Diversity, equity, and inclusion have been widely discussed in archaeology over the past several decades. These studies, reflections, and advocacy efforts have approached many different forms of oppression in archaeology (e.g., sexism, racism, heterosexism, cissexism, ableism, classism), yet the systematic quantitative studies among them tend to focus exclusively on gender issues. The most common method of assessing diversity in archaeology uses the first names of article authors or grant recipients to guess their genders and quantify numbers of men and women whose research is funded or published. Because first names give fewer clues to race and ethnicity—and no hints at all about sexual orientation, socioeconomic class, abilities, or other identities—this approach is limited to gender, and it has not been expanded to conduct multi-issue or intersectional studies. Furthermore, these studies may miscount or exclude archaeologists whose names do not clearly indicate gender, including some transgender archaeologists as well as those with non-English, androgynous, or uncommon names. Quantitative gender equity studies are, consequently, limited in their utility for understanding diversity issues more broadly.

Here, I present an intersectional journal authorship study, in which I used a survey to ask archaeologists for their self-identifications in terms of gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation. By using a survey, I circumvented the problems and limitations of gender-equity studies based on first names, and I am able to present data on the ways that race/ethnicity, gender, and sexuality intersect in archaeological publishing. I demonstrate that although gender equity in the discipline has improved over the past several decades, the influx of women has primarily consisted of straight, white, cisgenderFootnote 1 scholars; furthermore, the more prestigious a journal is, the more dominated by straight, white, cisgender men authors it is likely to be. This suggests that despite increasing numbers of women, people of color, and queer people conducting archaeological work, the power to influence archaeological knowledge production continues to be in the hands of the most privileged (male, cisgender, straight, and/or white) researchers.

Gender Equity Studies in Archaeology

Feminist scholars have critiqued androcentrism and gender inequities in the field since the 1980s (e.g., Bardolph Reference Bardolph2014, Reference Bardolph2018; Bardolph and Vanderwarker Reference Bardolph and Vanderwarker2016; Beaudry and White Reference Beaudry, White and Claassen1994; Claassen Reference Claassen1994, Reference Claassen2000; Conkey Reference Conkey2003; Conkey and Gero Reference Conkey and Gero1997; Conkey and Spector Reference Conkey and Spector1984; Ford Reference Ford, Hundt, Nelson, Nelson and Wylie1994; Ford and Hundt Reference Ford, Hundt, Nelson, Nelson and Wylie1994; Fulkerson and Tushingham Reference Fulkerson and Tushingham2019; Gero Reference Gero1985; Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Mills, Herr, Burkholder, Aiello and Thornton2018; Handly Reference Handly1995; Jalbert Reference Jalbert2019; Nelson Reference Nelson2004, Reference Nelson2015; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Nelson and Wylie1994; Spector Reference Spector1993; Tomášková Reference Tomášková2008; Tushingham et al. Reference Tushingham, Fulkerson and Hill2017; Victor and Beaudry Reference Victor, Beaudry and Claassen1992; Wylie Reference Wylie, Gero and Conkey1991, Reference Wylie1992, Reference Wylie1997). Scholar-activists and the leaders of professional organizations have addressed sexual harassment and assault in archaeology and related disciplines (Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014; Meyers et al. Reference Meyers, Horton, Boudreaux, Carmody, Wright and Dekle2018; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Rutherford, Hinde and Clancy2017), especially in the wake of the recent controversy at the 2019 Society for American Archaeology (SAA) Annual Meeting (Awesome Small Working Group 2019; Flaherty Reference Flaherty2019; Gilman et al. Reference Gilman, Bocinsky, Sebastian and Snow2019; Grens Reference Grens2019; Hays-Gilpin et al. Reference Hays-Gilpin, Thies-Sauder, Jalbert, Heath-Stout and Thakar2019; The Collective Change 2019; Watkins Reference Watkins2019). Antiracist and anticolonial scholar-activists have denounced racism within the discipline (Battle-Baptiste Reference Battle-Baptiste2011; Colwell Reference Colwell2016; Colwell-Chanthaphonh Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh2010; Colwell-Chanthaphonh et al. Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Ferguson, Lippert, McGuire, Nicholas, Watkins and Zimmerman2010; Franklin Reference Franklin1997, Reference Franklin2001; Gosden Reference Gosden2006; Watkins Reference Watkins2002, Reference Watkins2005, Reference Watkins2009) and built thriving communities of archaeologists of color (e.g., Society of Black Archaeologists 2019). Queer approaches to the past (Blackmore Reference Blackmore2011; Dowson Reference Dowson2000; Voss Reference Voss2000, Reference Voss2008a, Reference Voss2008b, Reference Voss2008c; Voss and Casella Reference Voss and Casella2012) have been accompanied by critiques of heterosexism in the discipline and queer community building (Blackmore et al. Reference Blackmore, Drane, Baldwin and Ellis2016; Rutecki and Blackmore Reference Rutecki and Blackmore2016). There are also growing explorations of classism (Heath-Stout and Hannigan Reference Heath-Stout and Hannigan2020; Shott Reference Shott, Muzzatti and Vincent Samarco2006) and ableism (Enabled Archaeology Foundation 2018; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019a; O'Mahony Reference O'Mahony2015) in archaeology. All of these discourses identify the homogeneous demographics of the discipline as problematic both for the well-being and success of marginalized archaeologists and for our understanding of the human past.

