We propose a model of population behavior in the aftermath of disasters. We base this model on the existing literature and on a systematic study of a sample of disasters that have occurred since 1950. Our goal is to inform our understanding of population behavior after disasters, starting from disaster onset through the response and recovery process. Our model explicitly suggests that population behavior progresses through defined stages in the aftermath of disasters. This introduces the opportunity for population-level intervention in the aftermath of such events that can improve population health.

DEFINING DISASTER

A range of definitions has been offered by international governing bodies and by scholars and practitioners. One of the more commonly cited definitions of disaster adopted by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) from the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) considers an event a disaster if it meets 1 of 4 criteria: (i) 10 or more persons dead, (ii) 100 or more persons affected, (iii) declaration of a state of emergency, or (iv) call for international assistance. 1 , 2 Implicit in this definition is the notion that events that do not meet at least one of these criteria are hazards but are not disasters.Reference Carr 3

For the study of the behavioral health consequences of disasters we find it productive to think of the interaction of the hazard (eg, an oil spill) with the natural, physical, environmental, ecological, or social elements of the affected region as generating disasters. In this vein, a hazard will become a disaster only in the context of the vulnerabilities of a particular society.Reference Bankoff, Hilhorst and Frerks 4 Hence, the mere presence of a hazard may make for a disaster in one context but not in another. Additionally, how a population collectively responds to the hazard will help to shape the short- and long-term consequences of the disaster.

CONTEXTUAL AND BEHAVIORAL CAUSES OF DISASTERS

The health of populations after disasters is directly affected by 2 different yet related processes: (i) the contextual determinants (vulnerabilities and capacities) that interact with the hazard and (ii) how a population responds in the face of a hazard. Understanding the contextual determinants of disasters and how hazards become disasters can be invaluable in guiding disaster preparedness efforts.Reference Wisner, Gaillard and Kelman 5 , Reference Rudenstine and Galea 6 For example, knowing which underlying contextual characteristics are vulnerabilities will allow disaster preparedness agencies to assign resources and response programs accordingly. An in-depth discussion of how the underlying context contributes to the formation of a disaster has previously been published.Reference Rudenstine and Galea 6 This article will focus exclusively on how population behavior intersects with the occurrence of hazards to produce disasters. We define population behavior in the postdisaster context as social processes that emerge spontaneously in the context of an impending or threatening hazard. Additionally, our model demonstrates how a disaster, a “focusing event,” can result in new behavior norms within the affected population as well as trigger governing agendas.Reference Bankoff 7 Identifying patterns of population behavior in response to a hazard is essential in thinking about potential disaster response and the long-term effect of disasters on the affected population.

Population behavior after disasters has sometimes been portrayed in the popular media as chaotic and panicked.Reference Tierney, Bevc and KuliGowski 8 , Reference Rodriguez, Trainor and Quarentelli 9 However, systematic analyses of how groups collectively behave after disasters illustrate the emergence of prosocial, predictable, and altruistic behaviors.Reference Tierney, Bevc and KuliGowski 8 - Reference Turner and Killian 11 Despite this body of work, we are not aware of formal efforts to describe patterns of population behavior after a disaster. Understanding the progression of population behavior during a disaster can improve the efficiency and appropriateness of institutional efforts aimed at population preservation after large-scale traumatic events.

POPULATION BEHAVIOR DURING AND AFTER A DISASTER

Our model is based on 2 fundamental assumptions: population behavior is predictable and population behavior will progress sequentially through 5 stages from the moment the hazard begins until renormalization is complete. A limitation of group models is that there will always be individuals whose behavior is discordant with the patterns of behavior of the group. For example, data suggest that media reports and anecdotal observationsReference Wisner, Gaillard and Kelman 5 in the postdisaster context are often “oversimplified and distorted characterizations of the human response.”Reference Tierney, Bevc and KuliGowski 8 (p73), Reference Rodriguez, Trainor and Quarentelli 9 - Reference Turner and Killian 11 Furthermore models that predict collective behavior in different contexts are well established, whereas there is less precedence for predicting individual behavior.Reference Miller 12 Although we appreciate the potential variability in individual behavior, we contend that a model of population behavior after disasters can inform policy and practice in emergency settings.Reference Bangrow, Wang and Barabasi 13 An illustration is the difference in how resources or emergency response personnel are allocated in the postdisaster context depending on whether population behavior is expected to be altruisticReference Tierney, Bevc and KuliGowski 8 - Reference Turner and Killian 11 or antisocial. Without the fear of widespread antisocial behaviors, human resources (eg, police) can be prescribed to emergency response rather than to traditional law enforcement.Reference Tierney, Bevc and KuliGowski 8

