The reputations of professional journals play a major role in the academy. Graduate students are encouraged to publish their research in top journals in order to maximize their chances of obtaining faculty positions (Wuffle Reference Wuffle1989). For faculty members, journal prestige influences merit reviews and promotion and tenure decisions, as well as a researcher’s overall reputation in the academy (Marshall and Rothgeb Reference Marshall and Rothgeb2011; Whicker, Kronenfeld, and Strickland Reference Whicker, Kronenfeld and Strickland1993). For teachers, a journal’s reputation can act as a proxy for the quality of the research published in it and thus influence whether articles from that journal are assigned in the classroom (Colgan Reference Colgan2016; Stoan Reference Stoan1984). Moreover, grant-making bodies weigh the quality of an applicant’s journal publications as part of their decision-making processes (McLean et al. 2009).

This article adds to our understanding of journal quality by reporting the results of a survey that captures how political scientists view peer-reviewed law journals in terms of overall impact, familiarity, article quality, and reading and submission preferences. In addition, it examines the extent to which the evaluation of journal quality differs depending on a researcher’s methodological approach. Taken as a whole, the findings reveal that scholars generally agree on a set of top peer-reviewed law journals, although some differences do exist based on the methodological approach of the respondent.

Investigating political scientists’ views of peer-reviewed law journals matters for a number of reasons. First, existing rankings of law journals overwhelmingly focus on citation patterns in student-edited law reviews (e.g., Cullen and Kalberg Reference Cullen and Kalberg1995; Doyle Reference Doyle2004; Shapiro Reference Shapiro2000; but see Eisenberg and Wells Reference Eisenberg and Wells2014). Though student-edited law reviews certainly contribute to our understanding of legal phenomena, the fact remains that, because they are not peer-reviewed, student-edited law reviews do not carry the same weight outside of law schools as peer-reviewed journals (e.g., Epstein and King Reference Epstein and King2002; Friedman Reference Friedman1998).Footnote 1 This may be a particular concern for junior faculty members, who might be discouraged from publishing in student-edited law reviews because they are not peer-reviewed (Zorn Reference Zorn2006).

Second, many peer-reviewed law journals are multidisciplinary and attract manuscripts from a wide range of fields, including anthropology, economics, history, law, political science, psychology, and sociology. This means that scholars from varied disciplines fight for space in the same journals and also implies that scholars from different disciplines might view the same journals differently, indicating the need for discipline-based journal rankings. Moreover, it highlights a problem with relying on impact factors based on citation counts to capture journal quality. For example, Law and Human Behavior is the highest ranked peer-reviewed law journal according to its Journal Citation Reports impact factor (Eisenberg and Wells Reference Eisenberg and Wells2014). Although it frames itself as a “multidisciplinary forum” (American Psychological Association 2016), it overwhelmingly publishes research by psychologists, who then frequently cite the journal (Shapiro Reference Shapiro2000). Thus, it is unlikely that political scientists, who seldom publish in the journal, would rank it nearly as highly as its Journal Citation Reports impact factor would suggest. As the survey results below indicate, political scientists, in fact, rank this the 49th overall peer-reviewed law journal. Thus, relying on citation count-based impact factors can be particularly troublesome in the context of multidisciplinary journals because a journal’s citation count-based impact factor may be driven almost entirely by a particular discipline that favors the journal.Footnote 2

Finally, I focus on peer-reviewed law journals since we lack information on how political scientists view the very large and expanding number of such journals.Footnote 3 To be clear, a small handful of these journals have appeared on reputational surveys of journals administered to political scientists (e.g., Garand and Giles Reference Garand and Giles2003; Giles and Garand Reference Giles and Garand2007; Giles and Wright Reference Giles and Wright1975). However, the vast majority of the 95 peer-reviewed law journals featured on the survey reported here do not appear on previous surveys. By providing a thorough examination of how political scientists view peer-reviewed law journals, my hope is that this article will aid scholars as they formulate their publication strategies and evaluate the scholarly work of their colleagues. Thus, this paper contributes to a growing literature that examines the reputations of journals operating within particular subfields (e.g., Arena Reference Arena2014; Doyle Reference Doyle2004; Eisenberg and Wells Reference Eisenberg and Wells2014; Maliniak, Peterson, and Tierney Reference Maliniak, Peterson and Tierney2012).

