The redrawing of the European political map in the second half of the nineteenth century did not leave the Romanian PrincipalitiesFootnote 1 unaffected. The 1859 union of Moldavia and Wallachia,Footnote 2 at the time still vassals of the Ottoman Empire, was the first step towards the creation of a modern nation-state – a lengthy process that was part of the larger European phenomenon that sought the construction of national identities that had hitherto been invisible, stifled under imperial domination. Under the leadership of Alexandru Ioan Cuza,Footnote 3 the United Principalities became a unitary state in terms of constitution and administration, and the area came to be known officially as Romania in 1862, playing the part of the young nation to the best of its abilities in the decades that followed. Cuza’s sweeping reforms in the areas of economics, politics, culture and administration ensured that the country would develop in a modern, pro-Western direction, but failed to assure him a lengthy reign. In February 1866, an alliance of the political parties concerned with the ruler’s growing authority – called the Monstrous Coalition in the press favourable to Cuza – forced him to abdicate in favour of Prince Carol of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen.Footnote 4 Proclaimed Prince of Romania on 10 May 1866 and King of Romania on 10 May 1881, Carol I, who ruled the nation for 48 years, would be inextricably linked with one of the periods of great stability in the country’s history. Carol’s prestige benefited considerably from his participation in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, where he personally led Romania’s forces on the battlefieldFootnote 5 and secured the country’s independence from the Ottoman Empire (see Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1 The score Marșul 1877 (March of 1877), by Constantin Dimitrescu (front cover)

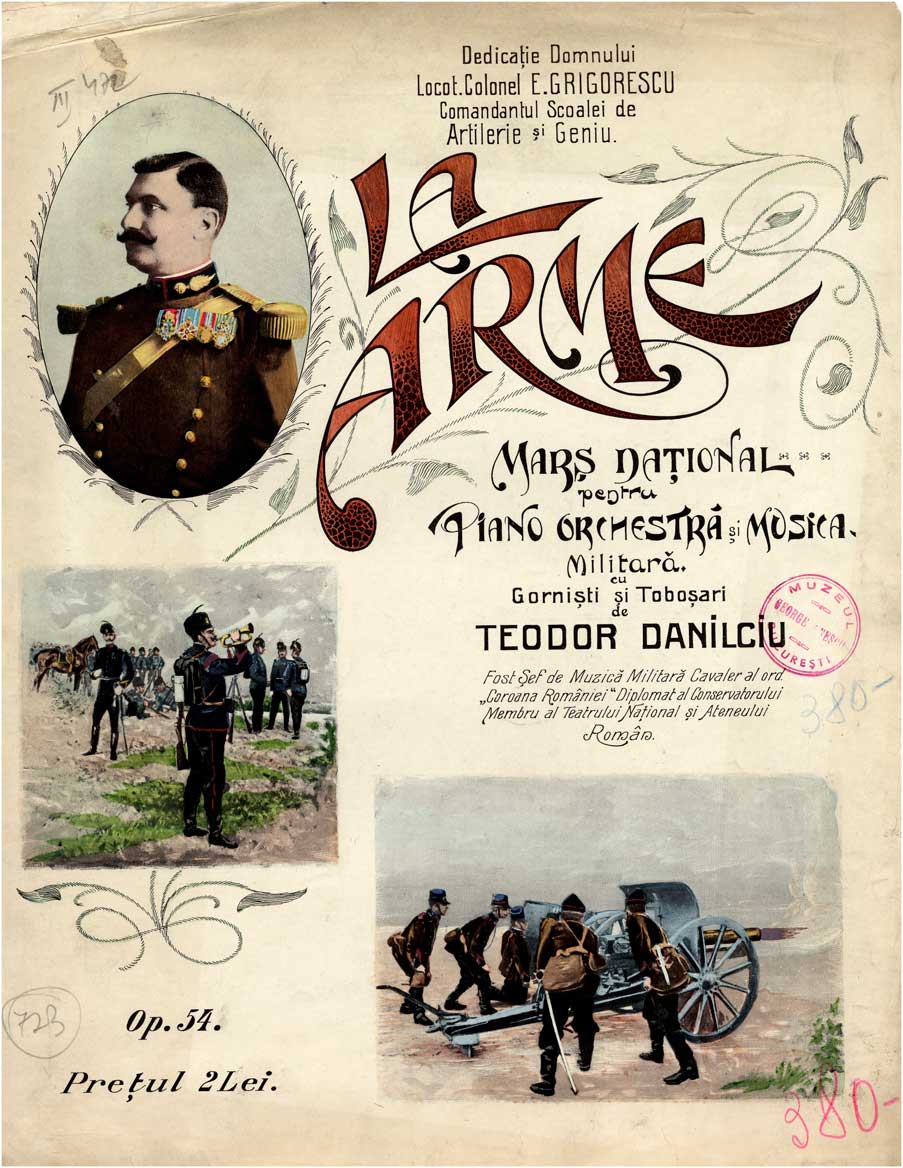

Fig. 2 The score La arme (To Arms), by Teodor Danilciu (front cover)

After events of such magnitude – victories secured not without loss of life – Romania no longer had other options: it had to build a modern ‘nation-state’, choosing Western countries as its models, a task which it undertook in all seriousness and with all of its resources. A major role in nationalist propaganda, which was adopted as state politics, was assigned to the press – including the specialized press of the late nineteenth century.

Musical publications – though few in number and published sporadically – reflected the spirit of the time. Unfortunately, the lack of a musical tradition reduced the few attempts of this kind to a clumsy and anachronistic pioneering activity, filled with unintentional humour. The awareness of belonging to a minor culture and, frankly speaking, of having a quasi-nonexistent musical culture at that time, coupled with the ‘high’ aspirations of romantic ideology (the idea of ‘genius’, the idealization of folklore, etc.) fuelled a particular style of writing music history, the characteristics of which will be analysed in the present study.

