Introduction

Once a point of departure for millions of emigrants, Italy has become, at least since the mid-1970s, a destination country for a growing number of people arriving in or travelling through the peninsula. Patterns of migration to Italy originate from a wide variety of locations; they have significantly changed the social make-up of the country and made it the site of a very diverse multi-ethnic society.Footnote 1 This process has been accompanied by the reawakening of deep-seated social anxieties that testify to the fact that the more common construction of Italianness has been marked by the dovetailing of national identity, Catholicism and whiteness and by representations of gender and sexuality that were also implicated in various ways in the nation-building project. On the other hand, the resurfacing in the national consciousness of questions regarding identity brought about by the visibility of migration to Italy has also spurred a return to those cultural and historical conjunctions where the conception of a homogeneous Italy has been constructed and enforced, but also questioned, interrogated and taken to task. The ‘southern question’ certainly represents one of the most significant and consequential of these sites of construction/interrogation, and, from its first formulation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it has not ceased to shape in various ways the perception that many have of the South.Footnote 2

Throughout the long history of the Othering of the Italian South, notions about gender and sexuality have served an important ideological and biopolitical function. Research on gender history and on the history of sexuality in Italy has contributed significantly towards gaining a more nuanced understanding of processes of ‘Othering’ of the South in Europe and in Italy from the nineteenth century onwards. ‘Perversions’ and ‘abnormal’ sexual and gender behaviour were associated with those regions and parts of the world that were seen as inferior and backward. In the works of criminal anthropologists like Niceforo and Ferrero around the time of unification and in the following decades, ‘perversion’, ‘effeminacy’ and sexual immorality were increasingly associated with southern Italy and local gender and sexual identities and behaviours, like the femminiella in Naples or the idea, apparently quite common in some regions and social milieux of the South, that homosexuality was a normal part of male adolescents’ sexual maturation into proper adult heterosexuality, were seen as proof of degeneracy and of a North-South difference (Beccalossi Reference Beccalossi, Babini, Beccalossi and Riall2015, 190–191).

Ironically, later progressive historians of sexuality in the 1960s and 1970s also relied on a teleological view and linear model of sexuality in the construction of their accounts, usually positing a progression from sexual repression in the past to modern sexual liberation in the present. This is evident, for example, in Giovanni Dall'Orto's discussion of what he calls ‘Mediterranean homosexuality’ (Dall'Orto Reference Dall'Orto and Dynes1990). Dall'Orto, a prominent gay activist, constructs the Mediterranean homosexual as a residual ‘constitutive opposite’ of the ‘modern’, northern gay man, who is to be the political subject of gay liberation. In setting up this binary opposition, Dall'Orto reiterates the teleological, linear model of earlier commentators on southern sexuality, de facto excluding more local and less normative forms of expression of gender and sexuality from the political horizon. It might very well be that there are in the South local forms of expression, codification and embodiments of gender and sexuality, but they are certainly not to be considered as a less developed stage of the modern homosexual. Even more recent and supposedly less partisan accounts of non-heterosexual subjectivities, such as the large sociological study by Marzio Barbagli and Asher Colombo (Reference Barbagli and Colombo2007), reproduce this teleological view and problematic idea of ‘sexual modernity’, by positing a complete break between the ‘modern homosexual’ of today and the plural configurations of non-heterosexual subjectivities of a recent and less recent past.Footnote 3 This framework sees sexuality as a single issue and constructs a backward/modern binary which has a long genealogy.