By providing a thorough examination of how political scientists view peer-reviewed law journals, my hope is that this article will aid scholars as they formulate their publication strategies and evaluate the scholarly work of their colleagues.

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

The strategy used to gather information on the reputational rankings of peer-reviewed law journals closely follows that developed in Garand and Giles (Reference Garand and Giles2003), with two notable exceptions. First, this survey was conducted online (see also Garand et al. Reference Garand, Giles, Blais and McLean2009; McLean et al. 2009), instead of via the mail. Second, only peer-reviewed law journals appeared on the survey, whereas Garand and Giles include a wide array of political science journals. The decision to focus only on peer-reviewed law journals was purposeful and driven by research on survey methodology; 95 journals appear on the survey, and including additional general political science journals would have effectively doubled the size of the survey as Garand and Giles included 115 political science journals on their survey. Including these additional journals would have likely decreased the response rate and increased the number of non-responses on several of the open-ended questions that appeared on the survey (e.g., Crawford, Couper, and Lamias Reference Crawford, Couper and Lamias2001; Rogelberg and Stanton Reference Rogelberg and Stanton2007).

The online survey was sent to all 480 members of the Law and Courts Section of the American Political Science Association (APSA) during the spring of 2016.Footnote 4 The set of respondents includes faculty and graduate students from PhD-granting institutions and faculty from non-PhD-granting institutions, as well as a small number of individuals employed conducting legal research outside of academia (e.g., for the federal government and think tanks).Footnote 5 The set of respondents includes both US and international scholars. After excluding responses from practicing lawyers without a connection to the academy from the survey results, 191 individuals returned full responses. The response rate was thus 40%, which compares favorably to the 28% overall response rate reported by Garand et al. (Reference Garand, Giles, Blais and McLean2009).

To determine which journals to include on the survey, a two-pronged strategy was employed. First, all peer-reviewed journals appearing in the “law” category on the Web of Science (formerly ISI) Journal Citation Reports were included (84 journals). Second, faculty from both liberal arts colleges and research-oriented universities in the Five College Consortium (Amherst College, Hampshire College, Mount Holyoke College, Smith College, and the University of Massachusetts Amherst) whose research focuses on legal issues were asked to contribute the names of peer-reviewed law journals that should be included on the list, resulting in the addition of 11 journals for a total of 95 journals. In addition, respondents were given space to rank up to 10 journals that did not appear on the list.

For the purposes of this survey, “peer-reviewed journals” are those that are evaluated by reviewers on an open, single-blind, or double-blind basis, as well as those refereed by a team of faculty editors (but not external reviewers). It does not include student-edited law reviews (e.g., McCormack Reference McCormack2009). It was straightforward to identify peer-reviewed journals, as they almost uniformly state on their webpages that they are “peer-reviewed” or “refereed” and explain the reviewing process.

The survey questions and design closely followed those developed by Garand and Giles (Reference Garand and Giles2003). Respondents were first asked to provide descriptive information about themselves, such as their country of origin, the highest degree offered at their institution, and their age, gender, and current academic rank. In addition, respondents were asked to identify the methodological approach that they most often employ and the regional focus of their research.

Following these descriptive questions, the survey queried respondents regarding their evaluations of peer-reviewed law journals in three ways. First, respondents were asked the following question (adopted from Garand and Giles Reference Garand and Giles2003):

Assume that you have just completed what you consider to be a very strong paper on a legal topic in your area of expertise. Indicate the first peer reviewed law journal to which you would submit such a manuscript. Assuming the paper is rejected at your first choice, please indicate the second and third journals to which you would submit the manuscript.

