In fall 1987, Pennsylvania State Legislator Thomas Fee traveled to Washington, DC, for a meeting between Pennsylvania’s General Assembly and congressional delegates. He noted that the meeting between the state and federal representatives sparked a lively discussion on the issues vital to the country and fostered a deep sense of national pride. However, after the speeches, panels, and discussions ended, he could not contain his disappointment with the dinner served. After eating, he flipped over his plate to see who manufactured his dinnerware, a habit common among many men and women who grew up in a town with a pottery. To his great disappointment, he found the plate marked “made in Japan.” Being from New Castle, Pennsylvania, he knew that Shenango China, manufactured in his hometown, and other American potteries had suffered for years due to the constant onslaught of foreign china manufacturers, whose workers made low wages as compared to their American counterparts. He chastised the House Administration Committee for not supporting struggling domestic manufacturing in favor of the cheaper option. “If officials of the government of the United States of America cannot be relied upon to support American industry,” Fee questioned, “what hope remains for establishments like Western Pennsylvania’s Shenango Pottery? Unprotected from foreign competition, their future is bleak.”Footnote 1

For American commercial potteries, foreign imports represented a persistent problem that haunted the industry from its earliest days. While companies tolerated English, French, and German products due to their closeness in quality to U.S. products and wages paid to U.S. workers, the emergence of Japan as a major competitor, beginning in the 1920s, proved a challenge they struggled to overcome. Through the following decades, American manufacturers tried a number of strategies to either dissuade consumers from Japanese pottery or to prevent the sale of the product at low prices in the United States. Through all of their trials, however, pottery heads neither formulated the unified front needed to tackle this newcomer nor agreed on the strategies needed to improve their own products in comparison. The management of individual companies as well as trade associations presented only a lukewarm defense against Japanese home dinnerware. When a U.S. plant owner then suggested the manufacture of vitreous hotel china in Japan, the American industry went to war with itself. The ultimate result was that each year Japan introduced more ceramic products into the United States, and each year American potters struggled more until only a small handful remained. Of these, Lenox China and Pickard China manufactured fine porcelain for the high end of the market (products not heavily imported from Japan), while Homer Laughlin balanced both foodservice and home lines while retaining their family management, a feat not accomplished by other plants that fell to outside corporate ownership.

The failure of these potters in the face of imports illustrates the woes of the current handicraft industries in the United States, and raises the following questions: Is their decline an inevitable part of a globalized economy? Do management strategies play a part in their company’s failure (or success)? Historiographical debates on deindustrialization often focus on either general plant closures or on the aftereffects on workers and their community from singular plant closings. Rarely do managers look at the actions of individuals in trying to prevent the failure of an entire industry.Footnote 2 Whether for good or for ill, the actions that management takes in the face of competition directly affect their company’s ability to survive. In looking at the American commercial pottery industry, the heads of these companies placed too much faith in an uninterested government tariff policy and in the good faith of consumers to choose American-made over lower cost. They also spent too much time attacking one another’s strategies instead of coming up with ways to strengthen their industry as a whole. As a result, they did not prepare for the intrusion of Japanese-made wares into the marketplace, which accelerated their own demise.

The State of the American Pottery Industry through World War I

American pottery began with English producers who came to the United States in the early nineteenth century. Staffordshire, the center of English pottery manufacturing, experienced a slowdown, prompting the migration of skilled workers to the United States. Here, they found ready capital, established markets, and transportation systems. By 1850 pottery manufacturing in the United States moved beyond goods produced for local markets and into a commercial enterprise. The first center of this market grew up around the area of Trenton, New Jersey. Trenton provided a source of cheap land, raw materials, and easy access to major markets in New York and Philadelphia. Over the next thirty years, Trenton remained the major pottery hub in the United States, but by the 1870s East Liverpool, Ohio, and its surrounds emerged as a major challenger. Like Trenton, East Liverpool enjoyed market access, this time through the Ohio River and local railroads. While both made use of local clays at first, the discovery of kaolin clay in the Carolinas allowed for the production of the country’s first white ware, a product in much higher demand than yellow or tan (Rockingham) ware.Footnote 3

By the turn of the twentieth century, Trenton’s potteries struggled to keep up with those in Ohio. Most of the early Trenton potters had come directly from Staffordshire, and thus had copied the journeyman labor system with its high wages and long apprenticeships. Unionization (first done through small, local organizations and later affiliated with the Knights of Labor) also damaged relations between workers and management, resulting in major strikes in 1864, 1869, and 1877. Meanwhile, East Liverpool’s industry developed with unskilled laborers and mass production techniques. In time, Trenton’s antiquated system could not keep up with the less expensive product coming out of Ohio. By the 1890s, many Trenton potters either shifted their attention to sanitary ware (that is, plumbing fixtures) or faced shutdowns. East Liverpool potteries, which numbered nearly 100 by 1900, led the nation in earthenware, a semi-vitreous pottery product cheap to produce but absorbent of liquids and flavors.Footnote 4 Still unable to produce fine porcelain, potteries in Ohio and those beginning to spring up in Pennsylvania and New York did develop yet another product. They succeeded in firing a fully vitrified ware (completely resistant to absorbency) but with thicker walls than traditional dinnerware. While unsightly for home use, the thickness made it less prone to breakage and ideal for the emerging hospitality and restaurant markets. The ware got the nickname hotelware, and it provided American producers with a product uniquely their own.Footnote 5

As the American commercial pottery industry matured in the late nineteenth century, three major players emerged that would in time lead the market in sales and pieces produced. In 1873 Homer Laughlin received funds to open a pottery along the Ohio River in East Liverpool. After a rough beginning, Laughlin produced white ware of high enough quality to win recognition at the 1876 Centennial Exposition, in Philadelphia. With capital from the Aaron family of Pittsburgh and leadership from William Wells, the plant’s general manager and owner following Mr. Laughlin’s 1894 retirement, the Homer Laughlin China Company grew into the leader of the Liverpool potteries. It rapidly expanded to three plants in Ohio before crossing the river and opening huge complexes in Newell, West Virginia, which utilized mass production and modern technologies such as the tunnel kiln. In 1936 the company introduced its signature product, Fiesta®, which took advantage of the then current art deco craze and featured concentric circles and bold, bright colors that fit the look of modern homes. By the end of the 1940s, Homer Laughlin produced millions of pieces of Fiesta and other semi-vitreous dinnerware each year, accounting for one-third of all American-manufactured dinnerware in the United States.Footnote 6

Other American potteries gained prominence through a combination of earthenware and hotelware production. Both Onondaga Pottery, in Syracuse, New York, and Shenango China, in New Castle, Pennsylvania, made their fortunes through attracting different markets. Onondaga got its start in 1871 by manufacturing white and cream-colored ware. The plant hit its stride in 1891 when James Pass, president of the company, introduced Syracuse China, a vitrified dinnerware. He continued this success with the 1896 introduction of roll-edge hotelware, and in 1908 he successfully transferred the first multicolor decalcomania onto his product.Footnote 7 After several unsuccessful starts, the Shenango China plant recovered under the leadership of James M. Smith, who took over the plant in 1908 and quickly grew it into one of the most successful potteries outside of East Liverpool. Shenango initially focused solely on the production of hotelware, adopting mass production and becoming one of the first plants to install a tunnel kiln, which cut down firing time from two weeks to five days. In the 1930s, Smith entered Shenango into the fine porcelain business, securing a contract to produce France’s Theodore Haviland China in the United States. Ten years later, Shenango developed its own vitrified china dinnerware: Castleton China.Footnote 8

