Introduction

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the first line psychopharmacologic treatment for depressive and anxiety disorders across the life span, and their efficacy is supported by multiple randomized controlled trials.Reference Cipriani, Furukawa and Salanti1 Yet, despite their efficacy, more than half of patients experience side effects,Reference Hu, Bull and Hunkeler2 and nearly one in five patients discontinue treatment because of side effects.Reference Motohashi3 In particular, sexual side effects are common (17%-60% of patients) and contribute to medication discontinuation and nonadherence.Reference Hu, Bull and Hunkeler2, Reference Serretti and Chiesa4 Sexual side effects (eg, decreased libido, genital anesthesia, erectile dysfunction, delayed ejaculation, loss of lubrication, anorgasmia, etc.) degrade quality of life and compound the decreased sexual functioning related to depression and anxiety.Reference Baldwin and Foong5 Moreover, these sexual side effects are related to antidepressant-specific pharmacology (eg, anticholinergic effects and nitric oxide synthase inhibition).Reference Serretti and Chiesa4

While antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction is common and problematic, its management differs from other side effects which are often transient.Reference Westenberg and Sandner6 In fact, SSRI-related sexual dysfunction persists in up to 80% of patients.Reference Baldwin and Foong5 Dose reduction can help some patients treated with very high doses; however, for some patients, dose reductions of up to 50% are needed to improve sexual dysfunction.Reference Baldwin and Foong5 Yet, reducing the dose by this much puts patients at risk for subtherapeutic antidepressant exposure, and sexual side effects could still persist.Reference Lam, Kennedy and Grigoriadis7 Other strategies include switching antidepressants, adjunctive antidepressants (with lower risk for sexual dysfunction) Reference Gartlehner, Hansen and Morgan8, Reference Reichenpfader, Gartlehner and Morgan9, and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors.Reference Evliyaoǧlu, Yelsel, Kobaner, Alma and Saygılı10–Reference Nurnberg, Hensley, Gelenberg, Fava, Lauriello and Paine12 However, these strategies have produced conflicting results.Reference Masand, Ashton, Gupta and Frank13, Reference DeBattista, Solvason, Poirier, Kendrick and Loraas14 Thus, despite multiple clinical strategies and intervention studies, clear, evidence-based guidelines and systematic treatment comparisons for antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction are lacking.

With these considerations in mind, we systematically reviewed studies of treatments for antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. We sought to summarize strategies for antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction and to perform a network meta-analysis to compare these treatments (primary outcome: the Arizona sexual experience scale [ASEX]).

Methods

Identification and selection of studies

A literature review of the national library of medicine (PubMed) and the federal clinical trials registry from 1985 to September 2020 (search terms in Supplemental Table 1) was completed by two authors (MJL and JRS). The references of all eligible studies and review articles were searched for additional trials. All clinical trials that evaluated a specific intervention for antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction use were selected for further analysis. Trials were initially reviewed to determine the frequency of reporting for each sexual dysfunction scale. The most common scale was the ASEX, which was selected as the primary outcome for the meta-analysis proper.Reference Elnazer and Baldwin15 We excluded trials of patients with alternative reasons for sexual dysfunction.

Data extraction

Study data and characteristics (eg, publication year, trial duration, sexual dysfunction improvement measures, and dropout rates) were extracted from primary articles and/or clinical study reports into a database (Microsoft Excel).

For categorical response, the following measures were specified a priori (in order of preference): (1) Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scores ≤2 (indicating much improved or very much improved); (2) 50% reduction in ASEX value; (3) Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scores ≤3 (indicating minimally improved, much improved or very much improved); (4) ASEX ≤19 with no individual item score >4 and ≤2 individual item scores of 4; and (5) ASEX ≤10. For sexual dysfunction severity, ASEX scores were utilized. When only baseline and endpoint data were available, standard deviation of the change from baseline was imputed using a correlation coefficient.Reference Higgins, James, Jacqueline, Miranda, Tianjing, Matthew and Vivian A.16

Network meta-analysis

Using a Bayesian approach, we performed a network meta-analysis to compare mean difference in ASEX scores from baseline to trial endpoint using both a single-arm approach (pcnetmeta)Reference Higgins, James, Jacqueline, Miranda, Tianjing, Matthew and Vivian A.16 and placebo-controlled approach (gemtc),Reference Dias, Welton, Caldwell and Ades17 as previously described.Reference Salanti, Ades and Ioannidis18 Pairwise comparisons from each model were made using relative effect tables with sexual dysfunction improvement expressed as mean difference (Diff) in ASEX score with 95% credible intervals (CrI). To assess the likelihood that a given treatment is the best, second best, and so on within a network, rank probabilities were determined and converted to cumulative rank probabilities from which the surface under the cumulative ranking curves (SUCRA) were generated. Then, each treatment model was ranked using SUCRA values.Reference Salanti, Ades and Ioannidis18

Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots for efficacy and tolerability measures and Egger’s tests.Reference Duval and Tweedie19 Study quality was rated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool by two independent reviewers.Reference Higgins, James, Jacqueline, Miranda, Tianjing, Matthew and Vivian A.16 Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran Q, I 2, and

![]() $ \tau $

2. Sensitivity analyses were performed without the treatment the highest SUCRA value treatment and again without the lowest SUCRA value. The quality of evidence was assessed using The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation framework.Reference Puhan, Schünemann and Murad20 Each study included in the meta-analysis was rated as high, moderate, low, or very low quality based on the categories of risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.

$ \tau $

2. Sensitivity analyses were performed without the treatment the highest SUCRA value treatment and again without the lowest SUCRA value. The quality of evidence was assessed using The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation framework.Reference Puhan, Schünemann and Murad20 Each study included in the meta-analysis was rated as high, moderate, low, or very low quality based on the categories of risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.

