Introduction

This paper is concerned with the changing meaning of community in later life. It argues that the past emphasis upon communities of place (Heywood, Oldman and Means Reference Heywood, Oldman and Means2002) needs to be rebalanced or rethought in the light of emerging evidence for the growing engagement of older people in communities of interest linked to friendships, enthusiasms and their increased spending power (Rees-Jones et al. Reference Rees Jones, Hyde, Victor, Wiggins, Gilleard and Higgs2008).

The international context for the article is what Gullette (Reference Gullette2011: 11) calls the ‘current tsunami of alarmism’ about the implications of ageing populations (Bloom, Canning and Fink Reference Bloom, Canning and Fink2010). Part of this alarmism relates to the potential health and social care cost consequences of these population trends. This is leading governments increasingly to explore whether some of these costs can be offset by encouraging older people to ‘age well’ through maximising their involvement in a wide range of activities.

The different strands of these debates are drawn together in this paper. A reconceptualisation of community is argued for through a more sophisticated view of ‘place’ and ‘interest’ that avoids false dichotomies between the two and acknowledges the impact of social, economic and cultural change upon the lives of older people.

Defining ‘community’

For a concept that is so widely used, ‘community’ is notoriously difficult to define (Crow and Allan Reference Crow and Allan1994). The Cambridge Dictionary of American English opts for ‘all the people who live in a particular area or a group of people who are considered as a unit because of their shared interests, background, or nationality’. This reflects traditional sociological classifications that have focused on three elements of community: place, interest and identity. For example, Tönnies and Loomis (Reference Tönnies and Loomis1957) were some of the first sociologists to explore concepts of community. They coined the term ‘gemeinschaft’ to indicate social relations that are close-knit and intimate because they take place in a well-defined physical space, such as a rural village. They contrasted this to ‘gesellschaft’, a looser type of relationship based on associations that were less personal and intense. Both Tönnies and Loomis (Reference Tönnies and Loomis1957) and Durkheim (Reference Durkheim1964) saw community as fundamentally good, a source of social order, and suggested that the breakdown of community was responsible for various social ills.

In the late 1960s the concept of community fell out of academic favour, largely due to the work of Stacey (Reference Stacey1969) who focused instead on social networks. Similarly, Pahl (Reference Pahl1970) challenged traditional theories by suggesting that all communities were communities of the mind, an illusion that people adopt in order to create a feeling of control and autonomy over their lives. However, community soon re-emerged as a popular concept, with the focus increasingly on factors other than place as the key element. For example, Willmott (Reference Willmott1989) suggested that community is about people who share some element of identity or belonging. While this might relate to a physical place, he felt that increasingly it was to do with ethnicity, leisure interests or religious beliefs. At about the same time, Lee and Newby (Reference Lee and Newby1983) described three types of community that are similar to place-based, identity-based and interest-based communities. They called them locality (purely physical), local social systems (based on interaction) and communion (a shared sense of identity). Taking these theories further, a close-knit community can be seen as one in which the three dimensions (place, interest and identity) overlap extensively. More recently, Gilleard and Higgs (Reference Gilleard and Higgs2000) have suggested that communities based on shared interest are less exclusive than those based on identity and that the term ‘coalitions of interest’ is more appropriate than ‘communities of interest’.

In the next section we draw on the literature to explore in more detail how theories of community of place and community of interest have developed.

Community and place in later life

There is a long-standing literature that promotes the importance of ‘place’ as the key element in a sense of community, based on the broad theory that people develop a shared identity with others who live in the same physical area. Bernard et al. (Reference Bernard, Liddle, Bartlam, Scharf and Sim2011) discuss this concept in terms of shared identities that can become a major part of an individual's ‘self-definition’ and are often strongly linked to an older person's environment. Several writers have built on the concept of ‘gemeinschaft’ (Tönnies and Loomis Reference Tönnies and Loomis1957) to explore the characteristics of place in relation to community belonging. For example, Hargreaves (Reference Hargreaves2004) highlighted the importance of familiar natural and cultural features as a focus for individual and community identity, mediated by the role of layout in facilitating movements and social interactions. Drawing on a study in Scotland, he suggested that communities with a strong awareness of place display patterns of movement around specific landmarks that contribute towards the development of individual and social identities.