Next, respondents were presented with a list of 95 peer-reviewed law journals and were asked to identify the journals with which they are familiar. Respondents were informed that they would only be asked to rate journals with which they are familiar and were further informed that they will be able to add journals that the survey omitted that they feel should be included. Following this, respondents were asked to “assess each journal in terms of the general quality of the articles it publishes using a scale of 1 to 10,” where 1 is “poor,” 5 is “adequate,” and 10 is “outstanding.” Finally, respondents were asked the following question (adopted from Garand and Giles Reference Garand and Giles2003): “Which peer reviewed law journals do you read regularly or otherwise rely on for the best research in your area of expertise?” Respondents were allowed to list up to five journals.

To measure journal impact, I follow Garand and Giles (2003, 294–95) in recognizing that a journal’s impact is a function of both the extent to which scholars are familiar with a journal and the strength of the evaluations that scholars give to a journal. In other words, the strongest journals are those that a large number of scholars are familiar with and those that are held in high regard by scholars. Accordingly, I adopt the Garand and Giles (2003, 295) measure of journal impact, which is calculated as follows:

Journal evaluation captures the average assessment of each journal according to the quality of the articles it publishes, on a 1 to 10 scale. Journal familiarity is the proportion of respondents who indicated that they are familiar with each journal. This measure of impact has a theoretical range of 0 to 20, although the actual range in the data is 0 to 15.5. If no respondents are familiar with a journal (and thus no respondents rank that journal), it would score a 0. If every respondent indicated familiarity with a journal and also ranked that journal a 10, it would receive a 20. The journal impact measure is closely correlated with both journal familiarity (r = 0.86) and journal evaluation (r = 0.69), and gives fairly equal credit to these individual measures.Footnote 6

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

Table 1 reports the results pertaining to journal impact, journal evaluation, and journal familiarity, with the journals listed in order of their impact rank.Footnote 7 With two exceptions, the top ten journals are among the most widely recognized and highly evaluated peer-reviewed law journals. Consider the top three journals. Law & Society Review is one of the oldest peer-reviewed law journals, having published its first issues in 1966, and has published some truly seminal research, including Galanter (Reference Galanter1974) and Felstiner, Abel, and Sarat (Reference Felstiner, Abel and Sarat1981). Law & Social Inquiry is slightly newer, but still very well established, having first published in 1976 under the name American Bar Foundation Research Journal. Journal of Law and Courts is the new kid in town, having published its first issue in 2013. That it is less than five years old and is the second highest ranked journal clearly indicates that it quickly gained the respect of scholars, no doubt displacing older journals in the process.Footnote 8

Table 1 Political Scientists’ Evaluations of Peer-reviewed Law Journals, 2016

Note: Mean Impact Rating is a journal’s overall impact based on the following formula: Journal Impact = Journal Evaluation + (Journal Evaluation × Journal Familiarity). Mean Evaluation Rating (Journal Evaluation) is the average journal evaluation on a 1 to 10 scale where 1 = poor, 5 = adequate, and 10 = outstanding. Proportion Familiar (Journal Familiarity) is the proportion of respondents who are familiar with the journal.

Four of the remaining top ten journals—Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization (fourth), Journal of Empirical Legal Studies (fifth), Journal of Legal Studies (seventh), and Justice System Journal (ninth)—tend to publish research in the quantitative and/or formal traditions. The sixth highest ranked journal is the Annual Review of Law and Social Science, which publishes authoritative and critical review articles on a range of socio-legal subjects.

The two remaining journals in the top ten are interesting for different reasons. The European Journal of Migration and Law publishes law and policy research primarily devoted to European migration and is the only specialty journal—in the sense that it publishes research with a particular thematic focus—in the top ten. Only two respondents indicated familiarity with this journal (with a rank of 10 in terms of its quality) so its top ten ranking should be taken with a grain of salt. Judicature rounds out the top ten. This journal, published by the now defunct American Judicature Society from 1917 to 2013, functioned as a generalist journal that published relatively short articles targeted at both academics and legal professionals. Since 2014, it has been published by the Duke Law Center for Judicial Studies; it appears that its current primary audience is judges as it is currently described as “The Scholarly Journal for Judges” (Duke Law Center for Judicial Studies 2016). Unlike the European Journal of Migration and Law, which is little known, but highly ranked by those familiar with it, Judicature is very well known, but not evaluated highly in terms of the articles it publishes.