Results

Included studies and bias

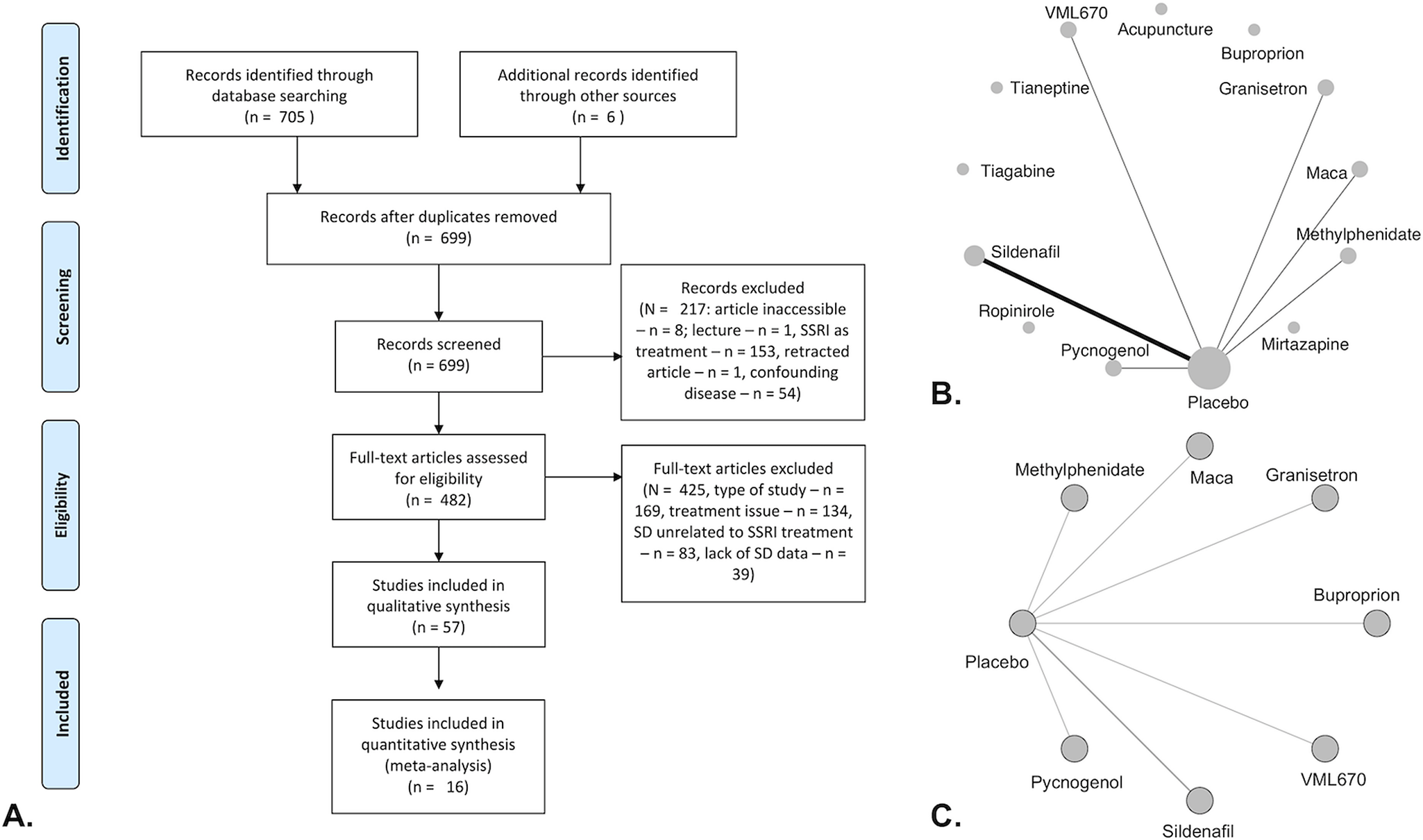

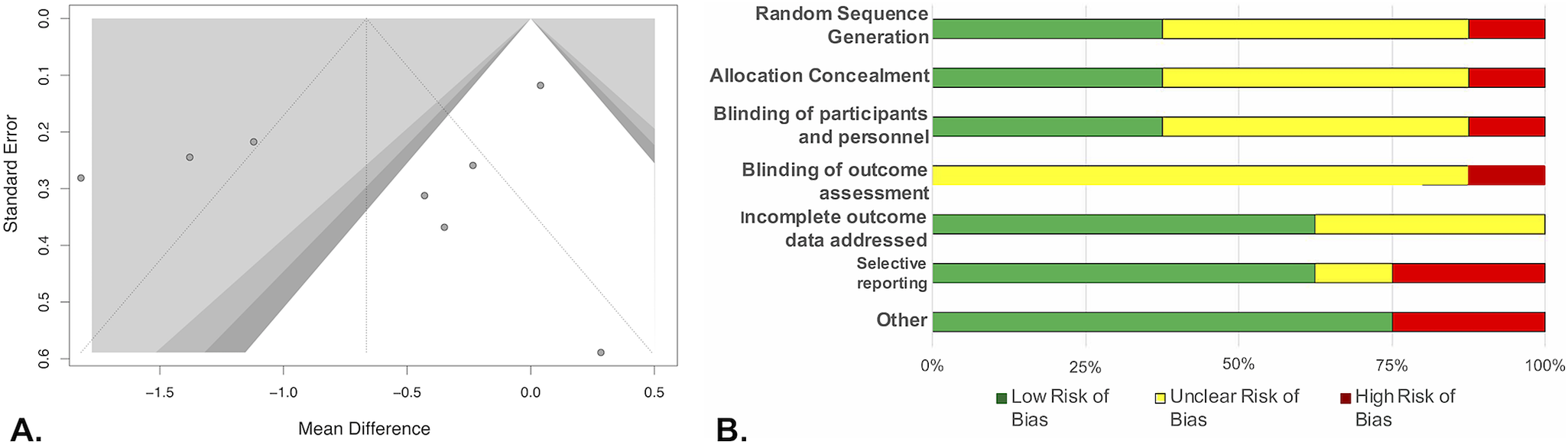

Our search identified 57 studies (Figure 1A), including 31 different treatments. Of these, 16 were used in the network meta-analysis (Table 1 and Figure 1B,C).Reference Nurnberg, Hensley, Heiman, Croft, Debattista and Paine11–Reference Masand, Ashton, Gupta and Frank13, Reference Fava, Rankin, Alpert, Nierenberg and Worthington21–Reference Smetanka, Stara, Farsky, Tonhajzerova and Ondrejka33 A funnel plot of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed that 43% (3/7) of included studies reported nonsignificant results (Figure 2A). An Egger test did not indicate publication bias (P = .31), and heterogeneity for comparisons with placebo were: Q = 66.99 (P < .001), I 2 = 89.6%, and

![]() $ \tau $

2 = 0.4384. Risk of bias was generally low or unclear in placebo-controlled studies included in this meta-analysis (Figure 2B).

