Introduction

Study of the Early Neolithic in western Europe has established an indisputable link between the spread of new subsistence strategies and technological practices and the movement of human populations from East to West. Previous work highlights the close material connections between northern Italy, southern France, and Mediterranean Spain (Guilaine & Manen, Reference Guilaine, Manen, Whittle and Cummings2007; Bernabeu et al., Reference Bernabeu, Molina, Esquembre, Ortega, Boronat and Barbaza2009, Reference Bernabeu, Manen, Pardo, García-Puchol and Salazar2017; Manen, Reference Manen, Manen, Perrin and Guilaine2014; García-Puchol & Salazar, Reference García-Puchol and Salazar2017). By contrast, the Early Neolithic of the Atlantic regions of the Iberian Peninsula displays a number of distinctive features that derive from its geographic position in the south-western confines of mainland Europe (Guilaine & Veiga Ferreira, Reference Guilaine and Veiga Ferreira1970; Arias, Reference Arias1999; Diniz, Reference Diniz2008; Gibaja & Carvalho, Reference Gibaja and Carvalho2010; Carvalho, Reference Carvalho, Rojo-Guerra, Garrido and García-Martínez2012).

In the coastal regions of central Portugal, the existence of a Mesolithic substrate, mainly identified archaeologically at sheltered estuarine shellmiddens, and the suggestion of a possible chronological overlap between the last hunter-gatherers and the first agriculturalists has had a particularly strong impact on the understanding of the Early Neolithic (e.g. Mendes Corrêa, Reference Mendes Corrêa1934; Russell Cortez, Reference Russell Cortez1953; Roche & Veiga Ferreira, Reference Roche and Veiga Ferreira1967; Tavares da Silva & Soares, Reference Tavares da Silva, Soares, Guilaine, Courtin, Roudil and Vernet1987; Arnaud, Reference Arnaud, Cahen and Otte1990), laying the foundations for ideas of acculturation or horizontal cultural diffusion. The Mesolithic-Neolithic transition has become a well-established research topic of exceptional regional relevance (Oosterbeek, Reference Oosterbeek2001; Zilhão, Reference Zilhão2001; Carvalho, Reference Carvalho, Badal, Bernabeu and Marti2002; Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Pereira, Cascalheira, Marreiros, Gonçalves and Dias2013, Reference Bicho, Detry, Price and Cunha2015a, Reference Bicho, Cascalheira, Gonçalves, Umbelino, García Rivero and André2017; Guiry et al., Reference Guiry, Hillier, Boaventura, Silva, Oosterbeek and Tomé2016).

Regarding the defining characteristics of the Early Neolithic, a number of complications stem from considering south-western Iberia as a geographical cul-de-sac, to which successive waves of incoming groups may have arrived via different mechanisms and routes, and from different places. The current models of diffusion imply different pathways, points of passage, and rhythms of displacement (Fort, Reference Fort2015; Isern et al., Reference Isern, Zilhão, Fort and Ammerman2017; Pardo et al., Reference Pardo, García-Rivero and Bernabeu2019), and the question of movement by land or sea has a direct bearing on the weight ascribed to the Mediterranean cultural influence in the Atlantic regions (Zilhão, Reference Zilhão1993, Reference Zilhão, Ammerman and Biagi2003). The Mediterranean Early Neolithic has been linked in particular to the presence of Cardial impressed pottery, and occasionally to an earlier ceramic horizon related to the Ligurian-Provençal Impressa group (Bernabeu et al., Reference Bernabeu, Molina, Esquembre, Ortega, Boronat and Barbaza2009; Manen et al., Reference Manen, Convertini, Binder and Senepart2010). Although the latter is not currently known in the archaeological record of Portugal, several aspects of the ceramic definition of the Early Neolithic in this region are under scrutiny (Carvalho, Reference Carvalho2019): Cardial pottery as the only first-order material marker of the Early Neolithic has been questioned (Diniz, Reference Diniz, Borrell, Borrell, Bosch, Clop and Molist2012), and significant debate surrounds the status of Boquique pottery (Alday, Reference Alday2009; Alday & Moral, Reference Alday, Moral, Bernabeu, Rojo Guerra and Molina2011). Both issues are chronological and cultural in nature and, therefore, have bearing on the Early Neolithic periodization based on a two-stage model (Carvalho, Reference Carvalho2015; see also Martín-Socas et al., Reference Martín-Socas, Camalich Massieu, Caro Herrero and Rodríguez-Santos2018). Frameworks are also being reviewed in light of the current debate of the possible demographic and material influences from North Africa (e.g. Manen et al., Reference Manen, Marchand, Carvalho and Evin2007 vs Zilhão, Reference Zilhão2014) and the results of recent studies of ancient human DNA (Cruz, Reference Cruz2012; Gamba, Reference Gamba, Fernández, Tirado, Deguilloux, Pemonge and Utrilla2012; Szécsényi-Nagy et al., Reference Szécsényi-Nagy, Roth, Brandt, Rihuete-Herrada, Tejedor-Rodríguez and Held2017).

The Early Neolithic in the south-western regions of the Iberian Peninsula constitutes a complex and challenging field of research. The close succession of the Late Mesolithic, the early Early Neolithic and the late Early Neolithic within barely a few centuries is a test to both the theoretical frameworks and the archaeological record, with particular regard to the material identification of human groups of different provenance and cultural filiation. Several areas are crucial for the development of a more comprehensive model for the Atlantic regions: reliable site stratigraphies, radiocarbon dates for the first appearance of the archaeological elements associated with the Early Neolithic, and the precise and systematic characterization of pottery.