Since its beginnings in the mid-1980s, feminist archaeology has followed two distinct yet related trajectories, which Wylie (Reference Wylie1997:81) terms “content critiques” and “equity critiques.” Content critiques explore how androcentrism and sexism shape our views of the human past and seek to create more inclusive visions of past societies, beginning with Conkey and Spector's (Reference Conkey and Spector1984) “Archaeology and the Study of Gender.” A full review of feminist content critiques is beyond the scope of this article. Equity critiques (including this study) evaluate the positions of women archaeologists, with the goal of creating a more inclusive discipline in the present, beginning with Gero's (Reference Gero1985) groundbreaking “Socio-Politics and the Woman-at-Home Ideology.” Gero demonstrated that men dominated American Antiquity publications on Mesoamerican archaeology, National Science Foundation (NSF) Archaeology Division grants, and archaeology dissertations completed, quantitatively revealing the gender inequities in the discipline for the first time. Over the past three and a half decades, equity critiques (including this article) have often followed her logic and methods in order to quantify inequities between men and women in the discipline.

Following Gero, the NSF's Archaeology Program Director, John Yellen (Reference Yellen, Walde and Willows1991), shared data showing that in the 1989 fiscal year, women both submitted fewer proposals (15%) and had lower success rates than men did (21% compared to men's 27%), which led to serious imbalances in who received funding for archaeological research. More recently, members of the SAA's Committee on the Status of Women in Archaeology demonstrated that these imbalances are much smaller now, nearly three decades after Yellen's report, but that senior research grants are still primarily won by men due to much higher submission rates in fiscal years 2004, 2008, and 2013 (Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Mills, Herr, Burkholder, Aiello and Thornton2018).

Gero's metric of article publications has been more commonly used in order to study gender equity issues. Usually, this work has focused on quantifying the publications by men and by women in a variety of journals and over a variety of periods (e.g., Bardolph Reference Bardolph2014, Reference Bardolph2018; Bardolph and Vanderwarker Reference Bardolph and Vanderwarker2016; Beaudry and White Reference Beaudry, White and Claassen1994; Ford Reference Ford and Claassen1994; Ford and Hundt Reference Ford, Hundt, Nelson, Nelson and Wylie1994; Fulkerson and Tushingham Reference Fulkerson and Tushingham2019; Handly Reference Handly1995; Tushingham et al. Reference Tushingham, Fulkerson and Hill2017; Victor and Beaudry Reference Victor, Beaudry and Claassen1992). In some cases, archaeologists have also examined the gendered politics of citation practices (e.g., Beaudry and White Reference Beaudry, White and Claassen1994; Hutson Reference Hutson2002), and some journals have conducted self-studies to examine acceptances and rejections with reference to author gender (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2020; Rautman Reference Rautman2012). The most recent research has shown that domination by men is pervasive in both national and regional American archaeology journals (Bardolph Reference Bardolph2014), although increasing numbers of women present at regional conferences (Bardolph Reference Bardolph2018; Bardolph and Vanderwarker Reference Bardolph and Vanderwarker2016).

Recent studies have also shown gendered inequities between different types of archaeological work. Tushingham and Fulkerson have demonstrated that there is a “peer review gap”—peer-reviewed journals are more dominated by men than conference proceedings and edited volumes (Tushingham et al. Reference Tushingham, Fulkerson and Hill2017). This gap is exacerbated by the fact that women archaeologists are predominantly employed in cultural resource management positions, in which they have less institutional support and pressure to publish in peer-reviewed journals than their colleagues working in higher education do (Fulkerson and Tushingham Reference Fulkerson and Tushingham2019). Consequently, the particular economic structures of archaeological work lead to disproportionate numbers of women producing large amounts of archaeological knowledge that is relegated to reports that are often poorly disseminated. This situation could be interpreted as a manifestation of Gero's (Reference Gero1985) “woman-at-home ideology”—men are disproportionately given the time, resources, and flexibility to disseminate their research widely in peer-reviewed journals while women disproportionately write gray literature, which is less accessible, less commonly cited, and often considered less prestigious in academic circles.

Taken together, this body of literature shows us that archaeological knowledge production and dissemination through peer-reviewed journals is dominated by men and that—despite variation between subfields and between journals—the problem is endemic. All of this work has been essential to understanding sexism in archaeology. Yet, quantitative journal authorship studies have two major limitations. First, studies of equity in archaeology publications and grants focus only on gender, with no reference to other forms of identity and inequality, such as race, sexuality, nationality, (dis)ability, age, or socioeconomic status. By assigning archaeologists to the binary categories of “men” and “women” or to an “other” or “unknown” category, the scholars conducting these analyses overlook the diversity within each of these categories and among the people who exist outside these categories. Furthermore, there is almost no published data on types of diversity beyond gender. This gap seems to exist because it is possible (although problematic) to assign gender based on first names and the use of gendered pronouns in online biographies in a way that is impossible with other axes of oppression. Although gender equity critiques are based in feminist politics and have been essential to feminist activist efforts within the discipline, they are limited by their lack of an intersectional perspective.