$ \tau $

2 = 0.4384. Risk of bias was generally low or unclear in placebo-controlled studies included in this meta-analysis (Figure 2B).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram (A), network plots of all included studies (B), and placebo-controlled trials (C). (A) Full-text articles exclusion reasons: type of study (meta-analysis, guideline, or expert opinion/review—n = 10; reanalysis of prior study data—n = 2, withdrawn or terminated study—n = 2, mechanisms or prevalence study [no active treatment]—n = 155); treatment issues (combined treatment/polypharmacy—n = 2, posttreatment—n = 8, no specification of type of antidepressant—n = 7, patients not on SSRI’s—n = 117); and lack of SD data (includes patients without SD—n = 4, does not include SD data—n = 4).

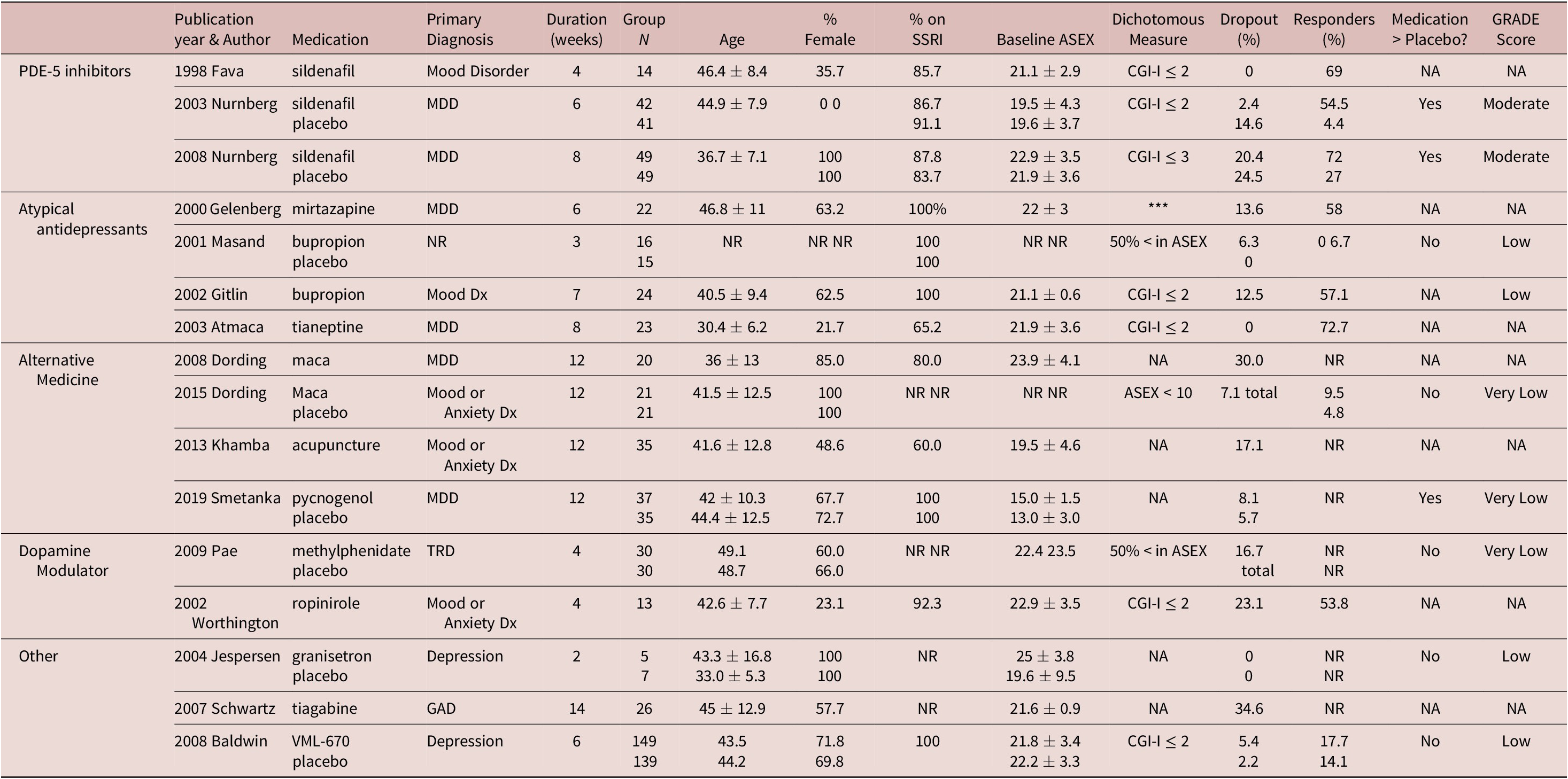

Table 1. Characteristics of included trials.

Medication > Placebo reported in terms of included dichotomous outcome or, if not reported, continuous outcome. All trials were single sites except for the following (number of sites): Nurnberg 2003 (3), Baldwin 2008 (37), Pae 2009 (2). All trials were augmentation trials except for the following replacement trials: Schwartz 2007, Gelenberg 2000, Atmaca 2003.

*** : ASEX total score < 19, no individual item with a score > 4, and no more than 2 individual items with a score of 4

Figure 2. Funnel plots for all placebo controlled studies (A) and Cochrane risk of bias graph (B). (A) Shading of funnel plot corresponds to threshold of significance. Dark gray P < .05, gray P < .025, and light gray P < .01. (B) Unclear risk of bias in the categories of random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, and blinding of outcome assessment was most often due to a study stating it was “double-blind” or “randomized” without providing sufficient details as to how subjects were randomized or who was blinded. Unclear bias was assigned to incomplete outcome data for studies who did not report their dropout numbers by treatment groupReference Dording, Schettler and Dalton26, Reference Pae, Marks and Masand29 or had dropout percentage greater than 10%.Reference Nurnberg, Hensley, Heiman, Croft, Debattista and Paine11