The second grouping of journals (11-20) primarily contains generalist law journals that publish on a range of topics, although some more specialized journals also appear. Among the generalist journals, some publish work from a wide range of disciplines (e.g., Law & Policy, Law, Culture and the Humanities), while others are more closely associated with a particular disciplinary perspective (e.g., Law & History Review, Journal of Law and Economics). Of the specialty journals, some are international in scope, but focused on a particular topic area (e.g., International Journal of Constitutional Law), and others are clearly associated with a particular discipline, such as Criminology.

Similar to what Garand and Giles (Reference Garand and Giles2003) find with respect to political science journals in general, the third tier of law journals consists primarily of journals “that are either reasonably well regarded or reasonably well known, but not both.” For example, the American Law and Economics Review is reasonably well known, ranking fifteenth overall in terms of familiarity, but is not highly evaluated in terms of its quality (43rd overall). Conversely, the International Review of the Red Cross is not well known (57th overall), but is highly regarded by those familiar with it (fifth overall).

Finally, the 48% of journals below the 39th impact ranking are neither widely recognized nor highly regarded. Indeed, all of the journals fall below the mean (6.76) in terms of journal evaluation and well below the mean (0.13) in terms of familiarity, with one exception. Jurimetrics, published by the American Bar Association Section of Science and Technology Law, is reasonably well known (17th overall), but not highly regarded (68th overall).Footnote 9

Evaluating Journal Quality

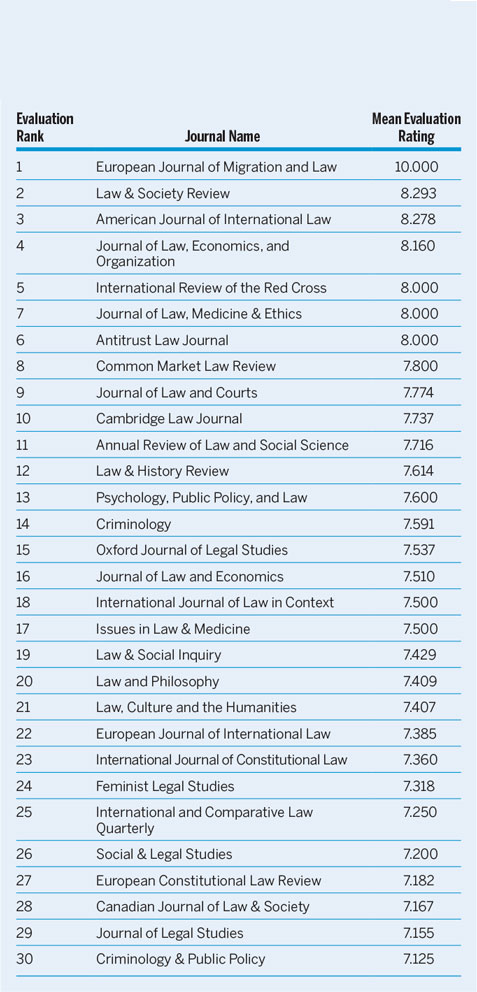

In an effort to take a closer look at political scientists’ evaluations of the quality of articles published in peer-reviewed law journals, table 2 reports the top 30 journals in terms of the average evaluation rating on a 1 to 10 scale. Of these 30 journals, only seven appear in the top 10 according to journal impact in table 1: European Journal of Migration and Law; Law & Society Review; Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization; Journal of Law and Courts; Annual Review of Law and Social Science; Law & Social Inquiry, and Journal of Legal Studies. With the exception of the European Journal of Migration and Law, which is not well known, these are the journals that are the most highly respected and well known among political scientists.

Table 2 The Top 30 Ranked Peer-reviewed Law Journals in Terms of Article Quality, 2016

The remaining journals on the list provide evidence of specialization among political scientists studying law. In particular, there is an assortment of journals that are not well known to most political scientists, but that are very highly ranked by those familiar with the journal, most notably European Journal of Migration and Law, American Journal of International Law, International Review of the Red Cross, and Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethnics. All of these are specialty journals that publish research regarding a particular thematic focus and are apparently very well regarded by scholars working in those thematic areas.

