Introduction

A substantial body of literature holds that “institutions do not travel well” [Machinea Reference Machinea2005: 4; Rodrik Reference Rodrik2007: 41; Drezner Reference Drezner2009: 190; Rafiqui Reference Rafiqui2009: 347; Lambach and Debiel Reference Lambach, Debiel, Cavelty and Mauer2010: 160; Morlino Reference Morlino2016: 32], and are particularly ill-disposed toward long-distance travel [Berkowitz et al. Reference Berkowitz2003; Roland Reference Roland2004; Seidler Reference Seidler2014], with the Latin American experience frequently being invoked by way of example. After all, the region bears the scars of a number of dubious imports including French legal codes that by all accounts work better at home than abroad [Merryman Reference Merryman1996; Beck et al. Reference Beck2003; Berkowitz et al. Reference Paryono2003; LaPorta et al. Reference LaPorta2008; Kogut Reference Kogut and Kogut2012]; presidential regimes that are purportedly prone to gridlock in the United States and golpes south of the border [Linz Reference Linz1990; Misztal Reference Misztal1992; Helmke Reference Helmke2010; cf. Lipset Reference Lipset1994]; and a Washington Consensus—codified by a British expatriate, no less [Edwards Reference Edwards2010: 65]—that has proven disappointing to supporters as well as critics [Williamson 1997; Offe Reference Offe2000; Przeworski Reference Przeworski2004; Centeno and Cohen 2012; Connell and Dados 2014]. Observers of the region have therefore abandoned the idea of “blueprints” and “best practices” [Rodrik Reference Rodrik2000: 14; Evans Reference Evans2004: 30] for aphorisms like “one size doesn’t fit all” [Pritchett and Woolcock Reference Pritchett and Woolcock2002: 3], “context matters” [Portes Reference Portes, Wood and Roberts2005: 38], and “Latin American solutions to Latin American problems” [Tanner Reference Tanner2008: 260; Ignatieff Reference Ignatieff2014: 465; Bertucci Reference Bertucci2015: 108; Escanho Reference Escanho2015: 2].

The latter slogan, in particular, echoes the call for “southern solutions to southern problems” [UNESCO 2013: 9; see also UNCTAD 2010: 4; Zhou Reference Zhou2010: 4; UNDP 2011: 420; Thomas Reference Thomas2013: 1; ILO 2013a: 11; WHO 2014: 11] that has been gaining support in the donor community and which is invoked to explain the diffusion of special economic zones and conditional cash transfers in Asia and Africa. “Born out of similar development contexts and sometimes even familiar cultural background,” explain Xiaojun Grace Wang and Shams Banihani of the United Nations Development Programme, “these southern solutions often prove to be more relevant” [Wang and Banihani Reference Wang and Banihani2016: 15] than northern imports that are rigid, costly, and/or ill-suited to their new surroundings.

Latin American vocational training institutions (VTIs) have been portrayed as another southern solution [UNDP 2009: 167; Amorim et al. Reference Amorim2013: 5; ILO 2013b: 18]. After all, the “Latin American model” [Middleton et al. Reference Middleton1991: 46; Gasskov Reference Gasskov1994: 57-58; Carton and Tawil Reference Carton and Tawil1997: 24; Jäger and Bührer Reference Jäger and Bührer2000: 15; Galhardi Reference Galhardi2002: 1; Ramirez Guerrero Reference Ramírez2002: 56; de Ferranti et al. Reference De Ferranti2003: 112; Jacinto Reference Jacinto2008: 4/36] of payroll tax-financed, stakeholder-governed training was allegedly developed by Brazil’s National Industrial Training Service (Serviço Nacional de Aprendizagem Industrial or SENAI) in the early 1940s, when the US was distracted by World War II [Sherman Reference Sherman2000: 69]. It was then disseminated to the rest of the region over the course of the next half century, when import-substituting industrialization placed a premium on the development of a skilled, manual labor force [Schmitter Reference Schmitter1971: 184; Howes Reference Howes1975: 195; Castro Reference Castro1999: 44-45; Márquez Reference Márquez2001: 9; Jacinto Reference Jacinto2008: 4-36; Carrillo and Neto Reference Carrillo and Dequech Neto2013: 88]. Finally, it was responsible for the education and training of millions of Latin American workers [Middleton et al. Reference Middleton1991: 46; Casanova Reference Casanova2013: 14] including, most famously, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva [French Reference French2010: 141], who would go from metalworker to union activist to President of Brazil. In fact, Michel Carton and Sobhi Tawil have described the Latin American model as an “innovative and endogenous” alternative in a region that has traditionally been “polarized between European and American influences,” thereby endorsing the idea that institutions that are indigenous to their regions of adoption are superior to their foreign or extra-regional counterparts [Carton and Tawil Reference Carton and Tawil1997: 24].

Are southern solutions really superior to their northern counterparts? I address the question by revisiting the “neglected transnational history” [Penny Reference Penny2013: 363; see also Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2005; Rinke Reference Rinke2013; Manz Reference Manz2014; Cassidy Reference Cassidy2015] of Germans in 20th century Latin America and find not only that Brazil adopted key features of SENAI from Germany during the war but that direct ties to Germany—forged by immigrants, investors, and diplomats in the prewar era—constitute a key predictor of the model’s diffusion to the rest of the region after the war. While countries like Argentina, Colombia, and Venezuela had relatively close connections to prewar Germany, and therefore established training institutions like SENAI in the 1950s, their neighbors had less exposure to German ideas and institutions, and therefore maintained an “incentive-driven” [Márquez Reference Márquez2001: 8] approach to training into the 1980s and beyond. The results suggest that institutional importation is less the discrete event or outcome that theories like “legal origins” [LaPorta et al. Reference LaPorta2008] and “varieties of capitalism” [Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001; Schneider Reference Schneider2013] have, at their worst, implied [Schmidt Reference Schmidt2009; Fast Reference Fast2016; cf. Jackson and Deeg Reference Jackson and Deeg2008: 555] but an ongoing process that, first, entails translation, adaptation, and at times obfuscation by importers as well as exporters; and, second, is facilitated by “mobile professionals” [Favell Reference Favell2003: 399; see also Fechter and Walsh Reference Fechter and Walsh2010]—including skilled immigrants and investors, their descendants, and diplomats—from both importing and exporting countries in transnational “contact zones” [see Pratt Reference Pratt1991; Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2007: 31; Pence and Zimmerman Reference Pence and Zimmerman2012: 495; Manz Reference Manz2014: 4; Penny and Rinke Reference Penny and Rinke2015: 181; and Fortwengel and Jackson 2016 on contact zones involving Germans in particular].

