In October of 1827, a British frigate called the Eden arrived off the shores of a small island in West Africa near the Cameroon coast. The optimistic name for the ship reflected the hopes of British policymakers looking to suppress the foreign slave trade in the region by establishing a new settlement. On the British captain's map the island in question was called Fernando Po, named after the first European to have seen it. As the Eden made its way slowly around the 120-mile perimeter, surveying the shoreline, the newcomers commented on the dense vegetation broken only by the two impressive mountain peaks. Local islanders watched the vessel warily. When it finally stopped on the western shore, three canoes immediately embarked to confront and question the strangers. The captain recorded his astonishment at the appearance of his interrogators, with hair coated in clay and palm oil, and hats adorned with seashells. They seemed nonplussed at his appearance, or his ship. Their first query for him was whether he had come “to buy yams or men or to fight.”Footnote 1

The captain in question was William Fitzwilliam Owen, a seasoned Royal Navy officer who had made a name for himself as a hydrographer of the African mainland coast. The local islanders with whom he was dealing were the indigenous Bubi, a Bantu-speaking people who had clearly dealt with outsiders, including Europeans, before. In what would become a defining transaction, Owen traded an eight-inch piece of iron hoop for twenty pounds of yams. Although neither party knew it, this interaction marked the beginning of a new chapter in the history of Fernando Po. Unlike previous encounters, these outsiders had come to stay. They would soon begin construction of a permanent settlement called Clarence Town. And within weeks they would be joined by hundreds of liberated slaves, freed by British antislavery patrols in the area. Even after the official suppression project collapsed a few years later, many of these new settlers remained, evolving into a creole community that would eventually dominate the entire island by the end of the century.Footnote 2 It is this later history that infuses Owen's landing in 1827 with such significance, as it marks the beginning of Fernando Po's colonial period.

While Owen's landing was important for the history of the island, it also allows us to examine this history in the context of Britain's campaign to suppress the slave trade, and analyse more fully how abolitionist policies manifested “on the ground” in Africa. This connection between abolitionism and imperialism has been a fruitful way of better understanding how each operated in an African setting.Footnote 3 The deepest scholarship on this theme has focused on Sierra Leone, arguably the most visible example of British abolitionist ambitions in West Africa.Footnote 4 Additional case studies have examined other antislavery projects, including failed ones such as the Niger Expedition of 1841–42, as a way to better understand European “dreams” (to use Howard Temperley's word) about, and for, Africa in the age of emancipation.Footnote 5 More indirect linkages between abolitionism and imperialism have been made by seeing European concerns over slavery in Africa as a convenient justification for various aggressive actions there, most notably the land grabbing that ensued across the continent in the last decades of the nineteenth century as part of the “Scramble.”Footnote 6 More recently, historians such as Richard Huzzey have begun to analyse the relationship between antislavery and empire more directly, outlining how this connection affected Victorian colonial policy as well as domestic politics.Footnote 7

The Royal Navy, in particular, has been a particularly useful analytical tool to examine the overlapping goals of abolition and imperialism. Mary Wills’ work on the Royal Navy has found “Britain's anti-slavery efforts and imperial agendas in the Atlantic world were bound tightly together . . . with the Royal Navy and its officers playing a pivotal role in delivering abolitionist goals, at sea and on land.”Footnote 8 Other scholars have examined some specific ways in which British naval forces advanced these agendas. For example, Robin Law has shown how British officers used abolition as a justification for using military force against two West African port cities in the early 1850s, Ouidah and Lagos, in violation of international law.Footnote 9

On the one hand, the founding of Clarence Town provides another useful example to illustrate the relationship between, and impact of, both antislavery and imperialism in West Africa. It was planned as a British abolitionist colony, replacing Sierra Leone as a home for liberated slaves. The Colonial Office and Admiralty had a blueprint for moving their suppression operations. The officer-on-the-spot, Owen, built the settlement. On the other hand, this story complicates this historiography. Clarence Town never became a British possession or colony. The courts of mixed commission, which tried captured slavers, never relocated from Sierra Leone. And Owen's actions often ran counter to official policy. Indeed, his decision to (illegally) land liberated slaves helped both scuttle the project and unwittingly formed the core of a new African colonial elite on the island. What started as a European dream ended as a new, mixed–West African reality.

One important insight from this story is that suppression, as one facet of abolitionism, was a force of disruption that created the conditions for imperial activity, but not so in ways that were intentional or predictable. Multiple actors were able to take advantage of these conditions; beyond Owen, these would include other Royal Navy captains patrolling the area, other African regional merchant-rulers, local Bubi chiefs, and eventually leaders among the ex-slave community in Clarence Town. Thus a more useful interpretive lens would be an updated version of Galbraith's “turbulent frontier” thesis, which privileges the periphery as well as contingency in the imperial expansion process.Footnote 10 This particular chapter in Fernando Po's history allows us to see the life cycle (so to speak) of imperialism, how policy in the metropole was translated through the officials on the spot and mitigated by the conditions on the ground. It also provides a more holistic view of antislavery and imperialism in Africa. Instead of looking at both from the vantage point of colonial policy and assessing their impact in Africa in terms of successes, failures, motivations, and justifications, here we can see an example of how such policies were translated through the decisions of both officials such as Owen and the local inhabitants in the area, creating something wholly new.