Many authors have argued that place is of particular importance to older people in terms of community belonging (Evans Reference Evans2009; Fried Reference Fried2000; Heywood, Oldman and Means Reference Heywood, Oldman and Means2002; Jorgensen and Stedman Reference Jorgensen and Stedman2001; Phillipson et al. Reference Phillipson, Bernard, Phillips and Ogg2001). The focus of these discussions has been on the importance of the local neighbourhood to older people, partly because the present generation of older people are more likely to have lived in the same community for most of their lives than future generations will have done (Phillipson et al. Reference Phillipson, Bernard, Phillips and Ogg2001). It is also the case that older people tend to spend more of their time in the local neighbourhood, particularly if they are retired. In their study of United Kingdom (UK) data, Kasarda and Janowitz (Reference Kasarda and Janowitz1974) found length of residence to be the most important factor in community attachment, followed by the number of local friends and relatives. The importance of the immediate neighbourhood to older people is supported by evidence that for people aged 65 and over neighbours tend to also be good friends, while for younger age groups local social interaction is more likely to take the form of casual ‘head nodding’ (Marsh Reference Marsh and Pilch2006). It is widely argued that living in the same place for a long time can promote greater place attachment. For example, Giuliani and Feldman (Reference Giuliani and Feldman1993) describe place attachment as a psychological investment in a place that develops over time and is encouraged by a range of factors. For example, the physical distinctiveness of a place, the continuity of a person's experience of that place and their level of self-esteem within that place can all contribute towards attachment. Rowles, a social geographer, identified three elements of place attachment: physical, social and autobiographical, all of which he felt are intimately related to a sense of self (Rowles Reference Rowles1983). He also suggested that length of residence is becoming less important as some older people use strategies to rapidly develop attachment and belonging after re-locating by re-making place. These strategies include replicating previous arrangements of furniture, developing tactics for connecting with new neighbours, careful placement of personal artefacts and psychological preparation.

The most personal embodiment of place is usually ‘home’, and several writers have highlighted the centrality of our housing to both place attachment and personal identity. Despres (Reference Despres1991) identified several psychological functions performed by a sense of home, including security and control, a reflection of personal values and a refuge from the outside world. In a study of housing decisions in later life, Clough et al. (Reference Clough, Leamy, Miller and Bright2004) focused on the importance of home as a venue for social interactions. This reflects a body of evidence to suggest that social interaction is the ‘glue’ that binds communities together. As early as 1969, sociologists such as Stacey (Reference Stacey1969) were focusing on the role of social networks in determining community belonging. Subsequently, commentators have theorised about different types of social network based on levels of physical and emotional closeness, and with different functions for the individual in terms of physical and mental wellbeing (Wenger Reference Wenger1995). More recently, studies have confirmed the continuing importance of social interaction as a powerful factor in the development of community attachment, even where those interactions are of a relatively fleeting and everyday nature (Robertson, Smyth and McIntosh Reference Robertson, Smyth and McIntosh2008).

There is evidence of the continuing importance of place in the development of community attachment among older people, particularly where family and friends live close by (Nash and Christie Reference Nash and Christie2003). Similarly, community membership based on well-defined and sometimes exclusive physical boundaries appears to be an important factor in many later-life housing choices (Evans Reference Evans2009). A range of recent UK and international policies for later life reflect this recognition of the importance of place for older people in terms of wellbeing and community belonging. In the UK, for example, the Government strategy for housing an ageing society (Department for Communities and Local Government 2008) highlights the concept of lifetime neighbourhoods that enable older people to go about their daily lives. Similarly, the Age-Friendly Cities initiative developed by the World Health Organisation (WHO 2006) promotes urban environments that are supportive of older people and enable them to be seen as a valuable resource for local communities rather than an economic burden, an approach that is now being rolled out to rural areas through such initiatives as the Age Friendly Communities Initiative in Manitoba, Canada (Menec et al. Reference Menec, Means, Keating, Parkhurst and Eales2011).