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, two widely different attitudes regarding local music were evident in the Romanian musical press. One had an obvious nationalist character, which took the form of an apologetic idealization of Romanian music – folk music in particular – but also of rousing calls for the improvement of composition and performance in the local music scene. The other attitude reflected a pronounced inferiority complex connected to everything that contemporary Romanian music represented. This was manifested especially in the (sometimes scathing) criticism of the Romanian music scene and in hostility to or ignorance of Romanian musicians, composers or interpreters, except when they attained success and recognition abroad – and sometimes not even then. The two extreme attitudes were not mutually exclusive, but fed off each other; essentially, they worked in what might be understood as a cause and effect relationship.

Over the course of just a few years, general arts magazines such Eco musicale di Romania (1869–71) – one of the first specialized publications in Bucharest, writing in support of Italian opera – were replaced by a specialized press focused on national music. The publication that signalled this direction and subsequently became famous for its militant, nationalist character was Lyra română – foaie musicală şi literară, a weekly magazine published between 2 December 1879 and 31 October 1880.

In its 39 issues, Lyra română firmly followed the direction described in the Foreword to its first issue, written by ‘The editorial board’. This was a nationalist programme, purely propagandistic, but drawing on Western music as a point of reference. Here are a few fragments:

Music is one of the strongest elements of civilization. One can easily notice that it is mainly disseminated in countries which enjoy a more advanced civilization. Thus, Italy and France are far superior in music to other countries where civilization is less developed[,] and we could mention Germany where sonatas, symphonies and the highest expressions of music have become almost popular. … We … in those circumstances, couldn’t surpass the limits of folk music and advance towards true art [Western art]. But, if it’s true that we are a nation fit for civilization … it is our duty to open the gates that lead towards art.

…

What we desire and claim to do through this paper is … to place the horn in the hand of those who wish to sound the alarm for the awakening of our national music. …

Hence, Lyra română attempts … to focus particularly on issues of music which regard our own nationality, originality and genius. …

Lyra română will offer basic knowledge and reveal the secrets of this art, telling its history and providing the biographies of its most important apostles; it will bring their works to light and analyse them both from a general point of view, as well as in relationship with history and the reforms and innovations they enabled.Footnote 6

The programme thus announced was consistently followed. Generally, a balance was struck between writing on Romanian music and examining ‘universal’ music. Consequently, each issue contains both materials focused on local subjects and articles about European music – mostly biographical portraits of great composers: Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, Haydn and so forth. The magazine also emphasized its didactic character, as was the custom in Europe at the time, by publishing in serial form fragments from A General History of Music by François-Joseph Fétis. In fact, Lyra română addressed a large and diverse audience – in tune with the romantic ideal of popularizing culture: ‘We will always think about all social classes which Lyra română is determined to address.’Footnote 7

A few ideas launched in this Foreword were to be found ten years later in another magazine, România musicală, which appeared twice monthly between 1 March 1890 and 28 December 1904. This publication also aimed at ‘developing Romanian musical art’, but instead of tackling folk themes, as Lyra română did, it focused on the debate around cultured music:

We who’ve taken on the task to reveal the state we’re in, both morally and intellectually with regards to our musical art … are determined to support … this long-discriminated-against art and to show what the true causes are that hinder the development of musical art.Footnote 8

Like Lyra română, România musicală focused on the musical and cultural education of the masses, publishing in successive issues fragments from ‘Music Treatises’ by Napoléon Henri Reber and Ernest Friedrich Richter, among others.

The writing on Romanian music in the two magazines focuses on three categories of composition: ‘folk’, ‘religious’ and ‘cultured’. Each of these is treated in with critical discourse involving, in different proportions, the two antagonistic attitudes: the apologetic one, affirming so-called ‘Romanian’ superiority, and the profoundly dismissive one, contesting the value of anything ‘Romanian’.

‘Folk’ Music

In articles about so-called ‘folk’ music – the expression used in such magazines for traditional, rural music – a strongly nationalist tone can be discerned. Folk music, in their opinion, is connected to the idea of ‘nation’ more than any other type of music, and so it becomes the preferred vehicle for propaganda: it serves as an expression of the nation’s ‘genius’, as a pretext for configuring an avant la lettre protochronism or as an example of how folklore can be counterfeited for political reasons.Footnote 9 (A similar type of rhetoric, which is essentially romantic – imbued with idealism and sentimentality – would later be used by both inter-war fascist and post-war communist propaganda in Romania.)

To be more precise, in the pages of the two magazines, a few idées fixes were sketched, periodically reiterated and developed more or less convincingly by authors whose names are now forgotten. It is unclear how much fame they enjoyed even during their lifetimes, as some of them signed their articles with initials or pseudonyms (P., Don Remi, R., etc.).Footnote 10

The detailed treatment of ‘folk music’ resulted in numerous studies, usually published serially, in consecutive issues of the magazines. What immediately strikes the eye is that ‘folk music’ and ‘national music’ are taken to mean the same thing, as becomes apparent from the titles of works dedicated to anonymous peasant music: ‘A Few Ideas about National Music’ or ‘Romanian National Music’.

The Dilemma of the ‘National Character’ of Music

The problems that appear to preoccupy the authors of these texts can be summarized in a few questions: Is there a Romanian ‘national’ music? Can we talk of specific ‘characteristics’? If so, what constitutes the ‘national character’ of music and what are its determining factors? In fact, all of these questions represent false dilemmas, as the ready-made answers that are put forward are constructed according to the logic of propaganda and often ignore proper musical arguments.

For instance, Gheorghe Missail,Footnote 11 though recognizing the debate surrounding the existence of a ‘Romanian national music’, embraces the romantic idea of ‘national identity’, without taking into account the arguments of the other camp:

Many claim that Romanians don’t have a national music. Others disagree. We are the latter. … Romanians have their national music. It is natural that every country should have its songs, according to the land and the character of its inhabitants.Footnote 12

To support his claim that ‘every nation has its own music’, the author surveys – with a nonchalance that is now difficult to understand, but that was symptomatic for the ‘era of nationalism’ – the ‘national music’ of various countries:

Swiss national music has a monotonous melody, devoid of energetic accents. Russians have a tuneful, but sad music. Poles are very similar to Russians, except for a few nuances. Their music is more joyous, but more spiritual, more belligerent. English music is sad, monotonous, devoid of inspiration and melody. Scots have a monotonous, sad and weeping melody which foreigners like. The Chinese have a harsh and monotonous music that is similar to their language.Footnote 13

The existence of a ‘Romanian national music’ is also accepted as an axiomatic fact by Toma Ionescu,Footnote 14 another author who wrote for Lyra română. He rejected as ‘absurd’ the opinion that Romanians don’t have their own music and, with the same patriotic impetus, did not tolerate the hypothesis of influences from neighbouring countries. Ionescu’s justification that similarities come from common historical conditions and common psychology leads his argument to a logical contradiction: after he concludes that Romanians have their own music, he also claims that ‘Romania should express its emotions through the same type of song’ as other East European peoples:

Romanians have been singing as their heart commands for over 18 centuries and despite this, there were strangers that denied the existence of national music …. If there were people that completely denied the existence of our national music, there were others that … admitted the existence of our music, but recognized numerous influences from other peoples. We can support neither the first, nor the second opinion. We reject the first one as being absurd, since no nation can be denied the gift of singing its joys and sorrows ….

