On August 31, 1976, over a thousand students walked out of Granada's Escuela Nacional de Comercio (ENAC), a technical secondary school that taught accounting and secretarial skills. Their grievances were many: ineffective teachers, deteriorating equipment, and an authoritarian administration, but they were especially incensed by the director's mishandling of a sexual harassment case. Several young women had accused a popular teacher of kissing them against their will, but the director had refused to act unless the teenagers could provide concrete proof of misconduct. The administration's inaction galvanized students and their families. Young people occupied their campus, barring outsiders from entering and issuing communiques. Others formed a commission with their parents to visit the Ministry of Education. Within days, state representatives had agreed to many of the students’ requests, and they returned to the classroom.Footnote 1

Their strike was the latest episode in a long history of student activism in Nicaragua. Students had been a particularly active population since the early days of the Somoza dictatorship, which began when Anastasio Somoza García took power in a coup in 1936. New generations continued demonstrating throughout the tenures of his two sons. Typically, youth from the university led these protests, which were usually directed at the regime's corruption and repression. High school students had often walked out to support their elders, but for most of the Somoza era, they had rarely been at the forefront of the movement against the dictatorship. That changed during the regime of Anastasio Somoza Debayle, who ascended to the presidency in 1967. Indeed, as the 1970s wore on, protests at secondary schools would become increasingly common and culminated in a massive shutdown of the nation's education system in 1978.

The walkouts at the Escuela Nacional de Comercio in 1976 were part of a wave of strikes at secondary schools that year and kicked off a period of intense student mobilization. In the mid-1970s, the 70,000 young Nicaraguans who attended private colegios, public institutos nacionales (large regional secondary schools), and a range of vocational schools were a privileged minority—only 23 percent of teenagers attended secondary school during this period. Those figures actually marked an improvement; a decade earlier, only 27,000 had been enrolled in secondary schools.Footnote 2 The rapid growth, however, put a strain on the country's already insufficient educational resources, and poor conditions in the schools fueled student activism. In 1976 alone, there were over a dozen student protests, and authorities feared they constituted a plot to destabilize the educational system.

As in most places in Latin America, the number of secondary students vastly outnumbered their peers in the university, yet much of the academic literature on student protest in the region has focused on those obtaining higher education. Historians have uncovered the global consciousness that inspired their protests in the long 1960s and the ways in which states sought to contain their activism.Footnote 3 Others have traced the changing meaning of youth in the 1960s and have shown how young people became associated with both the positive and negative effects of modernization.Footnote 4 When secondary students do appear in this literature, they are often the most militant and aggressive protesters. The few scholars who have studied these younger teenagers have traced their militancy to a flourishing of secondary student organizations and the sheer diversity both within and surrounding their institutions. Vania Markarian and Ariel Rodríguez Kuri, focusing on 1968 specifically, examine how state repression escalated student protests. They argue that teenagers adopted more violent forms of dissent in order to force unresponsive authoritarian governments to negotiate.Footnote 5

Thanks to much of this research, historians have developed a solid understanding of the many ways in which youth contest power, but the ways in which they attempt to build power, especially beyond 1968, have been less clear. As was true elsewhere, Nicaraguan students also became associated with modernization, specifically with the nation's drive toward industrialization, but the state did not match its rhetoric with reality. Inadequately funded public schools floundered in the mid-1970s, and students rose up in response. Their strikes catalyzed the wider organization of their friends and families, and secondary students would become a central pillar in the revolutionary coalition that overthrew the Somoza dictatorship in 1979.Footnote 6 Understanding the politicization of this generation, then, is key to understanding the larger process of the revolution.

Educational activism proved to be a particularly fruitful realm of engagement with a regime that regularly repressed dissidents. The Somoza family had long relied on violence to quash opponents, but the tenure of the youngest son, Anastasio Somoza Debayle (1967–79) was particularly brutal. Under his direction, the Guardia Nacional attacked peaceful demonstrators and striking workers. Threatened by growing support for the Sandinista National Liberation Front, the military initiated a sweeping counter-insurgency campaign in mid-1976 that rapidly decimated the ranks of the guerrillas. The trials of prominent Sandinistas filled urban newspapers, while stories of the military's abuse of peasants abounded in the countryside.Footnote 7 Strikingly, the youth who walked out of their schools in 1976 never referenced that political situation. They focused instead on the quotidian difficulties associated with being a student in 1970s Nicaragua: poor funding, inept teachers, and oppressive administrators. For most, these material demands marked the beginning of their engagement with the state. The strike wave thus inducted a generation of teenagers into political activism, and they would go on to demand more radical reforms and eventually revolution.

Although students focused exclusively on campus problems in 1976, the state viewed their ostensibly apolitical requests as subversive. The students’ abandonment of deference to authority and unwillingness to work through the traditional channels of patronage was especially threatening to the regime. So was the fact that their strikes often spread rapidly to other schools and cities and compelled parents to take action. Between January and September 1976, there were at least eight school occupations and dozens more solidarity strikes. Most of the takeovers occurred at the institutos nacionales, which taught thousands of middle- and working-class teenagers. Analyzing student documents, Ministry of Education records, and newspaper reports, I argue that in the context of a decades-long dictatorship, student demands for more democratic schools opened a relatively safe pathway for cross-generational activism that forced concessions from the Somoza regime. Battles over the quality of education, thus, showcased the power of an organized citizenry and laid the groundwork for the revolutionary mobilizations that were to come.

Corruption, Rebellion, and Education under the Last Somoza

Rising inequality, corruption, and repression marked the regime of the last Somoza. Anastasio Somoza Debayle assumed the presidency in 1967. Under his watch, the economy cycled between expansion and contraction—shifts that resulted in growing unemployment and declining real wages in the 1970s. Untroubled by the dire poverty of most Nicaraguans, Somoza used the powers of his office to enrich himself. After a 1972 earthquake razed portions of Managua, Somoza and his cronies sold the donations that had poured in and engaged in rampant land speculation.Footnote 8 Although his close alliance with the Guardia Nacional ensured his hold on power, 40 years of corruption and violence had weakened the efficacy of the state and contributed to rising levels of discontent.

