Introduction

In a recent issue of Law and History Review, several scholars explained their extensive efforts to use computational and digital mechanisms to explore the legal archives in more fruitful and creative ways.Footnote 1 Taking cues from these contributions on Anglo-American legal history, this article explores how Muslim jurists have been using new media in Islamic discourses on legal texts. This article is not a survey of digital Islamic legal history or historiography. Rather, it analyzes the internal dynamics of online Islamic legal discourses embedded in their offline and multimedia contexts, where both make use of a rich repository of legal texts composed over a period of approximately 1,000 years. As Islamic jurists discuss these texts through digital and social media, they advance a long textual tradition through hypertext commentaries and supercommentaries.

The rise of the Internet and other information and communication technologies has reinvigorated the spread of old Islamic texts and ideas. These premodern texts are a substantial repository for the sustenance of contemporary ʿulamāʾ in multimedia and cyber platforms. As they produce commentaries and discourses, Islamic jurists breathe new life into the old texts, and the textual past has been extensively useful for them to engage with their audience more effectively and efficiently. This article explores both the archival past and the present mode of circulation. It asks how new media circulate new meanings and interpretations of premodern texts; and how this circulation changes the trajectory of a textual genealogy that goes back almost a millennium. Why does the premodern textual depository matter in the age of e-ijtihad, and to whom does it matter?

I address these questions by looking at the circulation of one text of the Shāfiʿī school of Islamic law, the Minhāj al-ṭālibīn of Yaḥyā bin Sharaf al-Nawawī, and two related texts, its commentary Tuḥfat al-muḥtāj of Ibn Ḥajar al-Haytamī and its indirect summary Fatḥ al-muʿīn of al-Malaybārī. I explore how social and new media circulate these interconnected texts through commentaries, supercommentaries, abridgments, and translations in a number of different textual and hyperextual adaptations. These texts thus simultaneously extend and disrupt the long textual genealogy of Islamic law. In order to examine how the new-media lives of these texts create ruptures in the textual longue-durée of Islamic law in general and the Shāfiʿī legal school in particular, I have conducted the research by employing various interdisciplinary methods of ethnography, Internet studies, and media studies such as multi-sited ethnography, virtual ethnography, online data capture, and digital text analysis. I also conducted fieldwork among the Shāfiʿī communities of Malabar and Madras (India), and Jakarta and Aceh (Indonesia), where I observed discourses and classroom interactions, interviewed teachers, and connected those narratives with related materials circulated virtually on different media platforms. Many of the digital resources are video or audio recordings of offline lectures and debates.

I have explored all the major languages used by the Shāfiʿī Muslim jurists for online and offline legal discussions such as Arabic, Bahasa Indonesia, Malay, Tamil, Urdu, Malayalam, and English, by searching for the texts under focus with keywords in different scripts, spellings, and transliteration patterns. The major methodological challenge was to address many fragmentary sets of commentaries on the texts. For example, some users upload video and sound files of only some lectures, which are often recorded in offline classrooms. For the researcher, this creates a challenge akin to engaging with an incomplete manuscript of the premodern period. A second major problem is the inconsistent transliteration schemes used in different languages to transliterate the Arabic titles of Islamic books, and categorizing the diverse modes of hypertextual engagements into a coherent analytical structure.Footnote 2

In the following pages, I introduce the three legal texts and contextualize them within the long textual genealogy of the Shāfiʿī school. I also describe the ways in which they were circulated in the Islamic world prior to the age of the new media. An understanding of these texts provides a window to the larger commentarial literature that dominated the postclassical Islamic legal tradition and the ways in which they were circulated among Muslim jurists. In the following section, I deal with the historical and historiographical concerns of bringing the Islamic legal textual corpus to new media and Internet studies. Informed by this discussion, the following two sections look into some adaptations of these texts in mass and social media in order to foster understanding of how the circulation of premodern texts advances the textual genealogy.

The Long Genealogy and Circulation of Islamic Legal Texts

In the existing studies on postclassical Islamic law (roughly after 1000 CE), most scholars have explored the Ḥanafī and Mālikī schools but only a few have explored the corpus of the Shāfiʿī school, practiced predominantly in Southeast Asia, in the Indian Ocean rims of South Asia, the Middle East, and East Africa.Footnote 3 The Minhāj al-ṭālibīn (hereafter Minhāj) of Yaḥyā bin Sharaf al-Nawawī (d. 1277) is one of the most important texts, because it canonized the Shāfiʿī school through its prioritization and standardization of the school's opinions covering a vast corpus of texts written four centuries before its lettering. Its methodology and approach provided a framework for later Shāfiʿī jurists to understand and advance the nuances of Islamic law as conceived by the eponymous founder of the school, Muḥammad bin Idrīs al-Shāfiʿī (d. 820). It revolutionized the ways in which the Shāfiʿī law was interpreted, perceived, and transmitted.

The Minhāj stands at the crossroads of Shāfiʿī textual tradition. It belongs to a long genealogy that traces its ancestry at least four centuries back, and produced descendants for another seven centuries. Nawawī wrote it as an abridgement of the Muḥarrar by Abū al-Qāsim ʿAbd al-Karīm al-Rāfiʿī (d. 1227), as he thought that many arguments and judgements in it were flawed and contradicted the “authentic” opinions in the school.Footnote 4 The Muḥarrar in turn is an abridgement of the Khulāṣa of Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī (d. 1111), which Ghazālī abridged from his own Wajīz, which is again abridged from his own Wasīṭ, which is again abridged from Basīṭ.Footnote 5 Ghazālī’s first major law book, the Basīṭ, depended on his teacher ʿAbd al-Malik bin ʿAbd Allāh al-Juwaynī (d. 1085), who had written Nihāyat al-maṭlab, a commentary on Mukhtaṣar of Ismāʿīl Yaḥyā al-Muzanī (d. 878). Muzanī’s text is an abridgement of a text by his teacher and founder of the school Muḥammad al-Shāfiʿī called the Umm. The ancestry of the Minhāj thus can be traced to the foundational text of the school, as the chains of teachers and transmission go back to al-Shāfiʿī.Footnote 6