Our proposed framework draws on theory from multiple disciplines, including rational choice theory,Reference Smelser 14 , Reference Smith, Rasinski and Toce 15 organizational theory,Reference Kreps and Bosworth 16 - Reference Dynes 18 role theory,Reference Kreps and Bosworth 16 , Reference Dynes 18 , Reference Khan, Wolfe and Quinn 19 and collective behavior theory.Reference Turner and Killian 11 , Reference Aguirre, Wenger and Vigo 20 These theories provide a framework for considering the role of individual versus collective agency on behavior. Moreover, whereas the model of population behavior is grounded in these theoretical frameworks, it emerged through the qualitative analysis of an empirical dataset of disasters that occurred throughout the world over the past half century.

AN EMPIRICAL DATASET OF DISASTERS

We compiled a database of 339 disasters including different types of disasters throughout the world spanning from 1950 to 2005. We used a comprehensive list of disasters that met at least 1 of the 4 criteria for disaster as defined by CRED and the IFRC (outlined above). We included 3 primary categories of disasters: natural, technological, and human-made. Both natural and technological disasters were sampled from comprehensive lists of disasters globally compiled by CRED. In an effort to create an exhaustive list of terrorist (broadly defined) attacks, we compiled comprehensive lists of terrorist attacks compiled by the Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism (MIPT). 21 MIPT’s lists integrate information from the RAND terrorism chronology and the RAND-MIPT Terrorism Incident Database, the Terrorism Indictment Database, and the DFI International’s Research on Terrorist Organizations. Additionally, we compiled several databases of human-made events that do not fall within the terrorist category, such as wars and ethnic conflict, to create the final list of disasters for the human-made category. 22 , 23

Using these comprehensive lists of disasters, we randomly selected a subset of disasters for each disaster category (natural, technological, and human-made) for each of 2 strata: time and geographic region. We stratified disasters into 3 time periods (1950-1970, 1971-1990, and 1991-2005) and 8 geographic regions (North America, South and Central America, Caribbean, Africa, Western Europe, Asia, Eastern Europe and Russia, and Oceania). Consequently, we generated 72 unique combinations of disaster type, time period, and place. Five disasters were selected randomly for each of these 72 combinations to create a 360-disaster dataset. Because there were fewer than 5 disasters in some cells, our dataset consisted of 339 disasters (Table 1). (The dataset bibliography is available upon request.)

TABLE 1 Distribution of Disasters by Disaster Type, Time Period, and PlaceFootnote a

a Adapted from Rudenstine and Galea. Causes and Behavioral Consequences of Disasters: Models Informed by the Global Experience 1950-2005. New York: Springer Publishers; 2011.Reference Rudenstine and Galea 6

b Natural disasters are adverse events due to natural processes of the Earth. They include earthquakes, hurricanes, typhoons, floods, droughts, and tsunamis.

c Technological disasters are due to the failure of modern systems and/or equipment that causes harm to people and/or the environment. They include industrial and transport accidents.

d Human-made disasters are due to human intent such as terrorist bombings, war, and ethnic conflict.

For each disaster we collected a range of information including the type, magnitude, and duration of the instigating hazard. We examined the local and international response to the disasters via records of economic and material assistance as well as government and NGO actions. We reviewed government and academic reports and research studies to assess the short- and long-term outcomes. We also used qualitative sources (media reports and interviews available in public record) to capture the individual, local, national, and international responses to the disaster and recovery period. The above disaster-related information was analyzed in the context of information gathered on the regional and local context from where the disaster occurred. Data were imported into NVivo (QSR International, Burlington, MA) and coded to identify categories of population behavior. The identified categories were developed into larger themes until 5 distinct stages of population behavior after disasters emerged. More details on the sample and on the methods used are given in a monograph on the topic.Reference Rudenstine and Galea 6

A MODEL OF POPULATION BEHAVIOR AFTER DISASTERS

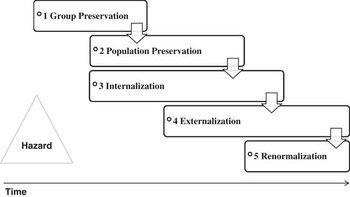

We suggest that there are 5 progressive and overlapping stages of postdisaster population behavior: stage 1, group preservation; stage 2, population preservation; stage 3, internalization; stage 4, externalization; and stage 5, renormalization (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 Model of population behavior after disasters Adapted from Rudenstine and Galea. Causes and Behavioral Consequences of Disasters: Models Informed by the Global Experience 1950-2005. New York: Springer Publishers; 2011.Reference Rudenstine and Galea 6