Efficacy and all-cause discontinuation placebo-controlled studies

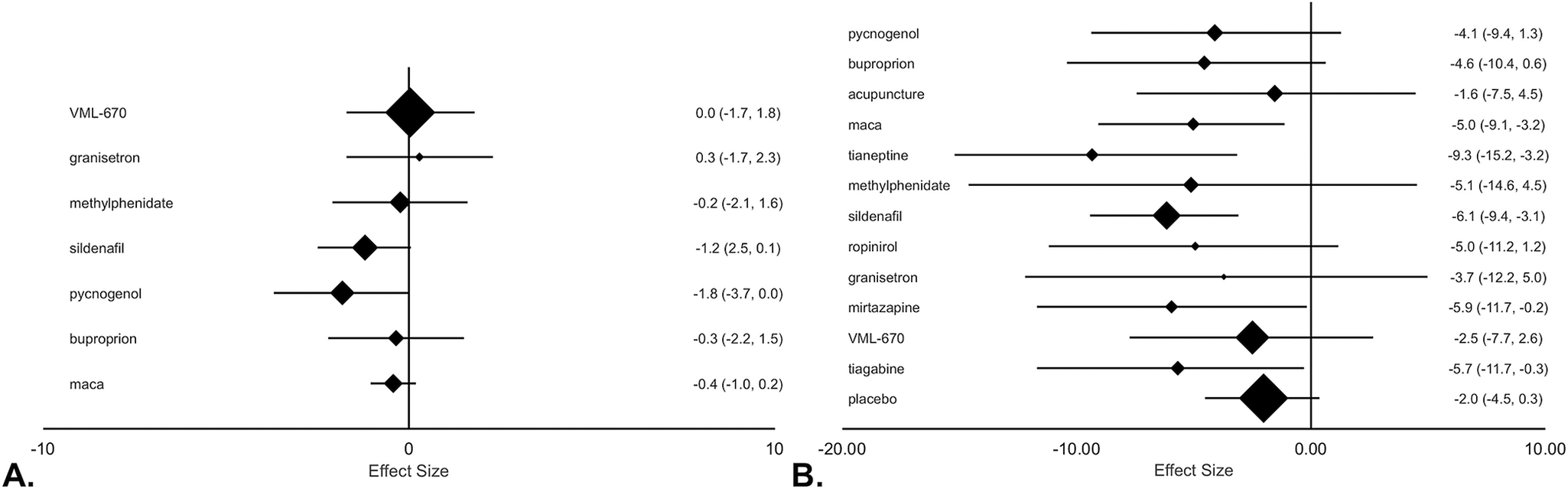

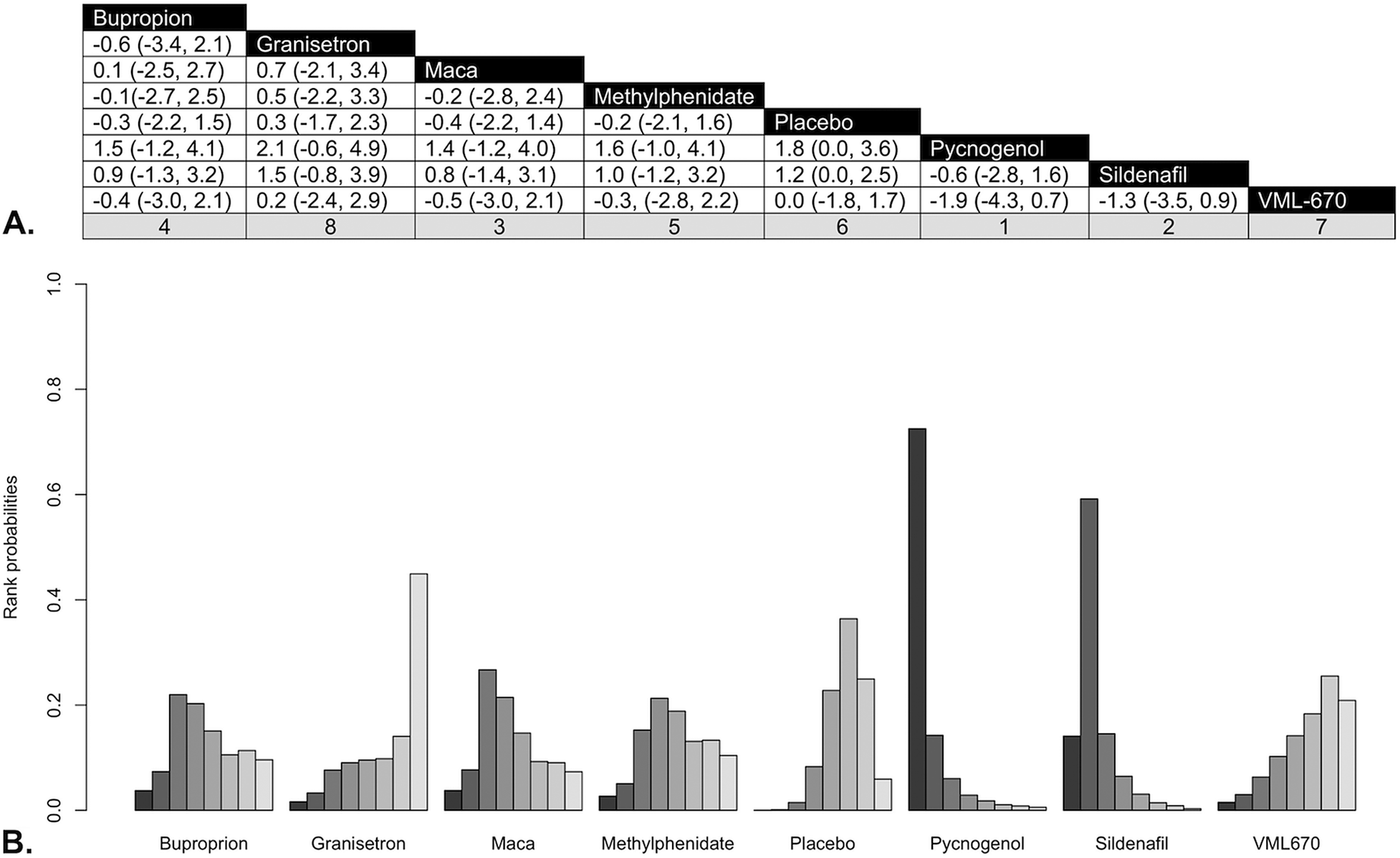

In pairwise comparison of mean differences in ASEX scores by medication compared to placebo (Figure 3A), pycnogenol produced significantly greater improvement than placebo (Diff: −1.8, 95% CrI: −3.7 to 0.0), and sildenafil had the second greatest change in ASEX compared to placebo, but this failed to reach significance at a 5% threshold (Diff: −1.2, 95% CrI: −2.5 to 0.1). Sensitivity analysis showed a stable network and removal of highest (pycnogenol) and lowest (granisetron) SUCRA value treatments did not affect our results (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Forest plot of treatment efficacy for placebo-controlled studies (A) and all included studies (B) based on the Arizona sexual experience scale (ASEX) scores. (A) Effect size based on mean difference of ASEX value between baseline and trial endpoint relative to placebo group with 95% credible intervals (CrIs) in parenthesis. (B) Effect size is based on mean difference of ASEX value between baseline and trial endpoint with 95% CrIs in parenthesis.