Here, we focus on the Muge region, an area of long-standing archaeological interest located in the estuarine environments of the Lower Tagus valley in central Portugal (Figure 1). At Cabeço da Amoreira, one of its best known Mesolithic shellmiddens, recent fieldwork has confirmed the existence of an Early Neolithic phase supported by consistent stratigraphic, chronological, and material evidence. The study of the pottery from this phase offers a unique opportunity to understand the complex processes unfolding during the second half of the sixth millennium cal bc, at the onset of the Early Neolithic in the southwestern-most region of mainland Europe.

Figure 1. Location of Cabeço da Amoreira, in the Muge region of the Lower Tagus valley, central Portugal. Left: location in Europe (Ministerio de Fomento, Gobierno de España, CC-BY 4.0 licence); centre: location in Portugal (ginkgomaps.com, CC-BY 3.0 licence); right: location of the shellmidden sites on the reconstructed palaeomargins of the Muge (1. Fonte do Padre Pedro; 2. Flor da Beira; 3. Cabeço da Arruda; 4. Moita do Sebastião; 5. Cabeço da Amoreira), Magos (6. Cova da Onça; 7. Monte dos Ossos; 8. Magos de Cima; 9. Cabeço da Barragem; 10 Cabeço dos Morros; 11. Magos de Baixo), and Fonte da Moça (12. Fonte da Moça I; 13. Fonte da Moça II) rivers.

The pottery analysis conducted on the materials recovered from the 2008–2014 excavations was designed as a detailed, site-specific study of the Early Neolithic pottery assemblage that may act as a reference for regional comparative studies in south-western Iberia. Our study focused on two main attributes: decoration and mineralogy, and aimed to explore the diversity of the assemblage as a measure of behavioural and cultural variability, to confirm the local production of pottery and to identify possible markers indicative of the provenance of incoming people and pots.

The Cabeço da Amoreira Shellmidden in the Early Neolithic

The Lower Tagus basin is characterized by recent sedimentary formations, created by the wandering of the riverbed in a large alluvial plain during the Lower and Middle Miocene (Pais, Reference Pais2004). On the left bank, marls and clays were deposited during the early Upper Miocene, followed by arkosic sands during the Pliocene. The shellmidden of Cabeço da Amoreira is sited on a terrace to the south of the river Muge, a left bank tributary of the Tagus (Figure 1), formed by sandy clays and clayey arenites (Zbyszewski & Veiga Ferreira, Reference Zbyszewski and Veiga Ferreira1968; for nomenclature, see Dias & Pais, Reference Dias and Pais2009).

The Tagus and its tributaries provided rich estuarine environments for human occupation, which intensified during the Holocene (e.g. Neves et al., Reference Neves, Rodrigues, Diniz and Diniz2008; Valente & Carvalho, Reference Valente, Carvalho, McCartan, Schulting, Warren and Woodman2009; Fernández & Jochim, Reference Fernández and Jochim2010; Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Umbelino, Detry and Pereira2010a). Since the discovery of the Muge shellmiddens in the nineteenth century, work at Cabeço da Amoreira has established the importance of the site for the study of the Mesolithic of western Europe. Recent fieldwork has been conducted since 2008 within three consecutive projects supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology. Previously unexplored areas of the site have been excavated, providing new stratigraphic and chronological information (Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Pereira, Cascalheira, Marreiros, Gonçalves and Dias2013).

The identification of Neolithic pottery in the upper layers of some Atlantic Mesolithic shellmiddens is not new (Obermaier, Reference Obermaier1916; Arias, Reference Arias and Moure1996) and it had been noted previously at Cabeço da Amoreira, Moita do Sebastião, Fonte do Padre Pedro, and Cabeço da Arruda in the Muge region (Mendes Corrêa, Reference Mendes Corrêa1934; Zbyszewski & Veiga Ferreira, Reference Zbyszewski and Veiga Ferreira1968; Veiga Ferreira, Reference Veiga Ferreira1974) (Figure 1). However, studies of this pottery have suffered from problems of stratigraphic provenance and cultural attribution. This question has been discussed in the similar context of the river Sado (Diniz, Reference Diniz, Gibaja and Cavalho2010; Diniz & Cubas, Reference Diniz, Cubas, Bicho, Detry, Price and Cunha2015) where pottery is also found within some shellmidden stratigraphies.

The Neolithic levels identified during the 2008–2010 excavations at Cabeço da Amoreira were defined materially by the presence of pottery, described as ‘small and eroded sherds’, and of lithic assemblages that differed from those of the Mesolithic (Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Cascalheira, Marreiros and Pereira2011). With reference to questions regarding the chronological and cultural filiation of the pottery identified at several Muge shellmiddens, the pottery was presented as Neolithic and the idea of Mesolithic pottery production and use was firmly dismissed (Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Dias, Pereira, Cascalheira, Marreieros, Pereira, Gonçalves, Gonçalves, Diniz and Sousa2015b: 637). Further work at the site confirmed an Early Neolithic phase with consistent stratigraphic and material evidence, and activity both on the mound itself and in its immediate surrounding area. This has been mentioned in several publications (since Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Pereira, Cascalheira, Marreiros, Pereira, Jesus, Gonçalves, Gibaja and Cavalho2010b), but the pottery record from the 2008–2014 field seasons has remained largely unpublished (Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Cascalheira, Marreiros and Pereira2011, Reference Bicho, Cascalheira, Gonçalves, Umbelino, García Rivero and André2017; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, García-Rivero, Cascalheira, Bicho, Pereira, Terradas and Bicho2017).