This binary is probably felt with higher degrees of intensity today in discourses that oppose modern Western secular society and what Jin Haritaworn calls the image of the ‘homophobic Muslim’. Haritaworn underlines how the homophobic Muslim has become ‘a new folk devil who joins an older archive of crime, violence, patriarchy’ (Reference Haritaworn2015, 3), in a context where ‘the innocent and respectable queer subject who is worthy of intimacy, protection and safe space is born … against a backdrop of war, imperial rescue, violent borders, criminalization’ (Reference Haritaworn2015, 3). This process is part of what Jasbir Puar, and others after her, have called homonationalism (Puar Reference Puar2007), a conceptual frame developed in order to understand ‘the complexities of how “acceptance” and “tolerance” for gay and lesbian subjects have become a barometer by which the right to and capacity for national sovereignty is evaluated’ (Puar Reference Puar2013, 336). When looking at the specificities of the Italian case, one could at first glance be quite doubtful of the convenience of speaking of homonationalism in Italy, in the absence of an institutional discourse that proclaims itself to be anti-homophobic and anti-transphobic and to want to defend LGBT subjects against sexism and homophobia, seen as forces external to the nation. Nonetheless, some scholars and activists have noticed in the Italian case, in absentia of an institutional endorsement, a sort of drive towards a nationalist inclusion from below, that is, coming directly from LGBT subjects and from LGBT organisations and mainstream political groups (Acquistapace et al. Reference Acquistapace, Arfini, De Vivo, Ferrante, Polizzi and Zappino2016). On the occasion of the recent passing of the law on same-sex civil unions in Italy (the so called legge Cirinnà) in 2016, for example, the campaigns and rhetorical strategies put forward by the country's mainstream LGBT associations have shown a subtle but evident degree of nationalism and racism, which can be seen from an analysis of the posters and documents produced by these groups for the major demonstrations that took place at the time in various Italian cities (Acquistapace et al. Reference Acquistapace, Arfini, De Vivo, Ferrante, Polizzi and Zappino2016). The same can be said of many of the campaigns of the mainstream LGBT groups in Italy, at least in the last decade, which draw on problematic notions of ‘civilisation’ or on contradictory anti-discriminatory messages (De Vivo and Dufour Reference De Vivo, Dufour, Marchetti, Mascat and Perilli2012; Colpani Reference Colpani and Giuliani2015). This is consistent with a neoliberal strategy that tends to include LGBT subjects and to grant them some rights only in so far as they are willing to enter into a nationalist framework that can be easily used in order to legitimate longstanding ideas of ‘advanced’ versus ‘backward’ cultures and hence justify the implementation of political measures based on those assumptions, especially regarding migration and foreigners, but also the economy.

In this article, I look at how contemporary Italian cinema registers and confronts the mutual articulation and construction of discourses on gender and sexuality and discourses on national and regional identity with respect to the Italian South, and I will do so by focusing on one specific case study, Emma Dante's Via Castellana Bandiera (2013). Numerous scholars in the fields of contemporary Italian literature and contemporary Italian cinema have noticed in the last 30 years an increasing centrality, in both novels and films, of themes related to cultural interaction and intercultural exchange.Footnote 4 It is no coincidence then, that at least since the 1990s, when the issue of migration to Italy started becoming more and more central in the national imagination, artistic production from or on Italy appears to be preoccupied also with the history of the Italian South and with its status vis-à-vis the nation.Footnote 5 Also, many recent films that focus on southern Italy, on southern and/or migrant characters, and on the South as the border of Europe in the context of global migration, employ representations of queerness in ways that are quite pivotal, and that can be looked at in connection with both homonationalist discourses and with the long history of the sexual politics of the Othering of the Italian South and of the global South.Footnote 6 Emma Dante's Via Castellana Bandiera stands out among these contemporary productions for the very situated and at the same time evocative ways in which it weaves together questions of local and national belonging and questions of sexual and gender identity. The film explores the imaginary related to queerness and its connection to questions of migration and nationhood in order to offer a complex representation of southernness that takes into account the interaction of these multiple discourses at a subjective level. In my analysis of Dante's film I describe how the film confronts or complicates the discourses of the South as backward through the exploration of ethnicity, sexuality and gender. I will also show how the film positions itself with respect to the discourse that removes the queer subject from the political and cultural horizon of the South while dovetailing it with modernity, with ‘civilisation’ (this is the word most used in the campaigns at the time of the legge Cirinnà and before), and with the North. In order to do so, I will focus on the use of multilingualism and translation as a way to achieve a complex character construction, on the strategies of representation of the South in the text and the politics of genre which the film enacts, and on the ways in which the film engages with questions of mobility and migration.

Via Castellana Bandiera

Via Castellana Bandiera is the first feature film by the established theatre director Emma Dante. Born in Palermo and raised in Catania and Palermo, Dante first pursued a career as an actress, attending the Silvio D'Amico academy in Rome and working with renowned personalities of Italian theatre, such as Cesare Ronconi and Gabriele Vacis. At the end of the 1990s, Dante made the decision to become a director in her own right and to move back to the South. In 1999, in Palermo, she founded the theatre company Sud Costa Occidentale, a name that makes clear the commitment to put ‘the South at the centre: our language, our stories, but also this name specifies which South: the west coast of Sicily’Footnote 7 (Porcheddu Reference Porcheddu2006, 42), and hence the attempt to encompass both a general and a more localised notion of the South. The film, produced by a variety of institutional and private partners, was adapted by Dante and the writers Giorgio Vasta and Licia Eminenti from a novel of the same name published by Dante in Reference Dante2008. The action in the film takes place in Palermo, mostly in the street that gives the film its title, and in a time span encompassing roughly half a day and a night. The plot revolves around two distinct sets of characters: Rosa and Clara, the ‘modern’ lesbian couple, and the Calafiore family, inhabitants of one of the poorest neighbourhoods of the city. Rosa, a native of Palermo who left the city years earlier, and Clara, her non-Sicilian partner, are travelling to Sicily by car on a hot summer's day, arriving in Palermo from Rome to attend a friend's wedding. While the two are having an argument and are almost on the verge of breaking up, they lose their way and find themselves in a narrow street in the north-western periphery of Palermo: via Castellana Bandiera. Here they find themselves head-to-head with another car, bursting at the seams with the Calafiore family, and driven by an older woman, Samira. At this point, neither Rosa nor Samira is willing to budge and to let the other car pass through the narrow road. They both turn off their engines and wait. Eyeing each other across their dusty windshields, the two women engage in a sort of duel to see who will give up first and give way to the other. While the rest of the Calafiore family get out of the car and go home, Samira decides to stay in the car waiting for Rosa to lose her patience and eventually let her pass. Similarly, Clara does not see the point of the stand-off and decides to go and look for food, leaving Rosa alone in her car. Rosa and Samira spend the night challenging each other across the short distance that divides them, engaged in a silent dialogue: they both refuse, emphatically and defiantly, to eat and drink, and they both refuse to listen to the people around them and to their advice, completely absorbed by the duel taking place between them.

