1 Yod-coalescence and yod-dropping: the historical background

1.1 Introduction

As explained in Yañez-Bouza (Reference Yáñez-Bouza2020), when setting up ECEP, we decided to supplement Wells’ (Reference Wells1982) lexical sets, which relate to vowels, with five consonantal sets: deuce, feature, sure, heir and whale. These were chosen because earlier research on the phonology of eighteenth-century English (Beal Reference Beal and Britton1996, Reference Beal1999) had identified changes in progress at that time with regard to yod-coalescence of consonants in deuce, feature and sure, and the presence or absence of initial /h/ in heir and whale.Footnote 1 Eighteenth-century sources revealed diachronic and diatopic variation, along with evidence for stigmatisation of certain variants. However, Beal's (Reference Beal and Britton1996) research was focused on one of the sources included in ECEP (Spence Reference Spence1775), drawing comparisons from Burn (Reference Burn1786), Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780) and Walker (Reference Walker1791), leading her to conclude that a more comprehensive survey of eighteenth-century sources was a desideratum. Whilst not fully comprehensive of all the sources available, ECEP provides the opportunity to explore in greater breadth and depth the variability of eighteenth-century English pronunciation and the trajectory of sound changes in progress at the time. In this article, we focus on two related, perhaps complementary sound changes: the yod-coalescence of consonants preceding reflexes of Middle English /yː, iu, ɛu, eu/ and yod-dropping, that is, the elision of /j/ in sequences of /ju(ː)/ which developed from the Middle English vowels and diphthongs listed above. We also consider the state of affairs in the eighteenth century as a result of an earlier sound change, unstressed syllable vowel reduction of the reflex of Middle English /yː/ etc., which resulted in yod-less variants at the start of the period under investigation.Footnote 2

1.2 Development to 1700

According to Dobson (Reference Dobson1957: II.701–4, II.799–803), from at least 1500, the reflexes of Middle English /yː, iu, ɛu, eu/ had become indistinguishable from each other. The evidence from sixteenth-century sources examined by Dobson shows that the pronunciation of the resulting merged phoneme varied between [yː] and [iu]. In the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the [iu] variant became more common and changed to [juː]. Following from this, after certain consonants, mostly /s/ and /z/, but more rarely /t/ and /d/, the /j/ is coalesced with the preceding consonant so that /sjuː, zjuː, tjuː, djuː/ become /ʃuː, ʒuː ʧuː, ʤuː/ (Dobson Reference Dobson1957: II.957–60). Alternatively, the /j/ could be eliminated without coalescence with the preceding consonant, as in Present-day English sue, suit, suitable and (in some varieties, most notably American English) due, duke, Tuesday, tune (see also Minkova Reference Minkova2014: 141–5). Wells distinguishes ‘early yod-dropping’ (Reference Wells1982: 207) after palatals, after /r/ and after consonant + /l/, as in chew, rude and blue respectively; and ‘later yod-dropping’ (Reference Wells1982: 247) after all coronal consonants, as in tune, duke, new, enthusiasm, suit, resume, lewd. Where original /iu/ occurred in unstressed syllables, as in the feature set in ECEP, both yod-less forms (with reduction of unstressed /iu/ > /ə/ and no intermediate yod; see Dobson Reference Dobson1957: II.850–3) and yod-coalesced forms (preceded by /iu/ > /juː/) are likewise attested from the sixteenth century onwards; in the former type, the vowel may be reduced to /ə/, or the sequence /juːr/ to syllabic /r̩/.Footnote 3 Thus creature could be pronounced /kriːtjuːr, kriːʧuːr, kriːtər/ or /kriːtr̩/.

By the end of the seventeenth century, then, for a word such as tune, three variant pronunciations are attested: /tjuːn, ʧuːn, tuːn/. Where /t/ or /d/ precede earlier /juː/, these three variants still occur today: /tjuːn/ is the more careful and conservative variant in most varieties of British English; /ʧuːn/ the more common British variant; and /tuːn/ the usual pronunciation in American English and some British varieties such as some varieties of London English and, according to Hughes et al. (Reference Hughes, Trudgill and Watt2012: 69), ‘a large area of eastern England’ stretching from Suffolk to Nottinghamshire, where ‘/j/ has been lost before /uː/’ after all consonants. The sound changes under consideration in this article – yod-coalescence and yod-dropping/unstressed syllable yod-lessness – were well under way by the beginning of the eighteenth century and in some varieties of British English have not completed, since variability is still evident even in RP/Standard Southern English. In the next section, we will review the evidence from ECEP in order to address the following questions:

i. Is there a chronological pattern whereby yod-coalescence or yod-dropping become more or less frequently attested in later sources?

ii. Is there a diatopic pattern whereby authors from some parts of Britain show a greater or lesser extent of yod-coalescence/yod-dropping?

iii. Is there evidence that some of the variants attested are stigmatised?

iv. Can we determine phonological regularities in the distribution of variants? Do some environments favour or disfavour these sound changes? We will consider the effects of stress placement, of the nature of the preceding phoneme, and of the presence/absence of following /r/.

v. What role does word frequency play in the lexical distribution of these variants?