Historically, patronage networks had bolstered the Somozas’ power while simultaneously undermining the state's ability to provide essential services and enforce basic regulations. Robert Sierakowski has argued that in the northern part of Nicaragua, “the state functioned primarily as a network of privilege that distributed employment and permitted illegal behavior on the part of its local allies.”Footnote 9 The Guardia Nacional was the most obvious beneficiary of this policy. In exchange for their loyalty, the military was allowed to run brothels and gambling houses, which were illegal. Other government functionaries and members of Somoza's National Liberal Party benefited from their alliance with the regime, which conveniently declined to pursue charges when corruption allegations surfaced. On the other end of the spectrum, dissidents had a hard time getting authorities to investigate crimes committed against them. Sierakowski found that even somocistas who complained about corruption within local government were ignored, if not ostracized. Such widespread impunity severely crippled the ability of municipal governments to collect taxes and protect citizens, while other less scrupulous politicians took advantage of the situation to levy random fees and fines.Footnote 10

The regime's corruption boosted the popularity of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), a socialist guerrilla organization that formed in the early 1960s. Frustrated with the Somozas’ dynastic rule and inspired by the Cuban example, the guerrillas sought to foment rebellion in the country's mountainous northern region. When these efforts repeatedly proved unsuccessful, the FSLN began focusing on building mass support in urban areas. By the early 1970s, its work with university students and the urban working class had created a growing network of sympathizers, and the Sandinistas began orchestrating dramatic attacks on the regime. In December 1974, rebels invaded a party celebrating the US ambassador and took the guests hostage. To obtain their release, the humiliated dictatorship was forced to fly more than a dozen political prisoners to Cuba. In response, Somoza intensified his efforts to quash the Sandinistas. He declared a state of siege that lasted until September 1977, suspending constitutional guarantees, muzzling the press, and unleashing the Guardia Nacional. The years 1975 and 1976 were particularly violent; the military detained, tortured, and killed anybody suspected of helping the rebels.Footnote 11

Despite the repression, multiple sectors increasingly mobilized in the 1970s. Catholic liberation theology galvanized workers, students, and other groups, who began organizing in earnest. Workers were particularly active in this period, striking for higher wages and better conditions.Footnote 12 Facing eviction and disillusioned with the Somoza regime's failed reforms, campesinos from various communities joined together to occupy disputed landholdings, hold protests, and eventually ally with the Sandinistas.Footnote 13 In urban areas, neighborhood associations sprang up to contest the regime's inadequacies, including its failure to supply electricity, water, and other basic services.Footnote 14 University and secondary students sometimes helped with these efforts, but in the mid-1970s, they largely focused on the myriad problems facing the nation's schools.

Years of administrative neglect, malfeasance, and poverty had taken its toll on the educational system. Miguel de Castilla Urbina has argued that the system's inadequacy was a product of the country's export orientation. The economy, historically, was based on agriculture, which largely depended on the kinds of physical labor that could be learned on the job. Thus, there was no social or economic push for the state to build schools. In the 1960s, however, the government, urged on by both the successful Cuban Revolution and the US Alliance for Progress, half-heartedly attempted to diversify and industrialize the economy and, to this end, promoted technical education. These new technocrats were to help develop the nation's nascent industry and thus contribute to Nicaragua's modernization.Footnote 15 Bureaucrats began emphasizing the need to turn students into the productive entities the economy required, and Somoza, tasking students with continuing the national development projects he was initiating, promised to spare no expense to educate this new generation.Footnote 16

With millions in foreign loans and the guidance of experts from the US Agency for International Development (AID), the state focused on building more classrooms and expanding enrollments, but these efforts proved inadequate. In terms of raw numbers, they did meet their goals: between 1965 and 1974, the number of students in intermediate education (which includes secondary schools and vocational schools) rose from 27,000 to over 70,000. In the same period, the number of intermediate schools rose from 134 to 264. These were significant increases, yet they did not keep pace with population growth, and thousands of young people, especially those in the countryside, remained without access to any form of schooling. Moreover, these priorities did little to improve already existing classrooms or the dismal retention rates. The emphasis on quantity and not quality meant that schools continued to suffer from chronic understaffing and lack of resources.Footnote 17 Consequently, by 1976, there were more students enrolled in Nicaraguan schools than ever before, but they faced daunting conditions.

Problems within the Ministry of Education only compounded structural difficulties. The educational bureaucracy reflected the state's mismanagement and was dominated by political appointees who took little interest in improving a deeply troubled system.Footnote 18 In spite of their financial limits, ministry bureaucrats had bad habits of overspending, paying “phantom teachers” who failed to show up for work, and missing scholarship payments for months at a time.Footnote 19 Meanwhile, teachers often faced low salaries and irregular paydays.Footnote 20

By 1976, the ministry was plagued by scandals and frustrated Nicaraguans were taking matters into their own hands. Stories abounded in the press of schools without teachers and communities without schools. Families living near Costa Rica or Honduras often sent their kids across the border for school—much to the chagrin of the country's nationalist politicians.Footnote 21 Those in rural areas, which the regime had historically neglected, pooled their already meager resources to construct their own schools. These families organized themselves in hope that the state might then send a teacher, and when that did not happen, they registered their complaints with the ministry and in Novedades, the regime's media organ.

Indeed, the regime's newspaper became a kind of clearinghouse of parental complaints and requests for resources. This was especially true for problems in primary schools—older teens initiated their own claims for redress. Novedades, for example, reported that the community of Valle San Esteben promised to build a school if the ministry would send them the material.Footnote 22 When professors at the Centro Escolar “Julia García, Viuda de Somoza” decided to raise money for cleaning supplies by requiring students to supply groceries, which the adults would then cook and sell back to students, parents complained to the newspaper. Novedades promptly published the story and demanded the ministry punish the enterprising faculty.Footnote 23 Other staff members took to submitting requests for badly needed equipment to the daily. In July 1976, for example, the newspaper reported that administrators at a school in Chontales were asking the government or some private entity to donate two typewriters.Footnote 24 Although these requests reflected poorly on the Somoza regime, Novedades likely published them because they followed a long tradition of patronage politics in which citizens petitioned the state for basic services. Nonetheless, the frequency of such reports suggests that the nation's schools were facing severe shortages of resources and personnel.

Disruption in the upper echelons of the ministry compounded the sense of disorder. In mid-May 1976, the minister of education, Leandro Marín Abaunza, resigned abruptly. The day after his resignation, the state introduced his replacement, Helia María Robles Sobalvarro, a former teacher, textbook author, and curriculum consultant.Footnote 25 Recently returned from her doctoral studies in Italy, Robles faced the daunting task of reforming Nicaragua's schools precisely at a time when students had decided they had had enough.

The problems in the educational system reflected the larger challenges facing the nation. In 1976, Nicaragua was entering its fourth decade of Somoza rule. The political stagnation of the dictatorship had taken its toll on the country—corruption and nepotism permeated the government. The state was failing to deliver basic services to large swaths of the population, which was increasingly organized. Specifically, educational deficiencies brought parents together to make demands on the regime. Considering the wide reach of public education, or lack thereof, many Nicaraguans had firsthand knowledge of the Ministry of Education's inefficacy. Media coverage in both regime and opposition newspapers confirmed the extent of the problem; this diffusion primed society to sympathize when its children rose up in protest.

