Introduction

Most scholars of international relations today believe that the international order is in crisis. Haas (Reference Haas2015) suggests a gradual transformation of the international system into a post-hegemonic global governance, Acharya (Reference Acharya2014) the formation of a less centralized system based on regional level interactions, and Kahler (Reference Kahler2013) the emergence of new rising powers as moderate reformers influencing the change of international rules through the existing forums.

In the sphere of challenges to the liberal world order, Allison (Reference Allison2014) sees Vladimir Putin's annexation of the Crimea as the most visible threat to the stability and preservation of the present international order. In his view, Russia's blatant violation of international norms, backed up by military force in the absence of any conditions legitimizing its use, is indicative of an aggressive strategy designed to oppose western rules politically, culturally, and militarily (Allison, Reference Allison2017). As effectively pointed out by Krastev (Reference Krastev2014: 3), Putin's vision of the new world is one of constant escalation aimed at altering the status quo: ‘He has refused to play by Western rules. He seems not to fear political isolation; he invites it. He seems not worry about the closing of borders; he hopes for it. His foreign policy amounts to deep rejection of modern Western values and an attempt to draw a clear line between Russia's world and Europe's. For Putin, Crimea is likely just the beginning’.

What is the nature of the threats that Russia poses to the present international order? Can Russia be described as an authentic revisionist power? Is the military intervention in Crimea really just the beginning? How are we to interpret Moscow's decision to intervene in Syria?

If we assume that the rise of Putin, strengthened by his fourth presidential mandate, constitutes a factor essential to any understanding of Russian foreign politics over the last decade and its inclusion, at least at first sight, among these so-called ones rising powers, it follows that an in-depth analysis of the nature of the challenges that Moscow is making to the world liberal order will entail first of all a reconstruction of the political and strategic context in which these challenges have begun to take shape. Russia's current refusal to accept the rules of the post-bipolar system passively and therefore to comply with a redistribution of power that denies the country its previously acquired centrality is the result of a series of closely connected events that have developed since the end of the Cold War (Pisciotta, Reference Pisciotta, Clementi, Dian and Pisciotta2018).

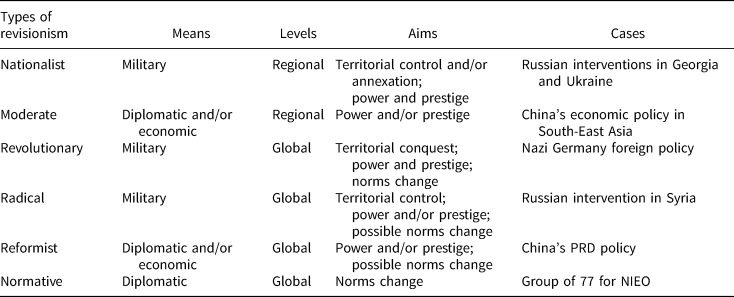

On the basis of the above premises, this paper seeks to develop a new typology of revisionism based on the nature of the aims (territorial/normative/hierarchy of prestige), the means employed (peaceful/violent), and the level of action (regional/global). This will then be used to explain the escalation of Russia's foreign policy from regional to global claims with reference to its military interventions in Georgia, Ukraine, and Syria and to identify the type of revisionism involved in each of the three Russian military interventions undertaken both inside (Georgia and Ukraine) and outside (Syria) the post-soviet space.

To this end, the paper is divided into three parts. The first examines the concept of revisionism and suggests a classification of six kinds in relation to the means, nature, and level of the claims put forward by revisionist powers. The second discusses the interventions carried out by Russia within its regional area (in Georgia and Ukraine) and highlights their similarities in light of the predominant model of revisionism. The third analyses the military intervention in Syria and notes both the escalation in the projection of Russian claims from the regional level to the global and the type of revisionism involved.

The concept of revisionism: theoretical questions

As is known, the literature has always emphasized the temporary character of hegemony, drawing attention to the fiscal crisis of the dominant power (Gilpin, Reference Gilpin1981), the transition from the waning to the rising power (Organski and Kugler, Reference Organski and Kugler1980), the long cycles determined by the succession of hegemonic wars (Modelski and Thompson, Reference Modelski, Thompson and Modelski1987), and the gap between internal political, demographic, or economic changes and international position (Doran, Reference Doran, Doran, Modelski and Clark1983). In the various historical eras, hegemonic wars have often resulted in the challenger taking over from the declining power, as in the cases of the Netherlands and Britain in the 18th century and the two European powers, France and Great Britain, and the two extra-European powers, the United States and the Soviet Union, after the Second World War.

Davidson (Reference Davidson2006), on the other hand, suggested that the balance of allied resolve, in terms of balance of capabilities between allied and adversary alliances, is central to explain the origins of revisionist and status quo states. In his view, ‘a favourable balance of allied resolve will encourage rising states to revise the status quo and will encourage declining states to maintain it’ (p. 20).

Given these premises, the first major methodological task is to identify the conditions that enable a power dissatisfied with the status quo to switch from passive acceptance of the established international order to active support of its national interests and claims. The transformation from a simple rising power to an authentic revisionist power presupposes the determination to use force to alter the balance of power (Schweller, Reference Schweller1994, Reference Schweller2015; Mearsheimer, Reference Mearsheimer, Dunne, Kurki and Smith2006). In the existing literature on international relations, a revisionist power is one that threatens to destabilize the international order, to upset and undermine the prevailing rules, and norms of the international community (Chan, Reference Chan2004).Footnote 1 As pointed out by Barry Buzan, ‘If stability is the security goal of the status quo, then change is the banner of revisionism. (…) Revisionist states, in other words, are those that find their domestic structures significantly out of tune with the prevailing pattern of relations, and which therefore feel threatened by, or at least hard done by, the existing status quo. Because of this, revisionist states tend to view security in terms of changing the system, and/or improving their position within it’ (Buzan, Reference Buzan2008: 241).

The division of powers into champions of the status quo and revisionism in terms of stability and change does not exhaust one of the thorniest questions in international relations. On the one hand, the problem remains of securely identifying the states dissatisfied with the current status quo and potentially prepared to challenge the norms and rules of the international order. On the other hand, it cannot be taken for granted that the dominant power must therefore always be satisfied with its position and immobile. As regards the first point, for example, the intense debate on whether China and Russia are to be correctly interpreted in the present international system as status quo or revisionist powers is highly indicative. John Ikenberry argues that the military capacity of China and Russia (and Iran) is not sufficient to undermine the stability of the liberal international order and that they are therefore part-time spoilers rather than full-scale revisionist powers (Ikenberry, Reference Ikenberry2014). Walter Russell Mead argues that Russia and China (and Iran) never bought into the geopolitical settlement that followed the Cold War and are making increasingly forceful attempts to overturn it (Mead, Reference Mead2014).Footnote 2

The definition of the USA as the paradigmatic example of a status quo power appears equally controversial. While theorists have highlighted the ability and desire of rising states to transform the system, it follows that precisely the hegemonic powers ‘are best positioned and most motivated to be revisionist powers’ (Schweller, Reference Schweller2015: 13).Footnote 3

Another fundamental aspect of revisionism, on which debate is still under way in the internationalist literature, regards the nature of the objectives of a possible change in the status quo and the means with which they are pursued. In short, what objectives justify the inclusion of a certain country in the category of revisionist powers? Moreover, taking it for granted that such objectives certify the presence of revisionist intentions, what difference is there between a country that pursues its objectives by means of force and one that instead uses diplomacy and economic cooperation?