In addition to his regular dispatches back to various government offices involved in the endeavour, Owen kept a private journal which allows us a unique window into documenting this colonial history, including what is probably the earliest detailed accounts of the land and indigenous peoples. Hitherto untapped, this resource helps shed light on the history of the island at the moment of contact; how its local population began a continuous interaction with Europeans and other West Africans, and the immediate results of this connection between their worlds. Such a source is a welcome find for scholars of an island whose available sources are few. What little documented history is available on Fernando Po (now called Bioko and part of Equatorial Guinea) has focused far more on its tumultuous political evolution in the twentieth century than of its precolonial or early colonial period.Footnote 11 The history of the indigenous people, the Bubi, in particular, has challenged historians because sources are both scarce and foreign. As Ibrahim Sundiata, the island's most prominent scholar, has noted: “Unfortunately, it is only through the prism of colonial culture that we can attempt to see the lineaments of the precolonial . . . much of what we know of Bubi culture can be obtained only by consulting the written records of outsiders.”Footnote 12

Here we have a source from colonial culture in almost its purest form—a European ship captain's personal diary written during the settlement of a foreign island. As with all encounter narratives, extreme care must be taken. Owen was a hydrographer by training, not an anthropologist. His comments are often sweeping and generalising, not to mention patronising. Although vehemently opposed to the trade in slaves, he held many of the same racial attitudes about non-Europeans that many of his contemporaries did. At the same time, however, his journal record highlights that Bubi decisions influenced the colony's development at every stage.

