1 Introduction

A surprising result in the last two decades of research on bilingualism is that the language not in use is also active in both language comprehension (e.g., Guo, Misra, Tam & Kroll, Reference Guo, Misra, Tam and Kroll2012; Thierry & Wu, Reference Thierry and Wu2007; Wu & Thierry, Reference Wu and Thierry2010, Reference Wu and Thierry2012) and production (e.g., Costa, Caramazza & Sebastian-Galles, Reference Costa, Caramazza and Sebastian-Galles2000; Spalek, Hoshino, Wu, Damian & Thierry, Reference Spalek, Hoshino, Wu, Damian and Thierry2014). This observation triggered a surge of research to investigate the language control mechanism that guarantees the use of the target language in the face of parallel activation of both languages (for reviews see Baus, Branzi & Costa, Reference Baus, Branzi, Costa and Schwieter2015; Bobb & Wodniecka, Reference Bobb and Wodniecka2013; Kroll, Bobb, Misra & Guo, Reference Kroll, Bobb, Misra and Guo2008). According to the Inhibitory Control Model (IC Model, Green, Reference Green1998), language control entails competition between language task schemas outside the lexical-semantic system and reactive inhibition on the lexical items of the non-target language within the lexical-semantic system.

A major issue in the exploration of language control mechanisms concerns the relationship between language control and executive functions. One line of research has asked whether dual language experience improves bilinguals’ executive functions (Bialystok, Craik & Luk, Reference Bialystok, Craik and Luk2012; Paap, Johnson & Sawi, Reference Paap, Johnson and Sawi2015). Some studies showed that bilinguals perform better than their monolingual counterparts in tasks tapping into executive functions, such as inhibition (Simon task, Bialystok, Craik, Klein & Viswanathan, Reference Bialystok, Craik, Klein and Viswanathan2004; but see Kirk, Fiala, Scott-Brown & Kempe, Reference Kirk, Fiala, Scott-Brown and Kempe2014; Morton & Harper, Reference Morton and Harper2007; flanker task, Abutalebi, Guidi, Borsa, Canini, Della Rosa, Parris & Weekes, Reference Abutalebi, Guidi, Borsa, Canini, Della Rosa, Parris and Weekes2015; Calabria, Hernández, Martin & Costa, Reference Calabria, Hernández, Martin and Costa2011; Costa, Hernández & Sebastián-Gallés, Reference Costa, Hernández and Sebastián-Gallés2008; but see Antón, Duñabeitia, Estévez, Hernández, Castillo, Fuentes, Davidson & Carreiras, Reference Antón, Duñabeitia, Estévez, Hernández, Castillo, Fuentes, Davidson and Carreiras2014; Stroop task, Bialystok, Craik & Luk, Reference Bialystok, Craik and Luk2008; but see Duñabeitia, Hernández, Antón, Macizo, Estévez, Fuentes & Carreiras, Reference Duñabeitia, Hernández, Antón, Macizo, Estévez, Fuentes and Carreiras2014; Kousaie & Phillips, Reference Kousaie and Phillips2012a), shifting (switching task, Prior & Macwhinney, Reference Prior and Macwhinney2010; Prior & Gollan, Reference Prior and Gollan2011; Tao, Taft & Gollan, Reference Tao, Taft and Gollan2015; but see Paap, Myuz, Anders, Bockelman, Mikulinsky & Sawi, Reference Paap, Myuz, Anders, Bockelman, Mikulinsky and Sawi2017) and working memory (Bialystok et al., Reference Bialystok, Craik, Klein and Viswanathan2004; Morales, Calvo & Bialystok, Reference Morales, Calvo and Bialystok2013; but see Bialystok et al., Reference Bialystok, Craik and Luk2008), especially when the demands of executive functions are high (Hernández, Martin, Barceló & Costa, Reference Hernández, Martin, Barceló and Costa2013; Martin-Rhee & Bialystok, Reference Martin-Rhee and Bialystok2008). In contrast, some other studies failed to find robust difference between bilinguals and monolinguals in any executive functions (Clare, Whitaker, Martyr, Martin-Forbes, Bastable, Pye, Quinn, Thomas, Gathercole & Hindle, Reference Clare, Whitaker, Martyr, Martin-Forbes, Bastable, Pye, Quinn, Thomas, Gathercole and Hindle2016; Paap & Greenberg, Reference Paap and Greenberg2013; Paap, Johnson & Sawi, Reference Paap, Johnson and Sawi2014; Paap & Sawi, Reference Paap and Sawi2014). Some researchers believed that even if this difference exists, it was very limited (Bosma, Hoekstra, Versloot & Blom, Reference Bosma, Hoekstra, Versloot and Blom2017) and was exhibited only under certain conditions (Gathercole. Thomas, Kennedy, Prys, Yong, Guasch, Roberts, Hughes & Jones, Reference Gathercole, Thomas, Kennedy, Prys, Yong, Guasch, Roberts, Hughes and Jones2014; Paap et al., Reference Paap, Johnson and Sawi2015; Von Bastian, Souza & Gade, Reference Von Bastian, Souza and Gade2016).

Based on the mixed pattern of data available, it has been suggested that the divergent results may be attributed to methodological issues (e.g., task-specific factors) and to differences among the bilingual groups under investigation (e.g., older participants vs. younger adults who were at the prime of the cognitive abilities) (e.g., Kroll & Bialystok, Reference Kroll and Bialystok2013). In addition, the varying profiles of bilinguals across studies may be another contributing factor to the incongruence in findings: bilinguals in some studies would have been described as monolinguals in others (Surrain & Luk, Reference Surrain and Luk2019). Nonetheless, pointed out by Green and Abutalebi (Reference Green and Abutalebi2013), for the reported associations between the bilingual language use experience and the difference in general executive control, the precise underlying mechanisms have not been determined: there are possibilities of overlapping and (co-activation of) separate control networks for bilingual language control and general executive control mechanisms. Indeed, the reported difference between bilinguals and monolinguals in executive functions seems to be rooted in the assumption that there is at least partial overlap between them (e.g., Bialystok, Reference Bialystok2011). The determination of the specific relationship between the two types of control will shed light on the nature and plasticity of the executive and language control mechanisms and bilingualism per se (also see Prior & Gollan, Reference Prior and Gollan2013 for related discussions).

Another line of research has investigated whether individuals’ executive functions impact language control processes. The evidence available suggests that general inhibition or shifting functions may predict language control processes. For example, Linck, Schwieter and Sunderman (Reference Linck, Schwieter and Sunderman2012) reported that when trilinguals switched from their weaker language to their dominant language, better inhibitory control, as reflected by a smaller Simon effect, correlated with smaller language switch costs. They speculated that individuals with better inhibitory control may exert inhibition on the non-target language more rapidly, leading to smaller language switch costs. Furthermore, Gross and Kaushanskaya (Reference Gross and Kaushanskaya2018) found that the better bilingual children's task-shifting ability, the fewer the cross-language errors and the higher the efficiency of lexical selection. Liu and colleagues also found that low proficient bilinguals with high inhibitory ability (Liu, Rossi, Zhou & Chen, Reference Liu, Rossi, Zhou and Chen2014) or high shifting ability (Liu, Fan, Rossi, Yao & Chen, Reference Liu, Fan, Rossi, Yao and Chen2016a) showed symmetrical and smaller language switch costs, while those with low inhibitory ability or low shifting ability showed asymmetrical and larger language switch costs. The asymmetrical pattern is the one typically associated with low proficiency. These results suggest that domain general cognitive abilities may compensate, at least in part, for language proficiency. Other studies (e.g., Liu, Liang, Dunlap, Fan & Chen, Reference Liu, Liang, Dunlap, Fan and Chen2016b) have shown that general inhibition training can improve individuals’ inhibitory control ability, leading low proficient bilinguals with low inhibitory ability to produce symmetrical and smaller language switch costs following training.