As for the second opinion, we cannot accept it either. Our national music isn’t influenced by the music of neighbouring peoples. … Sorrow did not find a better place in Europe than in the Orient. … It was only natural that a similar character would have been formed. Romania … had to express its sentiment through the same song. Thus [sic], … we reject the second opinion as well.Footnote 15

When ‘foreigners’ validated ‘Romanian national music’, through word or deed, the press enthusiastically pointed out those occurrences, especially if they were put forward by figures in the field of music (Franz Liszt,Footnote 16 Carol Miculi) or literature (Jules Claretie, André Theuriet, Em. du Bertha). For the authors of the articles the unequal importance of these figures doesn’t seem to matter; ‘foreigners’ willing to take Romanian music into account are embraced, according to their efforts in this direction. This is why Carol Miculi, for instance, is very famous in Romanian historiography:

I have met many travellers – writes Carol Miculi, important artist, distinguished student of the famous pianist Chopin and connoisseur of Romanian music – foreign travellers in the Romanian countries, who confessed (even though they were not romantics) that these simple, expressive songs impressed them more vividly and profoundly than all the throbbing nonsense which can be heard in today’s concert halls … and are received with frenetic enthusiasm.Footnote 17

By bringing into discussion the Western acknowledgement of Romanian music, the authors aim not necessarily at clarifying aspects of the history of music, but at awakening the feeling of national pride. In their propagandistic mission, the authors address Romanians directly, imperatively, assigning them responsibilities.Footnote 18 Thus, cultivating the national ‘treasure’ – folklore – becomes a collective duty, while the ignorance of Romanians towards such music is equated with a ‘crime’. The manipulation operating through words such as ‘pride’, ‘goldmine’ and ‘crime’ is as transparent as can be:

our national music must be a source of pride for us, because it is something that we can promote abroad; but we should cultivate it and not let it perish, as we are starting to do, and thus committing one of the basest crimes: a crime that we cannot excuse, that will not be forgotten by history and the world, who found a goldmine in our music whenever it heard it.Footnote 19

The problem of the ‘national musical character’ also sparked debates in the musical press. Although they enthusiastically admitted the existence of such a ‘character’, musical journalists struggled with the difficulty of defining or describing it. The abundance of adjectives offers no solution, but rather renders vague and obscure any attempt to define Romanian music precisely: ‘Our folk music is sweet, delicate, melancholy and belligerent at the same time; fiery, passionate and filled with talent. All the feelings of Romanian hearts are truthfully reproduced in it’.Footnote 20

Such successions of attributes, far from exhausting the discussions of ‘character’, merely help to reveal the authors’ true intent: the outlining of a national aura. In trying to justify some features as essential to the ‘Romanian musical character’, the authors employ well-known clichés reminiscent of any nationalist rhetoric: the mythologization of history, the idea of a national destiny yet unfulfilled, the idealization of the Romanian peasant as a genius (of the people) and so on.

Music and the Mythologization of History

A central pillar in the nationalist discourse on music is historical reference:

The noblest feelings of the soul are awakened and revealed at the sound of a simple melody if that melody is tied to a historical memory. There is an intimate connection between national arias and memories of the past, like the one between cause and effect.Footnote 21

Yet in the context of the time, music became a pretext for diatribes on the theme of the ‘tumultuous’ past of the Romanian people:

What could be the cause of our melancholy and sad music? … Whoever opened the great book of the Romanian people must have been touched by the array of misfortunes that haunted this people of martyrs. From colonization to our present times … peace hasn’t reigned over the blessed land of Romania.Footnote 22

Commentators placed at the forefront of their historical inquiries a symbolic phenomenon of the past – the origins of the Romanian people – speaking almost religiously of the colonizing of Dacians by Romans (in the first and second centuries CE). From their discourse, the relationship between this historical process and Romanian music would seem to be a causal one, with very simple, self-explanatory mechanics. The intention doesn’t seem to be to clarify the dynamics and development of music, but rather to attribute to it an important role in the formation of the nation; not coincidently, the authors of the articles strongly support the millennia-old existence of Romanian music – ‘a dear heritage from our ancestors’Footnote 23 – and the belief that ‘national music’ and ‘Romanians’ have the same age:

This type of music is the oldest one. As soon as the fusion between Dacians and Romans was finished, national music was born. … Thus, for us Romanians, as for any other people, folk music or more precisely national music is as old as the Romanians.Footnote 24

Being a Latin people presupposes a natural predilection for music, Gheorghe Missail claims, in a reference that concerns Romanians and Italians, including the illiterate peasantry: ‘In the mountains and valleys of Romania, as well as Italy, most peasants don’t know how to read; however, they all sing lyrics from dusk till dawn’.Footnote 25

Missail’s reference to the Latinity of Romanians raises an important aspect of the discourse, and calls for clarification and examination in terms of the issue of ‘national identity’. According to the Missail, a common Latin origin must not be understood as a dilution of identity – either linguistic or musical – and, to be more persuasive, he establishes an analogy between the two: ‘Although French, Italian, Spanish and Romanian people have the same origin, eternal Rome, their languages are different … and also their music’.Footnote 26

