Public bathroom access for transgender people, or those whose internal gender identity does not match their birth sex,Footnote 1 is a controversial issue in the United States. Almost half the states have introduced some form of legislation that restricts bathroom access to the sex on one’s birth certificate (The New York Times, 2017). Most notably, North Carolina successfully passed the wide-sweeping Public Facilities Privacy and Security Act (SL 2016-3) in 2016. This legislation had ripple effects on U.S. politics and the economy, with several sports leagues and businesses withdrawing their activities from North Carolina by way of protest (Berman, Reference Berman2017). Ultimately, federal courts stepped in to restrict the state’s power to inhibit freedom of bathroom choice for transgender people (Levin, Reference Levin2019). Other jurisdictions have taken the opposite route, passing laws that protect transgender bathroom access rights. For example, New York State recently passed the Gender Expression Non-Discrimination Act (Senate Bill S1047), a wide-reaching bill that affirms transgender bathroom access rights as well as other civil rights for transgender people (Stewart-Cousins, Reference Stewart-Cousins2019).

Mirroring the varied legislative activity across the United States, about half of the American public supports the restriction of bathroom access, while the other half supports freedom of bathroom access (McCarthy, Reference McCarthy2017). Because legislation tends to follow public opinion, at least to some extent (Lax & Phillips, Reference Lax and Phillips2009; Soroka & Wlezien, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010), it is important to understand what motivates people to support or oppose bathroom restrictions. Beyond informing political and moral psychology, this knowledge may also be of great value to applied researchers and activists whose interventions depend on an accurate understanding of how people form their opinions. In the current article, we focus on the role of disgust and disgust-driven moral concerns in attitudes toward bathroom restrictions.

Role of disgust in support for bathroom restrictions

The emotion of disgust features prominently in real-world debates around bathroom restrictions. For example, one radio advertisement described the possibility of “men in women’s bathrooms” as “filthy” and “disgusting” (Wright, Reference Wright2015). It thus seems plausible that disgust factors into support for restrictive bathroom policies. While Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Flores, Haider-Markel, Lewis, Tadlock and Taylor2017) found a positive relationship between disgust and support for bathroom restrictions, no other published research has investigated disgust as a contributor to attitudes toward bathroom restrictions. Therefore, the first goal of our research was to clarify whether disgust predicts support for bathroom restrictions. In particular, we examined whether individual differences in disgust,Footnote 2 or the general tendency to experience disgust, are associated with support for bathroom restrictions.

Basic research indicates that there are a number of distinct subtypes of disgust (Haidt et al., Reference Haidt, McCauley and Rozin1994; Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Williams, Tolin, Abramowitz, Sawchuk, Lohr and Elwood2007; Tybur et al., Reference Tybur, Lieberman, Kurzban and DeScioli2012). Of these, three subtypes may be most likely to predict support for bathroom restrictions: pathogen disgust, sexual disgust, and injury disgust. Pathogen disgust is associated with potential sources of disease (e.g., feces, insects such as roaches and maggots), and it is believed to have evolved as a disease-avoidance mechanism. Pathogen disgust may be connected to support for bathroom restrictions as some Americans associate transgender people with HIV/AIDS (Waters, Reference Waters2017). Because pathogen disgust promotes avoidance of real or imagined disease threats (Schaller & Park, Reference Schaller and Park2011), those higher in pathogen disgust might be motivated to avoid contact with transgender people, leading to increased support for bathroom restrictions. Additionally, the disease-avoidance system can be triggered by any deviation from a given culture’s norms of appearance, regardless of whether such deviation is actually caused by disease (Kurzban & Leary, Reference Kurzban and Leary2001). This tendency is believed to be rooted in psychological adaptations that infer pathogens from unusual appearances. Because not all appearances considered unusual within a culture actually entail pathogens, this adaptation often results in false positives, in turn contributing to stigmatization of some groups (Kurzban & Leary, Reference Kurzban and Leary2001). Transgender people may deviate from mainstream social norms about how men and women should look, insofar as they choose to present themselves in accordance with their gender identity rather than their birth sex. Thus, transgender people’s gender presentation may trigger pathogen disgust in some people, who may support bathroom restrictions as a way of distancing themselves from the source of that disgust. This line of reasoning suggests that higher pathogen disgust should be associated with increased support for bathroom restrictions.

Sexual disgust may also be linked to support for bathroom restrictions. Sexual disgust is triggered by behaviors that are perceived to jeopardize long-term reproductive success (i.e., successfully producing offspring and maximizing their chance of survival; Tybur et al., Reference Tybur, Lieberman and Griskevicius2009). Americans’ lay understanding of what it means to be transgender tends to be linked to gender confirmation surgery, which modifies the sexual organs (Tadlock, Reference Tadlock, Taylor and Haider-Markel2015). The prospect of removing or modifying the sexual organs may cause some people to perceive transgender identity as jeopardizing reproductive success, causing sexual disgust. Those who are higher in sexual disgust may therefore support bathroom restrictions as a way to avoid contact with the people who trigger that disgust.

A third form of disgust that may be related to support for bathroom restrictions is injury disgust. Injury disgust is triggered by violations of the outer body envelope (e.g., injuries, blood, amputations, etc.; Rozin et al., Reference Rozin, Haidt, McCauley, Lewis and Haviland-Jones2000). While some have argued that injury disgust is a subtype of pathogen disgust (Curtis & Biran, Reference Curtis and Biran2001), Kupfer (Reference Kupfer2018) proposed that injury disgust is a separate construct. Specifically, Kupfer argued that injury disgust is akin to a negative form of empathy. By this account, people feel vicarious pain when they see or think about someone else’s injury. This feeling sometimes gets labeled as disgust in cases when a person cannot think of a better word to describe the feeling. As mentioned, many Americans associate transgender identity with gender confirmation surgery (Tadlock, Reference Tadlock, Taylor and Haider-Markel2015). For some, the very idea of such body modifications may trigger injury disgust. Bathroom restrictions may thus be seen as a means of avoiding the discomfort of injury disgust, leading those high in injury disgust to support restrictive policies.

Role of moral values in support for bathroom restrictions

Another way that disgust may influence support for bathroom restrictions is through its influence on moral values. According to Moral Foundations Theory, an influential model of human morality, moral concerns about purity are closely tied to pathogen disgust (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and Ditto2013), with several studies supporting a link between disgust and purity (Eskine et al., 2011; Landmann & Hess, Reference Landmann and Hess2018; Seidel & Prinz, Reference Seidel and Prinz2013; Wagemans, Brandt, & Zeelenberg, Reference Wagemans, Brandt and Zeelenberg2018; Wagemans Brandt, & Zeelenberg, Reference Wagemans, Brandt and Zeelenberg2018; but see also Landy & Goodwin, Reference Landy and Goodwin2015). Purity concerns pertain to sacralized attitudes around virtuous use of the body, living in accordance with God’s plan, upholding the natural, and maintaining the sanctity of the soul (Haidt & Graham, 2008). Purity concerns are believed to represent an evolutionary offshoot of the disease-avoidance system, insofar as they reflect the moralization of behaviors that could physically or spiritually contaminate the self or others.