Executive functions have been hypothesized to include at least three components (Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter & Wager, Reference Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter and Wager2000), namely inhibition (inhibiting prepotent responses or suppressing distractor interference, see Friedman & Miyake, Reference Friedman and Miyake2004), shifting (shifting between tasks or mental sets), and updating (updating and monitoring working memory representations). However, the contributions of various executive functions for bilingual language control processes have been largely under-investigated. To our knowledge, only one behavioral study by Jylkkä, Lehtonen, Lindholm, Kuusakoski and Laine (Reference Jylkkä, Lehtonen, Lindholm, Kuusakoski and Laine2018) investigated how inhibitory control and shifting affect bilingual lexical selection during production. Critical to the current discussion, Jylkkä and colleagues found that the flanker and Simon effects did not mediate language switch costs. Additionally, the Number-Letter switching effect did not predict the language switch costs in L1, although it positively correlated with these costs in L2. In contrast with the patterns reviewed above, these behavioral results suggest a limited role of inhibitory control during bilingual lexical selection and indicate that bilingual language control mechanism seems to engage the shifting aspect of the general executive control to a certain degree.

It is notable that these findings contrasted with the results of an ERP study (Wu & Thierry, Reference Wu and Thierry2013), in which bilinguals performed a flanker task in mixed or single language contexts. It was found that the P300 component was attenuated in a dual language context, as compared to a single language context. Critically, such P300 deflections were present in incongruent trials, but not in congruent trials. Since P300 has been taken to reflect attentional control, the researchers concluded that bilinguals’ inhibitory control was enhanced by the bilingual context where conflicts need to be resolved. These findings suggest an association between bilingual language control and inhibitory control.

Taken together, the relationship between bilingual language control and different components of the general executive control still remains controversial. Also, as revealed in the review of the current literature, no study has directly explored the role of updating in bilingual language control. Furthermore, although behavioral data provide invaluable evidence, event-related potentials (ERPs) provide complementary evidence for examining different phases of language control with higher temporal resolution. Indeed, it has been well-documented that ERPs are more likely to reveal effects that may not present in behavioral data (e.g., Guo et al., Reference Guo, Misra, Tam and Kroll2012; Kousaie & Phillips, Reference Kousaie and Phillips2012b; Ma, Chen, Guo & Kroll, Reference Ma, Chen, Guo and Kroll2017; van Hell & Kroll, Reference Van Hell, Kroll, Altarriba and Isurin2013). Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the predictions of the three executive function components on language control during bilingual word production with ERPs. We used a flanker task, a switching task and an n-back task to tap into inhibition, shifting, and updating, respectively. Although the components of executive functions are not directly equivalent to the performance on any one task, we hypothesized that a comparison of performance on these tasks and their relation to language production would reveal new information about cognitive and language control (e.g., Valian, Reference Valian2015).

The flanker task (Eriksen & Eriksen, Reference Eriksen and Eriksen1974) is a common task to tap into inhibition: more specifically, the interference suppression function (Bunge, Dudukovic, Thomason, Vaidya & Gabrieli, Reference Bunge, Dudukovic, Thomason, Vaidya and Gabrieli2002). Typically, participants are asked to identify the target which is flanked by two stimuli on both sides. The flanker stimuli can trigger the same response as the target (the congruent condition), the opposite response to the target (the incongruent condition), or no response (the neutral condition). Response times in the incongruent condition are usually longer than those in the congruent condition and the difference is defined as the flanker effect, which is considered as an index of inhibitory control (e.g., Kopp, Rist & Mattler, Reference Kopp, Rist and Mattler1996). Different from the standard Eriksen Flanker task with letters, we used an arrow-flanker variant in the present study.

The switching task is frequently used to probe into the shifting component of executive functions (e.g., Miyake et al., Reference Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter and Wager2000). In the present study, we adopted a parity/magnitude switching task, where participants were required to switch between judging the parity (odd or even) and the magnitude (larger or smaller than 5) of single digits. The performance on switch trials (where the present task was different from the previous one) is typically worse than that on non-switch trials (where the present task was the same as the previous one), resulting in switch costs (Rogers & Monsell, Reference Rogers and Monsell1995). It is widely accepted that switch costs result from both the (re)configuration of the currently related task set and the inhibition of the currently unrelated task set (for reviews see Kiesel, Steinhauser, Wendt, Falkenstein, Jost, Philipp & Koch, Reference Kiesel, Steinhauser, Wendt, Falkenstein, Jost, Philipp and Koch2010; Monsell, Reference Monsell2003; Vandierendonck, Liefooghe & Verbruggen, Reference Vandierendonck, Liefooghe and Verbruggen2010).

The n-back task is a classic task to assess updating (Owen, McMillan, Laird & Bullmore, Reference Owen, McMillan, Laird and Bullmore2005). A typical n-back task requires participants to make a judgment about whether the current stimulus is the same or at the same location as the one in the n-back trial. To complete the task, participants need to update the information in working memory and keep track of the updating information in the latest n trials (Chatham, Herd, Brant, Hazy, Miyake, O'Reilly & Friedman, Reference Chatham, Herd, Brant, Hazy, Miyake, O'Reilly and Friedman2011). In the present study, we used two composite indices from the Signal Detection Theory, the d L (discrimination index) and C L (bias index), to reflect participants’ working memory sensitivity and response strategy (Haatveit, Sundet, Hugdahl, Ueland, Melle & Andreassen, Reference Haatveit, Sundet, Hugdahl, Ueland, Melle and Andreassen2010; Kane, Conway, Miura & Colflesh, Reference Kane, Conway, Miura and Colflesh2007; Meule, Reference Meule2017).