“The Anomalies are Many:” Educational Authoritarianism

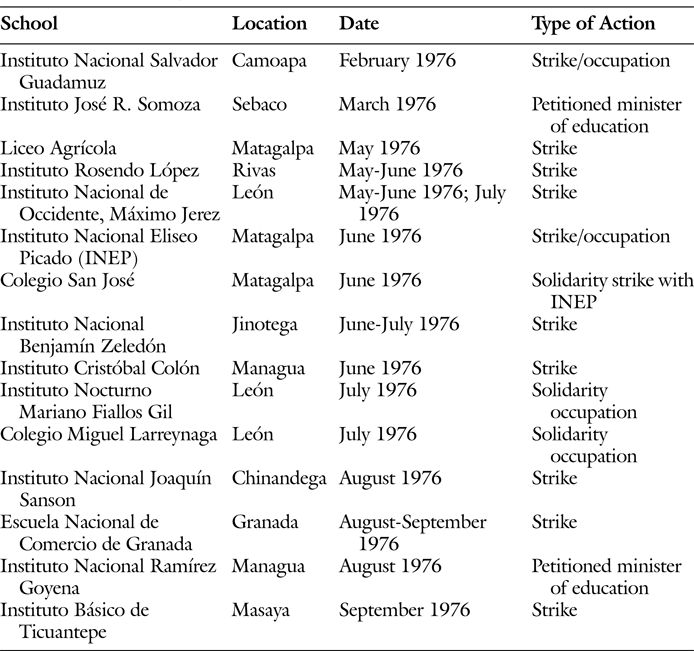

If the educational system had come to reflect the problems of the Somoza regime, schools had become microcosms of the state, and many youths were ready to rebel. Between May and September of 1976, there were at least a dozen strikes and school occupations (see Table 1).

Table 1 Confirmed Actions at Secondary Schools in 1976

Sources: “Termina conflicto en Liceo Agrícola,” La Prensa, May 31, 1976 and others; Archivo General de Nicaragua, Fondo Educación, Files related to Huelgas in Jinotega, León, Matagalpa, Granada, Chinadega, Camoapa in Boxes 349, 358, and 394.

Unlike the parents who made respectful requests in national newspapers, teenage protesters were not content to petition politely for increased resources. Instead, they took over their campuses, refusing to speak to anybody except a (properly credentialed) representative from the Ministry of Education. While they waited for the bureaucrats to show up, teenagers issued lists of demands that essentially called for the complete transformation of their schools. They wanted corrupt teachers and administrators removed, better pay for staff, and their rights as students to organize on campus. Their petitions shine a light on the ways in which their experiences with educational authoritarianism compelled students to get organized.Footnote 26 Their desire for better resources and dignified schooling conditions meant that their complaints reflected a more democratic vision for the nation's schools—and by extension a more expansive notion of democracy—one that went beyond voting and political freedom to encompass the right to quality education.Footnote 27

Secondary students, often with the help of organizers from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua, had been forming their own campus-based groups since at least the 1950s, but there is little record of what they were doing and how active they were, until about the 1970s.Footnote 28 That said, it is clear that the Sandinistas had recognized early on the mobilizing potential of teenagers. When he was at the Universidad Nacional in the 1950s, Carlos Fonseca, who co-founded the FSLN in the early 1960s, had used his position in the student government to encourage secondary students to form their own school-based organizations.Footnote 29 Years later, in the late 1960s, he urged the members of the Revolutionary Student Front (FER) to focus on organizing the numerically superior secondary students, and the radical student organization was active, if somewhat small, on several campuses.Footnote 30

After suffering devastating military defeats in the late 1960s, the FSLN doubled down on these organizing efforts. Committed to building their popular support base, the Sandinistas embraced a strategy called acumulación de fuerzas en silencio (clandestine accumulation of forces). The former Sandinista comandante, Mónica Baltodano, has explained that this tactic “gave the people a more important role: that students did the [kind of work] that goes with being a student, [the strategy meant] harnessing the distinct potential of the people.”Footnote 31 The goal of this kind of grassroots organizing was to build up intermediary organizations while also spotting talented and committed organizers who could be potential collaborators.Footnote 32 To this end, Sandinista university students worked with younger teenagers, traveling around the country to advise youth clubs, give talks, and organize workshops. They promoted the creation of local branches of the Movement of Secondary Students (MES) and the Association of Secondary Students (AES).Footnote 33 Sandinista university students and militants advised many of these student groups, which were clandestinely aligned with the FSLN. The local branches, however, were led by secondary students themselves, many of whom were likely already Sandinista sympathizers if not militants.Footnote 34 That said, the level of repression in this period meant that the student organizations’ connections with the FSLN, while perhaps suspected, would not have been publicized.

In the mid-1970s, these Sandinista-aligned secondary student organizations focused almost exclusively on educational concerns, and this was a deliberate strategy. Although the clandestine accumulation of forces strategy was terminated in 1974, the Sandinistas continued to encourage people to organize within their immediate milieus. In August 1976, Bayardo Arce, a key Sandinista organizer, directed Baltodano, who was then a Sandinista militant organizing in Estelí, to work with student recruits to gather information about conditions in the local schools. Once that has been done, he wrote, “we should begin agitative work. Denunciations on flyers. [Posting] questioning posters. Sowing doubts. Emphasize student motivations, then with the concrete social problems of students we can [move on to] national politics.” Arce and Baltodano thus recognized that educational grievances could be a powerful organizing tool. Arce's instructions continued, “Have each student recruit tell what are the most pressing problems in their schools, in their neighborhoods, in their community. And how we should respond to them.” The goal, then, was to turn students into political activists and eventually into Sandinista militants.Footnote 35

The clear role Sandinista militants played in leading the largest national student organizations and promoting student mobilization should not detract from the agency of the young activists themselves. After all, as Arce told Baltodano, students should identify the problems and they should come up with the solutions. Moreover, it is important to stress that not all students mobilizing during this time were sympathetic to the FSLN.Footnote 36 Regardless of Sandinista involvement, then, the clear uptick in organizing at secondary schools in 1976 provides a window into the ways in which teenagers learned how to be political activists.