Buzan (Reference Buzan2014) has developed a typology of revisionism grounded primarily on the degree of change sought by the state in question and identifying three major types: orthodox, bound up with the improvement of status through policies of self-promotion that have no direct effect on the international distribution of power and preserve the rules of the system unchanged; revolutionary, which involves complete transformation of the rules and hierarchy of the system and challenges the status quo in markedly ideological terms; and radical, an intermediate position characterized by desire to change the rules within the existing framework of international society but without any revolutionary aims.

It follows from the above that the nature of revisionist aims can involve changes in norms, regimes, territory, and the hierarchy of prestige. Some domains of revision are therefore more dangerous than others. There is a qualitative difference between territorial revisionist aims and those pertaining to changes in norms or regimes: ‘Dissatisfaction with the division of territory, borders, or spheres of influence has been shown to be a “most likely” cause of interstate war. Unhappiness over the nature of global governance structures (norms and regimes), by contrast, is far less likely than territorial disputes to lead to large-scale violence or the need to resort to the battlefield for their resolution. Emerging powers can circumvent most established international rules and norms without resorting to or provoking the use of force. (…) Like norm violation, prestige demands need not result in war; they can often be satisfied by providing the emerging power with a seat at the table’ (Schweller, Reference Schweller2015: 10).

The presence of a threat, its specific nature, the means that the revisionist power is willing to deploy, and its determination to achieve its aims make it possible to compile a sufficiently exhaustive profile of revisionism. On this point, Schweller (Reference Schweller2015: 8) argues that ‘there are four dimensions to revisionism that, taken together, determine whether the revisionist state poses a dangerous threat to the established powers and to what degree: (1) the extent of the revisionist state's aims; (2) the revisionist state's resolve and risk propensity to achieve its aims, (3) the nature of its revisionist aims (does it seek changes in international norms, or territory, or prestige); and (4) the means it employs to further its revisionist aims (whether peaceful or violent)’.

A new typology of revisionism

In addition to the nature of the revisionist objectives (territory, international norms, or prestige) and the means employed (violent or peaceful), there is another crucial aspect that the literature has not taken into account: the level of action, which can be regional or global. As we'll see, this aspect is crucial for the development of a new typology of revisionism.

At the regional level, the intent to control or annex a territory, reformulate the norms, modify the regional structure, or alter the hierarchy of prestige is confined exclusively to the regional area in which the revisionist power is located. More specifically, the regional area delimits the actions that a state can decide to undertake with respect to the countries dependent on it and/or geographically, economically, and culturally involved in relations with it. The degree of danger of the threat of possible changes to the status quo is a reflection of regional balances of power and directly affects the neighbouring states and those located in the area. The Chinese policy of investments in South-East Asia and Russia's economic, energy, and military policy towards the former Soviet republics provide two excellent examples of action confined to the regional level.

When the demands of the revisionist power extend beyond its regional area, the challenge can instead involve the dominant global power (or powers) directly with the risk of limiting or compromising its (their) strategic interests and spheres of influence at the global level. In this case, unlike the previous one, the action undertaken by the revisionist state, be it peaceful or violent, tends to go beyond the boundaries of its regional area and extend to the international order, thus affecting the international norms, the hierarchy of prestige, the distribution of power and the control or conquest of territories, neighbouring, and otherwise. It is known that the regional and the global levels are both ‘external’ with respect to national boundaries (Pisciotta, Reference Pisciotta2016). In order to avoid misunderstandings, here we prefer to use the term ‘global’ rather than ‘international’ to stress the difference between a geographically delimited space (regional) and a potentially open space (global), by definition exposed to any external factor (regional, international, transnational).

The three dimensions of revisionism, namely the level of the aims (regional or global), their nature (territory/norms/power/prestige), and the means employed (violent or peaceful), can thus be used to develop six different kinds of revisionism as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Typology of revisionism

This typology contains two new elements with respect to those formulated in the past. The first regards the introduction of the level of action (regional/global) undertaken by the revisionist state. As we shall see below, this dimension is of crucial importance to highlight the gradual escalation of aims and the means employed, especially when there is recourse to military force, in transition from the regional to the global level. The degree of danger of the threat to the status quo is directly proportional to the level at which action is undertaken. In the present international system, where various actors would find it in their interest to counterbalance US hegemony but lack the means to do so, it is of crucial importance to note the presence of an actor that has no hesitation in resorting to military force in the pursuit of its own interest outside its regional area and without the consent of the hegemonic power.

The second regards the relation between means employed, level of action, and objectives. If all three dimensions work simultaneously to determine the type of revisionism, it is possible to compare the different empirical cases and highlight similarities and differences between the different forms of foreign policy, which would collapse if there were no connections between their objectives, means, and level of action. For example, two countries can both pursue the aim of changing the hierarchy of international prestige, and therefore act at the global level, but may choose to use force or diplomacy. It is true that the degree of threat to the status quo can be equally high, especially when the action undertaken proves more underhand and less visible, but the use of military force, being more explicit and devastating, can require equally explicit and devastating means in order to restore the status quo. Moreover, the use of military force outside a country's regional area can be associated both with objectives of territorial conquest, the pursuit of hegemony and a complete change in the status quo, and with objectives of mere control over zones of strategic importance together with the security of national borders and increase in power and prestige. There is evidently a substantial difference between these two kinds of revisionism and hence a drastic difference in the level of the threat to the status quo. Equally different are two forms of foreign policy that both opt for the use of peaceful means but pursue markedly different objectives at the global level, such as changing international norms or regimes on the one hand or the hierarchy of power on the other. While both can produce substantial change at the global level, it is clearly only the second type of revisionism that can potentially affect the distribution of power.

In this framework, nationalist revisionism, radical revisionism, and revolutionary revisionism represent three forms of change in terms both of expansion and of control over territory on the part of the revisionist power. All three presuppose the use of military force and objectives of power and territory with a gradual escalation in the degree of change pursued. The first (nationalist) involves forms of territorial expansionism or annexation with respect to neighbouring countries for the improvement of power and prestige at the regional level. The second (radical) is an intermediate modality of change in prestige and/or power at the global level, with or without any intention to alter the international norms, through the acquisition of the part of the revisionist state of territorial control over areas that are geographically distant but regarded as strategically vital to its national interests. The third and most extreme (revolutionary) is based on military conquest and the overall redistribution of power, rules and territory at the global level. The (nationalist) Russian military interventions in Georgia and Ukraine, the (radical) Russian military intervention in Syria, and the (revolutionary) foreign policy of Nazi Germany are three examples of each of the type put forward. It should be pointed out that in the typology presented here, only revolutionary revisionism – which should hopefully constitute no more than a text-book hypothesis in the current situation – corresponds to the kind identified by Buzan, while our radical revisionism is very different in meaning from his. Anyway, here we prefer to use the same term because it is the most appropriate to express our type of revisionism.