“Intersectionality” refers to the ways that identities and systems of oppression do not exist separately from each other. The term was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw (Reference Crenshaw1989, Reference Crenshaw1991), who was building on the work of many women-of-color feminist theorists (e.g., Collins Reference Collins1991; Combahee River Collective Reference Taylor2017; hooks Reference hooks1984; Lorde Reference Lorde1984; Moraga and Anzaldúa Reference Moraga and Anzaldúa2015). Gender and sexism cannot be examined without also examining racism and other interrelated forms of discrimination and oppression, because every person's experience of gender is deeply affected by that individual's race, age, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and other social identities. When scholars study gender without an intersectional lens, we overlook the diversity within categories such as “man” and “woman,” thereby limiting our understanding of gender dynamics, and we often omit the experiences of multiply marginalized people from our studies. By exploring gender inequities yet excluding other interrelated forms of inequity, publications limit their own understanding of patriarchy and overlook racism, heterosexism, and other types of inequality in archaeology.

Intersectionality has become central to feminist theory and research methods in the three decades since the coining of the term (Cho et al. Reference Cho, Crenshaw and McCall2013; Choo and Ferree Reference Choo and Ferree2010; McCall Reference McCall2005), and it has been increasingly taken up by archaeologists studying marginalized people in the past. With some exceptions (e.g., Sterling Reference Sterling2015), intersectional feminist theory is predominantly used in historical archaeology (e.g., Agbe-Davies Reference Agbe-Davies1998, Reference Agbe-Davies2015; Battle-Baptiste Reference Battle-Baptiste2011; Casella and Fowler Reference Casella and Fowler2005; Croucher Reference Croucher, Croucher and Weiss2011, Reference Croucher, Voss and Casella2012, Reference Croucher2015; Flewellen Reference Flewellen2017, Reference Flewellen2018; Franklin Reference Franklin1997, Reference Franklin2001; Franklin and McKee Reference Franklin and McKee2004; Galle and Young Reference Galle and Young2004; Scott Reference Scott1994; Voss Reference Voss2008a, Reference Voss2008b, Reference Voss2008c; Voss and Casella Reference Voss and Casella2012; Wilkie Reference Wilkie2003). These engagements with intersectionality tend to be content critiques, which are focused on seeing intersecting forms of oppression in past societies. Most published equity critiques remain single-issue focused and non-intersectional. Here, I apply intersectional theory to quantitative gender equity studies.

The second limitation of gender equity studies is the theoretical and methodological problem with assigning authors to gender categories without asking them directly how they identify. Most of the early journal-authorship gender equity studies do not explain how they determined the gender identities of authors, but they seem to rely on first names (e.g., Gero Reference Gero1985; Beaudry and White Reference Beaudry, White and Claassen1994; Ford Reference Ford and Claassen1994; Ford and Hundt Reference Ford, Hundt, Nelson, Nelson and Wylie1994; Victor and Beaudry Reference Victor, Beaudry and Claassen1992). Handly (Reference Handly1995:65) explicitly stated that he was using first names to determine gender, supplemented by a questionnaire sent to his departmental colleagues with a list of authors who had androgynous or uncommon names or who published under initials.

In more recent publications, authors have made clear that they used a combination of first names, familiarity with individuals, and pronouns or gender presentation in photographs from department websites (Bardolph Reference Bardolph2014). Bardolph acknowledges the limitations of this approach:

In determining gender representation based on first names, I acknowledge that I am actually identifying the presumed sex of the individuals and not necessarily their genders. It is possible that some individuals may have been incorrectly categorized because their names do not accurately reflect their genders. Moreover, this method acknowledges only two genders. However, I assume that any such cases would be limited and unlikely to affect the overall gendered trends discussed in this paper [Bardolph Reference Bardolph2014:526].

She makes similar statements in her other articles on the subject (Bardolph Reference Bardolph2018:164; Bardolph and Vanderwarker Reference Bardolph and Vanderwarker2016:117). Similarly, Tushingham and Fulkerson describe their processes of assigning gender in detail, acknowledging complications of identifying an archaeologist's gender (Fulkerson and Tushingham Reference Fulkerson and Tushingham2019:Supplemental Text 3; Tushingham et al. Reference Tushingham, Fulkerson and Hill2017). As these authors acknowledge, many first or given names are androgynous, uncommon, or non-English. Many people have gender identities that either do not match the assumptions people make on the basis of their names or do not fit neatly into binary gender categories. Furthermore, the pronouns used on departmental websites may be incorrect, and a scholar's gender presentation in a professional photograph may not fully reflect that person's identities. Although these methods do give a general sense of the gender imbalance in archaeology, they exclude or miscount many people.

I addressed the problems of intersectionality and of accuracy and inclusion in identifying authors’ genders by using a survey, which asked authors to provide their self-identifications along four axes. Surveys have been used by other feminist scholars to gather data on archaeologists’ experiences of sexism and sexual harassment (Bardolph and Vanderwarker Reference Bardolph and Vanderwarker2016; Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014; Jalbert Reference Jalbert2019; Radde Reference Radde2018) but not to determine author gender for the purpose of conducting publication equity studies. By using a survey in this authorship study, I build on previous gender equity studies and provide multifaceted and intersectional data about the identities of journal authors. Although this method has drawbacks—not everyone invited to fill out the survey does so, and there may be response bias—it allows me to investigate forms of diversity beyond gender, include people whose names do not clearly indicate their genders, and see the intersections between multiple types of identity.