Over several generations, the Minhāj became one of the most widely circulated texts in the Islamic world through multiple commentaries, supercommentaries, abridgements, and translations, which all have been produced up to present times. The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries witnessed an unprecedented surge in the commentaries, and there were several scholars who specialized in the text and wrote more than one commentary.Footnote 7 Here, I focus on Tuḥfat al-muḥtāj (hereafter Tuḥfa) of Ibn Ḥajar al-Haytamī (d. 1561), a widely esteemed commentary among Shāfiʿī jurists. Tuḥfa’s reception and circulation was accompanied by an opposing work, a commentary called Nihāyat al-muḥtāj, written by Haytamī’s colleague in Cairo, Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad al-Ramlī (d. 1596). Until the eighteenth century, the Tuḥfa mostly circulated in the Hijaz, Yemen, and South and Southeast Asia, whereas the Nihāya was used in Egypt and adjacent places.Footnote 8 By the eighteenth century, this divided circulation changed, because of the increasing cross-mobility of scholars. Yet the Tuḥfa remains one of the most widely circulated advanced texts in the Indian Ocean littoral. Over the years, it has attracted approximately forty textual progeny as supercommentaries, summaries, abridgements, and poetic versions. One of its indirect summaries is Fatḥ al-muʿīn (hereafter Fatḥ) written by Zayn al-Dīn al-Malaybārī (d. circa 1583), who reportedly studied with Ibn Ḥajar at Mecca.Footnote 9 This text has also generated several commentaries, translations, and poems in the Indian Ocean littoral. In nineteenth-century Mecca alone it has attracted four commentators, as many as it did later in South and Southeast Asia.

The Minhāj, the Tuḥfa, and the Fatḥ all have played crucial roles in different modes of legalistic formulations among the Shāfiʿī and non-Shāfiʿī Muslim and non-Muslim communities.Footnote 10 Those texts have been travelling across the worlds of the Indian Ocean and the eastern Mediterranean even to the present. But there are copious premodern legal texts that have had similar trajectories. The texts on which I focus belong to only one textual family, whereas there are five more significant families within the Shāfiʿī cosmopolis whose reception has varied depending on time and place. Transregionally, this genealogy is notably accepted and used among Shāfiʿīs from Syria to the Philippines in their religious curricula, juridical discussions, sectarian debates, and everyday practices of piety.

The degree of usage of these three texts has varied according to factors such as language, length, and precision. All three are written in Arabic, yet the language in the Tuḥfa is difficult to follow, even for a specialist. By contrast, the Fatḥ and the Minhāj are easier to understand, and they are precise. Because of these factors, the Tuḥfa has been circulated mostly among advanced scholars and sophisticated audiences, whereas the Fatḥ is used in the intermediate classes of Shāfiʿī law. The usage of the Minhāj on the other hand has been very different: some use it as an introductory text, whereas others use it as an advanced text. All these variations are also reflected in their contemporary usage in the mass and social media from the late twentieth century onwards.

Ḥāshiya, Media and e-Highway: Dis/Connections

Jurists and other thinkers have long discussed the use of technologies in the Islamic world with close attention to avoiding offending religious directives. In the early nineteenth century, many jurists ruled against the use of printing technology to reproduce religious texts.Footnote 11 Eventually, the general juridical attitude became more favorable, and Muslims from all over the world began to utilize the technology to print thousands of Islamic texts of law, theology, mysticism, and polemics. The result was a complex web of Islamic print culture that changed the way Muslims and interested observers discussed the religion.Footnote 12 By the mid-twentieth century, the debates moved onto the uses of the microphone, radio, and then television. Although many jurists categorically opposed their permissibility on various grounds, others issued more favorable judgements on the basis of each medium's objective, contents, and ethics. Yet others strongly supported the use of this technology specifically because it could be used to instruct and maintain an ideal Muslim umma (collective community).Footnote 13 Although debate about these technologies continues to exist among some Shāfiʿī Muslims, many of them started to utilize the promises of mass and social media by the turn of the millennium in order to advance their engagements with a wider audience and to continue existing discursive traditions through new avenues of mass communication. As when Muslims adopted print-media in the late-nineteenth to mid-twentieth century for everyday polemics, now cassettes, television, and social media dominate the Islamic public sphere. This article is concerned with the undertaking of Muslims in the new media and its implications on the long textual tradition of Islamic law.

By comparison, books and newspapers are considered old media. Within the old media, the advent of printing technology enabled a huge leap forward from a preceding era of manuscript culture. The more recent leap has come through further developments in the telecommunication and information superhighway. The term “new media” is generally used to indicate Internet technology, but here I borrow Thomas Hoffmann and Göran Larsson's definition of the new information and communication technologies (ICT). They explain that ICT is a wider term “for any communication device or application, which comprises access, transmission, storage, and manipulation of information” whereas the new ICT “is characterized by a high degree of digitalization as well as convergence of data-, tele-, and mass communication, the latter not necessarily restricted to conventional mass media like TV (stations) or film (industry) but extending into various so-called social media.” This stands in contrast with the classical ICT such as books and newspapers. Accordingly, the new media discussed here include the mass media such as radio and television along with the social media such as the Internet and I analyze the continuities and ruptures in both realms while aggregating the textual longue durée of Islamic law.

With these things in mind, this article involves three fields of study—mass media, the Internet, and hāshiya—and it combines them by looking at the lives of three interconnected premodern texts. In the last two decades, scholars have analyzed the use of mass and new media for missionary and propagative activities by Muslims.Footnote 14 Charles Hirschkind has explained this process through the concept of “ethical soundscape.” Inaya Rakhmani and James Hoesterey have explored televisions’ capacity to mediate between celebrity Islamic teachers and their mass congregation, whereas Jon Anderson has identified the “digital ummah” as a new unifying network for Muslims in the cyber world.Footnote 15 Looking at various realms of mass and social media, these scholars have analyzed the ways in which Islamic scholars and laypersons negotiate with the new possibilities of technology, instead of rejecting them categorically. They utilize the changing tools of mass communication technologies and enlarge their influences on the everyday lives of the believer community. This development mirrors that in other communities, as Heidi Campbell has argued in her comparative study of Christian, Muslim, and Jewish uses of the new media.Footnote 16 For all these religious communities, the negotiation between the past and developed norms has been an inevitable component in their decisions to accept and appropriate, reject and resist, reconstruct and/or adapt new technologies.