By the middle of the twentieth century, Homer Laughlin produced a significant amount of the semi-vitreous earthenware in the country, while Shenango and Onondaga together accounted for more than half of the country’s hotelware and a significant amount of its vitrified dinnerware. It took a combination of time, skill, and outside luck to achieve this feat. Because the American pottery industry developed as a result of men and technology from England, it initially struggled to keep up with its Atlantic counterpart. Since American china consumers tended to equate imports with quality well into the early twentieth century, the first competition to the potters of the United States remained European. The display put on by the United States Potters Association (USPA) during the Columbian Exposition in 1893, in Chicago, greatly increased consumers’ knowledge of American pottery, yet it did not translate to an increase in sales. Neither did the 1894 tariff, despite that it greatly increased the duties on foreign-made china. USPA Secretary Alfred Day complained that the tariff increase should curtail British sales to the point that the home-grown producers could take over a significant share of the market, yet they could still not convince buyers that American pottery could match European pottery in quality.Footnote 9

Indeed, as Regina Blaszczyk notes, foreign china held a tremendous amount of sway on the American market at the end of the nineteenth century. The china import industry consisted of a network of middleman buyers (called “jobbers” by the trade) who traveled through the pottery districts of England, France, and elsewhere. When they saw a product they felt would sell in the United States, they placed an order and paid for it to be shipped across the Atlantic. Upon arrival, they either marketed the ware themselves from their importation offices or sold it to specialty and department stores.Footnote 10 The china and glass district in New York City stretched across several city blocks in the vicinity of Broadway and Chambers Street, where dozens of jobbers displayed the finest European porcelain for their out-of-town buyers. Importers undertook aggressive marketing campaigns to promote foreign china as better quality, more luxurious, and a way for American homes to emulate the tradition of European elites.

American consumers remained reluctant to wholeheartedly embrace domestic earthenware and dinnerware until two world wars gave them little choice. Following the destruction of European plants in France and Germany during World War I, American manufacturers saw a significant increase in sales. World War II again greatly increased American pottery production; many plants worked three shifts not only fulfilling government contracts but also producing for the domestic market in the absence of the potteries of Britain, France, Germany, and Japan, all of which shut down entirely or curtailed their exports to the United States. A study by the Vitrified China Association, a trade association for hotelware manufacturers, found that at the war’s end, America’s pottery production increased tenfold to make up for the lack of an import market, and that by 1947 earthenware and vitreous plants combined employed more than twenty-seven thousand workers, an increase of more than ten thousand over 1939. By 1948 American potters manufactured 2.4 million dozen pieces each year, with sales totaling $10.7 million ($8.1 million in hotelware and $2.6 million in household dinnerware, both earthenware and vitreous).Footnote 11

Homer Laughlin China, Shenango China, and Onondaga Pottery all enjoyed their own personal successes in the immediate postwar period. Don Schreckengost joined Homer Laughlin as its art director in 1945, replacing the deceased Frederick Rhead, creator of Fiesta. Like his predecessor, Schreckengost valued a truly American style of design (emphasizing bright colors and bold patterns over traditional floral pastel motifs, and shapes inspired by modern art rather than a traditional coupe) and worked to move his shapes and styles as far from the tradition of Europe as possible. Noting the continued success of Homer Laughlin’s Fiesta, Schreckengost developed several of his own colored dinnerware lines, including Rhythm, Epicure, and Jubilee, a shape designed in commemoration of the company’s seventy-fifth anniversary in 1948.Footnote 12 Fiesta itself underwent changes in its color scheme, reflecting both necessity and adaptation to changing fashion and consumer tastes. During the war, the government claimed all available uranium oxide in anticipation of continued conflict. This compound formed the main component in the red Fiesta glaze, so red “went to war” until the late 1950s. To keep up with current color trends, the original light green, cobalt blue, and ivory ceased production in favor of forest green, chartreuse, pearl gray, and rose pink.

At Shenango, the manufacture of both dinnerware and hotelware continued to the tune of ten thousand dozen pieces per day in four thousand shapes and with seven thousand decorations. By 1949, between its Castleton China line and its production contract with Theodore Haviland, the company produced one-third of the entire nation’s hotelware and over half of the fine china. The company also added a refractory plant in 1946 to produce its own kiln components as well as to contract out production for other potteries.Footnote 13 Onondaga Pottery celebrated its seventy-fifth anniversary in 1946. The year prior, Onondaga introduced its revolutionary Airlite China, the first successful thin vitrified china made with a high concentration of alumina, which kept hotelware durability but at a fraction of the weight. The name came from the adoption of Airlite, from the first china used on commercial passenger airlines. It also kept up production of the dinnerware line Syracuse China in a variety of shapes and designs.Footnote 14

For roughly the first three years following the end of the World War II, American potteries enjoyed success not only from the lack of competition but also from the booming postwar American economy. Historian Lizabeth Cohen argues the ideal of citizen consumers first embraced by the New Deal grew into a full-fledged “consumers’ republic” during the Cold War, when the defense of capitalism began in the purchases made by American households. A coalition of government, business, and labor urged consumption as a type of civic responsibility and a way to restore employment while furthering the standard of living.Footnote 15 As hoped, the American postwar economy enjoyed steady growth and, with the exception of a few brief downturns, managed to erase the memories of the Great Depression and the scarcity caused by war. From 1946 to the early 1970s, the United States enjoyed a doubled family income, exponential growth of production, and low levels of unemployment in major industries.

Japan Enters the Dinnerware Market

Following World War I, American pottery manufacturers finally felt they possessed the market share to coexist successfully with products from Europe. At the same time, the war brought a new competitor to the American market, one that would prove to be a headache for the rest of the American pottery industry’s existence. Buried deep in a 1905 report on the loss of English market share, the USPA noted that china from Japan started entering the United States in rapidly increasing quantities.Footnote 16 This country posed a special threat to American manufacturers because their wages fell well below the collectively bargained rate of pay for workers in the United States, so that even the tariff could not make up for the large difference in price. While American potteries produced more products with each passing year, the high cost of skilled labor (and labor unions) led to a low profit margin on the final sale. If Japanese workers earning a fraction of the wages could undercut U.S. prices, the entire American market would suffer.

World War I devastated the potteries of Europe, opening the door not only for the increased output of American manufacturers but also to imports from Japan. The Japanese economy struggled following their 1905 war with Russia, but WWI helped turn the tide; by 1915 exports totaled ¥130 million over the previous year and more than the total amount of export sales combined since the beginning of the Meiji Restoration. With German factories shut down or destroyed, Japan filled the void for cheap earthenware pottery, getting so many orders that not all could be filled in a timely manner.Footnote 17 Japan specialized in cheap, white, undecorated ware, but in 1916 the body of the product looked and felt inferior to American earthenware and suffered from problems such as crazing (a web-like pattern of cracks in the glaze).