2 Data analysis: chronology, social and geographical factors

2.1 The ECEP data

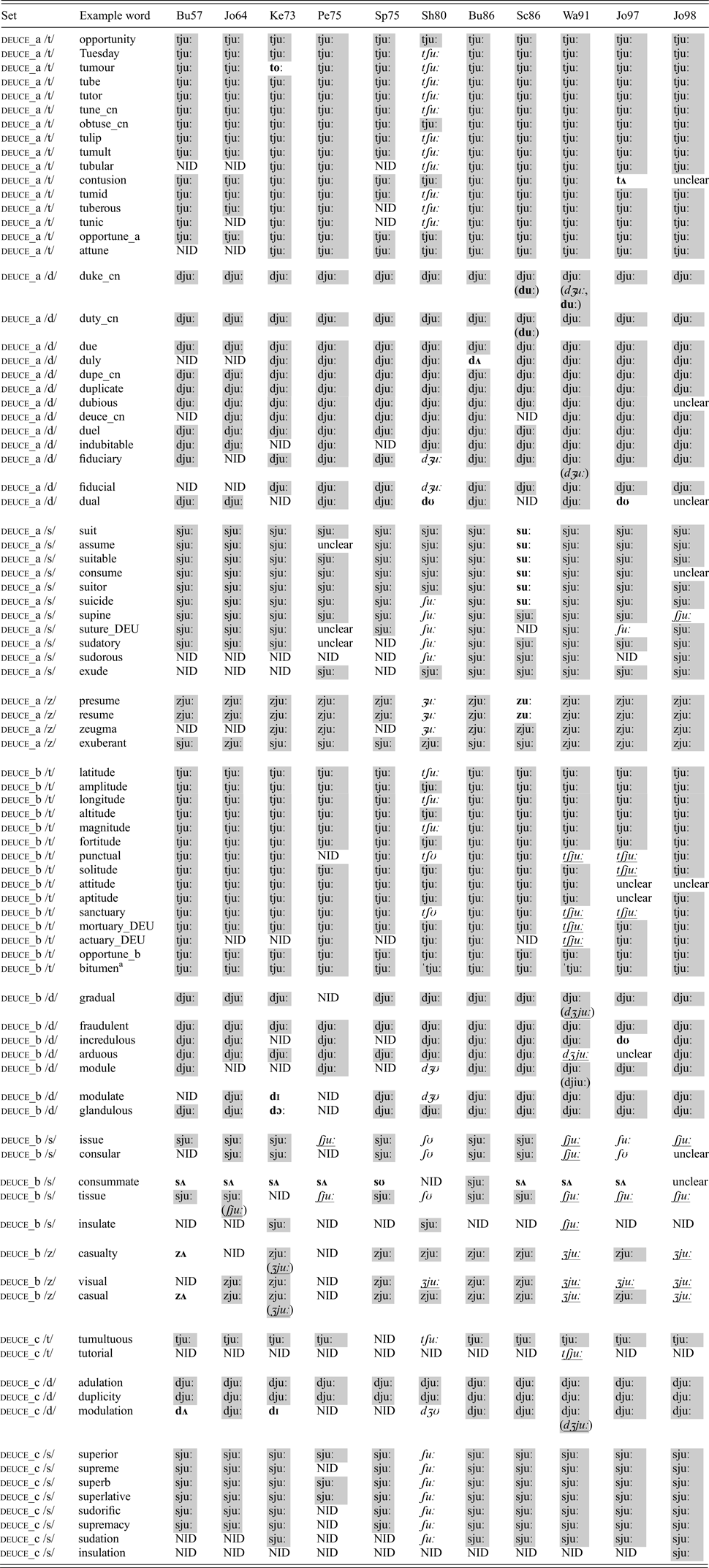

As explained in Yañez-Bouza (Reference Yáñez-Bouza2020), the phonological data in ECEP consist of transcriptions of the relevant segments of such examples given by Wells (Reference Wells1982) for his keywords as could be found in eleven eighteenth-century pronouncing dictionaries. Since Wells intended his keywords to facilitate comparison of English accents on the basis of their vowel phonology, we supplemented these keywords with five consonantal sets, two of which, deuce and sure, were designed to provide evidence for yod-coalescence of /t d/ and /s z/ before /juː/ respectively, where the /uː/ has not reduced to schwa in Present-day English, whilst feature contains words in which /uː/ has reduced to schwa. The three data sets are set out in Appendix tables A1 and A2. Table A1 shows data for the deuce set, in which there is no /r/ following the vowel. This set is divided into three subsets: deuce_a where the vowel is in a stressed syllable, as in assume; deuce_b where it is unstressed in the syllable following the stressed one, as in issue; and deuce_c where it is unstressed in the syllable preceding the stressed one, as in modulation. Table A2 presents data for the sure and feature sets, in which /r/ follows the vowel. sure_a includes words in which the vowel is in a stressed syllable, as in sure. The sure_b, sure_c and feature sets all have the vowel in unstressed syllables.Footnote 4 These three sets differ in that those in the feature set, such as nature, have schwa in Present-day English according to the OED, whereas those in sure_b as in century and sure_c as in duress have at least a main variant with /uː/. Sources are set out in order of date of publication, but it is worth bearing in mind that the authors’ life dates at the time of publication vary: Spence (1750–1814) was only twenty-five years old when his dictionary was published in 1775, but Sheridan, whose General Dictionary was published in 1780, was ‘probably born in early 1719’ according to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Thomson Reference Thomson2004). So, although the dates of publication are only five years apart, Sheridan's dictionary is the work of a man who acquired English in the early eighteenth century, whilst Spence's reflects the language of the mid century. In the following subsections, we will discuss the chronology of yod-coalescence and yod-dropping according to the dates of publication, but will also bear in mind the authors’ life dates.

2.2 Chronological patterns

In the Appendix, tables A1 and A2, words showing evidence for yod-coalescence in the dictionaries concerned are highlighted either in italics where the evidence is for a consonant undergoing yod-coalescence followed by /uː/, or in italics and underlining where the modified consonant is followed by /juː/. Both sets of evidence point to yod-coalescence and so can be considered together. It is likely that authors giving transcriptions indicating /juː/ after a coalesced post-alveolar consonant were influenced by their tendency to describe the ‘long’ sound of orthographic <u > as /juː/, which is consistent with the name of the letter in the English alphabet, although this practice does not preclude some of them actually recommending pronunciations with both a modified consonant and yod. Words showing evidence for yod-dropping or yod-lessness are highlighted in bold, whilst those showing neither yod-dropping nor yod-coalescence are highlighted in grey.

At first glance, there seems to be no straightforward chronological trajectory for yod-coalescence. For the deuce_a set (e.g. dúke), there is no evidence of yod-coalescence in sources published earlier than 1780 (Sheridan), but there is likewise very little evidence of yod-coalescence in sources published later than 1780. For deuce_b, there is some evidence of yod-coalescence in Perry (Reference Perry1775), e.g. íssue, and more instances of yod-coalescence in sources later than 1780, e.g. púnctual and vísual in Walker (Reference Walker1791) and Jones (Reference Jones1797), but Sheridan still shows more yod-coalescence than any other source. For the sure and feature sets, there is a clearer pattern of increasing yod-coalescence in some contexts as the century proceeds. For the word sure itself and its derivatives, all sources from 1773 onwards with the exception of Scott (Reference Scott1786) have yod-coalescence in the majority of cases, whilst for the sure_b and feature sets (e.g. compósure, pléasure) Perry and Spence (both 1775) have a few instances of yod-coalescence, Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780) has yod-coalescence in most cases, and all later sources except Scott (Reference Scott1786) likewise have yod-coalescence for most words in these sets. So, in some environments (section 3 below), there is a tendency for yod-coalescence to increase through the last quarter of the eighteenth century, but Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780) with his relatively high level of yod-coalescence and Scott (Reference Scott1786) with his total absence of yod-coalescence stand apart. Between the two editions of Jones (Reference Jones1797, Reference Jones1798), there is a slight decrease in yod-coalescence, which, as we argue in section 2.3, is possibly due to the stigmatisation of variants involving yod-coalescence at this time.

Regarding the yod-less forms resulting from the reduction of original /iu/ to /ə/ in unstressed syllables (see section 1.2, with further discussion in sections 3.1 and 3.3), a clear pattern emerges for the sure_b and feature sets. There are some yod-less forms in Buchanan (Reference Buchanan1757); Johnston (Reference Johnston1764), Kenrick (Reference Kenrick1773) and Perry (Reference Perry1775) have a majority of words in these sets without yod; and sources later than 1775 have no yod-lessness, except for isolated examples such as century and suture in Burn (Reference Burn1786), and a yod-less variant for nature in Walker (Reference Walker1791). Spence (Reference Spence1775) seems anomalous here, with yod-lessness only in century and censure. This chronological pattern indicates a restitution of yod in these unstressed syllables part way through the century, possibly influenced by dialects which had developed /juː/ rather than reduced /ə/ from original /iuː/ in this environment, as likely to be evidenced by Spence (Reference Spence1775), Burn (Reference Burn1786) and Scott (Reference Scott1786); these yod-restored forms often then underwent coalescence. In the deuce_b set, most sources show little yod-lessness, except for the word consummate (adj. and vb.) which has /s/ followed by an unstressed vowel in all sources.

As far as stressed-syllable yod-dropping is concerned (see section 3.1), Kenrick (Reference Kenrick1773) provides the earliest isolated occurrence (tumour), followed by a single instance (dual) in Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780), but Scott (Reference Scott1786) provides the majority of examples, notably for most words in the deuce_a set for which /s/ or /z/ preceded the vowel (suit, assume, suitable, consume, suitor, suicide, presume, resume). Yod-dropping after /d/ or /t/ is very sporadic: Kenrick has it in tumour, Sheridan and Jones (Reference Jones1797) in dual, Jones (Reference Jones1797) also in contusion. Whilst both Walker (Reference Walker1791) and Scott (Reference Scott1786) give /djuːk/ as their primary pronunciation for duke, both provide evidence for an alternative with yod-dropping. Scott simply provides the two pronunciations, as he also does for duty, but Walker has the following comment under duke:

There is a slight deviation often heard in the pronunciation of this word, as if written Dook; but this borders on vulgarity; the true sound of the u must be carefully pronounced, as if written Dewk. (Reference Walker1791: s.v. duke)

Walker is not alone in condemning yod-dropping: Elphinston, who refers to yod as ‘liquefaction’, comments as follows:

The vulgar English drop it [/j/], not only in the provinces: in the capital do we hear Look, bloo, rool, trooth, noo, toon, doo, dook, soo; for Luke, blue, rule, truth, new, tune, due and dew, duke, sue; and the like. (Reference Elphinston1786–7: II.10)Footnote 5

This suggests that, whilst the earlier unstressed yod-less forms in the sure_b and feature sets declined by the later eighteenth century, yod-dropping in the stressed deuce_a set was increasing, but the innovation was considered ‘vulgar’ and therefore not recommended by the pronouncing dictionaries which provide the data for ECEP. In the next subsection, we will look more closely at the evidence for stigmatisation of yod-coalescence and consider whether this can explain the apparent lack of a clear chronological pattern discussed above.