Another aspect connected to history is represented by the ‘harsh conditions’ and ‘suffering’ endured by the Romanian people throughout time, which undermined the evolution of music in a ‘civilized’, Western sense. The frequent invocation of damaging historical factors usually served as an excuse for the lack of a cultured musical tradition. Otherwise, articles were filled with a rhetoric of great expectations, of hope regarding the development of local cultured composition. Its chance of becoming valuable and redeeming was itself predicated on choosing folklore as a source of inspiration:

Romanian music, as well as Romanian poetry, is an eloquent mirror of national history. Graceful images, deep knowledge, everything is found in these melodies, created by these people, whose destiny has not yet been fulfilled. The poet and national artist finds in our arias a treasure of inspiration. …

When will this rich goldmine be exploited properly? When will our liturgy, theatre and opera have their own characteristic features, a physiognomy imprinted with the national idea that will be a harmonious reflection of everything noble and uplifting in the Romanian character?Footnote 27

In articles about ‘folk’ music, connections were frequently made between the idealized past and the problematic, corrupted present. For instance, Gheorghe Missail refers to a ballad that describes how ‘a state criminal is exempted from the death penalty and made a royal son-in-law only because he knew how to play the kobsa (or Thracian lyre) very well’.Footnote 28 The event – which is most likely apocryphal – was said to have taken place during the reign of Stephen the Great. What conclusion does Missail reach after invoking this ballad?

One can see that old Romanians were more cultured than modern ones …. Nowadays, in the same country, you could be a Cadmus, Orpheus, Liszt, Verdi, Donizetti or Chopin, but if you are Romanian, you will perish if you don’t know how to flatter the menial passions of people and especially if you can’t bow to the people who run the country. As you can see, things are regressing rather than progressing. Civilization has entered the sign of the Cancer.Footnote 29

Further, Missail argues that the references to the figures of outlaws depicted in ballads (a type of local Robin Hood) offer true models – perhaps for the politicians of the time – of benefactors, protectors of the poor and defenceless:

The Romanian thief maintains an aura of poetry that is reflected in some ballads such as Codreanu, Bujor, Tunsul, Jianul, where the Romanian bandit is depicted as scorning death and being faithful to his lover … loving good horses … the folk poetry of our century presents all thieves as natural defenders of oppressed peasants.Footnote 30

Lyrics (for instance, from the ballad Darie, the bandit from Bukovina) are indicative of the moral stature of these ‘outlaws’:

And when I filled my bags / Many villages I visited / Giving money to the poor /And keeping very little for myself.Footnote 31

Folklore as a Product of ‘National Genius’

Not only are certain figures of the past idealized in these articles, but so is the ‘Romanian peasant’ himself, in general, as a collective, anonymous character. Thus, references can be found to the ‘genius of the people’,Footnote 32 which produced ‘original’ works,Footnote 33 carefully transmitted from one generation to another:

From one generation to the other, from father to son, they [Romanian folk tunes] were left as heritage …. Every family preserves with the greatest sanctity, alongside the ancient traditions and the fantastic stories of legendary figures, its national songs.Footnote 34

In this attempt at idealizing and mythologizing the Romanian peasant, the Romanian woman attains a special aura, in the spirit of archaic, primitive cultures. She is seen as a symbol of fertility, as the only one who can assure the continuity and eternity of the Romanian nation, but also of this collective ‘given’, musical folklore:

Romanians love music and they’re always ready to sing. Romanian women in this sense are superior to men. They are the true Romanian bards; the true vestals, who protected and redeemed national music and poetry, singing and re-singing them to their children.Footnote 35

This evocation of womanhood in no way reflected the social condition of nineteenth-century Romanian peasant women, who were actually considered to be almost subhuman – strictly inferior and subordinate to men. The romantically inclined intellectual placed her on a pedestal, where she had a clear and precise function: to transmit and perpetuate ‘the genius’ of the nation’s artistic production.

Closely connected with the idealization of the rural environment, the alienation of modern man from his country roots and their creative output was seen as an imminent danger of perversion and displacement:

Who still goes to the countryside? Who degrades himself in order to get in touch with the people? … How would this country be if peasants threw themselves in the vortex of estrangement and indifference, where us city dwellers have thrown ourselves? God forbid!Footnote 36

Manipulation by Counterfeiting Folklore

The Romantic discourse of the simple peasant and his wife doesn’t stop here, but reaches different degrees of refinement. One example is the projection of the ideals of the 1848 generation (which had been adopted by the following generation) onto the Romanian peasant. Key to this is the manipulation of counterfeit folklore. Lyrics created in folk fashion were attributed to Romanian peasants. The evidence of forgery isn’t difficult to discern in these lyrics: the illiterate peasant is attributed serious knowledge of ancient history and geography, but more importantly of the ideal of ‘uniting the Romanian Principalities’ and ‘recomposing the nation’ – an ideal adopted by the revolutionary intelligentsia of 1848. Counterfeiting Romanian folklore as a means of political manipulation was not exclusive to the nineteenth century, but is also found in the twentieth century, starting with the 1950s, when it became a large-scale tool employed by communist propaganda in yet another version of Romanian nationalism. Here are a few samples of counterfeit folklore quoted in late nineteenth century publications:

Alas, my dear, if I wanted / … / The entire Dacia I would plough / I would plough and avenge / The news would spread / From Hotin at the Danube / To Pind in the Carpathians / Where I have brothers and sisters / Scattered from Mother Rome / By foreigners embittered / By people and heavens forgotten. / But God is good / And I’m a brave Romanian / My time will come / And in one year I will reunite / Trajan’s kingdom.Footnote 37

Also connected to folklore, another form of manipulation consists in claiming the superiority of Romanian folk creation, in comparison with any other type of music, including European cultured music (!). To suggest this superiority Missail turns to the aesthetics of Hegel. Missail suggests – in an inadvertently comic manner – that Hegel’s ‘philosophical-musical’ thinking suffered from a lack of knowledge regarding ‘our national dance and music’:

According to Hegel, the spirit, when confronted with beautiful music, loses its contemplative freedom. Musical expression attracts and spirits us away, the sound works as an element, as a force of nature. …

And despite this, the respected scholar has never seen the choreographic exercises of Romanians. Many philosophical-musical reflections would have germinated in his powerful mind if he had judged de visu et audictu our national dances and music!Footnote 38