We briefly describe each stage and provide qualitative anecdotes from our dataset of 339 disasters to illustrate the core components of each of these stages. For a detailed demonstration of how this model unfolds in relation to one specific disaster, see our monograph.Reference Rudenstine and Galea 6

Stage 1: Group Preservation

Group preservation is the first stage of population behavior following a hazard. The individuals immediately and directly affected by the hazard, the compact group, act to preserve life and secure safety. We found that the group preservation phase has 2 identifiable substages: (i) information-seeking and (ii) group preservation actions.

Group preservation does not occur at the expense of emotional reactions to the hazard. In fact, emotional responses, including fear and anxiety, are reasonable and expected responses to events that may pose life-threatening risks. Moreover, such emotional responses lead individuals and groups affected by the hazard to seek out information about their predicament, and the obtained knowledge in turn helps the compact group act rationally to alleviate the threat.

Information-seeking occurs in a number of ways. Speaking with one’s preestablished networks is a form of informal information-seeking. On the other hand, gathering information from authoritative sources, such as the government, media, or employers, characterizes formal information-seeking. Regardless of the type, information-seeking is an essential rational behavior in the immediate aftermath of a hazard because obtaining and evaluating information enhances the ability of the compact group to make rational decisions.Reference Turner and Killian 11 For example, in 1952 an alarm bell notified the miners of a Nova Scotia mine of an explosion. In response to the alarm, 7 miners evacuated the mine prior to the fire spreading while another group of miners closer to the explosion remained in the mine to confine the explosion to a limited area and to help protect other members of the compact group. 24 , 25

After the compact group experiences the initial emotional responses and obtains the necessary information for decision making, it takes measures towards group preservation. Group preservation actions may target the source of the hazard (eg, putting out a fire) or may involve distancing oneself or others from the source of the hazard (eg, evacuating). Evacuation and flight are the most common forms of preservation actions. During a 1970 Mufilira mine disaster in Zambia, 89 individuals were working in the mine’s lower shafts. As mud and water flowed into the mine, the individuals working in the higher shafts observed the growing hazard and “scrambled to the cages to get to the surface” after acknowledging that rescuing those further underground was impossible.Reference Billany 26

The substages of group preservation are interconnected and may serve to preserve the lives of individuals or the safety of the compact group. For example, in 1953 when a railway car crashed in New Zealand, a part of the train was at risk of falling into the river below. However, the train’s guard, spearheading the information exchange process, walked through the train warning passengers to move towards the rear of the train. The guard and a passenger subsequently assisted all but one passenger to evacuate the train. Simultaneously, the passengers located in the train cars that fell into the river after the crash formed “a human chain [to make] their way to the bank.” 27 As seen in this event, the exchange of information affected what actions were taken to preserve the population most immediately affected by the hazard.

Stage 2: Population Preservation

Disasters rapidly affect the broader population beyond the compact group. Stage 2 of our model addresses how the population at large responds as it learns of and is affected by the hazard. During this stage, the population engages in information-seeking and acts to preserve the population. Information-seeking precedes efforts to mitigate the harm to those still in immediate danger. In this vein, obtaining current information helps leaders determine what disaster response is needed and establishes new norms for population perseveration behaviors.Reference Bosworth and Kreps 28 Additionally, the communication of a hazard’s presence, especially to those at risk of experiencing its effect, promotes the safety of the population. A forest fire in 1985 on Korcula Island, off the coast of Croatia, illustrates how population preservation actions can extinguish the threatening hazard and reduce the disaster’s cost to human life. For 4 days, 2000 firemen, soldiers of the civil defense, local residents, and tourists worked together to extinguish the fast-spreading fire while the inhabited areas were evacuated. The fires caused significant property damage; however, the coordinated efforts to fight the fire as well as to evacuate the areas at risk are credited for the absence of fatalities due to these fires. 29 , 30 As shown in this example, population preservation consists of both altruistic behaviors performed by formal response agencies and by volunteers to assist the compact group as well as actions to maintain the safety of those not directly affected by the disaster.