They had much to organize around, and their grievances during the 1976 strike wave focused on the way that their schools reflected elements of the state's authoritarianism. Students’ chief complaints at many of the protests that year centered on entrenched school directors who had amassed tremendous levels of control over their campuses. They resented directors for punishing teachers who did not fall into line, and for protecting incompetent staff. At the Instituto Nacional de Camoapa, teens went on strike after their director fired a particularly popular French professor without explanation. Like other administrators, that director had also used his power to employ family members: students and their supporters wrote a letter to the minister of education complaining that he had hired his wife to teach English although she was not qualified.Footnote 37 Teachers closely allied with directors received special privileges and plum course schedules. At the National Institute of Matagalpa, the director, Emilio Sobalvarro (a relative of the new minister of education) protected and awarded his inner circle, many of whom abused their power. A communique that circulated during the student strike in Matagalpa pointedly asked, “Why has he surrounded himself with a small group, alienating the teachers who don't submit to his manner of managing the institute, giving them nothing and the few everything?”Footnote 38

Beyond their effect on the quality of education students received, such practices created the conditions for abuse. Perhaps the most egregious case took place in Granada. There students alleged that the director of the Instituto Nacional de Comercio, Virgilio Morales, knew the social science teacher Adolfo Rosales had sex with a student who became pregnant but had done nothing about it. Rosales was particularly well-connected—his uncle was the head of the School of Education at the Universidad Nacional, and both he and Morales went out of their way to defend Rosales and cover up the persistent allegations of sexual misconduct. When Morales prevented the discussion of the case at a general assembly, students were outraged, writing that he had behaved as if “it was not the duty of the director to constantly investigate the center's progress and take measures to correct it.”Footnote 39 There were other instances of unacceptable behavior. Students in Camoapa alleged that at least two teachers regularly came to class drunk.Footnote 40 At Matagalpa's Instituto Nacional, the deputy director and teacher Julio César Medina outfitted his office door with electrical wires to shock visitors, apparently as a security precaution, but both teachers and staff told La Prensa that they feared Matagalpa's unreliable electrical output could have dangerous consequences.Footnote 41 In many of these cases, the directors had long been aware of the abuses and done nothing. A culture of impunity was, thus, a central aspect of Nicaragua's educational authoritarianism, and it drove students on several campuses to strike.

Such impunity had very real financial consequences for students and their families. Young strikers that year complained of teachers who sought to profit from their positions. Medina, who guarded his office with electrical current, edited his own textbooks, which he required his pupils buy new each year. When students tried to use older copies, he informed them that those “were no longer valid because the new edition has been augmented and corrected.”Footnote 42 Teachers selling their own textbooks was such a widespread problem that the ministry eventually cautioned school directors against the practice.Footnote 43 The sale of school uniforms also proved a profitable arena for teachers and administrators. In Matagalpa, the director of the Instituto Nacional had allowed one of his “favorites” to privatize the school's co-op, where families bought material for uniforms.Footnote 44 While cronyism and corruption ran rampant in the government, students were unwilling to abide it on their campuses, and young protesters demanded the removal of school directors and their sycophants at several protests that year.

Students did not just want dictatorial administrators gone, however; they also insisted on greater democracy in their schools. As a result of widespread corruption, they took a surprising interest in the day-to-day financial administration of their campuses. They condemned the general lack of fiscal transparency and accused many administrators and teachers of financial misconduct. Protesters at secondary schools in Masaya, Granada, Matagalpa, Jinotega, and Chinandega all mentioned financial irregularities in their list of grievances. Often, they charged the directors with financial incompetence, but sometimes they were more specific. In 1976, a student delegation from Chinandega told reporters for La Prensa that in the past year over 1,000 córdobas had disappeared from their school's accounts.Footnote 45 In Jinotega, young protesters demanded a five-year audit of the school's accounts as well as a study of its inventory, in order to understand what had happened to funds raised for the school's improvement.Footnote 46

The students’ demands for financial transparency in the context of a decades-long dictatorship was in and of itself notable. Even Somocista politicians who requested audits of municipal accounts were driven out of office by regime loyalists who did not want the books examined too closely.Footnote 47 In demanding their schools give an honest accounting of their finances, teenagers were calling for a level of government transparency that did not otherwise exist in Nicaragua at the time. Moreover, they were questioning the authority (and competence) of state-appointed directors and claiming for themselves the right to monitor their behavior.

Student interest in the mundane aspects of accounting in their schools stemmed from the fact that their campuses desperately needed the missing money. By the mid-1970s, many institutes had fallen into a state of disrepair—the result of both a devastating 1972 earthquake and the state's inadequate investment in education. On some campuses, teachers apparently dealt with budgetary shortfalls by charging for tests, and students were often tasked with raising funds for school libraries, but even such questionable measures were insufficient.Footnote 48 In 1976, many of the strikers railed against ill-equipped libraries and the gradual disappearance of books. In Camoapa, the library of the Instituto Nacional had only magazines.Footnote 49 Other youngsters lamented the lack of educational materials and outdated or broken equipment. In Granada, for example, when students insisted on the dismissal of the professor who sexually harassed students, they also demanded more typewriters and desks.Footnote 50 These were demands similar to the ones the parents of primary school children and administrators were making in the daily newspapers, but students were not willing to limit their requests to these bare necessities. Instead, secondary students across the country made their petitions in the context of a much wider call for institutional change. In so doing, they recognized that their schools needed more resources because government employees were mismanaging public money—a claim that parents and certainly school employees never made in the media.

Teenagers’ desire for broad institutional change was most clear in their demand for student rights. Dictatorial directors particularly aggrieved them because they denied students a voice. At several strikes in 1976, students explicitly rejected limits on their right to assemble. In Matagalpa, a communique circulated during the strike pointedly asked:

Why has [Emilio Sobalvarro,the director of the Instituto Nacional Eliseo Picado] systematically opposed the organization of students?

Why has he never allowed students to participate in anything that he does?

Why has he alienated parents, refusing to allow them to organize a council that cooperates with the school?Footnote 51

When the Movimiento Estudiantil de Secundaria (MES) took over three schools in León in July, students demanded “there be liberty to form student associations at the schools . . . without the intrusion of the administration.”Footnote 52 A few weeks later, their peers in Granada requested the right to hold assemblies and the right to have their student council draft and enforce their own bylaws.Footnote 53 Students’ insistence on certain democratic practices—including the right to organize and the right to dialogue with authorities, for both themselves and their parents—challenged the hierarchy within their schools and within their society.

