Introduction

Jeffrey Young described early maladaptive schemas (EMS) as enduring patterns composed of memories, emotions and beliefs regulating a person’s behaviour. These patterns are formed during childhood and adolescence based on the frustration of a child’s basic needs with regard to their relation with the object, involving the participation of biological traits such as temperament (Young et al., Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2003).

The concept of schemas in terms of their structure is still evolving. The first theoretically assumed model of schemas (Stein and Young, Reference Stein, Young, Stein and Young1992; Young, Reference Young1990, Reference Young1994) had a hierarchical structure, including 16 schemas grouped into six functional areas (Stein and Young, Reference Stein, Young, Stein and Young1992). The questionnaire measuring these schemas was developed based on statements proposed by Young and on the clinical experience of psychotherapists, and consisted of 205 items. However, empirical verification of this model did not confirm the assumed structure, indicating different numbers of schemas (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Taylor and Dunn1999; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Joiner, Young and Telch1995); nor was the second-order structure confirmed (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Joiner, Young and Telch1995). These studies, however, contributed to the creation of a short version of the questionnaire. Seventy-five items from the long form were chosen, five items with the highest factor loadings for each of the 15 schemas identified by Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Joiner, Young and Telch1995). The research conducted using both long and short versions of the questionnaires confirmed the assumed structure in full (Rijkeboer and van den Bergh, Reference Rijkeboer and van den Bergh2006; Welburn et al., Reference Welburn, Coristine, Dagg, Pontefract and Jordan2002), partially (Calvete et al., Reference Calvete, Estévez, López de Arroyabe and Ruiz2005; Hoffart et al., Reference Hoffart, Sexton, Hedley, Wang, Holthe, Haugum, Nordahl, Hovland and Holte2005) or not at all (Lachenal-Chevallet et al., Reference Lachenal-Chevallet, Mauchand, Cottraux, Bouvard and Martin2006; Samuel and Ball, Reference Samuel and Ball2013). Many other studies in different cultural circles conducted with base or short versions led to similar results: essentially confirmed schema structure and three or four domains.

The result of the validation efforts was the modification of the factor structure in 2003 with 18 schemas and five higher-order factors (Young et al., Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2003), as well as new versions of questionnaires: the long version (YSQ-L3) consisted of 232 items and the short one (YSQ-S3) consisted of 90 items. This model was also subjected to extensive validation studies, conducted, among others, by the authors of the cultural adaptations of the measurement questionnaire (Aloi et al., Reference Aloi, Rania, Sacco, Basile and Segura-Garcia2020b; Cui et al., Reference Cui, Lin and Oei2011; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Choi, Rim, Won and Lee2015; Li-Xia et al., Reference Li-Xia, Chen-Jun, Hong-Zhen, Shu-Ping, Zhi-Ren, Qing-Yan, Jun-Ran and Yi-Zhuang2012; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Cui, Xu, Fu and Wang2017). The results appear to be similar: while the structure of the first-order factors (schemas) is relatively well reflected, the second-order structure (domains) is still unclear (Hawke and Provencher, Reference Hawke and Provencher2012; Kriston et al., Reference Kriston, Schäfer, von Wolff, Härter and Hölzel2012; Kriston et al., Reference Kriston, Schäfer, Jacob, Härter and Hölzel2013; Saariaho et al., Reference Saariaho, Saariaho, Karila and Joukamaa2009; Saritaş and Gençö, Reference Saritaş and Gençö2011). Despite these ambiguities, the five-domain model was successfully used to analyse the relationship between schemas and psychopathology, which allowed for further assessment of its external validity and the model structure.

The desire to create a model that reflects the internal structure as best as possible resulted in its revision. Bach, together with Young and Lockwood, conducted analyses which demonstrated that the most sensible solutions were ones involving two or four second-order factors. On the other hand, the five-factor solution is also interpretable and statistically acceptable and does not undermine the validity of the previously adopted approach (Bach et al., Reference Bach, Lockwood and Young2017a). In the case of the four-factor solution, as some schemas were characterised by factor loadings that simultaneously saturated several domains (cross-loaded to two or more factors), they were classified under the domain in which they appeared in most studies published so far. Therefore, the effect of these analyses is the retention of the number of 18 schemas, but with a significant change in the domain structure.