The editor of the trade journal Crockery and Glass Journal reported on Japan, noting that while the product lacked a level of craftsmanship, their potteries had improved steadily over the previous few years and would continue to do so after the end of the war. This concern preoccupied the USPA, who sent William Burgess to inspect the Japanese potteries in 1920 and to report back at the annual USPA convention. Burgess described an industry on the precipice of transitioning to modern manufacturing. Many of Japan’s factories developed around Nagoya, and like the early American industry, production depended on local clays. While many of the smaller plants relied on old-fashioned methods, others rapidly modernized with technology unavailable even in many American plants. Most telling, the workers in Japanese potteries earned, on average, the equivalent of US$0.60–0.85 per day, at a time when many American potters earned that per hour, and unionization in Japan was strictly forbidden.Footnote 18

These advantages meant that Japan could produce pottery for a fraction of the cost of American earthenware producers, many of whom operated small plants and were unwilling or unable to absorb the costs of new technologies, such as the tunnel kiln. By 1925 the USPA reported that sales plummeted that year despite much of the rest of the American economy booming. Sales of vitrified hotelware dropped 2.61 percent (a loss of $254,857 from the year prior) while earthenware dropped 6.26 percent, losing $2,418,229.Footnote 19 While the reasons given varied from poor tariff enforcement to a lack of adequate investment by pottery heads, chief responsibility pointed to the presence of cheaper foreign products with which earthenware potters could not compete. As the Great Depression gripped the nation, the situation further deteriorated, with USPA statistician John Dowsing reporting in 1933 that imports from Japan rose 69 percent from the previous year. That country now exported eleven times as much as Britain or Germany, a staggering 519,501 dozen pieces per month, and growing. Dowsing also accused the Japanese of misrepresenting the value of their goods to the U.S. Customs Office, which allowed them to pay a lower tariff rate. While the USPA applied for emergency relief from Japanese goods through the National Industrial Recovery Administration (NIRA), Dowsing doubted the government would do much to assist America’s potters, and indeed the NIRA rejected the petition based on Secretary of State Cordell Hull’s emphasis on free trade.Footnote 20

When Japan joined the Axis powers during World War II, American bombing campaigns targeted industrial sectors, including the pottery center at Nagoya (which also manufactured aircraft during the war), resulting in the destruction of many pottery plants and crippling those that remained. After the war ended, however, the U.S. government looked to secure democracy by promoting capitalism abroad, especially in the defeated nations of Germany and Japan, which could fall to communist sway without proper support. The United States also feared a “dollar gap” between the booming American economy and that of other nations that could not afford to purchase American-made goods. Closing the gap became a top priority of U.S. foreign policy out of fear that the lack of purchasing power would lure these nations to a communist economic structure; thus, the United States pumped large amounts of money into these foreign economies. Japan in particular remained critical, and following America’s occupation in 1947, policy turned toward rebuilding the Japanese economy on the U.S. model. Over the next eight years, the United States gave $2 billion in aid to Japan and sent advisors and technology to restore industrial production.Footnote 21

As part of rebuilding Japan’s economic infrastructure, the United States pledged to bolster that economy by purchasing large amounts of Japanese-made goods. By 1955 government orders alone topped $4 billion. American businesses welcomed the strengthening of the Japanese economy as large corporations called for freer trade in order to grow their own presence abroad. With the opening of the world market, policymakers encouraged Japan to resume exportation. Indeed, helped by improving technology and lax tariff policy, Japanese exports to the United States doubled from 1955 to 1960.Footnote 22 On the surface, encouraging Japan to flood the American market seems counterproductive. Economist William Borden explained this paradox as follows: “The United States and other capitalist industrial powers were both competitors and economic allies. Whereas some economic groups within each nation would lose from foreign competition, other groups, usually more powerful, would gain.”Footnote 23

The pottery industry clearly fell into the realm of groups set to lose from foreign competition after the end of U.S. occupation in 1947. After 1948 the gains made during the war and in the immediate postwar years quickly dissipated, plunging America’s potteries into a struggle for their very survival. Even during the war, Joseph Wells Sr., now president of Homer Laughlin following his father William’s retirement as well as the chair of the USPA Labor Committee, expressed concern over the return of foreign imports and stated that he hoped that Japan would never be allowed to recover its manufacturing plants, as “the members of our organization know from their business experiences with the Japs that they never could be trusted to do business in an honorable manner.”Footnote 24 However, this hope proved very short-lived. Over the protest of labor union leaders, including James Duffy of the National Brotherhood of Operative Potters (NBOP), the State Department sent delegates to Japan to determine which goods could be exported to the United States with little impact on American employment. Indeed, semi-vitreous pottery fell into the group of products Japan had permission to export in greater quantities, and by 1948 the amount of imported earthenware surpassed American-made goods for the first time since the war.Footnote 25 That December, Wells noted grimly, “For the first time in eight years, we have an unemployment situation in our industry […] Japan exported more than four times the quantity of china and earthenware [than] she did in September 1947.”Footnote 26

Why Was Japanese Dinnerware a Problem?

Imports of dinnerware presented a problem for several reasons, but mainly for the wages that sometimes were as low as one-tenth of those in the United States. Both the USPA and the NBOP complained of Japan’s cheap labor costs as far back as the 1930s, but after World War II they connected this issue to the costs of their own production. Wells noted that for every dollar made by Homer Laughlin in 1944 (when the plant experienced high levels of production), 65 cents went directly to the wages of factory laborers, office workers, and foremen. Another half of 1 cent went to executive salaries, and 2.5 cents to stockholders. The remaining 33 cents paid for insurance for the plant; equipment maintenance; workers’ Social Security and health benefits; taxes; and the purchase of raw materials. While sales at Homer Laughlin remained steady, in reality the plant veered close to losing money each year from the high cost of labor.Footnote 27 Wells continued to note that his figures reflected those of other dinnerware plants. Pottery, even in an age of mechanization, retained much of the handicraft tradition in its manufacture: certain parts of the manufacturing process could not be easily replicated by machine.

The struggle of manufacturers was compounded in the 1950s by a series of work stoppages, both “wildcat” walkouts and an official strike called by the union, now known as the International Brotherhood of Operative Potters (IBOP). Nine hundred employees walked out of the Homer Laughlin China Company in September 1952 for a period of two weeks, and they set up picket lines to prevent the rest of the plant’s twenty-five hundred employees from entering the building. Four years later, another illegal stoppage, this time at Homer Laughlin, at Edwin M. Knowles, and at Taylor, Smith, and Taylor idled forty-three hundred workers for ten days. In September 1959 the IBOP called its first general strike in thirty-seven years, idling seven thousand workers at a dozen plants for a period of twenty-eight days.Footnote 28 Not only did pottery heads pay more in concessions to end the stoppages but also they lost millions in business from unfilled or late orders.

Another problem for the potteries was that rather than try to cut their own costs, American pottery heads often took their case to Washington, DC, to complain about imports. In 1950 representatives of the Vitrified China Association, the USPA (by this time representing only earthenware manufacturers), and the IBOP testified before the House Committee on Education and Labor’s special hearings on the effect of imports on domestic employment. All argued that Japan benefited from American dollars and machinery, yet Japanese companies continued to underpay their workers and employed women and children to drive wages even lower. With imports taking 35 percent of the combined American earthenware and fine china home market, and Japan not even back up to full strength yet, the results would continue to cripple potteries in the United States. Sales by USPA members fell from $77.5 million in 1948 to $64 million (a 17 percent drop) in 1950; meanwhile, import sales rose to $20 million (an increase of 24 percent) in that same period. At Homer Laughlin, Wells noted that sales dropped by one-fourth in the first three months of 1950 alone, necessitating a dramatic increase in unemployment and a cut in hours for those still on the job. In all, more than five thousand pottery workers across all Ohio and West Virginia plants lost jobs or fell to part-time hours. He continued that the local pottery plants accounted for a large percentage of employment and income for many small communities. Additionally, pottery employment tended to be multigenerational, meaning that job loss affected every wage earner living under the same roof. Furthermore, America’s potteries could not try to sell their own product abroad as the higher cost from American labor, combined with predatory tariffs in other nations, made the ware too expensive to appeal to foreign markets. While a free market helped large multinational corporations, small industries like pottery suffered. Both Wells and Duffy pleaded with the committee to consider a quota on imported dinnerware to make up for the inadequate tariff. They pointed out that even though the State Department generally considered quotas a restriction of trade, they previously made exceptions for other industries, such as sugar and cotton. A quota of even 25 percent could save thousands of jobs for American pottery workers.Footnote 29