Population preservation behaviors are not limited to those actions that occur in the physical proximity of the hazard. The donation of material assistance, including materials and skills, also provides relief to those individual’s affected and thus is considered both a population preserving and an altruistic behavior.

Stage 3: Internalization

Members of the compact group and those in the general population will have immediate emotional reactions to a hazard and ensuing disaster. Unlike these immediate reactions to a hazard (discussed in stage 1), stage 3 begins after the immediate danger from the hazard has passed and consists of individuals and a population as a whole internalizing the disaster. This includes mourning the loss of persons, property, and a sense of safety; the creation of narratives to help understand what transpired; establishing transitional and long-term memorials that honor the individuals killed and affected by the disaster; a change in routine behaviors that in the postdisaster context feel inappropriate; and the evaluation of attributes of the environment (physical, political, social, and environmental) that may have affected their experience.Reference Rudenstine and Galea 6 , Reference Edelstein 31 - Reference Erickson 34 Many of these forms of internalization, such as the creation of narratives, begin during this stage, but continue throughout stages 4 and 5. In this vein, this stage is a bridge between the individual and group life-preserving actions and acute emotional reactions in stages 1 and 2 and the subsequent behaviors, individual and population level, that constitute stages 4 and 5.

There are 4 substages to the internalization stage: (i) experience emotional response, (ii) seek redress, (iii) change normal activities, and (iv) assess vulnerabilities and capacities. The emotional responses characterized by this stage are qualitatively different from the emotional reactions during stages 1 and 2 in that they may contribute to the formulation of an explanation for what has occurred. For example, following Cyclone Gavin in Fiji in March 1997, a number of residents of less affected areas expressed that their belief in and prayers to God were the reason God spared them from greater damage and loss. 35 Similarly, religion may help individuals and their community overcome the grief surrounding a disaster. Religion helped many in a community of devout Christians find a purpose for the death of 18 girls in a dormitory fire in Vaitupu in Tuvalu, which in turn soothed them in their loss.Reference Taylor 36 Memorials also provide a physical structure through which communities affected by a disaster can honor and remember what transpired. Following a school shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado, United States, informal and formal memorials were established and served as a way for individuals to “connect in visceral ways” to the disaster.Reference Neibuhr and Wilgoren 37 Other communities struggle to accept a disaster or their own vulnerability. Reverend Father George Markotsis reflected that the Cape York, Australia, community “grieved the ‘sense of security’ the tragedy had ripped from the tight community” following a plane crash in 2005. 38

The underlying cause of the hazard, in addition to the hazard’s consequences, will not only affect one’s emotional response but may contribute to individual’s assigning blame. The experience of grief for what is lost will be present irrespective of the type of hazard. However, events of malicious intent (eg, terrorist attacks) or blatant institutional failure (eg, gas leak controllable by the company) may incite a different set of emotional responses including anger and fear than, for example, a natural disaster. Moreover, the combination of anger and fear and an identifiable responsible party may result in communities seeking redress.

During the internalization stage, individuals and the population at large recognize a new set of norms of behaviors that are informed by the recent hazard and its consequences. As a result, in the acceptance of vulnerability, affected communities may alter normal activities or may institute precautionary actions to reduce the chance of future risk. Following a train disaster in Norway on January 4, 2000, Ms Prebble developed a fear of trains. In describing her first train ride following the crash, Ms Prebble stated, “you are conscious of where are you are sitting and how easily you can get out.” As seen through Ms Prebble’s heightened awareness of her vulnerability, she developed subtle shifts in her approach to riding the train.Reference Rice 39

The experience of a hazard brings to the forefront of public consciousness elements of our environment (physical, social, political, and environmental) that increase either our vulnerability or our resilience to the hazard. Discussions take place at the local and national levels about why the hazard and ensuing damage occurred. Embedded within these discussions and formal evaluations of the hazard and postdisaster response is a search for cause or explanation for “what went wrong.” For example, intense debate arose about the close relationship between inspectors from the US Mine Safety and Health Administration and officials at the Jim Walter Corporation following a 2001 explosion at the Brookwood mine in Alabama. Mike Boyd, a union member who worked in Mine No. 5 and whose brother died in the explosion publically “[criticized] the company” citing “fraternization” resulting in “inspectors being more lenient on violations.”Reference Reeves 40 After accusations by many of lax safety assessments and poor enforcement of citations, which ultimately put miners at risk, members of the United Mine Workers of America launched an investigation of the federal agency’s relationship with the Jim Walter Corporation.Reference Pratt and Ellis 41