Concerns about purity are prominent in public and political discourse around bathroom restrictions. For example, during an interview with Rolling Stone magazine, conservative activists described transgender people as “perverted” and expressed worry that open bathroom policies would “[make] our city … godless” (Posner, Reference Posner2018). If taken at face value, support for bathroom restrictions may be driven by the desire to limit purity transgressions; thus, those who endorse purity values more strongly should show higher support for restrictive policies. Consistent with this idea, some previous research suggests that purity concerns play an important role in attitudes toward certain body-centric political issues, such as abortion, euthanasia, and same-sex marriage (Inbar, Pizarro, & Bloom, Reference Inbar, Pizarro and Bloom2009; Inbar, Pizarro, Knobe, & Bloom, Reference Inbar, Pizarro and Bloom2009; Koleva et al., Reference Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto and Haidt2012; Tilburt et al., Reference Tilburt, James, Jenkins, Antiel, Curlin and Rasinski2013). If pathogen disgust does indeed drive purity values (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and Ditto2013), and purity values drive support for bathroom restrictions, then purity values should mediate the relationship between pathogen disgust and support for bathroom restrictions. This causal model, shown in Figure 1, offers a more theoretically complete model than has been tested in previous research.

Figure 1. Causal mediation model where pathogen disgust causes concerns about purity, which in turn cause support for policies that limit impurity (i.e., bathroom restrictions). Path a represents the causal effect of disgust on purity; path b represents the causal effect of purity on support for bathroom restrictions. Path c is the indirect effect, or the effect of disgust on support for bathroom restrictions through purity. Lastly, path (c’) is the direct effect of disgust on support for bathroom restrictions, or the remaining effect after the indirect effect is accounted for.

In addition to assessing whether purity concerns are related to support for bathroom restrictions, we evaluated the relative importance of purity concerns compared with other moral values. Research in the tradition of Moral Foundations Theory suggests that purity concerns play a central role in at least some policy positions (Inbar, Pizarro, & Bloom, Reference Inbar, Pizarro and Bloom2009; Inbar, Pizarro, Knobe, & Bloom, Reference Inbar, Pizarro and Bloom2009; Koleva et al., Reference Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto and Haidt2012; Tilburt et al., Reference Tilburt, James, Jenkins, Antiel, Curlin and Rasinski2013). By contrast, according to the Theory of Dyadic Morality, moral concerns about harm and welfare are the strongest moral concerns relevant to policy positions (Schein & Gray, Reference Schein and Gray2017). Indeed, this theory goes so far as to argue that any effects of purity or disgust on policy positions can be fully accounted for by harm concerns (Schein & Gray, Reference Schein and Gray2015; Schein et al., Reference Schein, Ritter and Gray2016).

With respect to bathroom restrictions, concerns about protecting the welfare of various groups arise frequently in the national debate. Proponents of bathroom restrictions often argue that bathroom access rights would create a threat to cisgender people (i.e., people whose sex at birth aligns with their gender identity), especially women and girls (Fernandez & Blinder, Reference Fernandez and Blinder2015). Conversely, those who are opposed to bathroom restrictions argue that transgender people may be harmed if they are forced to use bathrooms that do not align with their gender identity or presentation. Indeed, one survey found that 68% of transgender people reported having experienced verbal harassment in gender-segregated public restrooms, and 9% reported physical assault (Herman, Reference Herman2013). Given the salience of both purity and harm in public debate about bathroom restrictions, we investigated the relative importance of purity and harm concerns in predicting support for bathroom restrictions. We also tested the prediction from the Theory of Dyadic Morality that the effect of disgust on support for restrictive policies would be fully accounted for by harm concerns (Schein & Gray, Reference Schein and Gray2015; Schein et al., Reference Schein, Ritter and Gray2016).

We examined the influence of both general purity and harm concerns and bathroom-related purity and harm concerns. General moral concerns are not tied to any particular issue but instead reflect a general tendency to endorse particular values. By contrast, bathroom-related concerns (henceforth, bathroom concerns) are subjective concerns about harm or impurity that could result from transgender people accessing the bathroom that aligns with their gender identity rather than their sex assigned at birth.

Different influences for different transgender identities?

Finally, we investigated whether support for bathroom restrictions, and the predictors of that support, might differ when people consider trans women using women’s bathrooms versus trans men using men’s bathrooms. Trans women are individuals who were assigned male at birth but who identify as women; trans men are those who were assigned female but who identify as men. Anecdotally, discourse around bathroom restrictions seems focused on “men in women’s bathrooms” (e.g., Posner, Reference Posner2018). This could be taken as a concern about anyone with male genitalia entering women’s bathrooms, including some trans women. If this is correct, then we would expect that bathroom bill support varies depending on which target identity is being made salient. Specifically, we predicted higher support for bathroom restrictions when people consider trans women using women’s bathrooms compared with trans men using men’s bathrooms. We also expected higher concerns about possible harm toward cisgender people when the trans woman target identity is salient. Finally, we investigated the possibility of interactive effects on support for restrictive policies, such as interactions between disgust and target identity, and moral concerns and target identity.

Methods

Design

We conducted an online, observational, population-based study with a focus on Americans. We used quota sampling to recruit an approximately nationally representative sample in terms of gender, race, ethnicity, and geographic diversity. All aspects of the study were cross-sectional, with the exception that participants were randomly assigned to answer the questions either with respect to trans women or with respect to trans men. Methods and analyses were preregistered on OSF.io (https://osf.io/5xnsa/). During the review process some changes from the preregistered analyses were made; we note deviations from the preregistration throughout.

Participants

Adult participants (N = 663) were recruited using the Qualtrics.com platform and compensated with digital currencies (e.g., points, e-rewards) approximately equivalent to US $1. The starting sample size was determined by our research budget. An a priori power analysis using the largest of our preregistered regression models suggested that this sample would provide approximately 90% power to detect a small-medium effect (r = .2). Participants all had U.S. IP addresses and were recruited so as to obtain representation from the Northeast, Midwest, South, and West of the country. Participants who completed the survey were excluded if their completion time was more than 1 median absolute deviation below the median time (Mdnminutes = 10.35, MADminutes = 3.51, cutoff time = 6.84 minutes, n excluded = 86). Finally, a few individuals indicated that they were under 18 years of age and therefore were also excluded from analysis (n = 2). The final sample (N = 575) had a mean age of 45.04 years (SD = 16.55). The sample was 15.1% Hispanic, 70.5% White, 13.9% Black or African American, and 11.8% Asian. Lastly, 49.4% identified as female, 48.0% identified as male, 2.4% were transgender, with fewer than 1% identifying as none of male, female, or transgender. See Section A of the supplemental materials for a more detailed breakdown of our quota-defined demographic groups and how we measured birth sex and (trans)gender identity.

