1 Introduction

Coherent flow structures are present in most turbulent flows. Coherent structures associated with vortex shedding, in particular, are clearly present in turbulent wakes. One can expect these structures to have some impact on a two-point energy balance which takes into account both interscale and interspace energy transfers. Such an energy balance that can be applied to turbulent flows which are not necessarily homogeneous and isotropic has already been used by various authors to analyse turbulent flows, starting with Marati, Casciola & Piva (Reference Marati, Casciola and Piva2004) who applied it to turbulent channel flow. This energy balance, first derived by Hill (Reference Hill2002b) (but see also Duchon & Robert (Reference Duchon and Robert2000)), is sometimes referred to as the Kármán–Howarth–Monin–Hill (KHMH) equation because it fully generalises the Kármán–Howarth–Monin equation (see Frisch Reference Frisch1995) which is limited to homogeneous and to periodic turbulence. To our knowledge, there has been, to date, only one study of such an energy balance in a boundary free turbulent shear flow which takes account of coherent structures. This is the study of Thiesset, Danaila & Antonia (Reference Thiesset, Danaila and Antonia2014) who derived a KHMH equation written for a triple decomposition, where the coherent quasi-periodic part of the fluctuating velocity field is explicitly treated in the analysis as distinct from the stochastic turbulent fluctuations. Thiesset et al. (Reference Thiesset, Danaila and Antonia2014) applied their two-point equation to a turbulent wake of a cylinder and concentrated attention at downstream distances between  $10d$ and

$10d$ and  $40d$, where

$40d$, where  $d$ is the diameter of the cylinder. They found that the coherent structures impose a forcing on the stochastic fluctuations and proposed an analytical model which describes the energy content of such structures in scale space.

$d$ is the diameter of the cylinder. They found that the coherent structures impose a forcing on the stochastic fluctuations and proposed an analytical model which describes the energy content of such structures in scale space.

The one other study of the KHMH equation in a planar turbulent wake is that of Alves Portela, Papadakis & Vassilicos (Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2017) who looked at interscale and interspace exchanges in the near wake of a square prism of side width  $d$ but did not consider the effects of vortex shedding coherent structures. They found that

$d$ but did not consider the effects of vortex shedding coherent structures. They found that  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{a}$, the rate at which turbulent energy is transferred across scales when averaged over orientations in the plane of the mean-flow (plane normal to coordinate

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{a}$, the rate at which turbulent energy is transferred across scales when averaged over orientations in the plane of the mean-flow (plane normal to coordinate  $x_{3}$), is roughly constant, and in fact close to the turbulence dissipation rate

$x_{3}$), is roughly constant, and in fact close to the turbulence dissipation rate  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}$, over a wide range of scales at a distance

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}$, over a wide range of scales at a distance  $8d$ from the square prism. Their direct numerical simulation (DNS) showed that this is also true, albeit over a much reduced range of length scales, at a distance

$8d$ from the square prism. Their direct numerical simulation (DNS) showed that this is also true, albeit over a much reduced range of length scales, at a distance  $2d$ from the square prism. Their KHMH analysis made it clear that this Kolmogorov-sounding constancy of

$2d$ from the square prism. Their KHMH analysis made it clear that this Kolmogorov-sounding constancy of  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{a}$ cannot be the result of a Kolmogorov equilibrium cascade given that the near-field region of the flow where it is observed is very inhomogeneous, anisotropic and out of equilibrium. One is therefore naturally faced with the question of the role of the coherent structures in establishing

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{a}$ cannot be the result of a Kolmogorov equilibrium cascade given that the near-field region of the flow where it is observed is very inhomogeneous, anisotropic and out of equilibrium. One is therefore naturally faced with the question of the role of the coherent structures in establishing  $-\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{a}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}\approx 1$ and the extent to which this approximate constancy is due to the stochastic component of the turbulent fluctuations. We also attempt to address the direct contribution of spatial inhomogeneity to the behaviour of

$-\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{a}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}\approx 1$ and the extent to which this approximate constancy is due to the stochastic component of the turbulent fluctuations. We also attempt to address the direct contribution of spatial inhomogeneity to the behaviour of  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{a}$.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{a}$.

In this paper we use the triple decomposition KHMH equations of Thiesset et al. (Reference Thiesset, Danaila and Antonia2014) which we slightly generalise to include mean flow velocity differences. We analyse the data obtained by Alves Portela et al. (Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2017) from their DNS of the turbulent planar wake of a square prism of side length  $d$. The inlet free-stream velocity

$d$. The inlet free-stream velocity  $U_{\infty }$ in this DNS is such that

$U_{\infty }$ in this DNS is such that  $U_{\infty }d/\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}=3900$ where

$U_{\infty }d/\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}=3900$ where  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}$ is the fluid’s kinematic viscosity. We refer to Alves Portela et al. (Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2017) for details of this DNS.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}$ is the fluid’s kinematic viscosity. We refer to Alves Portela et al. (Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2017) for details of this DNS.

In § 2 we explain how the triple decomposition is carried out and how we extract from the time-varying fields of velocity and pressure a contribution associated with the vortex shedding. In § 3 we detail the scale-by-scale KHMH budgets that we use in this paper to explore combined interscale and interspace transfers in the near wake of a square prism and in § 4 we report on the various terms in our KHMH budgets in an orientation-averaged sense. Section 5 presents our results on interscale energy transfers and scale-space fluxes and we conclude in § 6.

2 Triply decomposed velocity field

The Reynolds decomposition distinguishes between the mean field and the fluctuating field. When the flow exhibits a well-defined non-stochastic (e.g. periodic) flow feature, one can further decompose the fluctuating field into a coherent field and a stochastic field (Hussain & Reynolds Reference Hussain and Reynolds1970; Reynolds & Hussain Reference Reynolds and Hussain1972). The velocity field is therefore the sum of three fields:  $\boldsymbol{u}_{\boldsymbol{f}\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{l}\boldsymbol{l}}=\boldsymbol{U}+\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}+\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }$, where

$\boldsymbol{u}_{\boldsymbol{f}\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{l}\boldsymbol{l}}=\boldsymbol{U}+\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}+\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }$, where  $\boldsymbol{U}$ is the mean velocity field obtained by time-averaging

$\boldsymbol{U}$ is the mean velocity field obtained by time-averaging  $\boldsymbol{u}_{\boldsymbol{f}\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{l}\boldsymbol{l}}$, and where

$\boldsymbol{u}_{\boldsymbol{f}\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{l}\boldsymbol{l}}$, and where  $\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ and

$\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ and  $\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }$ are the coherent and stochastic parts, respectively, of the fluctuating velocity field. The coherent fluctuating velocity

$\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }$ are the coherent and stochastic parts, respectively, of the fluctuating velocity field. The coherent fluctuating velocity  $\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ is obtained by phase-averaging

$\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ is obtained by phase-averaging  $\boldsymbol{u}_{\boldsymbol{f}\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{l}\boldsymbol{l}}-\boldsymbol{U}$ and the stochastic fluctuating velocity is the remainder and is obtained from