Although some time has passed since the publication of the latest proposal for the structure of schemas, there are no publications aimed at checking which model better corresponds to the data. In some studies, when adapting the questionnaire, the internal structure of the model is analysed. In the research by Khosravani et al. models of 13, 14 and 15 schemas were tested, as well as models with secondary structure – 3, 4 and 5 domains; 15-factor first-order and five-factor second-order models had more acceptable fits (Khosravani et al., Reference Khosravani, Najafi and Mohammadzadeh2020). However, it should be noted that study was conducted using a questionnaire constructed for a 15-factor structure – YSQ-SF (Young, Reference Young1998). In turn, other studies confirm a four domains structure (Yalcin et al., Reference Yalcin, Lee and Correia2020) or only the primary structure of 18 schemas (Saggino et al., Reference Saggino, Balsamo, Carlucci, Cavalletti, Sergi, da Fermo, Dèttore, Marsigli, Petruccelli, Pizzo and Tommasi2018; Slepecky et al., Reference Slepecky, Kotianova, Sollár, Ociskova, Turzakova, Zatkova, Popelkova, Prasko, Solgajová, Romanova and Trizna2019). Only one study directly compares the four-factor and five-factor solutions, indicating that the four-domain model fits the data better (Aloi et al., Reference Aloi, Rania, Caroleo, Carbone, Fazia, Calabrò and Segura-Garcia2020a). Given the small number of publications and the lack of clarity as to the internal structure of the schema model, the aim of the presented research is to compare the structure of five and four schema domains in terms of their goodness of fit to the empirical data obtained from a healthy adult population. Additionally, to make the study more complete, the analysis of some psychometric properties of questionnaires – the analysis of external validity (convergent and divergent) – is provided.

Method

Participants

The study participants were Polish adults who had responded to announcements in social media or were personally invited (mainly in the case of older people) by trained examiners – psychology students. All participants gave their informed consent to the study. Participants did not receive any reward for participating in the study. Convenience sampling was used, but the sex and age distribution was controlled so that no age group would be over-represented (only people over 55 have a weaker representation – they constitute 7% of the studied sample). Only healthy people without any diagnosed disorders were included in the study. The exclusion criteria, such as psychiatric treatment or prior use of psychotherapy, own or relatives’ current serious somatic disease, and important life changes (wedding, divorce, the birth of the child, mourning, etc.) at the time of the study were checked via short interview made by trained examiners. The exclusion criteria were aimed to measure stable schemas, while during a different highly stressful situation – some schemas may be more active and, inter alia, may have a different significance to the inter-relationship between the schemas than usual. The participants filled out questionnaires in paper form; 2348 fully completed questionnaires of a total of 2500 were qualified for analyses. The removed questionnaires were incomplete (participants withdrew before completing) or raised doubts about the reliability of answers. The subjects were aged 18–81 years (mean=33.89; SD=13.01), and women constituted 54.8%.

Measures

The YSQ-S3 questionnaire (Polish adaptation; Oettingen et al., Reference Oettingen, Chodkiewicz, Mącik and Gruszczyńska2018) was the main measure used in the study. It consists of 90 statements, to which a person responds on a scale of 1–6, where 1 means completely untrue about me, and 6 means describes me perfectly. The statements create a total of 18 schemas, each of which is described by five statements. Sample statements from the questionnaire are: I am worried that people who are close to me will go away or leave me; I am not worthy of love, attention or respect of other people; Most people are more gifted than I am in terms of work and achievement. Despite the fact the long version of the YSQ might be more appropriate for the aim of the study, the short version was chosen. This version is widely used in other psychometric analyses, as well as in therapeutic practice.

The schema names, along with their reliability and descriptive statistics, are given in Table S1 in the Supplementary material. These statistics allow for further analysis, and reliability values are satisfactory – only Unrelenting standards and Entitlement schemas are below α<0.7. The results were elaborated using IBM SPSS v26 and AMOS v26. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to verify fitting the given models (four and five domains) to the data. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to check how schemas align to second-order factors.