The emergence of a debate about communities of interest

It is important to recognise that communities of interest are not something that emerged ‘out of the blue’ at some early point in the Reagan/Thatcher years with their emphasis on marketisation, consumerism and individualisation. They are not a simple by-product of globalisation. In The Long History of Old Age, Thane's (Reference Thane2005) edited collection takes the reader right through from medieval times to the 20th century. She is able to illustrate the endless variety of lives lived over the centuries including the importance of the pursuit of hobbies, enthusiasms and civic activity by many, and especially by those with the greatest wealth and resources.

However, this long-established engagement of at least some older people with hobbies and enthusiasms has often been obscured by the extent of the emphasis upon the importance of communities of place to older people. The late 1980s began to see changes in this as a result of the impact of Laslett's (Reference Laslett1989) A Fresh Map of Life. The central thesis of this work was that developed economies suffered from a cultural lag of pessimism about the possibilities of later life. Old age was spoken about as if most older people had little to look forward to when in reality increasing numbers had both the freedom and the resources to enable them to realise their dreams in a way that was impossible when they were rearing children and/or in work. Laslett helped to popularise the term ‘The Third Age’ as a period when all these great possibilities could be explored, and as a time distinguishable for the first time in human history between the years as an adult in paid and unpaid work and the final period of decline and death. Laslett's thesis was based upon a belief in the broad horizons now open to most people in later life, horizons which for many were clearly not going to be restricted to narrowly defined communities of place. Perhaps the best example of this was how the Third Age debate was made ‘concrete’ through the rapid growth of the University of the Third Age across Europe after being established in France in 1973 (Midwinter Reference Midwinter1984).

This promotion of a positive Third Age was not without its critics, especially from those arguing for a political economy of old age. Both sides agreed on the importance of the emergence of retirement funded through state, occupational and private pensions. However, political economists of the period such as Estes (Estes, Biggs and Phillipson Reference Estes, Biggs and Phillipson2003), Phillipson (Reference Phillipson1982) and Walker (Reference Walker1981) emphasised how retirement was more about removal from the labour market to control unemployment rather than empowerment. In developed economies, those dependent on state pensions tended to remain the biggest group in poverty (Walker Reference Walker2005).

This whole debate was given a massive boost through the co-authored contributions of Gilleard and Higgs, first through Cultures of Ageing: Self, Citizen and the Body (2000) and then through Contexts of Ageing: Class, Cohort and Community (2005). The front cover of the first book showed a group of older women playing bowls at a seaside location and the second a sun-bathing older woman who is probably on a cruise ship and has a deep tan and clear indications of wealth. Both pictures express the central thesis of these two authors that the dominance of political economy perspectives in European and North American gerontology needed to be replaced by a focus on identity since:

Within consumer society the construction of identity is made up of a large number of choices. In the past, retirement has been an enforced choice connected to a decline of productivity or the need to remove older cohorts from the workforce. The circumstances in which retirement occurs now are more fluid and much more connected to lifestyle or, for some, redundancy. (Gilleard and Higgs Reference Gilleard and Higgs2000: 23)

As such, their work builds on the contributions of sociologists such as Giddens (Reference Giddens1991) and Bauman (Reference Bauman2001) in their attempts to understand the impact of marketisation, individualisation and globalisation upon everyday lives. Both Giddens (Reference Giddens1991) and Bauman (Reference Bauman2001) stress how the old mutual solidarities of place are being replaced by fragmentation and disengagement as a result of these macro-economic and social trends. This leads Bauman (Reference Bauman2001) to emphasise the fleeting and ‘fluid’ nature of many of the social relationships formed in the 21st century. This view has to be tempered by the research of Spencer and Pahl (Reference Spencer and Pahl2006) who evidence the often hidden solidarities of friendship which are no longer tied to ‘place’ but rather maintained through phone calls, texts, and the internet.