$\boldsymbol{u}_{\boldsymbol{f}\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{l}\boldsymbol{l}}-\boldsymbol{U}$ and the stochastic fluctuating velocity is the remainder and is obtained from  $\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }=\boldsymbol{u}_{\boldsymbol{f}\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{l}\boldsymbol{l}}-\boldsymbol{U}-\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$. If

$\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }=\boldsymbol{u}_{\boldsymbol{f}\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{l}\boldsymbol{l}}-\boldsymbol{U}-\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$. If  $\boldsymbol{u}_{\boldsymbol{f}\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{l}\boldsymbol{l}}$ is incompressible,

$\boldsymbol{u}_{\boldsymbol{f}\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{l}\boldsymbol{l}}$ is incompressible,  $\boldsymbol{U}$,

$\boldsymbol{U}$,  $\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ and

$\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ and  $\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }$ are incompressible too. With similar notation one also decomposes the pressure field,

$\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }$ are incompressible too. With similar notation one also decomposes the pressure field,  $p=P+\tilde{p}+p^{\prime }$. In the present work which is concerned with the planar wake of a square prism, both time- and phase-averaging operations also involve averaging in the spanwise direction, i.e. in the direction

$p=P+\tilde{p}+p^{\prime }$. In the present work which is concerned with the planar wake of a square prism, both time- and phase-averaging operations also involve averaging in the spanwise direction, i.e. in the direction  $x_{3}$ which is normal to the plane of the average wake flow. Fluid velocities and spatial coordinates in the streamwise direction are denoted by

$x_{3}$ which is normal to the plane of the average wake flow. Fluid velocities and spatial coordinates in the streamwise direction are denoted by  $U_{1}$,

$U_{1}$,  $\tilde{u} _{1}$,

$\tilde{u} _{1}$,  $u_{1}^{\prime }$ and

$u_{1}^{\prime }$ and  $x_{1}$, respectively; in the cross-stream direction they are

$x_{1}$, respectively; in the cross-stream direction they are  $U_{2}$,

$U_{2}$,  $\tilde{u} _{2}$,

$\tilde{u} _{2}$,  $u_{2}^{\prime }$ and

$u_{2}^{\prime }$ and  $x_{2}$. The spanwise fluid velocity components are

$x_{2}$. The spanwise fluid velocity components are  $U_{3}$,

$U_{3}$,  $\tilde{u} _{3}$,

$\tilde{u} _{3}$,  $u_{3}^{\prime }$.

$u_{3}^{\prime }$.

The definitions of  $\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ and

$\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ and  $\tilde{p}$ require a reference phase. One can obtain a reference phase from a pressure tap on the cylinder (see e.g. Braza, Perrin & Hoarau Reference Braza, Perrin and Hoarau2006) or from the fluctuating velocity signal, either from within the turbulent flow after appropriately filtering (see e.g. Thiesset et al. Reference Thiesset, Danaila and Antonia2014) or from the outside of the turbulent core (see e.g. Davies Reference Davies1976). Wlezien & Way (Reference Wlezien and Way1979) provide an extensive comparison of different methods with focus on experimental techniques.

$\tilde{p}$ require a reference phase. One can obtain a reference phase from a pressure tap on the cylinder (see e.g. Braza, Perrin & Hoarau Reference Braza, Perrin and Hoarau2006) or from the fluctuating velocity signal, either from within the turbulent flow after appropriately filtering (see e.g. Thiesset et al. Reference Thiesset, Danaila and Antonia2014) or from the outside of the turbulent core (see e.g. Davies Reference Davies1976). Wlezien & Way (Reference Wlezien and Way1979) provide an extensive comparison of different methods with focus on experimental techniques.

In the present analysis, the phase angle  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ used to compute phase averages is extracted from the Hilbert transform of the lift coefficient

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ used to compute phase averages is extracted from the Hilbert transform of the lift coefficient  $C_{L}$ (see Feldman (Reference Feldman2011) for details on the Hilbert transform). This choice follows naturally from the fact that the lift on the square prism in our flow closely follows a sinusoid in time.

$C_{L}$ (see Feldman (Reference Feldman2011) for details on the Hilbert transform). This choice follows naturally from the fact that the lift on the square prism in our flow closely follows a sinusoid in time.

The data being discrete in time,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ was binned into

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ was binned into  $32$ groups. A smaller bin size would have improved phase resolution but would have reduced statistical convergence (as fewer samples would have fallen within each bin). Thus, each time instant is associated with a value

$32$ groups. A smaller bin size would have improved phase resolution but would have reduced statistical convergence (as fewer samples would have fallen within each bin). Thus, each time instant is associated with a value  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=-\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}+n(2\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}/32)$ where

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=-\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}+n(2\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}/32)$ where  $0<n<31$. The resulting phase-averaged lift and drag coefficients are plotted in figure 1 versus the phase angle

$0<n<31$. The resulting phase-averaged lift and drag coefficients are plotted in figure 1 versus the phase angle  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$, where

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$, where  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=0$ has been chosen such that

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=0$ has been chosen such that  $\tilde{C}_{L}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=0)=0$.

$\tilde{C}_{L}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=0)=0$.

Figure 1. Evolution of phase-averaged lift and drag coefficients  $\tilde{C}_{L}$ and

$\tilde{C}_{L}$ and  $\tilde{C}_{D}$ along the normalised phase

$\tilde{C}_{D}$ along the normalised phase  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}/\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}$.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}/\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}$.

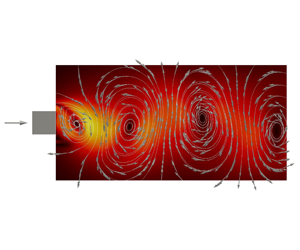

The phase-averaged velocity field  $\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ is shown in figure 2 for four different values of

$\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ is shown in figure 2 for four different values of  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$:

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$:  $0$,

$0$,  $\frac{1}{4}\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}$,

$\frac{1}{4}\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}$,  $\frac{1}{2}\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}$ and

$\frac{1}{2}\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}$ and  $\frac{3}{4}\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}$.

$\frac{3}{4}\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}$.

It clearly displays a structure similar to that of the von Kármán vortex street where the alternating vortices display opposite circulation, the positive ones travelling slightly above and the negative ones slightly below the centreline. Note that  $\tilde{u} _{3}=0$ uniformly and that

$\tilde{u} _{3}=0$ uniformly and that  $\tilde{u} _{1}$ and

$\tilde{u} _{1}$ and  $\tilde{u} _{2}$ depend on

$\tilde{u} _{2}$ depend on  $x_{1}$ and

$x_{1}$ and  $x_{2}$ but not on

$x_{2}$ but not on  $x_{3}$.

$x_{3}$.