The ḥāshiyas or commentaries and supercommentaries on earlier texts were a product of premodern manuscript practices: instead of copying a text word by word, several students and teachers added their explanations to the original text by way of a new commentary and a new copy. Such new texts were again circulated by producing new textual progeny. In the historiography of Islamic law, such texts written after the classical period have been denigrated as mere repetitions of earlier texts without innovations. But, the burgeoning field of hāshiya studies has questioned this notion by highlighting the potential of commentaries as products of a contemporary intellectual engagement.Footnote 17 A major problem with this field is that most scholars argue that the commentarial tradition had diminished or ceased at the advent of print technology.Footnote 18 I argue that the ḥāshiya tradition is still very present and dynamic in the Muslim world, and that printed texts have advanced it through a wider of circulation of the manuscript texts. This in turn has led to further commentaries and transmissions in new formats. Through hypertextual commentaries, such as audio, video, and virtual commentaries, the ḥāshiya tradition has advanced considerably. Ignoring this means stopping at the gate of “modernity's arrival” into the Islamic world, the popularization of print technology in the nineteenth century, and risks overlooking the innovative ways that the “textual community” of Islamic law has continued to grow.

One major challenge in this area is how to bring hāshiya studies into dialogue with Internet studies and mass media studies. The extant literature in the latter two fields has not addressed the long-existing circulatory mechanism in the Islamic intellectual world, especially that of the textual production and dissemination, and the ways in which it influences the cyber engagements of Muslim scholars and students. This has often motivated scholars to ignore a large body of Islamic scholarly work in the mass and new media. In order to understand this trend, we need to enlarge the frameworks of hāshiya studies by taking into consideration the audio, video and hypertextual commentaries as well, not simply understanding ḥāshiyas to become a dead tradition after the advent of the print technology.

The chronological development of new media technologies—radio followed by television, computers, the Internet, smart phones, and other audio-video-textual-cyber gadgets—has seen corresponding adaptations of Islamic legal texts—audio commentaries, video commentaries, and hypertextual commentaries—from the mid-twentieth century to the present. In the following two sections, I explore these developments by differentiating between two major groups of new media: mass media (radio and television) and social media (different digital platforms).

Textbooks of the Mass Media

Radio broadcasting has been a significant medium for popular and scholarly teaching and for circulating these texts, especially in Yemen and Indonesia. Scholars have demonstrated how jurists in both countries used radio for disseminating legal ideas, delivering fatwas, and interacting with the community. Some Muslim jurists such as Muhammad Amīn al-Ḥusaynī (c. 1897–1974) depended on the media to issue fatwas (legal opinions), to incite jihad against the British Empire, and to support Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany in the 1930s and 1940s. From the 1960s onward, Islamic scholars such as Yūsuf al-Qaraḍāwī (b. 1926) used radio to issue fatwas on several issues.Footnote 19 Brinkley Messick argues that the radio-fatwas reasserted the existing religious discourses in Yemen's Muslim communities, in contrast to Daniel Lerner who argued that the mass media promoted a “secular trend.”Footnote 20 Sunarwoto has contextualized the process of seeking and giving fatwas via radio in socioreligious and political situations that result in the production of particular sorts of fatwas in Indonesia.Footnote 21 Both studies emphasize how radio particularly puts Islamic law to the fore for the ethical teaching of its audience in particular and the community in general. Even though both Yemeni and Indonesian contexts are very much a Shāfiʿī legalist sphere in the 1980s and 2010s respectively along with the Zaydī and Salafī thoughts, both authors have not problematized the textual nuances of the school as such.

This leads to questions related to the sources that the Shāfiʿī “radio-muftīs” and radio broadcasters use to pronounce their legalistic judgements. Musa Furber posits that audiences distrusted fatwas issued through the mass media, especially in comparison with fatwas communicated directly by the muftī (legal expert).Footnote 22 The authenticity of the fatwa is then legitimated on the basis of texts that these muftīs cite. The Fatḥ and its commentaries occur as important texts. These are used the most in radios across the Shāfiʿī world in different forms: as the source of fatwas, a text for learning, and a subject of discussion.

But why select the Fath over the other two texts, or over any other texts of the school? The active broadcasting fuqahā (jurists) deliberately choose not to cite complicated legal texts and discussions to ensure transparency and clarity in their rulings. Most of them have backgrounds in Islamic law, with their intensive training having been at traditional educational centers. They are capable of dissevering the complexities of most issues on the basis of advanced texts of the school, such as the Tuḥfa. But they deliberately go for the introductory and intermediate texts of the school to address questions from the audience. In that sense, the Fatḥ and its commentary Iʿāna cogently provide the gist of the issues, and allow the jurists to interpret passages or phrases according to the questions at hand. Furthermore, the fact that the Tuḥfa is not taught widely in the contemporary Shāfiʿī world, as mentioned, restricts the broadcasting fuqahā from straying into the unfamiliar terrains of advanced legalist discourses. They therefore depend on the textbooks such as the Fatḥ and Fatḥ al-qarīb al-mujīb by Muḥammad bin Qāsim al-Ghazzī (d. 1512), or slightly advanced texts such as Kanz al-rāghibīn, widely known in the Shāfiʿī circles as “Maḥallī” after its author Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad bin Aḥmad al-Maḥallī (d. 1459). Both are taught across the Shāfiʿī cosmopolis.Footnote 23 The general popularity of the Fatḥ among those who have an average training in Islamic law also motivates the scholars to refer to this text, which is immediately familiar and accessible. By contrast, the Tuḥfa and the Minhāj are texts familiar only to those who have acquired advanced training in the field. All these components contribute to the reputation of the Fatḥ on the radio.

How does this text function as a source, textbook, and subject? First, it is a referential source. In most radio-fatwas the muftīs do not mention a particular text that they depended on to pronounce the rulings. They make a general statement based on their knowledge of the topic. But it is important to know what sort of texts they have studied. This leads to the usage of particular texts in particular parts of the Shāfiʿī world. In Indonesia and Yemen, where the radio-fatwas are so prevalent, the Fatḥ stands as an immediate source. Some muftīs clearly state their sources in almost all their fatwas, whereas others state them only occasionally. But often, the Fatḥ is a common reference that these fuqahā mention. Here, citing to a source is an attempt to lay claim to authority and authenticity, as in any scholarly engagement. So whereas established muftīs are not concerned about citing sources all the time, the unestablished fuqahā explicate their knowledge of the premodern texts by citing them in the legal opinions they deliver. On the radio, intermediaries between the muftī and mustaftī (the law-seeker), who may also have some background in Islamic sciences, may cite sources based on their textual knowledge.