Gilleard and Higgs are not denying the continuance of inequality and poverty in later life but rather they are emphasising that ‘post-work lives have become richer and more complex’ (2000: 193) for many as a result of successive generations gaining increased access to ‘financial, cultural and social capital’ (2000: 193). In their second book, Gilleard and Higgs (Reference Gilleard and Higgs2005) focus down on the implications of these trends for community in later life. They argue that family has shown an ability to adapt so as to remain central to the lives of most older people (Phillipson et al. Reference Phillipson, Bernard, Phillips and Ogg2001) but the same is not true of community as understood as ‘the unalterable physicality of place’ (Gilleard and Higgs Reference Gilleard and Higgs2005: 126). In other words where older people live in terms of their street, village, parish and neighbourhood is playing a less critical role in the social construction of old age compared to other factors such as self-identity defined through a consumer-led lifestyle. They argue that this has opened up space for new types of community including those built around identity, interests and lifestyle.

However, they are sceptical about whether this will lead to a community of identity built around biological age because of the enormous variations in lifestyle. They are also angry at the moral distain often shown by gerontologists to those affluent older people who embrace fully the more hedonistic pursuits now available in later life such as gambling (Zaranek and Lichenberg Reference Zaranek and Lichtenberg2008) and drinking (Dar Reference Dar2006):

Dementia is not made more comfortable, nor emphysema more admirable, by the retired foregoing the gym, kicking off the trainers, deserting the cruise ships, or abstaining from playing the ‘slots’ in Las Vegas. (Dar Reference Dar2006: 162)

Although sharing much of the analysis of Gilleard and Higgs (Reference Gilleard and Higgs2000, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2005), Phillipson (Reference Phillipson2007) wishes to retain the stress of political economists on inequality in later life through emphasising what he calls the ‘excluded’ as well as the ‘elected’ in terms of experiences of place and community in old age. Globalisation does create ‘winners’ (i.e. Phillipson's ‘elected’) who in later life are able to adopt the privileged lifestyles outlined by Gilleard and Higgs and such people are able to choose the communities in which they live. Others, however, are marginalised by globalisation trends and may end up feeling excluded or trapped in their residential settings. Such people will have classically aged in place but the nature of this place will have changed dramatically for the worse from their point of view. The classic neighbourhood of this type in the UK would be in a large city with high rates of unemployment and poverty combined with poor housing conditions and the likely in-migration of ‘newcomers’ from Asia and Eastern Europe.

The enthusiasm of governments for social participation and civic engagement

As already indicated, Gilleard and Higgs (Reference Gilleard and Higgs2000, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2005) stress the reservations often expressed about what is seen as the selfish lifestyles of better-off older people in the 21st century. Increasingly, commentators are arguing that governments need to appreciate the gains to be achieved for the individual and society by shaping such lifestyle choices in later life to embrace high levels of both social participation and civic engagement (Deeming Reference Deeming2009; Gottlieb and Gillespie Reference Gottlieb and Gillespie2008; Kaskie et al. Reference Kaskie, Imhof, Cavanaugh and Culp2008).

Social participation is now at the heart of the public health agendas of nearly all governments facing a major ageing of their populations and the consequent cost implications for health and social services (Menec et al. Reference Menec, Means, Keating, Parkhurst and Eales2011). The following two examples illustrate the growing evidence base that social participation can improve both mental and physical health and hence has the potential to offset some of the costs of ageing populations. The first of these relates to visual art-making as a leisure activity for older women. Reynolds (Reference Reynolds2010) studied 32 such women aged between 60 and 86 years old, nearly all of whom had taken up art after retirement. Findings from this ‘community of interest’ indicated very positive impacts on subjective wellbeing, partly from the self-expression involved through such creativity but also through the way in which it built up valued connections outside the home and immediate family. The second example relates to research on leisure club participation by middle-aged and older women and this found that such participation increased social capital ‘including bonding and bridging opportunities, social support, sisterhood, and civic engagement’ (Son, Yarnal and Kerstetter Reference Son, Yarnal and Kerstetter2010: 67).

The important contribution of such cultural and physical activities to government was underlined by Building a Society for All Ages (HM Government 2009), which was produced by the outgoing Labour Government in the UK. This may have included a chapter called ‘Having the Later Life You Want’ (2009: 17–23) but it was a chapter with a clear health benefit message for older people. This message was about the benefits of ‘staying active’ and hence the announcement of ‘a new Active at 60 programme’ (2009: 21). This programme would build on free access to national museums and galleries as well as giving free access to swimming by:

commissioning 46 national governing bodies of sport to help create a world leading community sport system including plans to encourage the over 50 s to participate in sport. Physical activity currently decreases with age and at the moment the fitness industry is not taking full advantage of the market opportunities demographic change represents. (2009: 23)

This approach was maintained by the Coalition Government through its public health policy (HM Government 2010). The overall message of ‘healthy lives, healthy people’ included a commitment to ‘ageing well’ in which ‘local government and central government will work in partnership with businesses, voluntary groups and older people in creating opportunities to become active, remain socially connected and play an active part in communities' (2010: 50). Such developments illustrates the desire of the state to encourage, or perhaps even manipulate, older people into lifestyles (and hence often communities of interest) which will encourage both physical and mental health and hence reduce the financial costs to the state of poor health in later life.

Older people are being ‘sold’ the virtues of active ageing, which at its simplest can be defined as maintaining fitness, remaining active and staying involved (Deeming Reference Deeming2009). Active ageing has been heavily promoted to governments by the WHO as an effective route to maximising the health of older people (WHO 2001a, 2001b, 2002). However, the stubborn fact remains that there is enormous socio-spatial diversity in active ageing by older people, with those living in the more prosperous residential neighbourhoods participating in a far more diverse and rich range of pursuits than those from poorer neighbourhoods (Scherger, Nazroo and Higgs Reference Scherger, Nazroo and Higgs2011; Van der Meer Reference Van der Meer2008). Van der Meer (Reference Van der Meer2008), for example, studied the socio-spatial diversity in the leisure activities of older people in the Netherlands. He found that ‘education, income and the availability of a car have a positive relationship with participation in activities such as culture, going out and sport (2008: 11). Conversely, he found that older people in deprived neighbourhoods were most likely to exhibit ‘a meagre activity pattern’ (2008: 11).

One particular form of active ageing is especially popular with governments and that is civic engagement. Building a Society for All Ages (HM Government 2009) outlined a £5.5 million Generations Together Programme in England by which younger people could gain through learning from older people. It also promoted a more general emphasis upon volunteering in later life, which required the identification of volunteering opportunities ‘for example through trade unions, pension providers and company pension newsletters’ (2009: 50). Subsequently, the Coalition Government promoted the idea of ‘the Big Society’ (Norman Reference Norman2010) which placed capable communities and active citizens at the heart of policies for adult social care (Department of Health 2010).

This emphasis on civic engagement has its roots in the highly contested concept of social capital (Fine Reference Fine2010) as initially developed by Putnam (Reference Putnam1995: 667) who referred to ‘the features of social life – networks, norms and trust – that enable participants to act together more effectively to pursue shared objectives’. Evans (Reference Evans2009) described how Putnam had made a distinction between bonding social capital, which relates to closed networks of strong ties among family members, close friends and neighbours, and bridging social capital, which takes the form of overlapping networks of weaker ties. The argument is that social capital acts as a community resource and as such it is inviting people to engage in activities around their (communities of) interest(s) in order to improve civic life in their communities of place.

From a social capital perspective as presented by Putnam, civic engagement is at its simplest about ‘being involved with community and political affairs’ (Kaskie et al. Reference Kaskie, Imhof, Cavanaugh and Culp2008: 369). Older people are seen as ideal volunteers for a number of reasons. They have the time available and hence tend to show a long-term stable commitment to volunteering which increases their own social and cultural capital as well as that of the communities in which they live (Choi and Chou Reference Choi and Chou2010). More specifically, it is assumed that older volunteers ‘may enjoy good health and longevity because being useful to others instils a sense of being needed and valued’ (Gottlieb and Gillespie Reference Gottlieb and Gillespie2008: 399).

At first glance, all of this presents a virtuous circle of strong communities being supported by older volunteers who are in turn improving their own health. However, there are a number of problems with this rather simplistic analysis. First, the evidence base in terms of understanding the relationship of volunteering (and participation in other leisure activities) and good health in later life is far from adequate to draw definitive conclusions. Thus, Litwin and Schiovitz-Ezra (Reference Litwin and Schiovitz-Ezra2006) argue that it is the social ties that come with such activity rather than the activity per se which really matters in terms of supporting wellbeing in later life. In a similar way, affluent areas may have more resources than low-income neighbourhoods with which to support civic engagement. Deeming (Reference Deeming2009) has shown through his research in East London how such engagement in deprived areas is more likely to occur successfully with core funded services to support community participation and active ageing. In other words, civic engagement could become a new source of inequality between communities of place unless such investments are made.

Third, there is growing literature pointing to the naivety of the social capital and civic engagement literatures in terms of their failure to engage with power and conflicting interests within communities (Fine Reference Fine2010). Thus, for example, in a UK context, Moseley and Pahl (Reference Moseley and Pahl2007) have emphasised civic factionalism and in-fighting, while Curry (Reference Curry2010) explored the scope for a breakdown in trust in the context of the complexity of rural decision making at the local level. Both of these are UK examples, but Scott, Russell and Redmond (Reference Scott, Russell and Redmond2007) have illustrated how resident associations were undermined by property developers in the rural–urban fringe in Dublin in Ireland, while Wilshusen (Reference Wilshusen2009) studied the power of business elites to work against the interests of traditional communities in the context of community forestry in Mexico. This suggests that older people can be ‘losers’ as well as ‘winners’ from civic engagement. In some instances, older people may be divided amongst themselves on desired outcomes while in others their collective interests as older people may lose out to other more powerful voices.

Factionalism between different groups of older people does not have to take a dramatic form but can rather be manifested as a sense of distance and difference between older people with different biographies. The authors studied a Retirement Village which unusually combined a socially rented sheltered housing scheme with apartments owned through a variety of lease purchase arrangements (Evans and Means Reference Evans and Means2007). The promotional brochure for the village spoke of ‘a lively balanced community’ appealing to older people with a background in both owner occupation and renting, with the developers having high expectations of interaction across the diverse community. The researchers found that despite these aspirations there was relatively little interaction between the residents of the lease purchase apartments and those who were renting within the sheltered housing complex. Most of the communal facilities of the village were located in the extra-care housing complex and these tended to be much more intensively used by the extra-care residents than by those who had lease purchased.

Against this, many of the residents of the lease purchase apartments sought their main social interaction through the village croquet club. As one lease purchaser explained:

The croquet club got everybody to know one another. We were all strangers but we soon knew one another's Christian names so we were soon chatting together. And we got into a little group all through the summer. By the time the end of summer came and that stopped we were sort of having coffee with one another … and that's gone on from that now and it's a good social unit really. (Quoted in Evans and Means Reference Evans and Means2007: 29)

The croquet club was an important community of interest for a significant proportion of the lease purchasers. Instead of being a single community, this Retirement Village was characterised by a considerable social distance between the lease purchasers and the extra-care housing residents. One of the latter went so far as to refer to ‘that lot up there’ and ‘us down here’ (quoted in Evans and Means Reference Evans and Means2007: 42) while a lease purchaser said it was like having ‘a council estate next to a private estate’ (2007: 44). This last quote does, of course, raise the issue that this Retirement Village might after all be a typical English village in terms of social differentiation between ‘the haves’ and ‘have nots’. However, for the purpose of this article, the key point is how residents constructed their new lives in this Retirement Village around a number of communities of interest.

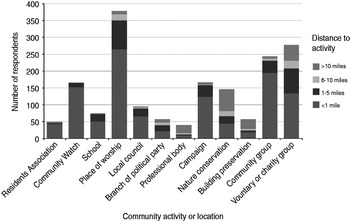

Finally, ‘the Big Society’ view of civic engagement not only assumes community cohesion but also that social and civic activities are all embedded within the community. However, it is clear that Phillipson's (Reference Phillipson2007) ‘elected’ often pursue such activities over a wider area than their immediate neighbourhood, as confirmed by the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) (Scherger, Nazroo and Higgs Reference Scherger, Nazroo and Higgs2011). Levels of participation in activities were shown to be linked to socio-economic circumstances, with those of higher educational and occupational background maintaining or increasing their involvement over time compared with other groups. The complexity of participation is further underlined by a recent survey of older people in six rural communities, three in England and three in Wales (Shergold and Parkhurst forthcoming). Findings confirmed that some pursue activities at a considerable distance from their home but also that the majority engage with social activities and civic participation very close to where they live. As Figure 1 shows, respondents took part in a wide range of community activities and travelled a range of distances to do so. While 63 per cent of all reported activities take place less than a mile from the home of participants, 20 per cent are between one and five miles away and 17 per cent are at a distance of six miles or more. Overall, the data supports the assertion of Dobbs and Strain (Reference Dobbs, Strain and Keating2008) based on a Canadian study, that while mobility is key to enabling older people to remain connected to rural communities, it is important to recognise the heterogeneous nature of older people and the diversity of the communities to which they belong.

Figure 1. Distance travelled to take part in civic activities.Note: Respondents may have used single trips to take part in multiple activities.Source: Taken from Shergold and Parkhurst (forthcoming).

The next section explores issues relating to the capacity of new technologies to further support the growing importance of communities of interest to older people.

The internet and virtual communities

Changes driven by the development of technology are starting to have an impact on older people's quality of life and experiences of community and neighbourhood. One such change is the phenomenal growth in the provision of consumer services via the internet, which has been a factor in the closure of many local retail and service outlets. For example, in the UK 2,500 post offices closed during 2007–08 and 4,000 bank branches ceased trading between 1995 and 2003. With similar trends are evident for other services such as local shops, libraries and local health facilities, there are likely to be reduced opportunities for social interaction for older people in particular. This can have a significant impact on independence, but it is possible that it is also affecting the extent to which community attachment is maintained.

Another significant technological development in recent years is a phenomenal increase in the number of communities of interest that operate over the internet, often know as ‘virtual’ or ‘online’ communities such as Facebook, MySpace and Friends Reunited. The popularity of these sites is staggering. For example, Facebook had more than 750 million active users in 2011, half of whom log in on any given day (Facebook 2011). Such sites host high levels of social interaction (Scott and Johnson Reference Scott and Johnson2005) and share a range of characteristics with place-based communities, including the development of common norms of trust and reciprocity and the existence of inbuilt systems of governance and behavioural control. Online communities are often viewed as a challenge to traditional concepts of community, the argument being that they replace face-to-face forms of social interaction (Rheingold Reference Rheingold and Ludow1993). However, the evidence suggests that online communities can actually lead to increased social interaction in non-virtual spheres. For example, Wellman and Gulia (Reference Wellman, Gulia, Smith and Kollock1999) found that much online contact is between people who live close to each other and functions as a way of getting to know each other. It can be argued that online communities are just as real as place-based ones, simply because their members perceive them to be real (Evans Reference Evans2009; Harasim Reference Harasim1993). This line of reasoning suggests that the internet is a virtual place that people visit as a venue for social interaction, just as they might go to the pub or a shopping centre to meet their friends. Electronic villages are one manifestation of this phenomenon, with their aim to extend and complement existing physical communities by bringing citizens together around shared interests and enthusiasms. A good example of this approach is Blacksbury Electronic Village in Virginia, USA (www.bev.net), which invites web users to register as e-villagers and includes a section for ‘Seniors’. We argue therefore that new technologies support the development of communities of interest in both geographical and virtual spheres.