The Geography and Early History of Fernando Po

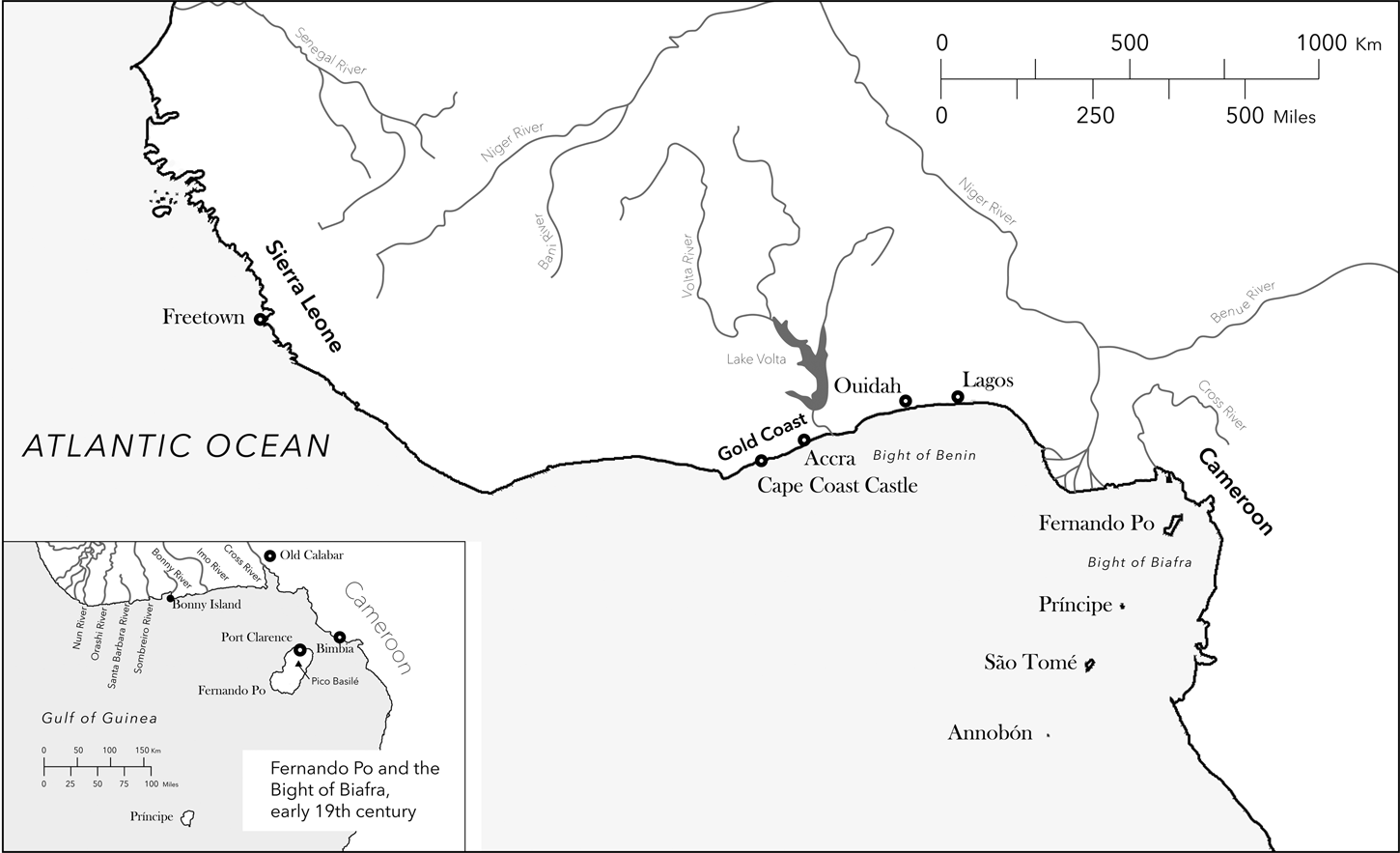

At just over eight hundred square miles, Fernando Po is the largest in a line of four volcanic islands in the Bight of Biafra,Footnote 13 with São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón comprising the rest. Dense forest covers much of the island. It is very wet, with the southern tip receiving as much as four hundred inches of rain per annum. The rainy season lasts most of the year except December to January. The most striking geographical feature is Pico Basile, a peak that stands nearly 10,000 feet high.Footnote 14 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The West African Coast, early nineteenth century. Image by Bruno B. Berry.

The indigenous Bubi are a Western Bantu-speaking people who migrated in multiple waves from the Cameroon and Rio Muni regions.Footnote 15 “Bubi” is the native word for man, apparently introduced into English by a British captain visiting the island in 1821. They were monogamous, matrilineal, and monotheistic, with an economy centred on small-scale yam cultivation, supplemented with stock-raising. Unlike other Bantu-speaking peoples in West Africa, the Bubi did not produce iron. The rugged terrain kept them fragmented politically and linguistically.Footnote 16

Europeans would discover the island for themselves in the fifteenth century, but until the nineteenth century, it would remain a possession on paper only. The explorers Lope Gonsalvez and Fernão do Pó claimed it in 1472 for Portugal, which mostly ignored it in favour of neighbouring São Tomé. Prevailing winds and currents favoured the latter, which became an important early sugar producer as well as an administrative hub for Portuguese imperial and slaving operations in Kongo and Angola. Other factors which deterred European settlement on Fernando Po included a more rugged environment and an indigenous population willing to defend it from outsiders.Footnote 17 In the 1778 Treaty of El Pardo the Portuguese ceded Fernando Po and Annobón to Spain in exchange for territory bordering Brazil. The Spanish attempted but failed to colonise the island in that year in an expedition led by Felipe José, Count o fargelejos de Santo y Freire.Footnote 18 When Owen landed on the island almost fifty years later, he found glass and the remains of four abandoned plantations from the Spanish settlement, the only evidence noted of European colonisation prior to his arrival.

The initial question put to Owen as to whether he had come to buy “yams or men or to fight” speaks volumes about the Bubi's relationship to the larger West African world in the 1820s. Among other points, it underlines the fact that they maintained a wary contact with regional merchants, but hitherto had been able to repulse or escape the large-scale trade in slaves.Footnote 19 Until 1827, Fernando Po had been an island relatively isolated from the slave trade and, despite earlier attempts by Portugal and Spain, European colonisation. Owen's arrival marks the end of this isolation.

British Interests in the Bight of Biafra

In the early nineteenth century the Bight of Biafra became an increasingly desirable region for a number of British interests. Abolitionists hoped to stop one of the principal sources of the Atlantic slave trade along the West African coast. Explorers and geographers wished to confirm or deny decades of speculation that the source of the Delta rivers was, in fact, part of the great Niger River. Merchants hoped to exploit the vast palm oil resources of the region.Footnote 20

By the late 1820s, these interests dovetailed with the British government's own anti-slave-trade campaign. Since the late seventeenth century this region of Africa had become the largest source of slaves north of the equator. By the time of the Napoleonic Wars, this portion peaked at between 14 and 24 percent of the total transatlantic slave trade, or between 15,000 and 25,000 slave embarkations per year.Footnote 21 Once the biggest traders in these slaves, the British outlawed the trade in 1807. They then sought to suppress the trade from other countries through a series of bilateral treaties. These agreements stipulated the use of navies to enforce them, although in practice it was overwhelmingly only the British navy which conducted patrols in West Africa. Once captured, suspected illegal slavers were taken to a “court of mixed commission,” with judges from Britain and the country of the suspected slaver. Condemned slavers would be impounded, their crews released, and their slaves freed.Footnote 22 Because the majority of slaves continued to come out of the Bight of Biafra, the British continued their presence there as would-be suppressors. The antislavery arm of the Royal Navy was dubbed the “African Squadron.”Footnote 23

The initial location for the naval base and home for the courts in the abolitionist colony of Sierra Leone was more a product of the early commanding role that British antislavery activists had in matters of slave trade policy than it was of practical necessity. After leading the campaign to end the British slave trade, the abolitionists took the lead in suppression as well.Footnote 24 Their colony of Sierra Leone seemed a natural location for a West African base mainly because it had been a home for freed British slaves since its founding in 1787. However, between disease and a marshy terrain which limited agricultural productivity, the colony struggled to survive even from its early days. The steady influx of newly liberated slaves from suppression captures would exacerbate these problems greatly and spark a debate about its suitability.Footnote 25