Evaluating Journal Familiarity

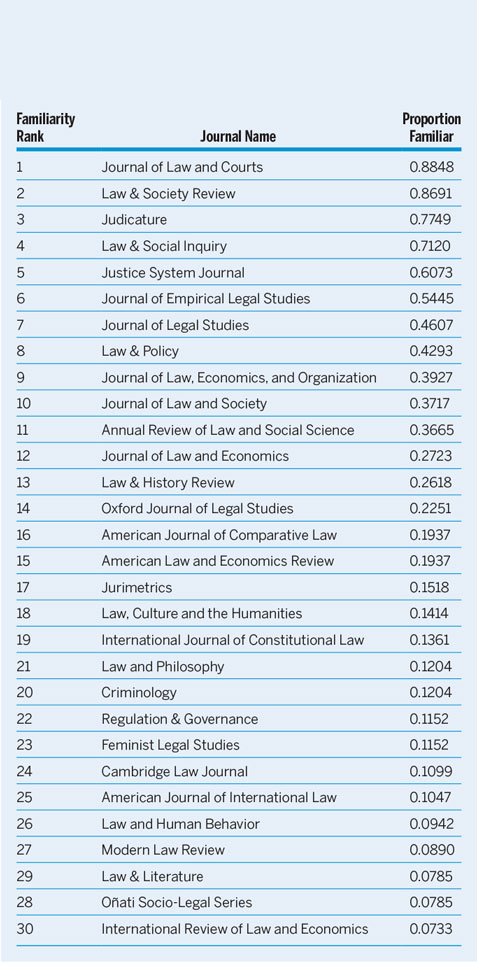

Table 3 examines how political scientists view peer-reviewed law journals by reporting the top 30 journals according to the proportion of respondents who indicated familiarity with a journal. This table reveals that there are only six peer-reviewed law journals that a majority of respondents indicate familiarity with, which is identical to what Garand and Giles (2003, 299) find with respect to political science journals. Journal of Law and Courts and Law & Society Review are the most recognized journals, with more than 85% of respondents indicating familiarity with these journals. Judicature and Law & Social Inquiry come next, both of which are recognized by more than 70% of respondents. Following this, there is a drop-off, with 61% of respondents indicating familiarity with Justice System Journal and 55% indicating familiarity with Journal of Empirical Legal Studies.

Table 3 The Top 30 Ranked Peer-reviewed Law Journals in Terms of Familiarity, 2016

The next group of journals, recognized by approximately 25% to 50% of all survey respondents, consist primarily of generalist law journals, such as Law & Policy, Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, and Law & History Review, although a few of these journals are associated with particular disciplinary or methodological approaches. Less than 25% of respondents indicated familiarity with journals ranked below 13th. These journals constitute a mix of generalist journals (e.g., Law, Culture, and the Humanities), specialist journals (e.g., American Journal of Comparative Law), and journals connected to particular disciplines (e.g., Law and Human Behavior, which is the official journal of the American Psychology-Law Society of the American Psychological Association).

Evaluating Preferred Journal Submissions

In addition to the impact, quality, and familiarity measures, journals can also be evaluated based on respondent preferences for the submission of their own high-quality work (Garand and Giles Reference Garand and Giles2003). To do this, respondents were asked to indicate and rank the top three peer-reviewed law journals to which they would send a “very strong paper on a legal topic in your area of expertise.” These results appear in table 4. The entries indicate the number of survey respondents who ranked each journal as the first, second, and third peer-reviewed law journal to which they would submit a very strong paper, and the total column contains the total number of times the journal was recognized. I have included only journals that received more than 15 overall mentions (see Garand and Giles Reference Garand and Giles2003).

Table 4 Respondent Preferences for the Submission of High Quality Manuscripts to Peer-reviewed Law Journals

Note: Entries are the number of respondents who selected each journal as the first, second, or third peer-reviewed law journal to which they would submit “a very strong paper on a legal topic in [their] area of expertise.”