Figure 4. (A) Pairwise comparisons of medication classes. (B) Rankogram for treatment efficacy. (A) Rankings according to surface under the cumulative ranking curves (SUCRA) hierarchy appear in column footers, with 1 denoting the most efficacious treatment. (B) Bar heights indicate probability of treatment having that rank for efficacy. Left bar (darkest shade) represents a rank of 1 (most efficacious treatment) with each bar to the right (lighter shading) representing progressive increase in rank (less efficacious treatment).

Single arm studies

In pairwise comparisons of mean difference in ASEX scores by medication (Figure 3B), sildenafil (Diff: −6.1, CrI: −9.4 to −3.1), tianeptine (Diff: −9.3, 95% CrI: −15.2 to −3.2), maca (Diff: −5.0, 95% CrI: −9.1 to −3.2), tiagabine (Diff: −5.7, 95% CrI: −11.7 to −0.3), and mirtazapine (Diff: −5.9, CrI: −11.7 to −0.2) were associated with significant improvement from baseline. However, no treatments were significantly superior to placebo (Diff: −2.0, 95% CrI: −4.5 to 0.3).

The mean dropout rate of 11.1% (interquartile range: 2.3%-17.0%) did not significantly differ between patients receiving active treatment (12.4 ± 11.3) and placebo (7.8 ± 9.8, P = .56).

Atypical antidepressants

In addition to the two trials included in the meta-analysis (1 open-label, 1 RCT), seven studies (open-label

![]() $ \kappa = $

4; RCT

$ \kappa = $

4; RCT

![]() $ \kappa = $

3, N = 426) evaluated bupropion, including two studies involving switching to bupropion and five studies of adjunctive bupropion. In an open-label study, bupropion improved sexual functioning in 81% of depressed adults (N = 39) with fluoxetine-induced sexual dysfunction.Reference Walker, Cole and Gardner34 Similarly, a second open-label study of adults with affective or anxiety disorders (N = 47) and antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction, augmentation with bupropion (75 or 150 mg) PRN 1-2 hours prior to sexual activity or scheduled (75 mg TID),Reference Ashton and Rosen35 improved sexual functioning. However, scheduled rather than PRN dosing (57% vs 19%-26%) produced greater improvement. In a third open-label trial (N = 11), bupropion agumentationReference Clayton, McGarvey and Abouesh36 improved sexual dysfunction. However, subsequent discontinuation of the offending antidepressant further improved sexual functioning. In the fourth study of bupropion augmentation (150 mg/d),Reference Kennedy, McCann and Masellis37 78% of patients reported improved sexual functioning.

$ \kappa = $

3, N = 426) evaluated bupropion, including two studies involving switching to bupropion and five studies of adjunctive bupropion. In an open-label study, bupropion improved sexual functioning in 81% of depressed adults (N = 39) with fluoxetine-induced sexual dysfunction.Reference Walker, Cole and Gardner34 Similarly, a second open-label study of adults with affective or anxiety disorders (N = 47) and antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction, augmentation with bupropion (75 or 150 mg) PRN 1-2 hours prior to sexual activity or scheduled (75 mg TID),Reference Ashton and Rosen35 improved sexual functioning. However, scheduled rather than PRN dosing (57% vs 19%-26%) produced greater improvement. In a third open-label trial (N = 11), bupropion agumentationReference Clayton, McGarvey and Abouesh36 improved sexual dysfunction. However, subsequent discontinuation of the offending antidepressant further improved sexual functioning. In the fourth study of bupropion augmentation (150 mg/d),Reference Kennedy, McCann and Masellis37 78% of patients reported improved sexual functioning.

Adjunctive bupropion has also been evaluated in three RCTs. In the first, bupropion (150 mg bid) produced similar improvements to placebo in adults with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 42).Reference Clayton, Warnock, Kornstein, Pinkerton, Sheldon-Keller and McGarvey38 Interestingly, patients who had more bupropion-related improvement in sexual desire and sexual frequency had greater increases in testosterone concentrations. In the second RCT, adjunctive bupropion SR (150 mg bid, 12 weeks)Reference Safarinejad39 improved sexual functioning compared to placebo in women with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 218). Finally, one negative RCT of bupropion SR (150 mg/d) in patients with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 41) failed to show benefit.Reference DeBattista, Solvason, Poirier, Kendrick and Loraas14

Three studies (92 patients) evaluated mirtazapine (2 open-label, 1 RCT) in addition to the open-label study included in the meta-analysis. Two of these involved switching to mirtazapine and one involved adjunctive mirtazapine. In the first open-label study, mirtazapine augmentation (15 mg/d for 1 week and 30 mg/d for 7 weeks) resolved sexual dysfunction in 49% of adults with remitted major depressive disorder (MDD) and SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 33).Reference Ozmenler, Karlidere and Bozkurt40 In the second, switching to mirtazapine (30-45 mg) in adults with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 11)Reference Koutouvidis, Pratikakis and Fotiadou41 eliminated sexual dysfunction in all patients. In an RCT of premenopausal women with fluoxetine-related sexual dysfunction (N = 148), augmentation with placebo, mirtazapine, yohimbine, or olanzapine for 6 weeksReference Michelson, Kociban, Tamura and Morrison42 did not reveal significant differences among interventions.

In patients with MDD (N = 72) and sertraline-induced sexual dysfunction, randomized, double-blind switching to nefazodone vs restarting sertraline after a 1-week washout periodReference Ferguson, Shrivastava and Stahl43 suggested that sexual dysfunction commonly re-emerged when re-treated with sertraline (76%) compared to switching to nefazodone (26%). In an open-label study of adults with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, trazodone augmentation (Week 1: 50 mg; Weeks 2-4: 100 mg)Reference Stryjer, Spivak and Strous44 also improved sexual functioning.