Press comments on Romanian folk music praised fiddle players, who ‘made a profitable occupation out of preserving and spreading these songs’.Footnote 39 In the same nationalist vein, stressing the multi-millennial existence of everything Romanian, fiddlers were attributed the same immemorial age: ‘Accompanied by a violin, kobsa and pan flute … they went to every house and every village, enchanting our ancestors with their songs’.Footnote 40

Despite the amplitude of serialized articles dedicated to musical folklore, the styles and genres are approached in a superficial manner. An excuse for the authors of these articles is that the available information regarding this type of music was limited; for instance, one description of the folk music repertoire, which is both incomplete and ambiguous, is based on Carol Miculi’s classification:

Those that sing of longing and sorrow or that recount historical facts are called doinas or ballads, those that show momentary feelings or passing whims are called worldly songs or romances and finally, those that express the joy of the Romanians when they reject misery are called dance songs.Footnote 41

Also of interest are the polemics on folk music collections, which were relatively numerous. These had been compiled before this period by relatively well-known Romanian musicians: Josef Herfner, Franz Ruzitski, Ioan Andrei Wachmann, Constantin N. Steleanu, Alexandru Berdescu, Teodor Burada, Eduard Wachmann and others. The flaws of the musical collections are generally observed pertinently, with a clear eye:

They [the melodies noted in the collections] don’t seem to be Romanian national arias. Almost all collectors attempted to redo them according to musical rules and their fantasy. They transmitted them as they should have been according to the rules, not as they actually were …. They failed to notice that natural beauty fades when the artist seeks to modify it according to classical rules.Footnote 42

Such plausible observations – which also included reproaches of faulty transcriptions for piano or voice accompanied by piano – could only have had a positive impact on the objective research of musical folklore, as much as it was possible.

Religious Music

In the written press of the last decades of the nineteenth century, religious music proved ideal for political use, being exploited perhaps even more efficiently than folk music. How can the interest in religious music be explained, a type of music which ‘isn’t a creation of Romanian genius, being common to all nations of Greek Orthodox religion, such as Greeks, Russians, Serbs, etc.?’Footnote 43 The answer is fairly straightforward: one of the reforms initiated by Prince Alexandru Ioan Cuza had sought to thoroughly modernize this type of music. It was connected with the secularization of church property (1863) and the replacement of Greek with Romanian as the official language of worship, and it consisted in the substitution of Byzantine chants (referred to as ‘psaltic’ or ‘oriental’ music in the contemporary press) with so-called ‘systematic’ music (by which was meant Western choral music). The reasons for this reform ultimately lay in the new political direction Romania was to follow, which meant that the country had to distance itself from the Greco-Turkish Orient, to deny its Balkan affiliation, and to embrace Western values. The very substitution of church chants took on propagandistic significance:

The Great Cuza, in his burning desire to clothe our country in the garments of Western civilization as soon as possible decided, among the other reforms he undertook in the different state institutions, to improve the church as well. He thus decreed the gradual removal of psaltic chant and its replacement with choral music. Hence, under the auspices of this great ruler, after the secularization of church property, choirs were formed at the churches whose belongings had been taken over by the state.Footnote 44

Cuza – the ever-efficient administrator – had personally supervised the implementation of this reform. He had disbanded music schools near metropolitan centres and bishoprics, whose professionals were forced to find employment elsewhere. Studying Byzantine music was out of the question at the newly founded Conservatories in Iaşi (1860) and Bucharest (1864). On 18 January 1865, Cuza had appointed a certain Ioan CartFootnote 45 as professor at the Bucharest Conservatory, ‘with the mission to instruct all singers from the capital’s state churches in the knowledge of the principles of systematic music and to form small choirs of duets, trios or quartets’.Footnote 46

Nationalist-Orthodox Propaganda

It is quite interesting that although Cuza’s reign ended in 1866, his reform in the field of religious music was successfully continued in the decades that followed. Those who tackled the subject of religious music in the press of 1880–90 did not shy away from declaring their admiration for ‘the Great Cuza’, and they tailored their discourse in support of the direction laid out for religious music by the former prince.

As a consequence, these authors resorted to a complex and multifaceted propaganda arsenal: both religious, intended to show the superiority of the Orthodox Church in comparison with other confessions, and nationalist. Here is how the Romanian Orthodox church is described:

It cannot inspire the horror and disgust that Catholics and Protestants spark, because it hasn’t been a source of hatred and war among brothers, but a centre of peace, love, union and brotherhood. Moreover, it has fostered and developed our national sentiment.Footnote 47

Journalists felt compelled to illustrate, whenever they could, the strong connection between the Orthodox Church and the creation of the Romanian nation; for instance, Toma Ionescu, who was an expert in the field, compiled a list of priests, bishops, metropolitan bishops and others who ‘have stood at the forefront of the national movement and have contributed to the emancipation and rebirth of the Romanian nation’.Footnote 48

The nationalist discourse on religious music strikingly resembles that on musical folklore. The references to a ‘glorious’ past, starting from the colonization of Dacia, are familiar. This time though, they serve the even stranger attempt to pretend that there was a local Christian music two centuries before the legislation of Christianity in the Roman Empire – in 313 AD, during the rule of Emperor Constantine, through the ‘Edict of Milan’. (The protochronistic hypothesis that claims that Romanians were one of the first peoples of Europe to be Christianized, which Toma Ionescu seems to support in his article, is a legend – of the time? older? it is difficult to tell – maintained even today by nationalist-orthodox propaganda, with no literary, historical or archaeological proof.) Convinced that Dacians converted to Christianity immediately after they had been conquered by the Romans, the author of the article claims, with a hint of regret, that had there been no ‘barbaric invasions’ and if ‘peace … had reigned in Dacia … religious music would have made progress’.Footnote 49 Regarding music in Dacia, he doesn’t risk stating an opinion and is content with a truism: ‘The manner of singing, as well as the songs … of religious music … are lost in the annals of history.’Footnote 50