In order to make the study complete, even though this is outside the main purpose of the study, supplementary validity assessment was performed with the Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg2015), PANAS-X (Watson and Clark, Reference Watson and Clark1999), positive orientation (Caprara et al., Reference Caprara, Alessandri, Eisenberg, Kupfer, Steca, Caprara, Yamaguchi, Fukuzawa and Abela2012) and the GHQ-28 (Goldberg and Williams, Reference Goldberg and Williams2000).

Results

The study’s aim was to compare the validity of the structure of 4 and 5 domains. For this purpose, exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory (CFA) analyses were carried out. Due to the testing of assumed models, the confirmatory analysis came first, and the exploratory analyses were performed later on and treated as supplementary.

The correlation matrix (see Table S2 in Supplementary material) shows that the schemas are related to each other, but they are clearly separate constructs – Pearson’s r values are between .224 and .722, which justifies further analyses.

Confirmatory factor analysis

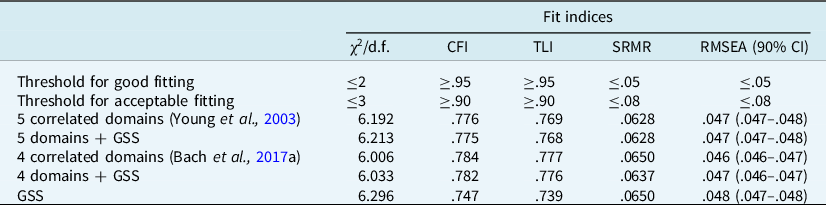

The analyses began with the testing of the assumed models using CFA. In the models, the indicators were individual items, schemas – first-order factors, domains – second-order factors. The identified models were: the model assuming five correlated domains (according to Young’s model; Young et al., Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2003) and five domains with one third-order factor (general schema severity – GSS), analogically a model assuming four correlated domains (Bach et al., Reference Bach, Lockwood and Young2017a,b) and four domains with one third-order factor: GSS, and a model with one second-order factor – general schema severity. These models exhibit a relatively poor fit to the data. The model of four correlated domains clearly comes the closest to meeting the assumptions (Table 1).

Table 1. Fit indices for the tested models

GSS, general schema severity; χ2/d.f., relative chi-square; CFI, comparative fit index; TLI, Tucker–Lewis index; RMSEA (90% CI), root mean square error of approximation (90% confidence interval); SRMR, standardized root mean squared residual.

However, as some researchers point out (Yuan, Reference Yuan2005), the distributions of fit indices can be affected by the sample size or distribution of data, so they do not necessarily indicate a poor fit. For this reason, fit indices (especially threshold points) should not be the only way to evaluate a model’s validity in confirmatory analysis. Equally important is the analysis of factor weights, which, together with fit indices, represents the quality of measurement of latent variables (McNeish et al., Reference McNeish, An and Hancock2018). Hancock and Mueller (Reference Hancock and Mueller2011) claim there can be observed some reliability paradox, whereby models with high factor loadings have a poorer fit to the data.

Therefore, the factor weights of the schemas forming domains were compared (Table 2). All of the schemas present high factor loadings (λ-s), mainly in the 4-domain model. Only Self-Sacrifice schema has a λ value is lower than 0.6.

Table 2. Factor loadings of the schemas forming domains and one general factor

D/R, disconnection/rejection; OV, over-vigilance; IA, impaired autonomy; IL, impaired limits; OD, other-directedness; ER, excessive responsibility.

There were also calculated factor loadings of each item forming the schema for the versions with four and five domains and one second-order factor.

In the relatively best-fitting and recommended model with four domains, most items are characterised by factor loadings above 0.6. Values within the range 0.5 to 0.4 only apply to a few items: number 90 (Punitiveness), 11, 29 (Self-Sacrifice), 2 (Abandonment), 31, 49 (Unrelenting standards), 32, 50, 68 and 86 (Entitlement). Lower loadings characterise exactly the same items (with the exception of number 90) in the 5-factor solution, and their indices are even lower (below 0.4). The Self-Sacrifice schema also imparts a low loading to the Other-Directedness domain in the 5-factor solution (0.423, cf. Table 2), similarly as in 4-factor model to the Excessive responsibility domain (0.576).