Criticism of the location and calls for a move closer to the Slave Coast began almost immediately after the suppression campaign got underway, and came from a broad range of sources. In 1812 a minority report published within a larger government inquiry into the state of Britain's African settlements noted that the antislavery ships should be based further east, where the majority of slavers were captured.Footnote 26 The Quarterly Review commented that Sierra Leone was “certainly not held in the highest estimation by the officers of the British navy.”Footnote 27 In 1819, the Portuguese and Spanish governments petitioned the Foreign Office for a healthier location for the court of mixed commission. British commissioners in Sierra Leone itself complained of delays due to illness and death.Footnote 28 MPs charged that “even those who escape the grave, linger out a painful and miserable existence.”Footnote 29 And of course proslavery forces in the metropole who had opposed the very existence of the colony happily kept these problems in the public eye.Footnote 30

While various groups had voiced their interest in acquiring Fernando Po since the days of the Napoleonic Wars, the British Foreign Office was not ready to act until the mid-1820s. In 1825, the Gold Coast Trading and Mining Company petitioned the government to establish a settlement on the island. Interestingly their argument rested both on the commercial advantage as well as the antislavery potential of the island.Footnote 31 Two months later the Spanish and Portuguese governments again requested that the court of mixed commission in Sierra Leone be moved. At this point Foreign Secretary George Canning responded that he had only lately learned of Fernando Po, an island “wholly without any European occupation . . . situated in the heart of the slave trade,” with a “salubrious” climate, and soil “sufficiently fertile”; therefore, he was ready to move forward with relocation.Footnote 32 That the island was still a Spanish possession did not slow down the preparations. Indeed, by January of the next year Lord Bathurst, the Colonial Secretary, sent instructions for the settlement to the AdmiraltyFootnote 33 and by July Captain Owen was leaving Portsmouth in the Eden.

Owen, the Bubi, and the Establishment of Clarence

Owen was selected to lead the project for both professional and personal qualities. An illegitimate son of Commander William Owen, R.N., William Fitzwilliam rose through the ranks of the Royal Navy through his own hard work and the occasional good word to the Admiralty from his influential half-brother, Robert.Footnote 34 He saw naval action throughout the Napoleonic Wars, mainly in the Dutch East Indies, where he became the “naval strong arm” of Thomas Stamford Raffles, then governor of Java. Here Owen developed a strong hatred of the slave trade (perhaps influenced by Raffles's own views), which soon developed into a personal theory that the slave trade could be destroyed through the power of the Royal Navy.Footnote 35 He also discovered his talent for hydrography in this period through some independent surveying of the Malaya coast. This talent turned into a life-long occupation after the war, as he spent the rest of his career conducting surveys which spanned four continents that are still praised today for their accuracy. His crowning achievement was his African survey in which he mapped approximately 20,000 miles of uncharted or mischarted coastline, from Arabia to the Gambia River.Footnote 36

While undoubtedly a man of great organisational and charting capabilities, Owen's career is a case study in the imperial power of evangelical antislavery, particularly in its capacity to ignore or obliterate established norms and laws on the frontier. On the one hand, his religious devotion informed his strict sense of duty and sacrifice as well as his abolitionism. On the other, it gave him the moral self-assurance to ignore instructions, directives, orders, or even laws with which he disagreed. In the East Indies he illegally detained slavers. During his African survey, he annexed Mombasa and outlawed slavery there. So it should have come as no surprise that he would defy his instructions on Fernando Po, with far-reaching consequences.

At the time of his appointment, though, no one could question Owen's African experience, charting abilities, or his antislavery credentials. These, along with some excellent connections, landed him the job of moving the court. One of his connections included the Duke of Clarence (the future King William IV), then First Lord of the Admiralty, who issued the orders that he should lead the project. He was given the dual posts of Superintendent of Fernando Po as well as senior officer in the African Squadron. On 29 July 1827 the Eden left Portsmouth harbour and, after commandeering ships in Sierra Leone and Cape Coast Castle, touched at Fernando Po in October.

After the initial grilling he received regarding his intentions, Owen recorded his own initial description of the Bubi. Even for someone as well travelled as Owen, individual Bubi presented a striking appearance, as his first clumsy description of them indicates:

Their dress is a hat of straw adorned with small shells in the way of beads and some feathers. Their front head [sic] was in some shaved and in all their locks were dressed with a mixture of Red Clay and palm oil hanging on their necks in small locks rendered pendulous by lumps of the sand clay. For Decency a fringe . . . which seemed made of grass or leaf. They have Anklets, Bracelets—and Charms of as many kinds as other African tribes. Their general appearance was of extreme good nature and intelligence. They had not the appearance of stupidity which generally attaches to the slave tribes. They appeared very Athletic.Footnote 37

Owen's portrayal recalls so many other European encounter narratives dating back to Columbus's description of the Taino, which mix admiration and astonishment couched in casually demeaning language. His patronising tone here was reflected more generally through the disparaging names that would later be used by the settlers for individual Bubi: Sly Thieving Dick, Good Tempered Jack, Glutton, and old Hum Hum give a sense. Even the chiefs of the various Bubi tribes could not escape names such as King Cameleon, King Barracouta, or “old Bottlenose.”