Figure 2. Contours of the magnitude of the phase-averaged velocity  $\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ (normalised by

$\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ (normalised by  $U_{\infty }$) and white unit vectors locally parallel to

$U_{\infty }$) and white unit vectors locally parallel to  $\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$. The large arrow on the left indicates the direction of the free-stream velocity

$\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$. The large arrow on the left indicates the direction of the free-stream velocity  $U_{\infty }$. Using the phase angles shown in figure 1: (a)

$U_{\infty }$. Using the phase angles shown in figure 1: (a)  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=0$; (b)

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=0$; (b)  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=\frac{1}{4}\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}$; (c)

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=\frac{1}{4}\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}$; (c)  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=\frac{1}{2}\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}$; (d)

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=\frac{1}{2}\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}$; (d)  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=\frac{3}{4}\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}$.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=\frac{3}{4}\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}$.

The coherent vorticity field  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\times \tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ is aligned with the spanwise direction and therefore has only one non-zero component

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\times \tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ is aligned with the spanwise direction and therefore has only one non-zero component  $\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}}_{3}$. As shown in Alves Portela, Papadakis & Vassilicos (Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2018) for this exact same flow (see their figure 3), lines of constant vorticity approximately coincide with streamlines of

$\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}}_{3}$. As shown in Alves Portela, Papadakis & Vassilicos (Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2018) for this exact same flow (see their figure 3), lines of constant vorticity approximately coincide with streamlines of  $\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$. As discussed in Hussain (Reference Hussain1983), the streamlines are not necessarily good indicators of the presence of coherent structures, but Lyn et al. (Reference Lyn, Einav, Rodi and Park1995) argue that, apart from the base region in the very near wake where the coherent structures are formed, there is indeed a correspondence between isovorticity and streamlines in identifying coherent structures.

$\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$. As discussed in Hussain (Reference Hussain1983), the streamlines are not necessarily good indicators of the presence of coherent structures, but Lyn et al. (Reference Lyn, Einav, Rodi and Park1995) argue that, apart from the base region in the very near wake where the coherent structures are formed, there is indeed a correspondence between isovorticity and streamlines in identifying coherent structures.

The spectra of the full fluctuating velocity component  $\tilde{u} _{1}+u_{1}^{\prime }$ and

$\tilde{u} _{1}+u_{1}^{\prime }$ and  $\tilde{u} _{2}+u_{2}^{\prime }$ are compared to those of their stochastic counterparts

$\tilde{u} _{2}+u_{2}^{\prime }$ are compared to those of their stochastic counterparts  $u_{1}^{\prime }$ and

$u_{1}^{\prime }$ and  $u_{2}^{\prime }$ in figure 3. As is well known, the shedding frequency is double in the spectrum of

$u_{2}^{\prime }$ in figure 3. As is well known, the shedding frequency is double in the spectrum of  $\tilde{u} _{1}+u_{1}^{\prime }$ compared to the spectrum of

$\tilde{u} _{1}+u_{1}^{\prime }$ compared to the spectrum of  $\tilde{u} _{2}+u_{2}^{\prime }$, and we checked that it corresponds to the distance between coherent vortices in figure 2 (the distance between successive such vortices does not vary much). Note that the energetic peak present at the shedding frequency in the spectrum of

$\tilde{u} _{2}+u_{2}^{\prime }$, and we checked that it corresponds to the distance between coherent vortices in figure 2 (the distance between successive such vortices does not vary much). Note that the energetic peak present at the shedding frequency in the spectrum of  $\tilde{u} _{1}+u_{1}^{\prime }$ is absent in the spectrum of

$\tilde{u} _{1}+u_{1}^{\prime }$ is absent in the spectrum of  $u_{1}^{\prime }$ and that the energetic peak present at the shedding frequency in the spectrum of

$u_{1}^{\prime }$ and that the energetic peak present at the shedding frequency in the spectrum of  $\tilde{u} _{2}+u_{2}^{\prime }$ is absent in the spectrum of

$\tilde{u} _{2}+u_{2}^{\prime }$ is absent in the spectrum of  $u_{2}^{\prime }$.

$u_{2}^{\prime }$.

Figure 3. Power spectrum densities normalised by  $U_{\infty }d$ of (a) streamwise and (b) cross-stream fluctuating velocities, before (dashed lines) and after (full lines) removing the phase component, between

$U_{\infty }d$ of (a) streamwise and (b) cross-stream fluctuating velocities, before (dashed lines) and after (full lines) removing the phase component, between  $x_{1}/d=1$ (blue/top) and

$x_{1}/d=1$ (blue/top) and  $x_{1}/d=8$ (dark green/bottom) offset by one decade every

$x_{1}/d=8$ (dark green/bottom) offset by one decade every  $d$. The dashed line indicates a slope of

$d$. The dashed line indicates a slope of  $-5/3$ and the dotted line indicates (a)

$-5/3$ and the dotted line indicates (a)  $f=2f_{s}$ and (b)

$f=2f_{s}$ and (b)  $f=f_{s}$.

$f=f_{s}$.

Figure 4. Profiles of kinetic energies  $\tilde{k}$ and

$\tilde{k}$ and  $k^{\prime }$ computed from the phase and stochastic components, respectively, along the centreline. The total kinetic energy

$k^{\prime }$ computed from the phase and stochastic components, respectively, along the centreline. The total kinetic energy  $k=\tilde{k}+k^{\prime }$ is also shown for comparison.

$k=\tilde{k}+k^{\prime }$ is also shown for comparison.

In conclusion, the phase-averaged fluctuating velocity  $\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ is representative of the coherent structures in the present flow as it contains the shedding’s characteristic time signature, and its spatial distribution (figure 2) is one of approximately periodic large scale vortices.

$\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$ is representative of the coherent structures in the present flow as it contains the shedding’s characteristic time signature, and its spatial distribution (figure 2) is one of approximately periodic large scale vortices.

In Hussain (Reference Hussain1983) and Hussain, Jeong & Kim (Reference Hussain, Jeong and Kim1987) it is argued that these coherent structures do not necessarily provide a large contribution to the turbulent kinetic energy. Of course, the regions of the flow considered by these authors are much further downstream than the region of the flow studied here. Figure 4 makes it clear that the coherent structures contribute most of the turbulent kinetic energy  $k\equiv \frac{1}{2}\langle |\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}+\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }|^{2}\rangle$ in the near wake considered here and that their contribution (

$k\equiv \frac{1}{2}\langle |\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}+\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }|^{2}\rangle$ in the near wake considered here and that their contribution ( $\tilde{k}\equiv \frac{1}{2}\langle |\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}|^{2}\rangle$) decreases, in the direction of the mean flow, at a faster rate than the kinetic energy associated with the stochastic motions (

$\tilde{k}\equiv \frac{1}{2}\langle |\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}|^{2}\rangle$) decreases, in the direction of the mean flow, at a faster rate than the kinetic energy associated with the stochastic motions ( $k^{\prime }\equiv \frac{1}{2}\langle |\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }|^{2}\rangle$) in line with Hussain (Reference Hussain1983) and Hussain et al. (Reference Hussain, Jeong and Kim1987). (The brackets

$k^{\prime }\equiv \frac{1}{2}\langle |\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }|^{2}\rangle$) in line with Hussain (Reference Hussain1983) and Hussain et al. (Reference Hussain, Jeong and Kim1987). (The brackets  $\langle \cdots \rangle$ symbolise combined time- and spanwise-average operations using approximately