Young people wanted to participate in campus decision-making because without their input, directors made decisions that hurt their sense of dignity and their families’ economic well-being. Scholars of student movements have often focused on sartorial conflict as a hallmark of generational rebellion and specifically the counterculture movements of the 1960s and 1970s.Footnote 54 Those kinds of disputes certainly generated tensions in Nicaragua. Youth on at least two campuses in 1976 protested rules that forced male students to cut their hair short.Footnote 55 Just as often, however, conflicts over dress were rooted in the country's deep-seated inequality. In León, teens walked out after the director of the Instituto Nacional Máximo Jerez instituted a school uniform that required blue jeans—an expensive commodity in mid-1970s Nicaragua that many families simply could not afford.Footnote 56 In Masatepec, students were upset when the director of the local school refused to allow youngsters to wear brown shoes, instead of black, to march in the school's Independence Day celebrations—many only owned one pair.Footnote 57 Whether these measures hurt their wallets or their dignity, young people sought to wrest some control from administrators.

The breadth of the students’ petitions was one of the most remarkable aspects of the 1976 strikes and protests. Communique after communique did not make just a single request but rather issued a list of demands that, in total, amounted to a complete overhaul of their campuses. Students sought to turn their schools into participatory democracies, and in so doing they chipped away at a wider culture of authoritarianism that had pervaded their society under the Somozas. In fact, teens were calling for rights that even the general public did not enjoy: the right to assemble, the right to participate, the right to greater administrative transparency, and others. In so doing, young people held up a mirror to the wider society—they were not going to tolerate the kind of oppression and corruption that had long been part of everyday life in Nicaragua.Footnote 58

Broad public support for this agenda suggests the subversive potential of educational activism. An editorial discussing the problems at the Instituto Nacional Joaquín Sanson Escoto in Chinandega wrote that the nation's secondary schools “need to be restructured because it is within the [educational] center that the young students should be treated, not as an elementary school child, but as youth. This way they can understand that they are about to pass through a door, to enjoy the rights of citizens. The schools should practice a democratic philosophy.”

That the author was surely aware that Nicaragua was not, and had not been for some time, a democracy lends his words a subtle irony. He went on to explain that one of the major problems facing the nation's schools was the “dictatorial” directors who have gotten too comfortable in their position: “If a director stays too many years in the same school . . . he believes himself to be lord and owner, he comes to think of himself as a necessary person. Then he surrounds himself with followers he can make or break.”Footnote 59

He could easily have been discussing the Somozas’ long tenure and the family's relationship with its sycophants. Scholars of education have observed that schools tend to mirror the structure of their societies in order to prepare students for their future roles as citizens.Footnote 60 That function means that any criticism of the ways in which schools are structured is an implicit critique of the society they reflect. In her study of Argentine youth in the mid-twentieth century, Valeria Manzano observed that secondary schools in the 1950s enforced authoritarianism, and by extension, student protests constituted a rejection of such practices.Footnote 61 The Nicaraguan editorialist's language suggests a similar phenomenon was occurring there: in protesting educational authoritarianism, students and their supporters indirectly critiqued the state, managing to do so in ways that flew under the radar of the censors.

In the mid-1970s, Nicaraguan public schools were badly managed and falling apart. Part of the problem was budgetary. Limited state support meant directors and teachers lacked resources and passed the charges onto students, but these were public schools and many families could not afford extra charges. As it was, many students had gone without their scholarship payments for months in 1976 because the Ministry of Education had run out of funds to pay them.Footnote 62 Their protests then were about not only institutional mismanagement but also the absence of an effective government bureaucracy. The student strikes thus managed to critique the regime without ever mentioning Somoza himself. In so doing, students envisioned for themselves a different kind of educational system, and by extension a different nation—one that was more transparent, democratic and effective—and they would take great risks to make that vision a reality.

Chronology of a Strike

The strikes of 1976 had a ripple effect throughout their communities. While the protesters waited for a response to their demands, they rallied friends and families to their side. In Matagalpa and León, solidarity strikes virtually paralyzed secondary education. In smaller cities, parents mobilized to support their teenage children. Scholars writing about the African American and Chicano walkouts in the United States in the 1960s have argued that the demonstrations politicized both the students and their communities.Footnote 63 This was true in Nicaragua as well, where the myriad of problems facing secondary schools and the state's response to student protests compelled wider political mobilization. In this way, the student strikes managed to promote democratic action during a period of severe censorship and repression. An in-depth look at just one strike, the June 1976 walkouts at Matagalpa's Instituto Nacional Eliseo Picado (INEP) illustrates how the secondary school strikes brought together youth and adults from across the country in a joint project to demand better schools and by extension challenge the state's authoritarianism.

Matagalpa would become famous for its rebellious youth who took up arms in 1978 against the regime, but in the mid-1970s, only a small group of teenagers was organizing to that end. José González told an interviewer that he and about ten other youth from schools across the city came together in 1974-75 to form their own Association of Secondary Students (AES). Early on, they received advice from a FER activist in Managua, and some members like Marcos Largaespada and González were soon recruited by Sandinista militants. AES leaders studied at the INEP and the private Colegio San José, and these connections would help the strike spread quickly.Footnote 64

Because of the danger of dissent in the 1970s, students implicitly understood the need to organize a critical mass before undertaking any sort of dramatic protest, and in so doing they politicized their campuses. In Matagalpa, the demonstrations at the INEP started when a small group met on the school field on May 20, 1976 to protest an administrative demand that male students have military-style haircuts. After the director called in the Guardia Nacional to break up the gathering, students met to discuss the school's many problems and decided to form a central committee. On June 3, some 500 students agreed to strike and the following day at 11:35 am, 55 young people took over their campus. They promptly set up various committees to ensure that the strike proceeded smoothly. Groups were tasked with standing guard, producing propaganda, providing food, and keeping things clean.Footnote 65 Such discipline not only ensured order but also provided concrete ways for students to participate. Other takeovers were similarly organized and featured large numbers of protesting youth.Footnote 66 In León, 1,400 teenagers at the Instituto Nacional Máximo Jerez went on strike in July 1976 to demand the removal of their director and sub-director, and the following month over a thousand young people at the Escuela Nacional de Comercio in Granada went on strike to protest the administration's mishandling of a sexually predatory teacher.Footnote 67

These were massive protests for Nicaragua, and a high level of organization was necessary to stymie official attempts to delegitimize them. Immediately after the Matagalpa occupation, for example, teachers at the INEP publicly accused the young protesters of “transforming the center into a cave of ‘orgies’ and ‘bacchanals’ where young women and men have gone beyond all moral principles, violating the ‘dignity’ of the center.”Footnote 68 Such exaggerations were quite common during Latin America's Cold War, as authority figures often equated any kind of grassroots empowerment with moral subversion.Footnote 69 Students were ready for the accusations, and they issued a communique reminding their parents that they “know the way in which we have developed our activities, via different committees that work day and night for better student discipline.”Footnote 70 Their efforts thus helped prevent the state from demonizing youth activists.