Moderate revisionism, normative revisionism, and reformist revisionism indicate three kinds of foreign policy pursued with non-military means of diplomatic and/or economic nature and again involve a gradual escalation of objectives and radius of action. A state may decide to strengthen its position at the regional level through a whole gamut of policies ranging from diplomatic or commercial relations with bordering and/or culturally similar states to the imposition of agreements highly advantageous to its national interests (moderate revisionism). It may decide to undertake large-scale diplomatic action at the global level to modify certain norms and rules of the international system in order to reduce the economic, social, and political costs they involve for the country (normative revisionism). It may use diplomatic and financial means to improve its power and/or prestige at the global level and even pursue a change in international norms (reformist revisionism). The policy of investments adopted by China in the less developed countries of South-East Asia (moderate), the aspirations of the Group of 77 for the NIEO (normative), and the Chinese policy of peaceful/rise/development at the global level (reformist) are examples of the three kinds of revisionism listed above.

Since every kind of revisionism always seeks a change in the status quo, differing in intensity but in any case always substantial, it follows that even when economic means are employed to attain the set objectives, the effects produced are anything but mild. On the basis of this assumption, the typology put forward here can provide an effective heuristic tool for two reasons. First of all, the close relationship between means and objectives makes it possible to delimit the sphere of application of the concept of revisionism and confine it in most cases solely to states possessing sufficient military and economic resources to be able to aspire realistically to a change in the regional status quo and hope to strengthen their position with respect to the hegemonic power at the global level. The weaker states will therefore hardly be able to pursue any form of revisionism other than the normative with any reasonable probability of success.

Secondly, the distinction between the regional and global levels makes it possible not only to reconstruct an escalation of objectives as regards change in the status quo but it is also possible to identify a predominant level of revisionism that characterizes an entire phase of foreign policy and is the result of a series of more or less interconnected individual actions when the fundamental objective of the state tends to remain comparatively stable over time. If this does not happen, it may prove more useful to determine the different facets that emerge from the discontinuity of a specific phase of foreign policy through analysis of the individual decisions taken.

Undue importance should not be attached to any discrepancy between reformist and radical actions, as the use of military force, once adopted at the global level, drives the desire for change in a direction from which it is not always possible to turn back and that tends to characterize a foreign policy far more strongly than simple reformism. In this case, the connection between means and objectives emerges from the notion of ‘uncertainty’ introduced by Schweller with reference to the decision of a revisionist state to resort to force. According to the author, this uncertainty arises from the effective military capacity of the revisionist state with respect to that of its potential allies and the adversary, the importance of what is at stake for both sides in the conflict, and the possible involvement of other actors. Schweller argues that this is a crucial criterion for the identification of actors as risk-acceptant and risk-averse: ‘Risk-acceptant actors are gamblers, while risk-averse actors are cautious under conditions of uncertainty. Risk-acceptant leaders, because they attach some added utility to the act of taking a gamble, are less constrained in making war decisions than are risk-averse actors; they are the actors most likely to saber-rattle, to ruthlessly engage in greedy expansion, and to anticipate bandwagon effects’ (Schweller, Reference Schweller2015: 10). If risk acceptance thus constitutes a key determining factor within the sphere of revisionism, it follows – as Schweller argues – that risk-acceptant and revolutionary powers are the most virulent expanders.

Although theoretically the military option however represents a risk, in the analysis of Russian foreign policy the reference to this concept simplifies the understanding of the nature of the revisionist aims, especially in terms of nationalist claims, as we will see in the Ukrainian case. The following empirical analysis seeks to explain the nature of the Russian military interventions in Georgia, Ukraine, and Syria with reference to two central aspects: (1) the gradual escalation of Russia's objectives from the regional level to the global and (2) the classification of the three military interventions in terms of the typology of revisionism put forward here.

Regional military interventions: Georgia and Ukraine

Putin's declaration in his state of the nation speech on April 2005 that the collapse of the Soviet Union was ‘the greatest geopolitical catastrophe’ of the 20th century (news.bbc.co.uk, Putin deplores collapse of USSR, accessed 10 January 2018) helped to eliminate many doubts as to whether Russia was a power dissatisfied with the present status quo. Despite Putin did not mean to praise the USSR but just to deplore the Russian diaspora, his message seemed very explicit. Anyway, as we saw in the first section, this question is not yet peaceful. As we shall seek to show in our empirical analysis, it is possible to explain the rationale of Russia's military intervention on the basis of a more neutral assumption that seeks to ascertain the pursuit of any revisionist objectives and to delimit their sphere of application – regional or global – in relation to the radius of action and the consequences produced. In other words, the important thing is to detect the means used and the presence of objectives regarding change in the status quo.

If we are to explain the predominantly regional dimension of the Russian revisionist strategy implemented through the military interventions in Georgia and Ukraine and, at the same time, to define the nature of Moscow's objectives within the sphere of the post-Soviet area, three questions must be answered. Why did Russia opt for military force in Georgia and Ukraine? Why should these two military interventions be classified as part of a revisionist strategy of the regional kind? What is the nature of the Russian revisionism manifested in these two cases? To this end, our empirical analysis will focus on the choice of means, the level of action, and the objectives pursued.

Choice of means

The answer to the first question depends first and foremost on the stakes involved. The Russian leadership assessed the risks connected with uncertainty over the outcome of the conflict as far lower than the costs otherwise involved: (a) allowing Georgia to regain control over Ossetia and Abkhazia, strengthen its position with respect to Russia and intensify its relations with NATO; (b) accepting a pro-western democratic shift in Ukraine that would detach it definitively from Moscow and place it in the hands of the EU and NATO; and (c) failing to halt the international decline that set in with the collapse of the USSR, which would not only prevent the country from improving its prestige but also force it into passive acceptance of European and American expansion within its regional area. Counting on western non-intervention both in Georgia and in Ukraine, Russia showed a new image of itself as a country capable of taking military action in defence of its national interest and above all willing to accept the political and military risks entailed by the use of force at a price that has proved comparatively acceptable, as we shall see.

A necessary but not sufficient condition for any understanding of Russian strategy on the strictly military level is the gradual increase in military spending over the last decade (Table 2).

