Abbreviations: PTR, post-testicular region; POR, post-ovarian region. L-left; R-right, measurements in μm (–) not informed.

Two testes, symmetrical with slightly irregular margins, intercecal, posterior to ventral sucker. Cirrus sac elongated, claviform, reaches to level of ventral sucker. Internal seminal vesicle proximal, subglobular. External seminal vesicle developed, curved. Pars prostatic bipartite, proximal part subglobular, distal part elongate (fig. 1). Cirrus long, muscular, distally widest, armed with small tubercles (figs 1 and 2d). Genital atrium distinct. Genital pore opening at level of intestinal bifurcation, anterior to left margin of ventral sucker (fig. 2a).

Ovary posterior to ventral sucker, inter-testicular, rounded. Seminal receptaculum small, claviform, between ventral sucker and left testis. Laurer's canal not observed. Uterus convoluted postero-dorsally to ovary. Metraterm developed, slightly subglobular posteriorly, delimited by sphincter; extending along left side of cirrus sac, anterior to ventral sucker, not reaching margin. Vitellarium follicular supra caecal beginning at level of oesophagus not reaching the posterior margin. Eggs operculated. Excretory pore dorsal, median, between caecal termination (fig. 2b).

Taxonomic summary

Type host: Pseudobalistes naufragium (Jordan & Starks, 1895) (Tetraodontiformes: Balistidae).

Type locality: Puerto Pizarro (03°30′S; 80°24′W), Peru.

Site of infection: Intestine.

Intensity: 13 in one host specimen.

Type specimens: Holotype (CHIOC No. 39736a); paratypes (four specimens CHIOC No. 39736b-e; two specimens MUSM No. 4860).

This article was registered in the Official Register of Zoological Nomenclature (ZooBank) as: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:24488A6D-42C3-4EF1-8ED4-AED6F7DB8EF3

Etymology: The specific name refers to the genus of the fish host.

Taxonomic key

1a Ovary trilobed, vitelline follicles reach close to body margins Dermadena lactophrysi

1b. Ovary not lobulated, wide gap between vitelline fields and body-margins2

2a. Genital pore anterior or level with oesophagus3

2b. Genital pore posterior to oesophagus. Egg length 58–76D. stirlingi

3a. Genital pore anterior to oesophagus. Egg length 82–99 D. spatiosa

3b. Genital pore at level of oesophagus. Egg length 46–61D. pseudobalistesi n. sp.

Molecular and phylogenetic analyses

The ITS2 region gene matrix had 28 taxa and 490 characters, of which 308 were constant and 150 were parsimony-informative variables. The Bayesian analyses returned a mean estimated marginal likelihood of −3083.4375, with a median value of −3083.107. Effective sample size for all parameters were above 100 effectively independent samples and much larger for most parameters, demonstrating the robustness of the samples.

Tree topologies produced with different optimality criteria (ML and BI) were similar, with little variation in node support values (fig. 3). Dermadena pseudobalistesi n. sp. formed a clade with lepocreadiids Neomultitestis aspidogastriformis and Multitestis magnacetabulum with high bootstrap value for ML (95%) and low support posterior probability value for BI (0.64). This clade formed a sister clade with Lepotrema spp., Austroholorchis sprenti and Mobahincia teirae well supported (M = 96%; BBP = 0.76) (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Phylogenetic relationships within the family Lepocreadiidae based on analyses of the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2 rDNA) dataset. The tree was inferred by using the maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods. The nodal support is described at the left by bootstrap replicates and at the right by posterior probability to each node represented. * incongruence between ML and BI. The scale bar represents the number of substitutions per site.

Discussion

Species of Dermadena are included in a small group of lepocreadiids characterized by oval, rounded, or flattened body shape and dorsal surface with excretory pore opening not reaching the posterior extremity (Bray & Cribb, Reference Bray and Cribb1996). The new species proposed belongs to the genus Dermadena due to the presence of scattered glandular papillae on the ventral surface (Bray, Reference Bray, Jones, RA and DI2005). Dermadena pseudobalistesi n. sp. most closely resembles D. spatiosa but can be distinguished by having notches at the anterior margin circumventing the oral sucker and presence of genital pore located at the oesophagus level. Additionally, the new species can be distinguished from D. spatiosa and D. stirlingi by having body that is longer than wide. Also, D. pseudobalistesi n. sp. can be differentiated from D. stirlingi by presenting a well- developed and curved external seminal vesicle. The new species can be separated from D. stirlingi and D. lactophrysi by having a well-developed cirrus-sac and metraterm. Moreover, D. pseudobalistesi n. sp. presents ovary not lobulated and a wide gap between vitelline fields and body margins, which differs from D. lactophrysi.

In addition, the present report provides detailed morphological information on D. pseudobalistesi n. sp. by SEM, showing the organization and characteristics of the tegument surface of the glandular papillae, with transversal wrinkles; distal extremity of cirrus slightly dilated with small tubercle projections; and excretory pore opening situated dorsally.

Manter (Reference Manter1945) described the presence of elevated ventral glandular papillae opening in conspicuous pores varying in shape and distribution in D. lactophrysi by light microscopy. SEM analysis of D. pseudobalistesi n. sp. revealed numerous dome-shaped protuberances forming glandular papillae with transversal wrinkles arranged roughly in curved concentric rows around the acetabular region, varying in size from large at the middle of the body to small at the margin. Moreover, he described that the tip of these protrusions is narrow, and the entire elevated region is nipple-shaped. Thus, SEM should be applied to observe other species of Dermadena to elucidate the importance of this morphological characteristic.

The superfamily Lepocreadioidea was previously reported as grouping 12 families (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Bray and Gibson2005). Nevertheless, Bray et al. (Reference Bray, Waeschenbach, Cribb, Weedal, Dyal and Littlewood2009), through molecular and phylogenetic studies, observed that Lepocreadioidea forms five clades in a polytomy and concluded that these groups have wide morphological diversity. Bray & Cribb (Reference Bray and Cribb2012) reorganized this superfamily based on molecular phylogeny and proposed three lepocreadioid subfamilies. Currently, six families are recognized in the superfamily Lepocreadioidea: Lepocreadiidae Odhner, 1905; Aephnidiogenidae Yamaguti, 1934; Lepidapedidae Yamaguti, 1958; Enenteridae Yamaguti, 1958; Gorgocephalidae Manter, 1966; and Gyliauchenidae Fukui, 1929. According to Bray & Cribb (Reference Bray and Cribb2012), Dermadena is one of the morphologically-typed members belonging to the family Lepocreadiidae due to the typical Opechona-type terminal genitalia.

In the obtained molecular phylogeny, the new species belongs to the family Lepocreadiidae. Nevertheless, due to the use of the ITS2 region alone, discrimination of taxa at the species level is not possible. Sequences of Lepocreadiidae present variable hard-to-align regions without generating possible homoplasy, explaining low values of BPP in some clades. Thus, further studies focusing molecular data on other taxa from the ITS2 region will be necessary to provide more conclusive inferences on the relationships among the lineages of this family. Analysis of the other regions, such as 28S, rDNA, are important to elucidate phylogenetic relationships at the species level. Unfortunately, in the present study it was not possible to obtain sequences from the 28S region.

Species of Dermadena have a wide geographical distribution (Bray & Cribb, Reference Bray and Cribb1996), with D. lactophrysi having been reported in the Atlantic Ocean, D. stirlingi in the Indian Ocean and D. spatiosa and D. pseudobalistesi n. sp. in the Pacific Ocean. The new species is the first described infecting fish species of the family Balistidae and in the South American part of the Pacific Ocean.

Financial support

Jhon D. Chero and Celso L. Cruces were supported by student fellowships from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal do Ensino Superior, Brazil (CAPES) (Finance Code 001). José L. Luque was supported by a research grant from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Brazil (CNPq).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors declare that all applicable international, national and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.