In the present study, we adopted a cued language switching task to investigate the language control processes during bilingual word production. This task usually requires participants to name pictures or digits in the corresponding language indicated by a cue. Similar to task switching, the language switching task also contains switch trials (the target language in the current trial is different from that in the previous trial) and non-switch trials (the current target language is the same as the previous one). A number of behavioral studies have revealed that naming latencies in switch trials are longer than those in non-switch trials, yielding language switch costs (Costa & Santesteban, Reference Costa and Santesteban2004; Costa, Santesteban & Ivanova, Reference Costa, Santesteban and Ivanova2006; Declerck, Koch & Philipp, Reference Declerck, Koch and Philipp2012; Ma, Li & Guo, Reference Ma, Li and Guo2016; Meuter & Allport, Reference Meuter and Allport1999). Moreover, the common pattern of switch costs is that they are larger when switching into the more dominant first language (L1) than into the less dominant second language (L2). The IC Model provides an account for these costs and their asymmetry across languages in terms of reactive inhibition exerted on the non-target language (Green, Reference Green1998). Specifically, on the switch trial, the target language in the current trial is the non-target language that needed to be inhibited in the previous trial. The reactivation of this language or the resolution of the persisting inhibition requires extra cognitive resources, leading to switch costs (for other explanations, such as the Persisting Activation Hypothesis and the L1-Repeat-Benefit Hypothesis, see Baus et al., Reference Baus, Branzi, Costa and Schwieter2015; Bobb & Wodniecka, Reference Bobb and Wodniecka2013; Declerck & Philipp, Reference Declerck and Philipp2015; Philipp, Gade & Koch, Reference Philipp, Gade and Koch2007; Verhoef, Roelofs & Chwilla, Reference Verhoef, Roelofs and Chwilla2009, Reference Verhoef, Roelofs and Chwilla2010).

Previous ERP studies using the language switching paradigm have shown that switch trials elicit a larger fronto-central N2 (a negative-going ERP component which peaks at approximately 200–350 ms post-stimulus) than non-switch trials (e.g., Jackson, Swainson, Cunnington & Jackson, Reference Jackson, Swainson, Cunnington and Jackson2001). Given that the fronto-central N2 has been considered to reflect general cognitive control (for a review, see Folstein & Van Petten, Reference Folstein and Van Petten2008), the N2 switch effect in the language switching task suggests that cognitive control plays a role in bilingual word production. Furthermore, by presenting the cue ahead of the stimulus to separate the language task schema competition phase and the lexical selection phase, Kang, Ma and Guo (Reference Kang, Ma and Guo2018) found a robust N2 switch effect in stimulus-locked ERPs, indicating that inhibitory control is exercised in the lexical selection phase (see also Chang, Xie, Li, Wang & Liu, Reference Chang, Xie, Li, Wang and Liu2016; Guo, Ma & Liu, Reference Guo, Ma and Liu2013; but see Verhoef et al., Reference Verhoef, Roelofs and Chwilla2009, Reference Verhoef, Roelofs and Chwilla2010).

We were interested in whether the three components of executive functions would be related to the language control processes in bilingual word production, as reflected by the language switch effects in behavioral (i.e., the difference between switch and non-switch trials in response times) and ERP data (i.e., the amplitude difference between switch and non-switch trials in stimulus-locked ERPs).

2 Material and methods

2.1 Participants

Fifty-Five Chinese–English bilinguals participated in the present study. All participants were right-handed with normal or corrected to normal vision. None of them reported having neurological or psychological disorders. One participant's data were eliminated due to technical issues during data collection. Another two participants pressed the wrong key(s) in the switching task and the two cases with missing data were eliminated from further analysis. Therefore, the final sample consisted of 52 participants (30 females, mean age = 22.63 yrs, SD = 2.41, ranging from 19 to 28 yrs). They were all native Chinese speakers, and had started learning English at around age 11 (Mean = 10.52, SD = 2.15, ranging from 3 to 14). They all passed the College English Test-Band 4 (CET-4, total score is 710), a mandatory English proficiency test for college students in Mainland China, with a mean score of 527 (SD = 49.25). A paired-samples t-test on participants’ self-ratings of their first language (L1) and second language (L2) proficiency (combined listening, speaking, reading and writing) on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 = not proficient, 10 = highly proficient) showed that they were significantly more proficient in their L1 (Mean = 7.75, SD = 1.21) than L2 (Mean = 5.05, SD = 1.33), t(51) = 15.22, p < .001, suggesting that they were unbalanced Chinese–English bilinguals dominant in L1 but relatively proficient in English as L2. Before the formal experiment, all participants signed the informed consent forms.

2.2 Materials

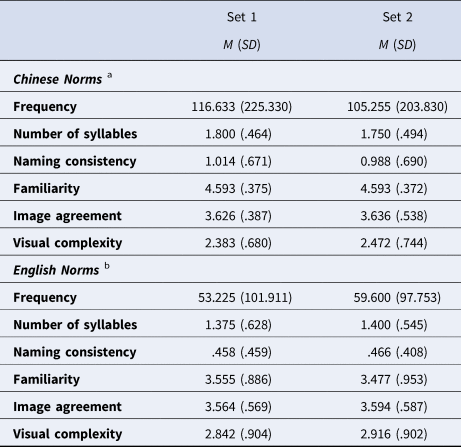

The stimuli of the language switching task were 88 black-and-white line drawings selected from Snodgrass and Vanderwart (Reference Snodgrass and Vanderwart1980), including 8 practice or filler pictures and two well-matched sets of 40 pictures (see Table 1). The two sets were counterbalanced across participants. In other words, for each participant, there were only 40 critical pictures.

Table 1. The Properties of the Two Sets of Pictures.

Note: a, data from Zhang and Yang (Reference Zhang and Yang2003); b, data from Snodgrass and Vanderwart (Reference Snodgrass and Vanderwart1980); Paired-sample t tests showed no significant difference in any properties between the two picture sets, ps > .562.

2.3 Procedure

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Imaging Center for Brain Research of Beijing Normal University. Participants were required to first complete a cued language switching task, during which both their behavioral data and EEG data were collected. Then, they were required to take three executive function tasks, including the flanker task, the switching task and the n-back task, to tap into their inhibiting, shifting and updating functions respectively. Only behavioral data were collected for these three tasks. The order of the three executive function tasks was counterbalanced across participants.

The cued language switching task

To achieve high consistency in their naming responses, participants were first familiarized with the picture names in both Chinese and English. Then, they were presented 8 practice trials to familiarize them with the procedure before the formal experiment.

The practice and formal experiment followed the same procedure: each trial started with a fixation point for 500 ms. After the screen was blank for 300 ms, a blue or red frame appeared as a cue for the target language to be used. 800 ms later, a picture appeared within the frame for 1000 ms. Participants were required to name the picture in the target language as quickly and accurately as possible. After the frame and the picture disappeared, a blank screen was presented for 1200–1600 ms randomly prior to the next trial. The response made within 2200 ms after the onset of the picture were recorded by a microphone and a recorder. All stimuli were presented in the center of the screen. The color-language mapping was counterbalanced across participants. It is noteworthy that a long cue-to-stimulus interval of 800 ms was used, which allowed the examination of both cue-locked and stimulus-locked ERPs reflecting respectively the language task schema competition phase and the lexical selection phase proposed in the IC model (Green, Reference Green1998).

The whole task contained eight blocks. Each block consisted of one filler trial and 40 critical trials. All trials were presented pseudo-randomly to make the number of trials for each condition equal. To make sure each picture was present in all four conditions, the 40 pictures (set 1 or 2) were randomly divided into 4 subsets and then assigned to different conditions in different blocks based on the Latin square design. The whole task lasted for 25 to 30 minutes.