The House Committee rejected the passage of a dinnerware quota, so for America’s earthenware potters the situation continued to deteriorate. By 1951 the USPA proclaimed “a depression in the midst of a booming economy” as many plants operated at half-capacity or less. Wells noted that in 1950 sales for all American dinnerware manufacturers totaled only $150 million, and that Homer Laughlin sales came to $13 million for the year, a drop of $3 million that caused multiple layoffs totaling four hundred workers. Sales of imports from Japan jumped from $2.37 million (2 million dozen pieces sold) in 1947 to $4.18 million (4 million dozen pieces) in 1948, to $17.2 million (9.8 million dozen pieces) in 1957, and to more than $17.7 million (with 14 million dozen pieces sold) by 1961.Footnote 30 In 1958 Homer Laughlin lost money for the first time in its eighty-five-year existence and could not pay dividends for the first time since 1905. Employment at the plants in Newell, W. Virginia, dropped from a peak of 4,200 workers in 1948 to 1,450 in 1960, with many of those working less than thirty-one hours per week. Between 1954 and 1961, fifteen other major plants closed their doors forever, devastating local communities with approximately ten thousand jobs lost in plants that had operated since the previous century.Footnote 31

The low wages of Japanese pottery workers in comparison to American workers remained the most significant threat to the industry, but it was not the only one. Japanese pottery often reflected its cheapness in its poor quality, yet stores continued to sell it for a high profit margin. As far back as 1936, Frederick Rhead, the art director at Homer Laughlin, observed that much of the dinnerware coming from Japan “would not be accepted by any American dealer if it was shipped from any American factory.”Footnote 32 Even after the infusion of U.S. dollars and equipment following World War II, Japanese ware varied greatly in quality, with some pieces nearly indistinguishable from American products while others exhibited poor craftsmanship and manufacturing prone to breakage and crazing.

This unevenness not only reflected the poor quality of imported ware but also harmed the U.S. industry as a whole. For example, Japanese-made china injured American producers by often blatantly copying designs, shapes, and patterns. This practice, too, went back to the earliest arrival of Japanese wares on the market. A display of Japanese china at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago was meant to alert domestic dealers to Japan’s ability to use designs copied directly from American plants. By 1933 Rhead, who was also the chair of USPA’s Art and Design Committee, called the Japanese display at that year’s Chicago’s Century of Progress International Exhibition “notorious,” observing the number of booths displaying direct copies of “everything one would see in a large American department store.” Among the copies were bicycles, men’s and women’s clothing, hardware, drugs, foodstuffs, and, of course, pottery in a range of bodies and decorations in both china and earthenware. To combat the problem, the USPA first turned to the U.S. government, petitioning the Federal Trade Commission in 1936 to take action on Japanese copies of a leading American design.Footnote 33 The commission traveled to the Japanese factory and condemned the practice, but it did not stop the plagiarizing because Cold War harmony took precedence in the postwar period. American government officials either turned a blind eye to the copying or felt the practice did not cause enough damage to warrant further investigation and resources.

With little aid coming from their own government, members of the USPA then turned to the producers of the copies to halt the practice. Over the years, companies such as Homer Laughlin, Edwin M. Knowles, and Salem China reached out to the Japanese government for assistance. For its part, Japan complied and halted production on designs found to be copies, noting that the uniqueness of design played a vital role in the industry. A Japanese trade paper sent to the USPA included a story on that government’s efforts to crack down on piracy in design as a measure of both business practice and international harmony.Footnote 34 In 1958 the major manufacturers and exporters of that nation organized the Japan Pottery Design Center with a goal of keeping a record of all designs trademarked in the United States and thus prohibited from being copied. Within two years, the file grew to twelve thousand designs and even more waiting approval. The center also mediated disputes over copies, settling fifty-one cases over the previous two years.Footnote 35

Despite this effort, issues regarding design plagiarism continued, sometimes from Japanese companies looking to deliberately benefit from popular American patterns, but at other times from unscrupulous distributors in the United States who deliberately ordered designs they knew to be copies. In October 1959 an Onondaga Pottery executive discovered that the grocery chain Giant Foods began offering a premium china set whose pieces directly copied the Onondaga patterns “Blue Mist” and “Bridal Rose,” but sold under the similar name “Colleen Rose.” Further inspection found the china came from the Stanley Roberts Company, which imported it from a Japanese manufacturer. Onondaga filed a lawsuit against Stanley Roberts and Giant Foods for copyright infringement that December. A judge eventually awarded Onondaga $8,000 in damages from Stanley Roberts (though allowing the importer to sell off the remaining sets) as well as $1,000 in damages from Giant Foods.Footnote 36 Before that case even closed, more Onondaga copies surfaced, this time in the patterns “Meadow Breeze” and “Celeste,” sold in September 1960 at the Continental Trading Company in Norfolk, West Virginia. William Salisbury, Onondaga’s president, penned an angry letter to J. T. Mizuno at the Japanese Pottery Design Center to ask if the center even bothered living up to its purpose since copies continued to run rampant in the United States, despite patents and copyrights. Mizuno apologized, explaining that the latest cases resulted from a misunderstanding and consisted of a one-time shipment with no further inventory in existence. He also acknowledged the widespread copying problem, and assured Salisbury that the center issued stern warnings to the local factories not to copy American patterns.Footnote 37

Nevertheless, just months later, Salisbury opened a newspaper and found an advertisement for a copy of his “Woodbine” pattern for sale. He advised his salesmen to reassure Onondaga’s dealers that the copy would be dealt with and asked them to keep an eye out for a physical set of dinnerware that could be used to file another lawsuit, even offering a $10 reward for the first salesman to bring in a plate. He also registered a complaint with the American consulate, who met with representatives of the Design Center in the fall. They maintained that an American distributor had requested these items and had provided a copyrighted design for their order’s decoration, and the factories merely followed the directions of their client. They went on to claim that the distributor gave them false information by implying that Syracuse China approved the copied pattern and authorized the Japan Pottery Inspection Association to allow the shipment to go through. They expressed the center’s regrets following the misunderstanding, while the consulate urged them to use greater caution when approving designs that could contain copyrighted images.Footnote 38 The “Woodbine” incident appears to be the last major copying disagreement with Japan, likely due both to the better copyright enforcement by the center and to the fact that most American earthenware and china dinnerware manufacturers closed their doors in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Appeals to Consumers: The Buy American Campaign and Its Failure

With the U.S. government’s indifference on both tariff policy and relief petitions, pottery officials knew that they could not rely on the their government to help their small industry in the fight against imported china. They now appealed to their customers’ and employees’ patriotism and concerns with local jobs. As far back as 1914, the USPA considered a “Made in America” campaign as a way to strengthen their industry against European ware. By the time Japan emerged as a threat in the 1920s and 1930s, Thomas Anderson, USPA’s president, further reasoned, “By presenting a united front we might accomplish a lot in our fight to hold, in part at least, the home market for home workmen and manufacturer.”Footnote 39 Historian Dana Frank traces the “buy American” tradition to the Boston Tea Party, and notes that it relies on grassroots support to foster patriotism in the economy. Frank goes on to identify several key periods of the buy American sentiment, often corresponding with larger global issues. In this way, those who bought goods from their home nation rejected the globalized nature of the economy in favor of a centric approach that participants hoped would alleviate the greater problems. The second major wave of buy American sentiment broke out just as the Great Depression exacerbated unemployment in the United States. News magnate William Randolph Hearst led a new movement to buy American-made goods in the hope of creating jobs during the Depression, even going so far as to get Congress to pass a Buy American Act in 1933. Hearst’s movement also possessed a darker side: intertwined with the patriotism of buying American was an undeniable racism against the producers of imported goods, specifically the Japanese and later the Chinese.Footnote 40 This not-too-subtle racism would persist in many of the campaigns launched by the pottery industry as well.