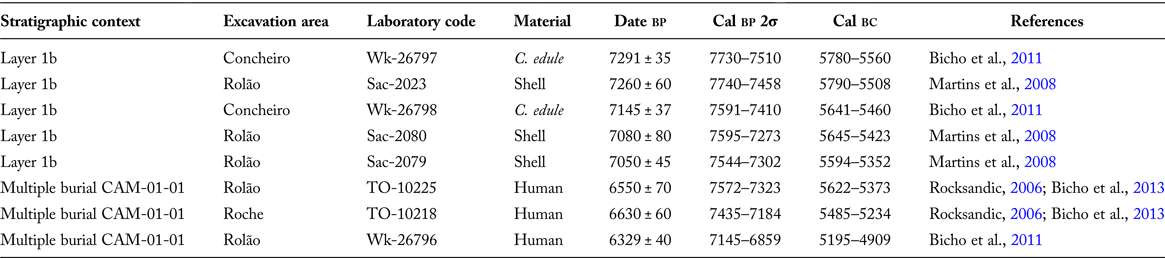

On the shellmidden, the scattered low-density presence of pottery has been interpreted as the result of small-scale activities leading to the inclusion of isolated pottery fragments in the upper shell layers (Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Dias, Pereira, Cascalheira, Marreieros, Pereira, Gonçalves, Gonçalves, Diniz and Sousa2015b). The spatial distribution of the sherds on the shellmidden is denser towards the edge of the mound, perhaps suggesting a degree of horizontal movement of the sherds, although the vertical stratigraphy appears not to have been disturbed. However, the patterns of fragmentation and distribution render it difficult to identify specific activities linked to the general usage of pottery. The elevation provided by the midden-cum-mound also contained Early Neolithic human burials, although pottery does not appear to have been included as a grave good. A group of three individuals buried in the same location over several centuries (CAM-01-01) is of particular interest. The earliest burial (TO-10225) is dated 5620–5370 cal bc (Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Cascalheira, Marreiros and Pereira2011) (see Table 1). Analysis of the tooth enamel of this individual for isotopic markers of diet and mobility indicated an entirely terrestrial diet and an exogenous origin, possibly in the Ossa Morena region of inland central Portugal (Price, Reference Price, Bicho, Detry, Price and Cunha2015), thus providing multiple forms of evidence for the presence of incoming people by, at least, 5350 cal bc (Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Pereira, Cascalheira, Marreiros, Gonçalves and Dias2013, Reference Bicho, Cascalheira, Gonçalves, Umbelino, García Rivero and André2017). The second burial (TO-10218) is close in date to the former: 5485–5235 cal bc, while the third (Wk-26796) has provided a later date: 5195–4910 cal bc, although still within the accepted Early Neolithic date range (Table 1).

Table 1. AMS dates (after Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Cascalheira, Gonçalves, Umbelino, García Rivero and André2017) for Shellmidden Layer 1b and the multiple burials CAM-01-01 at Cabeço da Amoreira. Calibration method: OxCal 4.2 (Bronk Ramsey, Reference Bronk Ramsey1995), with IntCal13 and Marine13 curves (Reimer et al., Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell and Bronk Ramsey2013). ΔR value of 140 ±40 (Martins et al., Reference Martins, Carvalho and Soares2008).

In the area immediately surrounding the shellmidden, Neolithic pottery has been identified in stratigraphy suggesting that the focus of occupation and daily activity may not have been the mound itself but its periphery (Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Cascalheira, Marreiros and Pereira2011, Reference Bicho, Pereira, Cascalheira, Marreiros, Gonçalves and Dias2013, Reference Bicho, Cascalheira, Gonçalves, Umbelino, García Rivero and André2017). The trench opened across the south-western slope of the midden has provided good stratigraphic information for the relationship between the formation of the mound and the depositional sequence of the surrounding area. Moreover, the sequence documented immediately off the mound supports two Early Neolithic phases characterized by distinctive pottery and lithics (Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Pereira, Cascalheira, Marreiros, Pereira, Jesus, Gonçalves, Gibaja and Cavalho2010b: 13).

Materials and Methods

Our work on the Cabeço da Amoreira pottery began with the new finds from the excavation areas opened between 2008 and 2014. The entire ceramic assemblage of just over 1000 sherds was studied (Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Cascalheira, Gonçalves, Umbelino, García Rivero and André2017: table 3; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, García-Rivero, Cascalheira, Bicho, Pereira, Terradas and Bicho2017). Attention then turned to the earliest pottery assemblage, defined on the grounds of strict stratigraphic and chronological criteria, from three areas: Shellmidden/Concheiro, a 12 × 12 m area located on the shellmidden itself; Trench/Vala, a 1 × 12 m-long trench opened across the south-western slope of the mound; and Area 1, a 4 × 4 m area located to the south-west of the mound, at the foot of the Trench area (Figure 2). Since the stratigraphic sequences from these three areas have numerical identifications for their units, a prefix (C: Concheiro; V: Vala; A: Area 1) was added to the identification of the layers and their materials.

Figure 2. Cabeço da Amoreira: old and new excavation areas (adapted from Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Cascalheira, Marreiros and Pereira2011: fig. 2) and western profile of the 2010 Trench/Vala area. Layer V5 corresponds to Layer C1, and Layer V3 to Layer C2.