Stage 4: Externalizing

The externalizing stage is a period in which the emotions and vulnerabilities identified during the internalizing process are actively addressed. There are 2 substages: (i) seeking redress and (ii) addressing vulnerabilities and building capacities. As discussed within stage 3, the type of hazard and the extent of its consequences may affect who is held responsible for the disaster. Formal investigations and criminal or civil charges are 2 ways a population may seek formal redress as well as hold accountable individuals or companies responsible for the hazards itself or its consequences. On the other hand, when structural features are noted as key vulnerabilities responsible for the disaster, blame may be attributed to the individuals responsible for overseeing and minimizing vulnerability, such as electricians following an electrical fire. When the Opuha Dam collapsed in New Zealand in 1997, the Canterbury Regional Council, a political council for the Canterbury region, sought legal action against the company responsible for monitoring the dam.Reference Hunt 42 Furthermore, investigations conducted by the Civil Defense into the structural and managerial failures of the Opuha Dam prior to its collapse resulted in the commission of the Opuha Dam Project in 1998-1999. 43 In other contexts, blame may be assigned to overseeing agencies responsible for managing infectious disease outbreaks.

Despite a common wish to hold someone or something accountable for a disaster, identifying a single cause of a disaster is seldom achieved and culpability may be evaluated differently in disasters that span large areas with varying degrees of damage. The externalizing process following the 2004 floods in Nigeria captures how differing attributions led to different actions within stage 4. Senator Musiliu Obanikoro from Lagos Central held officials from the Land and Urban Planning Ministry accountable for permitting the construction of the Lagos Business School on a drainage channel; this was one of many construction projects approved around vital sources of drainage throughout the flooded areas. 44 Mr. Tunji Bello, Commissioner for Environment, argued unsanitary habits and the “[nonchalant] attitude of Lagosians to their environment” were responsible for the flooding, which resulted from “blocked drains and indiscriminate dumping of refuse into canals and drainage channels.” 45 Lagos’ State Governor Bola Ahmed Tinubu called attention to a number of variables that he believed significantly enabled the flooding, one of which was the packaging of pure water sachets, which consistently blocked drains on the streets. 46

In addition to holding accountable those responsible for the hazard and its consequences, addressing the underlying vulnerabilities that made the population vulnerable to the effects of the hazard is critical to the externalizing process. This is done through enhancing the population’s capacities and through externally led coalition building. Disaster prevention and mitigation efforts may be limited to available resources and political will. For this reason, identifying vulnerabilities is distinct from addressing them. In the flood in Nigeria mentioned above, governing officials worked hard to reduce the flooding and address the growing needs of the population. Only after the threat of the flood subsided did attention shift to reflect on the impact of the flooding on the community. Senator Musiliu Obani-Koro stated at a news conference in Lagos, “What happened last week calls for sober reflection…Every Nigerian must be concerned about this problem [chronic flooding] and all hands must be on deck to tackle it once and for all.”Reference Hunt 42 Moreover, aside from addressing immediate concerns, Governor Chimaroke Nnamani of Enugu State emphasized the need to implement preventative measures. 47 Of note, Governor Tinubu announced and implemented a plan that all “construction in the pathway of canals would be demolished.” 48 In addition, Commissioner Bello and Commissioner Hakeem Gbajabiamila, of Physical Planning and Urban Development, revealed plans for the McGregor canal to be dredged as a long-term solution to flooding. 49

Stage 5: Renormalization

Renormalization is the final stage of our postdisaster population behavior model. Through this phase, new behaviors that emerge in the postdisaster context become normal among those affected by these events. Renormalization consists of 3 substages: (i) cultural adaptation to postdisaster circumstances, (ii) normalization of vulnerability, and (iii) domination of new modes of behavior. Following over 100 deaths in factory fires over a 10-year period, the death of at least 12 people in a garment factory fire on August 27, 2000, in Bangladesh resulted in a 3-phase plan to address fires and risk of fatality: training workers on evacuation, providing firefighting equipment to all factories, and building and labeling fire exits. 50

Inevitably, hazards and their subsequent disasters will modify existing social, political, and economic systems.Reference Fritz and Marks 51 Communities must adapt to the postdisaster conditions, the new normal, in order to survive. For example, after years of using the same architectural designs and materials to rebuild communities damaged by earthquakes between 1968 and 1978 in towns near Pradielis, Italy, a senior government official declared, “the second earthquake taught us that we could not rebuild with our hearts…We needed technology.”Reference Fleming 52 Later rebuilding took into account the risk of earthquakes by adapting traditional architectural designs with more earthquake-resistant infrastructure.