The USPA and manufacturers’ joint response to Japanese pottery took on two forms, both firmly rooted in the tradition of buying American. The first attempt at a buy American campaign on the part of manufacturers took place in 1933 under the leadership of Wells through the USPA, who put together a public relations committee to solve the industry’s lack of a public presence. As part of publicizing American-made china, the committee sponsored a “Buy American” display that ran in nine major department stores throughout the country in February and March. The NBOP also contributed to the display by providing staffing and paying a portion of the costs. The store displays drew attention in their respective cities, but the cause needed a larger presence in order to sway national opinion.Footnote 41 Around the same time, former tariff consultant Captain F. X. A. Elbe grew frustrated with the influx of imports and the lack of action at the government level. Drawing on the success of a similar movement in Great Britain, in 1935 he and a group of like-minded businessmen (including Wells) founded the Made in America Club, a nonprofit volunteer organization designed to convince consumers to buy goods produced in their own country in respect for the American democratic way of life (Figure 1). The Made in America Club looked for support from a variety of sources, including Congress, raw materials suppliers, and as many different business leaders as possible. However, at its heart, the club sought to reach consumers directly. To do this, it printed up stickers and brochures, distributed buttons and license plates, circulated a monthly newsletter, and put displays in major department stores that showcased the quality and variety of American-made goods. Any consumer could belong to the club by signing the following agreement: “I hereby pledge myself to buy, so far as it is practicable, only products made or grown in America, by American labor and thereby give work to my fellow Americans, and maintain the American standard of wages.”Footnote 42

Figure 1 Flier for the Made in America Club, c. 1940.

Source: Courtesy Kent State University Special Collections and Archives.

Potters held a prominent place among the diverse industries represented in the Made in America Club in its attempt to curtail Japanese inroads to the American dinnerware market. Representatives from Scammell China, Sebring Potteries, and Hall China sat on the club’s advisory council, and in 1939 Wells took over the role of president for the entire organization, and Elbe served as its managing director. Wells felt the need to get all of the country’s potteries on board in support against imports. As a member of the USPA’s executive committee for much of the 1930s, Wells also got the trade association to pledge a yearly stipend of $3,600 for the club and to prominently recognize its activities. In 1936 and again in 1939, he organized membership drives, first for the manufacturers and then, in conjunction with the NBOP, for all unionized pottery workers. By the end of the drive, the majority of the leading plants in the East Liverpool area, the East Liverpool Chamber of Commerce, and upwards of 95 percent of union members belonged to the club and openly expressed their commitment to buy American goods in protection of their livelihoods.Footnote 43

Under Wells, the Made in America Club continued its outreach efforts to spread the message of supporting American business. Many of the members shared the common trait of being small-scale industries in the United States. While their trades (pottery, lace and other textiles, specialty foodstuffs) appeared insignificant as compared to steel or automotives, they nevertheless filled a vital need for the market while being constantly at risk of replacement by foreign-made products. The club worked to publicize their contributions through continuing the “Buy American” displays that started with pottery and spread to a variety of items.Footnote 44 The club also found success petitioning at the state level. In July 1938, Ohio Governor Martin L. Davey proclaimed that September 3–10 would be “Buy American Goods Week” throughout the state. Other local-level proclamations were made in other cities, including East Liverpool and Lima, Ohio; Trenton, New Jersey; Westerly, Rhode Island; and Cascade, Montana. That November, the club cosponsored a CBS radio broadcast on the history of the American pottery industry. Listeners around the United States heard the stories of Lenox China and Homer Laughlin China narrated by Arthur Wells (brother of Joseph, and himself vice president of the company) and Duffy. The broadcast ended with a personal plea from Duffy to support America’s working men and women by avoiding buying imports made with slave wages.Footnote 45

The Made in America Club functioned with a remarkable level of cooperation between labor and management in order to protect their industry against imports. Duffy became heavily involved with the club as both a recruiter and as the voice for the employees whose jobs depended on buying American. He made regular appearances at the club’s annual meetings in New York City, where he gave speeches outlining the importance of the movement from the perspective of workers. He cited the long record of peaceful negotiations between the union and the USPA as all the more reason for them to band together against imports. Duffy’s efforts paid off in May 1940 when the group, renamed the Made in America Foundation to cement its nonprofit status, named him as a vice president.Footnote 46 Unfortunately, by the time Duffy came on board in an official capacity, the organization had already entered its final decline. Wells noted years later that it continuously struggled to survive financially despite the yearly contributions from the USPA and others. Distributing free premiums, printing a free newsletter, and other promotional activities strained a nearly nonexistent budget, and despite thousands of pledge cards, the membership achieved very little toward furthering the Made in America cause.Footnote 47 Elbe’s presence held the struggling organization together, so the final blow came when the captain got his orders to report for active duty in November 1942. With Elbe gone, the foundation faded away before the end of World War II.

Even as the manufacturers took part in the originally named Made in America Club, the NBOP sought to create its own grassroots movement to protest against Japanese pottery. At the 1937 national AFL convention in Denver, Colorado, Duffy, who was there as a representative for the AFL-affiliated NBOP, introduced a resolution that called for a boycott of all Japanese-made goods. The resolution passed favorably, and the AFL unions agreed to participate and to support the pottery workers.Footnote 48

Another important source of support came from management. Knowing that pottery workers often made up their first customers, pottery heads worked to support employee efforts in protecting their livelihoods. During the AFL convention, the USPA wired Duffy to encourage his proposal and promised full cooperation in a boycott. A few weeks later, the association released a statement to the press, outlining once again the relationship between the USPA and the NBOP going back to 1899—longer than any other trade’s collective bargaining agreement—and their record of generally peaceful labor negotiations, the high cost of American labor as compared to Japan, the increase in the number of Japanese-made goods in the United States over the past ten years, and the inability of the current tariff to alleviate the problem. In closing, the USPA remarked that the union successfully secured a resolution calling for an all-union boycott of Japanese goods and publicly announced its full support of it.Footnote 49

Within weeks of the passage of the resolution, NBOP began planning to put the boycott into action. The first step took members door to door throughout the East Liverpool district to explain the boycott and to obtain signed pledges from local residents to buy only American-made goods. The second step involved visiting local shops to check for any Japanese-made merchandise. If NBOP members found foreign products for sale, they either convinced the retailer to cease carrying the merchandise or, in some cases, bought out the stock so it could be destroyed. Complying retailers received a window sign showing that they supported both the boycott and American jobs. The culmination of the boycott drive came in a massive rally in East Liverpool on December 13, 1937, for which organizers planned a parade, a bonfire, and a slate of speakers. AFL president William Green adjusted his schedule to come to Ohio for the big event, and USPA contacted LIFE Magazine for coverage, which resulted in a photo of the event in the December 27 edition.Footnote 50

The boycott rally kicked off at 7:30 p.m. on a cold night, starting with a massive parade through the streets of East Liverpool. As many as twenty-five hundred men, women, and children partook in the parade, including riding on the dozens of floats and in decorated cars, and playing in marching bands. Pottery executives walked the route alongside their employees, and several of the plants sponsored their own floats. In addition to NBOP members, representatives from other labor unions (including brewers, painters, and truck drivers) also marched in a gesture of solidarity. All the floats and cars contained some variation of the buy American theme, both serious calls and more humorous messages. One car, decorated as a coffin, proclaimed the death and burial of Japan in the United States. Another portrayed a stereotypical Japanese rickshaw with the slogan “The Mikado’s Last Ride though This Town” emblazoned on the side. For many, the highlight of the evening surely arrived with the massive bonfire at the top of Deidrich Hill, the highest point in the city. NBOP members collected foreign-made merchandise from more than 100 local stores, and they set the pile ablaze at the conclusion of the parade, destroying $20,000 worth of products.Footnote 51