A secure physical correspondence was established between Layer C1 of the Shellmidden sequence and Layer V5 of the Trench sequence, as well as between Layer C2 and Layer V3 (Figure 2). Moreover, a series of radiocarbon dates was obtained from Layer 1b of the Shellmidden sequence (an internal subdivision of Layer C1) and from the three human burials subsequently inserted in the mound. These AMS dates (Table 1) provide a consistent date of c. 5450–5050 cal bc for the Early Neolithic of Cabeço da Amoreira (Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Cascalheira, Gonçalves, Umbelino, García Rivero and André2017: 40). The Early Neolithic pottery assemblage in the Shellmidden and Trench areas was, therefore, defined as all the pottery contained in and under Layer C1 and Layer V5 (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, García-Rivero, Cascalheira, Bicho, Pereira, Terradas and Bicho2017). Area 1 also meets the same stratigraphic and chronological criteria, although it lacks a radiocarbon date or a direct physical correspondence with the previously mentioned stratigraphic layers. Horizons A2 and A2b of Area 1 have been published as two Early Neolithic phases (Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Pereira, Cascalheira, Marreiros, Pereira, Jesus, Gonçalves, Gibaja and Cavalho2010b), and pottery found in and under Horizon A2 is, therefore, adequate for our analysis.

The pottery remains are highly fragmented and fragmentary, and formal and decorated sherds are scarce, severely limiting the possibilities of exploring relationships between vessel form, function, and style. An approach combining visual examination and thin section petrography, concentrating on decorative techniques and the identification of mineral inclusions, was therefore considered an effective way of obtaining an informative body of data.

A two-fold procedure was followed. A visual examination was first carried out, gathering valuable information on the general physical characteristics of the pottery from the Early Neolithic layers of the Shellmidden and Trench excavation areas (n = 201). Attributes such as fragmentation, wall thickness, surface treatment, firing conditions, colour, and main mineralogical group are summarized in Table 2 (after Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, García-Rivero, Cascalheira, Bicho, Pereira, Terradas and Bicho2017). A petrographic analysis was then undertaken on a representative subsample of forty-seven sherds from Vala, Concheiro, and Area 1 (Table 3).

Table 2. Main characteristics of the Cabeço da Amoreira Early Neolithic pottery, based on the hand-specimen analysis of materials from the Shellmidden and Trench excavation areas, 2008–2014 (n = 201) (after Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, García-Rivero, Cascalheira, Bicho, Pereira, Terradas and Bicho2017).

Table 3. List of samples for thin section petrography, by excavation area and stratigraphic layer. Number of pottery records after Bicho et al. (Reference Bicho, Cascalheira, Gonçalves, Umbelino, García Rivero and André2017: table 3).

Twenty-eight samples were selected from the Trench/Vala assemblage. These include all the decorated fragments (seven decorated rim and body sherds), two plain rim sherds and nineteen plain body sherds representative of the fabric diversity identified in the visual examination. A further twelve undecorated samples were selected from the Shellmidden/Concheiro excavation area. Finally, all but one of the decorated pottery fragments from Area 1 were sampled (five decorated rim sherds and two decorated body sherds). This area has the most diverse decorative repertoire documented so far at the site, and it is significant that the largest number of decorated fragments comes from Horizon A2b, the earliest of the two proposed Early Neolithic phases in the sequence (Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Pereira, Cascalheira, Marreiros, Pereira, Jesus, Gonçalves, Gibaja and Cavalho2010b).

The petrographic analysis presented in this study focuses specifically on the mineralogy of the samples. Indeed, simple mineralogy enabled a range of observations with potentially high-impact implications for our region and period. The criteria for the identification of minerals in thin section are well-established, including the optical properties of mineral families and species, their possible alteration, the association of minerals, and the petrology of rocks (e.g., MacKenzie & Guilford, Reference MacKenzie and Guilford1980; Delvigne, Reference Delvigne1998; Melgarejo, Reference Melgarejo2003; Haldar & Tisljar, Reference Haldar and Tisljar2014). For each sample, the presence and relative frequency of each mineral inclusion type was presented. Textural attributes habitually included in fabric analyses (size, shape, sorting; Quinn, Reference Quinn2013; Whitbread, Reference Whitbread and Hunt2017) are not considered here. The thin sections were analysed in the Department of Prehistory and Archaeology at the University of Seville using a Nikon Eclipse E200 petrographic microscope coupled with a digital camera and image processing software managed through NSIC-Elements.