Two open-label studies (31 patients) evaluated augmentation with the atypical antidepressant mianserin for antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction. In one study, adjunctive mianserin (15 mg/d × 4 weeks)Reference Aizenberg, Gur, Zemishlany, Granek, Jeczmien and Weizman45 produced “marked improvement” in sexual functioning in 60% of men with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 15). In the second study, mianserin augmentation in women with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 16) improved desire, arousal, orgasms, and satisfaction.Reference Aizenberg, Naor, Zemishlany and Weizman46

Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors

In addition to the three trials included in the meta-analysis (1 open-label, 2 RCTs), five studies (open-label

![]() $ \kappa = $

4; RCT

$ \kappa = $

4; RCT

![]() $ \kappa = $

1) evaluated adjunctive sildenafil in 355 adults with antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction. In one open-label trial, males with MDD with SSRI-induced erectile dysfunction (N = 10) received augmentation with sildenafil.Reference Aizenberg, Weizman and Barak47 All patients reported improvement of their erectile dysfunction, and the majority had complete resolution (70%). In a second open-label trial, patients with psychotropic-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 92) received augmentation with sildenafil and showed improvement in all domains of sexual functioning.Reference Salerian, Eric Deibler and Vittone48 However, patients treated with SSRIs had significantly less improvement in arousal, libido, and overall sexual satisfaction compared patients receiving other psychotropic medications. In an open-label trial of women with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 9), adjunctive sildenafil (50-100 mg, 1-hour before sex)Reference Nurnberg, Hensley, Lauriello, Parker and Keith49 improved sexual functioning. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of depressed men with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 142),Reference Fava, Nurnberg and Seidman50 6 weeks of sildenafil produced significantly greater improvement in sexual function and intercourse attempts per week compared to placebo. In a fourth trial—a post hoc analysis of patients with antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction (N = 102) during the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression—sildenafil (50-100 mg PRN) improved libido and sexual drive.Reference Dording, LaRocca and Hails51

$ \kappa = $

1) evaluated adjunctive sildenafil in 355 adults with antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction. In one open-label trial, males with MDD with SSRI-induced erectile dysfunction (N = 10) received augmentation with sildenafil.Reference Aizenberg, Weizman and Barak47 All patients reported improvement of their erectile dysfunction, and the majority had complete resolution (70%). In a second open-label trial, patients with psychotropic-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 92) received augmentation with sildenafil and showed improvement in all domains of sexual functioning.Reference Salerian, Eric Deibler and Vittone48 However, patients treated with SSRIs had significantly less improvement in arousal, libido, and overall sexual satisfaction compared patients receiving other psychotropic medications. In an open-label trial of women with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 9), adjunctive sildenafil (50-100 mg, 1-hour before sex)Reference Nurnberg, Hensley, Lauriello, Parker and Keith49 improved sexual functioning. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of depressed men with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 142),Reference Fava, Nurnberg and Seidman50 6 weeks of sildenafil produced significantly greater improvement in sexual function and intercourse attempts per week compared to placebo. In a fourth trial—a post hoc analysis of patients with antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction (N = 102) during the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression—sildenafil (50-100 mg PRN) improved libido and sexual drive.Reference Dording, LaRocca and Hails51

One RCT of patients with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 20) evaluated augmentation with the phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor tadalafil (20 mg) or placebo.Reference Evliyaoǧlu, Yelsel, Kobaner, Alma and Saygılı10 Tadalafil-treated patients had significantly higher IIEF scores and improved erections and sexual activity (92%) compared to those who received placebo (8%).

Within class switching and dose adjustments

Two studies (open-label

![]() $ \kappa $

= 1; RCT

$ \kappa $

= 1; RCT

![]() $ \kappa $

= 1), involving 494 patients with antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction, evaluated switching antidepressants to escitalopram. Switching to escitalopram (N = 47) improved sexual functioning in 68% of adults, and improvement was more prevalent in patients treated with lower escitalopram doses.Reference Ashton, Mahmood and Iqbal52 However, in a larger trial of adults with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 447), switching to vortioxetine (vs switching to escitalopram) produced greater improvement in sexual function.Reference Jacobsen, Nomikos, Zhong, Cutler, Affinito and Clayton53 Finally, an open-label study evaluated abstaining from weekend doses of SSRI on sexual function in adults (N = 30) with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction.Reference Rothschild54 In this study, withholding short half-life (sertraline and paroxetine) but not long half-life SSRIs (fluoxetine) was associated with improved sexual functioning and did not appear to worsen depressive symptoms.

$ \kappa $

= 1), involving 494 patients with antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction, evaluated switching antidepressants to escitalopram. Switching to escitalopram (N = 47) improved sexual functioning in 68% of adults, and improvement was more prevalent in patients treated with lower escitalopram doses.Reference Ashton, Mahmood and Iqbal52 However, in a larger trial of adults with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 447), switching to vortioxetine (vs switching to escitalopram) produced greater improvement in sexual function.Reference Jacobsen, Nomikos, Zhong, Cutler, Affinito and Clayton53 Finally, an open-label study evaluated abstaining from weekend doses of SSRI on sexual function in adults (N = 30) with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction.Reference Rothschild54 In this study, withholding short half-life (sertraline and paroxetine) but not long half-life SSRIs (fluoxetine) was associated with improved sexual functioning and did not appear to worsen depressive symptoms.

Complimentary/alternative medicine approaches

One RCT involving 50 women with MDD and SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction evaluated vernum (rosa damascene oil) augmentation vs placebo for 8 weeks.Reference Farnia, Hojatitabar and Shakeri55 Sexual desire, sexual orgasms, and sexual satisfaction significantly increased in both treatment groups, but did not statistically differ between groups.

Two RCTs evaluated adjunctive saffron in patients with fluoxetine-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 74). In the first study, women with remitted MDD and fluoxetine-related sexual dysfunction (N = 38) were randomized to adjunctive saffron (30 mg/d) or placebo for 4 weeks.Reference Kashani, Raisi and Saroukhani56 Saffron produced significantly greater improvement in total Female Sexual Function Index scores, as well as arousal, lubrication, and pain subscales, compared to placebo. Desire, satisfaction, and orgasms subscales were higher trending in saffron group, but not statistically different from placebo. In the second study, married male patients with MDD with fluoxetine-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 36) were randomized to either saffron (15 mg bid) or placebo for 4 weeks.Reference Modabbernia, Sohrabi and Nasehi57 Saffron produced significant improvements in total IIEF scores, as well as erectile function and intercourse satisfaction domains, compared to placebo. Orgasmic function, overall satisfaction, and sexual desire were numerically (but not significantly) higher in saffron-treated patients compared to placebo. Erectile function normalized in more patients taking saffron (60%) compared to those who received placebo (7%).