After the fire reduced to embers, the crowd moved downtown to the Ceramic Theater for the final portion of the rally: the keynote speeches by Elbe, Duffy, Wells, and Green. Duffy called the buy American movement “the essence of patriotism,” because it perfectly adhered to the Constitution’s promise that power rested in the will of the people. He also compared the United States’ standard of living with that of Europe and Asia, noting that American workers not only supported their families but also enjoyed a high enough wage to purchase luxury items. However, if foreign goods continued to chip away at the home market, U.S. producers would have no choice but to lower the standard of living in order to compete, thus erasing decades of workers’ progress. In his keynote, Green also described the poor working and living conditions of Japan as well as criticizing Japan’s attack on a Chinese ship just days before. In closing, Green promised the continued support of more than four million AFL members and twenty million other supporters to drive all foreign products from American stores.Footnote 52

The rally gained national attention, even if the Crockery and Glass Journal called it “a gesture of violence.”Footnote 53 Following a week or two of publicity, the question turned toward how to keep that momentum going into 1938 and beyond. The trade journals suggested either agitating for tariff reform or an embargo on Japan, which public opinion seemed to favor in light of increasing Japanese military aggression. The USPA continued to support the boycott, and Joseph Wells noted it succeeded in getting several major discount retailers to stop the sale of Japanese products. Meanwhile, Duffy and the NBOP decided to take their show on the road to hold boycott rallies in other struggling pottery towns. On April 1, Joseph Wells spoke at a parade and bonfire in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, followed the next evening by a parade and rally in Paden City, West Virginia, which was attended by both Duffy and Senator Rush Holt, and even included the burning of a Japanese potter in effigy.Footnote 54

While the boycott rallies and buy American drives brought publicity to America’s potters, their tangible value is up for debate. At the January 1938 Pittsburgh China and Glass Show, less than one month after the first Liverpool rally, Rhead, the art director at Homer Laughlin, dismissed the boycott as largely a failure. He felt that most chain stores, even those that pledged not to purchase Japanese goods, still had enough remaining inventory to keep selling foreign product for weeks or even months to come. He also reasoned that even if they kept their pledge not to sell Japanese, cheaply made pottery and other products from countries such as Czechoslovakia still remained on the shelves to attract bargain-minded consumers. Dana Frank notes that buy American movements often fall short for one very basic reason: consumers rarely notice or care where the products they purchase come from; they mainly care about price.Footnote 55 A buy American campaign could work in the hometowns of these potteries; however, no national movement took off, but remained regional in Ohio and West Virginia. If inferior products from foreign nations cost less than domestically manufactured, a price-conscious housewife was more likely to choose it despite the big-picture consequences she likely knew little about.

Rhead concluded that innovation in shape and design, not boycotts, held the key to getting the public to purchase American-made china, but many of his contemporaries failed to heed his advice.Footnote 56 His concern illustrates another reason why imports gained a foothold over American dinnerware. The majority of companies did little to set their products apart as particularly special when compared with Japanese or other imported ware. American pottery manufacturers always struggled with advertising: individual plants promoted their own goods, but the diversity in the industry as a whole between earthenware, dinnerware, and hotelware prohibited any unified brand creation that could battle Japan on a large national scale. Consumer historian Steven Waldman suggests that when faced with a multitude of similar products, the “tyranny of choice” leads to both a decline in brand (or in this case national) loyalty as well as a tendency to make consumption purchases based on impulse rather than rationality.Footnote 57 American buyers of china, assumed to be housewives or newlyweds, bought one or two sets of china for their homes. Their purchase decisions were usually based on the most affordable set that appealed to their taste, because they rarely were given reason to act otherwise. With many Japanese patterns looking similar or even blatantly identical to American sets and no strong publicity on the part of American manufacturers as a whole, price won out over producer. Additionally, as a casual lifestyle took hold in America in the 1950s and 1960s, emphasizing the convenience of TV dinners, dining out, and quick stops at fast food joints, the traditional meal served on good china mattered less and less. Families that once would have selected high-quality dinnerware for their homes now made do with cheaper ware. If a piece broke, a replacement was inexpensive, and an entire set could easily be purchased to match current fashion. Increasingly, American families forsook china altogether and dined instead on plastic plates or disposable products when the occasion permitted.

Appeals to Each Other: The Crane China Controversy and the Collapse of the Dinnerware Market

With customers not willing to sacrifice cost for quality, and without the guarantee of local jobs, pottery heads instead tried to appeal to one another to strengthen the dinnerware branch of the industry. However, manufacturers could not agree on a single position, but instead attacked one another’s approach to the issue. One of the most serious clashes came with the opening of a new dinnerware plant outside the mainland United States. In 1947 Earl Crane, a majority stockholder in the Iroquois China Company, in Syracuse, New York, opened a pottery plant in Puerto Rico to make Crane China. The U.S. government provided Crane with a twelve-year tax abatement and modernization funds while Iroquois provided a ready network of dealers to distribute the new ware. Most distressing of all to other potteries, Crane could take advantage of Puerto Rico’s low wages and pay his workers $0.38 per hour for the same job American workers performed for nearly four times as much and not have to pay Social Security taxes. As a final blow, the plant’s location in Puerto Rico excused it from tariffs as it operated in an American protectorate.Footnote 58 In short, Crane could produce vitrified dinnerware at import prices without the penalties paid by those foreign companies.

American manufacturers saw Crane China as a threat from the start, because they could not match the wages that a Buffalo China executive dubbed “slave labor.”Footnote 59 Orders dropped as dealers in need of white undecorated ware turned to Crane’s exceptionally low prices. In a pattern reminiscent of the 1930s, management and labor united in an effort either to close Crane or force it to pay American wages to its employees. Throughout 1949 and 1950, Duffy made several appearances in Washington, DC, along with representatives of the Vitrified China Association (VCA) to argue for a higher minimum wage in Puerto Rico.Footnote 60 The efforts to raise the minimum wage stalled; meanwhile, the Crane situation caused a larger rift among American potters. Because Iroquois belonged to the VCA, its ownership of Crane caused friction among members who accused it of damaging the industry as whole. The hard feelings eventually led Iroquois to leave the VCA, but the tension remained. Crane complained that despite the low wages, his company continued to struggle, leading him to want to sell it in fall 1950. Sterling China, of Wellsville, Ohio, emerged as the buyer, and it took over operations the following year, renaming the business Caribe China. Because Sterling not only belonged to but also held leadership positions within the VCA, the trade association dropped the push for a higher minimum wage in Puerto Rico, and the remaining members settled into an unhappy acceptance of the plant.Footnote 61

Meanwhile, Japan’s imports continued to increase yearly until it held more than 80 percent of the American dinnerware market by 1960. Soon, other foreign producers joined the Japanese. During the 1967 contract negotiations between the USPA and IBOP, the trade association noted with alarm the entrance of Brazil, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Poland, Taiwan, and Hong Kong into the pottery import business. Hong Kong especially alarmed USPA officials, because it allowed a portal for the importation of pottery made in communist China. Everson Hall, of USPA, noted, “If Japan’s wages are 46 cents per hour, China’s must be next to nothing.” That same year the trade paper Home Furnishings Daily mused that China’s impact on the pottery market could prove even more significant than Japan’s in time, a concern that would turn out to be true by the end of the century.Footnote 62