The conclusion of the narrative moves at a faster pace, after both Rosa and Samira, very late at night, seem to be falling asleep in their cars. Shortly after Rosa wakes up, at the crack of dawn, it becomes clear that Samira is not sleeping. She is in fact dead in the locked car. Samira's death ends the stand-off: while the Calafiore family and other inhabitants of the street try to force open Samira's car, Clara and Rosa reverse theirs and finally drive away. Samira's vehicle starts sliding down the road faster and faster, with her body in it, while the Calafiore family tries desperately but ineffectively to stop it. The last long scene consists of a still frame of via Castellana Bandiera with the inhabitants of the street running through it and then exiting the frame as if chasing Samira's car, while a song by the composers Fratelli Macaluso, the only piece of music in the whole film, plays in the background.

Character construction through gender and linguistics

Rosa's character is quite interesting when looked at in connection with discourses of the South as backward and the equation between modernity and LGBT subjectivity. Rosa is in fact a native of Palermo, which she left many years before the start of the narrative and from which she has tried to distance herself physically and emotionally. The very fact of being back in her city of origin is for Rosa a reason for distress and emotional conflict. The opening dialogue between Rosa and Clara foregrounds the unresolved nature of Rosa's relationship with her city, her mother, whom she does not want to see (the film hints at the fact that Rosa's mother might be unaware or disapproving of her homosexuality), and her southern belonging in general. Rosa's upward social mobility has followed a south to north geographical trajectory that she is not willing to retrace in reverse. The motivations behind her decision to engage in the duel with Samira once she finds herself in via Castellana Bandiera are not easy to make out in any straightforward way. The film certainly suggests that the confrontation with Samira becomes for Rosa a confrontation with her own self. This is evident in the many points at which the camera, hand-held behind Rosa (giving the spectators the illusion of being somehow seated in the back of the car) shows Samira through the two windshields dividing the women, while also showing, in the rear-view mirror, the reflection of Rosa's eyes looking at Samira. The insistence on different versions of this shot suggests, through the symbolism of the mirror and the reflection, the theme of identity/alterity (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figures 1 and 2. Rosa (Emma Dante) and Samira (Elena Cotta) looking at each other (00.34.26; 00.51.22)