$\langle \cdots \rangle$ symbolise combined time- and spanwise-average operations using approximately  $10^{3}$ snapshots spanning just over

$10^{3}$ snapshots spanning just over  $32$ shedding cycles. The additional spanwise average involves

$32$ shedding cycles. The additional spanwise average involves  $150$ planes in the spanwise direction which is statistically homogeneous. This level of statistics proved sufficient to converge the averages of all the quantities presented in this paper.) Note that

$150$ planes in the spanwise direction which is statistically homogeneous. This level of statistics proved sufficient to converge the averages of all the quantities presented in this paper.) Note that  $k=\tilde{k}+k^{\prime }$. Note also that the Taylor length-based Reynolds number

$k=\tilde{k}+k^{\prime }$. Note also that the Taylor length-based Reynolds number  $Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}}$ varies on the centreline from approximately 120 at

$Re_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}}$ varies on the centreline from approximately 120 at  $x_{1}/d=2$ to approximately 170 at

$x_{1}/d=2$ to approximately 170 at  $x_{1}/d=10$ if it is defined on the basis of

$x_{1}/d=10$ if it is defined on the basis of  $\sqrt{\langle u_{1}^{\prime 2}\rangle }$ and from approximately 100 at

$\sqrt{\langle u_{1}^{\prime 2}\rangle }$ and from approximately 100 at  $x_{1}/d=2$ to approximately 190 at

$x_{1}/d=2$ to approximately 190 at  $x_{1}/d=10$ if it is defined on the basis of

$x_{1}/d=10$ if it is defined on the basis of  $\sqrt{2k^{\prime }/3}$.

$\sqrt{2k^{\prime }/3}$.

In the following section we introduce scale-by-scale energy budgets adapted to the triple decomposition of a velocity field into its mean and its coherent and stochastic fluctuations.

3 Scale-by-scale energy budgets

The most general forms of scale-by-scale energy budget have been derived by Hill (Reference Hill1997, Reference Hill2001, Reference Hill2002a) and Duchon & Robert (Reference Duchon and Robert2000) without making any assumption on the nature of the turbulence. Using the Reynolds decomposition and averaging over time in general but also in the spanwise direction for this paper’s particular flow, this equation (which we refer to as the Kármán–Howarth-Monin–Hill equation) follows from the Navier–Stokes equation and incompressibility and takes the form

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & & \displaystyle \frac{U_{i}^{+}+U_{i}^{-}}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle }{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}+\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle }{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}+\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle }{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}=-2\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}\rangle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \quad -\,\langle (u_{i}^{+}+u_{i}^{-})\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}\rangle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}-\frac{\displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x2202}\left\langle \frac{u_{i}^{+}+u_{i}^{-}}{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\right\rangle }{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}-2\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}p\rangle }{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\frac{1}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle }{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \quad +\,2\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle }{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}-4\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\left(\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle +\frac{1}{4}\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\right\rangle \right),\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & & \displaystyle \frac{U_{i}^{+}+U_{i}^{-}}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle }{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}+\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle }{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}+\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle }{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}=-2\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}\rangle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \quad -\,\langle (u_{i}^{+}+u_{i}^{-})\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}\rangle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}-\frac{\displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x2202}\left\langle \frac{u_{i}^{+}+u_{i}^{-}}{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\right\rangle }{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}-2\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}p\rangle }{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\frac{1}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle }{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \quad +\,2\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle }{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}-4\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\left(\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle +\frac{1}{4}\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\right\rangle \right),\end{eqnarray}$$ where  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\equiv \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}$ in terms of the fluctuating velocity differences

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\equiv \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}$ in terms of the fluctuating velocity differences  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\equiv (\tilde{u} _{i}^{+}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{+})-(\tilde{u} _{i}^{-}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{-})$ (for components

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\equiv (\tilde{u} _{i}^{+}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{+})-(\tilde{u} _{i}^{-}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{-})$ (for components  $i=1,2,3$),

$i=1,2,3$),  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}\equiv U_{i}^{+}-U_{i}^{-}$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}\equiv U_{i}^{+}-U_{i}^{-}$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}p\equiv (\tilde{p}^{+}+p^{\prime +})-(\tilde{p}^{-}+p^{\prime -})$, and the superscripts

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}p\equiv (\tilde{p}^{+}+p^{\prime +})-(\tilde{p}^{-}+p^{\prime -})$, and the superscripts  $+$ and

$+$ and  $-$ distinguish quantities evaluated at positions

$-$ distinguish quantities evaluated at positions  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D743}^{+}\equiv \boldsymbol{x}+\boldsymbol{r}/2$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D743}^{+}\equiv \boldsymbol{x}+\boldsymbol{r}/2$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D743}^{-}\equiv \boldsymbol{x}-\boldsymbol{r}/2$, respectively; e.g.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D743}^{-}\equiv \boldsymbol{x}-\boldsymbol{r}/2$, respectively; e.g.  $u_{i}^{+}\equiv \tilde{u} _{i}^{+}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{+}$ and

$u_{i}^{+}\equiv \tilde{u} _{i}^{+}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{+}$ and  $u_{i}^{-}\equiv \tilde{u} _{i}^{-}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{-}$ are the full fluctuating velocity components at

$u_{i}^{-}\equiv \tilde{u} _{i}^{-}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{-}$ are the full fluctuating velocity components at  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D743}^{+}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D743}^{+}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D743}^{-}$, respectively. Equation (3.1) is written in a six-dimensional reference frame

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D743}^{-}$, respectively. Equation (3.1) is written in a six-dimensional reference frame  $x_{i},r_{i}$ where coordinates

$x_{i},r_{i}$ where coordinates  $x_{i}$ of

$x_{i}$ of  $\boldsymbol{x}$ are associated with a location in physical space and the scale space is the space of all separations and orientations

$\boldsymbol{x}$ are associated with a location in physical space and the scale space is the space of all separations and orientations  $\boldsymbol{r}=(r_{1},r_{2},r_{3})$ between two points (we refer to

$\boldsymbol{r}=(r_{1},r_{2},r_{3})$ between two points (we refer to  $r=|\boldsymbol{r}|$ as a scale). If the average operation is not over time but over realisations, then the extra term

$r=|\boldsymbol{r}|$ as a scale). If the average operation is not over time but over realisations, then the extra term  $\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle /\unicode[STIX]{x2202}t$ can also be present on the left-hand side of (3.1). (Note that an even more general form of the KHMH equation can be obtained without any decomposition and without any averaging operation, see Duchon & Robert (Reference Duchon and Robert2000), Hill (Reference Hill2002a) and Yasuda & Vassilicos (Reference Yasuda and Vassilicos2018).)

$\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle /\unicode[STIX]{x2202}t$ can also be present on the left-hand side of (3.1). (Note that an even more general form of the KHMH equation can be obtained without any decomposition and without any averaging operation, see Duchon & Robert (Reference Duchon and Robert2000), Hill (Reference Hill2002a) and Yasuda & Vassilicos (Reference Yasuda and Vassilicos2018).)