2.3 Stigmatisation

The eighteenth century was a period in which the codification of English became the prime concern of grammarians, lexicographers and, in the second half of the century, authors of elocution guides and pronouncing dictionaries. All the data in ECEP are taken from pronouncing dictionaries, which were intended as guides to acceptable pronunciation. As such, they reflect developments in what was considered prestigious pronunciation, but some authors, most notably Walker, also provide comments on pronunciations which are unacceptable, the most frequent epithet for these being vulgar (Trapateau Reference Trapateau2016). Such comments have been included in ECEP when they refer to variant pronunciations of the example words listed.

We saw in the previous section that the decline in early yod-less forms, and the very sporadic nature of transcriptions showing later yod-dropping, was accompanied by negative comments about pronunciations without yod. With regard to yod-coalescence, a strictly chronological survey of the ECEP sources revealed a pattern whereby this was less common in the earlier sources, reached a peak with Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780), but then declined again in later sources. We need to consider whether social factors can shed any light on this undulating pattern.

We saw in section 1.2 that evidence for yod-coalescence before /juː/ exists from the seventeenth century onwards, particularly with regard to yod-coalescence of /s/ and /z/. Most seventeenth-century sources make no negative comments about this, but Christopher Cooper (Reference Cooper1687) includes a list of variants to be avoided by those who wish to ‘avoid a Barbarous Pronunciation … (sh) for (s) before (u) as Shure, Shugar, &c.’ (Reference Cooper1687, ed. Sundby 1953: 77–8). Cooper's remarks on ‘Barbarous Pronunciation’, coming as they do towards the end of the seventeenth century, may be seen as harbingers of the more normative/prescriptive attitudes of the eighteenth century. We saw in section 2.2 that yod-coalescence in words like sure and azure where earlier /s/ or /z/ precede the vowel is attested from Kenrick (Reference Kenrick1773) onwards in the ECEP sources, but that yod-coalescence of /t/ and /d/ is much more sporadic. Cooper makes no mention of the latter yod-coalescences, and seventeenth-century evidence for them is rare, so it would appear that yod-coalescence began with /s/ and /z/, was stigmatised from the late seventeenth century, became accepted in the course of the eighteenth century, and then moved on to /t/ and /d/, which in turn are stigmatised. Evidence for this stigmatisation can be found in several of the ECEP sources. Kenrick, whose 1773 dictionary is the earliest source in ECEP to show yod-coalescence in the sure and feature sets, rationalises the yod-coalescence of /t/ and /d/ before <i> and <e>Footnote 6 in words such as question, christian, bounteous, courteous by arguing that, in these cases, the vowel has the sound of ‘Y consonant’ and that ‘[i]n these cases … it is generally said that the ti and te have the force of ch’ (Reference Kenrick1773: 32). However, Kenrick goes on to comment that

a very general custom prevails, even among the politest speakers, of giving the t alone the force of ch in many words, such as nature, creature, &c. which are pronounced nachure, creachure, and that too euphoniæ gratia. (Reference Kenrick1773: 32)

Kenrick goes on to write that he ‘cannot discover the euphony’ in this pronunciation and to complain about yod-coalescence before <u>:

But why the t, when followed by neither i nor e, is to take the form of ch, I cannot conceive: it is my opinion, a species of affectation that should be discountenanced; unless we are to impute it to the tendency in the metropolitan pronunciation of prefacing the sound of u with a y consonant; or, which is the same thing, converting the t or s preceding into ch or zh, as in nature, measure, &c. (Reference Kenrick1773: 32)

In his own transcriptions, Kenrick has a yod-less form for nature, but yod-coalescence for measure. In these notes, he is trying to develop a rationale for when and why yod-coalescence should occur. He uses the terms ‘affectation’, ‘the politest speakers’ and ‘metropolitan’ rather than the more condemnatory ‘vulgar’, indicating that these pronunciations are used by people of a high social class in London, so he is not stigmatising them strongly. Indeed, he ends the above-cited observation by stating that ‘[t]hese are niceties, however, that foreigners and provincials need not give themselves much trouble about, though professors of English and public pleaders ought to get them ascertained’ (Reference Kenrick1773: 32–3).

We saw in section 2.2 that Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780) was the author who had the highest proportion of variants with yod-coalescence for the words listed in ECEP. We also noted that Sheridan, born around 1719, was older at the time of publication than the authors of other dictionaries published near to that date, so we might expect his pronunciations to be relatively old-fashioned. Indeed Walker (Reference Walker1791), who often takes issue with Sheridan's pronunciations, sometimes does so on these grounds. For example, in discussing variant pronunciations of the word merchant, Walker writes:

Mr. Sheridan pronounces the e in the first syllable of this word, like the a in march; and it is certain that, about thirty years ago, this was the general pronunciation; but since that time the sound of the a has been gradually wearing away; and the sound of e so fully established,Footnote 7 that the former is now become gross and vulgar, and is only to be heard among the lower orders of the people. (Reference Walker1791: s.v. merchant)

In this case, Walker considers Sheridan's transcription old-fashioned rather than incorrect, in that he acknowledges that the march pronunciation was formerly acceptable, but elsewhere Walker and others are highly critical of Sheridan. Where yod-coalescence is concerned, Walker sets out rules for where this should and should not occur. When discussing the pronunciation of <t>, Walker writes:

If we attend to the formation of t, we shall find that it is a stoppage of the breath by the application of the upper part of the tongue near the end, to the correspondent part of the palate; and that if we just detach the tongue from the palate, sufficiently to let the breath pass, a hiss is produced which forms the letter s. Now the vowel that occasions this transition of t to s is the squeezed sound of e, as heard in y consonant: which squeezed sound is a species of hiss; and this hiss, from the absence of accent, easily slides into the s, and the s into sh. Thus mechanically is generated that hissing termination tion, which forms but one syllable, as if written shun. (Reference Walker1791: 55)

Walker goes on to extend this explanation to words in which ‘the diphthongal vowel u’ [/juː/] appears in an unaccented syllable after <t > and notes that this ‘may be observed in the pronunciation of nature, and borders so closely on natshur, that it is no wonder Mr. Sheridan adopted this latter mode of spelling the word to express its sound’ (Reference Walker1791: 55).

Walker is here setting out a rule to explain the acceptability of yod-coalescence in unstressed syllables, which accords with the increased frequency of yod-coalescence in the feature set from 1775 onwards. In this case, he agrees with Sheridan's transcription. However, when it comes to words in the deuce_a set, where the syllable concerned is stressed, Walker is highly critical of Sheridan's pronunciations with yod-coalescence.

But Mr. Sheridan's greatest fault seems to lie in not attending to the nature and influence of the accent; and because nature, creature, feature, fortune, misfortune, &c. have the t pronounced like sh or tsh, as if written creat-chure, feat-tshure, &c. he has extended this change of t into tch, or tsh, to the word tune, and its compounds, tutor, tutoress, tutorage, tutelage, tutelar, tutelary, &c. tumult, tumour, &c. which he spells tshoon, tshoon-eble, &c. tshoo-tur, tshoo-triss, tshoo-tur-idzh, tshoo-tel-idzh, tshoo-tel-er, tshoo-tel-er-y, &c. tshoo-mult, tshoo-mur, &c. … as they are often pronounced by vulgar speakers. (Reference Walker1791: 55)

Walker applies the same rule regarding accented and unaccented syllables to the yod-coalescence of /d/, /s/ and /z/. Indeed, he asserts that it is a general rule that coalescent changes like this are more acceptable in unstressed syllables. Thus he states that verdure is pronounced ver-jure, but ‘Duke and reduce, pronounced juke and re-juce, where the accent is after the d, cannot be too much reprobated’ (Reference Walker1791: 43). Where <s > is concerned, Walker explains his rules about accented and unaccented syllables at length, then goes on as follows:

This analogy leads us immediately to discover the irregularity of sure, sugar, and their compounds, which are pronounced shure and shugar, though the accent is on the first syllable, and ought to preserve the s without aspiration [i.e orthographic <h > ]; and a want of attending to this analogy has betrayed Mr. Sheridan into a series of mistakes in the sound of s in the words suicide, presume, resume, &c. as if written shoo-icide, pre-zhoom, re-zhoom, &c. but if this is the true pronunciation of these words, it may be asked why is not suit, suitable, pursue, &c. to be pronounced shoot, shoot-able, pur-shoo, &c. (Reference Walker1791: 54)

Walker is thus highly critical of Sheridan's tendency to have yod-coalesced consonants before /juː/, but in this case, unlike that of merchant, the criticism is not that Sheridan is old-fashioned, but that he does not pay enough attention to ‘analogy’ and that his pronunciations are those of ‘vulgar’ speakers.