The 1976 strikes not only politicized the campuses where they took place but affected other schools as well. Indeed, the solidarity of teenagers at neighboring schools was vital for maintaining the strikes. Within an hour of the takeover at Matagalpa's Instituto Nacional, students from across the city had arrived to join the strikers. Surrounding the school, these youngsters prevented the Guardia Nacional from dislodging the protesters the first day.Footnote 71 Within days, all of Matagalpa's secondary schools and some 4,000 young people were striking in solidarity with the students from the Instituto.Footnote 72 By the end of the month, solidarity actions were underway at the institutos nacionales in Jinotega, Jinotepe, and León. Their peers also provided concrete aid. After the military dislodged the protesters from the INEP, students at Matagalpa's elite all-girls school, Colegio San Luis, allowed the strikers to meet on their own campus, much to the chagrin of the school's director.Footnote 73

Such solidarity actions not only put pressure on administrators and bureaucrats, but also effectively publicized school irregularities and provided an example of what could be done about them. In fact, students in both León and Jinotega turned their sympathy strikes into protests for their own grievances. In León, students demanded the removal of several administrators at the Instituto Nacional Máximo Jerez for “irregularities” and in Jinotega, youth at the Instituto Nacional Benjamín Zeledón demanded, among other issues, a financial audit and a thorough inventory of school equipment. They, in turn, earned the support of various local secondary schools.Footnote 74

Perhaps because of this capacity to spread quickly, student protests often drew the attention of the Guardia Nacional. Sometimes the guardia was called in by school administrators who sought to disperse the strikers. At other times, the Ministry of Education requested their intervention. In Matagalpa, two soldiers arrived soon after the occupation of the INEP with a warning that they would remove the students if they “did not abandon the center within four hours.” The protesters refused.Footnote 75 At the request of Ministry of Education bureaucrats, the local Guardia Nacional commander attended the negotiations with students. His participation, given the military's reputation, must surely have been ominous. Indeed, at 3:00 am on the morning of June 7, a Guardia patrol forcibly removed over 300 protesters from the building.Footnote 76 Soldiers were a constant and threatening presence at other strikes that year. In León, the Guardia Nacional interrogated protesters who participated in a school occupation in July, and soldiers in plainclothes patrolled the area surrounding the campus.Footnote 77

The military's intervention galvanized parents, many of whom had been supporting their children since day one. On the first day of the school occupation in Matagalpa, parents had sent their children food, blankets, and other supplies. Some even occupied the school alongside their children and were dislodged with them on June 7.Footnote 78 After soldiers removed the protesters, parents sent angry missives to the Ministry of Education demanding to know who had called in the Guardia and why they had not been consulted.Footnote 79 In the wake of most student protests, parents hastily organized themselves, forming groups to support their children and negotiate on their behalf. In Matagalpa, for example, within a week of the takeover at the Instituto Nacional, a delegation made up of 44 parents and 15 students had traveled to the capital to meet with the minister. Some of the parents in the delegation did not even have children at the National Institute. Their kids attended one of the city's other schools, but the solidarity strikes were affecting them too, and they wanted the problem solved.Footnote 80 Not all parents were sympathetic: those whose children attended the private Colegio Santa Teresita were so concerned about the situation that they wrote to President Somoza, requesting his intervention.Footnote 81 For the most part, though, parents went out of their way to support their children by drafting their own communiques, talking to the press, writing to the Ministry of Education, and participating in the negotiations. Their children's activism had paved the way for their own mobilization.

Yet, just as there were divisions among parents, so too were students divided. Consensus can be hard to build, and the young protesters did not always have the unanimous support of their peers. On the first day of the Matagalpa strike, the presence of several “reactionary young women” nearly resulted in a physical confrontation.Footnote 82 From May through September, the peak months of student protests, La Prensa printed letters to the editors from students, parents, and colleagues offering support to professors and administrators facing criticism. Others wrote directly to the Ministry of Education. In one particularly striking example, over 500 students in Granada signed a letter of support for Professor Adolfo Rosales, who had been accused of sexual misconduct. They extolled his “magnificent [career] trajectory,” suggesting that his accusers had wrongly interpreted his friendly manner and blaming the protests on leftist agitators.Footnote 83 The petitioners had clearly been provoked to take action by their peers’ protest. However, despite the presence of a vocal opposition, the large number of students who walked off their campus and organized strikes suggests a majority were dissatisfied with the status quo and wanted reform.

Despite the myriad and diverse reasons that existed for the protests, the Ministry of Education nonetheless suspected there was a national movement working to create disorder in the nation's schools, a charge which called into question the students’ agency and disregarded their well-documented grievances.Footnote 84 As is often the case when young people take political action, local administrators pinned the blame on outside agitators—students from other cities, disgruntled teachers, and unnamed “outside agents.”Footnote 85 As mentioned earlier, Sandinista militants, many of whom were teenagers themselves, were almost certainly advising or directing some of the protests that occurred in 1976, but to focus on the role of “outside agitators” minimizes the conscious organizing decisions made by students and their supporters. Regardless of the role of the FSLN, teenagers were the ones who made demands, walked out, organized committees, and occupied campuses. Thousands of students who were not affiliated with the guerrillas decided to strike or join solidarity protests that year. Sources from the Ministry of Education reveal that students traveled between schools, alerting their peers about protests and encouraging them to join the demonstrations.Footnote 86 In fact, with or without the assistance of older allies, Nicaraguan teenagers managed to stage impressive protests and coordinate actions across several cities.

The 1976 strikes show that educational issues constituted a potent vehicle for mobilizing wider society. It was precisely the nature of the students’ protests, the demand for democratic schools, and the youthful identity of the protesters, that spurred wider support and made their activism so threatening to the regime. Whether they disagreed with the protesters or not, large numbers of ordinary Nicaraguans were engaging with the state, thinking about the quality of their schools and the nature of their organization. Thanks to their strikes and protests, education thus became an accessible arena for organized political struggle, and the state would be forced to respond.

The Ministry's Response to the Strikes

Remarkably, the secondary school strikes of 1976 were fairly successful. Whereas in other parts of Latin America, contemporaneous conflicts over bread-and-butter student issues had led to violence, in Nicaragua, the state displayed a surprising willingness to negotiate with the young protesters.Footnote 87 While teachers and administrators did call the military to remove students occupying campuses, the violence did not escalate in 1976. The relatively peaceful resolution of the strikes was testament to the power of the cross-class and cross-generational movement students were building. The student strikes, the parents’ visits to the Ministry of Education, and the media attention publicly called into question the state's legitimacy, and bureaucrats were forced to negotiate. To stabilize the regime, they offered some concessions while quietly instituting new rules that sought to quell future dissent.Footnote 88 The ministry's response thus highlights both the nascent power teenagers were building and the limitations of a campus-based movement.