Table 2. Russian military expenditure in constant (2016) US$ m. (1992–2018)

After a significant decrease during the nineties, military spending has regularly increased: it practically doubled between 2006 and 2016 and increased again in 2018, despite the considerable cut in 2017. The aim of rebuilding, strengthening, and modernizing the army subsequent to the dismemberment of the Soviet armed forces was carried out through a series of programmes of military reorganization and modernization of the defence industry as from 2008. The aim of the State Armament Programme (SAP-2020) was the creation of armed forces capable of coping with the military needs of the post-Cold War period and undertaking military action on a small scale but a number of different fronts in the sphere of counter-insurgency operations and under conditions of asymmetric warfare (Barabanov et al., Reference Barabanov, Makienko and Pukhov2012). At the end of 2017, Putin approved Russia's State Armament Programme for 2018–27 (SAP-2027), designed to secure transition of the Russian military to a more regular procurement schedule, improve technological capability (anti-ship missiles, electronic warfare, air defence), and narrow the gap in areas such as drones and precision-guided munitions, despite continuing to lag behind in a few areas such as surface ships and automated control systems (Gorenburg, Reference Gorenburg2017).

Even though the conflict with Georgia took place in August 2008, that is, in the initial phase of this process, the accidental and unplanned nature of the military operations constituted in this case an important test to assess the efficiency and capacity for reaction of the Russian armed forces, which were reformed also in relation to their performance against the Georgian army (Bartles and McDermott, Reference Bartles and McDermott2014). Despite Moscow's military and covert action in support of secessionist movements as from 1992, this was in fact the first time since the fall of the Berlin Wall that Russia had taken direct military action against another independent state in its regional area.

Russia's rapid military intervention, commenced on 9 August and concluded on the 15th, was justified by the leadership as a defensive action to counter a surprise attack launched by Georgia on South Ossetia and to ensure the safety of the Russian citizens resident in the area. The intervention demonstrated a trade-off in terms of costs and benefits sharply in favour of the use of force. If the western policy of appeasement avoided the political costs of international isolation, loss of prestige and/or reliability, and possible economic or military sanctions, the military costs were amply covered by the overwhelming asymmetry of the forces involved. According to the estimates of the Russian military analysts, partially corrected by the US State Department, the war between Russia and Georgia saw some 35,000–40,000 Russian and allied forces, augmented by significant air and naval forces – 200 fixed-wing aircrafts, 40 helicopters, 300 combat aircrafts, and the Black Sea Fleet ships – confront some 12,000–15,000 Georgian forces with little air and no naval support (Cohen and Hamilton, Reference Cohen and Hamilton2011).

The foregone success of the operations in the field, eliminating any uncertainty as to the outcome and all military risk, enabled Russia to secure a series of territorial and strategic objectives obtainable only through military intervention:

(1) expelling Georgian troops and effectively terminating Georgian sovereignty in South Ossetia and Abkhazia;

(2) preparing the ground for the independence and eventual annexation of these separatist territories;

(3) undermining Georgia militarily and politically, and destroying its western ambitions;

(4) sending a strong message to its neighbours that their claims against Russian national interests may lead to war and/or their dismemberment;

(5) increasing its control of the Caucasus, especially over strategic energy infrastructures like the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan oil pipeline and the Baku–Erzurum gas pipeline.

To summarize, Russia's military intervention in Georgia constituted the first element of discontinuity in the post-Soviet sphere, demonstrating the country's determination to alter to its own advantage the status quo emerging on the collapse of the USSR both by regaining control over territories previously belonging to the Soviet Union and by inaugurating a less inhibited foreign policy open also to the use of force in order to achieve regional objectives.

On the strength of the success already obtained in Georgia and the reinforcement of its armed forces during the interval between 2008 and 2014, Russia again launched a military intervention in Ukraine. In this case, however, the military option involved far greater political and economic costs for Russia. As is known, the UN General Assembly Resolution A/RES/68/262 asserted the need to safeguard of territorial integrity of Ukraine and the invalidity of the referendum on the Russian annexation of Crimea (http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/68/262). The EU imposed a series of restrictive diplomatic and economic measures against Russia in March 2014, which have been extended until 31 July 2019.

Even though some aspects of Russia's intervention in Ukraine are still somewhat unclear, this operation, unlike the one in Georgia, was skilfully studied and planned in detail by a small circle of Putin's associates with the precise intention of taking by surprise not only the Americans but also part of the Russian leadership and the Ukrainian Security Service (Bartles and McDermott, Reference Bartles and McDermott2014). Some sources maintain that Russia probably had some form of contingency planning for a Crimean annexation and that preparations for the campaign began days or weeks before Yanukovych's escape (Cathcart, Reference Cathcart2014). The operations in the field, from 26 February to 18 March 2014, received a wide media coverage and were characterized by an intense propaganda and a systematic strategy of disinformation (Richey, Reference Richey2018). These carried out with a few units of the Russian Rapid Reaction Forces Command – the Russian Military talked about 1000 men, Kyiv asserted that there were several times more (http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/russia/sbr/htm Accessed 18 January 2018) – enabled Russia to seize control, quickly and with little bloodshed, of the airport, the major television stations, and the military bases in the Crimea (Bartles and McDermott, Reference Bartles and McDermott2014: 56).

If Putin assessed the costs of the use of force as lower than the benefits, being able to count on western non-intervention as well as the weakness and lack of preparation of the Ukrainian armed forces, aspects that recall the previous situation of asymmetry in Georgia, it is also true that the increase in military expenditure and SAP-20 proved essential to the positive performance of Russia's special forces in Ukraine.

At the economic level, at least in the short and medium terms, the effects of the sanctions imposed by the EU have continued to weigh on the Russian economy's prospects for growth and development (see later). This does not, however, alter the fact that the military option enabled Russia once again to obtain results of great importance in territorial and regional terms:

(1) the annexation of a strategic territory like Crimea;

(2) consequent control over the military base of Sevastopol and the Black Sea region;

(3) the weakening of Ukraine in both territorial and political terms;

(4) a halt to the road of Ukraine to the EU and above all the possibility of its joining NATO;

(5) a demonstration of the capacity to engage in asymmetric warfare, a form of warfare that combines the use of conventional and unconventional force and the use of force with non-military tools of war (cyber, economic, political, and information war programme (Bukkvoll, Reference Bukkvoll2016);

(6) a demonstration of the high level of training, efficiency, and discipline of the Russian Rapid Reaction Forces Command.

Even though the rest of the rank and file experienced the same problems as in 2008, the successful performance of the Russian Rapid Reaction Forces was crucial to the expansion of Russian ambitions in the post-Soviet space. If Russian intervention in Crimea was to require a very different and more sophisticated approach from the typical heavy-handed operations conducted by Russia's armed forces in Chechnya and Georgia, it is important to emphasize how the weakness of the Kyiv government and the Ukrainian military and security forces, a potentially friendly and Russian-speaking environment, and basing rights in Crimea, with the Russian naval presence in the form of the Black Sea Fleet, played a crucial role in enhancing Russian power in the Black Sea region (Bartles and McDermott, Reference Bartles and McDermott2014).