Results

The decorated pottery

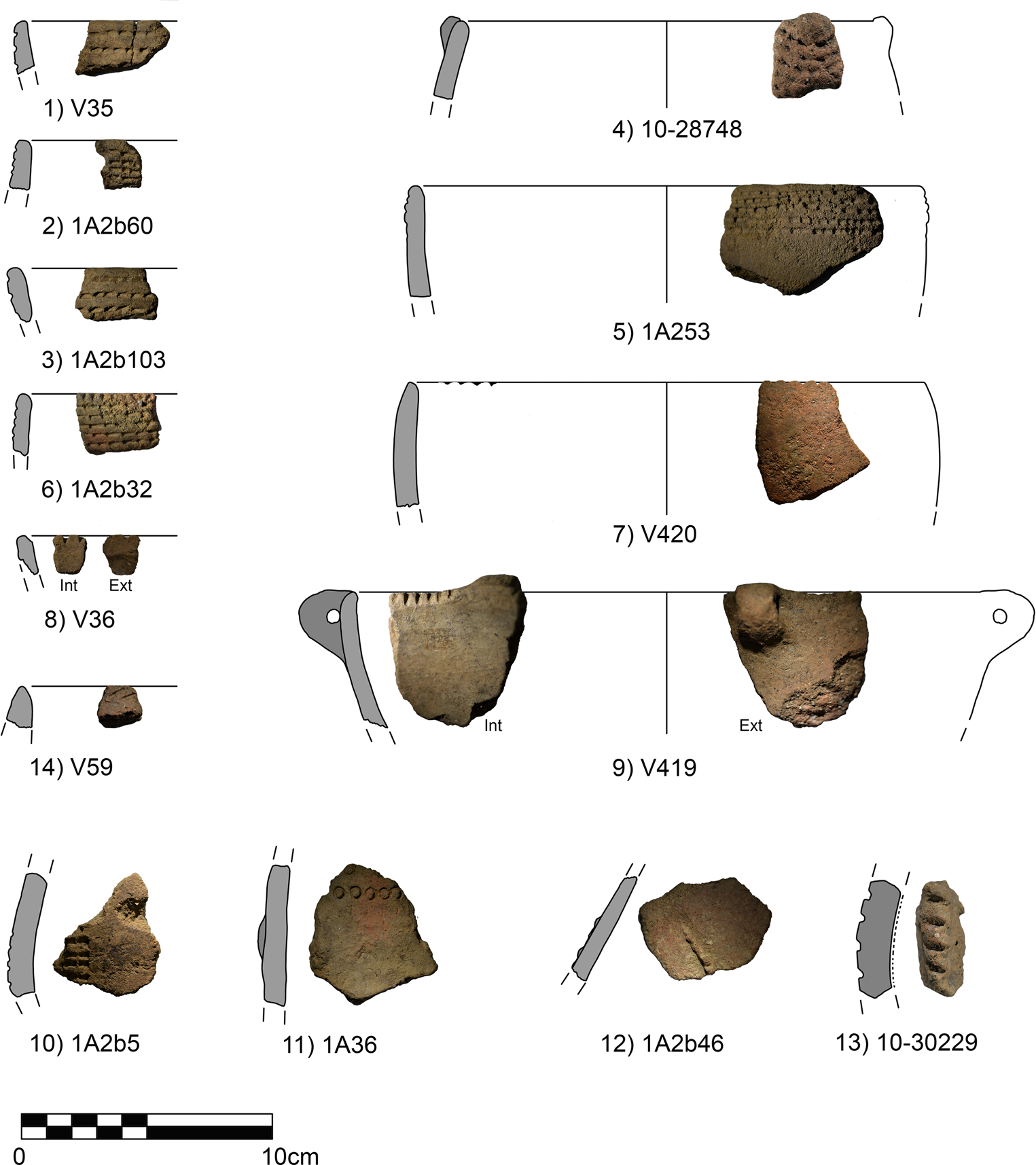

The decorated pottery assemblage currently known from the excavation of Shellmidden, Trench, and Area 1 consists of nineteen decorated fragments (Table 4). The low representation of decorated fragments at Cabeço da Amoreira may in part be explained by the restriction of decoration to the upper body and rim (Figure 3), thus leading to a larger proportion of plain sherds per vessel, or more generally by the scarcity of decorated vessels.

Table 4. The 2008–2014 Cabeço da Amoreira decorated pottery, by excavation area and stratigraphic layer. App: appendage; Bq: Boquique; Imp: impressed; Inc: incised. n/a: not analysed. n/i: not illustrated.

Figure 3. Cabeço da Amoreira Early Neolithic decorated pottery. 1–5) Boquique; 6) Boquique and impressed rim; 7–9) impressed rims; 10–11) other impressed techniques; 12–13) plastic techniques; 14) incised.

The predominance of Boquique is a most noteworthy feature of the decorated assemblage. Also, the absence of decorated pottery below Layer V3 of the Trench and Layer C1 of the Shellmidden may be consistent with an early suggestion by Russell Cortez (Reference Russell Cortez1953: 88) of an initial undecorated pottery phase, although this has not been observed in Area 1. The distribution by decorative technique is as follows:

Boquique (ten cases). The rows of characteristic impressions, known in the Iberian Neolithic as boquique, run in horizontal lines parallel to the rim (Figure 3, nos. 1–3 and 5). In one case, they curve around a small rounded appendage (Figure 3, no. 4). Typologically, rim and oriented body sherds indicate an association of this decorative technique with bowls, and more rarely with closed forms. In one case, a single preserved line of Boquique is combined with a parallel incised line (not illustrated).

Boquique and impressed rim (one case). A band of five rows of Boquique impressions is combined with an impressed or dentated rim (Figure 3, no. 6).

Impressed or ‘dentated’ rims (three cases). Impressed or dentated rims are documented alone on three fragments (Figure 3, nos. 7–9). The impressions vary between U-shaped and V-shaped, indicating diverse tool profiles.

Other impressed decoration (two cases). The fragment illustrated in Figure 3 no. 11 bears discrete, clear, and evenly spaced circular impressions, made with a hollow tubular instrument, and forming a horizontal band. The fragment shown in Figure 3 no. 10 is possibly shell impressed.