I have divided the rest of the paper into four principal sections. Section 1 discusses the alleged obstacles to institutional transfer, in general, and to the transfer of the German model of vocational education and training, in particular, including cultural as well as material incongruity between Germany and Latin America. Section 2 presents evidence that the roots of Latin American VTIs are nonetheless to be found in Germany, rather than Brazil, and identifies three distinct transmission paths: imitation by Latin American professionals of German origin and descent in the years prior to the Second World War; propagation by West German donors in the postwar era; and adaptation by policymakers and employers—who not only had distinct needs, capacities, and cultures but received further support from German firms and donors—in the more recent era of globalization. Section 3 introduces quantitative data on the diffusion of VTIs in Latin America and finds descriptive evidence that they were indeed established more rapidly in countries that had closer ties to Germany in the early and mid-20th century. And Section 4 concludes that the relative success of the so-called Latin American model speaks neither to the superiority of indigenous institutions in the Global South nor to the advisability of “institutional engineering” [Przeworski Reference Przeworski2004: 166] by great powers but to the roles of (i) mobile professionals in the public as well as private sectors in importing and adapting institutions to the needs of their local environments; and (ii) comparative historical sociologists in illuminating the—often deliberately—hidden histories of late developing countries more generally.

Intellectual context

The literature on institutional transfer is marked by a profound skepticism concerning the prospects for cross-cultural learning and mimicry. While modernizers like Peter the Great, Kemal Atatürk, and the architects of the Meiji Restoration have been portrayed as inveterate importers of western models and methods [Lewis Reference Lewis1961; Gerschenkron Reference Gerschenkron1962; Dore Reference Dore1973; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1979; Westney Reference Westney1982; Goldman Reference Goldman2006], they have simultaneously been dismissed as exceptions to a rule acknowledged by dozens of historians and social scientists.Footnote 1 “Countries are simply too different, economically, legally, politically, and culturally to make fruitful policy borrowing a serious possibility,” in the words of Martin De Jong and his colleagues [De Jong et al. Reference De Jong2007: 5]. “If they differ too much from one another, even ambitious policy actors in the recipient country who actively attempt such an adoption, will run into incompatibility and incongruence which make the transfer impossible or even deleterious.”Footnote 2

The sources of incompatibility and incongruence are cultural as well as material, and Alejandro Portes portrays the long-neglected concept of social roles as the key to their interpretation and analysis [Portes Reference Portes2006: 243]. Consider, for example, the differences between formally similar roles in fundamentally different societies. “That of ‘policeman’ may entail, in less developed societies, the expectation to compensate paltry wages with bribe-taking, a legitimate preference for kin and friends over strangers in the discharge of duties, and skills that extend no further than using firearms and readily clubbing civilians at the first sign of trouble” [Portes Reference Portes2006: 243]. When “modernizers” try to professionalize the police officer’s role, therefore, they will run into opposition not only from the officers and their kin, who have come to expect and—perhaps depend upon—payoffs and preferential treatment, but from public officials and their allies, who have come to treat the police force less as a public service provider than as their personal militia.

The risks are compounded not only when institutions are transferred from “like-to-unlike” [De Jong and Stoter Reference De Jong and Stoter2009: 321] societies but when they are “tightly coupled” [Orton and Weick Reference Orton and Weick1990] to broader institutions. “While in the loosely coupled areas of law a transfer is comparably easy to accomplish,” in the words of Gunther Teubner, “the resistance to change is high when law is tightly coupled in binding arrangements to other social processes” [Teubner Reference Teubner, Hall and Soskice2001: 426]. Examples would include commercial laws that are linked to health, science, technology, and culture. “It is in their close links to different social worlds,” he continues, “that we can see why legal institutions resist transfer in various ways” [Teubner Reference Teubner, Hall and Soskice2001: 431].

Nor is commercial law unique, for the German model of vocational education provides a no less compelling example of a “tightly coupled” institution [see, e.g., Hannan et al. Reference Hannan1996: 16-17; Hemerijck and Manow Reference Hemerijck, Manow, Ebbinhaus and Manow2003: 229; Estévez-Abe Reference Estévez-Abe2005: 26; Trampusch Reference Trampusch2008: 12] that is by most accounts ill-disposed to transfer. After all, the “dual” system pioneered in Imperial Germany and polished in the postwar era is designed to address the fact that unfettered markets tend to underprovide skills, in general, and “partially transferable” skills that are “valued by some but not all employers” [Robalino et al. Reference Robalino and Almeida2012: 51], in particular. Employers worry that the returns to training are elusive in a world of worker mobility, and thus limit their efforts to the cultivation of firm-specific skills that are not portable across the labor market. Workers worry that their efforts to fill the gap by paying for their own training will be devalued by employers or rendered redundant over time, and thus fail to make up the difference. And the low-level equilibrium that results demands a collective response by “firms, intermediaries, and the state” [Busemeyer and Trampusch Reference Busemeyer, Trampusch, Busemeyer and Trampusch2012: 4].

The German response entails a combination of “school-based learning with practical firm-based training” [Thelen Reference Thelen2007: 248; see also Herrigel Reference Herrigel1996: 52], and thus demands the cooperation of educators, employers, workers, and their respective associations—not to mention the public officials who oversee and co-finance their efforts to ensure that German firms and workers have the skills they need to keep up with their foreign rivals. “In short,” explains Wade Jacoby, “the system depends on both a dynamic private sector and an articulated network of other organizations and associations in order to function properly” [Jacoby Reference Jacoby2000: 191; see also Culpepper 2003].Footnote 3

In fact, the German system has taken on more stakeholders over time. Kathleen Thelen notes that the original German model emerged when an “independent artisanal sector” was “endowed with the rights to regulate training and to certify skills” [Thelen Reference Thelen2004: 39], in part to provide a conservative counterweight to the country’s increasingly radical labor movement, in the late 19th century. Large-scale industry came on board in the run-up to the Second World War, she argues, when the Nazis built “a more unified national system for apprenticeship training” [ibid.: 239] on the backs of both the original artisanal system and organizational and technical innovations that had been developed by the manufacturing sector in the Weimar era. While the war itself posed a number of challenges, to be sure, the system was reconstituted “along lines that built directly on pre-war institutions” [ibid.: 240] in the postwar era, by granting the artisanal and industrial sectors formal responsibility for plant-based vocational training in the 1950s [ibid.: 241], and incorporating the labor movement in 1969, when the Grand Coalition government of the Social Democrats and the Christian Democrats at long last assigned responsibility for in-plant training to “tripartite boards at the national and state levels” [Thelen Reference Thelen2004: 242; as well as page 262 on the “high degree of continuity” between the prewar and postwar models]. By the late 20th century, therefore, the dual system depended on artisans, manufacturers, unions, and their interlocutors in the public sector—who played a key role in “tipping the scales toward collectivism” [Thelen and Busemeyer Reference Thelen, Busemeyer, Busemeyer and Trampusch2012: 88] whenever individual stakeholders would threaten to defect from the de facto coalition.