With the market for American dinnerware eroding, the trade associations of the industry also began to decline. USPA experienced a steady downsizing in the years following World War II. Part of this came as member firms went out of business when they could no longer compete with foreign imports. More importantly, USPA could no longer fulfill many of the needs of the surviving potteries in the United States. Earthenware producers chiefly created USPA to suit their own purposes, and even though hotel and vitrified china plants joined over the years, they began to feel that their needs could be better met in other organizations, such as the Vitrified China Association and later the American Restaurant China Manufacturers Association. By the end of the 1970s, with only Homer Laughlin China and the Hall China Company as remaining members, the organization quietly dissolved.Footnote 63

Trade associations were not the only organizations to fold in the face of the import problem. With Japan alone cornering more than three-quarters of all production, and with countries such as China entering the trade, dinnerware manufacturers in the United States simply could not survive in large scale. While Lenox China and Pickard China thrived due to their hold on the very high end of the market, the makers of everyday china and earthenware rapidly shut their doors from the 1950s onward. Other potteries that dealt in both home and hotel china felt compelled to drop their increasingly unprofitable dinnerware lines. Syracuse China became the first casualty. James Pass, when he was president of Onondaga Pottery, dreamed of a marquee line of fine china, named Syracuse China. Over time, the line became so synonymous with the company’s identity that Onondaga changed its name to reflect the china’s popularity. Nevertheless, by the late 1960s, Syracuse China, the company, simply could not justify Syracuse China, the product. Dinnerware sales continuously declined at the plant; by 1969, it accounted for less than 20 percent of total revenue, and actually lost the company money. On June 11, 1970, President William Salisbury called together the employees of the Fayette Street plant, which produced the Syracuse China line, to announce its closure and the discontinuation of all fine china production. Afterward, Syracuse China dedicated all of its resources to hotelware at its Court Street location. Salisbury initially estimated that only 270 or so employees, most with less than three years seniority, would lose their jobs, but the number eventually exceeded three hundred as the Court Street plant simply could not absorb so many workers from the Fayette plant.Footnote 64

Homer Laughlin became the next home china line to go. The company created the “Best China” hotel line in the late 1950s, and dedicated increasing attention to it as its dinnerware sales lagged. Fiesta, the hallmark of the company, failed to hold customers’ attention the way it did in the 1930s and 1940s, despite the introduction of new colors more in line with contemporary taste. In a last ditch effort, Homer Laughlin restyled the entire line in 1969, dubbing it Fiesta Ironstone and introducing the new colors turf (avocado green) and antique gold to go along with the reintroduced original red (now called mango).Footnote 65 The colors appealed more to 1960s design and saved the company money, because all pieces fired at the same temperature rather than the variety of fires needed for original Fiesta. The number of pieces also shrank, with serving pieces, such as casseroles, bowls, and even salt and pepper shakers, made only in antique gold. However, even the restyling of the line could not spark interest in the now woefully outdated art deco shapes. In 1973 the company ceased production of Fiesta and all other remaining home lines, choosing to focus solely on its institutional production.

Castleton China, Shenango’s fine china line, was the last to cease production. Years of declining sales made Castleton unprofitable by the late 1960s. In 1967 the first major scaling back occurred when the company cut the number of available shapes and eliminated nearly all serving pieces and specialty items, such as cream soup bowls. Many of the patterns shifted away from open stock as well, although the company promised to provide continued support of their retired patterns through on-demand runs of pieces and patterns specifically ordered by consumers as replacements.Footnote 66 After the Interpace Corporation purchased Shenango China in 1968, it lost interest in supporting the Castleton line, choosing instead to focus on Franciscan China made by Gladding-McBean, its subsidiary. In 1974, Interpace announced the cessation of Castleton China for the home, and following a set of commemorative presidential china plates in 1976, all fine china operations ceased at Shenango.Footnote 67

Japan Enters the Hotelware Market and the Industry Goes to War

The hotelware industry previously avoided the brunt of damage from imports due to a gentlemen’s agreement between the Japanese Pottery Exporters Association and a number of American manufacturers, which stated Japan would prohibit the export of hotel china if American firms toned down their criticism of exports of china and earthenware for the home. This agreement worked for a number of years but, interestingly, an American firm, not a Japanese one, looked to break the contract and import Japanese-made hotelware into the United States. At the August 1960 meeting of the American Restaurant China Manufacturers Association (ARCMA), George Zahniser, president of Shenango China, proposed a plan for American firms to contract with Japanese companies to import hotelware into the United States. Zahniser expressed concern that domestic manufacturers could never keep up with the low wages of Japan. For him, if American potters could not beat Japanese prices, then they must join them in importing ware to sell in the United States.Footnote 68 Needless to say, many other manufacturers strongly opposed his plan. Weeks later, Foster T. Rhodes, vice president at Onondaga, and the company’s ARCMA representative, dictated a harsh letter to Zahniser, pointing out that Shenango’s workers did not belong to the IBOP, thus lowering the amount of wages his plant paid out of its profits. Rather than suffering, Shenango must hold the advantage in the hotelware industry and could not possibly be doing as poorly as Zahniser claimed. Furthermore, Rhodes warned that offering Japan entry into the U.S. hotel market would devastate the industry; Rhodes promised Onondaga would continue to compete fairly no matter the circumstances. Nevertheless, Zahniser continued with his plan and signed an agreement with Nippon Kohitsu Toki for the manufacture of twenty-five thousand dozen pieces of hotel china to be sold in the United States under the Shenango name and through their authorized salesmen. Zahniser’s plans also attracted the interest of Jackson China, in Falls Creek, Pennsylvania. Not long after Zahniser negotiated his deal, Saul Weingrad, vice president of Jackson, also traveled to Japan to seek a similar arrangement.Footnote 69 Gould, of Buffalo China, tried to dissuade Zahniser from the contract, stating, as had Rhodes, that he had overestimated Shenango China’s struggles and, in fact, it carried on better business than most other plants. He closed by condemning importation as “a terrible idea which is liable to wreck everything and everybody, yourself included.”Footnote 70

While Onondaga China and Buffalo China headed up the opposition through ARCMA, the controversy deepened in October when Iroquois China not only agreed with Zahniser’s idea but also entered negotiations with a Japanese firm, Narumi Seito. While Rhodes accused him of worsening a dire situation, Iroquois China’s president S. F. Cohen defended the plan as “an up-to-date merchandising idea.” He blamed ARCMA members of spending too much time whining and not enough time building up their own products. Rather than the dire situation Rhodes warned, Cohen instead argued his and Zahniser’s approach would secure the future of their firms.Footnote 71 ARCMA continued its protest by going straight to the Japanese Pottery Exporters Association. Sterling China’s president, William Pomeroy, wrote to that association’s president, Shizuo Dohke, in protest of the claim in Home Furnishings Daily that he received no argument in opening the market for Japanese china. Pomeroy assured Dohke that many pottery firms remained opposed to breaking the agreement and promised to involve the U.S. Department of Commerce and U.S. State Department to prohibit the importation. Finally, ARCMA threatened a boycott of all Japanese imports if hotel china entered the United States.Footnote 72

In response to the pressure, the association decided to abandon Iroquois’s and Shenango’s agreements in January 1961. Dohke traveled to the United States to gauge interest in exports, and found the ARCMA hopelessly split, with Shenango and Jackson China in favor and Onondaga in opposition. Iroquois China, the other concerned party, never belonged to ARCMA, choosing to distance itself from trade associations following the Crane China controversy. With the association split, Dohke agreed reluctantly to uphold the ban for the time being. For Rhodes and Ray Cobourn, vice president at Onondaga, the disunity in the ranks of American producers signaled trouble. To them, hotel manufacturers narrowly avoided disaster with the decision to continue the ban, but Cobourn worried that Shenango’s continued insistence on a quota of imports would lead the Japanese to disregard the ban as no longer necessary. Onondaga’s official position remained that even a small quota of imports would displace an equal amount of American-made product, which would soon spiral out of control until the situation for hotelware equaled that of earthenware and dinnerware in gravity.Footnote 73