Level of action

As regards regional dynamics and the importance attached to geopolitical and strategic factors in shaping Russia's foreign policy, the literature has underscored the central part always played by Russia's resolute opposition to western expansion in the post-Soviet area (Mead, Reference Mead2014; Mearsheimer, Reference Mearsheimer2014; Tsygankov, Reference Tsygankov2015). The Russian leadership had repeatedly manifested its opposition to American and European interference in the internal affairs of the post-communist countries both by opposing the rationale of the coloured revolutions and by active intervention to remove any leaders adopting a foreign policy independent of Moscow. In the Russian vision, the expansion of NATO on the eastern front, and especially the possibility of Georgia and Ukraine joining the Atlantic Alliance, would irreparably compromise the use of its bases located along a cordon sanitaire that runs from Belarus to Ossetia and constitutes the last bulwark to defend the territory of the Federation from external threat.

Russian concern over NATO expansion on the eastern front is constantly reiterated in the official documents (Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation, FPCRF, 2008, 2013, 2016).

Russia's sense of being encircled by the West was accompanied by the fear of being unable to halt the relentless decline of the 1990s. In their efforts to achieve this and to improve the country's regional prestige in the medium and long term, Russian leaders realized that their country was facing a negative shift in future bargaining power and tried to reduce this source of insecurity by using Eurasian integration as a form of regional balancing. In this perspective, Russian efforts to rearrange the institutions of regional order clashed with the US foreign policy in East and Central Europe: if the conflict in Ukraine just happened to be where the Russia's efforts to attract Ukraine by offering Kyiv preferential access to Russian markets and discounts on gas imports failed against EU competition (Krickovic and Weber Reference Krickovic and Weber2018), the military intervention in Georgia was strongly influenced by Russian views about its entitlements within the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) region (Allison, Reference Allison2009).

By intervening in Georgia and Ukraine, Russia thus manifested its true intentions to the world as a whole: to strengthen its position with respect to neighbouring countries; to regain territories lost in the dismemberment of the USSR; to assume the recognized and unchallenged role of dominant regional power in the sphere of a space of Eurasian integration; and above all to put an end to US expansion in the post-Soviet space. The last point in particular encapsulates the intrinsic sense of the entire phase of Russian foreign policy beginning with the Georgian conflict and ending with the annexation of Crimea. The answer to the question of why the interventions in Georgia and Ukraine are to be regarded as part of a revisionist strategy of the regional type is provided precisely by their rationale: to prevent the USA from continuing its expansionist strategy in East Europe and to make it understood that any interference in the post-Soviet area would be countered by all the means available including the use of force. The military operations in Georgia and Ukraine did not challenge American hegemony at the global level but are rather to be seen as an explicit attempt on the part of Russia to halt its decline by reinforcing its supremacy within its regional area with respect to the neighbouring countries and drawing a clear line of demarcation between the post-Soviet space (Russia's bailiwick) and the rest of the world (still subject to American hegemony). While it is of course impossible to rule out the possibility that the annexation of Crimea also had an international impact, at least in terms of unintended consequences of the action carried out, it is very hard to evaluate precisely the scale of these effects, above all given that the Russian interventions did not affect territories already controlled by the USA but rather halted America's attempts to disseminate its political model and enlarge its sphere of influence.

On this view, Russia acted realistically in Georgia and Ukraine, moving like a revisionist power inside the post-Soviet space, which was only partially under its control before 2014. Russia certainly altered the status quo by annexing further territories to the Federation; taking control of regions of strategic importance for its political, economic interests, and energy requirements; and carving out a margin of action such as to place its regional space off-limits. What Russia did not do was send its troops outside its regional area. In other words, Russia was still playing on its home ground in Georgia and Ukraine.

Objectives

The analysis developed so far as regards the choice of means and level of action has made it possible to highlight various aspects that appear to confirm the nature of Russia's interventions in Georgia and Ukraine as falling within the category of nationalist revisionism: (1) acceptance of the inherent risk involved in the use of force; (2) the presence of objectives of a territorial nature to be attained through annexation and/or control over strategic areas; (3) the presence of symbolic objectives connected with halting the decline of the 1990s and improving the country's prestige at the regional level; and (4) the regional dimension of the revisionist strategy pursued through the military, territorial and political strengthening of Russia with respect to its neighbouring countries, the safeguarding of its security, and the demarcation of its sphere of action through resolute opposition to any expansion of NATO.

Besides the strictly external factors influencing Russian foreign policy during the last decade, such as the attempt to strengthen Eurasian integration within the post-Soviet space and to ward off the spectre of NATO enlargement, as we have seen, the literature has also examined the impact of internal cultural and socio-political variables such as the nationalist matrix of Russian foreign policy and the historical, cultural, and affective links between Russia and its former republics (Clover, Reference Clover2016).

Toal (Reference Toal2017), for example, prefers the term revanchism to revisionism as a description of Putin's attempts to strengthen Russia's position inside and outside its borders. While he sees this project as a clear expression of determination to regain past position, power, and prestige, its rationale disregards territorial expansion and reflects the unfolding entanglement with pre-existing territorial disputes in the Caucasus and Ukraine. The roots of the revanchism stretch a long way back through the imperial vision of ‘Greater Russia’, the Bolshevik model of ethno-territorial federalism based on different national forms brought into line by the same socialist content, to arrive on the ruins of communism and reappear in the guise of a strong Russia in control of the complex post-Soviet space to protect a threatened vital interest.

The national question has provided recurrent justification for the use of military force (Treisman, Reference Treisman2016), as Russia's ambition to consolidate a regional political bloc among the CIS is closely related to its determination to protect Russian minorities from the Baltic to the Black Sea (Laruelle, Reference Laruelle2015). In this connection, Russian rhetoric has not failed to underscore these aspects, as confirmed by the declarations of the then prime minister Medvedev after the annexation of the Crimea, which effectively identify the criteria defining the Russian-speaking community and extend them to the pre-revolutionary and Soviet borders: ‘We are talking about people whose relatives or themselves have lived permanently in Russia, as well as in territories that belonged to Russia before the (1917) revolution, or were part of the Soviet Union’ (Najibullah, Reference Najibullah2014). This is echoed in the statements of Putin reported in the New York Times on 18 March 2014: ‘Crimea has always been an integral part of Russia in the hearts and minds of people. (…) After a long, hard and exhaustive journey at sea, Crimea and Sevastopol are returning to their home harbor, to the native shores, to the home port, to Russia! (…) Millions of Russians went to bed in one country and woke up abroad. Overnight, they were minorities in the former Soviet republics, and the Russian people became one of the biggest – if not the biggest – divided nations in the world’.

Chapter III of the 2008 FPCRF, under the heading International Humanitarian cooperation and human rights, lists the country's objectives with explicit reference to its determination to protect the ‘rights and legitimate interests of the Russian citizens and compatriots living abroad’. The document of 2013 reasserts and emphasizes Russia's determination to safeguard its citizens in other countries and adds among the Regional Priorities a specific intention to support the republics of Abkhazia and Ossetia (FPCRF, 2013). The document of 2016 refers to Russia's cultural and spiritual ties with Ukraine as well as the desire to construct a partnership relation in line with Russia's national interests (FPCRF, 2016).