According to Jacoby, East Germany lacked the necessary “patterns of associationalism and intergroup cooperation” [Jacoby Reference Jacoby2000: 207], and thus proved inhospitable to the dual system in the wake of reunification. But the former German Democratic Republic is not alone. Others note that China, France, the United Kingdom, Indonesia, South Korea, and a number of African countries have tried to import the dual system to little or no avail [Paryono Reference Paryono2005: 46]. Contemporary observers doubt that the German model would work “well in the United States, a very different economy and society” [Hockenos Reference Hockenos2017; see also Hanushek Reference Hanushek2017]. And Francis Fukuyama warns that the German model is part of “a broader education system that would not be easy to break apart into pieces for export” and ultimately depends on “social and cultural traditions that are unique to central Europe” [Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama1995: 237].Footnote 4

The literature on vocational education thus constitutes a microcosm of the broader literature on institutional transfer. Experts claim that institutions do not travel well, and are particularly ill-suited to long-distance travel. Their claims have been applied to German training institutions in particular [Drake Reference Drake1994: 155; Blossfeld and Stockmann 1998-1999: 16; Allen Reference Allen2004: 1151; UNIDO 2017: 114]. And Latin Americans have therefore been portrayed as the fortunate beneficiaries of a “Southern-grown” [Amorim et al. Reference Amorim2013: 9] alternative developed and exported by Brazil [Amorim et al. Reference Amorim2013: 35-36; see also Caballero Tamayo Reference Caballero Tamayo1969; Carton and Tawil Reference Carton and Tawil1997; Trollo Reference Trollo2012]. While the German model is classroom-based, and involves simultaneous apprenticeships at participating firms, the Latin American alternative is “center-based” [Dougherty Reference Dougherty1989: 14; Ducci Reference Ducci1991: 118; Ibarrarán and Rosas Shady Reference Ibarrarán and Rosas Shady2009: 204-205], and prioritizes pre-employment training at public institutions that are financed by payroll taxes and governed by tripartite boards [Ramírez Guerrero Reference Ramírez2002: 57; see also Whalley and Ziderman Reference Whalley and Ziderman1990: 378; Gasskov Reference Gasskov1994: 57-58; Galhardi Reference Galhardi2002: 6; de Ferranti et al. Reference De Ferranti2003: 112]. “Being relatively independent from the government and being funded from a levy on the payroll,” argues Claudio de Moura Castro, “most of these institutions are quite robust and affluent” [Castro Reference Castro2008: 3]. They are also close to employers and are correspondingly able to evaluate and meet their needs for both pre-employment and—when necessary and available—in-service training.

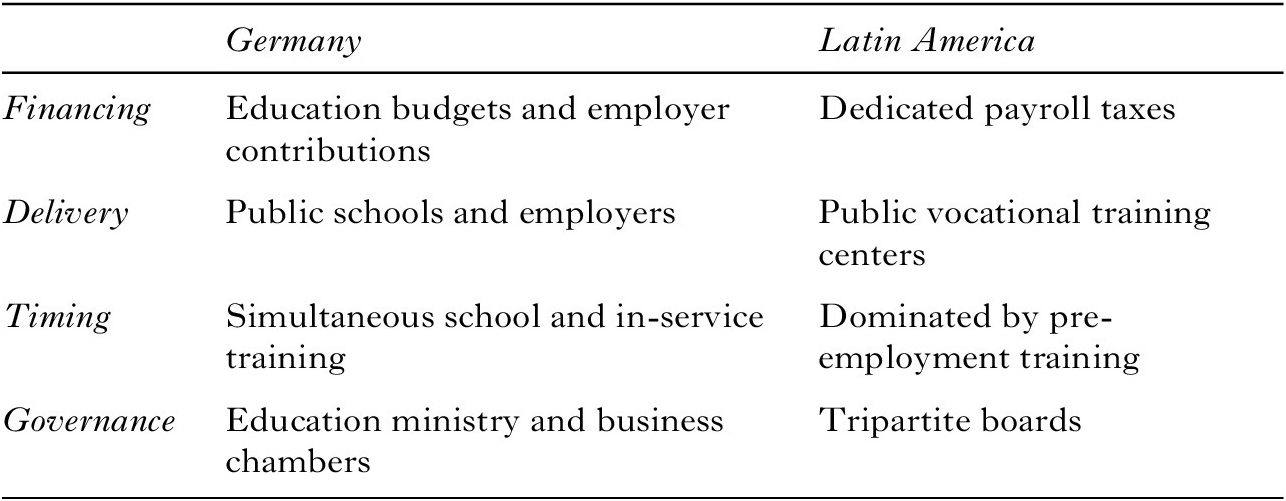

Table 1 distills the principal differences between the contemporary German model and the “soft or light Dual System” [Castro Reference Castro2009: 15] found in Latin America in terms of four key dimensions: the funding, delivery, timing, and governance of training.

Table 1 German and Latin American approaches to vocational education and training.

The table leaves out some important details. For instance, the Germans have been known to use the threat of payroll taxes to compel employer contributions when they were not otherwise forthcoming [Harhoff and Kane Reference Harhoff and Kane1997: 193; Thelen Reference Thelen2007: 254]. Latin American VTIs have at times facilitated in-service as well as pre-employment training [World Bank 1991: 46]. And Brazilian VTIs are exceptional in Latin America insofar as they are run not by tripartite boards but by trade associations closer to the original German model [Galhardi Reference Galhardi2002: 9; Ramírez Guerrero Reference Ramírez2002: 57], perhaps due to their precocious establishment before Germany’s postwar reforms. But the basic portrait painted by the table is accurate: While the German model is “heavily voluntarist” [Thelen Reference Thelen2007: 254] in orientation, and places the social partners in the driver’s seat, the “Latin American model” [Whalley and Ziderman Reference Whalley and Ziderman1990: 378; World Bank 1991: 46; Gasskov Reference Gasskov1994: 57; Atchoarena Reference Atchoarena1996: 31; Galhardi Reference Galhardi2002: 6; de Ferranti et al. Reference De Ferranti2003: 112] is compulsory in nature and driven—if not dominated—by the public sector.