Exploratory factor analysis

As the CFA analysis did not provide unequivocal results allowing one to consider any model as clearly better, it was checked whether exploratory analyses would bring additional conclusions. The factor analysis from the IBM SPSS v26 package was used, in Varimax rotation with Kaiser normalisation. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (28013.676, d.f.=153, p<.001), and KMO Measure (=.950) confirmed the legitimacy of carrying out analyses in order to reduce dimensions. Three models were calculated: with the assumed number of 4 and 5 factors (according to the number of domains in the compared proposals) and with a released number of factors. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Factor loadings of the schemas in the tested solutions

The obtained results indicate that the 4-factor solution reflects the assumed structure much better. Two domains are accurately reproduced: Impaired Autonomy and Impaired Limits (only the Insufficient Self-Control schema has high loadings for two factors). The Disconnection and Excessive Responsibility domains have three schemas in total (respectively: Mistrust, Negativism and Self-Punitiveness), which place the factor loadings in a different domain, although in the case of Mistrust, the difference between the loadings is relatively small. In the case of a solution with five domains, the level of this compliance is definitely lower. In the best case, only ten schemas reflect the assumed structure (see Table 3). It is worth noting that in the absence of assumptions as to the number of factors, the analyses indicate a two-factor solution, which was also described as accurate by Bach and Young (Bach et al., Reference Bach, Lockwood and Young2017a).

Validity analysis

Validity analysis is not the main aim of the study; however, some supplementary information is provided to make the study complete.

Earlier analyses carried out during the cultural adaptation of the YSQ confirmed the external convergence and divergence validity as well as the reliability of the measurement over time (Oettingen et al., Reference Oettingen, Chodkiewicz, Mącik and Gruszczyńska2018). Supplementary Table S3 presents Pearson’s coefficient for schemas and some positive (Self-esteem, Positive affect, Positive orientation), and negative (Negative affect, somatic symptoms, anxiety, functioning disorders, and depression symptoms) characteristics. As it was supposed, in compliance with schema theory, most of the schemas’ intensities are positively correlated to aspects of psychopathology and negatively to positive characteristics. In most cases, obtained correlation coefficients are moderate (.30–.50), suggesting the YSQ-S3 is not redundant in other scales measuring characteristics of psychopathology or well-being. Self-Sacrifice, Entitlement and Approval seeking schemas have, however, lower indicators (>.20), similar to the study cited above. In turn, contrary to that study, somatic symptoms are significantly connected to schemas but with low correlations. The highest positive correlations are with depression symptoms and negative affect, and negative correlations with self-esteem and positive orientation. These findings support theoretical assumptions and indicate that the YSQ is a valid measure. However, it needs further research due to non-conclusive results in different studies.

Discussion

The aim of presented research was to verify which of the discussed schema models finds better confirmation in the data – the model of five domains applied hitherto or the structure of four factors revised in 2018. A large non-clinical sample with a wide age profile and almost equal gender structure was used for the analyses.

The results of the CFA analyses indicate that none of the tested models is well suited to the data; however, the model of four correlated domains is the closest to the thresholds. It is also characterised by higher factor loadings than in other tested models, which supports its acceptance. Similar conclusions were obtained by Aloi et al. (Reference Aloi, Rania, Caroleo, Carbone, Fazia, Calabrò and Segura-Garcia2020a,b). The models in their research did not achieve acceptable goodness of fit indices; however, the analysis of factor loadings allowed for considering the four-factor solution as more optimal. It is worth noting here that the authors mentioned above obtained weak, irrelevant factor loadings of individual items against the appropriate schemas. In our research, the loadings of both items and (above all) schemas in regard to domains were at least satisfactory.