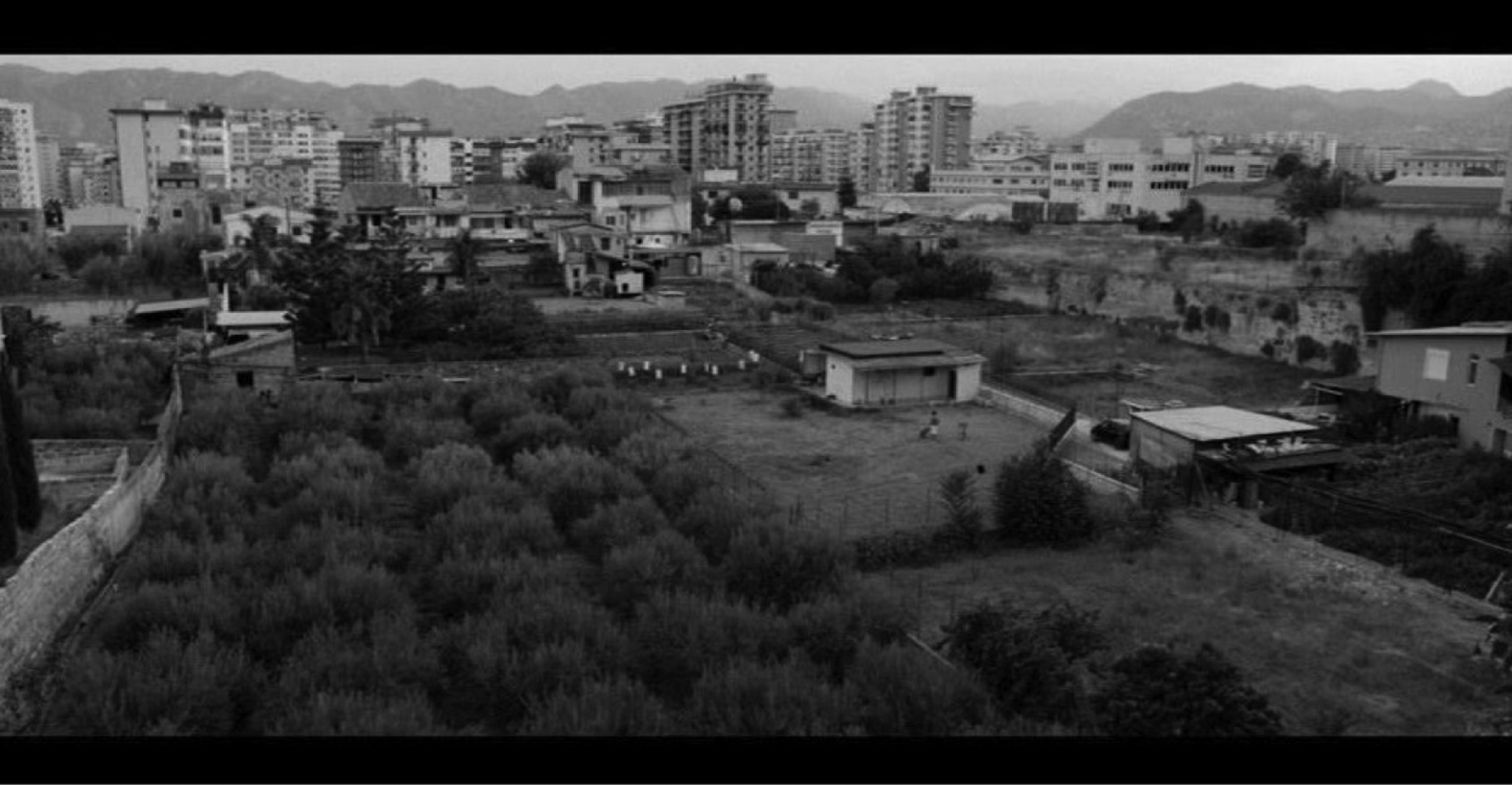

Certainly, the confrontation Rosa has with herself has a lot to do with her unresolved, complex and conflicted relationship with her southern origins. This comes to the fore in a scene later in the film at the end of the night, when Rosa and Clara have a moment of reconciliation and tenderness in their car. Rosa tells Clara that she has already been in that part of the city: as a child, she used to wander off to what was then almost countryside, devoid of buildings and houses, in order to calm herself when she was angry (see Figure 3). The film thus alludes to the history of the unruly growth of the peripheries of major southern cities like Palermo in the 1960s and 1970s, when the high level of internal migration from the country and from smaller cities to the major urban centres determined the fast and unsatisfactorily planned creation of new neighbourhoods, which soon fell into urban decay and where a new urban proletariat lived in dire conditions (Bevilacqua Reference Bevilacqua2005, 113–117). This explanation serves as an illustration of Rosa's motivations in engaging in the duel with Samira and it bridges the private and the public, the individual and the collective, the centre and the periphery, by inserting the history of internal migration into the core of the individual's concerns. The present degradation of the western periphery of Palermo (for which Rosa possibly blames the inhabitants of these neighbourhoods), the memory of how the place used to be, maybe the sense of a commonality of a shared space, somehow prevents Rosa from letting go of what could be read only as a petty row over right of way on the roads.

Figure 3. The view from the end of the narrow street in Via Castellana Bandiera (00.35.22)

This reawakened and conflictual sense of belonging to the South that Rosa's character has to come to terms with is signalled with even more force by the use of linguistic code-switching in what constitutes a moment of denouement of the narrative of the duel. The inhabitants of the street call Rosa ‘tischi-toschi’, the derogatory term used in the dialect of Palermo to refer to people who speak Italian or to southern people who speak Italian without a southern accent; in one of the initial scenes, she is also shown addressing a man who is speaking to her in dialect, saying in Italian that she ‘doesn't understand a thing’. Later on, almost at the end of the night, Rosa looks at Samira, who has fallen asleep in the car in front of her. Rosa wakes Samira up by flashing her with her headlights and pushing her car with her front bumper. When Samira wakes up, Rosa, as if she was speaking to the older woman, speaks to herself in the dialect from Palermo: ‘Io sugnu chiù corna dura di tia … capisti?’ (‘I am more stubborn than you … understand?’).