In experiencing a disaster, a community is forced to acknowledge and accept its vulnerability. Residents of Ambon, Indonesia, who are familiar with sporadic and unpredictable terrorist attacks “were back to their daily activities as if the tragedy had never taken place” within 1 day of the bombing near the Maluku governor’s office. 53 As seen in this anecdote, the chronic expectation of vulnerability influences new dominant modes of behavior.

Finally, the renormalization phase ends when the postdisaster context behaviors become dominant. For example, new emergency procedures and equipment may be adopted by companies or local governments. After the 1975 Moorgate Tube Crash in London, the National Rail introduced the Moorgate Control, which served as protective stopping devices to ensure that trains slow down appropriately so as not to crash into the end of tube tunnels. 54

IMPLICATIONS FOR BEHAVIORAL HEALTH

The potential consequences of disasters are vast. Population behavior during and after a disaster will also influence the consequences of the disaster. Furthermore, the role of population behavior in the postdisaster context in shaping population health extends beyond the present disaster. New population behaviors emerge out of disaster circumstances. Internalizing describes the individual and group wish to hold someone or something accountable, whereas externalizing begins with identifying the hazard itself (eg, the terrorist attack or a hurricane) and then addresses the contextual vulnerabilities that aggravated negative outcomes. In renormalization, the population recognizes and accepts how the underlying vulnerabilities were associated with the consequences of the disaster.

For example, during a New York City subway fire in 1990 the communication system was found to be inadequate in the context of the hazard, resulting in delayed rescue efforts.Reference Beckman, Pers and Davitt 55 Yet, the underlying cause of the fire was an error in the electrical wiring of the subway tracks.Reference Sims 56 Initially, public response to the disaster included blame and anger aimed at those responsible for laying the original electrical wiring of the subway system. However, as details of the disaster were made known, public blame shifted to the Transit Authority for communication failures and poor maintenance of the subway tunnel, both of which enhanced the disaster. 57 Public perception that negligence was a large contributor to the disaster’s formation resulted in corrections to the subway system such as increased subway track maintenance.

In summary, externalizing behaviors, which largely take place in stage 4, essentially modify the underlying regional conditions that will become important in the context of future hazards. Externalizing focuses on the culprits (human and systemic) identified during the internalizing stage and is the process through which perceived vulnerabilities are corrected. Moreover, during the normalizing stage new behaviors, originally enacted in response to the disaster, become the new normal. Thus, externalizing and normalizing together set the stage for the hazards that will subsequently occur.

Our model of population behavior is predicated on the notion that how a population responds to a hazard is predictable and sensible and will progress through the described 5 stages until renormalization is complete. Moreover, our model, emerging from a random selection of disasters that occurred throughout the world and spanning half a century, provides some confidence that the proposed 5 stages extend across geographic and cultural divides. For example, as illustrated in the examples provided throughout this article, members of a compact group work to preserve life (stage 1) and members of all cultures experience a period of internalization, stage 3, during which the emotional reactions to the disaster are experienced. While our model suggests that internalization is a universal stage, we do not suggest that the emotions expressed or the form of expression is homogeneous worldwide or even within a particular affected population. Rather, the culture or cultures of the affected population will determine the manifestation and duration of each stage, and in particular stages 3 through 5.

Understanding population behavior as progressing through these phases has the potential to inform disaster preparedness and response efforts. Hazards are unavoidable. Disasters, however, may be mitigated and many of their consequences prevented. For example, if we know that individuals confronted with a hazard will act sensibly to preserve their own safety as well as the safety as those around them, it is essential that disaster preparedness include training and information so that any individual confronted with a hazard can make safe and effective decisions. In anticipation of a hazard or immediately after it strikes, the distribution of accurate and timely information to populations at risk will likely minimize the consequences of the disaster. The usefulness of a model of population behavior extends beyond a specific hazard. Attention to the vulnerabilities identified during the internalization and externalization phases will greatly inform areas of weakness that, if addressed, will reduce the risk that future hazards will pose such disastrous consequences.

In acknowledging the progression of population behavior after disasters we can make our disaster preparedness and response efforts more efficient and effective. Consequently, government and organizational interventions for disaster response should anticipate the expected emerging behaviors and recognize the shifting needs of a population during the postdisaster context.