Plastic modelled/applied (two cases). A body sherd has a slim raised modelled ridge (Figure 3, no. 12) and another sherd is in fact a thick applied cordon, detached from the body (Figure 3, no. 13), with deep, slightly oblique U-shaped impressions.

Incised decoration (one case). Only one rim sherd displays a single row of discrete oblique incisions (Figure 3, no.14).

Mineralogical Characteristics

Based on mineralogical characteristics, six fabric groups emerged from the petrographic analysis (Table 5, Figure 4): Groups 1 to 3 are quartzofeldspathic and predominant; Groups 4 and 5 are igneous and distinctive; Group 6 are rare and, possibly, an unusual choice for pottery manufacturing.

Table 5. Mineralogical characteristics and groups. Texture: VF: very fine; F: fine; M: medium; Ir: irregular. Frequency: Rare; Sp: sparse; Mod: moderate; C: common; VC: very common; A: abundant; VA: very abundant. X: majority; x: minority; (x): rare/isolated grains. Standard mineral abbreviations: Qz: quartz; Kfs: K-feldspars; Pl: plagioclase; Ms: muscovite; Bt: biotite; Opq: opaque minerals. Decoration: Bq: boquique; Imp: impressed; Inc: incised.

Figure 4. Fabric groups based on mineralogical characteristics: hand-specimens (scale 2 mm) and thin section under cross polarized light (20×) of representative samples: Group 1 Sample C2110, Group 2 Sample V418, Group 3 Sample C2118, Group 4 Sample V317, Group 5 Sample V417, Group 6 Sample V213.

Group 1 Quartz + K-feldspar

Group 1 contains only quartz and K-feldspar, the main components of the arkosic sands of the Lower Tagus valley, described as yellow to red/brown and fine/medium to coarse in grain, with low kaolinite and illite contents (Zbyszewski & Veiga Ferreira, Reference Zbyszewski and Veiga Ferreira1968; Pais, Reference Pais2004). Muscovite mica and plagioclase feldspar are absent. The presence of mud/clay pellets is significant in this group and may be indicative of clay formation conditions. Fine-grained sedimentary rock fragments are occasionally present as isolated rounded grains.

Group 2 Quartz + K-feldspar + muscovite mica in the fine fraction of the clay

This group, similar to Group 1, contains muscovite mica as a fine fraction inclusion. Mud/clay pellets and fine-grained rock inclusions are present in fewer samples than in Group 1. These characteristics may be indicative of a similar geological source, with slightly different depositional conditions and sedimentary contributions, although the geographic proximity between Groups 1 and 2 is difficult to establish.

Group 3 Quartz + K-feldspar + plagioclase + muscovite

The micromorphological analysis of sediments from the Shellmidden sequence of Cabeço da Amoreira identified the predominant mineral fraction as ‘medium to coarse quartz sand, to a lesser extent feldspar (microcline and plagioclase), and few silt-sized mica (muscovite)’ (Aldeias & Bicho, Reference Aldeias and Bicho2016: table 1), analogous to the sandy clay and clayey arenite substrate on which the mound is located (Zbyszewski & Veiga Ferreira, Reference Zbyszewski and Veiga Ferreira1968).

Group 3 is the closest match to this site-specific mineralogical description. Mud/clay pellets and fine-grained sedimentary rock inclusions display a similar frequency as in Group 2. The presence of plagioclase indicates a mineralogical association that differs from that of Groups 1 and 2. Group 3 displays a variant (3*) represented by only two samples in which mica was not identified.

Group 4 Igneous rock fragments and weathered biotite mica

Group 4 is characterized by igneous rock fragments and weathered biotite mica, but also includes individual grains of quartz and K-feldspar, and plagioclase in some samples. Muscovite mica is not present. The igneous rock fragments typically display the association of quartz with K-feldspar, rarely with plagioclase. If derived from granite, the complete loss of micas (muscovite and fresh biotite) and absence of ferromagnesian minerals are noteworthy.

Weathered biotite mica is the principal distinguishing characteristic of this group. Visually, it was identified as golden-red mica in frequencies varying from sparse flecks to a major inclusion. Petrographically, it corresponds to the type described by Delvigne (Reference Delvigne1998: reference slides 172–73) as a ‘meso-alteromorph after biotite’ characterized by the occurrence of lenticular intramineral pores, and more specifically as a ‘phylloporo-alteromorph’ considering both geometric and internal microtextural criteria. It is most probably source-specific, resulting from a particular geological process. Indeed, the mineralogy of Group 4 does not belong to the Neogene formations of the Lower Tagus valley and Group 4 pots must be interpreted as imports to the site. Moreover, three of the seven analysed Boquique fragments belong to this mineralogical group, and, significantly, Group 4 is not (in our sample) associated with any other decorative technique.

Group 5 Igneous rock fragments, including granite, and no weathered biotite

This group contains inclusions from an igneous source and includes granite rock fragments. In contrast to Group 4, weathered biotite is absent, while fresh biotite is present only in rock fragments. Again, the absence of ferromagnesian minerals, with the rare exception of single crystals of amphibole and pyroxene in fabrics also containing plagioclase, can be noted.

Geologically, Group 5 provides a probable reference to the granitic areas of inland central Portugal, and to geological formations belonging to the Ossa Morena and Central Iberian zones. In one case, grog is identified alongside granite, thus providing a unique technological and geographic marker in a single sample.