The flanker task

An arrow-flanker paradigm was used in the present study. Participants were asked to press the corresponding key based on the pointing of the center arrow (e.g., if the center arrow pointed to the left, the correct response was to press the key on the left), which was flanked by two stimuli on both sides in line. The four flanker stimuli could be arrows pointing in the same direction as the center one (the congruent condition), arrows pointing opposite to the center one (the incongruent condition), or lines without any pointing (the neutral condition).

Each trial started with a central fixation (“+”) for 300 ms, followed by a blank buffer for 200 ms. Then, the five stimuli were presented in the center of the screen for up to 1000 ms. Participants were instructed to judge the direction of the center arrow and press the corresponding key as quickly and accurately as possible. The stimuli disappeared once any response was made. Then, a blank screen was presented for 500 ms before the next trial. Responses made within 1500 ms after the onset of the stimuli were recorded.

The flanker task included 4 blocks, presented in a randomized order. Each block consisted of 90 trials, presented in a pseudorandom order. Trials of the three conditions were proportional in each block. The dependent measure was the difference in response time between the incongruent and the congruent condition (i.e., the flanker effect in RT).

The switching task

In the switching task, participants were required to switch between judging the parity (odd or even) and the magnitude (larger or smaller than 5) of digits (1–4 and 6–9) based on a geometric cue (a square or a rhombus) presented prior to the digit. Each trial started with a central fixation (“+”) for 300 ms, which was followed by a blank buffer for 200 ms. Next, the geometric cue appeared at the center of the screen for 500 ms. Then, a single digit appeared at the center of the geometric cue. Participants were instructed to make a judgment about the parity or the magnitude of the digit as indicated by the cue as quickly and accurately as possible. The digit and the cue disappeared once any response was made or automatically after 1000 ms. After that, a blank screen of 1000 ms was presented prior to the next trial. Responses made within 2000 ms following the digit onset were recorded.

The task included 6 blocks. The first two were single-task blocks, one for parity judgment and one for magnitude judgment. They were designed for familiarizing participants with the cue-task mapping and the response-key mapping. The order of the two blocks was randomized. Each single-task block included 40 trials. The final four blocks were mixed-task blocks presented in random order. Each mixed-task block consisted of 41 trials with the first one as filler that were excluded from analyses. The two types of cues were presented pseudo-randomly to make the two tasks as well as the two conditions (task-switch or task-non-switch) proportional. The cue-task mapping and the response-key mapping were counterbalanced among participants. Before the first mixed-task block, participants were given 8 trials to practice switching between the two judgment tasks. The dependent measure we considered here was the task switch costs (the difference between task-switch and task-non-switch trials in mixed-task blocks) in RT.

The n-back task

The numerical n-back task in the present study included two memory load levels, 2 and 3, requiring participants to determine whether the digit in the current trial was the same as the one in 2-back or 3-back trials respectively. Ten digits from 0 to 9 were used as stimuli. There were 12 blocks in total, with the first 6 blocks being 2-back ones and the last 6 ones being 3-back ones. Within the 6 blocks with the same memory load, the order was randomized.

Each block included 20 trials, five of which were targets (25%). The order of the trials was pseudorandom. Each trial began with a digit presented at the center of the screen for 500 ms, followed by a blank buffer for 2000 ms, leading to an interstimulus interval (ISI) of 2500 ms. Responses made within 2000 ms after the digit onset were recorded. The dependent measures we were interested in here were two aggregative indices, the discrimination index (d L) and the bias index (C L) (cf. Kane et al., Reference Kane, Conway, Miura and Colflesh2007 for calculation) obtained from the 3-back blocks.

2.4 EEG data recording and analysis

While participants were taking the cued language switching task, their EEGs were recorded from a 32-channel Quik Cap (NeuroScan Inc.). The horizontal electro-oculograms (EOGs) and the vertical EOGs were recorded by two electrodes placed at the external canthus of each eye and by two electrodes attached around 1 cm above and below the left eye, respectively. The impedances of all electrodes were kept below 5 KiloOhms. The EEGs obtained from all electrodes were online referenced to the right mastoid, sampled at a rate of 500 Hz and filtered with a .05–100 Hz band-pass.

During the data pre-processing offline, the trials with language error (naming in the wrong language) and naming error (naming in the right language but with the wrong word) were first removed. Then, the trials affected by ocular artifacts were corrected by the algorithm embedded in the Neuroscan analysis software (Gratton, Coles & Donchin, Reference Gratton, Coles and Donchin1983). The EEGs obtained from all electrodes were re-referenced to the average of both mastoids, filtered at a low-pass of 30 Hz (24 dB/Oct), and segmented from 100 ms before to 600 ms after stimulus onset, with data in the first 100 ms as baseline. The epochs with voltages exceeding ± 100 μV (2.76%) were rejected to eliminate data contaminated by eye blinks, eye movements and muscle movements. For all participants, more than 75% trials were left after preprocessing.

The time windows for the ERP components of interest were first determined by visual inspection of the stimulus-locked (see Figure 1) grand average waveforms. The critical latency range for each ERP component was then determined by performing 2 (Language) × 2 (Type of Trial) × 9 (Electrode Site) repeated-measures ANOVAs on adjacent 20-ms time windows over the electrode sites, F3, FZ, F4, FC3, FCZ, FC4, C3, CZ and C4, where the N2 switch effect has been reported repeatedly (see Guo et al., Reference Guo, Ma and Liu2013; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Ma and Guo2018). The onset and offset for each stimulus-locked component were defined as the onset of the first 2 consecutive significant ANOVAs and the offset of the last 2 consecutive significant ANOVAs respectively, revealing the N2 occurred 210–250 ms and 250–370 ms (the main effects of Type of Trial and the interactions between Type of Trial and Electrode Site being significant, ps < .05, see Table 1S), and the N400-like occurred 410–510 ms post stimulus onset (the main effect of Type of Trial, the interactions between Type of Trial and Electrode Site, the main effect of Language, and the interaction between Language and Electrode Site being significant, ps < .05, see Table 1S). The mean amplitudes within the above-mentioned critical time windows for each participant were extracted from the nine fronto-central electrode sites.

Fig. 1. The grand average waveforms for non-switch trials (solid line) and switch (dash line) in L1 (grey) and L2 (black) in stimulus phase. All conditions elicited a P1/N1 complex, a P2, followed by an N2 complex and an N400-like.

2.5 Linear mixed effects model analyses

We used R (R Core Team, 2017) and lmeTest (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff & Christensen, Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017) to perform linear mixed effects model analyses of the potential predictions of the three executive functions to language control processes. Specifically, the inhibition component of executive functions was measured by the flanker effect in RTs, the shifting component was indexed by the task switch costs in RTs, and the updating component was assessed by d L and C L in 3-back task. In addition, the language control processes were measured by RTs, the stimulus-locked N2 amplitude and N400-like amplitude (averaged across the 9 fronto-central electrode sites mentioned earlier).