Southernness, queering and belonging

Rosa's southern belonging is, then, a queering and troubling element, something that stands in the way of attaining and fashioning for herself a homosexual identity inflected by neoliberal values and thus defined by ‘a privatized, depoliticized gay culture anchored in domesticity and consumption’ (Duggan Reference Duggan2003, 50), as Lisa Duggan describes one aspect of the sexual politics of neoliberalism that she terms new homonormativity. How the film hints towards this queering element that southern belongings seem to be able to affect can also be seen in another scene where the use of translation is particularly revealing. Clara has decided to go looking for food and Nicolò, Samira's grandson, has offered to take her to the city on his moped. The theme of translation is introduced at the beginning of the scene, when Nicolò starts speaking Palermitan to Clara and then switches to Italian when she says she does not understand. While waiting for their food to be prepared, Clara and Nicolò take a stroll on a street overlooking the city's port and have a conversation where Clara reveals to Nicolò that she is Rosa's girlfriend.

Nicolò: Are you with someone?

Clara: Yes.

Nicolò: Is he handsome?

Clara: Nice legs and a nice ass … and even better tits! Come on … don't make that face! (she pushes him jokingly). I am with Rosa, my girlfriend.

Nicolò: Ah!…so you are an ‘arrusa’…

Clara: What am I?

Nicolò: ‘Arrusa’…‘frocia’…

Clara: More ‘arrusa’ than ‘frocia’. (They both laugh)

[50:20–50:51]

In a recent article that analyses the linguistic and cultural translation of the word ‘queer’ in the Italian context, Michela Baldo underlines how many attempts at reclaiming the abject character of the word ‘queer’ in Italy, especially in activist circles, have been made through ‘words which have a similar connotation derived from the repertoires of regional languages’ (Baldo Reference Baldo2017). Baldo reconstructs the history of this linguistic strategy to disprove the idea of the use of the term in the Italian context as simply an example of Anglophone cultural hegemonic domination. On the contrary, such a linguistic/cultural translation is for Baldo, who follows here Luise von Flotow's terminology, an example of the feminist translational strategy of hijacking and of translation as political action. In the dialogue between Clara and Nicolò, we can identify a similar strategy of appropriation/adaptation of the regional word ‘arrusa’ (roughly meaning ‘queer’ in the dialect from Palermo), which, elsewhere in the film, is openly used as an insult (by Saro against Samira). When presented with the Italian translation ‘frocia’, Clara decides to self-define and identify herself as ‘arrusa’ rather than ‘frocia’. Baldo's considerations in regard to the presence of the word ‘queer’ in these activist translations, i.e. that the term indicates ‘a surplus of subjectivation, something which interrogates’ more solidified and normative identities, can be applied here to Clara's choice of ‘arrusa’ over ‘frocia’. Moreover, Clara's character is not a southerner herself, hence the term can hardly be taken as signalling simply an identitarian, purely descriptive move but, rather, to indicate that ‘surplus of subjectivation’ to which Baldo refers, a way of distancing herself from the contemporary mechanisms of the neoliberal and nationalist valorisation of LGBT subjects in contemporary Italy and transnationally.

At the same time, the film does not define southernness in terms of idealised and essentialised openness to diversity. Our attention is drawn to the gender hierarchy that informs the social structure of via Castellana Bandiera from the very beginning of the narrative and in many different ways after that. The authoritarian, violent and exploitative behaviour of many of the male characters towards women finds a powerful formulation in the idea of the betting pool organised by the men of the Calafiore family. While Rosa and Samira are engaged in their duel, the Calafiore men, together with the Neapolitan ‘magliaro’ Filippo Mangiapane, try to turn the situation to their profit by organising a betting pool among the neighbours on who will back off first. They plan to convince their neighbours to bet on Samira resisting the longest, but plot to persuade the old woman to eventually let Rosa pass through so they can cash in on their bets. Their plan is destined to backfire, as Samira will stubbornly refuse to comply with what her family urges her to do. We are also filled in on Samira's back story of exploitation and marginalisation in a scene with comedic undertones when, at the beginning of the stand-off, the women of via Castellana Bandiera sneak into Rosa's car to relate her opponent's story and try to convince her to give up. Yet, Samira is without doubt not presented in any victimised way in this scene or in the film. On the contrary, she is shown to be a woman who has an almost mythical reputation for stubbornness, a strong will and independence. Her role becomes almost an extended metaphor or an allegory. Samira almost never speaks throughout the whole narrative. This choice amplifies her importance in the collective imagination of the street and the allegorical function of the character. More than once Samira is called ‘cana ca un canusci patruni’ (‘a bitch with no owner’), a proverbial expression that seems to encapsulate her reputation and her cipher as a character. Such an association is reinforced when she is first introduced in the narrative: in the long initial sequence, Samira is shown feeding some stray dogs in the cemetery where her daughter is buried, letting them roam freely on her daughter's tomb and using the flowerbeds at the side of the grave as bowls for them to drink from; moreover, in this initial part of the film, Samira is always shot from the back or from the side, with her hair covering her face and eyes, in a style reminiscent of the tradition of Italian Horror film. When she is first shot frontally, the camera takes the point of view of Saro who suddenly sees her up at the top of a high road overlooking the beach, standing on a wall that says ‘forza palermo’ (‘Go Palermo’) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Samira's first appearance in Via Castellana Bandiera (00.10.28)