In short, Latin American governments have addressed the free rider problem that bedevils skill formation by taxing employers and workers in an effort to pay for vocational training, and giving their representatives input into the allocation of the payments. The programs thereby created tend to improve the likelihood and quality of employment at the individual level [Jimenez et al. Reference Jimenez1989; Ibarrarán and Rosas Shady Reference Ibarrarán and Rosas Shady2009; Jaramillo Reference Jaramillo2013] and are broadly popular. Table 2 includes data on the working age population, the number of participants in vocational education and training (VET) programs, the percentage of youth and working-age adults participating, the absolute number of apprentices, and the number of apprentices per 1,000 employed individuals for 12 Latin American countries in 2016.

Table 2 Vocational education and training in Latin America, 2016

Sources: OIT-CINTERFOR 2017; World Bank 2020.

While apprenticeships are for the most part limited to Brazil and Colombia, and nowhere approach Germany’s 39 apprentices per 1,000 employed individuals, overall participation in VET programs is quite high—ranging from 12% of the working-age population in Colombia, to less than 1% in Bolivia, to approximately 4% in the median country. Youth participation is much higher: an estimated 7% of the Latin American population between the ages of 15 and 24 [Vargas Zúñiga Reference Vargas Zúñiga2017: 11]. And VET programs have fueled the growth of key sectors in a number of Latin American countries, including automobiles in Brazil [Weinstein Reference Weinstein1996: 257-8; Ramalho and Santana Reference Ramalho and Santana2002: 761-762], apparel and footwear in the Dominican Republic [Schrank Reference Schrank2011: 8; Hertel Reference Hertel2019 108-109], and information technology in Costa Rica [Nelson 2009: 81].

The point, however, is neither to exaggerate the success nor to downplay the variety of the region’s vocational training institutions. While they have occasionally been subject to rigorous evaluations that reveal positive impacts on job quality and quantity [Ibarrarán and Rosas Shady Reference Ibarrarán and Rosas Shady2009; Ibarrarán et al. Reference Ibarrarán2019], they have at times been poorly managed or had trouble anticipating the demand for skilled labor [Middleton and Ziderman Reference Middleton and Ziderman1997: 8; Castro Reference Castro1998: 1]. But the very best examples—including not only SENAI in Brazil but SENA (Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje) in Colombia and INA (Instituto Nacional de Aprendizaje) in Costa Rica—are by all accounts “model institutions, with ample resources to allow them to offer the very best training” [Castro Reference Castro2008: 3].Footnote 5 I will discuss their roles and roots in the next section.

The German roots of Latin American training

Opponents of imported institutions take great pride in the success of the Latin American VTIs. Insofar as they are based on a Brazilian template, after all, the “S&I institutions” [Castro Reference Castro2007: 10]—so-called because their names almost invariably begin with an “S” or an “I”—underscore not only the limits to institutional importation but the potential for indigenous innovation [UNDP 2009: 167; Amorim et al. Reference Amorim2013: 5; ILO 2013b: 18], and the S&I institutions deviate from the German model in several key respects including their funding, delivery, and oversight [Eichorst et al. Reference Eichorst2012: 20]. But their originality and distinctiveness are at best partial, for the founders of SENAI in the 1940s included Brazilian engineers of German origin or descent and, not least of all, Weltanschauung [Weinstein Reference Weinstein1996: 255]; the funders of SENAI’s “clones” [Castro Reference Castro1998: 2] in the postwar period included German aid administrators and foundations [Stockmann Reference Stockmann1999]; and the adaptations being undertaken by the clones today are modeled upon—and in many cases supported by—their German counterparts. I will elaborate and offer examples of each mechanism in the next three subsections.

From dual to school: German immigrants and the origins of vocational education in Brazil

German influence over Brazilian VET anticipated the founding of SENAI by at least one generation, for Teutonic immigrants to Brazil portrayed themselves as “paragons of industriousness” [Cassidy Reference Cassidy2015: 2] in the 19th century; their self-portrait was in large measure embraced by local officials; and by the dawn of the 20th century their ideas had assumed a prominent position in the country’s public (and publicly financed) technical schools. Take, for example, the Gewerbeschule and the Instituto Parobé in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, home to a large population of German immigrants. While the former conducted classes in German, the latter offered classes in Portuguese but boasted German instructors and a curriculum developed by a headmaster of German descent, João Lüderitz, on the basis of a number of visits to Germany and neighboring countries [Lima Reference Lima2000]. In fact, Daniela de Campos holds that upon his return to Brazil practical training assumed pride of place in the curriculum. “Students produced goods for the market, guaranteeing the institute, the masters, and themselves a supplemental income,” she explains [Campos Reference Campos2013: 9; my translation; see also Howes Reference Howes1975: 197]. “Lüderitz believed that industrialization was essential for learning, for it would allow the student to come into contact with the factory environment.”

Nor was Rio Grande do Sul unique. A Swiss engineer by the name of Roberto Mange began to offer courses for railroad mechanics in São Paulo in the 1920s, traveled to Germany to learn the latest techniques in 1929, and eventually opened a highly regarded school in São Paulo. “The courses themselves, taught by special instructors, utilized the ‘methodical series’ approach to training perfected in Germany whereby apprentices begin with the simplest process or piece, repeat the task until perfected, then move in a highly regimented fashion to more and more complicated tasks” [Weinstein Reference Weinstein1990: 390].Footnote 6 While they offered an alternative model of worker training, and thus proved influential over time, his efforts made no more than a dent in the growing demand for skilled labor, and by the mid-1930s, therefore, President Getúlio Vargas had appointed a commission to explore alternatives.

The commission’s members included not only Mange and several other Paulista educators but Rodolpho Fuchs, a student of Lüderitz and Nazi sympathizer who would return from Germany in 1938 to wax enthusiastic about the country’s apprenticeship system [Weinstein Reference Weinstein1990: 391; Pronko Reference Pronko2003: 68; Cunha Reference Cunha2012: 386]. Whereas the commission as a whole would therefore concern itself with skill formation in the narrow sense, Fuchs would portray apprenticeship as “a vehicle for discipline, social control, and worker integration into the state-directed project for national development” [Weinstein Reference Weinstein1990: 392; see also Weinstein Reference Weinstein1996: 88] more generally, and therefore advocate firm-based training for all male workers in Brazil [Weinstein Reference Weinstein1996: 87; Weinstein Reference Weinstein, French and James1997: 80; Pronko Reference Pronko2003: 134].

In other words, Fuchs openly advocated Brazil’s embracing of the dual system. He praised both in-plant apprenticeships and their “voluntary” financing by employers in Germany. He traced their success not only to the policies of the Nazis but to the practices they had inherited from their predecessors. And he nonetheless predicted that efforts to adopt similar policies in Brazil would be met with massive resistance from recalcitrant employers [Cunha Reference Cunha2012: 389].