As fixed effects, we entered language, type of trial (switch or non-switch), flanker effect, task switch costs, d L and C L into the model. As random effects, we had intercepts for subjects and items, as well as by-subject and by-item random slopes for type of trial (Model 1). Based on our prediction that, among the three executive functions, the inhibition component might be most closely related to language control processes, we first excluded the interactions involving the d L and C L (Model 2) and then further excluded interactions involving the task switch costs (Model 3) from the full model aforementioned (Model 1)Footnote 1, and compared the models through likelihood ratio tests to find out the optimal model. Figure 2 shows the construction of the models.

Fig. 2. The construction of the three models in the linear mixed effect model analyses. The fixed effects marked in purple were related to the potential predictions of d L and C L to the language switch costs (language: type of trial), the switch costs (type of trial) and the language effect (language), which were further excluded in Model 2 and 3. The fixed effects marked in green were related to the potential predictions of task switch costs to the language switch costs, the switch costs and the language effect, which were further excluded in Model 3. The fixed effects and random effects not marked were same in the three models.

Note, DV (dependent variable) could be RTs, stimulus-locked N2 mean amplitude in 210–250 ms and 250–370 ms, and stimulus-locked N400-like mean amplitude in 410–510 ms. To reduce numerical instability for estimation associated with multicollinearity, especially when examining interaction effects, the four consecutive variables indicating the executive functions were centered (Afshartous & Preston, Reference Afshartous and Preston2011; Robinson & Schumacker, Reference Robinson and Schumacker2009). The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of no fixed effects in any models exceeded 4, indicating that there is no sign of severe multicollinearity (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2007). Visual inspection of residual plots did not reveal any obvious deviations from homoscedasticity or normality.Footnote 2

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics of the three executive function tasks

For the flanker task, incorrect RTs (2.54%) were first eliminated. Then, RTs 2.5 standard deviations slower or faster than each participant's mean RT (2.01%) were further excluded. For the switching task, incorrect responses as well as the responses directly following the incorrect ones in mixed-task blocks were first excluded (15.67%). Then, RTs 2.5 standard deviations slower or faster than each participant's mean RT (2.35%) were further excluded. For the n-back task, the first three trials in each 3-back block were eliminated as fillers. Then, participants’ responses were recoded based on the type of the trial. For the targets, the correct responses were recoded as “Hit”, while the incorrect ones were “Miss”. For the nontargets, the correct responses were recoded as “Correct reject”, while the incorrect ones were “False alarm”. The Hit rates and the False alarm rates were calculated and adjusted by .01 if equal to either 0 or 1 for further calculation of the d L and the C L (cf. Kane et al., Reference Kane, Conway, Miura and Colflesh2007).

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics for the 4 variables, including the flanker effect in RTs, the task switch costs in RTsFootnote 3, the d L and the C L obtained from the 3-back task, as well as the correlations between these measures. Notably, the negative correlation between the task switch costs and the d L was significant, r = -.341, p = .013. To calculate reliability estimates for the three executive function tasks, we divided the critical blocks (all 4 blocks in the flanker task, the 4 mixed-task blocks in the switching task, and the six 3-back blocks in the n-back task) into two subsets (odd-even) and calculated two subscales for the flanker effect, the task switch costs, the d L and the C L. Then we calculated Cronbach's alpha from the two subscales for each measure (cf. Kane et al., Reference Kane, Conway, Miura and Colflesh2007).

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of the Four Independent Variables and the Pearson Correlations between Them.

3.2 Behavioral results of the language switching task

For the cued language switching task, incorrect RTs (6.26%, including language errors and naming errors) were first excluded. Then, RTs 2.5 standard deviations slower or faster than each participant's mean RT (1.99%) were further excluded. Figure 3 shows the mean RTs and the mean error rates (ERs) across the four conditions.

Fig. 3. Mean response times (RTs, panel A) and mean error rates (ERs, panel B.) of non-switch and switch trials in L1 and L2. Error bars show one standard error.

With RTs as the DV, the comparison between Model 1 and 2 showed that the exclusion of the interactions involving d L and C L did not significantly change model fit, χ2 (6) = 6.349, p = .385. Further exclusion of the interactions involving task switch costs did not change model fit either, χ2 (3) = 5.146, p = .161, resulting from the comparison between Models 2 and 3. In other word, Model 3, with the smallest AIC, was the optimal model (see Table 3).

Table 3. Linear Mixed Effects Model of RTs in Language Switching with Flanker Effect as a Further Predictor.

Note: ª covariates; *** p < .001, * p < .05

Linear mixed effects model analyses showed that naming in switch trials was significantly slower than that in non-switch trials, as indicated by a significant main effect of type of trial. However, the interaction between language and type of trial was not significant, revealing symmetrical switch costs of the two languages. Moreover, the flanker effect did not predict the switch costs, as reflected by the non-significant interaction between type of trial and flanker effect.

3.3 ERP results of stimulus-locked N2

For mean amplitudes in 210–250 ms time window

The comparison between Models 1, 2 and 3 with stimulus-locked N2 mean amplitude in 210–250 ms time window as the DV revealed no significant differences in model fit between Model 3 and 2, χ2 (3) = 5.814, p = .121, nor between Model 2 and 1, χ2 (6) = 7.566, p = .272, revealing that inclusion of the interactions involving the task switch costs and further inclusion of the interactions involving the d L and C L would not improve the model fit. We report the fixed effects of Model 3 (see Table 4), since it was the simplest model with the smallest AIC.

Table 4. Linear Mixed Effects Models of Stimulus-locked ERPs in Language Switching with Flanker Effect as a Further Predictor.