Owen selected the northern coast of the island in which to construct the settlement because of its excellent harbour and easy access to timber and fresh water. He traded three bars of new iron hoop from the nearby coastal Bubi community for permission to build, and renamed the surrounding area Clarence Cove. Subsequently he began construction of Clarence Town itself. According to Owen, this was done with the cautious approval of the coastal Bubi, who “watched . . . [the settlement] narrowly. There were not less than a thousand armed men about it to-day.”Footnote 38

Owen constructed the settlement the way he ran a ship: with a strict schedule and discipline. Work commenced at half past four in the morning and ended at half past five in the afternoon, with a two-hour break at midday. Work ended at noon on Saturday and on Sunday none was required. However, failure to attend church service, conducted by Owen, would land one in the stocks. Owen had been granted martial authority by frontier necessity (over the protests of the English artificers), and, in addition to superintendent, took the jobs of accountant, purser, judge, minister, surveyor, and secretary.

Clarence was built with English supplies and Sierra Leonean manpower, both supplemented by Bubi expertise. The original nonindigenous African labour force that Owen had hired from Freetown and Cape Coast Castle included 160 skilled artisans, 100 labourers, and 62 troops from the Royal African Corps. Highlighting the diverse population of the colony, they came from one of three main groups: “fishermen,” who were descendants of the Nova Scotian blacks resettled in Sierra Leone in the late eighteenth century; Kru, a fishing people from Liberia and Ivory Coast known for their hardihood and seamanship; and finally, liberated Africans, who made up the largest number and came from several ethnic backgrounds. Since most of these African labourers planned to stay on the island as settlers, many of them had brought their wives. The few Europeans included the original sailors, some artisans, and a few of the RAC soldiers, including its sergeant.

At the time of his landing Owen estimated that the total Bubi population numbered about fifty thousand, with three main warring confederations each headed by a kokolaku (great man).Footnote 39 Each confederation was made up of smaller communities led by sub-chiefs, who controlled lands in their regions and managed food production. War was a consistent feature of Bubi politics, as groups competed for iron and women.Footnote 40 Owen became part of the political manoeuvring almost immediately as the Bubi faction that had granted him the land for Clarence made it known that they hoped to secure an ally against a rival in the interior “who always made war upon them as soon as ships left the bay.”Footnote 41 Later that month an intertribal conflict nearly broke out over the newcomers. When touring Bottlenose Point a few miles to the east, “a party of five or six hundred came down on the opposite point and made war like signs and threatening to kill our people. They were defied in turn, by those of Bottlenose.”Footnote 42 By this point Owen had taken the title of kokolaku as well. In January, several chiefs arrived at the settlement to “establish and perfect peace and brotherhood with the newcomers,” and then invited him to fire muskets at their rivals to the east so that “we might get as many of their women as we pleased to seize.”Footnote 43

The basis of the island's economy was yam farming, but Owen later reported that most Bubi families also raised palm oil gardens, jungle fowl, sheep, and goats. They hunted wild cattle as well. They had no knowledge of pottery making, iron smelting, weaving, and wood carving, which to Owen explained their “insatiable” desire for iron of any sort. He reported one incident in which two Bubi men fought each other for fifteen minutes in the sea over a single piece of iron.Footnote 44 They had canoes but Owen speculated that these were only used for coastal travel since there was no evidence of them ever leaving the island.

Owen noted two main classes among the Bubi, nobles and commoners. (He did not use the native words for these groups, baita and babala.Footnote 45) The ruling class distinguished itself with two colours of clay, yellow on the body and red in the hair, as well as sheep or goat horns attached to their straw hats. The only mention of slavery in Owen's diary was in December 1827 when three men from São Tomé claimed to be held as slaves by a local chief.Footnote 46

The new settlement never became self-sustaining, even when Owen later began landing stores from captured slavers. Ironically its dependence on island and regional suppliers accelerated Fernando Po's integration into the larger Biafran commercial market. Initially the newcomers could rely on local help to survive. Less than two months after landing, the Bubi were instructing the settlers on yam planting, and various yam stores were constructed around the settlement. Even with this, settlers still had to trade with local Bubi to supplement. A border market on the edge of Clarence opened in late November. The settlers traded manufactures, particularly iron hoop, iron bar, knives, and some trinkets for food, especially yams and livestock. Characteristically, Owen applied strict rules for trade: all commerce had to go through the Clarence market; absolutely no alcohol or firearms were to be introduced to the island; trade between Fernando Po and the coastal areas would be conducted by one merchant, John Smith. The settlers also discovered the value of Fernando Poan palm oil, which was of equal quality to mainland oil, but one-twelfth the price. By February Owen noted that the production had gone from one to two tons a day, to be shipped to Sierra Leone.Footnote 47