Samira is an allegory for the troubling effect of southern belonging, and she is also an allegory of foreignness and alterity in general. Her unruly nature is more than once explained by her being ethnically Albanian: as the audience is told first by Saro and later in the aforementioned scene with the ladies of the street in Rosa's car, Samira is an Arbëreshë woman from Piana degli Albanesi, a town not very far from Palermo, which was founded by Albanian emigrants fleeing Turkish invasion in the fifteenth century. Samira only seems to answer her grandson when he speaks to her in Arbëresh and the few lines she pronounces, possibly as a ghost, are spoken in Arbëresh. Like Medea, unpredictable, indomitable and identified by her place of origin, admired, feared and pitied by the chorus in Euripedes’ play, Samira seems to elicit the same reactions in the inhabitants of via Castellana Bandiera. Her exit from the narrative closely resembles Medea's flight from the Corinthian stage aboard the chariot of the sun. Like Medea, Samira is also a mother, and the film aptly constructs a subtext that frames the relationship between Rosa, a daughter estranged from her mother, and Samira, a mother who has lost her daughter, as a mother-daughter relationship. This is a feature that would easily and profitably lend itself to a reading of the text informed by the feminist theory of sexual difference.Footnote 8

Samira's character can thus be read as an allegory for quite a vast, even vague, range of themes. While this characteristic is a way through which the film attains a high degree of complexity and multi-layered signification, it might, at the same time, take the text onto ethically shaky ground. As the more perceptive reviewers have noted, in fact, despite the larger-than-life role attributed to Samira, the film does not succeed in ‘getting under her skin’ (Weissberg Reference Weissberg2013). Elena Cotta herself, who won the Coppa Volpi at the Venice film festival for her interpretation of Samira, has said in an interview that she defines her role as ‘the antagonist: the antagonist is a pretext’ (Televisionet 2013). Samira can be read as a pretext for Rosa's inner journey and transformation, for her battling and coming to terms with her southern belonging, with her mother, with her infancy. All in all, the film engages only very briefly with Samira's ethnic background, with her history of internal migration or with an excavation of her motivations for engaging in the standoff, and it eliminates her at the end.

Nonetheless, even if Via Castellana Bandiera can be said to perform a certain silencing of the ‘different woman’, this silencing, and an evocative narrative reflection on subalternity, seems to be overtly thematised in the film. In Via Castellana Bandiera, Samira's silence is a deliberate choice of the character, a form of resistance, which she adopts for her own purposes and which creates a great deal of trouble for all the other characters. If, in Spivak's formulation, the subaltern woman's experience is constantly appropriated by groups and constituencies whose interests and political purposes are quite distant from her own, in a way that nonetheless saturates her space of self-determination (Spivak Reference Spivak, Nelson and Grossberg1988), Samira's silence can be legitimately read as a strategy to resist such appropriations and reclaim agency. Moreover, the non-realistic codes of representation the film adopts, especially in relation to Samira's character, her reappearance as a ghost and her evocative exit from the scene of the film, endow the character with elements of power and agency.