Apart from the Fatḥ being one of many sources, the most interesting aspect is its usage as a “radio-textbook.” Eminent scholars have taught it on the FM bandwidth in Yemen, Syria, and Indonesia in the recent past. In Yemen, the renowned scholar Ḥabīb ʿUmar bin Ḥafīẓ read the text over the radio for 3 years. He used to read, interpret, and comment on the texts—as he himself explains elsewhere.Footnote 24 In Syria, Shaykh Rushdī al-Qalam's lectures at the Damascus Shuhada Mosque and Shaykh Ḥusayn ʿAbdullah al-ʿAlī at the ʿUthmān Mosque were broadcast.Footnote 25 The Yemeni and Indonesian scholars broadcast their recordings from a studio, but the lectures of the Syrian scholars were broadcast live. Qalam taught several other Shāfiʿī texts at his mosque classes, including the Minhāj, the Tuḥfa, and its commentary by Ibn Qāsim al-ʿIbādī (d. 1586).

In Indonesia, Kyai Haji Abdul Halim Sholeh taught on the FM station SPFM for 3 years, from 2004 to 2007, at a time when FM radio gained in popularity. The classes ended when a commercial corporate company with no interest in religious content acquired SPFM. Unlike his Yemeni and Syrian counterparts, Sholeh also translated the text into Bahasa Indonesia. He began by reading the Arabic text, then dissected the phrases, translated them one by one, gave the meaning of the whole section, and interpreted it on the basis of further material.Footnote 26 Questions from listeners followed via telephone. He was not the only one to do this. Another daʿwah-radio station (dakwah in Bahasa Indonesia, meaning, literally, “propagation”) from Pasuruan (Suara Nabawiy) broadcast a translation and commentary of the Fatḥ by Ahmad bin Nuh al-Haddad on the ritual laws and by Muhibbul Aman Aly on commercial and public laws.Footnote 27

All these presentations of the text count as oral commentaries for distant audiences not in direct contact with instructors, replicating the traditional classrooms in which the text was taught and interpreted. This popularizes not only the individual text, but also Islamic law, and a classical tradition of Islamic learning. Commentaries, once enclosed by space and time, have become unbounded from the confines and norms of the classroom. These “audio-commentaries” (or “audio-translation-commentaries” in Indonesia) are similar to other textual commentary, but give new forms and content to the ḥāshiya tradition in the age of new media.

Similarly to traditional classroom commentaries, which are naturally transient and die in the classroom, most of these audio-commentaries die in the recording studios after the broadcast. Often there is no archive of them for later use for finding the references that were made or for listening again. Both sets of students have to depend on their memories. Only if students or teachers write down or record the radio commentary does it become accessible to a wider audience. Most recordings have been lost, as happened to many old-manuscript- and classroom-commentaries. I asked Kyai Sholeh about his audio-commentaries, and he has no record of any of them. But new technological developments mean that a few audio-commentaries on the Fatḥ, the Minhāj, and the Tuḥfa are available online for wider use, as I will discuss.Footnote 28

Television-based discussions and fatwa-pronunciations resemble those on radio programs. Although the televised discussions appeared later than those on radio, their usage for circulating Islamic legal ideas was simultaneous, starting from the early 1960s with the programs of such renowned scholars as Yūsuf Qaraḍāwī, who heavily depended on the premodern textual corpus of Islamic law in their pronouncements.Footnote 29 Obvious yet major components that distinguish the television programs are the visibility of the muftī, teacher, and host and the setting of a scene with Islamic architectural or artistic motifs, as well as, sometimes, live shots from the classrooms at the mosques or institutions. Such audio-visual-oral commentaries, showing body language, scenic representations, and artistic impressions, are very different from the traditional modes of “writing” a commentary on a text. The embodiment of television commentaries with visual and sonic experiences brings audience closer to the classroom atmosphere better than the sonic exclusivity of the radios. They also perpetuate such embodied commentarial textuality for repeated telecasts through television channels and the Internet.

Two important dimensions of mass media presentations is that radio and television stations demand high investment and are mostly under government control through typical scenarios of the politico-media complex. This means that most of these religious programs are broadcast in Muslim-majority countries. In Muslim-minority countries such as India and Sri Lanka, there is a more restricted use of these texts in mass media, because of the rarity of Islamic radio and television channels. In India, the available Islamic channels in Urdu and English are broadcast either from Pakistan or the United Arab Emirates and are controlled by the Ḥanafī, Shīʿī or Salafī groups.Footnote 30 They hardly promote any Shāfiʿī texts or ideas. In 2012, the Shāfiʿī Muslims of Kerala started an entertainment channel, and it has a short fatwa-session in which the texts occasionally appear as a source of fatwas, although the muftī mostly does not specify his sources or references.Footnote 31 This also can be seen in a similar question–answer session (telephone-in program) of a Tamil Islamic television channel.Footnote 32

Texts Unbound: Social Media

The emergence of the Internet quickly circumscribed the reach of FM radio in the Islamic world. Platforms such as Facebook and instant communication programs now dominate communications. This has also had a profound effect on religious discussion. The premodern texts are gaining attention through the unprecedented circulatory possibilities of texts, images, and sound files for almost no cost. The premodern Islamic texts are digitized, stored, shared, read, heard, translated, transcribed, and transmitted as PDF, OCR, texts, or images through several websites with different software for a large audience for whom many of these possibilities were inaccessible earlier. The Maktaba al-Shāmila is a classic example of innovation. It is a software-cum-website that acts as host to approximately 16,000 Islamic volumes. Through this website alone, a large library suddenly becomes accessible for students and teachers of Islam who might have had only a few hundred books within reach earlier.Footnote 33 The digital democratization of Islamic texts has substantial ramifications for pedagogic, juristic, academic, and discursive culture across the Muslim world that are yet to be explored.