Local supply and trade could not keep up with the settlement's growth once Owen began landing liberated captives from slavers. Such growth forced him to trade with the regional suppliers from as far west as Accra along the Gold Coast to the Bimbia markets in Cameroon, just northeast of Fernando Po. The biggest supplier came from Old Calabar, just north at the delta of the Cross River. Owen travelled himself (instead of his merchant, John Smith) across the channel in mid-March 1828 to meet its ruler, Duke Ephraim, and negotiated a trade agreement. While Owen privately derided the Duke as a “wary rogue,” he understood that this was the most powerful man in the entire Delta region, and that the long-term success of Clarence Town depended upon his good will. The Duke was the leader of the Efik tribe and became the most influential of the merchant-kings of Old Calabar.Footnote 48 By this time he held a near monopoly on all external trade in the region, received all “comey” (customs duties), retained a large stock of slaves, and had an impeccable record of credit-worthiness among European traders.Footnote 49 The following February the Duke signed a contract admitting debt for $36,520. At the same time, Owen was careful to note that he could muster 150 canoes of about a gun each and between three and four thousand warriors. In light of these realities, Owen made an agreement to trade British manufactures for food and stock.

The administration of justice was a traditional responsibility of the kokolaku, which nicely complemented Owen's colonial authority as the settlement's superintendent. Within two months of landing he had established a superintendent's court for natives, settlers, and British traders. When the duties here became too much, he appointed two justices of the peace to help with his judicial workload. According to his diary, justice was, on the whole, managed amicably, if more and more autocratically, while Owen was superintendent. For example, when a group of neighbouring villagers accused some of the settlers of stealing sheep, Owen immediately dispatched a search party, found the accused, had the villagers identify them, and then had them flogged to the villagers’ satisfaction. Likewise, when a Bubi man had been caught stealing from the Eden, Owen initially deferred to island justice, until he learned that the man was to lose his hand. Owen intervened and had him flogged instead. He also mentions granting asylum for domestic abuse cases or even political refugees and their pets, although it did not always end well for the latter. In mid-November 1828 Owen granted sanctuary to a local chief named “King Cutthroat.” The following January he updated his journal noting that the chief's dog, Spot, had killed his (Owen's) cat. He ordered all the natives temporarily out of the settlement and had the dog hanged.Footnote 50

After less than a year the settlement seemed secure and Owen's authority unchallenged. By this time he had annexed and expanded the settlement, absorbing some Bubi families within his jurisdiction. He made sure it was clear that “the Captain was the Chief of all the land indicated” in the expansion. These moves reflected his growing political influence among the Bubi, a position he enhanced by maintaining a monopoly of firearms. He admitted their importance when he let a deserter go rather than get Bubi assistance in his capture. Owen had determined that losing him was preferable to their “overcoming this fear of his arms on which perhaps rests much of our security.”Footnote 51

Mortality rates were tolerable for a new settlement—by April 1828 Owen reported eighteen deaths amongst the settlers: nine by disease (mostly fever) and nine by accident (usually alcohol-related), murder, or an unnamed cause.Footnote 52 At the one-year mark, thirty-seven deaths had been reported in his journal, with a population of 679, excluding the Bubi families in his jurisdiction. A major blow came in February 1829 when his second in command and “firm friend,” Captain H. Cooke Harrison, died from being bled too much from fever. Owen lamented “our insufficient knowledge of medicine.”Footnote 53

The difficulties that existed between the Bubi and the newcomers were more cultural, at least from Owen's point of view. One of the important rituals marking significant occasions between the island tribes involved sacrificing a ram and eating various parts of it raw, or nearly raw, to which Owen’ dismissively commented “nothing could be more Canniballish.”Footnote 54 The clothing and sexual norms of Bubi women, especially married women, were also disturbing. In one tribe Owen found that they “kiss freely . . . in the presence of their husbands who are flattered by this mark of friendship. . . . A belt and a fig leaf they all wear, but it is a mere apology and they are flattered to have it removed as a mark of desire or admiration.”Footnote 55 Owen noted that generally, the Bubi “resembled much in their habits to the South Sea Islanders as inconveniently curious and as easy about the sex. Indeed their men invited ours to go into the Bush with their women.”Footnote 56 On the other hand, Owen did not protest when King Cove brought a prostitute on board and offered her to him; according to his diary he declined but not with any of the moral outrage he felt elsewhere.