Borders and genres: subverting the western

As is evident from the previous discussion, the film foregrounds and explores various kinds of borders existing simultaneously and blurring the boundaries of different spatialities (North and South, centre and periphery, local, national and global, city and country), of temporalities (modernity and tradition, past and present, the linear and progressive time of the neoliberal nation and the simultaneous temporalities of transnationalism), and of supposedly monolithic identities (class, gender, regional and national belonging, ethnicity, sexuality). These borders materialise and assemble themselves spatially in via Castellana Bandiera, at the periphery of one of the major southern Italian cities, where Rosa, the modern lesbian invested in a process of vertical class and ethnic mobility, and Samira, the ethnically marked and lower-class older woman, come to stand one in front of the other, their opposition and the immobility they force on each other resonating with discourses and practices regulating various other kinds of mobility or congealing of identities. The film constructs the South itself as a border-zone, a concept that, as Saskia Sassen writes, ‘entails opening up a line (represented or experienced as dividing two mutually exclusive zones) into a border zone that demands its own theorization and empirical specification’ (Sassen Reference Sassen2000). The first parts of the film seem to be combined through a consistent use of practices of estrangement in all the different sections that introduce the main characters. Samira is first shown in the cemetery where her daughter is buried, feeding some stray dogs: the familiar setting of the cemetery is rendered strangely unfamiliar by the decaying state of the tombs and graves, some of which seem to have been reduced to piles of rubble, and by the free and unhindered roaming of the dogs on the tombs and in the space of the cemetery. The already liminal space of the graveyard, a place inhabited by both the living and the dead, is presented in an even more defamiliarised way that calls into question hierarchies of human/animal, an impression confirmed at a later moment when Nicolò is seen eating a stolen bread roll, given to him by Samira, of the same kind she previously fed to the dogs. Moreover, the film verges on the liminal poetic of the gothic (Aguirre Reference Aguirre, Benito and Manzanas2006) in one of the final scenes when Samira, who has possibly already died in her car, reappears in the narrative as a ghost, entering her old house, carefully folding her grandson's clothes while gently reproaching him in Arbëresh for his untidiness, and then lying on her bed to rest. A similar argument can be made about the way the text introduces Rosa's character. Rosa and Clara are first shown travelling on the highway approaching Palermo; the camera lingers on an old decaying church erected not far from the highway: the juxtaposition of the fast and modern highway on which Rosa and Clara's car is travelling and the old church, a remnant from a past still present, creates a striking contrast, blurring the boundaries of progressive temporality and of clear-cut, autonomous notions of past and present. This consistent and functionally diversified use of the estrangement effect all throughout this introductory part of the film establishes the South as a liminal space from the very beginning of the narrative.

The status of the South as a frontier and a border is also central to the section of the narrative occupied by the duel between Rosa and Samira. The open citation the text makes of the spaghetti western genre in this part of the film is geared towards a deterritorialisation of the ‘spectacular masculinity’ (Neale Reference Neale1983, 16) that is a landmark of that genre. According to Maggie Günsberg, the spaghetti western ‘is especially concerned with the borderline between different genders, sexualities and races. It both investigates and polices the boundaries of masculinity against the incursions of femininity and non-whiteness’ (Günsberg Reference Günsberg2005). Via Castellana Bandiera engages with and expands on the representational repertoire of the spaghetti western, (which, according to Neale, is already marked by a fetishistic character that ambiguously reveals and at the same time conceals the eroticisation of the male body), in a subversive way that is in line with its attempt at queering the South as a border. In the central part of the narrative of the duel, Samira and Rosa are shown in their car eyeing each other with hostility; the camera goes from a close-up of Samira's face to one of Rosa's face. When one of the women of the Calafiore family brings food to both of them, leaving a serving of pasta in each of their cars, first Samira and then Rosa get out of their cars and throw the food behind the wall that delimits the street. They then stand in front of each other, their legs open and their arms stiff, assuming the posture of the traditional western showdown. The text references classic westerns very closely, first framing the two figures at a distance in their surroundings, then narrowing the frame progressively to a medium shot, to a close-up of their faces and then to the extreme close-ups of their eyes typical of the spaghetti western. But instead of drawing out their guns at the moment of maximum tension, Samira and Rosa resort to a different weapon: while standing immobile in front of Rosa and looking at her defiantly, Samira empties her bladder and lets her urine drip down her legs onto the ground, where it forms a pool. The camera follows the stream of urine and then enlarges its frame to show a squatting Rosa who, without breaking eye contact with Samira, is also urinating on the dirt. As scholars who have engaged with the representation of urine and urination in contemporary art have underlined, the use or representation of bodily fluids in art is often a way to ‘oust or blank out patriarchal images’ (Minissale Reference Minissale2015, 71) by disrupting and subverting habits or expectations of a viewer or spectator who is familiar with the conventions of a certain genre.

In the spaghetti western, the fetishistic character of the eroticisation of the male body, although present, is ambiguously deflected by the narrative, which ensures that ‘we see male bodies stylised and fragmented by close-ups, but our look is not direct, it is heavily mediated by the looks of the characters involved’ in the duel (Neale Reference Neale1983, 14). In Via Castellana Bandiera, not only are the characters who look and are looked at both female, but their presentation is not eroticised in any classical way. Moreover, the surprising outcome of their confrontation, which substitutes the shoot-out with urination, puts both the female characters in the diegesis and the extradiegetic spectator in the position of the fetishist, thus somehow circumventing a visual pleasure premised on identification with binary and complementary sexual difference, with both patriarchal masculinity or normative femininity. Through this subversive reference to the spaghetti western, Via Castellana Bandiera redefines the space of the frontier, which in the spaghetti western is mostly constructed as an anxiously homosocial space, as a space for the exploration and playing out of female perversion and queer desire.