Walker is not alone in his criticism of Sheridan. Although Sheridan had a very successful career as an elocutionist, he was later overshadowed by Walker, whose rule-based approach appealed to the late eighteenth-century readership. Walker's criticism of Sheridan may have been informed by an anonymous publication entitled A Caution to Gentlemen who Use Sheridan's Dictionary (1790), which sets out the ‘errors’ perpetrated by Sheridan. The ‘first general error’ is Sheridan's spelling of nature, torture, tortuous and saturate as na-tshur, tart-tshur, tart-tsho-us and sat-tsho-rate. The author states ‘that no one but an IRISHMAN could imagine the sound of -TU- is properly represented by the Gothic combination -TSHO’ (1790: 6), and that ‘if he be ambitious of passing for an English gentleman, let him avoid, with the utmost care, Mr. Sheridan's -SH-’ (1790: 7). Sheridan was ‘an Irishman’ and was often criticised on these grounds, but, as we shall see in the next section, there is no evidence that yod-coalescence was or is an Irishism.Footnote 8

This overt criticism of Sheridan's yod-coalesced pronunciations could perhaps go some way towards explaining the reduction in tokens with yod-coalescence between the second and third editions of Jones’ dictionary (Jones Reference Jones1797, Reference Jones1798). The full title of this dictionary is Sheridan Improved. A General Pronouncing and Explanatory Dictionary of the English Language: For the Use of Schools, Foreigners learning English &c. In which it has been attempted to improve on the Plan of Mr Sheridan, By correcting the Improprieties and avoiding the Discordancies of that celebrated Orthoëpist (Reference Jones1797: title page). We decided to use both the second and third editions of Jones’ dictionary as sources for ECEP because of the extent of changes made in the latter (the first edition is not available). It is evident from tables A1 and A2 in the Appendix that Jones changes several of the transcriptions showing yod-coalescence in the second edition to those retaining yod in the third edition. The words concerned are: suture (/ʃu:/ > /sju:/), punctual, solitude, sanctuary, assurance, procedure and ordure. Jones also introduces yod-coalescence to some words in the third edition: supine, ensure, maturation, mensuration, casualty and casual. Although these changes might at first appear haphazard, the following generalisations can be made:

• /t/ in post-stressed syllables only undergoes yod-coalescence before final /r/ in the third edition, thus punctual and century retain yod;

• /t/ in pre-stressed syllables undergoes yod-coalescence, as in maturation;

• /d/ does not undergo yod-coalescence in the third edition, even in unstressed syllables, as in procedure (the sole exception being verdure);

• /z/ undergoes yod-coalescence in unstressed syllables, as in casual;

• /s/ in unstressed syllables consistently undergoes yod-coalescence, as in mensuration;

• /s/ in stressed syllables undergoes yod-coalescence before syllable-final /r/, e.g. ensure, but not before syllable-onset /r/, e.g. assurance.Footnote 9

Although the numbers involved are small,Footnote 10 Jones in his third edition seems to be distancing himself further from Sheridan's tendency towards yod-coalescence and adopting Walker's rule-based approach. Strikingly, whereas the second edition permits variation between coalesced and non-coalesced forms within a given category of stress, phoneme type and rhoticity (e.g. deuce_b latitude with /tjuː/, but solitude with /ʧjuː/; casual with /zjuː/, but visual with /ʒjuː/), the third edition almost entirely eradicates such inconsistency in favour of following the list of ‘rules’ above (resulting in yod-retention in solitude, but coalescence in casual). The only change between Jones’ second and third editions which defies generalisation is the introduction of yod-coalescence in supine. In the third edition, Jones also expands his criticism of Sheridan's yod-coalescence. In the citation below, the part included in the earlier edition Jones (Reference Jones1797: viii) and highlighted in bold here is augmented as follows:

in examples like the following, it is strongly to be presumed that [Sheridan] is erroneous upon principle, and his misconceptions are therefore the more carefully to be avoided. The word convey is marked by Mr. Sheridan . . . as if pronounced convee; . . . lawsuit, lawshoot; latitude, latitshude; covetous, covetshus; mediocrity, mejocrity; vitiate, vishate; zodiak, zojak; satiety, sasiety; pertusion, pertshoosion; tune, tshoon, &c. &c.; and this system has corrupted the pronunciation of one of the most favourite comedians of the present day, who, I observe, whenever the word tutor occurs in his part invariably pronounces it tshootor. With equal propriety might Mr. S. have marked duel to be pronounced djooel, or jewel. (Reference Jones1798: iv)

Jones also adds to the front matter of the third edition a citation from Walker (Reference Walker1791) in which Sheridan is strongly criticised for ‘numerous instances of impropriety, inconsistency, and want of acquaintance with the analogies of the language’ (Jones Reference Jones1798). What we see here, then, is Jones distancing himself further from Sheridan and aligning himself closer to Walker, and the latter's rule-based approach which favours consistency and analogy. In his use of yod-coalescence, Sheridan is reflecting a trend in this direction, facilitated by the demise of unstressed yod-less forms, which, in turn, frees up more candidates for yod-coalescence (see section 3.3). Walker suggests that Sheridan's transcriptions reflect the pronunciation of the ‘vulgar’, so what we see in the apparent change in direction between Sheridan and the later sources in ECEP is the effect of prescriptivism and stigmatisation. This is not to say that Walker's pronunciations are artificial: he accepts that /s/ undergoes yod-coalescence in stressed syllables in the cases of sure and sugar,Footnote 11 for instance, and, as noted by Beal (Reference Beal, Dossena and Jones2003), Walker describes usage, but it is the usage of a particular class of speaker, a kind of ‘proto-RP’, making him both prescriptive and descriptive. As with sure and sugar, his pronunciations are often those which prevail in RP/Standard Southern English. We will consider the charge that Sheridan's tendency towards yod-coalescence was due to his being an Irishman in the next section, where we discuss the geographical distribution of yod-coalescence and yod-dropping.

2.4 Geographical distribution

Although all the authors represented in ECEP present accounts of what they considered to be correct pronunciation, given that no uniform RP-like sociolect existed at this point,Footnote 12 there are likely to be differences between the various accounts which may be attributed to the authors’ geographical origins (see Beal Reference Beal and Britton1996, Reference Beal1999). We know that Sheridan was Irish; Buchanan, Burn, Perry and Scott were probably Scottish; Spence was born in Newcastle upon Tyne in the northeast of England; and all the other authors were from the southeast of England. Walker and Jones were Londoners, Kenrick was born in Hertfordshire, and Johnston is referred to by Michael (Reference Michael1970: 568) as being ‘of Tunbridge Wells’ (Kent).