Note: ª covariates; *** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05

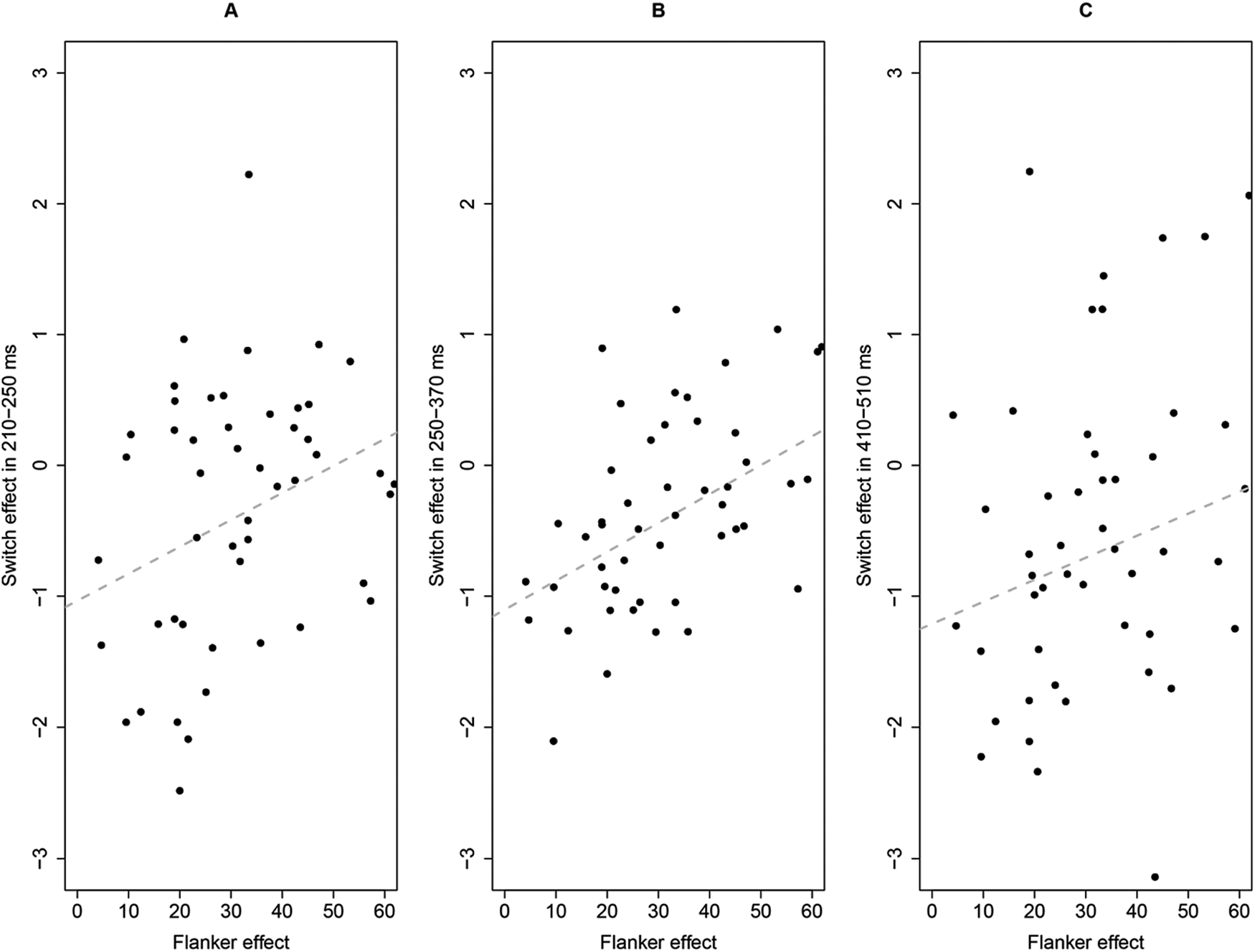

Linear mixed effects model analysis showed that naming in switch trials elicited a larger N2 than naming in non-switch trials, as indicated by the significant main effect of type of trial. However, the interaction between language and type of trial was not significant, indicating symmetrical switch effects of the two languages. Critically, the flanker effect could significantly predict the N2 switch effect, which was reflected by the significant interaction between type of trial and flanker effect. As shown in Figure 4A, smaller flanker effect was correlated with larger difference in N2 amplitude between naming in switch trials and non-switch trials.

Fig. 4. Relationship between flanker effect (in ms) and stimulus-locked switch effect (i.e., switch minus non-switch, in μV) in 210–250 ms (A), in 250–370 ms (B) and in 410–510 ms (C).

For mean amplitudes in 250–370 ms time window

The results in 250–370 ms time window were similar with that in 210–250 ms time window. The comparison between Models 1, 2 and 3 with stimulus-locked N2 mean amplitude in 250–370 ms as the DV revealed no significant differences in model fit between Model 3 and 2, χ2 (3) = 1.233, p = .745, nor between Model 2 and 1, χ2 (6) = 5.496, p = .482, revealing that inclusion of the interactions involving the task switch costs and further inclusion of the interactions involving the d L and C L would not improve the model fit. We report the fixed effects of Model 3 (see Table 4), since it was the simplest model with the smallest AIC.

Linear mixed effects model analysis showed that naming in switch trials elicited a larger N2 than naming in non-switch trials, as indicated by the significant main effect of type of trial. The interaction between language and type of trial was not significant, indicating symmetrical switch effects of the two languages. Critically, the flanker effect could significantly predict the N2 switch effect, which was reflected by the significant interaction between type of trial and flanker effect. As shown in Figure 4B, smaller flanker effect was correlated with larger difference in N2 amplitude in 250–370 ms time window between naming in switch trials and non-switch trials.

3.4 ERP results of stimulus-locked N400-like

The comparison between Models 1, 2 and 3 with stimulus-locked N400-like mean amplitude as the DV revealed no significant differences in model fit between Model 3 and 2, χ2 (3) = 3.556, p = .314, nor between Model 2 and 1, χ2 (6) = 8.022, p = .237, revealing that inclusion of the interactions involving the task switch costs and further inclusion of the interactions involving the d L and C L would not improve the model fit. We report the fixed effects of Model 3 (see Table 4), since it was the simplest model with the smallest AIC.

Linear mixed effects model analysis showed that naming in L1 elicited a larger N400-like than naming in L2, as indicated by the significant main effect of language. Naming in switch trials elicited a larger N400-like than naming in non-switch trials, as indicated by the significant main effect of type of trial. The interaction between language and type of trial was not significant, indicating symmetrical switch effects of the two languages. Notably, the flanker effect did not predict the switch effect in this component, as indicated by the nonsignificant interaction between type of trial and flanker effect (see Figure 4C).

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the potential predictions of three components of executive functions on language control mechanisms with unbalanced Chinese–English bilinguals. To examine each individual's general executive functions of inhibiting, shifting and updating, we adopted three nonlinguistic tasks, including the flanker task, the switching task and the n-back task. To investigate bilinguals’ language control processes, we used the cued language switching task and focused mainly on the lexical selection phase (Green, Reference Green1998), where reactive inhibition has been proven to be exist (e.g., Declerck, Koch & Philipp, Reference Declerck, Koch and Philipp2015; Declerck & Philipp, Reference Declerck and Philipp2017; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Ma and Liu2013; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Ma and Guo2018; Kleinman & Gollan, Reference Kleinman and Gollan2016). Linear mixed effects modeling analyses showed that compared to non-switch trials, picture naming on switch trials was slower and elicited larger N2 and N400-like in stimulus-locked ERPs. Critically, the flanker effect in RTs, reflecting domain-general inhibition, significantly predicted the variability of the stimulus-locked N2 switch effect. However, the flanker effect did not predict the variability of language switch costs in RTs or the stimulus-locked N400-like switch effect. Likewise, the task switch costs indicating the domain-general shifting and the d L and the C L obtained from the 3-back task indexing domain-general updating did not predict the variability of the language switch effects in RTs or stimulus-locked ERP effects.

4.1 Language control mechanisms

Replicating past research, the behavioral results showed that picture naming on switch trials was slower than that on non-switch trials, resulting in robust switch costs. However, there was no asymmetry between the switch costs in the two languages, a pattern reported in some studies with unbalanced bilinguals and/or less proficient bilinguals (e.g., Costa & Santesteban, Reference Costa and Santesteban2004; Meuter & Allport, Reference Meuter and Allport1999). Interestingly, asymmetrical switch costs have not been consistently reported in unbalanced bilinguals (e.g., Christoffels, Firk & Schiller, Reference Christoffels, Firk and Schiller2007). Some studies (Declerck et al., Reference Declerck, Koch and Philipp2012; Declerck et al., Reference Declerck, Koch and Philipp2015; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Ma and Liu2013; Verhoef et al., Reference Verhoef, Roelofs and Chwilla2009, Reference Verhoef, Roelofs and Chwilla2010) have suggested that a long CSI and/or a variable response-to-stimulus interval (RSI) reduces the magnitude of language switch costs and eliminates the asymmetry of switch costs in unbalanced bilinguals. As the present study used a long CSI of 800 ms and variable RSIs of 1600 ms and longer, we speculate that the absence of asymmetrical switch costs observed may potentially be understood in this way.