His prediction would soon be confirmed, moreover, for the Paulista industrialists worried that Fuchs was exaggerating their demand for skilled labor and convinced Vargas to design SENAI with an eye toward training no more than 15% of the incoming industrial labor force in 1942. While Fuchs would therefore accuse the president of placing “the needs of the national economy” above “the needs of Brazilian youth” [Weinstein Reference Weinstein1996: 99], and express disdain for the new program’s structure, his “observations on training in Nazi Germany and his call for close cooperation between training organs and industry undoubtedly influenced subsequent policy.” Employers “have played the preponderant role in decision-making, in designing the institutional framework of the system, and in implementing VET programs” [Assumpção-Rodrigues Reference Assumpção-Rodrigues2013: 18] in Brazil, and apprenticeships have been part of SENAI’s programming “from the beginning” [Castro Reference Castro2009: 15; see also Wilson Reference Wilson1993: 275].

In fact, John Middleton and Terri Demsky of the World Bank have portrayed “linkages” between firms and training authorities as perhaps the “most important” aspect of SENAI’s success, and note that they have “been part of the SENAI tradition since the 1940s” [Middleton and Demsky Reference Middleton and Demsky1988: 73], when the agency was born and Lüderitz and Mange assumed the directorships of the national and São Paulo offices respectively. Employers offered SENAI input and SENAI took their needs into account. “Combined with expanding employment and increasingly effective enterprise management,” they continue, “this helped create a supportive ‘ethos’ in which the needs of employers were taken seriously and reflected in training plans and curricula” [Middleton and Demsky, Reference Middleton and Demsky1988: 73; see also Howes Reference Howes1975: 212 and Weinstein Reference Weinstein1996: 115-116, on Lüderitz and Mange’s roles in SENAI].

Nor are Middleton and Demsky alone in their assessment. Jörg Meyer-Stamer noted that SENAI offered two to three year-long training courses on request and on-site in the late 1990s, when almost half of all training occurred “on the firm’s premises” [Meyer-Stamer Reference Meyer-Stamer1997: 303]. And a number of observers have identified intense collaboration in the auto industry, where SENAI has worked with both multinational firms (e.g., Mercedes-Benz, Volkswagen) and their suppliers in an effort to impart transferable skills and inhibit free-riding among stakeholders [Ramalho and Santana Reference Ramalho and Santana2002: 761-762; see also Findlay Reference Findlay1984: 208; Wolfe Reference Wolfe2010: 242; Ferreira Reference Ferreira2016: 247; as well as Busemeyer and Trampusch Reference Busemeyer, Trampusch, Busemeyer and Trampusch2012 on collective skill formation more generally].

But the German legacy went beyond the realm of policy, or the ethos of employer involvement, to include the ethos of manual production itself. According to Castro, Mange set the intellectual agenda at SENAI in the 1940s and instilled German artisanal values that would persist for the next half century [Castro Reference Castro2002: 296; see also Castro Reference Castro2000: 3]. His partners in the private sector were “influenced by German ideas” [Klein and Luna Reference Klein and Vidal Luna2017: 113] as well. And both the Brazilian and German models therefore trace their roots to an “apprentice tradition” [Castro and Alfthan Reference Castro and Alfthan1992: 7-9] that not only facilitates coordination among key stakeholders but tends to shelter vocational education from “prejudices against manual occupations” [ibid.: 9] that are simultaneously prevalent in public schools and a threat to the non-cognitive underpinnings of skill formation. “Unless the ethos of the school is conducive to this non-cognitive development,” explains Castro, “everything else is doomed to failure. Schools dominated by academic teachers (and their ethos) cannot convince their students that the trades they teach are serious endeavours” [Castro Reference Castro1995: 20; see also Weinstein Reference Weinstein1996, esp. Ch. 3; and Tomizaki Reference Tomizaki2008].

SENAI’s Teutonic roots are thus undeniable. It is hard to believe that the agency would have embraced the apprenticeship model in their absence, all the more so given the preponderant role of the US educational model in the region [Cunha Reference Cunha2012: 403-405]. But denial was not only a predictable response to the Vargas regime’s declaration of war on Germany in late 1942 but a systematic one. When the Ministry of Education began to recruit Swiss instructors in an effort to replace the now-discredited Germans, for example, they dispatched none other than Mange—who had already assumed the directorship of SENAI’s São Paulo office [Castro Reference Castro1995: 19]—as an emissary, and by 1943 the German connection had been deliberately forgotten [Cunha Reference Cunha2012: 393-399]. When SENAI joined forces with Mercedes-Benz to open a school for skilled autoworkers in 1957, therefore, they did so anonymously, leaving their name off the diplomas until at least the mid-1960s—and off the school itself until 1984 [Tomizaki Reference Tomizaki2008: 73-74].

German donors and the diffusion of vocational education in Latin America

The end of World War II ushered in a volatile new phase of German-Latin American relations. On the one hand, Germany entered the postwar era defeated, discredited, and divided. Every Latin American country but Chile had eventually joined the Allied Powers, and even Chile had broken diplomatic relations with Germany in 1943.Footnote 7 Germany therefore had a good deal of diplomatic work to do in the region. On the other hand, the war accelerated the pace of import-substituting industrialization [Hirschman Reference Hirschman1968] and, in so doing, induced demand for skilled labor. So the Germans suddenly found themselves with a diplomatic opportunity as well.

After all, Germany had earned a reputation for engineering and craftsmanship by building schools throughout the region during the Second Reich [von Gleich Reference Von Gleich1968: 23; Herwig Reference Herwig1986: 52], and it knew it could put that reputation to work by delivering technical assistance designed to help Latin American countries meet their needs for skilled labor in the postwar era. Between the mid-1950s and mid-1960s, therefore, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) helped develop 26 vocational schools in 14 Latin American countries and stipulated that they “be turned over to native administration after a suitable period of operation” [von Gleich Reference Von Gleich1968: 78].

The Escuela Técnica Colombo-Alemana (Colombian-German Technical School, or ETECA) offers an excellent example. The school was established by German donors in 1960 in an effort to train metalworkers in Barranquilla, and immediately earned a reputation for high quality pedagogy. While the Colombian National Training Service (Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje, or SENA) would assume legal responsibility for ETECA in 1965, in keeping with the letter of the donation and the spirit of “self-help” [von Gleich Reference Von Gleich1968: 78] common to German donors, the Colombians would continue to rely upon German engineers until 1970, when they would at long last recruit local instructors backed up by ad hoc consultants from Germany [SENA 1977: 77; Cuervo Reference Cuervo2010].