Methods

In order to address the problems of identifying gender from first names and the lack of intersectionality in previous gender equity studies, I sent a survey to authors who had published in any of 21 journals over a 10-year period—between 2007 and 2016 (Table 1). The journals were selected because they are widely read by academic archaeologists in the United States and because they cover a wide swath of world archaeology and a variety of subfields. For the four field anthropology journals (American Anthropologist, Annual Review of Anthropology, Current Anthropology, and Journal of Anthropological Research), I only included archaeology-focused articles in the study sample. The archaeology articles from the four field journals are not meant to constitute samples representing the journals, but only their published archaeology content. The time period under consideration was 2007–2016, because that was the 10-year period just before I began disseminating the survey in early 2017.

Table 1. Background Information about Journals Based on Their Websites.

Surveys were sent by e-mail or Academia.edu direct message to all authors whose e-mail addresses could be found, either because they were published as author contact information in the journal or via Google searches. Authors received a recruitment message with a brief description of the project and a link to the survey, which was a Google Form. The survey included five questions: the respondent's name, gender self-identification, race/ethnicity self-identification, sexual orientation self-identification, and nationality. The name and nationality questions provided boxes for open-ended answers, whereas the other three questions had a variety of checkboxes. Respondents could check all boxes that applied or the “other” box, which provided the option for writing in an answer. Although most surveys of this sort do not ask for respondents’ names, I chose to include that question because it allowed me to connect survey responses to particular articles, tracking the demographics of each journal and weighting my data by number of publications. This choice may have lowered my response rate given that some respondents wrote things such as “anonymous” or “ridiculous to ask for names”; others who did not want to share their names may have chosen not to respond at all. In conformity to typical survey methodology, the survey did not include an explanation of the justification for each question, but if I were to ask for names on a future survey, I would consider including this explanation out of respect for potential respondents’ concern about privacy. Despite the unusual request for respondents’ names, this survey was approved by the Boston University Institutional Review Board (protocol #4381X) because names were necessary to connect survey responses to published articles and because of my careful protocols around data security. I also collected some data from obituaries of deceased archaeologists when my web searches for contact information led me to them. For more details on methodology as well as the full text of the recruitment message and survey, see Supplemental Text 1.

There were 7,005 authors whose work was published in at least one of the 21 journals during the period of 2007–2016. Of these, 1,300 could not be found, 60 were found to be deceased, and 5,645 were sent the survey. Of these 5,645, 1,377 responded—a response rate of 24.39% (with a margin of error of 3% for a confidence level of 99%). Of the 1,377 respondents, 52 declined to write their name (instead, they wrote “anonymous” or similar responses in the required “Name” box on the form). These respondents can be included in the statistics about the population of respondents, but because they are anonymous, their answers cannot be used in journal-by-journal analyses or analyses that weight author identities by their number of publications.

Results

Gender Imbalance in Archaeological Publications

In order to compare my data to those of previous gender equity studies, I begin by presenting data on the gender of authors alone. As shown in Table 2, the journals varied by how many people of different genders published in them. Only Archaeologies had more occurrences of publicationFootnote 2 by women than by men. In all other journals, the majority of occurrences were by men—although the American Journal of Archaeology, Historical Archaeology, Journal of Archaeological Research, and Latin American Archaeology approached gender parity (with fewer than 60% by men). American Antiquity, the Annual Review of Anthropology, and Current Anthropology had the most egregiously imbalanced numbers (with more than 70% by men)—although the Annual Review publishes so many fewer articles than the others that comparison is difficult. All journals had extremely low numbers of transgender and genderqueer/genderfluid/gender-nonconforming authors. Historical Archaeology led with five occurrences (3%) of publication by non-cisgender authors. Ten of the 21 journals did not have a single occurrence of publication by a non-cisgender author.

Table 2. Gender Statistics by Journal, in Ascending Order by Percentage of Authorship by Men, Based on Survey Results.

Previous literature on gender equity in archaeology has also discussed several of the journals in my study: American Antiquity, Ancient Mesoamerica, Historical Archaeology, the Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, the Journal of Archaeological Research, the Journal of Field Archaeology, and Latin American Antiquity. In Table 3, I place my own results alongside those from previously published studies. These data are difficult to compare because the methods of the studies differed (see below for further discussion). My numbers only include the approximately one in four authors who responded to the survey, whereas previously published studies that relied on guessing gender by first name allowed for the inclusion of more articles but potentially included mistaken identities, as some recent authors have acknowledged (Bardolph Reference Bardolph2014; Fulkerson and Tushingham Reference Fulkerson and Tushingham2019; Rautman Reference Rautman2012). Most of these studies count only first authors; I have, therefore, calculated the occurrences of first authorship by women and men in order to compare our data (Table 3). The studies also cover different numbers of years, so I have included year data in the tables along with percentages. Please see the original sources for more detail on the methods of each study (Bardolph Reference Bardolph2014; Beaudry and White Reference Beaudry, White and Claassen1994; Fulkerson and Tushingham Reference Fulkerson and Tushingham2019; Gero Reference Gero1985; Hutson Reference Hutson2002; Rautman Reference Rautman2012; Victor and Beaudry Reference Victor, Beaudry and Claassen1992).