Group 6 Pure clay

Group 6 includes only two samples. Their distinctive texture is justified by the (near) absence of sizeable mineral inclusions. At present it is not clear whether this fabric type constitutes evidence of raw material processing. The suitability of this material for pottery production is questionable, given the potential difficulties of shaping, drying, and firing. However, one of the analysed samples belongs to a pot with a distinctive impressed decoration from the lower layer of Area 1. The unusual choice of raw material and the stratigraphic position of this fragment may be connected.

Based on mineralogy, the assemblage includes both regionally produced and exogenous pottery, since the earliest appearance of pottery at the site. The predominant quartzofeldspathic mineralogies (Groups 1, 2, and 3) are consistent with the sedimentary geology of the Lower Tagus valley, and Group 3, in particular, is a good match for the site. Groups 4 and 5, by contrast, contain weathered biotite and granite that are indicative of geological origins outside the Neogene Basin. In addition, the identification of grog in a granite-bearing fabric is a specific technological trait not observed in the regional sandy fabrics.

If Groups 1, 2, and 3 are consistent with the regional geology and Groups 4 and 5 are not (Group 6 must be treated with caution), and Horizon 2b of Area 1 is representative of the earliest consistent Early Neolithic decorated pottery phase at Cabeço da Amoreira, several conclusions can be drawn from the mineralogical analysis combined with the decorative techniques and stratigraphy (Table 6):

– The earliest pottery at the site was local (association with Groups 2 and 3) and non-local (association with Groups 4 and 5), as defined by mineralogy. The first pottery users at the site were, therefore, pottery producers, but pots were also brought to the site from other sources.

– Boquique, impressed, and incised decorative techniques appear to have been introduced to the site from a different region of origin (association with Groups 4 and 5). Boquique decoration, in particular, has a strong link to the weathered mica fabric group (Group 4).

– This decorative technique and style were, however, rapidly transferred to pots made in local quartzofeldspathic fabrics (association with Groups 1, 2, and 3). Moreover, it was combined with impressed or dentated rims, exclusively associated with Groups 1 and 2.

Table 6. Correlation between mineralogical group, decorative technique, and stratigraphic position. Decoration: Bq: boquique; Imp: impressed; Inc: incised.

Discussion and Conclusions

The analysis of the pottery from Cabeço da Amoreira has potentially far-reaching implications for the interpretation of the large-scale processes that took place during the sixth millennium bc in the Atlantic regions of the Iberian Peninsula. Given the primary definition of the site as a Mesolithic shellmidden, the presence of pottery in stratigraphy and from an early date is particularly significant.

The first pottery users at Cabeço da Amoreira were also pottery makers, as indicated by the predominance of mineral associations consistent with the regional and local geological setting. Moreover, the Early Neolithic inhabitants appear to have arrived at the site with a well-defined technological tradition of pottery production, uniform in its methods and products, and suggestive of a close-knit cultural group.

However, Boquique, impressed, and incised decorated pots were also brought to the site from other places of origin, as indicated by the identification of distinctive mineral inclusions in the ceramic pastes. Three of the seven analysed Boquique fragments belong to the exogenous Group 4. This characteristic style was rapidly transferred to locally made pots, containing Tagus Valley sands, and was also combined with impressed or dentated rims that may have been a typical decorative style in the region, associated exclusively with local clay sources at Cabeço da Amoreira (Groups 1 and 2) and with close formal parallels at Cortiçóis (Benfica do Ribatejo) (Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Carvalho and Gibaja2013) and Moita do Sebastião (Cardoso, Reference Cardoso2015).

At Cabeço da Amoreira, Boquique decoration accounts for over half of the decorated assemblage. This is a significantly high proportion, considering that this decorative technique is not usually documented as a predominant type in the Iberian Peninsula (Alday & Moral, Reference Alday, Moral, Bernabeu, Rojo Guerra and Molina2011), and it may point to the strong cultural and material identity of the Early Neolithic occupants of the site. Indeed, the identification of Boquique as the main decorative style at Cabeço da Amoreira requires consideration of the possible cultural filiation of the Early Neolithic of the Muge valley in relation to the coastal, inland, and Mediterranean Neolithic groups and/or cultural influences that were active in the south-western Iberian Peninsula in the second half of the sixth millennium cal bc.

Based on the chronological evidence for the Muge region, previous work suggested a first phase of contemporaneity between the Mesolithic populations and the arrival of the first Neolithic groups to Portuguese Estremadura, and a second phase in which the Early Neolithic communities began to use the shellmiddens, after their abandonment by the last Mesolithic groups. This second phase has been assigned a date range, based on available radiocarbon results, of c. 7400–7000 cal bp or 5450–5050 cal bc (Bicho et al., Reference Bicho, Cascalheira, Gonçalves, Umbelino, García Rivero and André2017: 40), spanning the accepted regional range of the Early Neolithic, which may now be characterized at Cabeço da Amoreira as a predominantly Boquique horizon.