Germany’s effort to foster self-help among the Colombians worked, and by the mid-1980s the center would play host to representatives of more than a dozen Latin American countries and be portrayed as a veritable model of south-south collaboration [Cuervo and Steenwyk Reference Costa1986: 82]. But the autonomy of SENA’s efforts, and the corresponding depth of self-help, should not be exaggerated, for their visits were underwritten by German donors, among others, and thus served to underscore the persistent, if at times hidden, German foundations of the allegedly Latin American model of vocational training.

Nor is the example isolated. On the contrary, Germany has been supporting SENAI’s efforts to help SENATI build a Center for Environmental Technologies in Peru [GIZ 2013; ILO 2013b; SENAI 2012; SENATI 2013]; the National Professional Promotion Service (Servicio Nacional de Promoción Profesional, or SNPP) train middle managers in Paraguay [SENAI 2008: 49; Severo Reference Severo2012: 7]; and cognate institutions train thousands of workers in dozens of countries in Latin America annually [Amorim et al. Reference Amorim2013: 35; as well as Ducci Reference Ducci1997; Stockmann Reference Stockmann1999; Trollo Reference Trollo2012]. The German government has also joined forces with VTIs and German multinationals like Siemens and Bosch in their efforts to encourage the spread of new techniques and technologies (e.g., computerized manufacturing and Industry 4.0) in the Andean countries [SENATI Reference REVISTA2016; Revista SENATI Reference REVISTA2018].

The point, however, is not simply the breadth but the opacity of the German efforts. By portraying their interactions as examples of south-south cooperation, after all, Latin American VTIs not only take credit for ideas and activities that build on decades of bilateral and triangular German support [see, e.g., Carrillo and Neto Reference Carrillo and Dequech Neto2013: 88] but exaggerate the plausibility of purely southern solutions to world poverty.

German practices and their adaptation to Latin American reality

Of course, the opposite sin is no less costly. Institutions are not easily transferred, and the Latin American VTIs have not simply transplanted the German dual system into their native soils but have used institutions that are loosely modeled on their German (and Teutonic) forerunners to experiment with a variety of different delivery mechanisms. The pre-employment and in-service training they offer is therefore administered by private firms and third-party providers, as well as their own centers, and their institutional role is therefore better described as “provider-cum-regulator” than “provider.” For instance, SENA in Colombia, INA in Costa Rica, and INFOTEP in the Dominican Republic offer “accreditation programmes for third-party training services and in this way, incorporate into the training courses on offer up-to-date contents with the same quality as those applied by State-run vocational training institutes” [Casanova Reference Casanova2013: 14; see also Jaramillo Reference Jaramillo2013]. Other VTIs offer private firms with approved in-house training programs tax breaks or “train the trainers” [Aring et al. Reference Aring1996: 57] in an effort to keep their knowledge and skills up to date. And many have adapted the dual system to the tropics and subtropics by developing workarounds like the sequential, rather than simultaneous, provision of theoretical and practical training [Castro Reference Castro2007: 9].

According to the International Labour Office, the best known “combination models are those coming from Germany, Switzerland and Austria” [ILO CINTERFOR 2013: 73], and they have been adapted to the local context by VTIs like SENA, SENATI, SENAI, INA, and INFOTEP. But the S&I institutions have frequently had the direct support of German donors and consultants in doing so [see, e.g., Gallart et al. Reference Gallart2003; INSAFORP-AECI 2006; Castro Reference Castro2007; Araya Muñoz Reference Araya Muñoz2008], and their efforts thus speak less to the authenticity of the purportedly Latin American model of vocational education than to the persistent, as well as “overwhelming” [Castro Reference Castro2007: 3], influence of German educational ideas and institutions in the region.Footnote 8

INFOTEP provides an example of both the importance of German support and the adaptation of the dual system to the Latin American reality. After all, the Dominican VTI began to develop a dual training program with German financial and technical assistance in the mid-1980s, less than a decade after the country’s democratic transition, and graduated the first of more than 6,000 apprentices in 1990, when 53 industrial and automotive mechanics finished the program [Labarca Reference Labarca and Labarca1999: 308-10; see also Confederación Patronal de la República Dominicana 2001].

But the Dominicans immediately encountered four barriers that would necessitate adjustments to the German model. First, they discovered that small and mid-sized firms in the Dominican Republic lacked the financial and technical wherewithal to take on apprentices, and thus shifted their focus from the smaller firms that had been the backbone of the dual system in Germany [Thelen Reference Thelen2004] to their larger counterparts [Labarca Reference Labarca and Labarca1999: 330; and INFOTEP 2010: 140-143]. Second, they found that the larger firms were not interested in adolescent apprentices, and thus shifted their recruiting targets from 14-22 year olds to 16-25 year olds [cf. INFOTEP 2010: 60; INFOTEP 2012a: 15]. Third, they found that many of their recruits lacked basic literacy and numeracy, and thus developed compensatory programs in conjunction with the Ministry of Education [Labarca Reference Labarca and Labarca1999: 306-7]. And, finally, they realized that they lacked a critical mass of skilled workers to mentor apprentices, and thus created a complementary program to train master technicians for the job [Labarca Reference Labarca and Labarca1999: 310].Footnote 9

The result has been a dramatic expansion in participation and training. In fact, the dual program now graduates hundreds—rather than dozens—of apprentices a year in a large and growing array of specialties [Ministerio de Economía 2011: 161; INFOTEP 2012b: 55; Ministerio de Trabajo Reference Ministerio de Trabajo2012: 16; UNCTAD 2012: 36]. The vast majority wind up with desirable jobs in their chosen fields and recommend the program without reservation [Labarca Reference Labarca and Labarca1999: 309; INFOTEP 2012a: 36; INFOTEP 2012b: 56]. And the Dominican experience thus implies not only that the German model can indeed be broken down into discrete bits and pieces for export—contra Fukuyama––but that German donors have been central to the process.Footnote 10

Quantitative analysis

I have traced the roots of the Latin American approach to vocational education to Germany and identified three distinct transmission paths: imitation by Latin Americans of German origin or descent; propagation by German donors, diplomats, and investors; and adaptation by the former with the support of the latter. Did the German legacy leave a mark on the statistical record? I address the question by looking for a systematic relationship between Latin American attitudes toward Germany, on the one hand, and approaches to vocational education, on the other, with the help of event history models that have typically been used to evaluate “the effect of global events or linkages on the adoption of policies and institutional structures by nation-states” [Schneiberg and Clemens Reference Schneiberg and Clemens2006: 200]. However, I treat the results not as estimates of causal effects but as “relatively simple but rich and precise descriptions of patterns” [Berk Reference Berk2004: 244] in the data. If there is a causal interpretation of the results it must come from the full array of qualitative and quantitative data, as well as the theory behind them, and not the “magic” [Freedman Reference Freedman1987: 209] of the statistical estimates.