We have already discussed at length in the previous section Sheridan's position as the author with the greatest number of instances of yod-coalescence and the extent to which he was criticised for this by the Londoners Walker and Jones, and in the anonymous A Caution to Gentlemen who Use Sheridan's Dictionary. The latter in particular attributes Sheridan's propensity for yod-coalescence to his Irishness, but is there any evidence to support this? Hickey (Reference Hickey and Hickey2012) provides a list of ‘Irish’ features recurring in nineteenth-century literary representations of Irish English, but yod-coalescence before /ju:/ is not included in this list. Of course, literary dialect tends to represent features that are strongly indexed as occurring in the dialects concerned – stereotypes – so the absence of yod-coalescence from this list does not prove that the feature did not exist in Irish English in the eighteenth century, only that there was no widespread awareness of it as an Irish feature. There was certainly a tendency amongst Sheridan's critics to attribute any perceived fault in his dictionary to his Irish origins. Boswell relates how Dr Johnson, on hearing that Sheridan was intending to write his pronouncing dictionary, said ‘what entitles Sheridan to fix the pronunciation of English? He has in the first instance the disadvantage of being an Irishman’ (ed. Birkbeck Hill 1934: II.161). Sheridan himself was sufficiently aware of the differences between Irish English and ‘polite’ London English to include in his dictionary a set of ‘Rules to be observed by the natives of Ireland in order to attain a just pronunciation of English’ (Reference Sheridan1780: 59). Yod-coalescence, of course, is not included here, but neither is it in Walker's similar list, largely taken wholesale from Sheridan but with some additions (Reference Walker1791: ix–xi). The attribution of Irish origin to Sheridan's yod-coalescence could possibly be due to the critics’ overgeneralising of the context-free /s/ > / ʃ/ used by Shakespeare to characterise the speech of the Irish character MacMorris in Henry V (‘What ish my nation?’). The author of A Caution may have this in mind when warning the reader to avoid ‘Mr Sheridan's -SH- which “by my SHOUL have nothing at all to do” with syllables containing -TU-’ (1790: 7). However, this palatalisation of /s/ in Irish English is not connected to yod-coalescence. Since Sheridan is the only Irish-born author included in ECEP, we cannot conclusively state that his propensity to yod-coalescence was a feature of Irish English, but neither can we rule this out.

The clearest geographical pattern to emerge from the data in Appendix tables A1 and A2 is the absence or near-absence of yod-coalescence in Scottish sources. Buchanan (Reference Buchanan1757), Burn (Reference Burn1786) and Scott (Reference Scott1786) have no yod-coalescence, whilst Perry (Reference Perry1775) only has yod-coalescence of /s/ in unstressed syllables (issue, tissue) and of /s/ and /z/ before /r/. Spence (Reference Spence1775), born in Newcastle of Scottish parents, has a similar pattern to Perry. Wells notes that yod-coalescence is still less common in Scottish accents than in most other accents of English (Reference Wells1982: II.412), so the geographical pattern revealed in the ECEP data could well be a precursor of this.

3 Data analysis: phonology

3.1 Stress

Stress plays a critical role in the phenomenon: yod-coalescence is generally resisted in stressed syllables (deuce_a, sure_a) and is most commonly found in post-stress syllables (i.e. the unstressed syllable following the stressed syllable; deuce_b, sure_b, feature). This pattern underlies the rule-based approach adopted by Walker (Reference Walker1791; ‘analogy’ in his terminology), whose practice reveals the formulations below, implied less explicitly by his discursive ‘principles’ (see section 2.3 for quotations):

• No yod-coalescence in stressed syllables, as in tune, duke, endure, mature; the only permitted exceptions due to ‘custom’ are sure, sugar, and derived words, e.g. assure, insure, assurance (Walker Reference Walker1791: 43, 54–5; principles 376, 454–5, 462);

• /s z/ undergo yod-coalescence in post-stress syllables, as in censure, composure, pressure, pleasure (Reference Walker1791: 53–4; principles 450, 452);

• /t d/ undergo yod-coalescence in post-stress syllables before vowel hiatus (deuce_b; see section 3.2) or /r/ (sure_b, feature), as in punctual, sanctuary, mortuary, actuary, arduous, and century, verdure, nature, procedure (Reference Walker1791: 43, 55; principles 376, 461, 462–3).

The stressed-syllable exception in sure and its derivatives may reveal an interaction with the presence or absence of following /r/ (see section 3.3). The conducive post-stress environment shows an interaction with the quality of the yod-coalescing phoneme (see section 3.2), and is also the most common context for reduced yod-less forms in the earlier sources (see section 2.2; century in Burn (Reference Burn1786) is the latest), occurring after all phonemes in unstressed syllables before /r/, e.g. century, verdure, seizure, creature, procedure, treasure. As we know (Dobson Reference Dobson1957: II.850–3), this phenomenon must be considered separately from yod-dropping after any phoneme in a stressed syllable, which occurred later in the century, and our analysis according to stress and chronology (see section 2.2) is consistent with this acknowledged distinction. Unstressed yod-less forms and stressed yod-dropping also differ in their word frequency patterns (see section 4).

In pre-stress syllables (an unstressed syllable before the stressed syllable), yod-coalescence is arguably resisted more than in post-stress syllables, although there is not a large amount of data. There is again an interaction with phoneme-quality (see section 3.2), but the most interesting pattern that emerges is the stress-sensitive yod-coalescence alternation in morphologically related pairs in Walker (Reference Walker1791) and Jones’ third edition (Reference Jones1798): stressed [tj]útor, but pre-stress [ʧj]utórial in Walker; ma[tj]úre but ma[ʧj]urátion in Walker and Jones. Similarly, we see post-stress mó[dj(i)]ule but the pre-stress variant mo[ʤj]ulátion in Walker. This pattern is in keeping with the typology of lenition processes, of which affrication is a type, whereby lenition is inhibited in the stronger stressed-syllable-initial position, but permitted to occur in the weaker unstressed-syllable-initial position (see Honeybone Reference Honeybone, Nevalainen and Traugott2012 for such a formulation).

3.2 Phoneme type

Another phonological influence on yod-coalescence is, as has been noted throughout, the quality of the consonant involved. The different phonemes /t d s z/ behave differently in the different stress contexts: in stressed syllables, post-stress and pre-stress. This section will focus on the deuce set, and the similar patterns in pre-rhotic contexts (sure and feature) will be considered in section 3.3.

In stressed syllables (deuce_a) and pre-stress syllables (deuce_c), /d/ shows the least yod-coalescence, found only in the forms fiduciary/fiducial, as a variant pronunciation of duke in Walker, and in modulation in Sheridan (discussed below). /t/ has yod-coalescence only in Sheridan (aside from tutorial in Walker, discussed in section 3.1), and then only word-initially, producing alternations like yod-coalesced tune ~ uncoalesced attune. /s/ also has yod-coalescence word-initially only and again almost exclusively in Sheridan, e.g. [ʃ]úicide, [ʃ]upérior, but a[sj]úme, but not in words beginning suit- (suit, suitable, suitor) which are the most frequent /s/-initial forms in deuce_a (see section 4). Finally, /z/ undergoes yod-coalescence in all positions, not only word-initially, but still only in Sheridan, e.g. pre[ʒ]ume, [ʒ]eugma. Yod-coalescence fails in Sheridan's exuberant, and exude with /s/, probably because they were analysed as prefix ex- + stem-initial /juː/ (cf. Walker Reference Walker1791: 54, principle 454, where <x > is described as accented in éxercise and unaccented in exért, suggesting purported syllabifications with initial ex-).

In post-stress syllables (deuce_b), yod-coalescence is more common in /s z/ than in /t d/ (just as in sure and feature). There is near-regular yod-coalescence in these fricatives (though not many example words) in Perry, Sheridan, Walker and Jones (Reference Jones1798), e.g. issue, tissue, visual. Casual(ty) in Sheridan is the exception, although Kenrick, who reports no yod-coalescence anywhere else, has yod-coalesced variants for these two words.

As introduced in section 3.1, in /t d/, vowel hiatus following the /Cjuː/ sequence appears to promote yod-coalescence in Sheridan, Walker and Jones (Reference Jones1797), e.g. punctual, sanctuary, arduous (Walker), gradual (Walker variant), but uncoalesced amplitude, altitude, fortitude, fraudulent in all three. Hiatus might promote yod-coalescence if we posit the presence of a phonetic glide [w] to resolve hiatus (i.e. punctu[w]al), which in turn triggers a glide dissimilation Cj…w > Cyod-coalesced…w. Supporting this interpretation is the observation that sewer tends to be pronounced as ‘shore’ in the dictionaries which show a hiatus effect, with yod-coalescence before further loss of the /w/.

Unusually, Sheridan has yod-coalescence in module, modulate and modulation (in deuce_c); these are also the only words showing earlier yod-less forms after /d/ (Buchanan, Kenrick),Footnote 13 whose avoidance may underlie Walker's variant pronunciation for module with an emphasised yod element /djiuː/. The avoidance of a yod-less form may have been due to the desire to maintain a difference with model, a function Sheridan's yod-coalesced pronunciation also performs.