A large-scale study in the Iberian Peninsula (Alday, Reference Alday2009) suggested that Boquique and Cardial may appear independently or together at the same sites and within the same date ranges. Based on an extensive body of radiocarbon dates, the initial development of Boquique has been suggested in the mid-sixth millennium cal bc in the central and western regions of the Iberian Peninsula, and its identification has been defended as a first-order marker of the onset of the Early Neolithic (Alday & Moral, Reference Alday, Moral, Bernabeu, Rojo Guerra and Molina2011). However, this proposal does not provide a satisfactory explanation for the differential distribution of Cardial and Boquique pottery. For instance, the well-known Gruta do Caldeirão has a Cardial horizon dated to c. 5480–5100 cal bc (at 2σ; Barnett, Reference Barnett1987; Zilhão, Reference Zilhão1993, Reference Zilhão2001; Carvalho, Reference Carvalho, Bernabeu, Rojo Guerra and Molina2011) but no Boquique pottery has been recorded. The implicit hypothesis, if, as argued by Alday and Moral, the two styles were coeval, is that sites may have been used by groups with different ancestry or origins. By contrast, other authors maintain the contextualization of the Boquique style towards the end of the sixth millennium, and generally not earlier than 5100 cal bc, in a second phase of the Early Neolithic known variously as Epicardial or Evolved (Carvalho, Reference Carvalho, Bernabeu, Rojo Guerra and Molina2011, Reference Carvalho2015). This is the case, for instance, at the rock shelter of Pena d'Água (Torres Novas), where Cardial and Boquique ceramics are found sequentially: Boquique is absent at the very base of the sequence (Eb base), followed by Cardial and Boquique in equal proportions in the upper division of the same layer (Eb), while Cardial is absent and a lower proportion of Boquique is present in the most recent Early Neolithic phase (Ea) (Carvalho, Reference Carvalho and Bonet2016, Reference Carvalho2019). At Galeria da Cisterna in the Almonda karst system, Boquique pottery is attributed to the Epicardial phase (Zilhão, Reference Zilhão2001, Reference Zilhão, Barbaza, Coularou and Courtin2009) dated after c. 5000 cal bc (Zilhão & Carvalho, Reference Zilhão, Carvalho, Bernabeu, Rojo Guerra and Molina2011: 254), and in the granitic interior region of the Alentejo, the Epicardial open air site of Valada do Mato (Évora), with minor amounts of Cardial and Boquique pottery, is dated to the transition from the sixth to the fifth millennium cal bc (Diniz, Reference Diniz2007, Reference Diniz, Bernabeu, Rojo Guerra and Molina2011, Reference Diniz, Borrell, Borrell, Bosch, Clop and Molist2012).

The dates of the Cabeço da Amoreira Boquique assemblage may therefore be earlier than expected within the regional context and it will be necessary to follow up the characterization of pottery at neighbouring sites (<5 km distance). Special mention must be made of the open air sites of Casas Velhas do Coelheiro (Salvatierra de Magos) (Andrade et al., Reference Andrade, Neves, Lopes, Bicho, Detry, Price and Cunha2015; Neves et al., Reference Neves, Diniz and Lopes2015) and especially of Cortiçóis (Benfica do Ribatejo) (Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Carvalho and Gibaja2013), located to the north of the river Muge and providing a close comparative context for the Early Neolithic pottery assemblage of Cabeço da Amoreira.

Interestingly, the terms Epicardial or Evolved Early Neolithic imply an assumption of continuity, whereas the appearance of a characteristic decorative style with a wide geographic distribution, as is the case of the so-called ‘Boquique domain’, may reasonably be considered suggestive of the arrival of a new wave of incoming populations with a different pottery tradition. Regarding the possible geographic origin of the Boquique pottery documented at Cabeço da Amoreira, the identification of a visually distinctive mica-rich fabric, with a particularly strong association to this decorative style, is noteworthy, as is granite, identified in a small number of other samples. The mineralogical evidence provided by Groups 4 and 5, therefore, suggests a geological and geographic reference to the granitic domains of central Portugal. The observation of grog temper in a single granite-bearing sample may also indicate a specific technological practice not known (to date) in the local sandy fabrics. Additional supporting evidence comes from the individual burial Wk-35718, dated to c. 5350 cal bc, for which strontium isotope results indicate an exogenous origin in the Ossa Morena or Central Iberian zones (Price, Reference Price, Bicho, Detry, Price and Cunha2015: 232–33). Potter's clay and human bones, therefore, provide converging evidence, apparently contrary to the maritime pioneer colonization model, although this proposal warrants careful further assessment.

The mobility of people, ideas, and products is, arguably, one of the defining features of the process of Neolithization, envisaged as the result of demic and/or cultural diffusion. Decorative traits on pottery have been used extensively for classification and cultural assignation, while technological analyses have attracted less attention, despite their proven potential. Recently, for instance, Masucci and Carvalho (Reference Masucci and Carvalho2016) have identified the bidirectional long-distance transport of Cardial pottery in the second half of the sixth millennium bc between the Algarve and Estremadura in Portugal. In the case of Cabeço da Amoreira, the granitic rock fragments and mineral associations point inland towards the Alentejo and provide a solid lead for future work.

By carefully defining the material under study, based on secure site stratigraphy and dates, we have reached a better understanding of the Cabeço da Amoreira Early Neolithic pottery assemblage, and have also strengthened the contribution of the pottery analysis to the broader questions surrounding the nature of the site and its occupants. Within the context of the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition and the Early Neolithic in south-western Europe, the new results made available from Cabeço da Amoreira are certainly impactful for the region and period under study. Planned future work will further expand and test the data and ideas presented here.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the project ‘High-resolution chronology and cultural evolution in the South of the Iberian Peninsula (7000–4000 cal bc): A multiscalar approach’, funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (grant PGC2018-096943-A-C22). Fieldwork at Cabeço da Amoreira has been supported by three consecutive research grants from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (grants PTDC/HAH/64185/2006, PTDC/HIS-ARQ/112156/2009 and ALG-01-0145-FEDER-29680). The preparation of thin sections was financed by the second of these projects.