The most significant element is that all these texts are available in PDF as often as needed. It is not just one copy, but multiple editions, edited by different editors and published by different publishers.Footnote 34 Compared with the historical trajectories of the restricted circulations of these texts after their composition in the thirteenth or sixteenth century, this is a remarkable shift toward popularizing them so that anyone with Internet access and knowledge can access the material (see Figure 1). Until the late nineteenth century, these texts were circulated only in manuscripts at high prices. Often the arrival of a manuscript in a region was celebrated and remembered through stories of miracles and veneration, as was reported when the Tuḥfa arrived in Yemen.Footnote 35 The arrival of printing changed this situation to some extent, yet not everyone could afford a printed text. In several pesantrens, pondoks, and madrasas, students borrowed these texts from their seniors who might have finished studying them, and the printed texts were handed over from generation to generation. In addition, the Tuḥfa was printed with its two important supercommentaries, making it altogether a ten volume text. Only few students could afford the entire ten volume set. This situation dramatically changed once it became available in PDF (or similar digital formats) in countries where almost 100% of the population owns a phone with intermittent web access, as in Indonesia and India. The popularity of soft copies of premodern texts is apparent in a number of online classrooms and videos where teachers, scholars, and students depend exclusively on the soft copies on their Kindles, smart phones, notepads, or laptops.

Original manuscripts and unpublished commentaries have now also been digitized.Footnote 36 Only a handful of textual progenies of the three texts under discussion here have been printed, but several rare and unpublished manuscripts are available on the Internet. One good example is the earliest known commentary on the Fatḥ titled Iʿānat al-mustaʿīn, which is not yet published and survives only in manuscript. It has been digitized and made accessible to the public through a website dedicated to Islamic manuscripts.Footnote 37 There are also audio hypertexts in which producers have combined the text and audio along with slides. One good example of such hypertexts is an adaptation of the Minhāj done by one Abū Muḥammad al-Shayẓamī.Footnote 38 The first part of the Minhāj has been viewed by around 5000 people, and it shows its wider reception of the technique among the audience for a pure legal text like this.Footnote 39 The entire Minhāj has been compiled in such hypertexts in forty-six parts and the viewership varies based on the chapters and topics, from hundreds to thousands.

Figure 1. Homepage of chafiiya.blogspot.nl/, a digital library with hundreds of premodern Shāfiʿī texts. It has categorized the scanned PDFs on the basis of the centuries and prominent authors, and provides links to external digital archives where the texts have been uploaded.

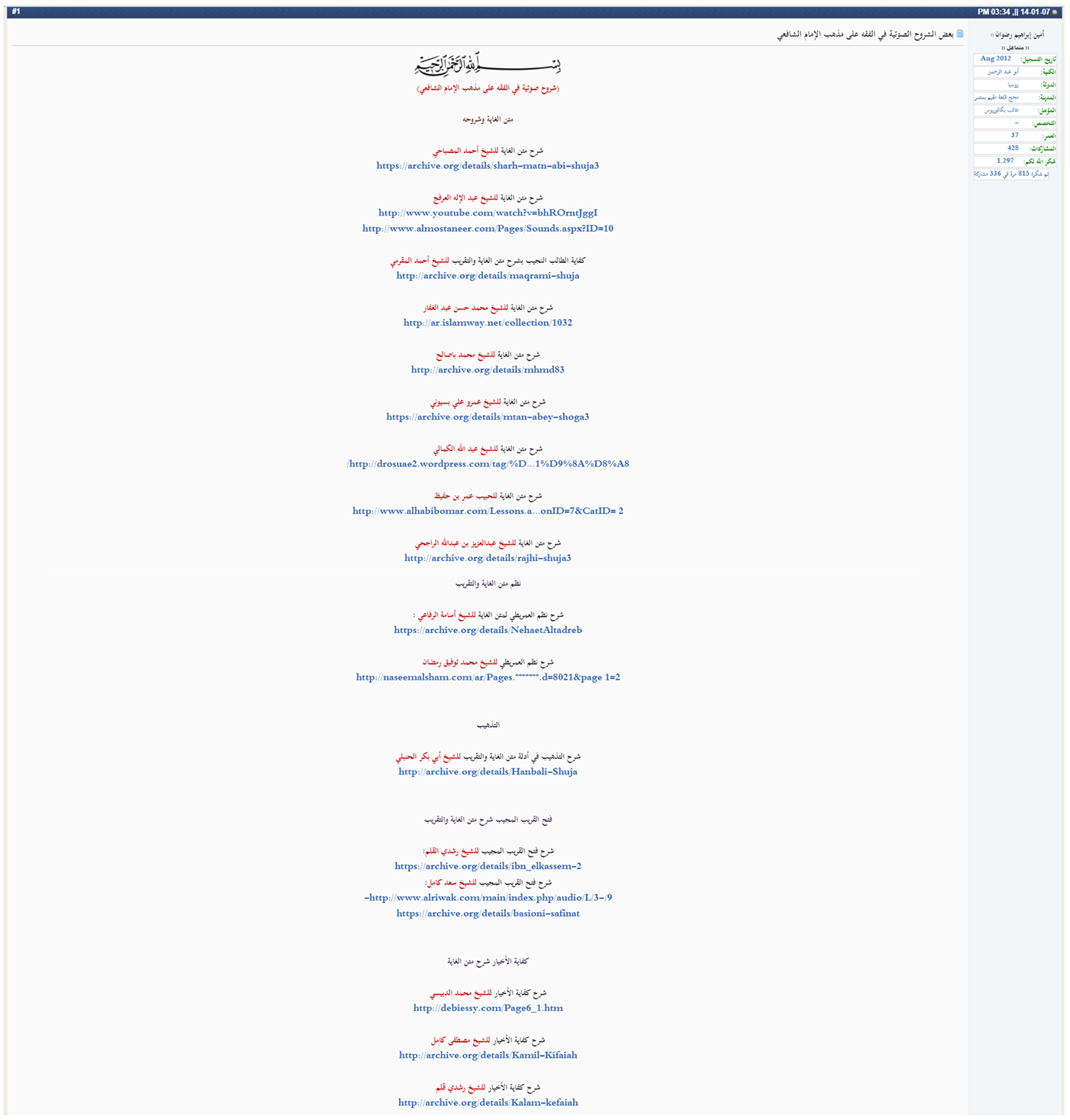

In addition to preserving and disseminating original texts, social media has also been used to preserve and disseminate hypertext commentaries from television and radio channels. As discussed, some oral commentaries from radio broadcasts and classroom instruction were once lost because of a lack of archiving. But now, several such commentaries have been appearing online in archival websites such as archive.org or YouTube through voluntary crowdsourcing, and anyone interested can easily access them. Some such preserved audio commentaries include the commentaries on the Fatḥ by the Syrian scholars Rushdī Qalam and Ḥusayn ʿAbdullah al-ʿAlī and the Indonesian scholar Ḥabīb Aḥmad Nūr al-Ḥaddād.Footnote 40 The recordings of classroom commentaries of the Tuḥfa and the Minhāj also have been uploaded online, similarly to many more audio commentaries of other Shāfiʿī texts.Footnote 41 These are literally called shurūḥ ṣawtiyya or “audio commentaries,” just like any other commentarial genre in the ḥāshiya tradition (Figure 2). Not all these commentaries are complete, however; some have been uploaded online in bits and pieces, but those provide their audience the possibilities and prospects of incomplete manuscripts.