Table 3. Survey Results Compared to Previous Gender Equity Studies: Occurrences of First Author Publication by Men and Women in Various Journals.

a Advances in Archaeological Practice was first published in 2013.

b Gero's study only included single-gender articles for American Antiquity, eliminating multiauthored articles of which the authors were both men and women. Hutson's study did the same for American Antiquity and Journal of Field Archaeology, but for Ancient Mesoamerica, he also provided numbers for multigendered articles with men or women first authors.

Intersectional Data

The intersectional view provided by survey data shows that despite these improving gender statistics, archaeology remains dominated by straight, white, cisgender people. The results of this analysis are presented in Figures 1 and 2 and Table 4. In this section, I again count occurrences of publication.Footnote 2 I also present the data with a simplified framework of identities in order to make the results readable.Footnote 3 Although this simplification loses nuance by grouping many diverse identities under umbrella terms such as “non-white” and “non-straight,” it makes the data much more legible.

Figure 1. Occurrences of publication by people with various intersecting identities, by journal.

Figure 2. Occurrences of publication by people with various minority intersecting identities, by journal. This chart is an expansion of the “other identities” bars in Figure 1.

Table 4. Occurrences of Publication by People with Various Intersecting Identities by Journal.

Note: Journals are ordered from smallest percentage of authorship by straight, white, cisgender men (left) to largest percentage (right).

In almost all journals, the majority or plurality of occurrences of publication are by straight, white, cisgender men. The exceptions are Archaeologies and Historical Archaeology, in which the pluralities of occurrences are by straight, white, cisgender women. In all journals, straight, white, cisgender people vastly outnumber all others. In almost all journals, straight, non-white, cisgender men outnumber straight, non-white, cisgender women. The exception, again, is Archaeologies, where women in general outnumber men and where women of color publish more than men of color—although with such a small sample (seven straight, non-white, cisgender men and nine straight, non-white, cisgender women), it is impossible to say whether these numbers are representative of the journal's patterns in general. In many journals, there are more non-straight, white, cisgender women than non-straight, white, cisgender men—with the exceptions of the Journal of Social Archaeology and the American Journal of Archaeology. This was not surprising, as many interviewees in my dissertation work (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019b:Part 3) told me that Classics and Classical archaeology have long been havens for gay men. These interviewees often cited the prevalence of same-sex relationships in Greek history and literature and suggested that, in consequence, Classicists are rarely homophobes, making the discipline safer for gay men at present. The high numbers of straight, white, cisgender men and women publishing in these journals suggest that the increasing numbers of women authors discussed above primarily comprise straight, white, cisgender women.

Demographics and Journal Prestige

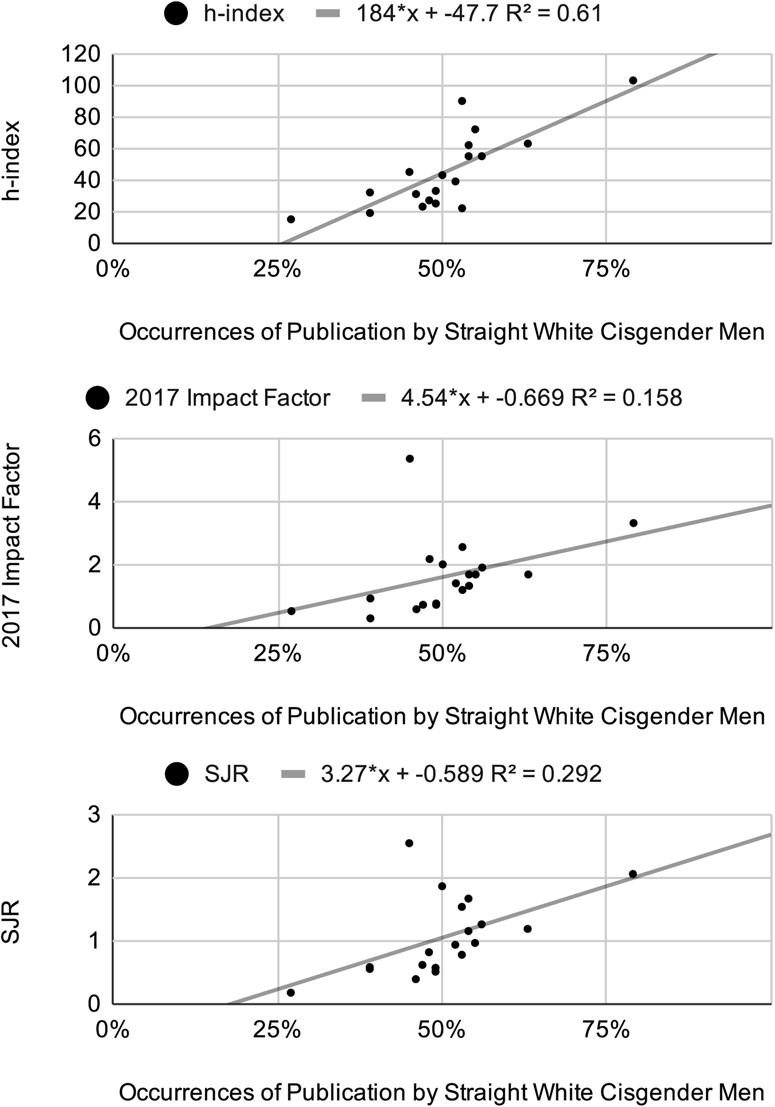

In order to understand the relationship between demographic imbalances of authorship and the prestige of a journal, I analyzed the correlations between percentage of occurrences of authorshipFootnote 2 that were by straight, white, cisgender men and several measures of journal prestige: h-index, impact factor, and SCImago Journal Rank (SJR; Table 5). These three figures for each journal were acquired from the SJR website (https://www.scimagojr.com/index.php). Advances in Archaeological Practice and the International Journal of Historical Archaeology are not included in the SCImago database and are therefore excluded from this analysis.