Meanwhile, at Shenango, W. P. C. Adams took over leadership of the Castleton China division in January 1961. Castleton’s decreasing sales signaled a need for revitalization, in addition to a need to retire patterns and shapes in order to streamline production. Adams called for a new low-cost line. William Craig McBurney, director of Design, crafted a new shape called Independence Ironstone, which took advantage of a renewed interest in American colonial décor. The design was octagonal with bold patterns, and it sold for only $9.95 per place setting. Despite its Americana influence, Independence Ironstone would not be made in the United States. To keep down costs, Adams contracted production to Nippon Toki Kaisha, in Nagoya, Japan. Although Shenango could not import hotelware, it could successfully import the Castleton line starting summer 1961.Footnote 74 After Independence Ironstone, Shenango continued to pursue an additional contract for hotelware. In fall 1961, Zahniser again brought up the plan to ARCMA, promising that imports would be kept to a quota, which he estimated at seven hundred thousand dozen pieces. This could be split among all interested companies. Rhodes again blasted Zahniser in a statement to the group, questioning whether the Japanese Pottery Exporters Association would actually agree to a quota and when it would demand more. To him, any quota opened the door to unlimited imports, which would displace more and more American production. In time, American producers would fight for a shrinking market, eventually destroying one another and leaving Japanese manufacturers to benefit from the mayhem. Rhodes closed his statement by insisting that all producers needed to stand together and persuade Japan to keep the ban in place.Footnote 75

On November 14 of that year, the industry was rocked with the news that Shenango again secured a contract—this time with Nippon Koski Tsua—to produce two hundred thousand dozen pieces of china for importation to the United States. E. K. Koos, president of Sterling China, sent IBOP President Edwin Wheatley a panicked letter that afternoon, alerting him that the Japanese Pottery Exporters Association not only would approve the importation but also would look to other U.S. potteries to export an additional three hundred thousand dozen pieces.Footnote 76 The news set in place two frantic weeks of industrywide protests, with management and labor again coming together to stop Shenango. Wheatley rapidly fired off letters to the Department of Commerce and other officials in vehement protest, asking the government to stop the deal or run the risk of destroying the industry. IBOP put all of its affiliated potteries, ARCMA, and the USPA on notice concerning the remaining three hundred thousand dozen pieces of the quota, warning if any other manufacturer agreed to accept foreign goods, the union would strike as well as sue.Footnote 77

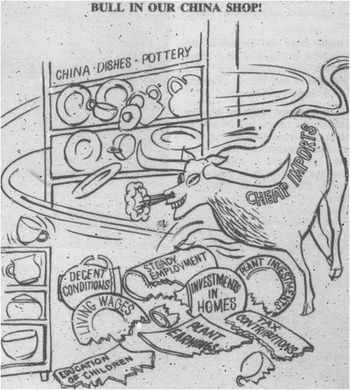

Both the union and ARCMA also wrote in protest to Dohke. They noted that more than 90 percent of American producers objected to Shenango’s import plan, and that dinnerware imports already meant the loss of fifteen U.S. potteries and ten thousand jobs over the past ten years. Both groups continued to plea on a practical level as well, noting that hotelware production involved an entirely different process, which Americans uniquely excelled at but which Japan had no experience. In closing, ARCMA suggested that Dohke consider the waves of negative publicity his association would surely receive by continuing with the plan and the worsening American job losses. Wheatley closed with a stern warning that it faced the wrath of an angry AFL-CIO, whose millions of members would vigorously protest to the highest levels of government (Figure 2).Footnote 78

Figure 2 The Brotherhood of Operative Potters issue a political cartoon commenting on the state of the industry due to Japanese imports.

Source: Potters Herald, February 1962, 5. Courtesy of the Kent State University Special Collections and Archives.

Despite protests, pleading, and threats, the opponents to opening up the hotelware market could not stop the inevitable. The U.S. government sought to further their trade relations with Japan as a bulwark against communism in Southeast Asia; when officials were presented with the protests of American potters, they largely ignored these concerns. Even when Rhodes traveled to Washington, DC, to meet with the Department of Commerce and State Department on behalf of ARCMA, he received little support.Footnote 79 The U.S. government wished to keep friendly trade relations with Japan and viewed any barrier or condition as restrictive if it might move Japan toward communism. The government ultimately controlled imports only with a tariff, which would be drastically cut the following year, leaving hotel china manufacturers to deal with the import problem that destroyed many of their dinnerware counterparts. Interestingly, while Shenango China’s actions set in motion the eventual end of the hotelware ban, no records exist showing if they actually capitalized on it by importation. Manufacture of the Japanese-produced Independence Ironstone continued until the early 1970s, when, as noted earlier, Shenango’s new owner, the Interpace Corporation, phased out Castleton in favor of its own Franciscan China.

Conclusion: Did Potters Spell Their Own Doom?

Between 1950 and 1990, Japan’s overall productivity increased at twice the rate of the United States. Historian David Nye notes that U.S. manufacturers tended to fall behind due to a lack of innovation, or because labor or suppliers resisted change, or from other factors. Over the years, the cycle of stagnation became so difficult to break that companies fell too behind to catch up, and thus often wound up closing or shifting production elsewhere. In the case of Japan, Nye also observes that decades of anti-Japanese sentiment prevented American companies from wanting to adopt the practices of a competitor, even if it would help their own cause. By the late 1960s, more than five thousand Japanese potteries vied for a share of the American dinnerware market, and imports continued to increase at the rate of 10 percent per year.Footnote 80

The presence of Japanese potters cannot be solely blamed for the doom of American dinnerware; the lack of a strong industrial response either to prevent imports or to adapt properly to their presence also played a critical role.Footnote 81 While the Buy American campaigns in the 1930s stirred up patriotic fervor, they never properly addressed the real reasons as to why imports sold in the first place. Manufacturers, and especially labor, simply complained of competitors’ lower wages instead of lowering their own production costs. By the 1960s, they lost nearly the entire dinnerware market; instead of learning from the example, hotelware manufacturers went to war with one another over imports. It is uncertain if Japan would have honored the hotelware quota, but the refusal to even consider it was one of the major factors in Iroquois China’s shutdown only a few months after their contract fell through. While it likely would have lost some domestic jobs, an importation agreement might have saved the plant. While Onondaga, Shenango, and others manufacturers involved with ARCMA each felt they held the industry’s best interest at heart, their failure to agree on a strategy wound up being exploited by exporters.

Finally, the hope that the U.S. government would step in to help the cause of the pottery industry proved unwise, as its response largely mimicked the disinterest it showed in the fights over American tariff policy. When no outside forces came to their aid, as manufacturers and labor had hoped, American potters faded away, leaving only Homer Laughlin (with its subsidiary Hall), Lenox, and Pickard to operate in the United States today, in an industry that once boasted hundreds of plants.Footnote 82 The actions of management were critical for a plant’s survival, so when time, money, and other resources were squandered, the chances of survival dropped considerably. Today, when it comes to foreign imports, business leaders can take a lesson from the pottery industry. Pottery leaders did not collaborate on product or equipment improvement, but instead chose instead to go to war with one another, wasting time and energy that could have been better spent focusing on their own strategies to survive. When they did work together, it was only to agitate for “buy American” campaigns and government assistance, not to create a cooperative strategy on advertising or publicity that could properly convince the American public to choose better quality over price. These actions, then, failed to rescue a struggling industry from low-cost competition, with the result that only those plants that diversified or catered to a niche market were able to survive.