Between this foray into the distant past and Cuza’s reforms, the author establishes a few other milestones in Romanian history. Time and time again, he accusingly points at obstacles that hindered the assertion of nationhood, of the Romanian language and, implicitly, of a religious music in Romanian. Thus, after he laments over the ‘subjugation of the country in the linguistic field’Footnote 51 through ‘slavonization’ (a process begun in the fifth century CE and continued for over a millennium), he moves on to a more recent historical stage, that of the Phanariot domination (which lasted from 1711 to 1821). The references to that period, when some PhanariotsFootnote 52 were named rulers of the Romanian Countries, Moldavia and Wallachia, are made in a truly pathetic rhetorical style – a sign of its freshness in Romanian consciousness:

Upon hearing this fatal word [Phanariot] Romanian flesh shudders, the son screams in the mother’s womb, as it reminds us of the time of humiliation and death when our entire political and social edifice was almost destroyed. The Greek-Turkish merchants from the Phanar are raised upon the mighty thrones of Mircea and Ştefan and speak Greek. They shut down national schools ….Footnote 53

The Persecution of Byzantine Music

The fact that Phanariot influence is seen as a terrible affliction that hindered the development of Romanian nationhood is projected onto the religious music practised by the Greeks: Byzantine chant. Eliminating this style of music from the Romanian church was also the main aim of Cuza’s reform:

Due to his great, but legitimate hatred towards the Greeks, [Cuza] wanted, besides the introduction of Romanian language in the church, to eliminate the old oriental music and replace it with Western music …. By introducing systematic music, the progress of religious music was assured.Footnote 54

The propaganda in the press in support of Cuza’s reform involved, on the one hand an aggressive campaign against Byzantine music and, on the other hand, an often-undeserved attention given to newly formed choirs and their repertoires, which were conceived in a more or less Western fashion.

The authors seem to try to denigrate Byzantine music as much as possible by labelling it anachronistic and out of step with what they call ‘the musical impetus of our people’:

Everyone knows that the mission of these church choirs is to replace the monotony of oriental music, which was sung with the hoarse and nasal voices of singers who led the hearts of believers astray during the divine service. Instead of piety, they were instilled with a certain amount of disgust towards the holy church.Footnote 55

Or:

This music … because of its low musical value and defective manner of interpretation and execution corresponds neither with the purpose it was meant for, nor the requirements of our century. … Everybody knows how difficult it is to hold back your laughter when you see a priest that makes all sorts of faces in order to sing a heirmos [the initial lyric of a religious chant] nasally and with an undulated voice.Footnote 56

Exceptions are made when Byzantine music is valued because of its association with remarkable personalities such as Anton Pann,Footnote 57 who excelled at this type of music (among other things):

All the religious musical writings of Anton Pann are filled with beauty, written with craft and embellished by a fruitful inspiration. … Anyone who wishes to study the cultural development of psaltic music in our country cannot make a successful study without researching and analysing Anton Pann’s writings.Footnote 58

The alternative to ‘oriental’ music is represented by choirs, whose pro-Western direction is understood in a naïve, rudimentary and superficial manner: ‘Civilized peoples such as the French and especially the Germans, convinced by the importance and necessity of [choral music] have introduced it in their churches a long time ago and have had very satisfying results.’Footnote 59 To prove his point, the author names a few ‘geniuses’ such as Bach, Haydn and Mozart, who ‘were formed through religious music’.

A decade and a half after Cuza’s reform, an overview of the situation of church ensembles in Bucharest, proposed by Toma Ionescu, doesn’t seem very appealing: the false intonation, the defective beats, the negligence and lack of taste in choosing the repertoire are the most important aspects observed, and they are blamed mainly on incompetent conductors (sometimes named in those positions without having any musical studies). For instance, on the choir of Mihai-Vodă Church he notes:

When you shout you don’t pray, you threaten. And his Highness [the conductor], during the service, threatened God with songs that were made for praying. [In the piece Like the Emperor] the tone was too high, and the piece already contained high notes for all voices, so the choir screeched so badly one wanted to run away.Footnote 60

Ionescu also criticizes the repertoires. At the Curtea-Veche Church, he notes, the repertoire ‘is still the antiquated one. Thus, most pieces are Russian – the same songs that our choirs sang when they were first formed.’Footnote 61 And at St Gheorghe Church ‘they take foreign pieces and apply lyrics from our liturgy on top of them, but the words aren’t suitable. … This is how I heard some ektenias taken from Ruy-Blas Footnote 62 which lack all religious character’.Footnote 63 These observations are a source of true discontent for the Ionescu, who had expected to hear a lot more original Romanian compositions in church choir performance. After the start given by Cuza’s reform, the decade-long support – including through a constant promotion in the press – offered of the choral direction in religious music had a considerable effect on developing a Romanian choral tradition, which was successfully continued in the twentieth century.

Cultured music

In nineteenth-century music, the so-called ‘national schools’ (Polish, Hungarian, Norwegian etc.) enjoyed a special visibility, gaining international renown under the impulse of romantic ideology and in the context of the political affirmation of their respective states. It didn’t matter – terminologically speaking – that in most cases, these ‘schools’ had just one famous representative, who was mostly educated in Western schools.

Awaiting a Romanian Chopin

Romanians had also dreamed of a ‘national school’, but no Romanian Chopin or Liszt had appeared. How was local composition reflected in the press at the end of the nineteenth century? Essentially, anything that was written on original Romanian music can be summarized in two words: frustrated expectations.