Three studies (open-label

![]() $ \kappa $

= 1; RCT

$ \kappa $

= 1; RCT

![]() $ \kappa $

= 2) evaluated adjunctive ginkgo biloba in adults with antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction (N = 124). In the open-label study, patients with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction refractory to

$ \kappa $

= 2) evaluated adjunctive ginkgo biloba in adults with antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction (N = 124). In the open-label study, patients with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction refractory to

![]() $ \ge $

1 prior intervention (N = 63), received adjunctive ginkgo (40-120 mg bid) for 4 weeks.Reference Cohen and Bartlik58 Eighty-four percent of patients had improved sexual function, although more women (91%) benefited compared to men (76%). In addition, all phases of the sexual response cycle improved. In the first RCT, patients with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 24) were randomized to adjunctive ginkgo or placebo for 12 weeksReference Wheatley59, and similar improvement was observed in both groups. Similarly, the second double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (N = 37) also observed similar improvement with ginkgo and placebo over 8 weeks.Reference Kang, Lee, Kim and Cho60

$ \ge $

1 prior intervention (N = 63), received adjunctive ginkgo (40-120 mg bid) for 4 weeks.Reference Cohen and Bartlik58 Eighty-four percent of patients had improved sexual function, although more women (91%) benefited compared to men (76%). In addition, all phases of the sexual response cycle improved. In the first RCT, patients with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 24) were randomized to adjunctive ginkgo or placebo for 12 weeksReference Wheatley59, and similar improvement was observed in both groups. Similarly, the second double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (N = 37) also observed similar improvement with ginkgo and placebo over 8 weeks.Reference Kang, Lee, Kim and Cho60

Two crossover studies of women (N = 91) evaluated exercise for antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. In the first study, premenopausal women with antidepressant-related hypoarousal (N = 39) engaged in (1) no exercise, (2) exercise 5 minutes prior to, or (3) 20 minutes prior to watching an erotic film.Reference Lorenz and Meston61 Genital arousal was higher in women who exercised, although mental arousal was unchanged. In the second study, women with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 52) were followed for 9 weeks to assess the effects of scheduled sexual activity and exercise on sexual function.Reference Lorenz and Meston62 During the first 3 weeks, patients were sexually active 3×/wk without exercise. During the 3-week crossover phases, patients performed strength training and cardiovascular exercise for 30 minutes to achieve 70% to 85% of max heart rate 3×/wk and then engaged in sexual activity immediately after exercise or waited >6 hours for sexual activity. Sexual desire and orgasm improved but was not statistically different between groups.

In one open-label study, patients with MDD and fluoxetine-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 9), yohimbine augmentationReference Jacobsen63 improved sexual dysfunction in nearly all patients (89%), although 22% discontinued treatment as a result of side effects.

5-HT3 antagonists

In addition to the one RCT study included in the meta-analysis, two crossover studies (open-label

![]() $ \kappa $

= 1; RCT

$ \kappa $

= 1; RCT

![]() $ \kappa $

= 1) evaluated adjunctive granisetron in 55 adults with antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction. In the open-label crossover study, patients on maintenance antidepressant therapy reporting antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 35) received 4 to 6 granisetron (1 mg) and 4 to 6 sumatriptan (100 mg) in a crossover design to be used 1 hour prior to intercourse.Reference Berk, Stein and Potgieter64 Granisetron significantly improved sexual function from baseline compared to sumatriptan. In an RCT (N = 20), both granisetron (1-1.5 mg) and placebo produced similar improvements in antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction.Reference Nelson, Shah, Welge and Keck65

$ \kappa $

= 1) evaluated adjunctive granisetron in 55 adults with antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction. In the open-label crossover study, patients on maintenance antidepressant therapy reporting antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 35) received 4 to 6 granisetron (1 mg) and 4 to 6 sumatriptan (100 mg) in a crossover design to be used 1 hour prior to intercourse.Reference Berk, Stein and Potgieter64 Granisetron significantly improved sexual function from baseline compared to sumatriptan. In an RCT (N = 20), both granisetron (1-1.5 mg) and placebo produced similar improvements in antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction.Reference Nelson, Shah, Welge and Keck65

5-HT1A partial agonists

Two RCTs (N = 104) evaluated adjunctive buspirone in adults with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. In the first, women with fluoxetine-related sexual dysfunction (N = 57) were randomized to buspirone, amantadine, or placebo for 8 weeks.Reference Michelson, Bancroft, Targum, Kim and Tepner66 Sexual function improved in all groups, although “energy” was significantly more improved in patients who received amantadine. In the second RCT, patients with MDD and paroxetine- or citalopram-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 47) received adjunctive buspirone (20-60 mg/d) or placebo for 4 weeks.Reference Landén, Eriksson, Ågren and Fahlén67 Buspirone—compared to placebo—produced greater improvement in sexual functioning (58% vs 30%), and greater improvement was observed in women compared to men; however, differences between buspirone and placebo failed to reach statistical significance.

Others

One randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study of adjunctive ephedrine failed to detect significant differences in sexual functioning (50 mg, 3 week) in women (N = 19).Reference Meston68 Regarding antihistamines, open-label loratadine (10 mg/d, 2 weeks) improved SSRI-induced erectile dysfunction in 55% of patients (N = 10).Reference Aukst-Margetić and Margetić69 In women with antidepressant-induced decreased libido transdermal testosterone (300 mcg/d)Reference Fooladi, Bell, Jane, Robinson, Kulkarni and Davis70 improved sexual satisfaction compared to placebo. However, a placebo-controlled crossover study of women with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 21) failed to detect differences in sexual satisfaction between sublingual testosterone (0.5 mg) + sildenafil, sublingual testosterone (0.5 mg) + buspirone (10 mg), and placebo.Reference Van Rooij, Poels and Worst71 Finally, in men with obsessive–compulsive disorder and antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction (N = 7), open-label cyproheptadine (4-12 mg) 1 to 2 hours prior to sexual activityReference Aizenberg, Zemishlany and Weizman72 improved erectile function in 55%.

Discussion

This comprehensive review of treatments for antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction suggests that while successful augmentation strategies are available (eg, sildenafil and pycnogenol), larger randomized-controlled studies are needed to assess the efficacy of these interventions and to understand heterogeneity in response, predictors of response, and the influence of physiologic variables (eg, age and hormone biostatus). Sildenafil is supported by the most evidence (eight studies, open-label

![]() $ \kappa $

= 5; RCT

$ \kappa $

= 5; RCT

![]() $ \kappa $

= 3, N = 550) and had an impressive change of ASEX compared to placebo in our meta-analysis, though, because of study heterogeneity-related factors, failed to reach significance. This is consistent with treatment effect in multiple individual sildenafil trials. Surprisingly, pycnogenol was the only treatment in our meta-analysis that had a significant change in ASEX score compared to placebo at completion of the trial. However, this treatment was only used in one of the studies with a small sample. Moreover, unlike sildenafil which has a relatively well “understood” mechanism of action, the mechanism of action of this bark extract is less clear, although it inhibits both COX-1 and COX-2 and is a potent antioxidant.