The ERP results revealed that switch trials elicited a larger stimulus-locked N2 than non-switch trials in both the 210–250 ms and the 250–370 ms time window. These results were in line with the findings of previous studies examining the loci of inhibition during bilingual word production (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Xie, Li, Wang and Liu2016; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Ma and Liu2013), and confirmed that bilinguals need to exert inhibition on the non-target language in the lexical selection phase. More interestingly, this effect lasted until the N400-like time window in stimulus-locked ERPs. Specifically, switch trials induced a more negative N400-like component, as compared to the non-switch trials. As a larger N400 has been widely associated with more difficulties in processing meaning (e.g., Blackford, Holcomb, Grainger & Kuperberg, Reference Blackford, Holcomb, Grainger and Kuperberg2012; Rose, Aristei, Melinger & Abdel Rahman, Reference Rose, Aristei, Melinger and Abdel Rahman2018), the N400-like effect we observed suggests that it was more difficult for bilinguals to retrieve word meaning on switch trials during picture naming. The extra difficulty could be ascribed to the inhibition of the lexical items in the non-target language in the switch trials.

As stimulus-locked ERPs are believed to reflect the processes during the lemma selection phase in the IC model, the N2 effect in stimulus-locked ERPs has been taken as reactive inhibition of a lemma in the non-target language by the target language schema (e.g., Guo et al., Reference Guo, Ma and Liu2013; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Ma and Guo2018). Thus, we speculate that the following N400-like effect is likely to indicate inhibition of the semantics of a lemma in the nontarget-language after lemma activation, suggesting that bilinguals need to inhibit the non-target language during the lexical meaning retrieval phase of word production. Taken together, our findings provide support for the IC model's (Green, Reference Green1998) assumption that bilinguals need to exert language control over the lemma selection phase of speech planning.

4.2 Contributions from domain-general inhibition to language control

The analyses of mixed effects models with the stimulus-locked N2 mean amplitude as the dependent variable revealed that only the flanker effect robustly predicted the N2 switch effect in the lexical selection phase. However, the stimulus-locked N400-like switch effect was not predicted by the flanker effect.

The flanker effect reflects interference suppression of the inhibitory control mechanism (Brydges, Clunies-Ross, Clohessy, Lo, Nguyen, Rousset, Whitelaw, Yeap & Fox, Reference Brydges, Clunies-Ross, Clohessy, Lo, Nguyen, Rousset, Whitelaw, Yeap and Fox2012; Bunge et al., Reference Bunge, Dudukovic, Thomason, Vaidya and Gabrieli2002). Specifically, in the incongruent condition of the flanker task, the response indicated by the flankers was different from that indicated by the target, leading to the response conflict. To resolve this conflict, interference from the flankers may be suppressed, prolonging the response time and resulting in a flanker effect. Thus, the flanker effect has been widely used to reflect individual's interference suppression ability (Bunge et al., Reference Bunge, Dudukovic, Thomason, Vaidya and Gabrieli2002; Luk, Anderson, Craik, Grady & Bialystok, Reference Luk, Anderson, Craik, Grady and Bialystok2010).

Similarly, in bilingual word production, the inhibition on the non-target language has been proposed to involve suppressing interference induced by cross-language interaction (e.g., Green, Reference Green1998). Specifically, on the switch trials, the non-target language in the current trial is highly activated in the previous trial as the target language. Its persisting activation is hypothesized to cause strong interference to the lexical selection in the current trial and thus require robust interference monitoring and suppression. On the contrary, in the non-switch condition, the non-target language is activated to a relatively weak extent in two consecutive trials. Thus, compared with the non-switch trials, interference suppression on the non-target language should be stronger in the switch trials.

Indeed, our data showed that switch trials elicited a larger N2 component than non-switch trials during the lexical selection phase, indicating stronger interference suppression in switch trials. More critically, the results revealed that the smaller the flanker effect was, the larger the difference in stimulus-locked N2 between switch and non-switch trials was. In other words, the better individuals’ general interference suppression was, the stronger the inhibition exerted on the lexical items in the non-target language during bilingual word production was. These results suggest that the interference suppression component of executive functions predicts the intensity of inhibition exerted on the lexical items in non-target language.

The current pattern of results partly lines up with the finding in Linck et al.'s (Reference Linck, Schwieter and Sunderman2012) study on the relationship between general inhibitory control and language control. In Linck et al.'s study, English–French–Spanish trilinguals performed a language switching task and a Simon task. Results showed that trilinguals with smaller Simon effect exhibited smaller switch costs when switching from the weak L2 or L3 into the dominant L1. Based on their findings, Linck et al. (Reference Linck, Schwieter and Sunderman2012) speculated that better general inhibitory control facilitates the efficiency of exerting inhibition during bilingual language control. Likewise, Struys, Woumans, Nour, Kepinska and Van den Noort (Reference Struys, Woumans, Nour, Kepinska and Van den Noort2019) reported that RTs in the Simon task were correlated with the L2 switch costs in a language comprehension task, during which Dutch–French bilinguals judged the animacy of the word presented in either language. In line with these patterns, the present finding showed that better inhibition is associated with a larger amount of inhibition exerted on the non-target language during bilingual language control, providing complementary evidence for the relationship between the interference suppression component of executive functions and the bilingual language control mechanisms from a different perspective.

It is worth noting that our behavioral data are congruent with Jylkkä et al.'s (Reference Jylkkä, Lehtonen, Lindholm, Kuusakoski and Laine2018) finding that the flanker effect did not correlate with language switch costs. However, the ERP data we have reported showed a reliable correlation. The discrepancy between behavioural measures and ERP data further suggests that the behavioral data reflect an aggregation of different cognitive processes, while the time-sensitive ERPs allow dissociating various stages of processing in specific components (e.g., Guo et al., Reference Guo, Misra, Tam and Kroll2012; Kousaie & Phillips, Reference Kousaie and Phillips2012b; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Chen, Guo and Kroll2017; van Hell & Kroll, Reference Van Hell, Kroll, Altarriba and Isurin2013). In addition, our behavioral data contrasted with Linck et al.'s (Reference Linck, Schwieter and Sunderman2012) study, which shows a significant contribution of the inhibitory control as reflected by the Simon effect to language switch costs. One possibility is that the flanker effect and the Simon effect may tap into different underlying mechanisms of inhibitory control (e.g., Mansfield, van der Molen, Falkenstein & van Boxtel, Reference Mansfield, van der Molen, Falkenstein and van Boxtel2013), or they may differ in terms of the temporal distance between the activation of task-relevant or -irrelevant response (e.g., Hübner & Töbel, Reference Hübner and Töbel2019), resulting in different effects. Nonetheless, even though both studies employed the Simon task, contrasting results were reported by Linck et al. (Reference Linck, Schwieter and Sunderman2012) and Jylkkä et al. (Reference Jylkkä, Lehtonen, Lindholm, Kuusakoski and Laine2018). Taken together, the predicting effect of the inhibitory control on behavioral language switch costs still remains equivocal thus needs to be further explored.