Even though the justification Russia has offered for its actions is still hotly debated (Ziegler, Reference Ziegler2012; Allison, Reference Allison2014; Averre and Davies, Reference Averre and Davies2015; Rae and Orchard, Reference Rae and Orchard2016), the crucial element for the purposes of our analysis is the close connection between territorial claims and ethnic identity. In other words, Russia may have exploited the nationalist issue to its own ends, taking advantage of the principle of responsibility to protect, but the crises under way both in Georgia and in Ukraine did involve Russian citizens. In this respect, the objective of safeguarding the rights of Russian minorities in the post-Soviet space as a whole received clear empirical confirmation in the actions undertaken by Russia in the two countries. With regards to means, sphere of action, and objectives, the strategy pursued by Russia in Georgia and Ukraine ultimately confirms both the regional dimension of the interventions and their definitive inclusion in the category of nationalist revisionism. Even though the two interventions are very different in historical, political, and military terms, as we have seen, they both confirm the presence of objectives regarding territory (control/annexation of South Ossetia and Abkhazia; annexation of Crimea), power, and prestige (improvement of Russian position at the regional level).

While Russia was still acting at the regional level in Georgia and Ukraine, as we shall see, Syria marked transition to the global level.

Global military intervention: the case of Syria

The operation in Crimea constituted a formidable springboard enabling Putin's Russia to escalate from the regional to the global level. This transition is of crucial importance because it marks a clear line of discontinuity with the previous phase of Russian foreign policy. Unlike the interventions in Georgia and Ukraine, the action in Syria has had direct effects at the global level as regards both the use of military force outside the post-Soviet space and the scale of the challenge to the balance of power at the global level. By choosing not only to fight against the Islamic State but also to safeguard the Syrian government, Russia openly opposed America's interests in the area. In order to explain the dynamics and the consequences of the Russian intervention in Syria, our empirical analysis will adopt the same framework as for Georgia and Ukraine, examining the choice of means, the level of intervention, and the objectives pursued.

Choice of means

Why did Russia opt for military intervention in Syria? In his statement to the UN General Assembly 2 days before the Russian aircraft arrived in Syria, Putin declared that IS expansion to other regions was ‘more than dangerous’ and that no one but the Syrian armed forces and the Kurds were ‘truly fighting the Islamic State and other terrorist organizations in Syria’. The fight against terrorism has unquestionably always constituted a priority of Russian domestic and foreign policy, as demonstrated by the references made in the 2016 FPCRF.

In this connection, the literature has not failed to underscore the centrality of the fight against terrorism of a key Russian objective, as we shall see, without underestimating the importance attached in Russian strategy to preserving the territorial integrity of the Syrian state and the consequent support for Assad. Strengthening the Syrian government's forces, Russia was unable to maintain the agreements guaranteeing its strategic interests as regards the supply of military equipment and energy to Syria as well as the enlargement of the Russian naval base in the Mediterranean port of Tartus.

There is, however, another substantial factor involved, namely the explicit request for Russian intervention made by Assad when military operations were definitively compromising the position of the Syrian government forces. Given the request for help, which justified Russia's intervention at least in the eyes of the Kremlin despite the criticisms expressed by the USA, Moscow was only called upon to bear the economic costs of the operation. On this point, the first thing that needs to be considered is the sustainability of the Russian economic effort. The decrease of oil price, together with the European sanctions against the action in Ukraine, proved quite severe for Russia, contributing to a drop in GDP from 2297 trillion in 2013 to 1283 trillion in 2016 (World Bank, 2017). Therefore, it was in Russia's interests to reduce its economic commitment in Syria as much as possible. The help given to Assad was nevertheless considerable, however, above all through the supply of air support. According to estimates, between 30 September 2015 and 14 March 2016, Russia deployed in Syria a dozen Su-24s, Su-25SMs and Su-25 UBMs, four Su-30 fighter jets, and six Su-34s, starting with 20 sorties per day and increasing to over 60 per day when the ground operations were under way. The number of ground troops has been calculated as between 1700 units at the beginning of the intervention and 3000 at the end, supported by Russia's Mediterranean squadron of about 10 ships on rotation (Kofman, Reference Kofman2015).

In military terms, the intervention in Syria enabled Russia to attain the following objectives:

(1) to strengthen the Syrian government;

(2) to weaken the rebel forces and the position of the Islamic State;

(3) to demonstrate its capacity for military intervention also outside its regional area;

(4) to take part as a great power in future peace negotiations;

(5) to obtain permanent access to the port of Tartus, located in a strategic position for control over the area of the Middle East. Under the terms of the recent 49-year agreement signed by Russia and Syria in January 2017 and ratified by the Duma in December, Syria grants Russia free use of various zones in the harbour area of Tartus and access to Russian nuclear-powered warships.

In short, the strategic, political, and military advantages obtained by Russia through intervention in Syria have proved markedly greater than the economic costs of the entire operation.

Level of action

As regards the level of action, the first element to be considered is Russian dissatisfaction with the current international order and its determination to secure fundamental changes. These include transition to a multipolar system, respect for sovereignty and non-interference in the internal affairs of other states, and a fair international system that addresses international issues on the basis of collective decision-making.

The escalation of Russian demands from the regional to the global level is confirmed not only by the deployment of aircrafts outside the post-Soviet space but also and above all by the new perception Russia has developed over the last decade as regards the structure of the international system and its own place within it. Comparison of the objectives and assessments of the FPCRF for 2008, 2013, and 2016 proves illuminating in this connection. While all of these documents include the priority objective ‘to consolidate the Russian Federation's position as a centre of influence in today's world’, Russia's view of the nature of the system changes. In 2008 Russia stressed the ‘need for the international community to develop a common vision of our era’ and deplored the fact that the ‘unilateral action strategy leads to destabilization of the international situation’ (FPCRF, 2008). One year before the annexation of Crimea, it was noted that the ‘ability of the West to dominate world economy and politics continue to diminish. The global power and development potential is now more dispersed and is shifting to the East, primarily to the Asia-Pacific region’ (FPCRF, 2013). And after the intervention in Syria: ‘The world is currently going through fundamental changes related to the emergence of a multipolar international system’ (FPCRF, 2016).

Russia's attempts to alter the status quo have directly affected the hierarchy of prestige in two different ways: first by challenging the American monopoly in the war on terrorism and forcing the USA to recognize the existence of a new multilateral international forum in which Russia can play a key part; and second by strengthening the Russian vision of the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries. Even though the need to obtain acknowledgement of its changed international prestige with respect to the decade immediately after the Cold War has always been a crucial part of Putin's vision, as stated above, if we are to understand the evolution of Russia's foreign policy all the way up to the present attempt to counterbalance the USA in the Middle East, it is necessary to take into consideration the national and regional context forming the political and strategic background to Russian intervention in Syria. The pro-Soviet position of Syria during the Cold War and Russia's previous attempts to avoid tensions that could threaten its primacy and security within its regional area and along its borders are some of the basic reasons for Putin's decision to send Russian aircraft in support of the Syrian regime in the autumn of 2015. Russia was concerned primarily to avoid a political change capable of leading to the possible disintegration of Syria as an independent, multiconfessional, and multiethnic sovereign state (Barnes-Dacey and Levy, Reference Barnes-Dacey and Levy2013). The risk of the repetition of situations similar to those in Iraq and Libya, and moreover in the area of the northern Caucasus, has been repeatedly pointed out in the official statements made to the international press by Putin and the Foreign Minister since 2013: ‘We have a large Muslim population, which is a part of Russia, and has always lived in the territory of our country. Internal contradictions within Islam negatively affect the Islamic community in any country of the world’ (S. Lavrov, 18 November 2013, ‘Nezavisimaya gazeta’, http://www.mid.ru>asset_publiher>content. Accessed 23 June 2017). ‘Our task is exclusively to stabilise the legitimate government and create conditions for finding a political solution’ (V. Putin, 12 October 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk>worldnews>VladimirPutin. Accessed 23 June 2017).