To summarise, the fricatives /s z/ were more prone to yod-coalescence than the plosives /t d/ in all stress contexts. Both were more likely to undergo yod-coalescence in word-initial position, and following hiatus was conducive to yod-coalescence in the plosives. All these patterns might have a basis in articulation and speech planning, as seen above for the hiatus context. For example, in /s z/ the high tongue position of palatal /j/ shapes frication noise to yield post-alveolar percepts, which may result in their being perceived and reinterpreted as post-alveloar fricatives. Whereas this would be the whole story in fricatives /s z/, in the alveolar plosives /t d/, reinterpretation would have to be from both alveolar to post-alveolar (through retracted place percepts due to coarticulation with the following /j/) and plosive to affricate (due to the greater frication noise on release into a high, front constriction; Ohala Reference Ohala and MacNeilage1983). Although it is likely that this reinterpretation in both manner and place occurred in a single step (e.g. listeners perceived a post-alveolar affricate rather than an alveolar plosive + /j/), it is possible that the added complexity in listener-based reinterpretation in /t d/ underlies its lagging behind the fricatives /s z/ in diachronic yod-coalescence.Footnote 14

3.3 Rhoticity

As previously stated (fn. 4), all the sources examined in this study are consistently rhotic, recommending the pronunciation of syllable-final /r/. The presence of /r/ after the context /Cjuː/ may have facilitated yod-coalescence, but it is difficult to tease apart this influence from the factors of stress and phoneme type which played an unambiguous role.Footnote 15 Nevertheless, there are indications that cannot straightforwardly be accounted for which merit attention.

At first glance, yod-coalescence appears significantly more frequent before a rhotic (sure and feature), than when there is no following /r/ (deuce). The earliest evidence in ECEP for this development is in Kenrick (Reference Kenrick1773) for sure and its derivatives only (but still en[sj]ure), and it is found in every dictionary thereafter bar Scott (Reference Scott1786), who has no yod-coalesced forms in any environment, and Burn (Reference Burn1786), though he still has a yod-coalesced form for assure. Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780), Walker (Reference Walker1791; recall from sections 2.3 and 3.1 that sure and sugar were his two stressed-syllable exceptions) and Jones (Reference Jones1797, Reference Jones1798) provide the majority of examples, but even Spence (Reference Spence1775), who has no yod-coalescence in deuce, recommends coalesced pronunciations in sure_a /s/ ([ʃ]ure, etc.), sure_b /z/ (e.g. compo[ʒ]ure) and feature /z/ (e.g. plea[ʒ]ure).

However, stressed-syllable, pre-rhotic yod-coalescence (sure_a) is almost entirely restricted to sure and its derivatives, and is barely found in /t d/, with fu[ʧ]úrity in Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780) providing the sole counterexample (probably due to its more frequent base fúture in feature with yod-coalescence, more on which below).Footnote 16 In the light of Walker's observation that sure and sugar were the only words which were coalesced in stressed syllables, where the latter did not have a following /r/,Footnote 17 yod-coalescence here appears to be a lexical effect, restricted word-initially to these two items. High-frequency may have been a conditioning factor given the very high ARCHER count (see section 4) for sure (ARCHER count: 201), although we would have to hypothesise that ARCHER does not reflect the real high-frequency of sugar (count 13) (cf. another monosyllable with initial /s/ suit (count 37) in deuce_a without yod-coalescence in any dictionary). Presumably, the propensity for /s z/ to coalesce more than /t d/ also underlies the lexicalisation of these forms. Of course, these lexicalised yod-coalesced forms remain the main pronunciations in Present-day English, unlike for other /s/-words in stressed syllables, suggesting their long establishment in the language. Disregarding sure etc., stressed syllables therefore display the same pattern of resistance as seen in non-pre-rhotic contexts (see section 3.1). However, as there are no other examples with /s/ in sure_a aside from sure and related words, it is difficult to evaluate whether the following rhotic had any facilitatory effect.

Further to this lexical effect, a second confounding factor may be secondary stress. Yod-coalescence appears to be more likely in post-stress contexts where there was a following /r/. In deuce_b, yod-coalescence in /t d/ is mostly restricted to hiatus forms (e.g. punctual), with Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780) providing almost all of the few further instances. Conversely, in sure_b, Walker (Reference Walker1791) consistently has coalescence in /t d/ (as reported in section 3.1), and is followed in this respect in some words by Jones (Reference Jones1797, Reference Jones1798), the third edition of which has no yod-coalescence in /d/ except, interestingly, in verdure. Furthermore, in feature, yod-coalescence is regular in Sheridan, Walker and both editions of Jones (aside from the /d/-forms in the third edition). One interpretation of this pattern might be facilitation by a following rhotic, but an alternative employing secondary stress is possible. Notably, every word in feature has, or has analogically acquired (Dobson Reference Dobson1957: II.852–3), the suffix -ure, which never has secondary stress in these forms in the OED or in ECEP. It is therefore unstressed, although there is variation across authors and words as to whether the suffix has a full vowel /uː/ or the vowel we have transcribed as /ʌ/ which refers to a schwa in unstressed syllables.Footnote 18 In contrast, aside from the hiatus forms (e.g. punctual), almost all the deuce_b /t/-forms have the suffix -tude, which is occasionally found with secondary stress in the OED, e.g. the US English pronunciation of magnitude. The others are opportune and bitumen, which can both have even primary stress on the /t/-initial syllable according to the OED. Furthermore, a few sources in ECEP seem to show secondary stress on -tude. Kenrick (Reference Kenrick1773), who has no yod-coalescence in any -tude form, uses ‘acute’ and ‘grave’ stress markers, the latter of which, indicating a ‘depression of the voice’, may indicate secondary stress (see Reference Kenrick1773: 46), although he is not consistent in marking it. The grave is present in amplitude and attitude, but not latitude, longitude or magnitude, and it is therefore perhaps not coincidental that Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780) has coalescence only in the latter three, but not the former two. Burn (Reference Burn1786) shows exactly the same pattern, hence may have been influenced by Kenrick. Perry (Reference Perry1775) seems much more consistent in indicating secondary stress by separating the secondarily stressed syllable with a hyphen; amplitude, attitude, latitude, longitude and magnitude all have secondary stress on the final syllable. It may therefore be the case that the (predominantly) -tude versus -ture pattern above is caused by greater resistence to yod-coalescence in secondarily stressed syllables than in unstressed ones.

Such a stress-based account would predict greater propensity for yod-coalescence in any fully unstressed syllable. However, the prediction does not seem to be borne out by the /d/-forms in deuce_b, where coalescence is almost always resisted despite the relevant syllable being unstressed and immediately after primary stress. For example, fraudulent, incredulous and glandulous show no yod-coalescence in any dictionary (see section 3.2 on module), in contrast with unstressed and coalesced (in Sheridan, Walker and Jones) verdure and ordure in sure_b with a following rhotic. We therefore conclude that the facilitatory effect of a following /r/ cannot be ruled out.

The failure of yod-coalescence in fraudulent, incredulous and glandulous beside its presence in verdure and ordure could plausibly be attributed to inhibition before /l/ – the other English liquid – as opposed to facilitation before /r/. However, coalescence patterns in /t d s z/ all behave identically before /l/ and before any other consonant bar /r/: in deuce_a, Sheridan has [ʧ]ulip beside [ʧ]unic; no dictionary has coalescence in duly or duty, or dual/duel (although these are never reported as monosyllabic) beside due; in deuce_b, consular has the same coalescence pattern as issue and tissue (although Sheridan has uncoalesced insulate); in deuce_c, neither adulation nor duplicity show any yod-coalescence. Resistance in the hiatus form gradual (only coalesced in a variant form in Walker) cannot be attributed to the following /l/, but must rather be due to a propensity of /d/ to resist coalescence (as seen in stressed syllables; section 3.2), as a comparison with the similar /t/-form punctual reveals, where Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780), Walker (Reference Walker1791) and Jones (Reference Jones1797) all report yod-coalescence as the main forms.