Materials and measures

Target identity

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two versions of the survey: a version asking about bathroom restrictions as they pertain specifically to trans women using a women’s bathroom or a version pertaining to trans men using a men’s bathroom. The questions on each version were identical for the two cohorts except for the gender specified. In what follows, the target identity is indicated in brackets, with the trans female version shown first. Before answering any questions about bathroom restrictions, participants read the following introduction guided by best practices for describing transgender identity (GenIUSS Group, Reference Herman2014): “For this survey, we define a transgender person as someone who experiences a different gender identity from their sex at birth. For example, a person who was born into a [male/female] body but feels that they are a [woman/man] or lives as a [woman/man] would be transgender. Some transgender people change their physical appearance so that it matches their internal gender identity. Some transgender people take hormones and some have surgery. A transgender person may be of any sexual orientation—straight, gay, lesbian or bisexual.”

Support for bathroom restrictions

To measure support for restrictive bathroom policies, participants were asked to indicate how much they endorsed this statement: “When it comes to public bathrooms, someone who was born into a [male/female] body should be required to use the [men’s/women’s] bathroom, even if they feel that they are a [woman/man]” (1–6, strongly disagree to strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater support for bathroom restrictions.

Moral wrongness

For exploratory purposes, participants were also asked about their moral position on the issue: “Regardless of any policies, how morally wrong would be for someone who was born into a [male/female] body to use the [women’s/men’s] bathroom, if they feel they are a [woman/man]?” (1–6, never morally wrong to always morally wrong). Because the moral wrongness item yielded similar results as the policy support measure, full results from analyses with this item are included in Section B of the supplemental materials.

Trait disgust

Pathogen and sexual disgust were measured with the relevant scales from the Three Domain Disgust Scale (TDDS; Tybur et al., Reference Tybur, Lieberman and Griskevicius2009). Each subscale asks participants to rate how disgusting they find seven disgusting stimuli (e.g., “Stepping on dog poop,” 0–6, not at all disgusting to extremely disgusting;

![]() $ \alpha =.81 $

for pathogen subscale,

$ \alpha =.81 $

for pathogen subscale,

![]() $ \alpha =.86 $

for sexual disgust subscale). The TDDS also contains a subscale that measures moral disgust, operationalized as disgust toward dishonesty and theft. We did not expect that this scale would be related to support for restrictive policies, and indeed it was not. Results for this scale can be found in Section C of the supplemental materials. To measure injury disgust, we used a modified version of the injury disgust scale developed by Kupfer (Reference Kupfer2018). We modified the original scale to improve its psychometric properties; see Section D of the supplemental materials for details. As with the TDDS subscales, the injury scale asks participants to rate how disgusting they find three stimuli (e.g., “Seeing a person impaled through the neck by a branch,” 0–6, not at all disgusting to extremely disgusting,

$ \alpha =.86 $

for sexual disgust subscale). The TDDS also contains a subscale that measures moral disgust, operationalized as disgust toward dishonesty and theft. We did not expect that this scale would be related to support for restrictive policies, and indeed it was not. Results for this scale can be found in Section C of the supplemental materials. To measure injury disgust, we used a modified version of the injury disgust scale developed by Kupfer (Reference Kupfer2018). We modified the original scale to improve its psychometric properties; see Section D of the supplemental materials for details. As with the TDDS subscales, the injury scale asks participants to rate how disgusting they find three stimuli (e.g., “Seeing a person impaled through the neck by a branch,” 0–6, not at all disgusting to extremely disgusting,

![]() $ \alpha =.84 $

).

$ \alpha =.84 $

).

General moral concerns

We used the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and Ditto2011) to measure general moral concerns relating to harm and purity. This questionnaire asks participants how relevant different considerations are for their moral judgments, and how much they agree or disagree with statements that tap different moral concerns. To measure general concerns related to harm, participants completed the harm subscale (e.g., “whether or not someone suffered emotionally,” 1–6, not at all relevant to extremely relevant; “Compassion for those who are suffering is the most crucial virtue”; 1–6, strongly disagree to strongly agree;

![]() $ \alpha =.71 $

). To measure general moral concerns related to purity, participants completed the purity subscale (e.g., “whether or not someone did something disgusting,” 1–6, not at all relevant to extremely relevant; “I would consider some things wrong on the grounds that they are unnatural”; 1–6, strongly disagree to strongly agree,

$ \alpha =.71 $

). To measure general moral concerns related to purity, participants completed the purity subscale (e.g., “whether or not someone did something disgusting,” 1–6, not at all relevant to extremely relevant; “I would consider some things wrong on the grounds that they are unnatural”; 1–6, strongly disagree to strongly agree,

![]() $ \alpha =.83 $

).

$ \alpha =.83 $

).

For exploratory purposes, participants also completed the other Moral Foundations Questionnaire subscales; results for these scales can be found in Section E of the supplemental materials. Also, while we preregistered that we would take sum scores of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire subscales, the standard scoring of the instrument is to take the arithmetic mean (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and Ditto2011).

Bathroom harm and purity concerns

Bathroom purity concerns

To measure purity as it relates specifically to bathroom restrictions, we asked participants to imagine that “someone who was born into a [male/female] body, but feels that they are a [woman/man], uses the [women’s/men’s] bathroom.” Participants were then asked how much they agreed “that would be obscene,” “that would be impure,” “there is nothing sinful about that,” and “there is nothing perverted about that” (latter two items reverse-scored: 1–6, strongly disagree to strongly agree,

![]() $ \alpha $

= .85). These descriptors were taken from the Moral Foundations Dictionary (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009). A purity index was computed by taking the arithmetic mean, with higher scores indicating greater concern about purity.

$ \alpha $

= .85). These descriptors were taken from the Moral Foundations Dictionary (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009). A purity index was computed by taking the arithmetic mean, with higher scores indicating greater concern about purity.

