INTRODUCTION

On 8th June 2018, I presented on the relationship between libraries and work at the annual conference of the British and Irish Association of Law Librarians. This topic was one that stood out for me because, in this digital age, what we consider to be ‘work’ and the way we go about it is changing. As a result of new technologies such as laptops, tablets and mobile phones, we can now work anywhere, anytime. The library is ‘emerging as a new typology of workplace combining concentration and collaboration’.Footnote 1 Libraries in workplaces are also performing a new function: they are no longer simply a destination for book or reference requests; they provide workers with a unique setting within the office for focused study and collaborative work.Footnote 2 This paper provides detailed insight into examples of where the functions of the library and workplace have been combined in cities around the world.

In essence, custodians of the office library have a key role to play in working with office staff to define the form and function of the library so that it is tailored to staff needs. Indeed, customer experience matters now more than ever. Visitors are looking for more than just four walls and a roof. They are looking for an attractive package of additional extras. They assume that super-fast broadband connectivity is a given; they also want a good on-site food and beverage offering; they want a diverse range of different options, such as break out space and collaborative work areas. Therefore, there needs to be a transparent relationship between staff and employees, and a hands-on approach to establishing what people really want and when.

The chief executive officers of the public libraries that I have visited spend a lot of time thinking about the kind of experience they want their customers to have and how they can provide it through the design of their services and spaces. Funded by the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust, over the last three years I have visited more than 50 library buildings on four continents—Europe, North America, Asia and Australia. My aim was to gather knowledge about the vision for public libraries in light of the impact of new technology that challenges the need for physical books yet highlights the continued need for neutral community spaces. In this paper, I focus on three aspects of my research: how the rules of the library are changing, how the services are evolving and how the spaces are designed to accommodate existing and emerging spatial requirements.

HOW THE RULES OF THE LIBRARY ARE CHANGING

Connections

It's not about the books. It's about making space for people. As Karin Latimer writes, the collection is no longer the single most important thing in the library:

The modern university library is all about making connections—connections between different groups of library users, connections between library users and library staff, connections between library users and resources.Footnote 3

As with online retail, where objects can be bought at a distance from a shop, libraries have had to consider themselves more than just a warehouse for storing merchandise. They now provide opportunities for their customers to engage and interact with the collection in interesting and innovative ways. Their collections are also expanding to include more than books. For example, Vancouver Public Library has musical instruments that people can borrow. It also has sound booths where people can record music they have composed. Learning takes on a new meaning when it's about what people learn do to with an object they have borrowed from the library.

The librarians with whom I spoke observed that the people who spend most time in the library need the floor space. For this reason, they are reducing the size of their collections to create more space for people to physically interact and engage with each other, and the collections, in more innovative ways. Smaller branch libraries have resorted to reducing the number of book stacks on the floor; larger university libraries have found high-density storage solutions that enable them to store a significant collection of books on site. James. B. Hunt Jr. Library at North Carolina State University has a ‘bookBot’, which is a robotic book delivery system that can hold up to two million books and requires just one-ninth of the space of conventional shelving, although staff and students interact with it using an interface that replicates the shelf browsing experience.

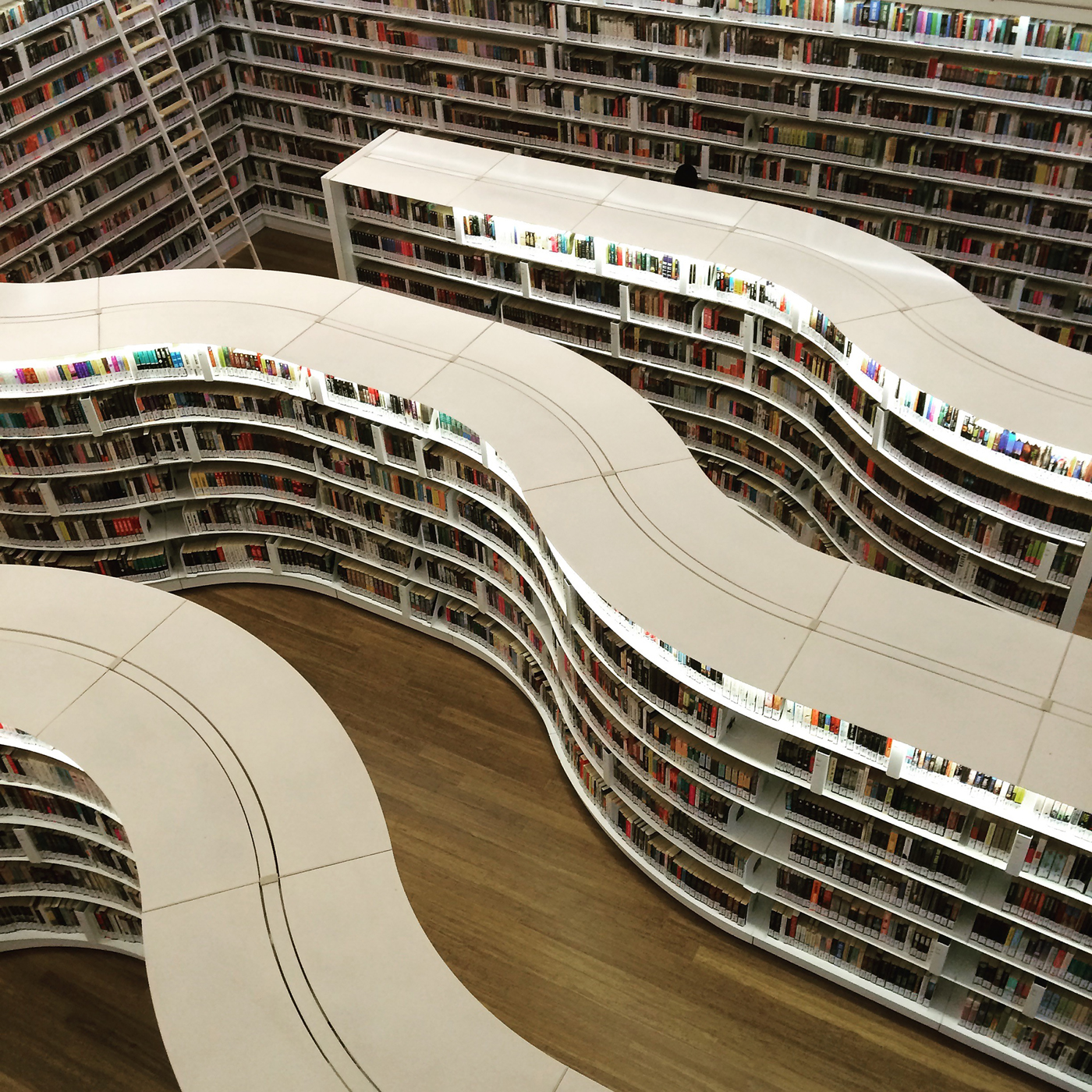

Figure 1. It's no longer about the books.

Ownership

The second cultural change that I want to explore is ‘ownership’. Librarians now encourage customers to play a role in the design and operation of the library. The customer is now the expert. For this reason, it's important to find ways for them to get involved, and there is scope for them to do so. Some of the public libraries I visited have experimented with ‘designing thinking’. For example, Chicago Public Library worked with IDEO, funded by the Gates Foundation, to devise what has become known as the ‘library tool kit’. The tool kit introduces a way of working that helps libraries to understand the needs of their customers and engage with their community. Chicago Library used this methodology to attract ‘millennials’ by considering how playing board games could be approached as an educational process or learning strategy.

In other cases, librarians have involved their customers in the organisation of community activities and events. At Library 10 in Helsinki, for example, patrons have hosted more than 200 events in the library. The regional manager told me, ‘A few years ago, we organised everything, but today customers organise events themselves. 90% of events are organised by customers. They come to music events, workshops. They come here to help and teach each other’. He no longer decides what events and materials the customers need, he lets them decide. In this way, he says that Library 10 is moving from ‘individual library use to collective library use’. However, the librarians I spoke to were concerned with how far they should take this: Should they let customers take over? Should they transfer ownership to their customers? The regional manager concluded: ‘I guess that is what we have to do’.

In the spirit of collaboration, Library 10 staff and customers sit behind smaller and lower desks that have curved ends. Furthermore, they come out from behind their desks to proactively engage with customers on the shop floor. This reduces the emphasis on programming the activities of customers and increases spontaneity. The librarians respond to customer requirements at the moment in which they engage with them. Similarly, in de nieuwe bibliotheek in Almere in the Netherlands, staff are now called ‘hosts’ and greet customers at the library entrance. They proactively engage with them and are taught to anticipate their needs even before they walk through the front door. Likewise, in Calgary librarians have designed customer profiles that help them understand the needs of different customers or user groups.

Personalisation

The expectation and assumption is that customers want to curate their own library experiences. This has led to librarians taking a ‘hands-off’ approach to the delivery of library services, through adopting a new light touch customer engagement strategy or even using a mix of analogue and digital delivery mechanisms.

Libraries are now increasingly designed as an environment in which parents and teachers are expected to take a back seat and let children learn though discovery. The Library Concept Center in Delft includes an art gallery. The resident artists encourage children to play and make sculptural pieces with objects and materials. They can build what they want, depending on their own individual vision. The artists give children new objects and materials to work with in order to surprise them each time they visit. In this way, the Center follows the Reggio Emilia art philosophy, which the policies and projects manager explained to me is ‘a balanced philosophy around creating an environment where children can discover through playing’. It changes every day; it is an evolving maker-space. Children have to leave behind what they make there so it's available to others.

HOW THE SERVICES ARE EVOLVING IN THE 21ST CENTURY

The Library Concept Center has also experimented with digital as well as analogue services. People are connected via mobile devices, and this has an impact on how they use and engage with library services. A good example of this is a Library Concept Center innovation called Tank U—a download station that uses Bluetooth. Tank stations can be placed in different locations outside the library and customers can download installed content from them at any time. People with Bluetooth applications on their cell phones can download content to their phones and play it on the train or wherever they want. The theory is that they will want to visit the physical library once their interest is aroused as result of accessing free content outside the library.

Some remarkable strategies are being implemented in Singapore. The National Library Board is harnessing new technologies to create a more seamless service. It has created a mobile app which customers can use to borrow ebooks, reserve books, pay their fees online, and scan a barcode and borrow a book instantly. Customers can receive book recommendations through the app when the library has new arrivals, and there is a search function that enables customers to review the library's programme of events across the system. The library can also use the app to recommend books that a user might like based on their age and gender (although it does not use their browsing history in order to protect customer privacy).

The Singapore National Library Board has also tapped into the Internet of Things—the interconnection via the internet of computing devices embedded in everyday objects—enabling them to send and receive data. In one of the branch libraries that I visited, they have installed a noise management system. There are microphones in the area that pick up noise, and a light attached to the microphone goes red when the teenagers are being too loud and an announcement is made telling them to be quiet.

Libraries are also remodelling their websites to make them more user-friendly. Indeed, a library is open for certain hours a day, but its website is always available. For example, Chicago Public Library has partnered with BiblioCommons to revamp its website to showcase more events. Staff were looking for a way that would allow them to promote and discover programmes that the customers wanted but didn't know were offered by the library.

HOW THE SPACES ARE DESIGNED TO ACCOMMODATE EXISTING AND EMERGING SPATIAL REQUIREMENTS

The three service design principles are of course reflected in the way that architects are designing library buildings and spaces.

Connected by design

Firstly, they are designing libraries as spaces where the life of the city unfolds. Schmidt Hammer Lassen envisaged Aarhus DOKK1—completed in 2015—as a covered urban square, ‘A place where people meet, a natural point in the city to meet, exchange information, be together’. There have been proposals to ‘re-invent libraries as agoras of the 21st century’ in the belief that ‘libraries can fill the gap between people and politicians’.

Thus, there needs to be space where people can come to spend time together, share ideas and engage with each other. In Calgary's new central library, Snohetta and DIALOG have resolved this need for more space, not by including additional space but by creating adaptable areas. As the deputy CEO explained:

Even the behind the scenes workspace are designed in such a way that they can be transformed into public spaces if we wanted to move all the back of house activities out of the building. So, that was our expansion strategy, rather than build more space that wasn't occupied we decided to design the behind the scenes workspace so they can be vacated.

The carpet colour is the same back and front to indicate a seamless connection between the two. ‘It's a visible manifestation of the idea we had’, the deputy CEO clarified. There are also no load bearing walls in the back of house areas. Librarians have no idea what services and spaces patrons will need in the future, so it is by ensuring a space is adaptable that it will remain socially sustainable.

Figure 2. Library@Orchard in Singapore.

Creating connections by design can be interpreted more broadly than this, however: libraries not only have a role in bringing people together, they are a means of connecting different parts of the city. The libraries I visited in Denmark, Finland and the Netherlands all benefited from their location. Whether they were in a main square, shopping centre or medical centre, they had all been designed to be close to other services in order to attract people who were passing.

De nieuwe bibliotheek in Almere Stad in the Netherlands sits on the main square, where there are shops, cafes and restaurants that draw visitors from all over the town. The new library, designed by Concrete Architectural Associates and completed in 2010, has been designed to shift the flow of people from the old town to the new town. The flooring in the entrance is similar to the material in the main square in order to create a seamless connection between the two spaces. In this way, what happens in the main square influences what happens in the library. For example, Wednesday is market day, which brings more visitors into the building.

In Finland, in Espoo near Helsinki, the regional shopping centres are the areas of most activity. Staff say that a library is a desirable service, and it is beneficial to be located somewhere people are passing by. The library in Sello is the second library in Espoo to be situated in a shopping centre. It is the largest library in the area. Since its opening in 2003, staff say that it has been the most frequented library across the cities of Vantaa, Espoo, Kauniainen and Helsinki-the Helsinki metropolitan area.

Owned by design

Secondly, architects are designing libraries as spaces in which people feel a sense of ownership and belonging. This can simply be achieved by designing the library so that it is ‘as open as possible’. As the deputy chief executive officer of Calgary Public Library explained to me:

People will enter the library via the gentle ramping… and enter into the vestibule. It is important that they can see all of the floors; they cannot see what is on the floors, but they can at least see through them. We expect light to come through this building.

Customers are likely to spend a significant amount of time in the building, so they need to know how it functions. If they can see what is on the fourth floor, they are more likely to be able to figure out where to go for themselves. The openness of the building helps customers who use it to navigate it, so they feel like the ‘place was built for me’. According to the deputy CEO, ‘They feel like they belong here’, and signage is in place simply to nudge them in the right direction: ‘If we have to explain in great detail how the building works [with signs] then we have probably failed’.

Meanwhile, architects and interior designers work to make a public library more ‘welcoming’ by focusing on what librarians call the ‘patron path’, which is the way in which patrons orientate themselves when they enter the library. ‘Don't block it… don't put a load of information in the first few metres of the vestibule because they won't read it,’ stated the chief executive officer of Calgary Public Library.

I noted that many of his suggestions for the new library came from thinking about retail. In retail, ‘merchandise’ is displayed to attract customers into the building. So, for example, his suggestion would be to put the ‘hold’ books at the back of the building, where the bread and eggs would sit in a shop, so that people have to walk through the space to reach them. The idea, of course, is that anyone entering the library to pick up a ‘hold’ book might be tempted to browse all the other books on the shelves on the way.

Lighting also makes a difference. Many of the people I have spoken to have commented on the quality of the lighting in their library. The associate director at James B. Hunt Jr. Library stated that lighting is one of the most important design features to consider in a library. When designing the Hunt Library, he worked with the architects—Snohetta and DEWG—to ensure that the lighting was as effective as possible for the students. Lighting creates atmosphere, so it is a way of providing students with different working environments without changing the tables and chairs. Indeed, Hunt Library has a range of general, task and ambient lighting to create different atmospheres. And, of course, the building was designed to maximise the amount of daylight entering the space that students can enjoy on all floors.

Personalised by design

Thirdly, architects are designing libraries so that they can be adapted to meet the requirements of the end-user.

For example, the new library in Halifax, designed by Schmidt Hammer Lassen and completed in 2014, does not have any walls. According to the lead architect from Fowler Bauld and Mitchell, it has columns so there are no walls that have to be knocked down in the future. The spaces in the new central library were designed for all ages. In other words, while each of the spaces has been clearly defined in such a way that it is usable and efficient, they can be used by anyone. As the youth services manager explained, ‘We are looking at a more dynamic audience—we are looking for the spaces to be used by all ages, teens and adults.’ This means that when teenagers are in school, the spaces will be used by adults. The adult spaces have yet to be used as fluidly as the teen spaces.

The furniture at the library is also mobile, so that staff and visitors can pull the equipment out and push it away with ease. Even the soft seating on the second floor is arranged so that people can sit on it any way they want to. One librarian observed that it has been interesting to see how the customers move the furniture around: ‘There is furniture that you think that visitors would not move… but they do!’

According to a regional manager in Seattle, the most flexible spaces are those that are neutrally decorated: ‘I suggest it is better to stick to the simplest things. For example, a table that is going to be taken over by a high school study group at 4pm needs to be a comfortable reading space for a guy looking at the stock prices in the morning, so the “reversible lane” approach.’

However, older buildings are often difficult to make flexible. For example, the Northeast Branch of the Public Library in Seattle was extended in 2004, and the original building was redesigned in 2013 to create a more flexible environment where children and caregivers can more easily interact. I also visited the Capitol Hill Branch of the Public Library when conducting my Winston Churchill Memorial Trust Fellowship research. The library had replaced its carpet and at the same time reconfigured the area near the entrance. The reference and information desks had also been consolidated into one desk to create more flexibility and increase visibility throughout the space, and all of the fixed shelves in this area had been moved and replaced with much smaller, lower shelves that immediately opened up the space so that the staff could see the patrons and were visible to the patrons.

SHIFTING TO THE WORLD OF WORK

I want to take this opportunity to shift my focus to the world of work. Many of those attending the BIALL annual conference in June worked in libraries that are part of the workplace—in the private sector, higher education sector, government, and so forth. Therefore, I want to touch on the transformations taking place in the world of work before explaining how the library and the workplace continue to influence one another. To do so, I will explore three characteristics of the modern workplace: holistic, agile and virtual. I will then explore the role of the library in the workplace, before investigating the way in which design can play a part in creating a 21st century office library.

Figure 3. Halifax Central Library, open and transparent building.

Holism: individuals bring their ‘whole person’ to work

The first proposition is that companies are expected to provide spaces that support their employees’ professional and personal aspirations. This means they must tune into the values, motivations and interests of their staff, and respond to their personal and professional needs in order to attract talent and retain employees. Companies not only provide the best amenities, but also a certain qualify of life.

Figure 4. Illustration of flexible working practices.

For example, Facebook is considered the best place to work in the world. Employees explain that they work very reasonable hours, and their worth at the company is not measured by the amount of hours they log in each period. Instead, it is measured by the quality of their input. Indeed, Facebook reportedly tells its employees that they need to get enough rest and sleep each day to keep energised and consistently deliver the best version of themselves.Footnote 4

Agile: workspaces (within and beyond the office) support a widening range of functions

The second proposition is that open plan offices are giving way to dynamic, activity-based working spaces to suit different working styles. Contemporary offices have open yet separate spaces that allow for collaboration, inspiration and mobility.

For example, Steelcase's newest office in Munich promotes what it calls the ‘palette of place’. This 14,400 square metre space is designed for employees, dealers, customers, influencers and guests to lead, learn and innovate together. The Learning + Innovation Center is ‘a cross-functional plan that creates a haven for new ideas’.Footnote 5

Figure 5. Steelcase's Innovation Center.

With opportunities for individual and group collaboration across time zones and continents, the Steelcase office is a place that fosters a culture of innovation through the creation, sharing and testing of ideas. To me, the design and layout of the space appears very close in form and function to the contemporary library, with lounge areas dedicated to collaborative working.

Virtual: the workplace now extends beyond the confines of the office

The third and final proposition is that cities are being designed to support the dispersal of workplace activities. Over the last ten years, co-working spaces have become popular for this reason, as they provide individuals and organisations with the opportunity to come together to share knowledge, exchange ideas and collaborate across boundaries and networks.

For example, when Second Home launched in 2014 at a site just off Brick Lane in East London, it quickly became the coolest spot for young businesses in the British capital. This 2,400 square metre space brings together thinkers, makers, artists and entrepreneurs. It has a canteen restaurant where people are encouraged to share ideas.Footnote 6

Whilst many might regard it as a co-working space, it is perhaps more of a business accelerator. Indeed, it has attempted to distinguish itself from the co-working market with strategies such as the receptionists not referring to it as a ‘co-working space’ (which is how its competitor WeWork describes itself), and the impressive events programme, which makes it as much a casual members’ club as a space for hard work.

However, these characteristics are not without their challenges. In particular, companies that embrace holism, agility and virtual working are often noisy places in which to work. It has been reported that noise has the greatest impact on productivity within an office setting.Footnote 7 This is perhaps where the office library really comes into its own. Does it present staff with the opportunity to have access to some much-needed quiet space? In the next section, I explore the role of the library in the workplace.

LIBRARIES AT WORK

The office library can potentially provide individuals with quiet space for focused work and study. This is particularly important in open plan offices where productivity is often compromised because it is noisy. However, to truly provide staff with solitude, the library would have to be fully enclosed. There are some examples of enclosed library spaces within larger library complexes at universities. For example, James. B. Hunt Jr. Library offers its students a quieter Graduate Student Commons, which they enter using an access card. However, this kind of provision is unlikely in an open plan office. Instead, libraries in offices are becoming destinations for activity-based working.

The office library provides individuals with the opportunity to collaboratively work and innovate. It can also offer staff with social spaces that might be used for networking—which is considered productive rather than ‘lost’ space. For example, Arup's Sydney office recently won an award from the Australian Libraries Association for its library space in recognition of its design and services to the business, and to the contribution to the library community as a whole. The judges noted that, ‘The openness of the collaborative work spaces provides ample opportunity for gatherings, staff manipulation of work spaces (away from traditional desk areas) and facilitates a studio-based learning and collaborative environment not unlike most schools of architecture’.Footnote 8

How to decide what function your library should perform in the office? There is no formula.

Collect data

Staff need data to understand the needs of their community. Librarians and architects need to collect as much data as they can on how a service and space is currently used and areas in which it can work better. This data enables the custodians of office libraries to invest in services and spaces are needed most.

Prioritise simplicity

The changes to the library do not have to be huge to have an impact. Even the smallest adjustments to the design and layout of the space can make a difference, such as adding LED strips to the open stacks. These small changes ensure that the library continues to be relevant and, of course, user-friendly.

Always innovate

Don't be afraid to experiment. Prototype new services and spaces in light of data that suggests that staff preferences have changed. Indeed, whilst noisy, an open plan building also allows for more flexibility—so staff can change the function of an area throughout the day. This gives plenty of scope for rearranging the furniture to provide staff with a new offering.

BLURRED BOUNDARIES

In conclusion, I have described how experience matters now more than ever. This is because people have greater flexibility over where they work, live and learn in a digital age. They can vote with their feet, and if a space doesn't provide the right amenities and services, customers will quickly move on. Librarians need to work closely with their patrons, and establish a transparent relationship and a hands-on approach that can help them determine what the consumer wants.

Digital technology will radically change how we create, use and access information. This means librarians must take into account the need to access information at a distance from the library, and provide customers with the unique experience of engaging with information in a memorable and meaningful way—through play. A good example of this is the Delft Library Concept Center innovation, Tank U—a download station that uses Bluetooth. Tank stations can be placed in different locations outside the library and customers can download installed content from them at any time.

I have explored how libraries are being designed to accommodate different learning and working practices. New buildings are being designed so that they can be physically adapted over decades. The layout of the new public libraries is open plan, with some zoning achieved through furnishing, so that each space can be used by anyone. The furniture is mobile so that it can be moved around by the customers. The most flexible spaces are those that are neutrally decorated. Even staff are flexible in the way that they deliver services, and they are being encouraged to be more spontaneous in their approach to service delivery.

Finally, librarians are becoming responsive to their customers’ need to play more of a role in decision-making, and are empowering them to curate spaces and events. This has raised concerns regarding where to draw the line. This emphasis on ownership also extends to the design of the building and spaces. It is important that customers can see all the floors in a building as they enter, so they can guide themselves around it. Individuals also benefit from seeing each other in the space, because this provides them with a sense of autonomy, belonging and empowerment. It also enables staff to be more helpful.

There are clear overlaps between the changing role of public libraries and the function of libraries within an office setting. Increasingly, office libraries are being seen as a place for collaborative work and innovation. In this sense, just like the public library, the office library is becoming a space for meeting. It is place of intersection, where people come together, where the life of the office unfolds. As with new public libraries such as DOK 1 (Urban Mediaspace) in Aarhus in Denmark, the office library could be regarded as a buzzing ‘living room’, accessible to everyone who comes by.

Before embracing these changes, it is necessary to engage with staff to understand what they really want from their office library. Collect data on the behaviours and habits of your patrons—their borrowing preferences and visiting times. Ask them questions. Don't make too many changes to the space all at once. The simplest designs and layouts are the most effective. Try moving around a few chairs and tables in the first instance. Finally, don't be afraid to experiment. Install a new piece of furniture and watch how people respond to it. Do they use it?