Following Valente & Vassilicos (Reference Valente and Vassilicos2015), Gomes-Fernandes, Ganapathisubramani & Vassilicos (Reference Gomes-Fernandes, Ganapathisubramani and Vassilicos2015) and Alves Portela et al. (Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2017), each term in (3.1), re-written as

$$\begin{eqnarray}{\mathcal{A}}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}={\mathcal{P}}+{\mathcal{T}}_{u}+{\mathcal{T}}_{p}+{\mathcal{D}}_{x}+{\mathcal{D}}_{r}-\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r},\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}{\mathcal{A}}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}={\mathcal{P}}+{\mathcal{T}}_{u}+{\mathcal{T}}_{p}+{\mathcal{D}}_{x}+{\mathcal{D}}_{r}-\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r},\end{eqnarray}$$ is associated with a physical process in the budget of  $\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle$ as follows:

$\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle$ as follows:

(i)

$4{\mathcal{A}}=((U_{i}^{+}+U_{i}^{-})/2)(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle /\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})$ is the mean advection term;

$4{\mathcal{A}}=((U_{i}^{+}+U_{i}^{-})/2)(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle /\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})$ is the mean advection term;(ii)

$4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}=\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle /\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}$ is the nonlinear interscale transfer rate which accounts for the effect of nonlinear interactions in redistributing

$4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}=\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle /\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}$ is the nonlinear interscale transfer rate which accounts for the effect of nonlinear interactions in redistributing  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}$ within the

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}$ within the  $r_{i}$ space and is given by the divergence in scale space of the flux

$r_{i}$ space and is given by the divergence in scale space of the flux  $\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle$;

$\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle$;(iii)

$4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}=(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle )/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}$ is the linear interscale transfer rate. (The term ‘linear’ used here does not mean that a linearisation of the Navier–Stokes equation has been performed.);

$4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}=(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle )/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}$ is the linear interscale transfer rate. (The term ‘linear’ used here does not mean that a linearisation of the Navier–Stokes equation has been performed.);(iv)

$4{\mathcal{P}}=-2\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}\rangle (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{j}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})-\langle (u_{i}^{+}+u_{i}^{-})\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}\rangle (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{j}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})$ can be associated with the production of

$4{\mathcal{P}}=-2\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}\rangle (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{j}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})-\langle (u_{i}^{+}+u_{i}^{-})\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}\rangle (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{j}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})$ can be associated with the production of  $\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle$ by mean flow gradients (see Alves Portela et al. (Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2017) for more details);

$\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle$ by mean flow gradients (see Alves Portela et al. (Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2017) for more details);(v)

$4{\mathcal{T}}_{u}=-\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle ((u_{i}^{+}+u_{i}^{-})/2)\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle /\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}$ is the transport of

$4{\mathcal{T}}_{u}=-\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle ((u_{i}^{+}+u_{i}^{-})/2)\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle /\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}$ is the transport of  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}$ in physical space due to turbulent fluctuations;

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}$ in physical space due to turbulent fluctuations;(vi)

$4{\mathcal{T}}_{p}=-2(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}p\rangle /\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})$ is the pressure-velocity term, equal to

$4{\mathcal{T}}_{p}=-2(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}p\rangle /\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})$ is the pressure-velocity term, equal to  $-2$ times the correlation between fluctuating velocity differences and differences of fluctuating pressure gradient;

$-2$ times the correlation between fluctuating velocity differences and differences of fluctuating pressure gradient;(vii)

$4{\mathcal{D}}_{x}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}(1/2)(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle /\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})$ is the viscous diffusion in physical space;

$4{\mathcal{D}}_{x}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}(1/2)(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle /\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})$ is the viscous diffusion in physical space;(viii)

$4{\mathcal{D}}_{r}=2\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle /\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})$ is the viscous diffusion in scale space. This term is equal to the dissipation

$4{\mathcal{D}}_{r}=2\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle /\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})$ is the viscous diffusion in scale space. This term is equal to the dissipation  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}$ when the two points coincide (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}$ when the two points coincide ( $r=0$) and can be shown (see appendix B in Valente & Vassilicos (Reference Valente and Vassilicos2015)) to be negligible for separations larger than the Taylor microscale; and

$r=0$) and can be shown (see appendix B in Valente & Vassilicos (Reference Valente and Vassilicos2015)) to be negligible for separations larger than the Taylor microscale; and(ix)

$4\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}=4\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}(\langle (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})\rangle +\frac{1}{4}\langle (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})\rangle )$ and

$4\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}=4\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}(\langle (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})\rangle +\frac{1}{4}\langle (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})\rangle )$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}$ is actually the two-point average dissipation rate

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}$ is actually the two-point average dissipation rate  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}=(\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}^{+}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}^{-})/2$ as it equals

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}=(\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}^{+}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}^{-})/2$ as it equals  $\frac{1}{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}(\langle (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}u_{j}^{+}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}^{+})(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}u_{j}^{+}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}^{+})\rangle +\langle (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}u_{j}^{-}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}^{-})(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}u_{j}^{-}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}^{-})\rangle )$.

$\frac{1}{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}(\langle (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}u_{j}^{+}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}^{+})(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}u_{j}^{+}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}^{+})\rangle +\langle (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}u_{j}^{-}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}^{-})(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}u_{j}^{-}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}^{-})\rangle )$.

With the triple decomposition introduced in § 2 one can decompose the second-order structure function  $\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle$ into a stochastic and a coherent part, i.e.

$\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle$ into a stochastic and a coherent part, i.e.  $\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle =\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\rangle +\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle$ where

$\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}\rangle =\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\rangle +\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle$ where  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\equiv \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}$ with

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\equiv \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}$ with  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\equiv \tilde{u} _{i}^{+}-\tilde{u} _{i}^{-}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\equiv \tilde{u} _{i}^{+}-\tilde{u} _{i}^{-}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\equiv \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }$ with

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\equiv \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }$ with  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\equiv {u_{i}^{\prime }}^{+}-{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{-}$. The fluctuating pressure difference

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\equiv {u_{i}^{\prime }}^{+}-{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{-}$. The fluctuating pressure difference  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}p$ is also decomposed in a similar way, i.e.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}p$ is also decomposed in a similar way, i.e.  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}p=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{p}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}p^{\prime }$ where

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}p=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{p}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}p^{\prime }$ where  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{p}\equiv \tilde{p}^{+}-\tilde{p}^{-}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{p}\equiv \tilde{p}^{+}-\tilde{p}^{-}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}p^{\prime }\equiv p^{\prime +}-p^{\prime -}$.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}p^{\prime }\equiv p^{\prime +}-p^{\prime -}$.