Although the film does not engage directly with the theme of contemporary migration to Italy, its narrative revolves around questions of mobility and the relationships among different social groups at the border: it thus creates a sort of frame of resonance with today's events and can be said to be preoccupied with them. This comes to the fore with great clarity at the end of the film. Late at night, after the showdown between Rosa and Samira and shortly before Samira's death, a distant shot of via Castellana Bandiera with the two cars positioned one in front of the other reveals how the street, which was too narrow to allow the two cars to pass through at the same time, has actually become much larger. In the morning, the street has become larger still. Such a metaphorical conclusion prompts in the viewer a series of open-ended reflections on who can and cannot move, on how the mobility of certain social groups seems to be predicated on the immobility of other groups within discursive frameworks that posit these marginal groups one against the other and that depict them as homogeneous and mutually exclusive. Via Castellana Bandiera thus effectively complicates mainstream ideas of migration, often seen only as immigration, and uses a different frame in which to raise questions about where and how cultures, languages, ethnicities, and identities meet. By connecting migration to questions of multiculturalism, multilingualism, southernness, and sexuality, the film queers the imaginary related to the southern border and is able to explore the working of borders at many different levels.

Conclusion: mobility, migration, southernness

The increasing centrality, in both novels and films, of themes related to cultural interaction and intercultural exchange represents one of the most prominent features of recent Italian literature and cinema. This shift certainly reflects the changes that migration to Italy has brought about in the social fabric of the country. As Jennifer Burns has noted in her study of the literary production of first-generation migrant writers, the fact that many ‘fully’ Italian writers gravitate towards themes of mobility and migration signals the fact that ‘migration, the postcolonial, and non-European cultures more broadly are an increasingly central, coherent, and historically situated figure of the Italian cultural imagination’ (Burns Reference Burns2013, 203). Burns's observation on contemporary literary production can be said to be valid for cinematic production as well. The analysis of Via Castellana Bandiera shows how an exploration of notions of southernness is also gaining a new centrality. The external Other coming to the fore on the national stage evokes and brings back the memory of internal otherness and ignites processes of comparison, parallelism, and a consideration not only of resemblances and similarities but also of moments of contact and interaction between the Italian South and other Souths. Dante's film refers to the history of marginalisation of the region and takes to task the dominant representation of it; as the analysis of the multilingual character of the film shows, the text complicates the dominant representation of the South through a subtle and poignant use of different languages (Sicilian dialect, standard Italian, Arbëresh) in order to achieve a complex character construction and through the emphasis given in the narrative to significant moments of translation. The subversion of the western genre, especially through the queering of the imaginary of the frontier which is central in the genre, can also be seen as a way to destabilise commonplace ideas of the South. This is also achieved through focusing on mobility and referencing the history of emigration from the South and migration to the South. The indirect engagement with new migration to Italy, the evocative connection which the film establishes among different histories of migration, is also central to the way in which the text explores the contemporary construction of sexual identity and its imbrication with issues regarding national and regional belonging and national and regional identity construction. The focus on mobility and migration is thus a way to reflect on how different identities are constructed, mobilised and played against each other in the neoliberal context, and to challenge the homonationalist construction of LGBT identities in contemporary Italy. The attention to the complex way in which issues of gender and sexuality interact with issues of race/ethnicity, migration, national and regional identity construction which informs the text thus demonstrates how a new material and cultural process of reinvention of the South premised on different tenets is underway, after the process of what philosopher Paul B. Preciado, although not in relation directly to Italy, has evocatively called ‘the invention of the south’ (Preciado Reference Preciado2017).Footnote 9 This reimagining of the Italian South explores the South-to-South connections of the Italian South, focuses on the interaction and imbrication among different axes of subjectivity (such as sexuality, gender and race/ethnicity), and in so doing significantly contributes to complicating and diversifying the landscape of contemporary Italian film.

Note on contributor

Goffredo Polizzi holds a PhD in Italian Studies from the joint programme of Warwick and Monash (Monash-Warwick Alliance). He has published various articles addressing questions of postcolonialism, transnationalism, constructions of gender, race and sexuality in contemporary Italian literature and film. He is a founding member of CRAAAZI, Centro di Ricerca e Archivio Autonomo transfemminista queer ‘Alessandro Zijno’ (craaazi.org).