Two journals clearly stand out in table 4: Law & Society Review and Journal of Law & Courts. Law & Society Review is clearly the top journal for high-quality submissions, receiving twice as many first-place selections than the runner up, Journal of Law and Courts, and the most total selections overall. This table also provides additional evidence for the very high esteem to which Journal of Law and Courts is held as it garnered the second most first-place selections and the most second-place selections. Moreover, both of these journals received more than twice as many overall selections than any other journal appearing in table 4.

Following these journals, Law & Social Inquiry has the third most overall mentions (41), and the second most second-place recognitions among the journals. The remaining journals have between 17 and 31 overall mentions. Three of these journals are generalist law journals that appeared on the top 10 highest ranked journals according to their impact factor in table 1: Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, and Journal of Legal Studies. Two of these journals, American Political Science Review and American Journal of Political Science, did not appear on the list in table 1 as they are generalist political science journals, as opposed to law journals. This indicates that legal scholars recognize these journals as among the most prestigious in the field and corroborates the findings of Garand and Giles (Reference Garand and Giles2003), which ranked American Political Science Review and American Journal of Political Science the first and third overall journals, respectively, in terms of preferences for high-quality submissions (see also Martinek Reference Martinek2011).Footnote 10

Evaluating Preferred Reading Sources

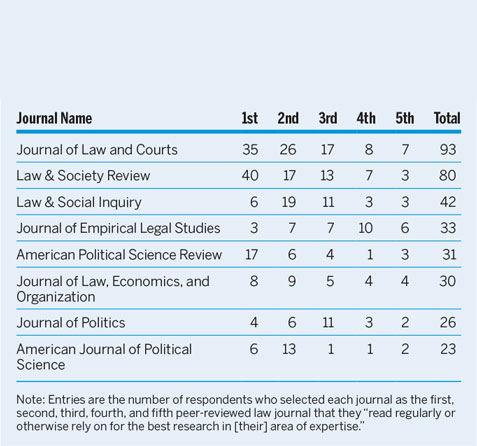

The final manner in which journals are evaluated appears in table 5. This provides information on respondents’ preferences for journals based on those they read regularly or otherwise rely on for the best research in their area of expertise. Respondents were asked to name up to five journals each. The entries indicate the number of respondents who ranked each journal first through fifth, as well as the total number of mentions of each journal. I include only journals that received more than 20 overall mentions by respondents.

Table 5 Respondent Preferences for Reading Peer-reviewed Law Journals

Note: Entries are the number of respondents who selected each journal as the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth peer-reviewed law journal that they “read regularly or otherwise rely on for the best research in [their] area of expertise.”

As with table 4, two journals stand out: Law & Society Review and Journal of Law and Courts. Law & Society Review has the most first-place mentions, while Journal of Law and Courts has the most second-place mentions and the most mentions overall. Both of these journals have almost twice as many overall recognitions as Law & Social Inquiry, the third highest ranked journal according to overall mentions and the second highest ranked journal according to second-place mentions.

Two other peer-reviewed law journals also appear in table 5. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies has the fourth highest number of overall mentions and the most fourth-place mentions. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization has the sixth highest number of overall recognitions. The three remaining journals, American Political Science Review, Journal of Politics, and American Journal of Political Science, are all highly regarded generalist political science journals. For example, these are the top ranked political science journals in terms of preferences for journal reading according to Garand and Giles (Reference Garand and Giles2003). Thus, there is a good deal of overlap in terms of how general political science journals are viewed among political scientists conducting legal research and those outside of this subfield.