Although all the discussions led to the problem of composition, journalists also explored peripheral matters, trying to depict a complete musical landscape. Some aspects – realistically presented – are used as excuses for the lack of musical personalities of a European calibre. The invocation of mentalities connected to the profession of musician, deeply rooted in Romanian society, offers such a justification:

It’s true that for us, since ancient times, music and other fine arts were only cultivated by foreigners and it was humiliating for our boyars to see their sons grabbing the violin bow, saying that it is a job for Gypsies; … or against morals to let their daughters embrace a theatre career … the scene being the field of depraved women.Footnote 64

The contemporary Romanian music scene is sketched in the colours of a bad provincial painting, and any comparison – including ones with the ‘humble villages’ of countries with a musical tradition – proves disadvantageous:

Not only in the greatest city centres, but also in the humble villages of Germany, France or Italy, choirs, opera arias, romances are sung; music is played in churches, in schools …. But for us, music seems to be completely frozen. … Indifference reigns, a fact that can be blamed on our social classes, a numbness which disappears only from time to time through the mask of bravado. A certain lady goes to the opera only to say she was there, while displaying her embellishments; if you ask her what aria she liked or who performed it better she will just say: beautiful.Footnote 65

Things don’t seem to have changed ten years later; the inferiority complex is as strong as ever – as can be observed in the pages of the magazine România musicală:

We’re much lower than where we should and could have been. It would be ironic to compare our country to France or Germany, who have a centuries-old tradition, but I believe that the few elements we possess could help create something better.Footnote 66

The difference – as opposed to the lamentations of the last decade – is that a culprit is sought in this instance:

Who could we blame for all these? We mainly think that the current school, the wretched and detestable system where music is taught bears the largest part of the guilt. … What are the fruits of our Conservatory after 26 years of activity? What are the works done by the former students of this school? Maybe you want to answer by pointing towards the music shops filled with dances of all sorts, which display on their first page painted faces and dedications and on the others, mistakes against the most elementary rules of composition.Footnote 67

Eduard Wachmann, in his role as director of the Music Conservatory in Bucharest, became the main target for România musicală magazine; he was blamed for the low quality of graduates – both composers and performers.Footnote 68

A Foreign Critic? Perhaps … ‘a Madman’

What is interesting is that, although Romanian journalists constantly criticize the situation of local music, they over-react when a foreigner dares to do the same thing. It doesn’t matter if his opinions resemble their own; any ‘outside’ criticism generates a wave of local indignation. This is what happened, for instance, when the musical magazine Berliner Signale published an article signed by Dr Emil Kolberg (Vienna) entitled ‘The Musical Situation in Romania’. The article was also published in its entirety in România musicală. Here are a few fragments:

The central musical institution in Romania is the Bucharest Conservatory. Its staff included an experienced pedagogue, director Wachmann (Bohemian by birth); recently, the excellent German artist, the violin virtuoso Carl Flesch and the violinist Dinicu, who have made their reputation through local success; besides these, only insignificant professors … well-paid and of inferior disposition …. Abroad, Romanian artists that studied in their own country are unknown.Footnote 69

The text caused a chain reaction: professors assigned C.M. Cordoneanu (the editor-in-chief of România musicală) to contact the Berlin magazine and ask for an explanation regarding the article. Then, the author needed to be identified, as well as the people he met in Bucharest. Such an event shook the Romanian musical scene out of its lethargy, sparking nationalist and sometimes xenophobic attitudes in the press:

Until we receive an answer, we shall continue to search for the source of these infamies – the author of the article being a foreigner – to expose and stigmatize him as he deserves. And we Romanians should learn from this, to be less generous with those strangers that come and beg for our bread and mock us after we give it to them.

After months of debate, the scandal reached its climax – a much more aggressive conclusion than the ‘injurious’ article itself:

How could he afford such criticism, a man who spent very little time in Bucharest and who met with no one in competent musical circles! Only unfounded allegations, personal fantasies, insulting alterations … and if we declare Dr. Kolberg a simple madman, we must be surprised that Berliner Signale accepted this infamous article.Footnote 70

‘Simple madman’ or not, Dr Kolberg had not heard of ‘Romanian artists that studied in their own country’. However, he had surely heard of a few performers who studied in the West. They were the first Romanian musicians who attained international acclaim and were appreciated by contemporary publications with a pronounced national pride. The singer Elena Theodorini was one of the first to break the ice; the magazine Lyra română published her photo on the first page, with the title ‘The first Romanian singer at the Italian Opera’ and a biography – thus interrupting the series dedicated to great composers. Moreover, the editorial board wrote her a poem, in which obsessively nationalist fixations are front and centre:

Mândră fiică a Olteniei, adorată cântăreaţă,

Cu-a ta artă majestoasă ne-ai purtat printr-altă viaţă

Şi-ai adus o mare fală scumpei noastre Românii

Proud daughter of Oltenia, adored singer, / With your majestic art you transported us to a different life / And brought great fame to our beloved Romania.Footnote 71

In addition to Elena Theodorini, the press noted the success of other valuable Romanian performers, including Hariclea Darclée (soprano), Demetru Popovici (baritone) and the pianists Constanţa Erbiceanu and Aurelia Cionca. Romanian composers, on the other hand, failed to keep up with these performers, and attracted a less than friendly attitude: ‘If we ask ourselves which are the composers that try from time to time to enrich our music, we must admit a sad truth’ – writes a journalist – he/she ‘barely plays the piano or violin’, writes a melody ‘with one finger’ and then sends it to be harmonized by ‘some masters such as Flechtenmacher, Wiest, Schipek, Ştefănescu’ (see Fig. 3).Footnote 72

Fig. 3 The score S-o vezi mamă, n-o mai uiți (Once you see her, mother, you won’t forget her), by Francois Schipek (front cover)

However, it is true that there were some reference points in contemporary music – a series of second-rank composers, without any chance of international promotion, but who earned the respect of Romanians by honestly practising their craft. (Paradoxically, many of them were not ethnic Romanians.) The main figure is that of Alexandru Flechtenmacher, sometimes described as a ‘genius’ of national music:

To talk about him is to write the history of our national music … He is the first who understood our national music, who through his genius knew how to strip it of its foreign elements and return it to us, so that everybody else can see the difference between our music and that of neighbouring regions.Footnote 73

Other appreciated names include that of Carol Miculi, an ‘erudite musician’ who studied at Vienna, where ‘besides the composition and counterpoint classes he successfully attended the piano classes of the famous Chopin’,Footnote 74 Eduard Wachmann (see Fig. 4), ‘son of the famous Romanian composer [Ioan Andrei Wachmann], the current director of the Bucharest Conservatory and the most erudite musician in the country’Footnote 75 and Gavriil Musicescu, harmony teacher at the Iaşi Conservatory, ‘primarily a composer of religious music’.Footnote 76

Fig. 4 The score Cântări religioase (Sacred Canticles), by Eduard Wachmann (front cover)

Except for the (few) references to these composers, most of the musical journalists hoped for the emergence of a providential figure for ‘national’ composition, capable of making the jump to ‘universal’ acknowledgement:

Where are our masters? What names illustrate Romanian musical art? We’re not talking about performers. Our masters, where are they? I have read a lot of Romanian history; I found only a few notes on our music. And then, what would the Romanian historian say about our beautiful Romanian musical art? We don’t know if our Conservatory has a department for music history. Of course it does. … Then what does the professor talk about when he discusses our music and composers? … Why don’t we have our own masters? We would be so proud!Footnote 77

Enescu, a Prophet in his Own Country?