On the basis of these premises, in order to understand the transition from the regional to the global level completely, it is necessary to connect the dimension of the intervention to the objectives.

Objectives

Russia's military escalation from the regional to the global level is primarily strategic in nature: the possible fragmentation of Syria and the risk for Russia of it becoming a breeding ground for terrorist groups would reopen a dangerous internal front that Putin had endeavoured to close by force (Hill, Reference Hill2013). The repercussions of the Syrian crisis could in fact compromise the attempts at forced pacification undertaken in the area of the Caucasus from Abkhazia to Ossetia and Chechnya, thus offering new opportunities both to Georgia and to the Chechen guerrillas. In this situation, Moscow's paramount objective is to maintain the regional status quo established through the previous military operations and prevent an international conflict like the one in Syria from disrupting the balance and allowing radical Muslim factions to expand their areas of influence.

For Russia, the stabilization and control of the Caucasus have represented two fundamental pillars not only for the continuity of ‘exchanges’ with Syria and Iran – through Russian access to the port of Tartus or protection of the Orthodox minority resident in Syria – but also and above all with a view to regaining a privileged position in the Middle East, where Russia lost its influence at the end of the Cold War. Russia's attempt to implement a policy of balancing the United States involves above all the readiness, already shown in Georgia and Ukraine, and now finally in Syria, to use whatever means are available in order to achieve the objectives of its foreign policy. Taking advantage of American hesitation and uncertainty, Moscow told the rest of the world that it intended to play an active part in handling the crises in the Middle East and North Africa, and that it possessed the military resources to do so. At least – and so far only – in terms of intentions, the connection between territorial claims in the Middle East (in terms of expanding its area of influence) and the desire to alter the balance of power at the global level in its own favour could not be more explicit. In Syria, Russia has demonstrated the true nature of its demands. In particular, as pointed out by Dmitri Trenin, Russia has confirmed the importance of military force in the international balance of power. By sending several dozen aircraft to Syria, Putin undermined the monopoly on the global use of force that the USA has held since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Besides asserting its prestige as a great power capable of pursuing its interests through foreign policy at the global level, Russia definitively undermined the US monopoly over the war on terrorism (Trenin, Reference Trenin2016).

Russia's close cooperation with Iran and rapprochement with Turkey and Egypt may continue to redraw the lines of influence not just in Syria but in the region at large, forcing the USA to reengage Moscow more actively in diplomacy. As Krickovic and Weber point out, the ‘grand bargain’ proposed by Russia after its interventions in Crimea and Syria is designed to restrict US power by placing explicit limits on its freedom of action. To this end, Russia is seeking a collective security treaty in Europe that would bind Russia, the United States, and the leading European state and decree the end of American hegemony in Europe and NATO's domination over European security, replacing it with a supranational decision-making body – a Security Council of Europe – including NATO, the EU, and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (Krickovic and Weber, Reference Krickovic and Weber2018).

As regards the Russian vision of the principle of non-interference, it should be noted that both the FPCRF and the statements made by the leaders appear to confirm a strategy aimed at altering Russia's international prestige without changing the rules of the system. The general impression is that Moscow prefers to abide by a rigid interpretation of this principle, according priority to national sovereignty over the responsibility to protect while retaining the right to use this to its own ends whenever its national interests are at stake, as shown by the cases of Georgia and Ukraine. Allison, for example, has highlighted the basic contradiction characterizing Russian foreign policy all the way from the intervention in Georgia to the Syrian crisis. On the one hand, Moscow continues to use the language of international law and to affirm its adherence to the principles of the UN Charter as regards respect for national sovereignty and the principle of non-interference in internal affairs; on the other hand, it continues to pursue a realpolitik design in order to expand its territorial sphere at the expense of the sovereignty of neighbouring countries, obtain a privileged position in the Middle East, and prevent any potentially destabilizing attempts to promote democracy outside and inside its national borders (Allison, Reference Allison2017).

As Averre and Davies point out, Russia's explicit challenge to the legitimacy of the western liberal democracies' approaches to the Arab Spring is closely bound up with its interpretation of traditional international law. Its repeated vetoing of draft Security Council resolutions is based on the already adopted resolutions 2042 and 2043, which state that the Syrians themselves must resolve the crisis, that violence by all parties must stop, that an all-inclusive Syrian dialogue must be encouraged by the international community, and that there should be no outside interference (Averre and Davies, Reference Averre and Davies2015). The Russian interpretation of international law opposes the use of force to remove leaders capable of maintaining the stability and integrity of the state in view of the unintended effects that may arise from the removal of such regimes. Russia's attachment to the basic principles of international law – sovereignty, territorial integrity, and non-interference in the internal affairs of states unless authorized by the UN Security Council – is rooted in a powerful conviction that repudiates forced democratization and regime change, which can destabilize states (and expand Western influence all over the world). Moscow's profound discontent with the consequences of the West's interventions in Iraq and Libya on the stability of the international system and its attempts to preserve the legal basis of sovereignty and non-intervention have won diplomatic support from China, India, and other emerging powers of its envisaged polycentric world order (Averre and Davies, Reference Averre and Davies2015; Marten, Reference Marten2015; Cunliffe and Kenkel, Reference Cunliffe and Kenkel2016; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Bravo De Moraes Mendes and Campbell2016).

In conclusion, our empirical analysis has confirmed the presence of three factors, namely the use of force, the global level of action, and the presence of both territorial (control in the Middle East) and political (improvement of power) demands making it possible to classify Russia's military intervention in Syria as radical revisionism. The difference in the projection of these objectives and the transition from the regional level to the global demonstrates progressive escalation in the degree of threat represented by Russia's present claims and suggests the underlying presence of an explicitly revisionist policy.

Conclusions

On the assumptions that changing the status quo is the basic aim of a revisionist strategy (Buzan, Reference Buzan2008) and that acceptance of the risks involved in the use of force is a key factor in distinguishing the different forms of revisionism (Schweller, Reference Schweller2015), this study puts forward a new typology of revisionism. The six types identified are based on three dimensions: the means employed (peaceful/violent), the nature of the objectives (territory/norms/power), and the level of action (regional/global). The introduction of a new typology of revisionism can also stimulate further research on the possible change of goals, means, and level of action of the potential claims of the revisionist powers that have economic and military capabilities to act both regionally and globally to change the status quo (see the case of Russia, China and, according to some scholars, the United States). Further research insights can be derived from the application of normative revisionism to the various empirical cases (see the Arab countries and the developing).