The population of interest includes all 18 independent and non-communist countries of Spanish and Portuguese speaking Latin America, and the event in question is the formation of a national vocational training institution [Ducci Reference Ducci1991, Annex 1]. The units of analysis are “country-years,” beginning in 1940 when Latin American polities are first believed to be “at risk” of establishing VTIs, and ending with the establishment of the Salvadoran Institute for Professional Training (Instituto Salvadoreño de Formación Profesional, or INSAFORP) in 1993. By 1993, every country in Latin America had established a national VTI, and the data are therefore uncensored.

German influence in Latin America derived from a combination of demographic, economic, and cultural factors [von Gleich Reference Von Gleich1968; Grabendorff Reference Grabendorff1993-1994; Penny Reference Penny2013], and data on most are at best incomplete.Footnote 11 But Albrecht von Gleich portrays the “order in which relations were broken off and war declared” as a reflection of the “attitude of the various Latin American countries toward Germany” [von Gleich Reference Von Gleich1968: 19] in the early 1940s. Von Gleich [1968: 23] and Glenn Penny note that German ties to Latin America “persisted in many ways through the radical political ruptures that dominate our historiography” [Penny Reference Penny2013: 365]. I therefore create an ordered ranking ranging from 1 (in the four countries that declared war on December 11, 1941) to 14 (in Chile, the lone neutral country).Footnote 12

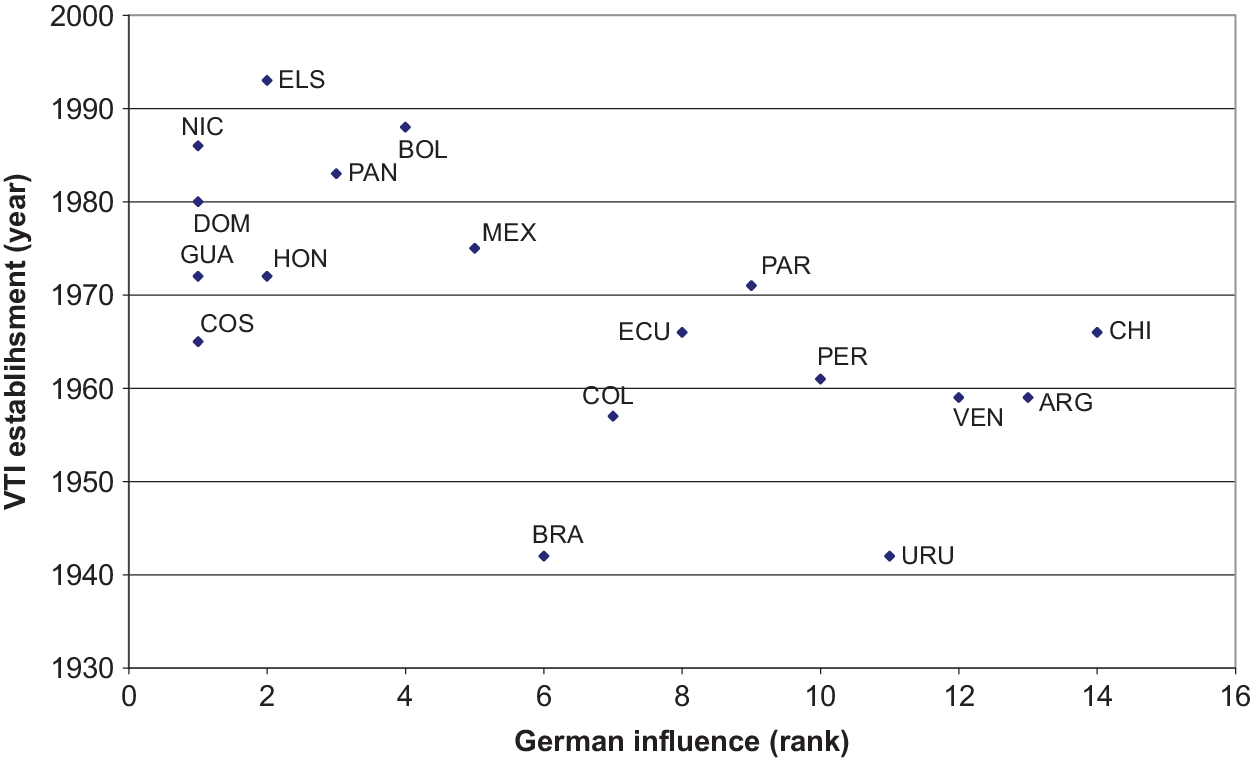

Figure 1 plots the year of VTI establishment by the indicator of German influence for the 18 Latin American countries and reveals a pronounced negative relationship. In fact, the bivariate correlation between the indicator of German influence and the year of VTI establishment is –0.61 (p < 0.01). But the possibility of spuriousness looms large, especially in light of the clustering of countries by size and region. While the larger, South American countries had closer ties to Germany, and would thus have been expected to deploy VTIs more rapidly in light of the historical record, they also industrialized faster, and therefore had more need for (and capacity to train) skilled labor. I therefore incorporate three control variables into the event history models.

Figure 1 VTI establishment by German influence

Industrialization

Gustavo Márquez holds that the S&I institutions were “part and parcel of the import substitution industrialization (ISI) strategy followed by most countries in the region until the early eighties” [Márquez Reference Márquez2001: 9; see also Weinstein Reference Weinstein1996; Castro Reference Castro1998], and I therefore control for the intensity of industrialization by including an indicator of iron and steel production per capita (in millions for ease of presentation) derived from the Correlates of War project data on National Material Capabilities [see Singer Reference Singer1987].

Education

Experts have long debated whether general education and vocational education are complements, substitutes, or unrelated to each other [see, e.g., Reference BowmanBowman 1988], and I therefore control for the breadth of general education—with no strong prior as to the direction of the relationship—by including an indicator of the adult literacy rate that is unfortunately available on a decennial rather than annual basis [Astorga et al. Reference Astorga2005].

Democratization

Regina Galhardi identifies an affinity between vocational education in Latin America and “the democratisation of the region and the emergence and strengthening of organised civil society” [Galhardi Reference Galhardi2002: 3; see also Busemeyer and Trampusch Reference Busemeyer, Trampusch, Busemeyer and Trampusch2012: 8], and I therefore control for the level of democracy with the Polity indicator obtained from the Polity IV project [Marshall and Jaggers Reference Marshall and Jaggers2013].Footnote 13

While the control variables are admittedly imperfect, they should capture differences in social and economic development between the region’s wealthier and poorer countries and ensure a more robust test of the effects of German influence. Table 3 includes summary statistics.