What happens when such a composer finally arrives? The answer can only be given by analysing the reception of the first Romanian composer who obtained a truly resounding international success: George Enescu, who was only 17 years old when his symphonic suite Poème Roumain was first performed at the Châtelet Theatre in Paris, on 6 February 1898, during the Colonne Concerts (see Fig. 5). Initially reports of this event were enthusiastically and proudly spread to readers in Romania:

The success … was complete and the musical critics of the most important newspapers in Paris [Le Figaro, Le Journal, L’Eclair] unanimously recognize the value of this composition. … We fully congratulate our young compatriot asking him to continue, further along the path he opened, hoping he will do the same for our ignored folk music as Chopin, Sarasate, Moszkowski, Liszt or Brahms did for Polish, Spanish, Hungarian or Gypsy music.Footnote 78

Fig. 5 Enescu, at the age when he composed Poème Roumain

Due to its success in Paris, Poème Roumain was performed in Bucharest (see Fig. 6) to a sold-out crowd, and was conducted by Enescu himself in the presence of the king. But no man is a prophet in his own country, and Enescu was no exception. Critics, finally confronted with the ‘originality’ they had only dreamed of until then, could not go beyond their limitations. Suddenly, in the analysis of the work, their nationalist reflexes spring back to life, giving lessons about how a ‘Romanian poem’ should be and labelling all that conflicts with their own recipes as blatant mistakes; even the meaning of a concept such as ‘programmatic music’ seems to be foreign to them:

We declare, from the beginning that in the first part of the Poème Roumain there is nothing Romanian, except the Doina motifs at the end. … After a description of the landscape which we could hardly see [sic] in the music itself, bell chimes are heard – the author omits the characteristically Romanian toacă Footnote 79 – as well as distant choirs performing the evening service. … Most importantly, the author should have studied oriental music or at least our religious music.…

Mr Enescu’s principle motif is an obscene song from Bucharest, a trivial one at that, musically speaking, that doesn’t even have the merit of being a dancing aria. … He emphasizes it as if it were a true discovery … immediately passing onto the National anthem, whose solemnity made the entire audience stand up, along with the royal family. … He should have consulted the works of our very few masters, before fulfilling the idea of his poem – which is quite wrong in its conception – because he lacks knowledge and personal experience …. And regarding the motif, a Romană or a Bătută Footnote 80 would have created a more beautiful effect.Footnote 81 (See Fig. 7)

Fig. 6 The Romanian Athenaeum in Bucharest, where Enescu’s Poème Roumain received its Romanian premiere (post card)

Fig. 7 The score Bătută for piano, by Victoria Cosub-Zamfirescu (front cover).

In another review, the three performances of Poème Roumain are considered a great mistake:

It is understandable … the inexperienced composer could not understand that it wasn’t a good idea to perform the Poème three times in a row. However good and delicious champagne is, if it’s too much, the pleasure of the first glass will not be repeated. … For people that had already heard it twice, the composition became indifferent to them.Footnote 82

These texts reflect only the first impressions of Enescu’s music on his compatriots. The ascendant trajectory of its international successes in the next years brought him, in the spirit of the same romantic ideology – prolonged in Romania long after the end of the nineteenth century – more than his recognition: his evolution to mythological status as a national composer.

In the End, a Few Conclusions

Still in its incipient stages, late nineteenth-century Romanian music criticism reflects a rudimentary musicological thinking that is full of contradictions and awkwardness. Organically embedded in the political direction to which Romania was committed – as a young independent state seeing to shorten as swiftly as possible its distance from ‘the civilized world’, the West – the Romanian musical press adopted two starkly opposed approaches to the local musical scene, one apologetic, the other, derogatory. Although apparently irreconcilable, they were both fundamentally fed by the same inferiority complex, derived from the sense of belonging to a minority (musical) culture. Unfortunately, they both failed to accurately diagnose the state of Romanian music, and they proved inefficient in offering the public relevant viable benchmarks.

Discussion of any of the three genres – ‘folk’, ‘religious’ and ‘cultured’ – more often than not entailed a manipulative rhetoric, imbued with the clichés of a nationalism that was essentially romantic. The idealization of the ‘glorious’ history of the Romanian people and the evocation of the national ‘genius’ were, for example, ubiquitous in writing about Romanian music. However deftly employed, such propaganda could not make up for the authors’ lack of serious musical expertise or real criteria for aesthetic judgement. From this point on, an entire series of failures ensued, such as, for instance, the absence of any even remotely decent descriptions of the genres and styles of musical folklore, and the gratuitous caricaturing and defamation of Byzantine music, with no specifically musical aesthetic arguments. And finally, the case of Enescu’s Poème Roumain is symptomatic of the immaturity of contemporary Romanian critics – after such a long wait for an original piece, when it finally appeared and enjoyed success in both Paris and Bucharest, it was reproached precisely for breaking the mould.

Under these circumstances, it is difficult to say whether during the last decades of the nineteenth century the musical press had any influence whatsoever over the evolution of Romanian composition and interpretation. The most obvious answer seems to be a negative one: during this period there are musicians who manage to achieve European recognition, while the theoreticians of the phenomenon, stuck as they were in their anachronistic nationalist romantic thinking, remain utterly obscure. And still, one cannot but acknowledge the merit of these musical journalists who did create a certain level of expectation.

Unfortunately, Romanian musicology would long continue to be influenced by nationalism. It was aggressively promoted during the entire twentieth century as a weapon of the ideologies that marked the Romanian political and cultural climate – whether we’re talking about the fascism of the 1930s and 1940s or the post-war communism that lasted for over half a century. Inevitably, the Romanian musical press had no chance of escaping this systematic infection, whose consequences still haunt us to the present day.