Table 5. Journal Prestige and Percentage of Authors Who Are Straight, White, Cisgender Men.

The h-index of a journal is the highest possible value of h, for which h articles have been published and each has been cited at least h times in other peer-reviewed articles during the period of study. The h-indices reported in SJR and used in this study are based on the period from 1999 to 2017. This number, consequently, represents a sense of how many influential and often-cited articles have been published in that journal during my study period of 2007–2016 and in the previous eight years. Science has an h-index of 1058, whereas the h-indices of journals in this study were between 15 (Archaeologies) and 103 (Annual Review of Anthropology).

The impact factor of a journal is the average number of citations (in other peer-reviewed publications) per article published over the previous two years. Consequently, this number fluctuates each year and provides a snapshot of the prestige of a journal in a particular short period. Because my sample was articles from 2007 to 2016, I used the 2016 impact factors, representing citations of articles published in 2015 and 2016. Science's impact factor is 41.063, whereas the impact factors of journals in my sample range from 0.52 (Archaeologies) to 3.31 (Annual Review of Anthropology).

The SJR takes into account not only how many times articles have been cited but in which journals they have been cited (Guerrero-Bote and Moya-Anegón Reference Guerrero-Bote and Moya-Anegón2012). A more prestigious citing journal adds to the prestige of the cited journal, and a citation in a thematically related journal is weighted more heavily than a citation in a less-related journal. The SJR metric is also designed to control for the size of journals, given that some journals publish many more articles than others. The 2016 SJR for Science was 13.745, and journals in this study range from 0.174 (Archaeologies) to 2.005 (Annual Review of Anthropology). Like its impact factor, a journal's SJR provides a snapshot of a short period of time, and it changes each year. As a result, I chose to use the 2016 SJRs to measure the prestige of journals at the end of my study period. My sample of articles for which I have author survey responses is too small for a year-by-year study of demographics and fluctuating prestige numbers to be feasible.

Figure 3 shows the h-index, impact factor, and SJR of journals plotted against the percentage of occurrences of authorship in that journal that were by straight, white, cisgender men. Linear regression analysis shows strong correlations between high numbers of privileged authors and each of these metrics for journal prestige (p = 0.00008 for h-index, p = 0.0003 for both impact factor and SJR). In fact, between 56% and 61% of the variance in journal prestige can be explained by their degree of domination by straight, white, cisgender men (R 2 = 0.6123 for h-index, R 2 = 0.5643 for impact factor, R 2 = 0.5757 for SJR). The Annual Review of Anthropology, Current Anthropology, American Antiquity, American Anthropologist, and Antiquity have the five highest h-indices, five of the 11 highest impact factors, and five of the eight highest SJRs. All have straight, white, cisgender men writing more than half of their occurrences of authorship.

Figure 3. Linear regressions of authorship by straight, white, cisgender men and prestige in archaeology journals. All three charts exclude Advances in Archaeological Practice and the International Journal of Historical Archaeology, neither of which is in the SCImago database. Charts B and C exclude one outlier, the Journal of Archaeological Research (45% straight, white, cisgender men; impact factor = 4.000, SJR = 2.543).

Discussion

Demographics and Representation

My study shows higher numbers of women publishing in the discipline than previous studies—even studies of the same publications—did. Of the eight journals that have been previously studied and that are also included in this sample, seven were shown to have more publications by women in my study period than in previous study periods (Table 3). Of the two possible explanations for the difference—response bias and change over time—the latter seems more likely. It is possible that women who received my survey invitation were more likely to fill it out than men were; however, for Advances in Archaeological Practice, my study only showed that 25% of responding first authors were women, whereas Fulkerson and Tushingham (Reference Fulkerson and Tushingham2019) identify 42% of first authors as women for a nearly identical period, which suggests that response bias favoring women is not at play. The discrepancy between Fulkerson and Tushingham's (Reference Fulkerson and Tushingham2019) count of women and my lower number of women respondents for Advances in Archaeological Practice may be an artifact of my small sample size, or it may, in fact, be the result of response bias favoring men! For most journals, my results for the percentage of men first authors versus women first authors are not so radically different from those reported previously that the discrepancy cannot be explained by change over time. In fact, American Antiquity, the most commonly studied journal, shows a clear trajectory toward parity over the past 50 years. Therefore, I argue that archaeological knowledge production is slowly approaching gender parity, with many journals publishing more articles by women over time. Some journals are now nearly equal in numbers of publications by men and by women. One, Archaeologies, was even dominated by women authors (Table 2). Publication statistics for women in archaeology have dramatically improved since Gero's (Reference Gero1985) foundational study. Gero showed that 89% of American Antiquity authors in 1967–1968 were men, and this study showed that only 68% of American Antiquity authors in the 2007–2016 period were men (Table 3).

Because of my intersectional approach and methods, it is clear that the move toward gender parity has not been a substantial move toward diversity in a broader sense, however. Singly marginalized people (e.g., straight, white, cisgender women; non-straight, white, cisgender men; straight, non-white, cisgender men) have had more success than their multiply marginalized peers (e.g., non-straight women of any race/ethnicity; non-white women of any sexual orientation; non-straight, non-white people of any gender), and archaeological knowledge production remains dominated by straight, white, cisgender people (Table 4; Figures 1 and 2). By studying authorship demographics intersectionally, the study demonstrates that not all women have been equitably included in the shift toward gender parity, and it gives a more complete and more nuanced picture of the diversity problem in archaeology.

With regard to binary gender identities, it seems clear that equitable representation would mean approximate equality between men and women: for race/ethnicity and sexual orientation, the goal is not so obvious. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2018), non-Hispanic white people make up approximately 60% of the country's population. In my study, 87.2% of respondents identified as white, suggesting severe overrepresentation compared to the U.S. population. Sexual orientation is even more complicated to judge because the U.S. Census does not ask about sexual orientation. Although there were plans to add a question about LGBT identity to the 2020 Census, this plan was quashed by the Trump administration (Wang Reference Wang2018), so there is no authoritative data about what percentage of the U.S. population is straight. Gallup reported that 95.5% of U.S. adults identified as straight and 4.5% identified as “lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender” in 2017—the highest numbers that they had found—with a continuing upward trend, especially among younger people (Newport Reference Newport2018). If this number is correct, then non-straight people may be overrepresented among archaeologists, as compared to the U.S. population at large. But if the numbers of non-straight people in archaeology do not grow as they do in the general population, that may not continue to be true. Furthermore, the international nature of these journals makes it complicated to use U.S. demographics as a baseline to determine ideal representation. Global population statistics, however, are not a reasonable baseline either. Radde's (Reference Radde2018:233) survey of Society for California Archaeology members about sexual harassment found that 89.4% of respondents identified as heterosexual, a slightly lower percentage than in my study (93.3% of respondents were heterosexual). Unlike the goal of parity between men and women, the ideals we should be reaching for in terms of sexual orientation and race/ethnicity are not clear.

Demographics and Prestige

By examining journal prestige, I show that there are troublingly strong correlations between various prestige metrics and the overrepresentation of straight, white, cisgender men in journals (Table 5; Figure 3). These correlations show that although women and other marginalized people have made inroads into the discipline and produce increasing amounts of archaeological knowledge, the most widely read, commonly cited, and prestigious venues for disseminating that knowledge remain dominated by the most privileged scholars. Archaeology may be becoming more multivocal, but some voices are given more attention than others, as Fulkerson and Tushingham (Reference Fulkerson and Tushingham2019) also found in their study of the peer review gap.

All three of the prestige metrics presented here use citations as a measure of importance in the field, yet the number of citations an article has received is not necessarily a measure of either the number of people reading it or its importance. As both Beaudry and White (Reference Beaudry, White and Claassen1994) and Hutson (Reference Hutson2002) have proved, women are undercited in archaeological literature given their rates of publication. This may also be true of people of color and queer people. To my knowledge, no citation studies have been conducted about race/ethnicity or sexual orientation in archaeology, although an author's race seems to be a minor predictor of citations in the sciences more broadly (Tahamtan et al. Reference Tahamtan, Afshar and Ahamdzadeh2016). A journal that publishes more articles by privileged people might be cited more often because its articles are by privileged people, thereby inflating its h-index, impact factor, and SJR.

The Journal of Archaeological Research (JArR) was an informative outlier in the analyses of impact factor and SJR: it had an impact factor of 4.000 and an SJR of 2.543, whereas only 45% of its occurrences of publication were by straight, white, cisgender men. How does such a prestigious journal maintain such relatively diverse authorship? Coeditor Gary Feinman noted that JArR solicits most of its articles rather than waiting for authors to submit unsolicited manuscripts. He adds:

We do make a concerted effort to solicit both male and female authors, who are doing research that fits our mission. By asking scholars, a good number [of] whom are early-to-mid career to prepare papers on topics relevant to the journal's mission, we may be giving these scholars the impetus, confidence, assurances that they need to submit manuscripts.

He also explained that most reviewed articles are not rejected outright. Authors receive clear revision instructions and reminders to resubmit, leading to a high publication rate for manuscripts that are submitted and reviewed (Gary Feinman, personal communication 2018). These practices likely contribute to the JArR's relatively high numbers of articles by archaeologists who are not straight, white, cisgender men. This model of soliciting manuscripts is most suited to journals like JArR, which focuses on review articles from leading scholars. Annual Review of Anthropology, the other journal in my sample that solicits review articles from leaders in the field, was one of the least diverse journals. This is in strong contrast to JArR, which suggests that Feinman's conscientious efforts toward gender parity make an important difference. His insights do not apply to most journals, which rightfully continue to accept unsolicited submissions, allowing young and unknown researchers to publish their work.