Table 3 Summary statistics

Summary statistics calculated on the basis of country-years prior to failure (or VTI establishment); n = 517.

The distributional assumptions underpinning most event history models are hard to evaluate in the absence of strong theory and large sample sizes [Blossfeld and Rohwer, Reference Blossfeld and Rohwer2002: 230], and I therefore analyze the data by means of an alternative—the Cox proportional hazard model—that makes fewer distributional assumptions and “dominates applied work in the social and life sciences” [Beck, Katz and Tucker, Reference Beck, Katz and Tucker1998: 1266].Footnote 14

By way of clarification, the model treats the probability of VTI establishment—given that none has been established previously—as a function of industrialization, education, democratization, and German influence. The results are contained in Table 4.

Table 4 Cox models of VTI establishment in 18 Latin American countries, 1940-1993

N of countries = 18; N of country-years = 535. Models are estimated with the Efron method for tied failures and robust standard errors; tests of the proportionality assumption are available from the author on request. Log pseudolikelihood = -30.598506; Wald chi2(4) = 12.08; Prob > chi2 = 0.0167.

German influence has a significant positive effect on VTI formation. A one-unit increase in the influence index is associated with an 18% increase in the hazard of VTI formation, and a standard deviation increase is associated with a doubling of the hazard, or the risk of VTI formation in a country that lacks a VTI, in the following year (i.e., 1.184.2 = 2.0). But the control variables fail to reach statistical significance and, in the case of industrialization, are incorrectly signed. The results are thus consistent with the idea that German influence is the key driver of vocational education in Latin America.Footnote 15

Conclusion

Latin American VTIs have been widely portrayed as “homegrown” [Trollo Reference Trollo2012] or “southern grown” [Kwak Reference Kwak2013: 47] success stories. But the evidence I have adduced suggests that their roots lie in Germany, and that they continue to receive support from their German forebears. Are celebratory portraits of the VTIs uniquely ahistorical? Unfortunately, the answer is “no,” for in their haste to “celebrate the local” [Kiely Reference Kiely2000: 1068; Bernstein Reference Bernstein2006: 59], development theorists have systematically ignored or misinterpreted the histories of myriad institutions and polities. Consider, for example, Edgardo Campos and his colleagues at the World Bank. While they trace the East Asian “miracle” to “home grown approaches” [Campos et al. Reference Campos2013: 2], and invoke books by Chalmers Johnson, Alice Amsden, Stephan Haggard, and Robert Wade by way of support, they ignore the fact that all four authors give foreign models prominent positions in their interpretations of Asian success. “Japan looked to the United States and Europe,” explains Wade. “Taiwan and Korea look more to Japan, with the perception that they are descending the same stretch of the river (in the Japanese metaphor) as Japan did fifteen to twenty-five years ago” [Wade Reference Wade1990: 334].Footnote 16

The relevant question, therefore, is not whether developing countries should import and adapt foreign models but which models are most likely to bear fruit under what conditions. The answer to that question offers insight into the systematic amnesia that is overtaking the development policy community today, for many—if by no means all—of the most successful models are found in decidedly unattractive polities including not only Nazi Germany but fascist Japan as well. In fact, Johnson notes that his book on Japanese industrial policy, MITI and the Japanese Miracle, has frequently been portrayed as a thinly veiled “defense of fascism” [Johnson Reference Johnson and Woo-Cumings1999: 51], and Atul Kohli reminds us that the Estado Novo declared by Vargas eventually “came to resemble its fascist counterparts in Europe” [Kohli Reference Kohli2004 388-389], in part due to the influence of “German and Italian immigrants.”

But the problem is not limited to imports with unsavory roots. While institutions that originated in Nazi Germany are for obvious reasons particularly tainted [Reinman Reference Reinman2000: 233; Auer Reference Auer2001: 14], they arguably differ in degree—rather than kind—from institutions more generally. Policymakers have also been known to repackage policies and programs that have foreign but democratic origins, for example, in order to take political credit or deflect nationalist hostility [Linden 2009: 105] and the originality of their efforts cannot be taken for granted either. In fact, the very notion of an “original” or “authentic” institution may well be an academic construct; in a world of trade, travel, war, and immigration, institutions are in constant motion and dialogue, their level of “authenticity” is a matter of degree (and perhaps type) rather than kind, and the comparative historical sociologist’s job is in part to unearth their histories.Footnote 17

What are the broader implications of my analysis? I will briefly discuss three important lessons. First, the search for homegrown or southern grown development policies is at best futile and at worst misguided. Institutions are among the few northern products that developing countries can—at least theoretically—import for free [Romer Reference Romer1993]. Sometimes they transfer seamlessly. Other times they demand adaptation. And often they refuse transfer outright. But the idea that developing country policymakers can readily differentiate foreign and domestic institutions, and should systematically turn their backs on the latter, is preposterous. The real questions are “which,” “when,” and “how,” not “whether.”Footnote 18

Second, the broader literature on “models of capitalism” [Crouch Reference Crouch2005] is equally vulnerable. After all, the model builders in question [Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001; Lalenis et al. Reference Lalenis2003; LaPorta et al. Reference LaPorta2008; Schneider Reference Schneider2013] have at times implied that institutions are “hermetically sealed” and “fixed” [Crouch Reference Crouch2005: 451]. However, the evidence I have adduced implies cross-fertilization and learning, and thus counsels for interpretations that take “translation, hybridization, and recombination” [Schneiberg and Clemens Reference Schneiberg and Clemens2006: 218] into account—including both Thelen’s sense that the original German model has survived neither by inertia nor inflexibility but by “ongoing, active adaptation to new problems” [Thelen Reference Thelen2007: 248] and revisionist accounts that come from within the “comparative capitalism” literature more generally [see, e.g., Jackson and Deeg Reference Jackson and Deeg2008: 554].Footnote 19

And, finally, the literature on “translation, hybridization, and recombination”—which is to say the literature on social change—needs to recognize that causality need not flow “from big to small” but can sometimes flow “from small to large, from the arbitrary to the general, from the minor event to the major development” [Abbott Reference Abbott1988: 173; see also Przeworski Reference Przeworski2004: 184]. While the Germans have typically been portrayed as minor players in Latin American history, they established institutions that have come to play a “major role” [Cuervo and Steenwyk Reference Costa1986: 5; Castro Reference Castro1999: 47] in the region’s economies—and could go on to play an even more “major role” [Sturgeon et al. Reference Sturgeon2013: 67] if they continue to evolve as planned. We would therefore do well to recognize that “small numbers” can translate into “great impact” [Buchenau Reference Buchenau2001]—not only in Latin America but beyond.