Bearing in mind the opportunities that the internet provides in terms of accessing services and enjoying social interaction, it is important to note that levels of computer use in general and internet access in particular are relatively low for the current cohorts of those who might be seen as ‘older people’. For example, in the UK 60 per cent of those aged over 65 have never used the internet, compared with just 1 per cent of those aged 16–24 (Office for National Statistics 2011), while in the United States of America usage figures are 90 per cent for those aged 18–29 and 46 per cent for the over 65 age group (Pew Research Center 2010). There is evidence to suggest that many older people who are currently not using the internet would do so with the appropriate support (Ofcom 2006). This desire to get ‘connected’ is reflected in the emergence of social networking sites targeted specifically at older users. These include sagazone.co.uk, which launched in 2007 with the mission of providing ‘an online community where you create a whole new network of friends’. It seems likely that increasing numbers of older people will enjoy the benefits of social interaction through online communities, particularly as those baby boomers who have gained computer experience in the workplace join the ranks of the over 65 s.

Given the potential of the internet to promote social interaction and community belonging, it is important that older people are supported to make use of such technologies, through for example increased levels of broadband access, advice and support, and age-friendly design. If this support is not provided there is a danger that significant numbers of older people will become excluded and isolated from important facets of community life.

Communities of place and communities of interest in later life: concluding comments

The central argument of this article is that communities of interest play a growing role in the lives of many older people, but that it is not helpful to pose them as the present-day alternative to communities of place. The task is rather to unravel the complex ways in which the two interact and overlap and this article has sought to draw out some of the ways in which this occurs.

First, at a very practical level, older people pursue their interests in a whole variety of ways, some of which help to bind them to their local neighbourhood and some of which draw them away from a central focus on the locality in which they live. Church membership is a good example of this. A strong engagement in a church community can mean attending the local church and engaging in a series of civic engagement activities in the local neighbourhood as a result. However, the church may be a more ‘specialist’ one such as Jehovah's Witnesses in which considerable distances have to be travelled in order to participate. Such a church may expect a very strong engagement as a church community but the consequent activities are much less likely to be grounded in a specific local neighbourhood.

Second, linked to this there is a real tension with the growing emphasis of governments upon the obligations of older people to volunteer and hence be civically engaged. This tends to assume that all older people will want to engage ‘with their own community’, which is understood in terms of traditional concepts of place. Similarly, Menec et al. (Reference Menec, Means, Keating, Parkhurst and Eales2011) highlight the tension with underlying agendas related to the devolution of government responsibilities to communities/individuals. These observations support suggestions that the simplicity of ‘the Big Society’ sits uncomfortably with the complex lives of older people in the consumer culture outlined by Gilleard and Higgs (Reference Gilleard and Higgs2000, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2005).

Third, researchers on ‘community’ need to engage fully with the massive impact of the internet, especially in terms of the future lives of older people. This article has reviewed the present evidence on usage but we also need to allow for how the baby-boomer generation will grasp these possibilities as they retire, together with the new possibilities that continue to emerge as a result of technological advances. At one level, this opens up the possibility of the maintenance of communities of interest that span continents but at another level it is already the mechanism by which a myriad of neighbourhood groups stay in touch and communicate on a day-to-day level. The internet also opens up the prospect of retaining engagement with interests and enthusiasms despite the onset of illness and frailty.

Finally, running throughout this discussion are the inequalities of later life that help to shape opportunities for lifestyle choices, including social activities and civic engagement. Scherger, Nazroo and Higgs (Reference Scherger, Nazroo and Higgs2011) underline how ‘the better off’ are far more likely to have a depth and spread of activities than those on lower incomes. However, older people in more advantageous situations are likely to use their social capital both within their neighbourhood as well as beyond it. This article has explored some of the reasons why it is not helpful to pose communities of interest in later life as the present-day alternative to communities of place in the past. It is not a case of coming down in favour of the prime importance of ‘interests’ or ‘place’ but rather the need to reconceptualise how they intersect in contemporary society.

Acknowledgements

This paper is an output from a research project entitled ‘Grey and Pleasant Land? An Interdisciplinary Exploration of Older People's Connectivity in Rural Civic Society’.

The project is funded by the ESRC under the New Dynamics of Ageing Programme (Grant No. RES-353-25-0011). The authors would like to thank Professor Nigel Curry for his comments on a draft version of this paper.