Confirmatory analyses, as a rule, are conducted during the work on questionnaire adaptation. Cultural differences are, possibly, one of the reasons for the diverse and ambiguous effects, and certainly, they are associated with the different questionnaires used in the analyses (examining 15 or 18 schemas, in their full or short versions). Slovak studies indicated the structure of 18 schemas but did not confirm the validity of the second-order factors (Slepecky et al., Reference Slepecky, Kotianova, Sollár, Ociskova, Turzakova, Zatkova, Popelkova, Prasko, Solgajová, Romanova and Trizna2019). According to Bach et al. (Reference Bach, Lockwood and Young2017a,b), western societies are similar in the psychometric properties of the YSQ in terms of factorial findings (Calvete et al., Reference Calvete, Orue and González-Diez2013; Hawke and Provencher, Reference Hawke and Provencher2012; Kriston et al., Reference Kriston, Schäfer, Jacob, Härter and Hölzel2013; Saariaho et al., Reference Saariaho, Saariaho, Karila and Joukamaa2009). However, the French research did not confirm the assumed structure, and the confirmatory models were not fitted to the data acceptably (Bouvard et al., Reference Bouvard, Denis and Roulin2018). The structure of the four domains rarely appears in the studies. Nevertheless, some studies indicate it as a better alternative to the tested five-factor structure. Such results were obtained, for example, in a Thai study, in which the analyses confirmed the structure of 18 schemas as well as four higher-order factors (Sakulsriprasert et al., Reference Sakulsriprasert, Phukao, Kanjanawong and Meemon2016); moreover, similar results were obtained by Unoka et al. (Reference Unoka, Tölgyes and Czobor2007), Hoffart et al. (Reference Hoffart, Sexton, Hedley, Wang, Holthe, Haugum, Nordahl, Hovland and Holte2005) and Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Taylor and Dunn1999). Calvete et al. confirmed the structure of 18 schemas and two domains, suggesting that the other schemas seem to form the third, larger domain (Calvete et al., Reference Calvete, Estévez, López de Arroyabe and Ruiz2005).

The exploratory analyses fairly unambiguously support the four-factor model whose structure was recreated better than in the case of five domains. However, it should be emphasised that in both cases, there are schemas whose loadings have similar values in two factors; in particular, this refers to Defectiveness and Mistrust schemas. In turn, after applying the fully exploratory nature of analyses with the released number of factors, the two-factor solution turns out to be the most accurate. The schemas creating them partly coincide with those that achieved the highest factor loadings for the two-component proposal in Bach, Lockwood and Young’s proposal (Bach et al., Reference Bach, Lockwood and Young2017a). In the case of Internalisation – all of the five, and for the case of externalisation – three of them. An evident weakness of the obtained two-factor solution is that as many as five schemas have relatively high loadings in both factors, whereas only four schemas can be considered exclusively assigned to the second factor, and nine schemas to the first factor. This may lead to the conclusions, which are often verified in research on the factor structure, that only the structure of the first-order factors is valid while their organisation into domains is difficult to confirm (Calvete et al., Reference Calvete, Estévez, López de Arroyabe and Ruiz2005; Kriston et al., Reference Kriston, Schäfer, von Wolff, Härter and Hölzel2012). Perhaps it is also legitimate to consider the bifactor model, applied in some works (Kriston et al., Reference Kriston, Schäfer, von Wolff, Härter and Hölzel2012; Oettingen et al., Reference Oettingen, Chodkiewicz, Mącik and Gruszczyńska2018), as it assumes the existence of one common factor and specific factors. According to Kriston, this factor can be understood as a relatively constant feature influencing the development of psychopathology traits. In Kriston’s research, the common factor explained the greater proportion of variance in 11 schemas, to the greatest extent for the Dependence schema (Kriston et al., Reference Kriston, Schäfer, von Wolff, Härter and Hölzel2012), while in the study of Oettingen et al. the most saturated common factor was the Defectiveness schema (Oettingen et al., Reference Oettingen, Chodkiewicz, Mącik and Gruszczyńska2018).

Essentially, the above findings encourage conducting further analyses. From the point of view of psychotherapeutic practice, when the therapist works on specific schemas, the results of research to date allow a degree of peace of mind: almost all studies confirm the validity of the structure with 18 schemas and their good reflection in the data. A slightly bigger problem arises when researchers use domains in their analyses. Due to the varying fitting of this structure to empirical data, the obtained results may differ significantly. It appears that schemas, as a basic structure, are a good starting point for research. In the case of the necessity to use domains, however, the structure of four domains seems to be a better option, as it appears much more often in exploratory and confirmatory analyses (Hoffart et al., Reference Hoffart, Sexton, Hedley, Wang, Holthe, Haugum, Nordahl, Hovland and Holte2005) comparing with the five domains which were confirmed relatively rarely (Hawke and Provencher, Reference Hawke and Provencher2012).