The JArR outlier is informative because the editors’ practice of soliciting manuscripts with an eye toward diversity connects to the small body of literature on the reasons behind gender inequities in archaeological publications. Rautman (Reference Rautman2012) demonstrated that in 2009–2010, American Antiquity published more articles by men than by women because it received more submissions by men than by women. She could find no evidence of sexism in the peer review and editorial processes, and Gamble (Reference Gamble2020) found that the same was true for the calendar years of 2018 and 2019. My study of submissions and peer review outcomes at the Journal of Field Archaeology (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2020) showed that, in recent years, although women have had slightly higher acceptance rates than men, the journal continues to publish more articles by men than by women because men submit so many more manuscripts. Similarly, Bardolph and Vanderwarker's (Reference Bardolph and Vanderwarker2016) survey of members of the Southeastern Archaeology Conference found that men submitted more manuscripts to journals than women did. It remains unclear why this is the case and whether there are similar trends related to race/ethnicity and sexual orientation. One contributing force is the underrepresentation of women in research positions at universities, as discussed by Goldstein and colleagues (Reference Goldstein, Mills, Herr, Burkholder, Aiello and Thornton2018) in their study of NSF grants and gender. However, the JArR example suggests that when women are explicitly given the invitation and opportunity to publish, journal publishing is more equitable.

Perhaps there is a positive feedback loop at play here: more men than women submit to a prestigious journal, so more men than women are published, so the journal is cited more, so the journal is perceived as more prestigious and raises its metrics, so more men than women submit to it, and so forth. Consequently, it may be that the correlations between prestige and the privilege of authors reflect unequal submissions and discriminatory citation practices more than discriminatory publication practices. More research is needed to fully elucidate the processes by which identities shape authors’ submission patterns and the impact and prestige of their published articles. The discipline will not be truly equitable until knowledge produced by archaeologists who are women, of color, and/or queer is as valued, read, cited, and influential as that produced by scholars who are straight, white, cisgender men.

Conclusion

The data assembled in this study demonstrate that archaeology is, indeed, moving toward gender parity as more women enter the discipline and create archaeological knowledge over time. Yet, the large majority of the women entering the discipline are straight, white, and cisgender, so the shifting gender dynamics do not signal a shift in diversity issues writ large, and the discipline remains dominated by white, straight, and cisgender individuals. Singly marginalized people have more success in the sphere of archaeological publishing than their multiply marginalized colleagues. Furthermore, the most prestigious venues for the dissemination of archaeological knowledge remain the least diverse, which shows that although marginalized people are conducting research, they have not yet penetrated the highest levels of the prestige system of academic publishing in large numbers. Peer-reviewed publications—especially those in the most prestigious and oft-cited journals—are essential for hiring, tenure, and promotion decisions in academia, as well as funding decisions at many granting agencies. Although marginalized people are creating archaeological knowledge, those who publish in high-ranking journals are likely to be rewarded with jobs at prestigious universities, funding, opportunities for future research, and leadership positions in the discipline. This trend suggests that the discipline's non-diverse demographics are continuing to reproduce themselves over time.

These insights are possible because of the methodological advance of using a survey to gather data about journal author identities. The survey allowed me to ensure that my data indeed matched the identities of authors and to collect data about multiple types of identity, avoiding the problems of identifying gender based on first names.

There are various ways that concerned scholars can contribute to diversifying knowledge production practices. Marginalized archaeologists can submit their work to more prestigious journals, since discrepancies in publication rates seem to relate more to differential submission rates than to inequitable acceptance rates (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2020; Rautman Reference Rautman2012). Their privileged colleagues and mentors can support them in these attempts by encouraging them to submit to prestigious venues and by offering help in editing and polishing manuscripts. Indeed, my qualitative interview study (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019b) suggested that mentorship is essential to the success of marginalized archaeologists, and this mentorship need not necessarily come from those who share the mentee's marginalized identity. It is also possible for journals that publish work by many marginalized authors to become more prestigious. Because prestige metrics are based on citations, all authors can shape these metrics through their own citation practices. Journal editors and members of editorial boards can solicit articles from talented scholars with an eye toward diversity, as the Journal of Archaeological Research does.

Although archaeologists may not be diverse, the past peoples we study are. In order to understand their experiences, we need archaeologists who hold many different identities and who are working from many different social standpoints. We have to create our knowledge in diverse and multivocal communities in order to rigorously understand the human past. There is still much work to be done to build a diverse, inclusive, ethical, and rigorous discipline of archaeology.

Acknowledgments

This study was first presented as chapters 5 and 6 of my dissertation (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019b), which was defended in the Boston University Department of Anthropology in June 2019. The project was approved by the Boston University Institutional Review Board (Protocol #4381X). Thank you to my dissertation committee members—David Carballo, Mary Beaudry, Catherine Connell, and Chris Schmitt—for supporting and challenging me through this process. As I completed my dissertation, I worked as an editorial assistant at the Journal of Field Archaeology, and I appreciate the support of Editor-in-Chief Christina Luke and my other coworkers. I also wish to thank Jeffrey Fleisher, David Carballo, Mary Clarke, Catherine Scott, and Natalie Sussman for reading and commenting on this manuscript as I developed it into an article. Thank you to Julian K. Jarboe for their help writing a definition of “cisgender” that is accurate, nuanced, and concise, as well as to Víctor Giménez Aliaga for helping me translate my abstract into Spanish. Finally, I am grateful to the 1,377 archaeologists who responded to my survey.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this paper are not available in order to protect the privacy of survey respondents, as required by the Boston University Institutional Review Board (Protocol #4381X).

Supplemental Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2020.28

Supplemental Text 1. Methodological Details of the Recruitment and Survey.