In fact, evidence from forms that were not included in ECEP seems to indicate that /l/ played a somewhat facilitatory role in yod-coalescence, similar to /r/, but perhaps to a lesser extent given the pattern reported above. The evidence comes from three /t/-forms which would have appeared in deuce_b (i.e. in unstressed syllables): pustule, spatula and titular. The phoneme /t/ in deuce_b usually resists yod-coalescence except in hiatus, but all three of these words are coalesced in Sheridan, Walker and Jones (both editions).Footnote 19

In post-stress forms with /s z/, sure_b and feature again show more consistent yod-coalescence than deuce_b. It is absolutely regular in both pre-rhotic sets in Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780), Walker (Reference Walker1791, with the sole exception of rasure) and Jones (Reference Jones1797, Reference Jones1798), and is regular in /s z/ in feature in Perry (Reference Perry1775). Even Spence (Reference Spence1775), who has no yod-coalescence in deuce, has /z/-coalescence regularly in feature (again except in rasure), and in composure, azure and closure in sure_b, but note the potential confound of the unstressed -ure suffix. Finally, Kenrick (Reference Kenrick1773) has coalesced /z/ forms in pleasure, measure, treasure and leisure. In contrast, there are more uncoalesced exceptions in deuce_b, for example, fully unstressed insulate in Sheridan, and casualty and casual in both Sheridan and Jones (Reference Jones1797); furthermore, only one other author aside from Sheridan, Walker and Jones reports coalesced forms: Perry with issue and tissue. Following /r/ therefore seems to have a facilitatory effect on yod-coalescence in /s z/ in fully unstressed syllables, although it must be noted that there are only three /z/ words in deuce_b, as opposed to ten in sure_b and feature combined.Footnote 20 Finally, note that feature has earlier and more yod-coalescence than sure_b, especially in /z/, e.g. before 1775 there are no examples in sure_b. The present-day difference between the two sets can therefore already be found here, with more phonological reduction in feature (see section 4).

A further indication that a following rhotic might facilitate coalescence comes from signs of divergent behaviour in Jones’ third edition (Reference Jones1798) between consonants before onset /r/ and coda /r/. The majority of forms showing coalescence have a following coda /r/, whereas those following onset /r/ generally resist the change, thus assure with [ʃjuː] but assurance with [sjuː], suture with [ʧjuː] but century with [tjuː]. The counterexamples are mostly uncoalesced forms in /t d/ in stressed syllables (i.e where yod-coalescence is less likely), such as mature and endure. It is interesting to note the absence of coalescence in /s/ in a stressed syllable in assurance, but its presence in surety (both related to the lexically coalesced sure), which latter Jones confirms had a disyllabic pronunciation and therefore /r/ in a coda. These signs of divergent behaviour, albeit small, would certainly point to following /r/ being an influence, possibly due to a stronger onset variant patterning with other consonants, while a weaker coda variant facilitated coalescence. The difference could be accounted for by recognising the variant articulations and resonances of /r/ in onset and coda position, as explored in present-day British English dialects by Carter (Reference Carter, Local, Ogden and Temple2003) and Carter & Local (Reference Carter and Local2007). Recalling that coda /r/ went on to be deleted in non-rhotic English dialects, the start of which was the development of a schwa-like transition, we could hypothesise that a ‘hyper-vocalic’ sequence [Cjuːər] with three consecutive [-consonantal] sounds was simplified through yod-coalescence to [Ccoalesceduːər]. The absence of such a salient schwa before onset /r/, which did not delete, could therefore have led to resistance of coalescence in that environment.

The final evidence for the facilitatory influence of a following rhotic comes from the yod-less forms in the earlier sources, and yod-dropping in the later ones. As noted in section 3.1, the earlier yod-less forms occurred after all phonemes in unstressed syllables before /r/, e.g. sure_b century, verdure, seizure, and featurecreature, procedure, treasure. Conversely, there are only a few isolated examples in deuce, e.g. consummate in all sources which have the word, modulate in Kenrick, casual in Buchanan. Dobson (Reference Dobson1957: II.850–3) notes that the unstressed vowel reduction that led to yod-less forms which was in evidence in the sixteenth century (/iu/ > /ə/) was more likely to occur before /r/ in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with the /iu/ form generally retained before other phonemes. At the start of the eighteenth century, there continued to be variation between yod-less forms and the yod-ful forms which had developed as a result of the change /iu/ > /juː/. We see from the earlier sources in ECEP that the yod-less forms were predominantly found before /r/, and yod-ful forms before other consonants, although we already see yod-restitution taking place, e.g. uncoalesced yod-ful forms in the -ure words ordure (Buchanan), fissure (Buchanan, Johnston and Kenrick) and nature (Buchanan and Johnston). As yod-coalescence began to take place, the first sounds affected were /s z/, stressed in sure and its deriatives, but generally unstressed, e.g. issue (Johnston variant), casual (Kenrick variant) and tonsure (Johnston variant). However, it is curious to note that the context that came to be affected by yod-coalescence most was not where there had been existing yod-ful forms, but rather precisely those forms where yod-restitution had taken place, i.e. mainly in unstressed syllables before /r/ (sure_b and feature). Yod was therefore restored only to be lost soon afterwards through coalescence, a history which appears to indicate the instability of the /Cjuː/ sequence before rhotics in unstressed syllables.Footnote 21

We entertained one possibility above as to why a following /r/ might be conducive to yod-coalescence (‘hyper-vocalic’ reduction), but another (compatible) possibility may be anticipatory assimilation to the post-alveolar tongue position of /r/. The phonetically palatalised alveolar consonant before a palatal approximant (e.g. [tʲjuː]) may be further retracted to have post-alveolar contact in anticipation of /r/ if we presume it had post-alveolar constriction, as is common in Present-day British English (e.g. Wells Reference Wells1982: I.75). This retracted, palatalised coronal phoneme would then have strong post-alveolar percepts either during its articulation (/s z/) or on release (/t d/), resulting in the post-alveolar fricatives and affricates /ʃ ʒ ʧ ʤ/. Such an account makes a testable prediction: if a post-alveloar sound at the start of a following syllable facilitates the development of a post-alveloar before yod, we might expect yod-coalescence ‘chains’, where a coalesced sound triggers further coalescence in the preceding syllable. This prediction may have some support in coalesced fiduciary and fiducial in Sheridan (and a variant in Walker): no other forms with /d/ in deuce_a aside from these two are coalesced by Sheridan or any other author (e.g. duke, duty, indubitable); the clearest difference between these two and the others is the yod-coalescence at the start of the following syllable, thus [ʃ] in -ciary and -cial; this post-alveolar tongue position may have been anticipated at the start of the preceding syllable, in turn triggering coalescence in /d/, thus fi[ʤ]u[ʃ]iary and fi[ʤ]u[ʃ]ial. A final potential piece of evidence could be the curious stressed-syllable, non-pre-/r/ yod-coalescence of /s/ in suture in Jones (Reference Jones1797), where the following /t/ in the pre-rhotic unstressed syllable is also coalesced. Therefore, in a similar vein, the post-alveolar tongue position of following /r/ might have been anticipated, bringing about rhotic facilitation of yod-coalescence.

4 Word frequency

Frequency investigations provide a good illustration of how ECEP can be a fruitful starting point to explore a phonological phenomenon. Example word frequency in the database is based on the eighteenth-century British English data available in the multi-genre historical corpus ARCHER 3.2 (535,767 words). Although we would require many more example words in each subset to reveal a robust pattern, and ARCHER reports few occurrences of most of the example words, there are sufficient data from which to observe patterns which can inform wider investigations. If a sound change is lexically diffused (Wang Reference Wang1969; Chen & Wang Reference Chen and Wang1975), frequency information can capture the state of that change mid-stream, revealing how far it has progressed across the lexicon. If the change is not of this type, we might expect frequency to play a minimal role. Furthermore, changes which target high-frequency words first have been argued to be different in their motivation from those which target low-frequency words first. Phillips’ (Reference Phillips, Bybee and Hopper2001: 123–4) ‘Frequency Implementation Hypothesis’ posits: ‘Sound changes which require analysis – whether syntactic, morphological, or phonological – during their implementation affect the least frequent words first; others [authors' comment: e.g. physiologically motivated changes] affect the most frequent words first.’ Frequency might therefore provide a window onto reconstructing the motivations for a sound change.