Bathroom harm concerns

In the context of bathroom restrictions, people might be concerned about harm to cisgender people if bathroom choice is left unrestricted. For example, people may be concerned that if trans women are allowed into women’s bathrooms, cisgender women and girls may be harmed. To measure this type of concern, participants were asked to “Imagine a policy that would allow someone who was born into a [male/female] body to use the [women’s/men’s] bathroom, so long as that person feels that they are a [woman/man].” They were then asked to indicate whether the policy would “make bathrooms more dangerous for [women and girls/men and boys] who are not transgender,” “might harm [women and girls/men and boys] who are not transgender,” or is “perfectly safe for [women and girls/men and boys] who are not transgender” (final item reverse-scored; 1–6, strongly disagree to strongly agree,

![]() $ \alpha =.85 $

). A cisgender harm index was computed by taking the arithmetic mean. Higher scores indicate greater concern for harm toward cisgender people.

$ \alpha =.85 $

). A cisgender harm index was computed by taking the arithmetic mean. Higher scores indicate greater concern for harm toward cisgender people.

People may also be concerned that bathroom restrictions could harm transgender people. For example, people may be concerned that if a trans woman was required to use the men’s bathroom, she may be harmed. To measure this concern, we asked participants to imagine “a policy that would require someone who was born into a [male/female] body to use the [men’s/women’s] bathroom, even if that person feels that they are a [woman/man].” They were then asked to indicate whether the policy would “make bathrooms more dangerous for this person,” “might harm this person,” or is “perfectly safe for this person” (final item reverse-scored; 1–6, strongly agree to strongly disagree,

![]() $ \alpha =.83 $

). A transgender harm index was computed by taking the arithmetic mean. Higher scores indicate greater concern for harm toward transgender people.

$ \alpha =.83 $

). A transgender harm index was computed by taking the arithmetic mean. Higher scores indicate greater concern for harm toward transgender people.

In the preregistration of the study, we planned to combine the measures of cisgender and transgender harm into a single bipolar scale of perceived victim. We ultimately decided to retain cisgender and transgender harm as separate measures, for two reasons. First, we decided that it was more theoretically coherent to treat these as separate constructs, given the feasibility that a person could be concerned about harm to both cisgender and transgender people. Second, the scales were not strongly correlated (r = –.29), suggesting that they may be at least partially distinct constructs.

Theoretically motivated control measures

Disgust is largely a negative emotion. To isolate the effects of disgust from trait negative affectivity, or the tendency to feel any sort of negative emotion, participants completed the neuroticism subscale of the Big Five Inventory-2-Short Form (

![]() $ \alpha =.83 $

). To control for the possible confound of political orientation, participants provided ratings on social conservatism (“When it comes to social issues, do you consider yourself to be …”; 1–7, strongly conservative to strongly liberal) and economic conservatism (“When it comes to economic issues, do you consider yourself to be …”: 1–7, strongly conservative to strongly liberal). We reverse-scored these items so that higher scores on each would indicate greater conservatism. Because these two items were highly correlated (r = .85), we averaged them to form a composite measure of political conservatism.

$ \alpha =.83 $

). To control for the possible confound of political orientation, participants provided ratings on social conservatism (“When it comes to social issues, do you consider yourself to be …”; 1–7, strongly conservative to strongly liberal) and economic conservatism (“When it comes to economic issues, do you consider yourself to be …”: 1–7, strongly conservative to strongly liberal). We reverse-scored these items so that higher scores on each would indicate greater conservatism. Because these two items were highly correlated (r = .85), we averaged them to form a composite measure of political conservatism.

Demographics

Participants were asked their age, race, ethnicity, religious attendance (every week, almost every week, once or twice a month, a few times a year, never), education, and LGB identification (yes or no). At the end of the survey, participants were asked “how do you describe yourself?,” with response options of “male,” “female,” “transgender,” or “do not identify as male, female, or transgender.” Because so few participants responded with the last two options, we only included those who identified as male or female in the final analyses. In the preregistration of the study, we planned to include these demographic variables as covariates in all regression analyses. However, for ease of interpretation, we report simplified models that omit the full set of demographic covariates. Analyses including all covariates can be found in the supplementary materials (Section F).

Procedure

After giving informed consent, participants were asked to commit to providing their “best and honest answers” during the survey; no data were collected from individuals who did not make this commitment. Participants then indicated their age, sex assigned at birth, race and ethnicity, and the state they lived in. Next, participants saw two blocks in random order. One block contained the disgust measures (pathogen, sexual, and moral disgust scales from the TDDS and the injury disgust scale) and general moral concern measures (Moral Foundations Questionnaire). The other block contained bathroom harm and purity items, along with the policy support and moral wrongness items. Within each block, measures were presented in random order, and within each measure, items were in random order. For the bathroom concern items, participants were randomly assigned to one of the two target identities; that is, they answered the bathroom harm and purity questions with respect to either trans women or trans men. Finally, participants indicated their gender, social and economic conservatism, education, religious attendance, and LGB identification.

Results

Disgust and support for bathroom restrictions

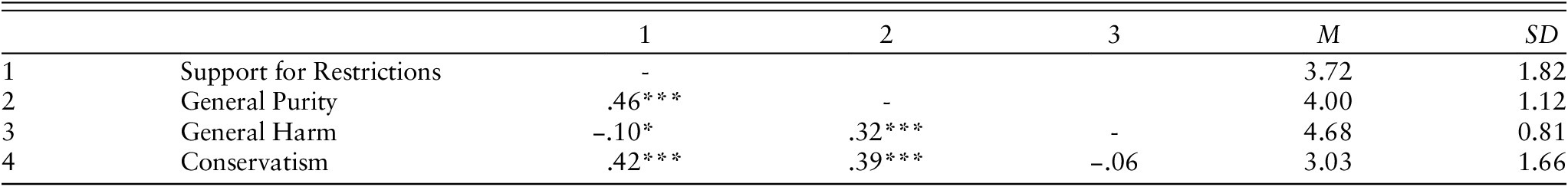

We first examined means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations among support for restrictive bathroom policies, disgust subtypes, neuroticism, and conservatism (Table 1). Conservatism showed the strongest relationship to bathroom bill support, such that the more conservative people were, the more they tended to support bathroom restrictions. The next-strongest associations were the pathogen and sexual disgust subtypes, which indicated that the greater one’s tendency to feel pathogen or sexual disgust, the greater one’s tendency to support bathroom restrictions. Injury disgust and neuroticism showed small to negligible associations with support for bathroom restrictions.

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Disgust Subtypes and Support for Bathroom Restrictions

Note. M = mean (sum score for neuroticism). SD = standard deviation.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05 (two-tailed).