Figure 2. The first part of a long list of “audio commentaries” (shurūḥ ṣawtiyya) for the Shāfiʿī legal texts, as provided on feqhweb.com.

Meanwhile, online radio systems, such as Beyluxe Messenger, and messaging applications, such as WhatsApp, have also helped conserve textual commentaries. Online radios combine older radio channels with the cyber world, in which a new sort of discursive method has evolved around the Islamic law. In such discourses, the Fatḥ again finds a remarkable place compared with the Minhāj, the Tuḥfa, or other commentaries. The online-radios limit access to only those who are registered into particular forums, which are mostly venues of sectarian divisions within the Shāfiʿī communities, as is the case with the forums initiated by the factions of Kerala Shāfiʿīs.

Beyluxe Messenger requires participants to register before using its radio features, but it then allows audience members to interact with broadcasters. Several groups have been utilizing this platform to conduct online classes. A few such examples are on the Fatḥ (organized by the Kerala Islamic Class Room [KICR]), and they were spread over weeks or months. The KICR was organized by the Shāfiʿī Malayali diaspora based in the United Arab Emirates, but it brought together audiences from several countries, regions, and backgrounds, and this would not have been possible for them otherwise. It reflects the “transnational” promise that the Internet provides for its users. Shāfiʿī scholars have used WhatsApp to disseminate recorded commentaries and translations on the school's texts. Unlike in Beyluxe, these classes have less opportunity for audio interaction. In the WhatsApp classes of the Fatḥ, I could access from Kerala and Java; the teachers mostly recorded a summary of the original text's contents in the regional language and they did not read out the Arabic original. This summarized translation of the text defers to the expected concision of the messages on this platform. Some Beyluxe classes have also been recorded and uploaded on YouTube, SoundCloud, and individual websites. Such new digital archives give new life to these online classes and make them accessible to the absentees from the live sessions. The classes available online now are similar to the FM radio recordings, with a few on-screen additions of details of the class, teacher, participants, and notifications about other classes and programs.Footnote 42 The repeated rebirth of such recorded audiovisual commentaries indicate the layered hypertextual longue-durée of the Shāfiʿī texts: the text is first taught and commented on in the normal venue of the teacher; then it is delivered instantly to a new and large audience through appropriate platforms; then again it has another life once it is uploaded in YouTube or other platforms for further access.

The online video channels are also venues for new, non-telecasted, commentaries of the text. This mostly happens with a video recording of a particular teacher's lessons of a particular text at a mosque, home, or educational institution. Here again, the Fatḥ is predominant, with several such classes of commentaries in Arabic, Bahasa Indonesia, Malay, and Malayalam.Footnote 43 In Arabic videos there are only commentaries on the text, whereas in other language videos there are translations-cum-commentaries. The Minhāj and the Tuḥfa are less common in terms of the video-recorded classes available on YouTube, and this may have to do with language, length, and curricula hierarchy in learning and studying this text.Footnote 44 The Fatḥ has an advantage over both these texts in all these respects, although it often has an opposition text. That is another intermediate text entitled Fatḥ al-qarīb, by Muḥammad al-Ghazzī, for which there are also several video commentaries-cum-translations in several languages across the Shāfiʿī world. However, the Minhāj comes next in terms of contemporary popularity, and there are several recently uploaded video recordings of its classes and/or commentaries. Interestingly most of these are from Malaysia, a strong hub of the Shāfiʿī school, followed by Egypt and Indonesia.Footnote 45 In Indonesia, there is a new trend of learning the Minhāj exclusively by dedicating several years to the text through different pedagogic methods. New video recordings also appear to follow global trends, as one reporter observed on the graduation of Minhāj-students in Yogyakarta: “If our teacher says the Fatḥ al-muʿīn is the standard [text] of the national Kiai, well the Minhāj is the standard [text] of international scholars (Kalau guru kami mengatakan fathul muin itu standar kiai nasional, nah minhaj itu standar ulama international).”Footnote 46 On a related note, most of these recordings available online do not represent the canon. For example, there are approximately thirty sessions of sixty classes of al-Saman on the Fatḥ, whereas there are only three incomplete videos of al-Khaṭīb's class on the Minhāj.Footnote 47

Online video-forums such as YouTube provide opportunities to rebroadcast many older television programs on the texts. But there are also teachers who exclusively teach in order to be recorded and uploaded online, without necessarily addressing an immediate audience in front of them online or offline.Footnote 48 Their initiative points to a consumer demand for their classes. In such classes there are all sorts of texts being taught, from the Fatḥ to the Tuḥfa. However, none of these classes are complete. This would suggest that perhaps the consumer demand is not as pervasive as one might think.

As is clear from the previous discussion, the Tuḥfa plays hardly any role in terms of its audio and video representations. This may be because it is impossible to comprehend it in a simple series of lectures or classes. For example, one scholar who has attempted to record video commentaries on the Tuḥfa for an exclusive online audience did not succeed in completing it. On the other hand, the Tuḥfa (and by extension the Minhāj and its other commentaries) proves to be crucial in online forums and discourses. Websites such as feqhweb.com and shafiifiqh.com—along with several Malay, Indonesian, Arabic, and a few English websites—have facilitated transnational platforms for both followers and researchers of Shāfiʿīsm, in which the Tuḥfa and the Minhāj hold an indisputably important position. The appearance of many online-muftīs through many such websites has rejuvenated textual legalistic engagements, especially if those muftīs are trained in traditional scholarly settings. In a recent article, Fachrizal Halim has demonstrated quite convincingly how virtual venues such as shafiifiqh.com and the online institution Shāfiʿī Institute have created a “new legal territory” in the global cyber-Islamic environment, and to what extent the Internet becomes an effective tool for expanding the presence of the Shāfiʿī school.Footnote 49 As those are independent of any state agencies, he concludes: “By maintaining loyalty to the madhhab, the Shāfiʿī Institute may be regarded as a moral movement of the first order whose aim is to create a community of believers who are responsive to the realities of the global world, free of any attachment to the machinery of the modern state.”Footnote 50 Through this they constitute and continue “the fuqahā-estate” of the premodern Islamic cosmopolis in which the fuqahā asserted their autonomy and independence from the state and laity. Here the fuqahā extend this phenomenon to the virtual world that mostly functions across the borders and influences of nation-states.