This decomposition into stochastic and coherent fluctuations warrants new scale-by-scale energy budgets to be derived and this was done by Thiesset et al. (Reference Thiesset, Danaila and Antonia2014) by neglecting mean flow velocity differences  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}$. The resulting slightly more general equations for

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}$. The resulting slightly more general equations for  $\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle$ and

$\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle$ and  $\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\rangle$ without neglecting

$\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\rangle$ without neglecting  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}$ are, respectively,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}$ are, respectively,

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & & \displaystyle \frac{U_{i}^{+}+U_{i}^{-}}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle +\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle +\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle +\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \quad =-\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }({u_{j}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{j}^{\prime }}^{-})\rangle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}}-2\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }\rangle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}}-\left\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }({u_{j}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{j}^{\prime }}^{-})\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}}\right\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \qquad -\,2\left\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}}\right\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \qquad -\,\left\langle \frac{\tilde{u} _{i}^{+}+\tilde{u} _{i}^{-}}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle -\left\langle \frac{{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{-}}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle -2\left\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}p^{\prime }}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \qquad +\,\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\left\langle \frac{1}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}}\right\rangle +2\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}}\right\rangle -4\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\left(\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle +\frac{1}{4}\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\right\rangle \right)\nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & & \displaystyle \frac{U_{i}^{+}+U_{i}^{-}}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle +\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle +\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle +\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \quad =-\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }({u_{j}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{j}^{\prime }}^{-})\rangle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}}-2\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }\rangle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}}-\left\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }({u_{j}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{j}^{\prime }}^{-})\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}}\right\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \qquad -\,2\left\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}}\right\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \qquad -\,\left\langle \frac{\tilde{u} _{i}^{+}+\tilde{u} _{i}^{-}}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle -\left\langle \frac{{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{-}}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle -2\left\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}p^{\prime }}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \qquad +\,\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\left\langle \frac{1}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}}\right\rangle +2\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}}\right\rangle -4\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\left(\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle +\frac{1}{4}\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\right\rangle \right)\nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$and

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & & \displaystyle \frac{U_{i}^{+}+U_{i}^{-}}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\rangle +\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\rangle +2\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{j}\rangle +\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \quad =-\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}(\tilde{u} _{j}^{+}+\tilde{u} _{j}^{-})\rangle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}}-2\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{j}\rangle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}}+\left\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }({u_{j}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{j}^{\prime }}^{-})\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}}\right\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \qquad +\,\left\langle 2\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}}\right\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \qquad -\,\left\langle \frac{\tilde{u} _{i}^{+}+\tilde{u} _{i}^{-}}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle -\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}[({u_{i}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{-})\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{j}]\right\rangle -2\left\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\tilde{p}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \qquad +\,\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\left\langle \frac{1}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}}\right\rangle +2\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}}\right\rangle -4\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\left(\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle +\frac{1}{4}\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\right\rangle \right).\qquad\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & & \displaystyle \frac{U_{i}^{+}+U_{i}^{-}}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\rangle +\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\rangle +2\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{j}\rangle +\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \quad =-\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}(\tilde{u} _{j}^{+}+\tilde{u} _{j}^{-})\rangle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}}-2\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{j}\rangle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}U_{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}}+\left\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }({u_{j}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{j}^{\prime }}^{-})\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}}\right\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \qquad +\,\left\langle 2\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}}\right\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \qquad -\,\left\langle \frac{\tilde{u} _{i}^{+}+\tilde{u} _{i}^{-}}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle -\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}[({u_{i}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{-})\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{j}]\right\rangle -2\left\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\tilde{p}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle \nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle \qquad +\,\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\left\langle \frac{1}{2}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j}}\right\rangle +2\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j}}\right\rangle -4\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}\left(\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i}}\right\rangle +\frac{1}{4}\left\langle \frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{j}}{\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i}}\right\rangle \right).\qquad\end{eqnarray}$$Evidently both equations (3.3) and (3.4) are rather similar to the KHMH equation (3.1) and we therefore make use of similar notation to identify the individual terms

$$\begin{eqnarray}{\mathcal{A}}^{\prime }+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}^{\prime }={\mathcal{P}}_{U}^{\prime }+{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+{\mathcal{T}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+{\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}^{\prime }+{\mathcal{T}}_{p^{\prime }}^{\prime }+{\mathcal{D}}_{x}^{\prime }+{\mathcal{D}}_{r}^{\prime }-\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}^{\prime }\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}{\mathcal{A}}^{\prime }+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}^{\prime }={\mathcal{P}}_{U}^{\prime }+{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+{\mathcal{T}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+{\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}^{\prime }+{\mathcal{T}}_{p^{\prime }}^{\prime }+{\mathcal{D}}_{x}^{\prime }+{\mathcal{D}}_{r}^{\prime }-\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}^{\prime }\end{eqnarray}$$for (3.3) and

$$\begin{eqnarray}\tilde{{\mathcal{A}}}+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{\tilde{u} }+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{U}=\tilde{{\mathcal{P}}}_{U}-{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{u} }+\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}+\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{p}}+\tilde{{\mathcal{D}}}_{x}+\tilde{{\mathcal{D}}}_{r}-\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}}_{r}\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\tilde{{\mathcal{A}}}+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{\tilde{u} }+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{U}=\tilde{{\mathcal{P}}}_{U}-{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{u} }+\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}+\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{p}}+\tilde{{\mathcal{D}}}_{x}+\tilde{{\mathcal{D}}}_{r}-\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}}_{r}\end{eqnarray}$$ for (3.4). Here,  $4{\mathcal{A}}^{\prime }$,

$4{\mathcal{A}}^{\prime }$,  $4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }$,

$4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }$,  $4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }$ and

$4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }$ and  $4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}^{\prime }$ correspond to the first, second, third and fourth terms in the first line of (3.3) and

$4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}^{\prime }$ correspond to the first, second, third and fourth terms in the first line of (3.3) and  $4\tilde{{\mathcal{A}}}$,

$4\tilde{{\mathcal{A}}}$,  $4\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{\tilde{u} }$,

$4\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{\tilde{u} }$,  $4\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}$ and

$4\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}$ and  $4\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{U}$ correspond to the first, second, third and fourth terms in the first line of (3.4). Here,

$4\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{U}$ correspond to the first, second, third and fourth terms in the first line of (3.4). Here,  $4{\mathcal{P}}_{U}^{\prime }$ and

$4{\mathcal{P}}_{U}^{\prime }$ and  $4\tilde{{\mathcal{P}}}_{U}$ correspond to the sum of the first and second terms in the second line of (3.3) and (3.4), respectively. For the same reasons given for

$4\tilde{{\mathcal{P}}}_{U}$ correspond to the sum of the first and second terms in the second line of (3.3) and (3.4), respectively. For the same reasons given for  $4{\mathcal{P}}$ by Alves Portela et al. (Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2017),

$4{\mathcal{P}}$ by Alves Portela et al. (Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2017),  $4{\mathcal{P}}_{U}^{\prime }$ and

$4{\mathcal{P}}_{U}^{\prime }$ and  $4\tilde{{\mathcal{P}}}_{U}$ are production terms of

$4\tilde{{\mathcal{P}}}_{U}$ are production terms of  $\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle$ and

$\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle$ and  $\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\rangle$, respectively, and