To test the independent effects of disgust subtypes on support for bathroom restrictions, we ran a regression with support for bathroom restrictions as the outcome and pathogen disgust, sexual disgust, injury disgust, neuroticism, and conservatism as predictors,

![]() $ {R}_{adj}^2=.22 $

,

$ {R}_{adj}^2=.22 $

,

![]() $ F\left(5,567\right)=33.1 $

,

$ F\left(5,567\right)=33.1 $

,

![]() $ p<.001 $

(two-tailed). Table 2 shows that conservatism was the strongest predictor of support for bathroom restrictions in this model; however, pathogen disgust emerged as the most important disgust subtype, accounting for more than four times as much unique variance in policy support as sexual disgust. Importantly, sexual and injury disgust were no longer statistically significant despite the high power of the study. The pattern of results was largely the same when including several demographic covariates; see Section F of the supplemental materials for models that include demographics variables.

$ p<.001 $

(two-tailed). Table 2 shows that conservatism was the strongest predictor of support for bathroom restrictions in this model; however, pathogen disgust emerged as the most important disgust subtype, accounting for more than four times as much unique variance in policy support as sexual disgust. Importantly, sexual and injury disgust were no longer statistically significant despite the high power of the study. The pattern of results was largely the same when including several demographic covariates; see Section F of the supplemental materials for models that include demographics variables.

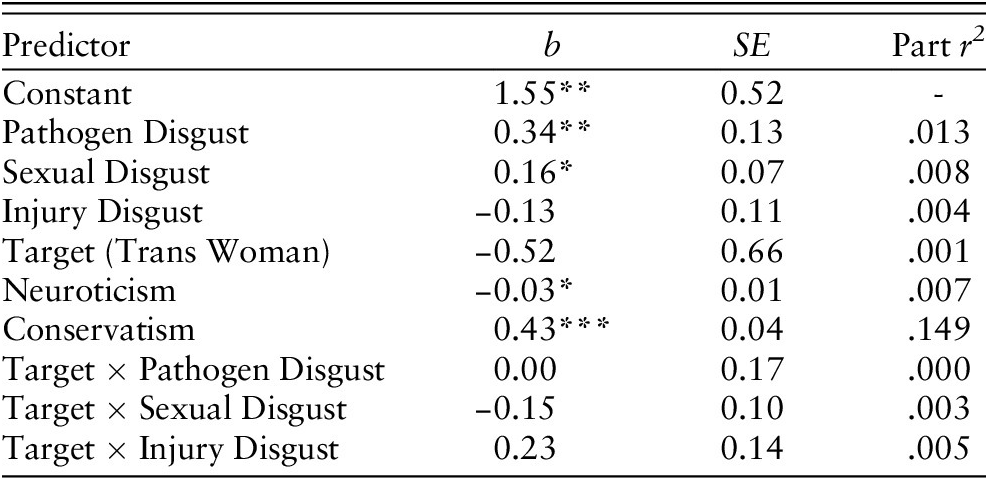

Table 2. Support for Bathroom Restrictions Predicted by Disgust Subtypes, Neuroticism, and Conservatism.

Note. Nobs = 573. SE = Standard Error (robust).

Part r 2 = squared semipartial correlation.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05 (two-tailed).

General moral concerns and support for bathroom restrictions

Table 3 shows means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations among support for bathroom restrictions, general purity concerns, general harm concerns, and conservatism. Purity concerns had the strongest association with support for bathroom restrictions, such that the greater one’s general tendency to be concerned with violations of purity, the greater the tendency to support bathroom restrictions. This relationship was slightly stronger than conservatism and much stronger than harm.

Table 3. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among General Moral Concerns and Support for Bathroom Restrictions

Note. M = mean. SD = standard deviation.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05 (two-tailed)

To isolate the unique effects of each variable on support for restrictive bathroom policies, we conducted a regression with purity concerns, general harm concerns, and conservatism predicting policy support,

![]() $ {R}_{adj}^2=.31 $

,

$ {R}_{adj}^2=.31 $

,

![]() $ F(3,569)=88.2 $

,

$ F(3,569)=88.2 $

,

![]() $ p<.001 $

(two-tailed). As seen in Table 4, purity emerged as the strongest predictor of policy support, independent of and indeed far above harm and conservatism. With that said, harm was a reliable negative predictor of bathroom bill support, such that the greater the general tendency to be concerned about harm and welfare, the less support for bathroom restrictions. Results did not differ after adding several demographic covariates to the model; see Section F of the supplemental materials.

$ p<.001 $

(two-tailed). As seen in Table 4, purity emerged as the strongest predictor of policy support, independent of and indeed far above harm and conservatism. With that said, harm was a reliable negative predictor of bathroom bill support, such that the greater the general tendency to be concerned about harm and welfare, the less support for bathroom restrictions. Results did not differ after adding several demographic covariates to the model; see Section F of the supplemental materials.

Table 4. Support for Bathroom Restrictions Predicted By General Moral Concerns and Conservatism

Note. Nobs = 573. SE = Standard Error (robust).

Part r 2 = squared semipartial correlation.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05 (two-tailed).

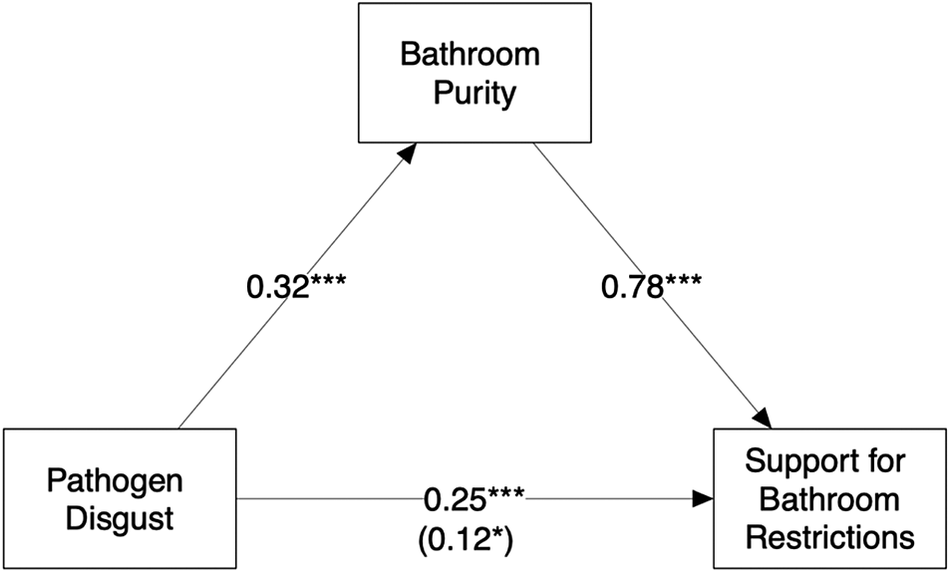

Next, we tested the Moral Foundations Theory hypothesis that pathogen disgust causes moral concerns about purity, which then causes people to favor morally charged policies that limit the potential for purity violations (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and Ditto2013; Koleva et al., Reference Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto and Haidt2012). Figure 2 shows the results of a PROCESS mediation analysis (Hayes, Reference Hayes2018) with bootstrapped standard errors (simple bias-corrected and accelerated with 10,000 replicates). We found that purity partially mediated the relationship between disgust and support for bathroom restrictions. The indirect effect of pathogen disgust through general purity concerns (b = 0.21, SE = 0.04, p < .001) accounted for 55% of the total effect (b = 0.38, SE = 0.07, p < .001), a fairly large effect size.