ECEP reveals a few interesting frequency patterns. We see that stressed-syllable yod-coalescence of /s/ (deuce_a) affects the less frequent words in Sheridan (aside from the ex- word exude; see section 3.2), from suicide (ARCHER count: 3) to sudorous (0). The higher-frequency words resist the change, e.g. suit (37), suitable (21) and suitor (5). Non-word-initial position (section 3.2) probably accounts for non-yod-coalesced assume (26) and consume (8), but higher frequency could also provide an explanation. Secondly, there are indications that the difference between sure_b and feature, based on a full vowel versus schwa in Present-day English, is conditioned by frequency: the most frequent words in sure_b are century, censure and composure with only eight occurrences each, whereas the majority of feature forms have many more occurrences, notably nature (196), pleasure (181), measure (93) and creature (80). Frequency provides a better explanation of the difference than morphology, as both sets include several forms with the suffix -ure, often immediately following the stressed syllable.

Finally, earlier yod-less forms and later yod-dropping reveals more intriguing frequency patterns. The yod-less forms in the earlier sources, predominantly found in all phonemes in post-stress syllables before /r/, seem to be words of all frequencies. Sometimes the least frequent words in an environment resist it, e.g. fissure (3) and tonsure (0) in Johnston (Reference Johnston1764) beside yod-less censure (8) and pressure (9); elsewhere, the most frequent words show resistance, e.g. nature (196) is the only yod-ful form in feature /t/ in Johnston, as is composure (8, highest frequency in this context) in sure_b /z/ in Kenrick (Reference Kenrick1773). Given the considerably higher frequency of nature than the other forms, we might speculate that the highest-frequency forms resisted yod-less reduction the most, a hypothesis that would require investigation using a wider range of evidence. If true, this would have important implications for the motivation of the change in terms of the Frequency Implementation Hypothesis, which would predict that it was a change that required syntactic, morphological, or phonological analysis (presumably recognition of the suffix -ure), despite the fact that reductions are commonly based in articulatory undershoot and temporal compression.

However, when yod-coalescence begins to replace yod-less forms in feature /z/, it appears to be the most frequent words which are affected first in Kenrick (Reference Kenrick1773) and Perry (Reference Perry1775); for example, whereas Johnston (Reference Johnston1764) has yod-less forms in all words in this context, Kenrick (Reference Kenrick1773) has yod-coalesced pleasure (181), measure (93), treasure (33) and leisure (13), but yod-less azure (1) and rasure (0); Perry (Reference Perry1775) has yod-coalesced pleasure and measure, but yod-less treasure, leisure and azure. We might therefore hypothesise that post-stress-syllable yod-coalescence affected the most frequent words first, as might be expected in a physiologically motivated change such as coalescence. Conversely, we noted above that the most frequent words resisted stressed-syllable yod-coalescence in Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780), a pattern which might be explained by competition with later yod-dropping in more frequent words (below), whose explicit avoidance might have led to retention of a conservative form with yod (note the near complementary distribution of yod-coalescence in Sheridan and yod-dropping in Scott in deuce_a /s/).

Yod-dropping in later sources is found in a stressed syllable without following /r/ (deuce_a). Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780) has the earliest example with dual, repeated in Jones (Reference Jones1797), the joint-lowest-frequency word in that context (0). However, Scott (Reference Scott1786) provides the most examples, predominantly in /s z/ although variants in /d/ are recognised: duke, duty. Strikingly, it is clearly the most frequent forms in Scott that are affected by yod-dropping, the six forms from suit (37) to suicide (3) in /s/ and presume (31) and resume (7) in /z/; compare unaffected supine (1), sudatory (0), sudorous (0) and exude (0) in /s/, and zeugma (0) and exuberant (0) in /z/. In line with this, the yod-dropped /d/ variants which Scott reports are in duke (132) and duty (93), the most frequent forms in this context. Similarly, the sole example of stressed-syllable yod-dropping in Burn (Reference Burn1786) is duly (24), a relatively high-frequency word. Yod-dropping is paralleled in US English, where it is also restricted to stressed syllables after coronal consonants, with yod-coalescence common in unstressed ones (Wells Reference Wells1982: II.247).

5 Conclusions

This investigation has gone some way to answering the research questions set out in section 1.2. With regard to diatopic distribution of variants, despite contemporary comments describing Sheridan's high level of yod-coalescence as an Irishism, we have found no evidence to support this. The only clear diatopic trend to emerge is the avoidance of yod-coalesced variants by Scottish authors, a tendency still apparent in Scottish varieties today. In the metalinguistic comments recorded in ECEP, along with other eighteenth-century sources, we found ample evidence of stigmatisation of yod-dropping in all contexts and of yod-coalescence in stressed syllables. The interaction of the different phonological influences on yod-coalescence – stress, phoneme type and rhoticity – and some extra-phonological influences (chronology, frequency) are illustrated in figure 1, leaving aside the pre-stress environment. The figure shows which dictionaries (abbreviated by the first two letters of the author's surname followed by the final two numbers of the year of publication, as in the appendices) show yod-coalescence in 50 per cent or more example words in any given environment; those which show yod-coalescence in more than one item but fewer than half of the example words are given in italics. Further restrictions are presented in brackets, e.g. Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780) generally has yod-coalescence for plosives in stressed syllables in a non-rhotic context when that plosive is /t/ and word initial, e.g. tune.

Figure 1. Summary of phonological influences on yod-coalescence

We see that there is more yod-coalescence in (i) post-stress syllables than in stressed syllables, (ii) the fricatives than in the plosives, and (iii) the rhotic context than in the non-rhotic (with the exception of plosives in a stressed syllable). Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780) appears in every cell aside from ‘stressed plosive pre-/r/’, and yod-coalescence before Sheridan is found only in fricative contexts, usually in under 50 per cent of the example words in a context. After 1780, yod-coalescence becomes more commonly prescribed, with Walker (Reference Walker1791) and Jones (Reference Jones1797, Reference Jones1798) reporting it mainly in post-stress and fricative contexts.

Figure 2 illustrates the interaction between phonological and chronological influences in earlier yod-less forms and later yod-dropping. Yod-less forms resulting from unstressed syllable reduction are found mainly from the earliest source, Buchanan (Reference Buchanan1757), up to Perry (Reference Perry1775), with Kenrick (Reference Kenrick1773) providing yod-less forms frequently and in the most environments (three of the four post-stress ones). Both Kenrick and Perry report more yod-less forms in feature than in sure_b, therefore showing an increased probability in high-frequency words. Later yod-dropping in stressed syllables without following /r/ is found mainly in Scott (Reference Scott1786), with high-frequency words clearly affected more.

Figure 2. Summary of phonological influences on yod-dropping

Our investigation has thus uncovered a number of social and linguistic factors affecting the historical diffusion of yod-dropping and yod-coalescence and has demonstrated the importance of the data provided in ECEP as evidence for historical phonology. Some questions remain, notably concerning the influence of word frequency and of rhoticity which could be better addressed with access to larger data sets, such as the digitised versions of entire dictionaries produced by the team at the University of Poitiers. As Charles Jones (Reference Jones1989: 296) notes with reference to his discussion of evidence from Henry Machyn's diary for /h/ dropping/insertion in sixteenth-century English, the multifactorial nature of the influences involved in yod-dropping and yod-coalescence serve to ‘remind us of the complexity of actual historical data and warn us against the temptation of accepting “neat” and all-embracing solutions for the phonological variation they provide’.

Appendix

• Dictionaries: Bu57 = Buchanan Reference Buchanan1757; Jo64 = Johnston Reference Johnston1764; Ke73 = Kenrick Reference Kenrick1773; Pe75 = Perry Reference Perry1775; Sp75 = Spence Reference Spence1775; Sh80 = Sheridan Reference Sheridan1780; Bu86 = Burn Reference Burn1786; Sc86 = Scott Reference Scott1786; Wa91 = Walker Reference Walker1791; Jo97 = Jones Reference Jones1797; Jo98 = Jones Reference Jones1798.

• Font code: bold = earlier yod-less or later yod-dropped; grey cell = with yod; italics = yod-coalescence; italics and underlining = yod-coalescence with yod; NID = word not included in the dictionary or included but with no pronunciation transcription.

• Variants are indicated inside brackets.

Table A1. deuce set

Table A2. sure and feature sets