$\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\rangle$, respectively, and  $4{\mathcal{P}}=4{\mathcal{P}}_{U}^{\prime }+4\tilde{{\mathcal{P}}}_{U}$. The term

$4{\mathcal{P}}=4{\mathcal{P}}_{U}^{\prime }+4\tilde{{\mathcal{P}}}_{U}$. The term  $4{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }\equiv -\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }({u_{j}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{j}^{\prime }}^{-})(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j})\rangle -\langle 2\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j})\rangle$ appears with opposite signs in (3.3) and (3.4) and is therefore the production term which exchanges energy at given

$4{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }\equiv -\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }({u_{j}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{j}^{\prime }}^{-})(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{j})\rangle -\langle 2\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{j}^{\prime }(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{j})\rangle$ appears with opposite signs in (3.3) and (3.4) and is therefore the production term which exchanges energy at given  $\boldsymbol{x}$ and

$\boldsymbol{x}$ and  $\boldsymbol{r}$ between the stochastic and the coherent fluctuating motions. The spatial transport terms

$\boldsymbol{r}$ between the stochastic and the coherent fluctuating motions. The spatial transport terms  $4{\mathcal{T}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }$ and

$4{\mathcal{T}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }$ and  $4{\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}^{\prime }$ are the first and second terms in the fourth line of (3.3) and the stochastic pressure-stochastic velocity term

$4{\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}^{\prime }$ are the first and second terms in the fourth line of (3.3) and the stochastic pressure-stochastic velocity term  $4{\mathcal{T}}_{p^{\prime }}^{\prime }$ is the third term on this line. Similarly, the transport terms

$4{\mathcal{T}}_{p^{\prime }}^{\prime }$ is the third term on this line. Similarly, the transport terms  $4\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{u} }$ and

$4\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{u} }$ and  $4\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}$ are the first and second terms in the fourth line of (3.4) and the coherent pressure-coherent velocity term

$4\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}$ are the first and second terms in the fourth line of (3.4) and the coherent pressure-coherent velocity term  $4\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{p}}$ is the third term on this line. The remaining terms are the diffusion terms

$4\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{p}}$ is the third term on this line. The remaining terms are the diffusion terms  $4\tilde{{\mathcal{D}}}_{x}$,

$4\tilde{{\mathcal{D}}}_{x}$,  $4\tilde{{\mathcal{D}}}_{r}$,

$4\tilde{{\mathcal{D}}}_{r}$,  $4{\mathcal{D}}_{x}^{\prime }$ and

$4{\mathcal{D}}_{x}^{\prime }$ and  $4{\mathcal{D}}_{r}^{\prime }$ and the dissipation terms

$4{\mathcal{D}}_{r}^{\prime }$ and the dissipation terms  $4\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}}_{r}$ and

$4\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}}_{r}$ and  $4\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}^{\prime }$ which are defined exactly as the diffusion and dissipation terms in the KHMH equation (3.1) and (3.2) but for the coherent and stochastic velocity fields, respectively, rather than for the total fluctuating velocity field.

$4\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}^{\prime }$ which are defined exactly as the diffusion and dissipation terms in the KHMH equation (3.1) and (3.2) but for the coherent and stochastic velocity fields, respectively, rather than for the total fluctuating velocity field.

Adding (3.5) with (3.6) results in the KHMH equation by combining terms with tilde and primes together (e.g.  ${\mathcal{A}}={\mathcal{A}}^{\prime }+\tilde{{\mathcal{A}}}$,

${\mathcal{A}}={\mathcal{A}}^{\prime }+\tilde{{\mathcal{A}}}$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}^{\prime }+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{U}$, etc.) but also by noticing that

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}^{\prime }+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{U}$, etc.) but also by noticing that

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{\tilde{u} }+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{\tilde{u} }+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}\end{eqnarray}$$and

$$\begin{eqnarray}{\mathcal{T}}_{u}={\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}^{\prime }+{\mathcal{T}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{u} }+\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }},\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}{\mathcal{T}}_{u}={\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}^{\prime }+{\mathcal{T}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{u} }+\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }},\end{eqnarray}$$which are the nonlinear interscale and interspace transfer terms.

The terms  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }$ and  $\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{\tilde{u} }$ can be interpreted as interscale transfer terms of either

$\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{\tilde{u} }$ can be interpreted as interscale transfer terms of either  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}$ or

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}$ or  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}$. Here,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}$. Here,  $4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }\equiv (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle$ represents the interscale transfer of energy associated with the stochastic motions by the stochastic motions (i.e. interscale transfer of

$4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }\equiv (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle$ represents the interscale transfer of energy associated with the stochastic motions by the stochastic motions (i.e. interscale transfer of  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}$ by

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}$ by  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }$). Similarly,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }$). Similarly,  $4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }\equiv (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle$ represents the interscale transfer of the energy associated with the stochastic motions by the coherent motions (i.e. interscale transfer of

$4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }\equiv (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}\rangle$ represents the interscale transfer of the energy associated with the stochastic motions by the coherent motions (i.e. interscale transfer of  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}$ by

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}$ by  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$), and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}$), and  $4\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{\tilde{u} }\equiv (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\rangle$ represents the interscale transfer of the energy associated with the coherent motions by the coherent motions (i.e. interscale transfer of

$4\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{\tilde{u} }\equiv (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}\rangle$ represents the interscale transfer of the energy associated with the coherent motions by the coherent motions (i.e. interscale transfer of  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}$ by

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}$ by  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}$). The term

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{u} _{i}$). The term  $4\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}$ can be written as the difference between two interscale transfer terms: the interscale transfer by the stochastic velocity field of the total fluctuating energy and

$4\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}$ can be written as the difference between two interscale transfer terms: the interscale transfer by the stochastic velocity field of the total fluctuating energy and  $4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }$, i.e.

$4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }$, i.e.  $4\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}=4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{u^{\prime }}-4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }$ where

$4\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}=4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{u^{\prime }}-4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }$ where  $4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{u^{\prime }}\equiv (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }|\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}|^{2}\rangle$. Hence, combining

$4\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{u^{\prime }}\equiv (\unicode[STIX]{x2202}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}r_{i})\langle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}u_{i}^{\prime }|\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}|^{2}\rangle$. Hence, combining  $\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}$ with

$\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}$ with  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }$ results in the interscale transfer of the total fluctuating energy by the stochastic motions (i.e. interscale transfer of

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}^{\prime }$ results in the interscale transfer of the total fluctuating energy by the stochastic motions (i.e. interscale transfer of  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}$ by

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{2}$ by  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }$) so that (3.7) can be written as

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }$) so that (3.7) can be written as

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{u^{\prime }}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{\tilde{u} }.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{u^{\prime }}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{\tilde{u} }.\end{eqnarray}$$This proves to be an important equation in § 5.