$ \kappa $

= 3, N = 550) and had an impressive change of ASEX compared to placebo in our meta-analysis, though, because of study heterogeneity-related factors, failed to reach significance. This is consistent with treatment effect in multiple individual sildenafil trials. Surprisingly, pycnogenol was the only treatment in our meta-analysis that had a significant change in ASEX score compared to placebo at completion of the trial. However, this treatment was only used in one of the studies with a small sample. Moreover, unlike sildenafil which has a relatively well “understood” mechanism of action, the mechanism of action of this bark extract is less clear, although it inhibits both COX-1 and COX-2 and is a potent antioxidant.

Importantly, trial design played a major role in whether an intervention was deemed successful. In fact, 70% of open-label trials reported a successful intervention but only 22% of placebo-controlled studies demonstrated group differences. In addition, in our meta-analysis, several studies reported increased sexual satisfaction from baseline, but this was not statistically significant compared to placebo. Across psychiatric disorders, high placebo response represents one of the most significant barriers to detecting treatment effects,Reference Huneke, Van Der Wee, Garner and Baldwin73, Reference Mossman, Mills, Walkup and Strawn74 yet the value of placebo response to improvement in the clinic is undeniable. Placebo response in clinical trials and clinical practice has been attributed to various aspects of treatment (eg, therapeutic alliance, diagnostic formulation, treatment expectancy, and benefit of symptom tracking) and, in clinical trials, aspects of study design. We have recently begun to understand these processes in anxiety and depressive disorders. Understanding them in the treatment of antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction could enhance responses.

The mixed results for bupropion—which is generally considered to be a reasonable treatment for antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction—underscore the importance of study design in detecting efficacy. Because sexual side effects are less frequent with bupropion compared to other antidepressants Reference Reichenpfader, Gartlehner and Morgan9, Reference Thase, Haight and Richard75 and all open-label studies (n = 5) suggest benefit, many clinicians view bupropion favorably despite most adjunctive bupropion RCTs failing to suggest benefit (compared to placebo). That being said, it is noteworthy that the largest of these trials, which was conducted in women, had a large effect size. The heterogeneity of samples, measures, and designs highlights the need for larger RCTs of bupropion (augmentation and switching) to better understand its utility as a treatment for antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. In addition, such studies could clarify whether bupropion is a better treatment for women compared to men with antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction.

Given the importance of therapeutic alliance and expectancy on placebo response, clinicians should approach SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction flexibly with special attention paid to patient’s treatment goals and comorbidities. For instance, in patients who prefer “as needed” reversal of sexual dysfunction, there is robust data supporting PDE-5 inhibitors. Conversely, in stable patients wary of polypharmacy a “drug holiday” approach could be useful and is supported by open-label data. However, this approach may have negative or potentially hazardous effects, particularly in patients with more severe affective or anxiety disorders and when medications with short half-lives are used. This could theoretically result in antidepressant discontinuation syndromes or recrudescence of symptoms. Furthermore, the evidence for drug holidays is based on short-term studies; more evidence is necessary to support the use of “drug holidays” as a long-term treatment for antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. Similarly, for patients who prefer a natural product to reverse sexual dysfunction, pycnogenol is a reasonable choice. Even aerobic exercise, particularly in women, could be considered based on the results of open-label trials.

Differences in antidepressant pharmacology subtend differences in side effect profiles when used as monotherapy but could ostensibly mitigate or accentuate side effects when used adjunctively. In general, increased serotonergic activity decreases sexual functioning, whereas increased noradrenergic activity increases sexual functioning.Reference Serretti and Chiesa4 Consistent with this, bupropion monotherapy, which increases dopamine and norepinephrine with no effect on serotonin, is associated with minimal sexual dysfunction.Reference Reichenpfader, Gartlehner and Morgan9, Reference Thase, Haight and Richard75 However, there are conflicting data when bupropion is used adjunctively. When used adjunctively, bupropion may not mitigate the serotonergic effects of SSRIs. Furthermore, differences in the prevalence of sexual dysfunction across SSRIs may relate to pharmacokinetics. Sexual dysfunction is more common at higher SSRI doses and with higher blood concentrations.Reference Baldwin and Foong5 Therefore, SSRI metabolism, which varies considerably between patients,Reference Hicks, Bishop and Sangkuhl76 may contribute to concentration-related antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction.Reference Strawn, Mills and Schroeder77

While this is the largest systematic review and meta-analysis of antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction treatment, there are several important limitations. First, there were no multiarm studies which decreases our ability to compare efficacy. Second, because of variation in trial design and duration, there was substantial heterogeneity among the placebo-controlled studies in our meta-analysis. Third, we included only trials that reported ASEX scores in our meta-analysis to avoid differences across scales; however, this restricted our sample.

Conclusions

For clinicians treating patients with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction, sildenafil has the most robust data, especially in terms of RCTs including both men and women. However, several alternative augmentation strategies may also have efficacy including saffron, granisetron, 5HT2 antagonists, and aerobic exercise. However, larger RCTs are needed to refine the evidence base for treating this common side effect and to identify which individuals would respond best to which interventions. In addition, as a field, we must commit to understanding the risk factors and predictors of antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction in order to prevent or anticipate/preemptively manage antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852921000377.

Disclosures

Dr. Levine has received research support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National of Child Health and Development. Dr. Croarkin has received research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, Neuronetics, Inc., and NeoSync, Inc. He has received grant in-kind (equipment support for research studies) from Assurex Health, Neuronetics, Inc., and MagVenture, Inc. He has served as a consultant for Myriad Neuroscience and Procter & Gamble. Dr. Strawn has received research support from AbbVie, Otsuka, Neuronetics, the Yung Family Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health (NICHD, NIMH, and NIEHS). He receives royalties from Springer Publishing for two texts and has received material support from Myriad genetics and honoraria from CMEology, the Neuroscience Education Institute and Genomind. He provides consultation to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as a Special Government Employee and consulted to Myriad Genetics. Drs. Luft and Dobson have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.