School occupations were so disconcerting that the regime immediately sent representatives to investigate. For example, the Ministry of Education dispatched two delegates to Matagalpa the very day students took over the Instituto Nacional Eliseo Picado.Footnote 89 In Granada, two investigators from the Ministry of Education were already on the job and making inquiries the day after students declared their strike at the Instituto Nacional de Comercio.Footnote 90 Such haste was remarkable for a state that generally ignored allegations of corruption, and it underscores the power of student strikes.Footnote 91 In León, for example, it took just one fifth-year student interrupting a class at the Instituto Nacional Máximo Jerez to cause so much disruption that the school day ended early. When administrators decided to deny strike leaders entrance to the school, the senior grades rebelled and refused to come to the first hour of classes.Footnote 92 These rapid mobilizations suggest that discontent was rampant, and schools were essential ticking time bombs.

Consequently, bureaucrats took their investigation seriously. Once on site, Ministry of Education officials typically interviewed staff, faculty, students, and sometimes their parents. They also observed classes and inspected facilities. Sometimes these investigations were cursory; in Matagalpa, for example, investigators initially came to the conclusion that the student complaints had no merit, but, considering that the director was eventually removed, further investigation must have changed their minds.Footnote 93 Others were more critical of the schools, even if still biased against the students. The investigators in León, for example, noted the lack of educational materials and the apathy of the faculty who relied on outdated teaching methods, but they also suggested the student “disorder” stemmed from too much free time.Footnote 94 Sometimes, however, investigators found evidence of misconduct, as was the case in Granada. After interviewing over a dozen students and organizing face-to-face meetings between Professor Rosales and the four young women who accused him of harassment, the ministry's investigator concluded that Rosales had violated several of the ministry's regulations.Footnote 95 The investigations were by no means flawless—often teachers were interviewed in the presence of the school director—but for the most part the bureaucrats seemed genuinely interested in uncovering the sources of tension.Footnote 96

In another sign of the students’ budding power, ministry officials immediately attempted to dialogue with the strikers. In Matagalpa, the students even set the tone for the negotiations. They initially rebuffed the ministry's representatives, claiming that they lacked proper credentials. The next day when the bureaucrats came back with not only the requested documentation but also the local Guardia Nacional commander and the bishop, students still refused to meet with them. On the third day, officials finally sat down with the student leaders, who presented them with 14 grievances. The ministry representatives reported that they discussed each of the students demands, which included the removal of the director and three other employees, the right to organize a student council, and a guarantee of no reprisals, but no agreement was reached.Footnote 97 The strike thus went on and so did the negotiations. Eventually, parents, students, church officials, and faculty and their spouses were participating, and on one occasion, parents stayed talking with the minister of education herself until 11:00 pm.Footnote 98 In Jinotega, parents, students, the school director, ministry officials, and even the regional Guardia Nacional commander participated in negotiations that lasted six hours.Footnote 99

Such lengthy negotiations are surprising, given the regime's willingness to use force, and they underscore the powerful movement young people were building. The Guardia Nacional after all had broken up student protests before—had even arrested youth on their campuses for subversive activities.Footnote 100 During the 1976 protests, officials, and even other students accused the protesters of leftist subversion.Footnote 101 Considering that the country was still under a state of siege, with constitutional guarantees suspended, such charges were potentially very dangerous. Yet it appears that only the students in Matagalpa were dislodged by the military. The rest of the occupations seem to have been resolved without force. When the Guardia Nacional did try to intimidate protesters, and even when students were expelled for their political activities, parents quickly got involved and complained to the Ministry of Education and the media. In part, the lack of violence against students during the 1976 strikes could be attributed to the fact that the military was focused on rooting out the guerrilla and their supporters in the countryside.Footnote 102 The regime's restrained approach to the strikes of 1976 thus speaks to the special power these teenagers had to mobilize their societies, the apparently “apolitical” nature of their protests, and a Ministry of Education that was willing to negotiate.

Moreover, whatever the charges of subversion that were lobbed against them, students never went off message: their demands remained strictly institutional. Even though they were cognizant of similar struggles happening elsewhere, each strike that year was against a single director, or a handful of teachers. Disciplined young activists consciously framed the protest to appeal to a wide audience. Because they never mentioned Somoza, or the Sandinistas, for that matter, their protests were relatively safe for parents and friends to join and for newspapers to cover in spite of the regime's censorship.

Under extraordinary pressure from students, parents, communities, and the media, representatives of the Ministry of Education sat down to negotiate, and the protesters won many of their demands. The ministry initiated financial audits, sent better equipment, and promised greater curricular oversight. Students also won the right to organize their own groups, and the ministry recommended schools work on improving communication with parents and the community.Footnote 103 Directors and teachers were transferred (although rarely fired). Even Emilio Sobalvarro, a relative of the director of the Ministry of Education, was forced out in Matagalpa, and the INEP received a new director.

However, the student strikes did not reform the education system or the Ministry of Education. For one, making promises was not the same thing as fulfilling them. In Jinotega, ministry officials had promised to look into the Instituto Nacional Benjamín Zeledón's finances and release information on the school's accounts, but three weeks later these measures had not been taken, and students were threatening to strike again.Footnote 104 Moreover, abusive personnel were not fired. Months after the strike, Sobalvarro received a promotion to become the national director of primary education.Footnote 105 In a more egregious case, officials removed Professor Rosales, the teacher who sexually harassed his students, but recommended he be transferred to a school “that has not had a strike this year.”Footnote 106

Rosales's fate illustrates the clear limits of popular mobilization in authoritarian Nicaragua. On the one hand, the sheer number of students affected by the strikes meant that the state was compelled to respond to education-based protests. On the other hand, it was precisely their capacity to create disorder that prompted the Ministry of Education to promote measures that limited student organizing on campuses throughout the country. Blaming older students for the unrest, the official investigating the strikes in Jinotega suggested breaking up the class schedule so that the senior students did not take all their classes at the same time. That investigator also believed students had too much time on their hands, so he suggested the school offer extracurricular activities to distract them.Footnote 107 The most drastic measure many administrators adopted, however, was the threat of sudden expulsion for any further acts of “indiscipline” or participation in “movements.” Many of the strikes had won promises of no retaliation, so this policy seemed designed to intimidate both students and parents, who in at least one instance were forced to sign a letter acknowledging the new rule.Footnote 108 The ministry thus offered concessions at the very same time it tightened control. In this way, the state quietly undermined student efforts to create more democratic campuses.