The terms  ${\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}^{\prime }$,

${\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}^{\prime }$,  ${\mathcal{T}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }$,

${\mathcal{T}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }$,  $\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{u} }$ represent turbulent transport in physical space. Specifically,

$\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{u} }$ represent turbulent transport in physical space. Specifically,  $4{\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}^{\prime }\equiv -\langle (({u_{i}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{-})/2)(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})\rangle$ represents interspace transport of stochastic turbulent energy by stochastic fluctuations,

$4{\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}^{\prime }\equiv -\langle (({u_{i}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{-})/2)(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})\rangle$ represents interspace transport of stochastic turbulent energy by stochastic fluctuations,  $4{\mathcal{T}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }\equiv -\langle (({\tilde{u} _{i}}^{+}+{\tilde{u} _{i}}^{-})/2)(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})\rangle$, represents interspace transport of stochastic turbulent energy by coherent fluctuations, and

$4{\mathcal{T}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }\equiv -\langle (({\tilde{u} _{i}}^{+}+{\tilde{u} _{i}}^{-})/2)(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q^{\prime 2}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})\rangle$, represents interspace transport of stochastic turbulent energy by coherent fluctuations, and  $\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{u} }\equiv -\langle (({\tilde{u} _{i}}^{+}+{\tilde{u} _{i}}^{-})/2)(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})\rangle$ represents interspace transport of coherent fluctuating energy by coherent fluctuations. The term

$\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{u} }\equiv -\langle (({\tilde{u} _{i}}^{+}+{\tilde{u} _{i}}^{-})/2)(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{q}^{2}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})\rangle$ represents interspace transport of coherent fluctuating energy by coherent fluctuations. The term  $-4\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}$ is the difference between

$-4\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}$ is the difference between  $4{\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}^{\prime }$ and the spatial transport of the total fluctuating energy by the two-point-average stochastic velocity, i.e.

$4{\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}^{\prime }$ and the spatial transport of the total fluctuating energy by the two-point-average stochastic velocity, i.e.  $4\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}=4{\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}-4{\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}^{\prime }$ were

$4\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathcal{P}}_{\tilde{u} }}=4{\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}-4{\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}^{\prime }$ were  $4{\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}\equiv \langle (({u_{i}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{-})/2)(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}|\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}|^{2}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})\rangle$. This allows rewriting (3.8) as follows:

$4{\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}\equiv \langle (({u_{i}^{\prime }}^{+}+{u_{i}^{\prime }}^{-})/2)(\unicode[STIX]{x2202}|\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\boldsymbol{u}^{\prime }+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}|^{2}/\unicode[STIX]{x2202}x_{i})\rangle$. This allows rewriting (3.8) as follows:

$$\begin{eqnarray}{\mathcal{T}}_{u}={\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}+{\mathcal{T}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{u} }.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}{\mathcal{T}}_{u}={\mathcal{T}}_{u^{\prime }}+{\mathcal{T}}_{\tilde{u} }^{\prime }+\tilde{{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tilde{u} }.\end{eqnarray}$$In the following section we compare the signs and magnitudes of the orientation-averaged terms in (3.5) and (3.6) in the near field turbulent planar wake.

4 Orientation-averaged scale-by-scale energy budgets in the near wake of a square prism

Each term,  $Q$, in (3.5) and (3.6) is an average in time and spanwise direction and is therefore a function of planar coordinates

$Q$, in (3.5) and (3.6) is an average in time and spanwise direction and is therefore a function of planar coordinates  $(x_{1},x_{2})$ and two-point separation vector

$(x_{1},x_{2})$ and two-point separation vector  $\boldsymbol{r}$, i.e.

$\boldsymbol{r}$, i.e.  $Q=Q(x_{1},x_{2},\boldsymbol{r})$. We set

$Q=Q(x_{1},x_{2},\boldsymbol{r})$. We set  $r_{3}=0$ and define the orientation-averaged quantity

$r_{3}=0$ and define the orientation-averaged quantity  $Q^{a}$ by integrating

$Q^{a}$ by integrating  $Q$ over the angle

$Q$ over the angle  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D703}$ defined by

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D703}$ defined by  $r_{1}=r\cos \unicode[STIX]{x1D703}$,

$r_{1}=r\cos \unicode[STIX]{x1D703}$,  $r_{2}=r\sin \unicode[STIX]{x1D703}$ which also defines the radius (and length scale)

$r_{2}=r\sin \unicode[STIX]{x1D703}$ which also defines the radius (and length scale)  $r$ as follows:

$r$ as follows:  $Q^{a}(x_{1},x_{2},r)\equiv (1/2\unicode[STIX]{x03C0})\int _{0}^{2\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}}Q\,\text{d}\unicode[STIX]{x1D703}$. Such scale-space orientation-averaging has already been used by Alves Portela et al. (Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2017) and Gomes-Fernandes et al. (Reference Gomes-Fernandes, Ganapathisubramani and Vassilicos2015) to study the terms in the KHMH equation (3.2). We verified that the KHMH equation, (3.1), is sufficiently well balanced numerically, as the difference between its left-hand and right-hand sides is two orders of magnitude smaller than

$Q^{a}(x_{1},x_{2},r)\equiv (1/2\unicode[STIX]{x03C0})\int _{0}^{2\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}}Q\,\text{d}\unicode[STIX]{x1D703}$. Such scale-space orientation-averaging has already been used by Alves Portela et al. (Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2017) and Gomes-Fernandes et al. (Reference Gomes-Fernandes, Ganapathisubramani and Vassilicos2015) to study the terms in the KHMH equation (3.2). We verified that the KHMH equation, (3.1), is sufficiently well balanced numerically, as the difference between its left-hand and right-hand sides is two orders of magnitude smaller than  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}$ for all

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}$ for all  $r$ investigated here, and even smaller than that when the two sides are orientation-averaged in scale-space plane

$r$ investigated here, and even smaller than that when the two sides are orientation-averaged in scale-space plane  $r_{3}=0$. We also checked that every term in (3.1) is indeed equal to the sum of its two corresponding terms in (3.3) and (3.4), for example

$r_{3}=0$. We also checked that every term in (3.1) is indeed equal to the sum of its two corresponding terms in (3.3) and (3.4), for example  ${\mathcal{A}}={\mathcal{A}}^{\prime }+\tilde{{\mathcal{A}}}$,

${\mathcal{A}}={\mathcal{A}}^{\prime }+\tilde{{\mathcal{A}}}$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}^{\prime }+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{U}$, etc.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}_{U}^{\prime }+\tilde{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6F1}}_{U}$, etc.

In figure 5 we plot all the orientation-averaged terms in (3.5) versus  $r/d$ in the range

$r/d$ in the range  $0\leqslant r/d\leqslant 1.1$ at two centreline positions,

$0\leqslant r/d\leqslant 1.1$ at two centreline positions,  $(x_{1},x_{2})=(2d,0)$ and

$(x_{1},x_{2})=(2d,0)$ and  $(8d,0)$. These terms are plotted normalised by

$(8d,0)$. These terms are plotted normalised by  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}^{a}$ which, for

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}^{a}$ which, for  $r$ not much larger than

$r$ not much larger than  $d$, is approximately equal to

$d$, is approximately equal to  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D700}_{r}^{\prime a}$ (see Alves Portela et al. Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2018) and to the one-point dissipation rate