Slave Trade Suppression and Its Consequences for Fernando Po

Despite the differences between the settlers and the local population over cultural norms, judicial policies, or the use of armed force, Clarence was, on the whole, integrated on the island in a relatively stable and secure manner by 1829, and simply became one of several competing political and military powers. Even while remaining dependent on Bubi and regional suppliers, Owen was able to stake out an independent authority and lay the groundwork for the future dominance of Clarence by expanding his political, economic, and judicial influence farther afield. But it was his decision to land liberated Africans from captured slavers that would have the most far-reaching consequences for Fernando Po. Since the courts had not officially moved yet such measures were illegal. In the short term these actions would get him removed from his post and terminate the British plan to move the courts altogether. However, two years of landing and freeing slaves would form the core of a new, permanent, and ultimately ascendant population—“the Colonial Nucleus” in Sundiata's terms—which dominated Fernando Po in the second half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 57

Theoretically there should have been no European slavers in the region. By 1827 Britain had signed treaties with Spain, Portugal, and Brazil which banned the slave trade north of the Equator, and allowed the British African Squadron to stop suspected violators. Only American and French ships could not be detained, although both countries had also outlawed the slave trade themselves in 1807 and 1820, respectively. None of these legal measures mattered, however, as a black market thrived, as well as the elaborate ruses that accompany illegal trade. Squadron commanders complained throughout this period of various subterfuges. False passports were made out by corrupt Portuguese officials in Príncipe or São Tomé. Other slave ship masters claimed the need for repairs or supplies in the region even when, as one Squadron officer noted, “these daring wretches . . . are detected with part of their cargoes landed.”Footnote 58 The more resourceful slavers would hire an American or Frenchman to play-act the master should their vessel be stopped.

Thus finding illegal slavers would not be a problem, as Owen himself discovered when his steamship African caught two Brazilian ships before even landing at Fernando Po. The rich supply of illegal slavers coupled with Owen's strong abolitionist beliefs provided the inspiration to create his own private fleet of suppression vessels. By January 1828 Owen had begun a regular patrol of Bimbia, Old Calabar, and Bonny (just west of Old Calabar at the mouth of the Bonny River) with a mini-squadron of eight vessels he had amassed with commandeered Squadron ships and captured slavers.

Although the court had yet to move officially, Owen usually took captured slavers to Fernando Po to land a large portion of slaves, and sometimes even the crew. On the face of it, very real health concerns dictated as much, as the appalling stories of other captures in this area attested. For example, in September 1827, the Redaring caught a slaver off of Old Calabar and as they escorted it to Sierra Leone, 193 out of 196 of its captives died. A few months earlier Captain Septimus Arabin of HMS North Star captured the Spanish schooner Emelia in the Bonny River with 282 slaves; only 177 made it to Sierra Leone. Such horrifying mortality rates help explain why court officials were happy to report, as they did in January 1827, that “only nineteen” captives had died in a Spanish ship carrying 309 slaves.Footnote 59

These shocking stories underline one of the main reasons the court was moving in the first place. However, Owen seems to have had other motives for stopping at Fernando Po first as well, motives which again highlight his willingness to work outside of established laws and instructions. When Owen caught the Emprendodor in June 1828, it carried three healthy slaves aboard. Yet he landed them “for greater security and to [deny] their being tampered with by the Spanish master.”Footnote 60 Of the hundreds of liberated Africans that Owen landed over the course of his superintendence, the able-bodied received a blanket and a yard and a half of sail cloth and conspicuously fell in among the labourers of the settlement working for nine pence a day. Healthy females landed often became the wives of settlers. Children could be adopted by either settler or Bubi families. (If they remained orphaned they would be sent on to Sierra Leone.) After signing a “parole of honour,” slaver crews filled in positions where their skills allowed. Indeed, Owen admitted that he often found these crews to be more competent then those directly from Europe, as was the case with an assistant surgeon about whom he scoffed “comes to me already subdued by a puerile dread of [the] African climate.”Footnote 61 Instead he preferred the three former slavers he had already hired.

Provisions and equipment from these slave ships were also landed and either used or sold. Sometimes whole slave ships were used before being sent to Sierra Leone for trial. For example, Owen's first visit to Old Calabar was in the Victoria in March 1828, which had been captured only a month earlier (and all of its stores landed). Thereafter he used it as his own patrol vessel until it was ordered to Sierra Leone in mid-May.

Clarence became an instant hub for other Squadron patrols in the area, which were used to the nearest port being Ouidah, more than a week's sailing away. Squadron commanders used Fernando Po to exchange information, resupply, enlist Owen's vessels for additional support, and most significantly, to land liberated Africans. Captain Arabin—the officer in charge during the disastrous Emilia affair—frequented Clarence the most after Owen's arrival, always attempting to land as many freed slaves as possible. For instance, in November 1828, he captured the Brazilian schooner Campeodor with 381 slaves aboard. He petitioned Owen to land 200 of them, of which Owen accepted 151.Footnote 62

The decision to land liberated slaves had enormous consequences on the settler population and ultimately the long-term trajectory of Fernando Po's development. By March 1829 the population had reached 1,277, largely due to the accelerated landings of captives from captured slavers. Owen recorded the following population breakdown for Clarence:

26 Europeans (in establishment)

8 European soldiers

70 European captives (incl. some creoles)

250 captured negro men

100 captured negro boys

86 African soldiers

37 African soldier boys

80 Kroomen [Kru]

50 mechanics’ wives

70 soldiers’ wives

92 captured negro women

116 captured negro girls

58 girls w/soldiers’ wives

20 infants

= 1277

Not surprisingly, complaints about Owen's actions began pouring into the Colonial and Foreign Offices from several fronts. The commissioners in Sierra Leone were furious that Owen was skirting the adjudication process. Landing slaver captives and crews violated both Owen's orders and the treaty between Britain and Spain, which was still technically the owner of the island.Footnote 63 Owen's agent in Sierra Leone warned him that “ever since you left this colony in the Eden the prejudice against the new settlement has considerably increased, and particularly amongst the Mixed Commission Court.”Footnote 64 Owen responded with his usual lack of tact and complaints about a “foul conspiracy” afoot in Sierra Leone to undermine him. Owen had also angered officials in the Colonial Office, the branch now fully in charge of the project, over his failure to keep them informed of progress. He replied that he meant no disrespect and thought his letters to the Admiralty sufficed.Footnote 65 Meanwhile the Foreign Office was fielding complaints from other governments over Owen's aggressive suppression actions, particularly his arrest of their citizens and the seizure of their property. Fed up, the Colonial Office ordered his removal from the project in December 1828. His replacement, Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Nicholls, arrived the following May to take the reins of the project. Owen remained until December 1829, when he left on a new surveying mission to South America. He would never return to Africa again.

The last entries in Owen's journal detail the precipitous decline of Clarence under the new superintendent. Nicholls was a battle-hardened Peninsular War veteran who had most recently been the governor of Ascension. Owen initially found him capable but soon changed his mind as Nicholls strayed from Owen's policies: allowing individual merchants to trade without restrictions, allowing guns and alcohol on the island, the failure to hold church services, the pursuit of his own profit at the expense of the settlement, and the alienation of most of the native Bubi. Worst of all, Nicholls had allowed yellow fever to get on the island. The epidemic first appeared on Owen's own ship, the Eden, in early June, as he prepared to hand over control of Clarence. He quarantined the ship and accelerated his preparations to leave in the hopes that the open sea would help the sick. Four days later Nicholls returned from a resupplying run with yellow fever aboard his ship as well. Yet he insisted on landing the sick. Washing his hands of the matter, Owen departed in July on a long reconnaissance and resupply run to prepare for his final departure. He returned in November 1829 to find

Clarence in a desperate state of decay. . . . Many of all of the trees left standing for ornament and shade were cut down, not removed . . . all the fences were broken down, the garden almost in ruins, all the buildings neglected, the Public stores in the greatest disorder and confusion, with no person in charge of them. Everybody disgusted—in short the Superintendent is mad but it was a mania of cupidity and avarice.Footnote 66

The following years were marked by further decline at the official level and shifting colonial oversight. Clarence limped on under Nicholls’ leadership until 1834 when the Colonial Office ordered the settlement closed.Footnote 67 His second in command, John Beecroft, stayed on as a private company employee, and spent the next decade aiding various explorers and merchants in the Delta region, including the famous Lander brothers.Footnote 68 In 1843 Spain formally reasserted its sovereignty over the island, renamed Clarence Santa Isabel, and appointed Beecroft to be the island's first governor. In 1849 the British government appointed him the first Consul of the Bights of Benin and Biafra.

Ultimately the European claims to Fernando Po, whether British or Spanish, or the officials, whether superintendents or consuls, proved less important than the settlers and the settlement left behind. With the British abandoning their plans for the courts, and the Spanish ignoring it, Fernando Po remained free of official imperial influence. But it did not go back to its semi-isolation prior to Owen's arrival. The successful construction of Clarence ensured a permanent gateway into the larger Euro–West African world, even with the hard times the settlement faced after Owen's departure. The original settlers, mostly the Kru labourers and liberated slaves, formed the core of a new population, “the colonial nucleus” described by Sundiata, which would continue to interact and often rival Bubi communities on the rest of the island.Footnote 69 These were later joined by other regional traders looking to exploit Fernando Po's palm oil resources. Runaways from Clarence would establish new communities in the interior, often coming into conflict with local Bubi. By the 1840s members of the Baptist Missionary Society began arriving to proselytise. The Niger Expedition used the island as a supply base before embarking on its ill-fated journey up the great river.

This integration proved disastrous to the Bubi in the long run. Disease and warfare brought a significant population decline. Those that interacted with Clarence traders were exploited. And while they were able to establish a semblance of unity and even a “Bubi paramountcy” in the second half of the century, it gave way to the ascendance of non-Bubi creoles, many of whom were the descendants of the settlers brought by the Owen mission. By the 1880s they dominated Fernando Po's trade and plantation agriculture.Footnote 70

Documenting the process of settler–Bubi relations from the beginning in the context of Britain's antislavery campaign provides an invaluable window into understanding the start of Fernando Po's colonial period. It adds nuance to our understanding of the complexity of the Bubi polity, and how an outsider like Owen could use those divisions to his advantage. It details the process of solidifying the military, economic, and judicial authority of the newcomers, as well as the crucial decision to land liberated slaves on the island. And it illustrates the disruptive power of antislavery generally, and the suppression campaign specifically, especially when interpreted by enthusiastic men-on-the-spot like Owen.