Before the advent of online legal territories, an adherent always had to follow the ruling provided by a faqīh in his or her town. It was laborious to explore alternatives.Footnote 51 The promises of the Internet thus have been producing “postmodern micro-mujtahids” and a version of “Muslim legal pluralism.” One scholar stated: “By surfing on the inter-madhhab-net, Muslims have successfully responded to the changing social and cultural contexts and have found solutions within Islam without abandoning their Muslim identity and law.”Footnote 52 From a consumer's point of view, all the online fatwas provide adherents with certainty of being correct in matters of religious doctrine while also appreciating the differences between the legal schools, ideas, and texts. But for the muftīs, this is not the case. Many of them strictly follow the parameters of juridical requirements within particular schools.

The role of the Shāfiʿī textual corpus in such virtual venues is not different from the shibboleth of referring back to the accepted texts of the school such as the Tuḥfa and its progeny. Although many online muftīs do not specify the sources of their legal opinions, some cyber platforms and individual e-muftīs always make an effort to cite their sources in a traditional way. The Shāfiʿī websites such as shafiifiqh.com in English and islamonweb.net in Malayalam refer to the Tuḥfa or its ḥāshiyas for numerous legal clarifications. They also draw upon other texts of the school in particular and the Islamic textual tradition in general.Footnote 53 They identify the Tuḥfa as “one of the primary reference works for fatwa in the madhhab,” and al-Ramlī’s Nihāya is the only other text they identified like this.Footnote 54

To give one example of their dependence on the Tuḥfa and its ḥāshiyas, one user from the United Kingdom once asked the legal opinion of the e-muftī on the dress code in a non-Arab country. The questioner specifically seeks for an “Islamic verdict according to the Shāfiʿī [school] and in fact any of the schools of thought” and if there are “any text or rulings” on the issue.Footnote 55 In the answer, the e-muftī recommends the clothes that the Prophet wore and liked as described in “the books of fiqh and also in hadith books like Imam Tirmidhi's Shama'il.” In the following lines, he says that there is no problem with dressing in clothing specific to one's people as long as the clothing does not violate any rulings of Islamic law. In support of this, he provides an anecdote from a Shāfiʿī text (“al-Hawi lil-Fatawi 1/83”) of Imam Suyūṭī (d. 1505) in which this premodern jurist justified wearing local dress, instead of the Arab dress. The fatwa concludes with a note: “This is also related in Ibn Qasim's hawashy on Tuhfah 3/33. And Allah knows best.”

The format of this fatwa confirms the manner in which contemporary followers and scholars of Shāfiʿīsm incorporate themselves into its textual traditions. Although the questioner seeks any text that justifies his/her concern, the muftī comes up with a number of textual references from Islamic tradition and a story connected to one of the towering figures of the school. This story is further legitimized in a legalistic frame by mentioning that it has been related in Ibn Qāsim's commentary on the Tuḥfa. Despite many scholarly and reformative arguments about the Islamic legal schools having lost their currency in the contemporary world, attempts such as this from its followers illustrate how not only the school, but also its entire textual corpus continues to be appealing to the followers.

Furthermore, some of the questions demonstrate the depth of questioners' knowledge in the Shāfiʿī textual corpus, and the discussions become rather interesting as the respondent makes a comparative textual analysis. To give one example related to the texts under discussion here, one adherent asked the website muftīs: “Dimyāṭī Bakrī mentions a text that says that a person's fingernails, hair and blood return to them in the hereafter, therefore, one should not cut one's nails or cut one's hair in a state of janāba [major ritual impurity] because these body parts will return in the hereafter in janāba. This is mentioned without citing any evidence, is there something authentically established in the hadith for it?”Footnote 56 The scholar mentioned in the question, Dimyāṭī Bakrī (d. 1893), is a nineteenth-century commentator on the Fatḥ, and his commentary entitled Iʿānat al-ṭālibīn is one of the most-circulated commentaries on it across the Indian Ocean littoral.Footnote 57

Because of the familiarity of the questioner with this text, the response calls upon higher and earlier texts, among which three different (super)commentaries of the Minhāj appear. In the first part of the answer, the muftī says: “Abū Bakr Shaṭā al-Dimyāṭī related the mentioned text in Iʿānat al-ṭālibīn. As well, both Ramlī and Khaṭīb related it verbatim from Imam Ghazālī’s Ihyāʾ (Nihāyat al-muḥtāj 1/229; Mughnī al-muḥtāj 1/125).” Both these texts in the parenthesis are commentaries of the Minhāj. In addition, he also brings in a supercommentary, the Ḥāshiyat al-Qalyūbī (a commentary on Maḥallī’s commentary on the Minhāj), which also cites Ghazālī’s statement along with several other legal and extralegal texts.Footnote 58 This elaborate yet intimidating citation of sources is a strategy of the e-muftī to address the user's learned inquiry with regard to the textual corpus.

The Facebook pages and groups dedicated to these texts also merit discussion. They disseminate the text to a larger audience through translation and selective reading along with other religious contents. One good example is the page “Kitab Fathul Mu'in—Arabic” from Indonesia.Footnote 59 Eight years ago, in 2009–10, the page provided translations of the Fatḥ along with the original text, but now it provides all other religious content and hardly touches on the Fatḥ as such. There are also several groups dedicated to various aspects related to the text: from its study circles, to its legal discussions (masāʾil), debates and discussions, and e-learning. The same can be seen for the Minhāj and the Tuḥfa, although their recognition is limited to the Arabic language spheres.

Heidi Campbell has emphasized the connection between online and offline contexts: “offline attitudes and behaviors often inform life online, and vice versa.”Footnote 60 Hypertext commentaries, online classes, and Facebook groups often begin in offline classes in a mosque or madrasa. These materials are posted online not only to attract followers, but also to extend sectarian and doctrinal debates into the digital world, exhibiting the online-offline embeddedness.Footnote 61 As I briefly mentioned about the subscription to online radio, the broadcasters and audience of particular digital platforms and websites are highly divided within the Shāfiʿī community. Questioning Anderson's argument on the ability of the Internet to reunite the ummah in a form of an e-ummah or digital ummah, al-Rawi has argued that the ummah online is not that unified, but rather highly divided.Footnote 62 Following his cue, I would say that if there is an e-Shāfiʿīsm or a digital madhhab that shares the vocabulary and texts of the Shāfiʿī school of law, that very doctrinal community is also highly divided.

One good case that exemplifies this debate about how the Shāfiʿī textual corpus influences new media is a video-clip titled “Alavinta Thuhfa” (the Tuḥfa of Alawi).Footnote 63 This video shows not only offline–online embeddedness but also the multilayered hypermedia that has been enabled through enormous shifts in technology, and its prompt use by the Muslim scholarly communities. In this video of just under 3 minutes, there are two visual segments that represent the functionality of layers of new media in the inter- and intra-sectarian debates of Shāfiʿīs in Kerala. The first segment is a speech by one Shāfiʿī scholar who changed his sectarian and organizational affiliation, who accuses his old sect of fraud and forgery in using Shāfiʿī texts during the intra- and intersectarian debates. His main target is one scholar named Alawi Saqafi. According to the speaker, this Alawi had been ascribing his own statements and arguments to the Tuḥfa and other Shāfiʿī texts during the heated debates with Salafī scholars, under the assumption that the Salafī scholars were not familiar with the Shāfiʿī texts or other rich Islamic textual traditions. Therefore, our speaker states that the scholars in Alawi's own sect would mock Alawi's quotations by saying that those are from “Alawi's Tuḥfa” and are not from Ibn Ḥajar's Tuḥfa. The speaker's grudge against Alawi now is because the latter used this trick against the scholars of the new sect that he has joined. His speech abruptly stops and fades into the second segment of the video. Here a Salafī speaker appears and tells his audience about such forgeries of the Shāfiʿī scholars by showcasing Arabic texts and quotes. He says that they should not be cheated by such kitābs and scholars, and that even if those are true kitābs and quotations, only the Quran and hadiths should be accepted as true evidences.

These two visual segments have been uploaded to YouTube after migrating through five communication channels. The first speaker delivered his speech through a microphone to his seated audience. A recording of this speech was transmitted to a broader audience. A CD of the recording, “To the Signalers of Unity,” was circulated among the new Shāfiʿī sect that he joined and also among his opponents. It also found its way to the Salafī group who found it to be a good example of the Sunni scholars’ forgeries of the premodern texts. Third, the second speaker uses this part of the CD in his speech through an LCD monitor to prove his point, and his speech was also recorded. Fourth, the recorded material along with the LCD clip from the first CD was published by the Salafīs as a new CD. Finally it ends up on YouTube. Although this video has been viewed by only a few hundred people, it is a clear example of how a single performance ends up embedded in the online world after journeying through multilayered techniques and technologies of debates.

It is also apparent in the foregoing example how a particular school and its vast textual body becomes part of, and ultimately extends, a discursive continuum in the long juridical and polemical histories of Islamic law both schematically and schismatically. The premodern texts are the central cord that enables this continuum from the age of manuscripts to the age of algorithms, from street fights in tenth century Khurasan or nineteenth century Cape Town to the cyber-attacks of the twenty-first century.

Conclusion

The dissemination of premodern Islamic legal ideas and texts in cyberspace contributes to the “democratization” of a knowledge-system that was once dominated by the trained fuqahā and affiliated institutional structures. This is a remarkable shift in the circulation of Islamic knowledge that is far more intense than the historical dissemination conducted via translations and the printing of such texts in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Here, I have demonstrated how premodern Shāfiʿī texts become easily accessible to those who would like to consult them via mass and social media, giving followers more opportunities to stand within the ratiocinations of the school and to advance its message to a larger audience.

An overwhelming spread of premodern texts through mass media such as radio and television, social media, and the Internet helps students and scholars of the school to capitalize on the effectiveness and efficiency of new technological developments in order to promote the school among new generations and to enhance their loyalty and affiliation, instead of moving away from its doctrinal frameworks. These media platforms help them to keep the traditional school(maḏhab)-affiliations relevant and perpetual in the new age of democratization of knowledge. In contrast to the audience who has several opportunities to forum-shop in their searches for a greater piety, the providers of the information try to reassert the school's frameworks and verdicts by broadcasting, telecasting, digitizing, citing, and siting its premodern textual corpus. This active media presence, in turn, helps the school continue “to play a role as a source of authoritative doctrine and a proven mode of legal interpretation for Muslims” and “to expand its role beyond territorial and cultural boundaries.”Footnote 64

The “new media ḥāshiyas” are very instrumental in this process. Diverse forms of media engagement with the premodern texts (whether textual, audio, visual, or combined) have produced several unconventional ḥāshiyas, such as audio commentaries, video commentaries, audiovisual commentaries, and hypertext commentaries. They all contribute to the Islamic textual longue-durée, as I demonstrated through the cases of the Minhāj, its commentary the Tuḥfa, and its indirect summary the Fatḥ. This article has only dealt with these three texts of the Shāfiʿī school, but similar cases can be made for other texts within the school and beyond. Ḥāshiya studies should take this new corpus into account, instead of focusing exclusively on the nineteenth century with the advent of printed texts. The ḥāshiyas based on and developed through manuscript-cultures might have declined with the spread of printing technology in the Muslim world, but the practice of producing ḥāshiyas as such has not declined at all. Instead, the new technological promises of sonic, visual, social, and virtual media have advanced it more than ever before. The simple textual tradition, therefore, might have been eroded, but a new hypertextual tradition has emerged to reinforce the centuries-old textual genealogy of Islamic law. These new media ḥāshiyas do not operate in a vacuum of the digital world, but are also a strong exemplification of online–offline embeddedness and a lively mimesis of the premodern commentarial tradition of Islam and its laws.