Seedbeds of Revolution

Such regulations, however, backfired. The student strikes in 1976 had highlighted the power of collective action, and youth at campuses across the country would begin taking more dramatic and overtly anti-Somocista actions. A generation of young people had become aware of their ability to make demands on the state and destabilize their society. They had become activists and organizers. The 1976 protests underscore the key role that educational inequity can play in catalyzing political consciousness, spurring political action, and building public power.

To be sure, some of the students who participated in the 1976 strikes were already anti-regime activists, if not Sandinista militants, and saw their actions as part of the larger struggle against the dictatorship. José González, a Sandinista secondary student at the INEP who helped found the AES in Matagalpa in the mid-1970s, recalled:

In ’76, we organized students in the largest strike in the history of secondary [education] in Nicaragua. We confronted the Somocista authorities at the time: Alba Rivera, Emilio Sobalvarro, and then vice minister [in the Ministry of Education] Chavarría. We didn't organize just the students at the Instituto Eliseo Picado, but also those in Boaco, Estelí, and Jinotega to spread revolutionary ideas, because Matagalpa really was a seedbed of revolution.Footnote 109

No archival sources exist to suggest that students were demanding revolutionary change during the 1976 strikes, but it is significant that that is how González remembers their efforts. It confirms the utility of educational grievances as an organizing tool against the regime. Moreover, it suggests that even specific educational issues had revolutionary undertones: students were learning how to challenge local authorities and confronting regime-appointed bureaucrats. They were organizing themselves and making demands on a state that had long ignored calls for reform. Other students confirm that for them the school protests were a conscious but clandestine tool for attacking the regime. Leonardo Mora, who grew up on the Atlantic Coast and was a member of the FER in the late 1970s, recalled that at his school, “We first started [organizing] in a way that the dictatorship would not recognize. We began with group associations. We would get together to improve our schooling, but the goal was to participate in the struggle.”Footnote 110 School-based activism then provided anti-Somocista youth with a way to challenge the dictatorship.

For others though, the strikes of 1976 were their first foray into political action, and after the protests ended they began to expand their political involvement. Francisco Guerrero, who studied at the Instituto Nacional de Boaco in the mid-1970s, recalled, “When they started organizing the struggle in my school . . . I did not have political clarity. . . . I did not know what it meant to organize, nor what a student could ask for.” He first became involved in the school's student council during the 1976 protest against the school's director, who students believed was embezzling funds. Even though they did not win their demands, Francisco remembered that “From that moment, the kids on the Student Council [Directiva Central] began to play a different role.” Students began talking about economic conditions and organizing study circles. They even occupied their campus in solidarity with campesinos struggling for land. After that, Francisco recalled “I became more linked in.”Footnote 111 For students like Francisco, school protests catalyzed their political consciousness. Their demand for student rights led them into direct confrontation with a repressive regime and helped them connect their specific struggle to the wider fight for social and economic justice.Footnote 112

That political trajectory had certainly been the goal for the Sandinista militants who were organizing among secondary students, and their efforts paid off. After the 1976 protests, youth at campuses across the country began formalizing their organizations. Students at other schools began forming their own Associations of Secondary Students (AES) after 1976. By 1979, the AES would be a highly organized nationwide network with branches at national institutes in almost all of Nicaragua's cities. By then, the group was campaigning for the freedom of Sandinista political prisoners as well as organizing festivals of revolutionary poetry and music.Footnote 113 Students had proven that strikes were powerful tools, and they would continue to deploy them toward new ends.

Young activists learned quickly that democratic schools could not exist within an undemocratic society. In fact, the regime doubled-down on authoritarian campus practices at the same time that it was intensifying broader repression, and students began linking the two causes. In April 1978, Nicaragua was again rocked by massive student strikes, but this time, student rage against the regime was front and center. That month, youth in universities, secondary schools, and even primary schools protested the treatment of Sandinista political prisoners and the presence of spies on their campuses. Sandinista university students helped these strikes spread rapidly to schools across the country. Humberto Román, who worked with secondary students in Masaya during this period, recalled that the Sandinista leadership hoped these strikes would spur wider political mobilization.Footnote 114 They were right. Once again, families and communities sprang into action to protect their children, organizing parental committees, providing logistical support, and denouncing the regime's violent responses. The military brutally ejected protesters from schools and shot at students, forcing them to back down but radicalizing them in the process.Footnote 115

In the late 1970s, secondary schools served as the grounds for experiments in both democratic organizing and authoritarian repression. Students learned how to stage protests, mobilize communities, and negotiate with government representatives. The Ministry of Education, meanwhile, tried out new methods of control: restructuring schedules and instituting a zero-tolerance policy for student strikes. When those strategies failed, they turned to the military to quell dissent. As the regime became increasingly violent, the student movement would follow its lead.

Conclusion

By 1979, teenagers were making contact bombs in their secondary school classrooms and attacking the soldiers who patrolled their neighborhoods.Footnote 116 By then, a full-scale insurrection was brewing, and young people had become the backbone of the urban revolutionary movement. The 1976 strikes help explain how they got there. That year, students across the country rose up against school administrators, small-scale dictators in their own right, and demanded transparent governance and democratic campuses. Their actions revealed that educational issues provided a powerful catalyst for wider political activism. As people from across class and age groups came together to support student demands for more democratic schools, they created an organizing infrastructure that the FSLN could build on in later years.

In the final tally, students at individual schools won better resources, but the strikes were unable to address the larger problem of corruption and inefficiency that plagued the Ministry of Education. What the strikes did do was reveal the power of student mobilization—its capacity to spread quickly to other schools and other sectors of society and to pass under the radar of censors. In these confrontations with the Ministry of Education, teenagers learned how to organize themselves, build alliances, and craft messages. In so doing, they began reshaping power relations at the local level, replacing authoritarian school directors and promoting parental (and student) involvement in the schools. They showed their communities that it was possible to engage with the state, to make demands and win concessions. In other words, the 1976 strikes politicized a generation of students and their parents.

The protests that year were thus a precursor to wider revolution. They illustrate how movements are built. Not only did the strikes lay the groundwork for a much more coherent national student movement, but they also prepared parents and communities for greater mobilization. All of this became apparent in the 1978 strikes that ended in widespread violence, and which followed many of the same patterns as 1976. It is not a coincidence that the secondary student movement became more organized and politicized after the 1976 strikes. They had won the promise of more democratic schools; now they would set their sights on creating a more democratic nation, even if it meant taking up arms to do so.