Our empirical analysis, in particular, confirms the importance of the level of action as a new element with respect to previous typologies and makes it possible not only to demonstrate the central part played by the military option in Russian strategy inside and outside the post-Soviet space but also and above all to confirm the escalation of the revisionist objectives pursued both at the regional level with the interventions in Georgia and Ukraine, and at the global level with the intervention in Syria. The respectively nationalist (Georgia and Ukraine) and radical (Syria) nature of the interventions emerges in relation both to the means and the level of action of these interventions, and to the objectives. In Georgia and Ukraine, Russia obtained the control and/or annexation of territories like South Ossetia, Abkhazia, and Crimea, strengthened its position with respect to neighbouring countries, and impeded the expansion of NATO and the EU. In Syria it obtained control of the port of Tartus, ended the American monopoly in the war on terrorism by asserting itself as a strong party to the peace negotiations, challenged American interests in the Middle East by strengthening the Assad regime, and clearly manifested its determination to halt the decline that set in after 1989. The dual nature of Russia's objectives – both territorial (annexation and/or control over certain areas) and political (improvement of power and prestige at the regional and global levels) – characterized the country's revisionist strategy as a whole from August 2008 to March 2016, confirming the importance of the gradual increase in military expenditure and the reforms of the SAP in pursuit of the same.

If the spectre of the ‘end of history' that hovered over the ashes of communism was swept away by Putin at the end of the 1990s and the impact that his long period in power has had on domestic and regional balances is unquestionable, what is instead still in need of discussion is the effect that his plan of radical revisionism has had on the configuration of the international system as a whole. As matters now stand, any talk of American decline at the military level is misleading and empirically incorrect. It is, however, necessary to take the readiness to use military force as our starting point if we are to understand the nature and the consequences of Russian revisionism at the global level. A power in a position of hegemony cannot in fact hesitate to use all of the diplomatic, economic, and military means at its disposal in order to preserve its status and prevent any destabilizing threats from calling it into question. The USA has made systematic use of force since 1989 to preserve its spheres of influence all over the world and eliminate threats (from figures like Milosevic, Saddam Hussein, and Qaddafi) to the stability of the liberal world order on which its indisputable supremacy rested. Where it intervened militarily, with or without a resolution of the UN Security Council, it told the rest of the world that it was the only actor authorized – or rather self-authorized – to intervene in defence, at least formally, of human rights at the expense of national sovereignty.

Russia's revisionism is the child of this strategy. In order to alter the status quo in its favour, Putin has operated on at both the regional and the global levels to oppose American expansion in the post-Soviet space and its version of humanitarian intervention all over the world, not hesitating to use force in order to challenge the United States openly and bend the international rules to Russia's advantage. At the regional level, Georgia and Ukraine have been blocked. Their entry into the EU and NATO will not be possible without Russian consent or the risk of a frontal clash with Moscow.

At the global level, the effects of Russia's strategy will have to be assessed in the medium and long terms. Russia has now revealed its intentions and explicitly threatened the US monopoly in Syria both in words and in deeds. It is clearly not enough for Russia to alter the hierarchy of power. It wants to obtain acknowledgement of its prestige as a great power in both diplomatic and military terms. In other words, Russia wants to play a decision-making part once again in the management of world affairs. It also wants a less centralized system offering the opportunity to regain important margins of power.

What Russia does not want is instead a clash with the United States on an unequal footing. As long as the mechanism of deterrence realistically prevents such a clash, Moscow knows that it can still play an important hand at the international table. Substantial divergences with the United States remain at the global level. Russia has always manifested its opposition to western intervention in Serbia, Kosovo, Iraq, and Libya, its vision of Assad's future is opposed to America's, it opposes the previous US policy of exporting democracy (as in the case of the coloured revolutions), and it has severely criticized America's withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and the Paris Agreement on climate change. If the hypothesis of a common front is struggling to take off, it is also true that the uncertainties of the West have given Putin a free hand. The ability to seize the opportunity offered by the Syrian crisis is the clearest demonstration of the lucidity and rationality that have characterized Russian foreign policy in recent years. The demonstration of an overall design capable of linking all the different phases is probably one of the most important challenges that the United States will have to face.

Today the combination of Europe's divisions and uncertainties, America's discontinuous involvement, and the absence of any rigid hierarchy of priorities in Western foreign policy has offered Russian revisionism a historic opportunity. The Russian leaders have repeatedly expressed their dissatisfaction with the existing US-led international order and until they consider the possession of a sphere of influence in the post-Soviet space essential for national security, as a sign of their country's power and prestige, any further enlargement of NATO and EU will only exacerbate the situation. In this perspective, some scholars argued that the USA and its allies should adopt a more accommodating policy and engage with Moscow. This means, in practice, the recognition of Russia's legitimate interests in its regional area; non-interference in countries that Moscow considers essential to its security (see Ukraine and South Caucasus); the removal of Western economic and diplomatic sanctions. Others scholars, on the contrary, emphasized that Moscow nationalism and territorial expansionism is a real threat to the liberal international order and suggested that USA and EU should resist Russian revisionism through a mix of a containment and rollback. In short, they should reinforce diplomatic efforts to isolate Moscow; impose more severe sanctions; increase NATO military deployments in Eastern Europe and the Baltic states; provide military support to Georgia and Ukraine (Götz, Reference Götz2019).

On this point, the Trump Administration's National Security Strategy (NSS), published in December 2017, has provided a clear answer to Russian revisionism in terms of military spending. The American strategy document stressed the goal to consolidate US global dominance and prevent any potential challenges arising from Russia and China by showing them that the United States have the capabilities and the will to push them back in all areas. In other words, stability and wealth are a corollary of American dominance that the revisionist powers are forced to accept. This strategy, together with the mutual charges of revisionism between Russia and USA and the mutual claims to be a status quo champion, escalated the conflict and renewed a Cold War climate. If Russia and China could gain more foreign support, the ‘America First’ strategy – as some scholars have feared – could become ‘America Alone’, cementing the US hegemony on one side but releasing a potential Sino-Russian alliance on the other.

Nevertheless, the construction of a stable and legitimate international order has certainly always constituted the greatest aspiration of the dominant power: the preservation of unipolarity, with or without the use of force. The changes of the last decade make it impossible to predict with any certainty how long the American hegemony will last and what price the United States will have – or be willing – to pay in order to preserve it. One thing is certain, however. Putin's Russia is not and will not be a simple onlooker while the USA develops its grand strategy.

Author ORCIDs

Barbara Pisciotta, 0000-0001-9408-2315

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Simona Piattoni, Roberto Belloni, and the journal's anonymous referees for their valuable suggestions enabling me to improve my work considerably.

Financial support

This research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp.