Introduction

Divorce is an international concern of scholars of family issues. Recent decades have witnessed an increase in divorce in both Western and Asian societies (Quah Reference Quah and Ghaleb2003). In Western societies, causes of divorce include macro-structural factors (i.e. law, economic cycles and the institution of the family), gender roles, demographics such as sex ratios, the life course and family process (i.e. cohabitation, premarital pregnancy and childbearing, parental divorce, age at marriage, age and marital duration and child sex preference) (White and Rogers Reference White and Rogers2000). In Asian societies, previous studies have identified prevalence and alternative determinants of divorce in different national contexts, which include cultural and demographic, socio-economic and life course determinants (Hirschman and Teerawichitchainan Reference Hirschman and Teerawichitchainan2003; Jones Reference Jones2007). Existing literature suggests that increasing divorce represents a central social change in countries across the world. This is due to a reduction in the stigma attached to divorce, lower levels of partner intimacy, decreasing personal sacrifices made in marriages (Amato and Previti Reference Amato and Previti2003) and personal readiness to accept marital break-up due to increasing individualization in marriage (Friedman Reference Friedman, Skolnick and Skolnick2009). In recent years, divorce has decreased slightly in several developed societies such as the USA, the UK, Sweden and JapanFootnote 1 due to economic dissatisfaction as well as changes in the perception of marriage and gender roles. At the same time, the divorce rate remains high in several Asian societies such as China.Footnote 2

The case of Vietnam is both unique and representative in this social context. It is unique in the sense that the country's modernization trajectory has been the result of dramatic chaos in its modern history. The country was strongly influenced by Confucianism in the feudal period before 1945, then transformed directly from feudalism to socialism through the historical events of wars during the 1950s–1970s. It was reunified in 1975, underwent social hardship and developed a controlled, subsidized, bureaucratic and centrally-planned economy with a closed door policy in the early 1980s. Vietnam then implemented the “Renovation” (Đổi Mới) period beginning in 1986 with a socialist-oriented market economy, open door policy and international integration. The country is now strengthening this stage of industrialization and modernization.

One may argue that the country exhibits mixed features of a first modernity (i.e. ideology of full employment, nuclear families and a collective solidarity), a second modernity (i.e. industrialization, a market economy and cultural globalization) (Beck Reference Beck1992) and a compressed modernity in terms of the disparate coexistence of various levels of human existence and transitional values (Chang Reference Chang2010) in which new institutions have yet to be fully established while old institutions remain influential (Tran Reference Tran Thi2014).

For instance, people with lower socioeconomic conditions, such as people who are elderly, tend to have lower education, live in rural areas and experience a lower level of living standard show stronger patriarchal norms including career promotion prioritized to men while placing family chores on women, intergenerational coresidence arrangement preference, gender-based division of labour, higher fertility, place higher value children more instrumentally and extoll strong family and community cohesion (Trần Reference Trần Thị2019). Meanwhile, those with higher socioeconomic conditions value housework sharing; accept single mothers, premarital sex and cohabitation (Nguyễn H.M Reference Nguyễn2019) and prefer dual incomes (Trần Reference Trần Thị2019). The Vietnamese family is showing a clear trend towards nuclearization with an average family size of 3.4 people (GSO 2019), higher individualization in mate selection and significant increases in the emotional values of children as opposed to the instrumental value of children (Trần Reference Trần Thị2019). At the same time, influences of Confucianism and feudalism, such as the preference for male children, remain, especially in the Northern provinces. In 2009, the male birthrate was 110.5% of females (GSO 2011b), which had increased to 111.5% by 2019. The Northern regions, including the Northern Uplands and Red River Delta, show a stronger sex imbalance at birth (i.e. boys 114.2% of girls, and 115.5%, respectively) than the Southern area does (GSO, 2019). The persistence of traditional values despite modernity demonstrates complexity in Vietnam's development path, which is also reflected in changes in divorce in the country, notably when looking at divorce from the macro level and over long period of time.

Recent studies on divorce in Vietnam show that, although divorce has long been culturally discouraged and limited, it has increased rapidly after the Renovation of 1986, with more divorces occurring in urban areas than in rural areas (Vũ Reference Vũ2019). Divorce procedures are easier in urban residential areas, especially in the South, while the process of collective involvement remains in the North. Women's initiation of divorce proceedings, regardless of social circumstances, was observed in the North during the period 2000–2010 (Tran Reference Tran Thi2014) and is confirmed by the current study of the South. Of all divorce proceedings (N = 6,439), 68.7% were initiated by women during the period from 2009 to 2017. Remarriage after divorce in Vietnam is low with 15% remarried and less than 10% cohabitated without remarriage (Trần Reference Trần Thị2020a). Most women regard child custody as their duty even after divorce and are ready to make the necessary sacrifices in pursuit of their own happiness and emotional satisfaction. A proportion of 69% of divorces grant child custody to mothers after divorce in the South of Vietnam and it is also the prevailing trend in the North (Tran Reference Tran Thi2014). Many children assigned to live with their fathers subsequently move to live with their mothers (Trần Reference Trần Thị2020a).

This current literature, although providing macro trends, remains limited in its engagement with the micro-level perspective of individuals and lacked of long-term trends in historical Vietnam. This paper is the first to challenge this scarcity of data on divorce histories by bringing the macro-structural processes of modernization, individualism and gender equality into contact with a culturally and historically contextualized analysis of the trends and reasons for divorce and social transformation. The paper first sketches the research context, which provides cultural and social background information for the study. The paper then discusses the theoretical framework and the data and research methods to be used in this analysis. Research findings are presented to show the trends of divorce and reasons for divorce. The discussion and conclusion elucidate the contributions and implications of the study.

Research context

Vietnam witnessed unprecedented social and political turmoil during decades of war and social upheaval in much of the twentieth century. These experiences challenged traditional social norms, modernization process and influenced social perception of and behaviour related to marriage and the family.

In the feudal period, regulations generally allowed a husband to divorce his wife, although there were some limitations (Nguyễn Reference Nguyễn1982). It was easy for the husband to divorce his wife, yet not easy for wives to divorce their husband. In fact, divorce was not widely accepted because marrying a wife was costly. The wife was able to make a significant contribution to the family economy, and polygyny allowed men to have concubines to make up for perceived weaknesses or faults of the wife (Insun Reference Insun1994). Vietnam's unprecedented history of wars that fought to protect the country's freedom and independence saw generations of men fighting on the battlefields. At this time, women were socially expected to be faithful to their husbands and sacrifice themselves and their individual happiness for the collective.

The country declared its independence from France in 1945 and directly transferred from feudalism to socialism with significant changes of institutional settings. It promulgated its first Constitution in 1946. The Constitution attempted to promote gender equality, which challenged strong patriarchal norms in feudal marriage. Between 1945 and 1975, the country was engaged in the French War and then the American War, and fought to gain independence and reunify the North and the South. During this period, the new socialist regime in the North issued policies and promoted ideologies that actively challenged “feudalist and backward” family practices regardless of the continuing influences of Confucianism in organizing family life, while the South also experienced a taste of Western democracy and capitalist economy during the American occupation. For example, the first Law on Marriage and the Family in 1959 banned all forms of traditional marriage such as polygyny, child marriages and arranged marriages and promoted love marriages and gender equality, as well as the discouragement of pregnancy to curb population growth in the North. These laws were extended to the South after re-unification. The Law was considered a “revolution,” that broke with the traditional marriage–family relationship; shaped new perceptions and tackled practices of child marriage, early marriage and arranged marriage that existed previously.

However, in this historical period, changes in family size, structure, fertility and norms were slow, given that the country was entrenched in wars and there was political division between the North and the South. The North instituted socialism, sent military forces to the battlefields and maintained production to support the Southern battlefields based on a strong sense of collectivist culture while the South engaged in a capitalist economy under American occupation.

After re-unification in 1975, the whole country began to embrace socialism while coping with socioeconomic hardships due to devastation of infrastructure and production caused by more than three quarters of the twentieth century passing in a state of war, followed by the experiencing of failed centrally planned socio-economic policies. During this period, Vietnam's government continued its movement towards a more “progressive” form of family life through legislation and policymaking. However, modernization and social awareness of modern marriage were impeded due to such the socio-historical context.

Since the introduction of the Renovation in 1986, Vietnam has undergone a transition from a centrally planned economy to a socialist-oriented market economy. The Renovation has brought rapid economic development and transformed Vietnam from a very poor country to a lower-middle income country in a quarter of a century. In this period, the state has adopted various policies such as the 1986 Law on Marriage and Family and its amendment in 2014, the Law on Gender Equality in 2006 and the Law on Domestic Violence Prevention and Control in 2007. Such legislation significantly redefined gender roles and family relations. Vietnam has dramatically expanded its formal education and employment systems, which have seen unprecedented levels of educational achievement and labour force participation for women. In 2019, the gender gap in education has narrowed such as the average school-year of male is 9.4 years and of female is 8.7 years; while there is 72.4% of the women are now in the labour market, compared to 82.3% of men (GSO 2018, 2019).

A growing literature finds traditional patterns of prohibited premarital sex, arranged marriage, coresidence of newly married couples with the groom's parents, gender inequality, strong patriarchy, the birth of many children, preference for male children of male children, patrilineal relations and Confucian filial piety under the Confucian cultural heritage have significantly declined (Hirschman and Nguyen Reference Hirschman and Nguyen2002; Tran Reference Tran, Liljestrom and Lai1991). New models of family life are on the rise (GSO 2018). Although extended family patterns have not disappeared, nuclear and skip-generation families are increasing. The average household in 2009 comprised of 3.8 persons, which had decreased to 3.5 by 2019, with larger sizes in rural households in the Northern Highlands and Mountain areas and the smallest household sizes in the Southeast and the Red River Delta (i.e. 3.4 each) (GSO 2019). The country also has seen a growing prevalence of alternative family forms such as cohabitation, single parenting and transnational marriage (Trần Reference Trần Thị2019), which were absent or very rare in the past. The mean age at first marriage is 26.4 years for urban residents and 24.5 for their rural counterparts and both ages are higher in the South than in the North. The mean age of women at first marriage was 23.1 years (GSO 2019) and at the birth of a first child was 24.7 years in 2014 (GSO & UNFPA 2016). As a result of higher levels of schooling, better health care, increased urbanization and greater exposure to modern forms of mass communication, fertility has dropped rapidly from 6.3 children per woman in 1960s to 2.09 children per woman in 2019 (GSO, 2019) and it is lower in the South. The average life expectancy is 73.6 (GSO 2019) and the country is ageing fast with the proportion of population aged from sixty increased from 7.1% in 1989 to 13.5% in 2019 (GSO 2018) yet the pension system can cover only about one-fourth of senior citizens' needs (Kidd et al. Reference Kidd, Gelders and Tran2019) and another one-fourth of older adults receive monthly social allowances. In the context of such a limited social security system for older adults and with strong filial piety placing responsibility of parental care on children, it is understandable that Vietnamese people highly value their children, which influences the consideration of divorce.

Those macro changes in the legal systems, gender roles, the institution of the family and socio-economic development have greatly influenced individual perceptions of marriage patterns, including divorce.

Theoretical background

Modernization theory

Changes in divorce during the complicated trajectory of Vietnam are first contextualized by modernization theory, which helps to explain social and cultural individualization. First, modernization might be expected to contribute to marriage stability and then reduce divorce rates because of the rise of conjugal family systems (Lee Reference Lee1982) the increasing autonomy of young people (Jones Reference Jones2007, Reference Jones1997); the increase freedom from extended kin control (Goode Reference Goode1963); the increase age at marriage (Jones Reference Jones1997); expanded educational opportunities; urbanization and greater freedom in mate selection (Goode Reference Goode, Merton and Nisbet1971, Reference Goode1993; Hirschman and Teerawichitchainan Reference Hirschman and Teerawichitchainan2003). In the long run the trend towards egalitarianism that accompanies modernization and the replacement of patriarchies can improve women's status and create a socio-cultural context for divorce. Various measures of modernization such as increasing women's economic independence, ideological emphasis on self-fulfilment through relationships and individual choice as well as the weakening stigma of divorce (Goode Reference Goode, Merton and Nisbet1971) may shift the tide towards less stable relationships. Modern marriage based on love and affection may also be more unstable than one based on socio-economic or other needs (Trent and South Reference Trent and South1989). The combination of these two factors could determine the trajectory of divorce prevalence in Vietnam.

The changes in marriage, family and divorce in Vietnam are believed to closely relate to the modernization process. Vietnam transformed directly from feudalism to socialism in the historical events of wars during the 1950s–1970s, the Renovation in 1986 and the following decades of socialist-oriented market economy with a “shortened” strategy of modernization and industrialization, which can be called “complex” modernity with the combination of socialism, Western values, vestiges of feudalism and diversification of cultures among ethnic groups.

Socialism formulates new values of marriage and family by providing legal and institutional settings such as those related to gender equality and increasing social status for women. A market economy transforms the essence of economic functions of the family from a production to a consumption unit (Nguyễn C.T. Reference Nguyễn2019). High employment for women and a nuclear family attribute to couple's intimacy and care burden. The open-door policy and globalization strengthen people's perception of the Western self-lifting individualization that can enjoy marriage emotionally.

Fast and complicated social, economic and policy changes at the macro-level and complicated coexistence of family values and norms, provide a unique context within which to explore how these different levels of structures and factors may impact the divorce prevalence and the reasons it has changed in Vietnam in recent decades.

Collectivism and individualism

It is important to understand the notions of collectivism (tính tập thể, tính cộng đồng) and individualism (tính cá nhân) in relation to modernization and Confucianism, as they are manifested in the interpretation of disparate marriage and family behaviours in contemporary Vietnam. A recent study of collectivism and individualism in Vietnam showed that collectivism still prevailed over individualism among Vietnamese and Vietnamese women are more collectivist than men, but these two variables are complicated when disaggregated by North and South and by rural and urban areas (Do and Phan Reference Do and Phan2002). Vietnam's collective culture is rooted in Confucian ideology, which was strongly oriented around families and communities, strengthened through generations by the need to mobilize collective strength for wars to protect freedom and independence in Vietnam. Collectivist culture can be seen in important individual events such as family meetings about abortion (Gammeltoft Reference Gammeltoft2007), divorce (Author Reference Tran Thi2014), weddings and other important decisions such as house construction (Nguyễn H.M. Reference Nguyễn2019) but individualization is rising.

Gender equality

For many Asian women, divorce attracted social stigma and could be seen to indicate the betrayal of the husbands' family. Some Asian countries share a heritage of, or are heavily influenced by, Confucianism, the values of which centre on male domination, filial piety and collectivist goals as opposed to individualistic fulfilment (Xu and Lai Reference Xu and Lai2002). Under a patriarchal familial system which can be identified by its androcentric values, women are often viewed as temporary residents of their natal homes. Therefore, marital roles are prescribed by an unequal gender ideology inherent in the institution of marriage in East Asia (Yang and Yen Reference Yang and Yen2010). However, with increasing educational attainment, increasing economic opportunities for women and more tolerant attitudes towards behaviours such as delayed marriage and maternal employment, the conventional gender roles in marriage seem to be rather restricting and obsolete to many women (Tsuya et al. Reference Tsuya, Mason, Bumpass, Tsuya and Bumpass2004), although are still often burdened by the dual pressure of house work and childcare duties (Lee Reference Lee2006).

Vietnam has also been influenced by Confucian ideology, which ensured men's power and limited gender equality by following cultural norms. Confucian ideology and dogma related to what a proper Vietnamese woman should do include several principles followed from their childhood to their death. Foremost is the principle of “chastity” (trinh) including the defence of virginity before marriage, absolute faithfulness towards one's husband, alive or dead and a purity of spirit. There are golden rules for a woman's life such as the “three submissions” (tam tòng) which include obeying her father before marriage, her husband during marriage and her son in widowhood (tại gia tòng phụ, xuất giá tòng phu, phu tử tòng tử). She must exhibit four virtues (tứ đức) including labour/work (công); physical appearance (dung); the use of appropriate speech/words (ngôn) and moral behaviour (hạnh). In addition, there existed hundreds of precise oral moral prescriptions that parents and relatives repeated to their daughters during their childhood and adulthood. For instance, “men and women should remain physically distant” before marriage. Once married, a woman had to learn to accept a concubine or concubines into the family (Marr Reference Marr1981).

As a result, there is limited gender equality in this cultural fashion, although several studies also emphasized the power women held in certain social arenas (Tran Reference Tran, Liljestrom and Lai1991), such as their important role in the family economy and in bearing and rearing children. These are reflected in proverbs saying that woman are the “household general” (nội tướng), and the “money key-keeper” (tay hòm chìa khóa) in the family.

Since the declaration of independence in 1945, gender equality is a priority in the political agenda of Vietnam‘s government. Gender equality and the status of Vietnamese women have improved significantly over time (UN Women 2016). Women have higher levels of involvement in the labour market (GSO 2019); migrating women pursue higher social status; family investment to boys and girls has become less unequal (Nguyễn H.M. Reference Nguyễn2019).

At the same time, feudalism and Confucianism secure the long-lasting vestiges of gender inequality, preference for male children and double standards for women. House chores and child-care are usually undertaken by women (Nguyễn H.M. Reference Nguyễn2019), although they are increasingly migrating and participating in the labour market (GSO 2019), and there is a great lack of paid child care services for children under 3 years old (UN Women 2016). The division of labour in the family is still predominantly tradition, despite the legal and policy framework that has prioritized gender equality in Vietnam for decades. Women tend to accept the “golden” stereotypes of feudal and Confucian gender-based actions and behaviours, such as agreeing to create conditions for husbands in their careers, although there is no evidence of deficiency in female's performance in employment (Trần Reference Trần Thị2019). Social expectations consider men as the family economic pillar although, in fact, women contribute almost equally in the labour market while receiving lower payment (GSO 2019). There is the imbalance of the sex ratio at birth (GSO 2019) and preference for male children prevails among women with better educational attainment and living standards (GSO 2011b). This is facilitated by better access to health facilities and diffusion of prenatal sex selection and better access to and ability to afford the technology of sex selection while their attitudes of male preference has not yet declined under influences of social norms (GSO 2011a; UNFPA 2010). The low representation of women in the political system persists.

However, recent studies still show the persistence of gender inequalities and gender stereotypes in family and social relations. With the influences of modernization, legal changes and comprehensive international integration, old and new values, as competing forces, are operating within the realm of marriage and the family in Vietnam.

Data and method

This paper first analyses how divorce in Vietnam has changed through modernization, examining trends in divorces rates in Vietnam. These are calculated from the raw statistical data of reported reasons for divorce both from the Vietnam People's Supreme Court in the period 1965–2017 and from annual Vietnamese population statistics. The crude divorce rate (CDR) in a specific year is defined as the number of divorces per 1,000 of the total population in the country in the specified year. The general divorce rate (GDR) in a specific year is defined as the number of divorces per 1,000 of the population aged 15 years and above in the specified year (Shryock et al. Reference Shryock, Siegel and Larmon1975).

The analysis then compiled a database of every divorce case at six urban and rural districts in the Can Tho province. In total, there are 8,993 divorce cases, of which 64.2% were divorced couples in urban districts and 35.8% were divorced couples in the rural districts. The analysis highlights changes in the reasons for divorce in the South in comparison with previous divorce studies in the North of Vietnam under the pressure of the forces of modernization and individualism in Vietnam from 1998 to 2017. These statistical findings are further interpreted qualitatively based on thirty interviews with male and female divorcees, conducted in 2017 and 2018. The sampling was selected based on a list of divorcees at one urban and one rural district court in the North (i.e. Hanam province and Hanoi city) and one urban and one rural district court in the South (i.e. Can Tho and Ca Mau provinces). The interviews were arranged by official introduction of the district People's Court and the Provincial Women Union, two institutions which normally have contacts with divorced people during divorce proceedings and after a divorce in Vietnam. The interviews were arranged at each divorcee's home and conducted in-person by the author.

Research key findings

Increase in the incidence of divorce in Vietnam during modernization

The divorce rate is gradually rising in Vietnam, as shown in Table 1. The CDR was low in 1960s and 1970s in the war time at approximately 0.37. In the 1960s, the divorce rate was influenced by a strong patriarchy protecting men's power, and the sacrifice of women after a long time in the social context of acceptance of polygyny with very limited cultural room for the idea of divorce. At the same time, women were increasingly protected and aware of their rights in marriage and the family, including divorce after the introduction of the first Law on Marriage and Family in 1959. However, the country division between 1954 and 1975 may have limited the communication of the law and reduced its effectiveness regarding marriage and the family.

Table 1. Prevalence of divorces in Vietnam, 1965–2017

Source: Author calculates from:

a Annual Statistics of Vietnam People's Supreme Court.

b Statistical Yearbook 1980–2018, GSO.

c GSO. Major findings: Population change and family planning survey 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2016 and 2017.

Although the low prevalence of divorce in some countries can be linked to increasing age at marriage, educational expansion, urbanization and greater freedom to choose marriage partners (Hirschman and Teerawichitchainan Reference Hirschman and Teerawichitchainan2003; Jones Reference Jones1997, Reference Jones2007; Yi and Wu Reference Yi and Deqing2000), there are social, historical and cultural factors accounting for the low divorce rates in Vietnam before Renovation. For a long time, Confucian ideology and feudal marriage in Vietnam, including arranged marriages, very limited intimacy before marriage, polygyny, gender inequality for women and low educational attainment of women, limited women's right to divorce.

The period 1960s–1975 was a special historical period of Vietnam in terms of social structure, work allocation and ideology, which had strong influences on family relations and individual behaviours. The country was divided into two regions. The North was “liberated” in 1954, and entered a period of transition to a socialist planned economy and supported the revolution in the South. The South was occupied by the United States and followed a market capitalist economy. In the rural North, there were millions of young men leaving their homeland to join the army and go to the battlefields, especially after the full mobilization in 1965. In rural areas, women, children and the old stayed behind. Women became a major force in the labour force, the local government and the family as replacements for men who were at the front. They served in the local government and public sector (i.e. the proportion of women representative in the National Assembly peaked in the 1975 term), worked on the cooperative farms to send food and essential items to the fronts in the South, and served as breadwinners while taking care of older parents and children in their families. The specific context of the Vietnamese history of wars, which for centuries were necessary to assure the independence and freedom for the nation, placed the responsibility of caring for children and families on women while men went to the fronts. This asked for the sacrifice of individual happiness for the support of collective and family issues. This special historical period contained the revolutionary culture, a culture created by social equality, by the spirit of all for the front lines (tất cả cho tiền tuyến), and the collective ownership. It was a culture combining patriotism and socialism while collectivism adds another dimension to low divorce rates in the society.

However, there were still barriers to achieving the higher status of women. A recent survey among 817 people in the North who got married between 1960 and 1975 measured the importance of the fidelity of women to their husband and the country in the context of about two-thirds of newly married couples lived apart (Trần and Nguyễn Reference Trần Thị and Nguyễn2020) due to the war. Young married women stayed with the husband's family and were controlled strictly by the clan and villagers to ensure their virtue and loyalty to the soldiers in the fronts. Even fiancées and girlfriends of soldiers were restricted in this way. Divorce was a taboo in this social, historical and cultural context.

The CDR increased slightly by around 0.4 in 1980s and 1990s after the country reunification and the introduction of Renovation. The government strengthened the perception of “progress” in marriage and family by various ways including adopting a policy to reduce the population growth rate in order to control the maximum number of children a couple could have (i.e. the two child policy) regardless of cultural norms, and the introduction of the movement of “cultural family” that promoted family stability and did not encourage divorce.

In this period, Vietnam coped with the severe consequences of 30 years of war, restructured the infrastructure and reorganized the poor and backward economy towards socialism while confronted with a border war in the late 1970s, and international isolation. Although the country was unified, 39.8% of couples still lived apart in the first 5 years of marriage because the husband was still serving in the military or assigned to migrate to new economic zones (Trần Reference Trần Thị2020b). High poverty, high inflation and low living standards were so serious that there was not enough food for daily living even though more than 80% of population was working in agriculture. The shortage situation was even more serious in the South after changing of the economic management modality (Nguyễn Reference Nguyễn1991).

Marriage and the family were influenced by such hardship and challenging circumstances. Thus, the slow increase in and low rates of divorce in Vietnam during the American war and the following subsidized time were affected by vestiges of feudalism and Confucian ideology competing with the socialist ideology in an unprecedented historic background of war, economic hardship and social crisis. As such the social structure did not prioritize individualism but still the collective priorities of national freedom and tackling the social crisis leading to hunger and poverty in most families at that time remained very hard to manage.

The miracle of socio-economic development after Renovation 1986 and the open door policies led to significant changes in family institutions. Divorce increased constantly in both numbers and rates (Table 1). In 2000, the CDR was 0.66 and it increased to 1.05 in 2009 and 2.22 in 2017. The GDR rose from 0.97 in 2000 to 1.49 in 2010 and continued to increase to 2.92 in 2017 (Table 1). During this time, the levels of modernization, urbanization and economic development increased, alongside an increasing age at marriage, educational expansion, greater freedom to choose marriage partners and increasingly individualized intimacy, women's rights and individualism. Those social changes associated with modernization have eroded traditional norms and may account for the increase in the incidence of divorce.

As individuals become more liberal and autonomous in their marital decisions, social opinions about divorce become more open. In this context, divorce is becoming a reflection of rational and autonomous decisions to pursue personal happiness. Divorce is no longer a social stigma and is relatively easy to obtain, especially in the more modern settings such as urban areas, as stated in the case studies from my research.

Divorce has never been easier than now, especially if you do not have a property conflict. Unless you have to divide property in court due to not being able to compromise, divorce is so simple. Reconciliation is kind of a required procedure. In my case, I feel it was simple and so was the case of my friend (Ms. Tr. born in 1982, university educational level, counsellor, Hanoi, divorced in 2015).

Although divorce in rural areas is most often a collective decision with the involvement of family meetings, reconciliation procedures and couples' negotiation (Tran Reference Tran Thi2014), divorce in urban settings is more likely an individual decision with less complicated divorce procedures. The couple may not undergo the entire process of meetings, reconciliation and so on when applying for a divorce. They may, however, still seek advice from family members and intimate friends on relevant issues related to the divorce, such as child custody arrangements and property settlement, and adjustment after the dissolution of the marriage.

It's very quick. They called me to reconcile twice, prepared the meeting minutes of the reconciliation attempt, and then granted the divorce decision after one week. The divorce decision is just a paper but you know, (getting) the marriage registration paper is very nice, but the divorce one is (cry) It's so torturous (Ms. Th, nurse, born in 1958, one daughter, Hanoi, divorced in 2014).

Meanwhile, the fast increase in incidence of divorces after Renovation represented a release of repressed individualism in various dimensions that can be seen by changes in the reasons for divorce in Vietnam in recent decades.

Changes in reasons for divorce

In Vietnam, divorce had been judged on the basis of “fault.” Couples generally need to report reasons for divorce in the divorce application. The main reasons for divorce recorded in Vietnam's family court system are: domestic violence, adultery, childless marriage, economic difficulties, addiction, social problems and effective separation due to one spouse being missing or imprisoned (Vietnam People's Supreme Court Reference Vũ2018). Over time, the reasons for divorce in Vietnam have changed dramatically, moving from the old-fashioned divorce to modern divorce and exhibiting the influence of modernization and individualism in divorce. Differences in lifestyle also entered the records as a reason for divorce from 2007 onwards.

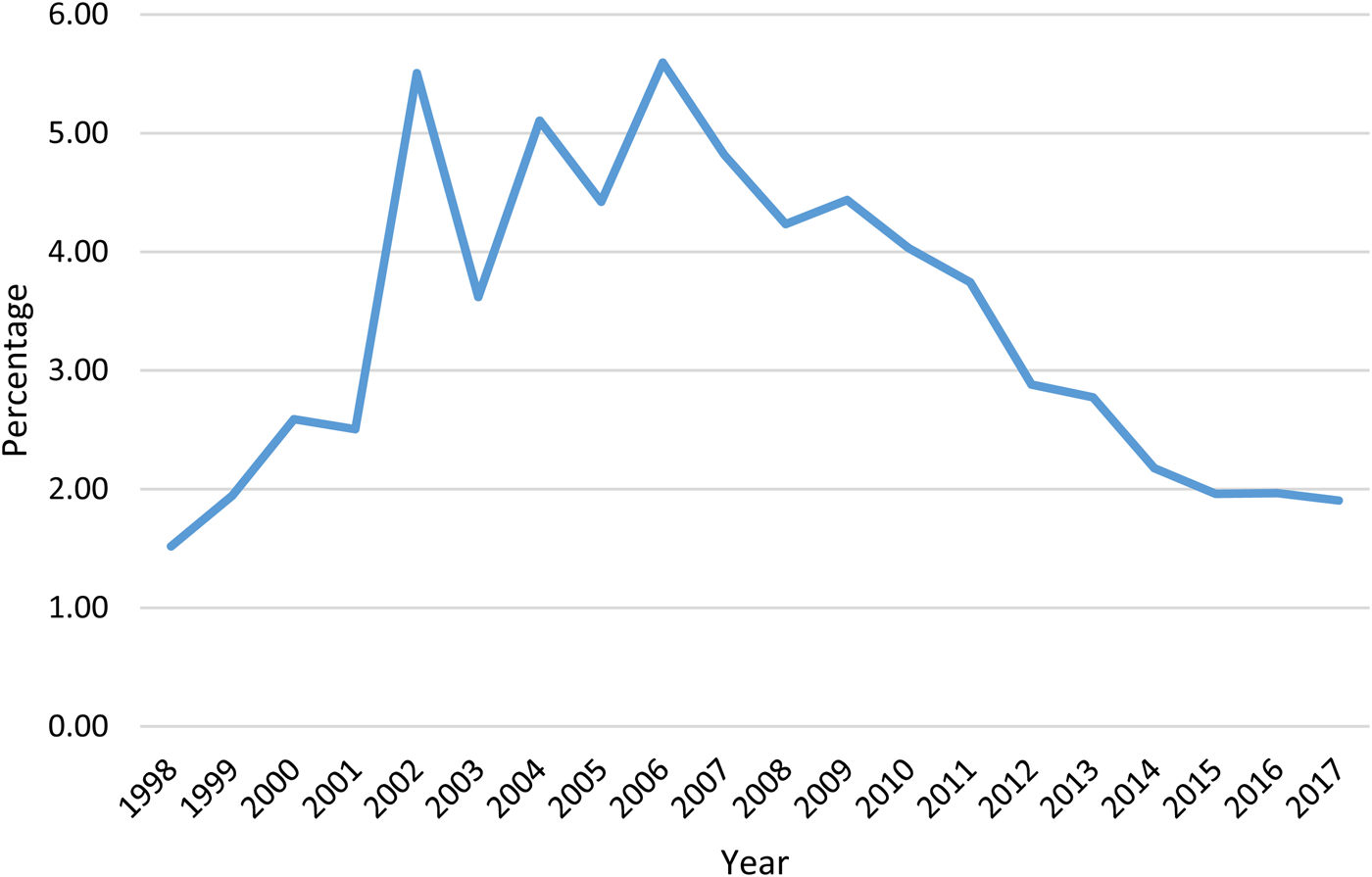

First, divorces related to the feudal and Confucian ideology such as forced marriage (i.e. arranged marriage), polygamy (i.e. concubines) and child marriage (i.e. getting married before the age of eighteen for women and twenty for men, according to Law on Marriage and Family 1959), tended to decrease sharply over time (Fig. 1). With the introduction of the first Law in 1959, those kinds of marriage were prohibited, although in reality the law was interrupted in communication due to war and country division. As increases in social awareness, gender equality and supervision of law implementation occurred, many of those marriages were resolved through divorce. Since 2005, such divorces have not appeared in statistical reports, which reflect social changes in marriage and the family.

Figure 1. Percentage of divorce related to feudal marriages by total divorces in Vietnam, 1998–2004.

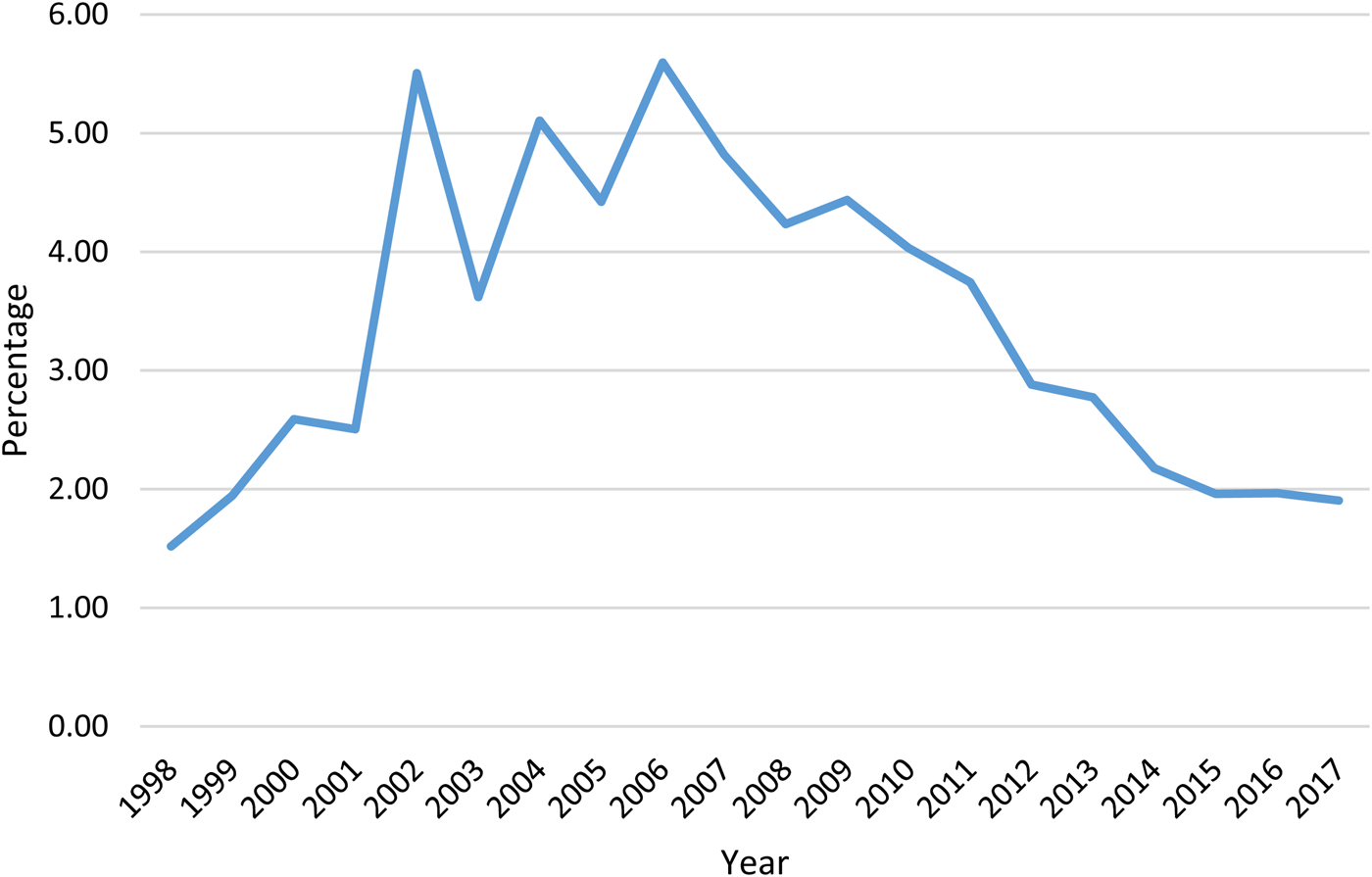

Second, divorces rooted in the patriarchal culture, such as domestic violence, tended to drop sharply when new laws were applied but remain a significant reason for divorce (Fig. 2). Domestic violence ranks the third among all reasons in the South (i.e. 5.6%) in the period 2009–2017 (Table 2). The trend even ranked the second (9.2%) among all reasons and was three times higher in the rural areas than in the urban areas, as confirmed by one study on divorce in the North of Vietnam in the period 2000–2009 (Tran Reference Tran Thi2014). By looking at the reported reasons for divorce over such a longer period at the national level, this paper confirms the significance of domestic violence in divorce.

Figure 2. Percentage of divorce due to domestic violence by total divorces, 1998–2017.

Table 2. Percentage distribution of divorce reasons of the South Vietnam, period 2009-2017 (N = 2,608)

Source: Author calculates from divorce profiles of Cantho People's Court from 2009 to 2017.

Previous literature provides significant evidence of domestic violence against women in Vietnam in all regions, in both urban and rural areas and in families of all income levels (GSO 2010; Molisa et al. 2020). There were proportions of 58% of ever-married women experience physical, sexual and/or emotional violence in their lifetime; 27% of ever-married women had experienced one type of violence (physical, sexual and/or emotional), 32% had experienced physical violence by their husband and 10% had experienced sexual violence (GSO 2010). Before 2007 when the Law on Domestic Violence Prevention and Control came into effect, divorce due to domestic violence accounted for more than 50% of the total divorces per year. In the milestone year 2007, it sharply fell to 7.54% (equivalent to about 40,000 cases) and decreased gradually to 2.86% (equivalent to 6,000 divorces) in 2017 (Fig. 2). The situation currently shows improvements but violence against women remains.

The reason domestic violence exists is because of deep-rooted attitudes regarding socially and culturally prescribed roles, and views regarding the responsibilities and traits of men and women (GSO 2010) that formerly ensured men's power. The patriarchal culture lowered the status of women by giving the right to educate the wife to her husband from her first day of marriage (dậy vợ từ thuở bơ vơ mới về). Many husbands give themselves the “right” to control their wives by using violence if their wives do not obey or satisfy them (Tran Reference Tran Thi2014).

Case studies and in-depth interviews show that wives do not usually apply for divorce the first time they are assaulted by their husbands. Divorce due to domestic violence is often a result of serious and persistent violence by the husband towards his wife. There are many reasons for women to keep silent when being abused. They may feel the need to do so to keep the family safe, do so for the sake of their children or to save “face” for their family. The case studies also provided information on the different dimensions of domestic violence by husbands against their wives with details of the various motivations behind the abuse, such as jealously or economic hardship, among others.

He hit me very badly. I was also afraid that he would kill my parents. I tried to run away seven or eight times but could not stop (being beaten). The torture was very fierce. I bought some pills to try killing myself twice together with my kids. But I was scared that what happen if my kids died and I could not. There was a case I knew in such a situation. I was too afraid of not drinking, very miserable. I do not know why he beat me so. In my natal family there are three death anniversaries a year, which are my grandfather, my grandmother and my third brother. Whenever I went home to commemorate their deaths I was beaten. Every lunar New Year holiday, I was beaten so I had no feeling of Tet (Lunar New Year). I was living miserably (Ms. V. born in 1974, divorced in 2010, one child, not remarried).

I went out and met my neighbour and just said hello out of politeness, he saw and he went crazy so he strangled me. If my mother hadn't saved me, I would have died then, not lived until now (Ms. LTAD, born in 1981, Can Tho, divorced in 2018).

Domestic violence against women is now decreasing due to international commitments of the government and progress made in families by introducing new concepts of marriage and the family, as discussed above.

The third major reason for divorce in Vietnam is childless marriage. In Vietnamese families, children have a great meaning for marriage and the family so that the majority of married couples want to have children and in fact the average number of children per married couple is 2.24 children. The literature shows that children bring security for parents when they get older; lineage continuity as well as emotional value in terms of connecting the family and satisfying the self-fulfilment of the couple themselves regardless of the needs of the parents and the parents-in-law (Trần Reference Trần Thị2019). Therefore, the data on divorce reasons over the past two decades show that divorce due to failure to have children is a significant cause and tends to be sustained over many years (Fig. 3) in both North (Tran Reference Tran Thi2014) and South Vietnam (Table 2). Therefore, divorce is more likely in families without children.

Figure 3. Percentage of divorce due to childless and diseases by total divorces in Vietnam, 1998–2017.

The sex composition of offspring in vulnerable families may be quite important in families with a preference for male children. The in-depth interviews show that, in many cases, not having a son may lead to many other problems in a marriage, such as adultery, jealousy, having children outside of marriage and a combination of many reasons leading to conflicts that break up the marriage.

We married in 1985 after dating for several years. After getting married I knew that he had a relationship with another woman. He knew that girl on the farm. On Tet holiday, I suddenly saw him sitting on the bed with a 2–3-year-old child (boy). My husband is from the north. His family liked for us to have a son, while I gave birth of a daughter. So I thought that when I had a son, he will return, so I tried to be pregnant again. I heard him tell his brother that if I was pregnant this time, the other side (that girl) would give birth very soon later. I thought I would have a son to change my life. Then I gave up and did not know what to do because I had one more daughter. When I gave birth, he left and only returned after a week or half a month. When my daughter was 10 months, I stopped being with him because that girl gave birth to a son. My husband said that according to the custom, the north people had to have a son, while I have two daughters. He really wished to keep the relationships with both of us but I decided to break up. There was no way to be happy living in such circumstances, too much suffering and tears (Ms. NNT, Can Tho province, born in 1962, divorced in 1999).

The fourth reason for divorce is economic problems (Fig. 4). There is not a straightforward explanation for the fluctuating trend of economic reasons for divorce in Vietnam. The trend of increases and decreases of divorce due to economic difficulties showed the multifaceted nature of this reason. Before 2000, data showed that divorce due to economic difficulties was still present, but it was not high (i.e. 2% per year, equivalent to about 1,000 divorces each year). This trend is associated with the social transformation right after Renovation in 1986 including increased living standards, release of the modality of collective ownership, free trade and business, the end of the stamp subsidy policy and acceptance of better household economies, definitely created the general sense of social satisfaction and a strong priority to eradicate hunger and increase poverty reduction at both the family and social levels. Divorce due to economic reasons was therefore low on the list of necessities in the context that, as literature showed, all people were as poor as everyone else (Dang Reference Đặng2008; Nguyễn Reference Nguyễn1991) and only serious poverty and hardship led to family breakup at this time.

Figure 4. Percentage of divorce due to economic problems by total divorces in Vietnam, 1998–2017.

In the early 2000s, when Vietnam began promoting industrialization, modernization and urbanization, pressures from modern life such as the availability and wave of increasing costs of housing, employment, income and expenditure pressures in a competitive living environment had direct impacts on families, especially young ones, especially in urban areas. Economic reasons for divorce in the 2000s account for about 3–5% of the total divorces per year (Fig. 4). It was often associated with pressure caused by the stress of low income and high expenses, and the difficult balance between work and childcare by women, as well as individual psychological shock from rapid changes in economic conditions. For instance, new infrastructure and construction projects often bestowed valuable land compensation on families, which presented problems for families. Economic problems in turn lead to other marital problems such as the psychological pressure when family resources are no longer enough to maintain an expected standard of living. This kind of poor marriage quality increases family instability because the feelings of unhappiness or dissatisfaction with marriage are often followed by thoughts and behaviours that lead to divorce, as reported by the case studies. The case studies show that macro causes may translate into ancillary reasons for divorce. Similarly, a divorce can involve a combination of multiple reasons. For example, economic hardship can cause domestic violence, marital relationship conflicts and dissatisfaction or adultery.

My personality is different from his in terms of expenditure and attitude at work. He wanted to control my money so I felt not comfortable. I wanted to keep my own money I earned and be free to spend it on my needs. At the court, he asked for my forgiveness but I refused because I was hurt for a long time in such a marriage (Ms. TTT, born in 1973, married in 1993, divorced in 2004).

Divorce rates due to economic problems slightly decreased since the late 2000s and declined quickly to a stable proportion of 2% in recent years (Fig. 3) and was even lower in the South (Table 2), which might reflect the fact that not many couples divorce due to economic hardship now as well as the pressure in an increasing and stable economic development of the family and society. Case studies show that economic problems are associated with various marital problems such as the fading of love and tension.

I divorced in 2011 because we had economic difficulties. My husband was a school guard with a low salary while my salary as an elementary teacher was low, too. We had a child. In 2012, I met another man and had a child with him. I found out he was selfish because he left me with the house chores and money making. When the child was six years old, he left. Now I live with my two kids and just focus on working on rearing my children and not thinking of any other relationship (Ms. VKT, born in 1980, married in 2007, divorced in 2011, cohabited in 2012 and separated again in 2018).

My husband was heartless and he spent limited time with the family. He could not take care of the children, and the young children could not help me. The feeling I had was of being alone with so much pressure. The deepest hole was when my daughter was five months old. My mom asked me to give her my wedding gold gift that my mother-in- law gave me at the wedding in order to combine with my gold dowry to make it a big one. I took the gold to my mom and she said it looked a bit strange. She brought it to the gold shop and found out it was all fake. In the wedding my mother-in-law gave real gold. My mom was angry and asked my mother-in-law and she said she replaced the fake one behind my back because she needed money. I was so depressed and felt empty (Ms. PPTT, born in 1974, divorced in 2011, now living with her parents, having a son).

The fifth reason for divorce is adultery, which is considered as a reason for divorce in a modern individualistic society, is increasing (Fig. 5). The trend of adultery as a reason for divorce in last 20 years in Vietnam has fluctuated, but generally decreased slightly over the years as the registered reason to end the marriage. Up to the mid-2000s, about 6–7% of divorces were reported as due to extramarital relationships engaged in by one or both spouses. Over time, along with the modernization process, individuals may become more and more open about sex, love and happiness, resulting in higher autonomy in mate selection, which may help reducing the risk of looking for another partner. In addition, as divorce is more open, couples may hide this actual reason when registering the reason for divorce at the court in order to save face with their children, as well as in front of their formal and informal network. Adultery is shameful and still stigmatized and may even result in punishment at work for working people, especially in the public sector. In fact, by listing all conflicts actually happening in the marriage and then reflected in the divorce profile including the registered reason and marital problem shown in the reconciliation papers, adultery ranks the second among reasons for divorce in the South in the period 2010–2017 (Table 2) and ranks as the third highest cause of divorce in the North in the period 2000–2009 and extremely high in rural areas due to the conflict between individualism and patriarchal norms protecting the power of men (Tran Reference Tran Thi2014).

Figure 5. Percentage of divorce due to adultery by total divorces in Vietnam, 1998–2017.

Some men's attitude towards patriarchy changes slowly while women's wider viewpoint on gender equality increases due to government policies and media campaigns. The increasing economic position and reduction of the direct control of the family over migrant women restructure and reduce traditional gender roles as they shift from being unpaid housewives to becoming income earners. This type of change is likely to enhance women's independence and enhance their role in family decision-making, including divorce, as supported by case studies of the divorcees. The case studies show lots of divorce stories related to open love and extramarital sex engaged in by men due to the vestige of patriarchy in marriage, but women do not accept that.

I could not be pregnant for a long time and then suddenly I had a baby. But then I found out my husband had a concubine and left me alone. I then cohabited with another man and lived with him for 6 years, had a child with him until I found out he also had another wife. I stopped the relationship and asked him to return to his wife. I do not accept to be a second wife (Ms. TTXL, born in 1962, Khmer ethnic group, illiterate, married at 17 years old, had first child at 26 years old, divorced in 1993).

In addition, divorce may be due to one spouse engaging in some practices such as drug addiction, or being imprisoned or having disappeared or many other reasons related to social problems. These cases of divorce were high in the early 2000s (i.e. about one-third) and then decreased slightly to 12.07% in 2017 (Fig. 6). These divorces reflect the complicated perspectives of marital problems in a transforming society. For example, some women both married and unmarried were trafficked across the Chinese border and disappeared, leaving their husbands at home forced to divorce in order to remarry. Some people worked away from home and had no contact with their families for a long time, so people at home had to divorce to find new happiness. The social practices and problems such as drug addiction, gambling and alcoholism are also related to many other causes of family conflicts such as violence and economic hardship.

My business was good but I cannot manage my money, my ex-wife flew away. In general, as a man, I gave all my earned money to my wife. Unluckily my wife liked gambling and spent all my money in a casino. I knew nothing since I worked all day every day. I only knew one day when she lost all the money and sold our house to pay for her casino debt (Mr. NNP, born in 1964, married in 1990, three children, divorced in 2015).

Figure 6. Percentage of divorce due to social problems and distancing by total divorces in Vietnam, 1998–2017.

Finally, the most profound reason for divorce in Vietnam recently is divorce due to differences in lifestyle. In the first year the court allowed recording lifestyle difference as a reason of divorce in 2007, the proportion was 57.3% (equivalent to 35,091 divorces) and this category increased gradually to 80.6% (equivalent to 167,989 cases) in 2017 in the court register system (Fig. 7) and in the divorce profile (Table 2). Before 2007, the reasons for divorce were often recorded based on one party's “fault,” such as violence, adultery, economic hardship, failure to have children or addiction. It is a fact, although, that the elements of lifestyle difference or not being in love are often recorded as concrete alternative reasons such as differences in awareness, appearance and age. Since 2007, the divorce record-keeping system of the courts at all levels has supplemented the reason for divorce because of differences in lifestyle, which is not necessarily based on spousal “fault” in marriage. This shows more social openness and acceptance of divorce because it allows for a one-party divorce or confidential divorce due to the failure of love. In fact, the divorce data because of inappropriate living styles show a strong shift from traditional and old divorce to modern divorce.

Figure 7. Percentage of divorce due to lifestyle difference by total divorces in Vietnam, 2007–2017.

Source: The author calculates based on Annual Statistics of Vietnam People's Supreme Court (Figs. 1–7)

The nuanced expression of contradictory lifestyles can be reflected in personality, the way the couples treat their natal family and family-in-laws, or point of views and thoughts. These expressions are not contradictory conflicts that end marriage as quickly as other reasons, but wear out a couple's emotions and love, making them gradually no longer want to stick together. The quotations from some of the following divorce case studies show different stories about conflicts from lifestyle differences leading to divorce:

For the past three years, I have lived sadly, and we do not agree with each other. Sometimes I set up a plan to build up our family life but when put into practice, she is not serious. We lived together unhappily and kept arguing. Then we did not discuss anything to each other. We live on our own (Mr. D, divorced, two boys, born in 1959, divorced in 2016).

According to Vietnamese culture, in the first few years of getting married, couples often lived with husband's parents or sometimes with the wife's parents. Co-residence living arrangements cause complicated conflicts in terms of differences in lifestyles, work division and financial contributions and division.

My husband's family has ten people and we were eating and living together. Things got more complicated when some siblings-in-law got married and lived together in the home. For instance, I often had to clean all the dishes and washed while other daughters-in-law did nothing. Day by day I felt angry and tired (MS. NKL, born 1978, divorced in 2009).

After getting married, we lived in my parents' place because my parents' condition was good and their house was large. But my husband treated my parents badly in that he did not even say ‘hello’ to them when he met them. He treated my siblings badly, too. He felt guilty because he could not own a house. Our love was fading and we gradually felt nothing about each other. At court, he said nothing and the court ended and signed for the divorce in 15 minutes (Ms. NTN, born in 1965, divorced in 2005).

Employment opportunities also affect women's marriage decisions. The ability to advance in career has challenged and revolutionized the concept of the traditional male breadwinner. The prevalent double standards for women related to work, house chores and care giving work requires sharing of domestic work while some men are not ready for that due to their strongly held belief in patriarchal norms.

I want to improve our economic condition so I raised pigs. I had to feed them every day but my husband helped with nothing. Several times when I sold pigs to buy gold or something, he said that he should wear (gold) and then the gold disappeared. I worked very hard without his sharing. He thought house chores were not his business. When I asked for a divorce, the court invited him five or six times but he refused (to divorce) but I insisted. He still loves me now and we have a good relationship (Ms. VTKM, born in 1962, commune staff, leaders of some social organizations in the commune).

Lifestyle differences reveal the persistence of a male-centre family ideology in contemporary Vietnam, which allows “selfish” (not “individualistic”) behaviour of husbands. Regardless of a wife's significant role in family economic and care giving work, men with feudal and Confucian influences continue asking for the wife's obedience and show their inappropriate reactions in daily family life, as an in-depth interview revealed:

After being married for several months, I started feeling different. I tried to adapt to avoid quarrelling. Like other officials at that time, we lived in a room in a collective building assigned by our office. Each room was divided by a very thin bamboo mat partition. Another couple lived on the other side. They would laugh at us if we beat each other. This situation dragged on for 7–8 years. We separated once, and then reconciled, but conflicts started afterwards. We then separated for a second time before we officially divorced. She never stopped demanding more income even though I tried my best. I myself had a quite high income at that time, but it still did not meet her demands. I said to her I am not a cash printer at the bank (Mr. K, born in 1955, rural Ha Nam, divorced in 2012).

At the same time, lifestyle differences may indicate a change in the Vietnamese patriarchal culture that values men more than women. Accordingly, from the mentality of resignation, sacrifice and tolerance for the behaviour of her husband, women become less accepting of these old customs as the status of women rises during the modernization process. This is a story of Ms. Tr, who divorced due to a lifestyle conflict and economic troubles:

He is very arbitrary and bossy, with so many abnormal thoughts. He said he loved me, but he always showed that he thought he was more valuable and belonged to higher class. He looks down at me and disregards my values by saying such things as if I did not marry him, I would be a prostitute. Or that I was so lucky to marry him so I must behave well. In general, he always said things to hurt me and to look down on me (Ms. Tr, born in 1982, university educational level, counselling staff, Hanoi, divorced in 2011).

In-depth interviews of divorced people reveal that “lifestyle difference” sometimes hides the actual reasons, such as family conflicts or adultery. This happens because individuals tend to claim a neutral or convenient reason for dissolution of a marriage in a “modern” society where divorce has become easier. Since lifestyle differences are increasingly being considered the reason for a divorce, it could be a real reason. This means that Vietnamese people are becoming more “individual” in marriage behaviour. As divorce becomes socially easier, the rate of divorce for this kind of individual reason increases dramatically as can be seen in Figure 7.

Conclusion and discussion

This paper explored prevalence of and reasons for divorce, as a means to gain insight into changes in social norms and values in Vietnam during modernization. Divorce in Vietnam shows an increase in the complex transformation combining patriotism in war and reconstruction time; socialism in eliminating out-dated feudal ideology, forming and reshaping new stereotypes in marriage and the family; yet competing with feudalism and Confucianism which remain vestigial after a thousand years of blending into the social foundations in the feudal period.

The analysis contributes to the literature on reasons for divorce. Although divorces rooted in the feudal and Confucian system of marriage, such as domestic violence and polygyny, child and forced marriages, have shown a marked decline, showing progress in society, divorce due to childless marriage is significant in the context of the current limited welfare support for the informal sector. Old age security and care expectations are placed on children, which emphasizes the value of children to Vietnamese people. The persistence of this traditional reason demonstrates the complexity of modernization in family values. The economic reasons for divorce show a tension between work and the family, between income and expenditure and between social development and individual response in a transforming society. As such, modernization has engendered new reasons for divorce. Divorce is changing from a fault-based model to a more liberal one and people are moving from collective to individual styles of living in society with a dramatic increase in claims of “lifestyle differences” as the reason for divorces. The fact that the courts have recognized this reason demonstrates legal structural change following social and economic change.

Southern Vietnam is more influenced by the flexible and open marriage and family norms of other Southeast Asian societies (Yeung et al. Reference Yeung, Desai and Jones2018) and has higher income and lower participation of women in the labour market (GSO 2019) while Northern Vietnam is more influenced by the social norms and values of East Asia (Raymo et al. Reference Raymo, Park, Xie and Yeung2015). Yet, the two regions show similar trends in divorce prevalence and reasons, although the extent of modern reasoning is more pronounced in the South.

Socio-structural and legal changes under an increasingly widespread modernization process have caused individuals to adopt more liberal values towards marriage and the family. With material comforts vastly improved, people are no longer satisfied with marriages that fulfil the need to carry on the family line and merely require women to obey and sacrifice. Individualism has become one of the most influential factors affecting not only increased rates of divorce but also the reasons for divorce.