Unlike the N2 effect, the N400-like effect in the stimulus-locked phase was not predicted by the flanker effect. We speculate that the divergent patterns suggest a distinction between domain-general and language-specific control components and the different time courses they are employed in the lexical selection phase during bilingual word production. Specifically, at an earlier stage of lexical selection, domain-general inhibition may be required on lexical items of the non-target language, as indexed by the predictive effect of the flanker effect on the N2 effect. In contrast, at a later stage of lexical selection, language-specific inhibitory control may be executed, as indicated by the finding that the flanker effect did not predict the N400-like effect. In other words, two types of inhibitory control may be exerted throughout the lexical selection phase during bilingual language production, with domain general inhibition preceding language specific inhibition. It is also possible that the N400-like effect may indicate extra effort to overcome persistent inhibition on switch trials. As the flanker effect does not reflect persistent inhibition in adjacent trials, it did not predict the N400-like effect.

4.3 Role of general shifting and updating in language control

Model comparisons through likelihood ratio tests showed that neither the inclusion of task switch costs nor further inclusion of the d L and C L in the 3-back task improve model fit significantly, regardless of the dependent variable (RTs, stimulus-locked N2 or N400-like amplitude).

Previous studies have examined whether executive functions and bilingual language control overlap with each other by comparing task switch costs in the nonlinguistic switching paradigm and language switch costs in the language switching task. Results have shown that the two types of switch costs do not always correlate with each other. For example, Calabria, Hernández, Branzi and Costa (Reference Calabria, Hernández, Branzi and Costa2012) did not find a correlation between these two indices of switching. In addition, highly proficient bilinguals showed symmetrical switch costs in language switching task but asymmetrical switch costs in a non-language switching task, a divergence that Calabria et al. (Reference Calabria, Hernández, Branzi and Costa2012) took as evidence for the claim that language control was not subordinate to general executive control (see also Calabria, Branzi, Marne, Hernández & Costa, Reference Calabria, Branzi, Marne, Hernández and Costa2015; Weissberger, Wierenga, Bondi & Gollan, Reference Weissberger, Wierenga, Bondi and Gollan2012). In contrast, with more similarity in the language switching task and the switching task, Declerck, Grainger, Koch and Philipp (Reference Declerck, Grainger, Koch and Philipp2017) did observe significant positive correlation between language and task switch costs. Interestingly, Prior and Gollan (Reference Prior and Gollan2013) reported no transfer effect of switch costs in any direction (from language to task or from task to language), but Timmer, Calabria and Costa (Reference Timmer, Calabria and Costa2019) found transfer effect from linguistic switching training to nonlinguistic domain despite the fact that there was no significant correlation between these two indices. These findings indicate that the mechanisms underlying language switch costs and non-language switch costs may not entirely overlap.

Although some previous studies suggest that bilingualism confers benefit to working memory (older adults, Bialystok et al., Reference Bialystok, Craik, Klein and Viswanathan2004; children, Morales et al., Reference Morales, Calvo and Bialystok2013; but see Bialystok et al., Reference Bialystok, Craik and Luk2008) and makes up for weakness in working memory in children with low socioeconomic status (Blom, Küntay, Messer, Verhagen & Leseman, Reference Blom, Küntay, Messer, Verhagen and Leseman2014), few past studies have directly examined the contribution of working memory to bilingual language control. The present study attempted to investigate whether updating functions contribute to language control processes, but failed to find any significant results. One possibility is that updating plays a limited role in control process of bilingual production at the word level. Future studies may examine the role of working memory in language control of bilingual production at the sentence or discourse level.

Taken together, our results indicate that general shifting and updating functions make little contribution to bilingual language control processes, at least when stimulus-locked N2 and N400-like effects were taken as the indicators of control process. This is partly congruent with the Von Bastian et al.'s (Reference Von Bastian, Souza and Gade2016) finding that individuals did not benefit from a high level of bilingualism in cognitive tasks involving shifting and updatingFootnote 4. To further explore the prediction of shifting and updating to bilingual language control, future studies could attempt to use other executive function tasks, behavioral or ERP indices.

5 Conclusions

The present study showed that inhibition alone predicted the intensity of language control exerted on the non-target language during bilingual word production. Specifically, stronger interference suppression ability, as reflected by a smaller flanker effect, facilitates inhibition on the non-target language, as indicated by a larger N2 but not N400-like switch effect in the stimulus-locked ERPs. Consistent with the IC model (Green, Reference Green1998), these results suggest that inhibition plays a crucial role in bilingual language production, particularly during the language schema competition stage. Specifically, the target language schema inhibits the non-target language schema to ensure production in the intended language. In addition, the present findings indicate that bilingual language control only partially overlaps with executive functions (Valian, Reference Valian2015). This is also in line with the assumptions of the adaptive control hypothesis (Green & Abutalebi, Reference Green and Abutalebi2013), according to which language control may involve a separate system that is recruited for certain nonlinguistic tasks. As discussed earlier, no such predictive effect was observed in the behavioral data, which suggests that ERPs provide a more sensitive measure to investigate bilingual language processing. Notably, the three executive functions were measured in three single tasks respectively. We acknowledge that the three tasks may involve other cognitive processes than the three corresponding executive functions (i.e., the task impurity issue, see Miyake et al., Reference Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter and Wager2000). To obtain more precise measures for different components of the general executive functions, future studies could take analyses based on latent variables into consideration, which requires recruiting a large number of participants to complete multiple tasks (Friedman, Reference Friedman2016). Finally, it is worth noting that studies conducted at one point in time still have limitations in figuring out the interaction between general executive functions and language control processes. Future studies might consider training (e.g., Liu et al., Reference Liu, Liang, Dunlap, Fan and Chen2016b; Timmer et al., Reference Timmer, Calabria and Costa2019; see Festman, Rodriguez-Fornells & Münte, Reference Festman, Rodriguez-Fornells and Münte2010 for related discussion) and longitudinal approaches (see Gross & Kaushanskaya, Reference Gross and Kaushanskaya2018 for similar consideration).

Supplementary Material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728920000085.

Acknowledgements

The first three authors made equal contribution to the manuscript. The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31871097) to Taomei Guo, the National Key Basic Research Program of China (2014CB846102), the Interdiscipline Research Funds of Beijing Normal University, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2017XTCX04). The writing of this paper was supported in part by NIH Grant HD082796 and NSF Grants BCS-1535124 and OISE-1545900 to Judith F. Kroll and the Research Start-up Funds of Zhejiang Sci-Tech University (18062305-Y) and the Zhejiang Natural Science Foundation (LQ20C090009) to Chunyan Kang. The authors would like to thank Jie Lin, Junjie Wu, Di Lu, and Yongben Fu for data collection and Alex Titus for proofreading. The authors declared that there was no conflict of interest.