Taking into account the variety of results obtained in the research mentioned above, it is worth mentioning the different view of problem of the schemas’ structure. Many studies to date point that some schemas, mainly from the Disconnection domain, are much more important for the development of psychopathology, while others are conditional (they appear in response to other schemas) (Young et al., Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2003). Similarly, the internal differentiation of the content of the same schema may be related to its belonging to different domains, depending on the dominance of a specific feature/symptom/belief. Currently, research and understanding of psychopathology are heading more in a dimensionally rather than a categorical character, as exemplified by the dimensional personality disorder model in the ICD-11 or the increasingly discussed HiTOP model (Forbes et al., 2021; HiTOP Clinical Network). The HiTOP describes a hierarchical model of psychopathology allowing – inter alia – paying attention to symptoms that are not distinctive, but referring to different disorders, or those that are not crucial for the diagnosis (Ruggero et al., Reference Ruggero, Kotov, Hopwood, First, Clark, Skodol, Mullins-Sweatt, Patrick, Bach and Cicero2019). Such direction for understanding the psychopathology might be useful and interesting also for schemas.

Limitations and conclusions

The presented study has some strengths, and the limitations need some further attention.

Undoubtedly, the advantage of this study is the large size of the group and the relatively homogeneous age and gender structure. All subjects were also people without any mental disorders. Young and Beck noted that negative beliefs about oneself are also present in the population of healthy people (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Butler, Brown, Dahlsgaard, Newman and Beck2001; Young et al., Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2003; Young et al., Reference Young, Rygh, Weinberger, Beck and Barlow2008). Also, some studies indicate that healthy people differ from the clinical group mainly in the severity of the schemas but not in their composition (Chodkiewicz and Gruszczyńska, Reference Chodkiewicz and Gruszczyńska2018). However, claiming that the structure of the four domains will reflect the data in the population of people from clinical groups in a better way does not appear justified. The lack of such a group, even less numerous, is a significant limitation for the study. Also, the excluding criteria may be interpreted as a limitation.

On the one hand, the study’s strength is that the results are not affected by strongly activated schemas. However, on the other hand, it may make the generalisation of the results worthy of more caution, as we do not know what happens to the domains’ structure if some schemas are more intense than others. The remaining limitations are more related to other factors, such as the choice of the questionnaire type (its short version), the way the research is conducted, the culture and language of translation (different cultures differ in the obtained results), or the way statistical analyses are compiled and the options are selected, which may or may not lead to different results (Kriston et al., Reference Kriston, Schäfer, von Wolff, Härter and Hölzel2012). This is probably one of the few studies focused on a direct comparison of two models of latent schema structure. Further research is needed, involving clinical samples, and allowing the comparison of the results obtained with different language versions and in different cultures. The similarity of the conclusions obtained by Aloi et al. (Reference Aloi, Rania, Caroleo, Carbone, Fazia, Calabrò and Segura-Garcia2020a,b) also justifies the use of the new model proposal (Bach et al., Reference Bach, Lockwood and Young2017a,b).

Despite the limitations mentioned above, the analyses lead to the general conclusion that the latest proposal for the structure of schemas, grouping them into the four higher-order domains, is better reflected in the data, and therefore, more acceptable than the previous one, assuming five domains. This conclusion may be useful both for researchers and (mainly) practicians – psychotherapists. It seems that schema domains in the 4-domain structure may be more coherent, and consequently – more interpretable. Working on domains, if they consist of weakly related schemas, may lead to lower effects, while when schemas create cohesive structure, they point to similar beliefs easier to change together.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This work was supported by The National Science Centre, Poland under grant number 2017/01/X/HS6/00232 and the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin under Disciplined Grant number 05-0511-2.

Conflicts of interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin Ethics Committee for Scientific Research (reference 2016.09.06). The research was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to the interview of each participants.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within its supplementary material.

Author contributions

Dorota Mącik: Conceptualization (lead), Funding acquisition (lead), Methodology (equal), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Radosław Mącik: Conceptualization (supporting), Formal analysis (lead), Methodology (equal), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (lead). Both authors contributed to the study conception and design. Concept of the study, data collection and the first draft of manuscript was performed by Dorota Mącik. Statistical analysis and was made by Radosław Mącik. Both authors read, revised, corrected, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465821000539

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.