Figure 2. Pathogen disgust and support for bathroom restrictions mediated by general purity.

*** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05 (two-tailed)

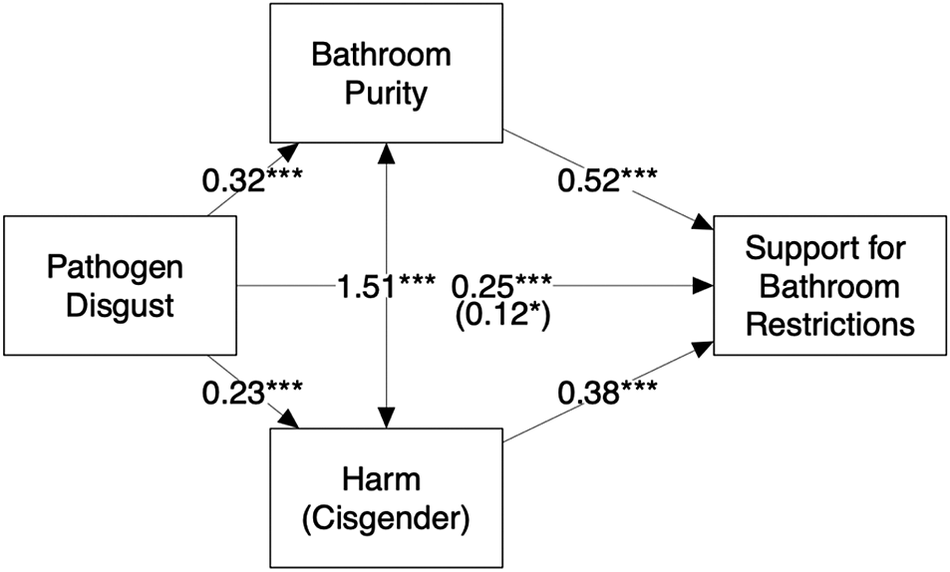

As described earlier, the Theory of Dyadic Morality argues that harm is the central moral concern (Gray & Wegner, Reference Gray, Wegner, Mikulincer and Shaver2012). Beyond merely arguing that harm is more important than purity, proponents of this theory have claimed that harm concerns can fully account for the effect of disgust on moral judgments (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Schein and Ward2014; Schein et al., Reference Schein, Ritter and Gray2016). Our data afforded an opportunity to test this claim. Specifically, we added general harm concerns as a parallel mediator to the previous mediation model (Figure 3). A PROCESS mediation analysis (Hayes, Reference Hayes2018) with bootstrapped standard errors (bias-corrected and accelerated with 10,000 bootstrap replicates) showed that the indirect effect via general purity concerns (b = 0.25, SE = 0.04, p < .001) remained significant when including general harm concerns in the model. Indeed, the indirect path via purity concerns was over three times as large as the indirect effect via harm concerns (b = –0.08, SE = 0.02, p < .001). This argues against the Theory of Dyadic Morality (Schein et al., Reference Schein, Ritter and Gray2016), insofar as the effect of pathogen disgust on support for bathroom restrictions was not explained away by general harm concerns (Graham, Reference Graham2015).

Figure 3. Pathogen disgust and support for bathroom restrictions mediated by general purity and general harm.

*** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05 (two-tailed)

Bathroom moral concerns

For bathroom moral concerns, or concerns about behaviors that relate specifically to bathroom restrictions, zero-order correlations (Table 5) indicated strong, positive relationships between support for bathroom restrictions and purity concerns, and between support for bathroom restrictions and cisgender harm concerns, and and a moderate relationship between transgender harm concerns and support for bathroom restrictions.

Table 5. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Bathroom Moral Concerns, and Support for Bathroom Restrictions

Note. M = mean. SD = standard deviation.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05 (two-tailed)

Using regression, we then examined the unique contribution of purity concerns, cisgender harm concerns, transgender harm concerns, and conservatism to support for bathroom restrictions,

![]() $ {R}_{adj}^2=.53 $

,

$ {R}_{adj}^2=.53 $

,

![]() $ F(4,569)=164.7 $

,

$ F(4,569)=164.7 $

,

![]() $ p<.001 $

(two-tailed). As Table 6 shows, purity was the strongest predictor of bathroom bill support.

$ p<.001 $

(two-tailed). As Table 6 shows, purity was the strongest predictor of bathroom bill support.

Table 6. Support for Bathroom Restrictions Predicted By Bathroom Moral Concerns, and Conservatism

Note. Nobs = 574. SE = Standard Error (robust).

Part r 2 = squared semipartial correlation.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05 (two-tailed).

Next, we tested the Moral Foundations Theory hypothesis that pathogen disgust causes concerns about purity (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and Ditto2013), which then causes people to favor morally charged policies that limit the potential for purity violations (Koleva et al., Reference Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto and Haidt2012). In other words, the general tendency to feel disgust causes concern about the (im)purity of bathroom choices, which, in turn, causes support for bathroom restrictions. Using a PROCESS mediation analysis (Hayes, Reference Hayes2018) with bootstrapped standard errors (bias-corrected and accelerated with 10,000 replicates; model shown in Figure 4), we found that the indirect effect of pathogen disgust on bathroom bill support through bathroom purity concerns (b = 0.25, SE = 0.05, p < .001) explained about 66% of the total effect (b = 0.38, SE = 0.07, p < .001).

Figure 4. Pathogen disgust and support for bathroom restrictions mediated by bathroom purity concerns.

*** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05 (two-tailed)

We also tested the claim from the Theory of Dyadic Morality that harm concerns can fully account for the effect of disgust on moral judgments (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Schein and Ward2014; Schein et al., Reference Schein, Ritter and Gray2016). To do so, we added harm as a parallel mediator to the previous analysis (Figure 5). We focused on cisgender harm, since transgender harm was not correlated with pathogen disgust (r = .01, p = .12). Consistent with the analysis of general moral concerns, the indirect effect via bathroom purity concerns (b = 0.17, SE = 0.03, p < .001) remained significant even after including cisgender harm concerns in the model. Indeed, the indirect path via bathroom purity was almost twice as large as the indirect path via harm (b = 0.09, SE = 0.03, p < .001). This again argues against the Theory of Dyadic Morality, in that the effect of pathogen disgust on support for bathroom restrictions was not explained away by cisgender harm concerns (Graham, Reference Graham2015; Gray & Keeney, Reference Gray and Keeney2015; Schein et al., Reference Schein, Ritter and Gray2016).

Figure 5. Pathogen disgust and support for bathroom restrictions mediated by bathroom purity and cisgender harm concerns.

*** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05 (two-tailed)

Target Identity

Finally, we examined the role of transgender target identity in support for bathroom restrictions. As seen in Table 7, and contrary to our hypothesis, there was no overall difference in support for bathroom restrictions between the two target identity groups. Regarding bathroom moral concerns, Table 7 shows that there were no statistically significant differences between target identity groups for bathroom concerns about purity or transgender harm. However, as predicted, those in the trans women group expressed greater concerns about harm toward cisgender people relative to the trans men group, with a small to moderate effect size.

Table 7. Means, Standard Deviations, Effect Sizes, and Welch’s Two-Sample T-tests For Target Identity Groups

Note: d = Cohen’s d using pooled standard deviation. df = degrees of freedom. t = t-statistic. p = p-value (two-tailed).

We next tested for interactive effects of target identity and disgust subtypes on support for bathroom restrictions. We conducted a regression with policy support predicted by disgust subtypes, neuroticism, conservatism, target identity, and all three disgust subtype x target identity interactions,

![]() $ {R}_{adj}^2=.22 $

,

$ {R}_{adj}^2=.22 $

,

![]() $ F(9,563)=19.3 $

,

$ F(9,563)=19.3 $

,

![]() $ p<.001 $

(two-tailed). Table 8 shows that none of the three interactions were statistically significant (note that the trans man target identity is the reference level). That is, the relationships between support for bathroom restrictions and pathogen, sexual, and injury disgust were not reliably different between the trans men and trans women target identity groups.

$ p<.001 $

(two-tailed). Table 8 shows that none of the three interactions were statistically significant (note that the trans man target identity is the reference level). That is, the relationships between support for bathroom restrictions and pathogen, sexual, and injury disgust were not reliably different between the trans men and trans women target identity groups.

Table 8. Support for Bathroom Restrictions Predicted by Disgust Subtypes, Target Identity, Disgust by Target Interactions, Neuroticism, and Conservatism

Note. Nobs = 572. SE = Standard Error (robust).

Part r 2 = squared semipartial correlation.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05 (two-tailed).

To test for interactive effects of target identity and general moral concerns on support for bathroom restrictions, we conducted a regression with policy support predicted by general purity concerns, general harm concerns, target identity, conservatism, target identity x general purity concerns, and target identity x general harm concerns,

![]() $ {R}_{adj}^2=.31 $

,

$ {R}_{adj}^2=.31 $

,

![]() $ F(6,566)=44.7 $

,

$ F(6,566)=44.7 $

,

![]() $ p<.001 $

(two-tailed). Table 9 shows there were no significant interactions between target identity and general purity concerns or general harm concerns.

$ p<.001 $

(two-tailed). Table 9 shows there were no significant interactions between target identity and general purity concerns or general harm concerns.

Table 9. Support for Bathroom Restrictions Predicted by General Moral Concerns, Target Identity, General Concern by Target Interactions, and Conservatism

Note. Nobs = 573. SE = Standard Error (robust).

Part r 2 = squared semipartial correlation.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05 (two-tailed).

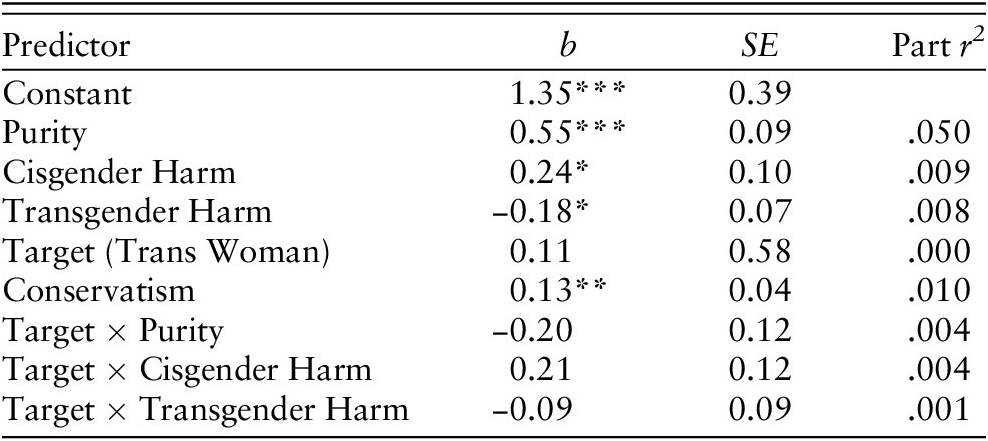

We next tested for interactive effects of target identity and bathroom moral concerns on support for bathroom restrictions. We conducted a regression with policy support predicted by bathroom purity, transgender harm, cisgender harm, target identity, conservatism, target identity x bathroom purity, target identity x transgender harm, and target identity x cisgender harm

![]() $ , {R}_{adj}^2=.54 $

,

$ , {R}_{adj}^2=.54 $

,

![]() $ F(8,565)=84.0 $

,

$ F(8,565)=84.0 $

,

![]() $ p<.001 $

(two-tailed). As shown in Table 10, there were no statistically significant interactions between target identity and purity, cisgender harm, or transgender harm.

$ p<.001 $

(two-tailed). As shown in Table 10, there were no statistically significant interactions between target identity and purity, cisgender harm, or transgender harm.

Table 10. Support for Bathroom Restrictions Predicted by Bathroom Moral Concerns, Target Identity, Bathroom Moral Concerns by Target Interactions, and Conservatism

Note. Nobs = 574. SE = Standard Error (robust).

Part r 2 = squared semipartial correlation.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05 (two-tailed).

Discussion

Trait disgust subtypes

This research sought to better understand the factors that influence attitudes toward policies that limit the choice of bathroom to an individual’s birth sex. We started by identifying three subtypes of disgust that could be related to bathroom bill support: pathogen disgust, sexual disgust, and injury disgust (Kupfer, Reference Kupfer2018; Tybur et al., Reference Tybur, Lieberman and Griskevicius2009). Although all three subtypes showed zero-order relationships with bathroom bill support, multivariable regression showed that pathogen disgust was the primary predictor of support for bathroom restrictions. Pathogen disgust may predict support for bathroom restrictions because some people associate transgender people with sexually transmitted diseases (Waters, Reference Waters2017) or because transgender people’s appearance triggers the disease-avoidance system in some people (as in Schaller & Park, Reference Schaller and Park2011). Either way, people who are high in pathogen disgust may support bathroom restrictions as a means to avoid contact with transgender people, thereby distancing themselves from a perceived disease threat. Importantly, the effect of pathogen disgust was independent from neuroticism, indicating that disgust effects are not due to negative affectivity. The effect of pathogen disgust was also independent from conservatism, an important result given that pathogen disgust and conservatism are correlated (Terrizzi et al., Reference Terrizzi, Shook and McDaniel2013).

Moral concerns about purity and harm

According to Moral Foundations Theory, disgust-related purity concerns play an important role in some policy positions (Koleva et al., Reference Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto and Haidt2012; Tilburt et al., Reference Tilburt, James, Jenkins, Antiel, Curlin and Rasinski2013). By contrast, the Theory of Dyadic Morality proposes that concerns about harm are the primary moral concern, and any seeming role of purity can be fully accounted for by harm concerns (Schein & Gray, 2018). Our results were most consistent with Moral Foundations Theory: purity was the strongest predictor of support for bathroom restrictions in every analysis, even after controlling for harm. This was true for both general concerns (as measured by the harm and purity subscales of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and Ditto2011) and concerns that relate specifically to bathroom restrictions. Importantly, purity was a significant predictor even after controlling for political conservatism. This suggests that the influence of purity on support for bathroom restrictions is not reducible to conservative orientations such as resistance to change and acceptance of inequality (Koleva et al., Reference Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto and Haidt2012; Kugler et al., Reference Kugler, Jost and Noorbaloochi2014).

Harm also predicted support for bathroom restrictions, albeit to a lesser extent. Those who were generally more concerned about harm were less supportive of bathroom restrictions, as were those who were more concerned about potential harm to transgender people. Those who were more concerned about potential harm to cisgender people were more supportive of bathroom restrictions. With that said, despite the prevalence of harm rhetoric among those who support bathroom restrictions (Fernandez & Blinder, Reference Fernandez and Blinder2015), opinions are probably more strongly driven by moral concerns rooted in disgust than by concerns about possible harm toward either cisgender or transgender people.

We also tested an important assumption of Moral Foundations Theory, namely, that purity concerns derive from the disease-avoidance system, and result in support for social policies that maintain purity (like bathroom restrictions). Consistent with this assumption, purity concerns mediated the effect of pathogen disgust on support for bathroom restrictions. This mediated effect remained significant even after incorporating a potential role for harm concerns.

Target identity: Trans men versus trans women

Much of the debate around bathroom policies seems to be concerned primarily with trans women (“men in women’s bathrooms”). We therefore conducted exploratory analyses to investigate whether support for bathroom restrictions, and the influences on support, differ depending on target identity—that is, whether people are prompted to imagine a trans woman using a women’s bathroom versus a trans man using a men’s bathroom. Overall, we found no mean difference in support for bathroom restrictions between these target identity groups. In other words, participants did not support bathroom restrictions more when they prevent trans women from entering women’s bathrooms versus trans men from entering men’s bathrooms. However, participants in the trans women group were more concerned about the safety of cisgender people than were people in the trans men group. With respect to the influence of different subtypes of disgust on policy support, we found that target did not interact with any of the disgust subtypes in predicting support for bathroom restrictions. Target also did not interact with either general harm or general purity concerns. Thus, in spite of the rhetoric regarding “men in women’s bathrooms,” the influences on support for bathroom restrictions seem largely the same regardless of the gender of the trans person being considered.

Limitations and future directions

Very little previous research has examined the role of disgust in attitudes toward transgender peoples’ rights (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Flores, Haider-Markel, Lewis, Tadlock and Taylor2017). Our research adds to this small literature by identifying which subtypes of disgust are most closely connected to bathroom access attitudes and by revealing that disgust-driven moral concerns play a central role in support for policies that restrict bathroom access. However, much more work is needed to address the limitations of our work and to pursue new questions arising from it.

We chose to focus on bathroom restrictions because of the prominence of this issue in the national debate about transgender rights. However, bathroom access is just one area of debate; other prominent debates revolve around access to employment, housing, and medical care for transgender people (e.g., Grant et al., Reference Grant, Mottet, Tanis, Harrison, Herman and Keisling2011). It remains to be seen whether disgust and disgust-driven moral values play the same role in issues beyond bathroom restrictions. Relatedly, we examined only a limited number of predictors of policy support. Other validated measures, such as the Attitudes Toward Transgender Men and Women scale (Billard, Reference Billard2018), offer greater conceptual coverage of attitudes toward transgender people and should be incorporated into future research.

We hypothesized that sexual or injury disgust would drive support for bathroom restrictions, given lay associations between transgender identity and gender confirming surgery (Tadlock, Reference Tadlock, Taylor and Haider-Markel2015). Although we did compare target identities (trans man versus trans woman), one limitation of this approach is that we did not address the issue of gender confirming surgery directly. Although we did not find evidence that sexual or injury disgust are particularly relevant to bathroom bill support, perhaps our stimuli were simply too noisy and indirect to elicit these disgust subtypes. If more extensive gender transitions violate mainstream social notions of normality and abnormality more strongly, then future research should specify whether, or to what extent, the trans man or woman has altered their body as part of their transition.

Lastly, while we measured concerns about harm toward cisgender people separately from transgender people, the scenarios in our questionnaire may imply that transgender people themselves would cause the harm. However, we did not specify who exactly would be doing the harming in our scenarios. Importantly, political discussion around bathroom restrictions sometimes centers on fear of voyeurism or assault by cisgender men who may take advantage of open bathroom policies (Lopez, Reference Lopez2016). Our research may have concealed an interaction effect between cisgender harm and target insofar as we did not provide participants an opportunity to express concern about harm caused by non-transgender people.

Conclusion

Although there is much work to be done, one clear takeaway is that social scientists and activists seeking to influence support for bathroom restrictions should focus on moral concerns around purity, as these were the most relevant to policy support in all of our analyses. While harm did seem important to policy support, our results indicate it would be relatively less helpful to point out that open bathroom access does not result in harm toward cisgender women and girls (Grinberg & Stewart, Reference Grinberg and Stewart2017). Instead, interventions (and arguments) that directly target disgust and disgust-driven moral concerns are likely to have a larger impact. One potentially promising approach is to simply increase familiarity with transgender people. Nonmoral disgust is heavily influenced by familiarity and exposure; for example, many people found sushi disgusting when it first entered Western culture, but this sentiment dropped away as sushi became commonplace. On the whole, though, not much is known about how to influence disgust-driven attitudes or about the influences of attitudes toward transgender-centric policies more broadly. These issues will be important avenues for future research.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/pls.2020.20.