Exploring Methodological Differences

To this point, peer-reviewed law journals have been evaluated according to the views of survey respondents, providing a great deal of information as to how these journals are evaluated generally. But, there is reason to believe that scholars who employ different methodological perspectives might evaluate journals differently (Garand and Giles Reference Garand and Giles2003). As noted above, several of the journals that appear in the top 10 list according to impact factor tend to publish primarily quantitative research (e.g., Journal of Empirical Legal Studies). Thus, such journals might be less favorably viewed by those who employ qualitative methods. Conversely, some of the journals on this top 10 list, such as Law & Social Inquiry and Law, Culture and the Humanities, primarily publish qualitative research. Still others, such as Law & Society Review and Journal of Law and Courts, publish research from a variety of methodological approaches.Footnote 11

Table 6 provides a look at the average journal quality scores broken down by respondents who identified themselves as doing primarily quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods research.Footnote 12 This table includes the top 20 journals according to journal impact factor as reported in table 1. Recall that journal quality is on a 1–10 scale, where 1 is “poor,” 5 is “adequate,” and 10 is “outstanding.” The mean for journal quality is 6.76 (standard deviation = 0.942). The F-test indicates whether the differences between the group means are statistically significant at p < 0.01.

Table 6 Political Scientists’ Evaluations of Peer-reviewed Law Journals in Terms of Article Quality by Methodological Approach, 2016

Note: *p < 0.001. Entries represent the average journal evaluation on a 1 to 10 scale where 1 = poor, 5 = adequate, and 10 = outstanding. European Journal of Migration and Law was not rated by any quantitative or qualitative scholars and thus there is no way to compare the average ratings across the groups.

Two notable findings emerge from this table. First, there is a good deal of consistency across the groups of scholars who associate themselves with the three methodological approaches. Indeed, there are no statistically significant differences across the three groups with respect to 14 of the 20 peer-reviewed law journals reported in table 6.Footnote 13

Second, quantitative scholars rank all five journals in which statistically significant differences emerge lower than do qualitative and mixed-methods scholars. For example, quantitative researchers rank Law & Society Review about a standard deviation below qualitative and mixed-methods scholars. However, they still rank it about a standard deviation above the overall mean for journals. The biggest differences among the groups involve Law, Culture and the Humanities and Law & Social Inquiry, both of which quantitative scholars rank below the overall mean. Quantitative scholars rank Law, Culture and the Humanities more than three standard deviations below qualitative scholars and they rank Law & Social Inquiry almost three standard deviations below qualitative scholars. As noted above, these journals publish primarily qualitative work, which likely accounts for the wide variation between quantitative and qualitative scholars.

CONCLUSIONS

This article provides the first systematic evaluation of how political scientists evaluate peer-reviewed law journals for the purpose of assisting scholars as they develop their publication strategies and evaluate the work of other researchers. To do this, political scientists were surveyed on their opinions regarding 95 peer-reviewed law journals. Following Garand and Giles (Reference Garand and Giles2003), journals were evaluated on the basis of five measures: overall impact, familiarity, article quality, submission preferences, and reading preferences. In addition to examining the overall evaluations of journals, special attention was devoted to exploring how journal evaluations might differ depending on researchers’ methodological approaches.

Considering journal rankings across all of the measures employed here, two journals stand out as especially strong: Law & Society Review and Journal of Law and Courts. These are the top ranked peer-reviewed law journals in terms of overall impact, familiarity, reading preferences, and submission preferences. In addition, they are both ranked in the top 10 according to article quality. Following these journals, Law & Social Inquiry, Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, and Journal of Empirical Legal Studies are also very highly ranked across measures, rounding out the top five for overall impact and appearing in the top 10 in terms of familiarity, reading preferences, and submission preferences. Thus, these appear to be the overall top five peer-reviewed law journals in 2016 according to political scientists. However, this study also reveals the existence of differences in journal rankings depending on researchers’ methodological approaches. In particular, quantitative scholars ranked Law & Society Review and Law & Social Inquiry lower than did qualitative and mixed-methods scholars. This suggests that political scientists evaluate journal quality in part based on the extent to which they believe their preferred methodological approaches appear in those journals.

Taken as a whole, this article has provided a great deal of information regarding how political scientists evaluate peer-reviewed law journals. Future studies may choose to expand on these findings in a number of ways. For example, this study was based entirely on survey results. Though this is the dominant approach for evaluating journals in the discipline (Garand and Giles Reference Garand and Giles2003), citations represent another way that journals can be evaluated (e.g., Giles and Garand Reference Giles and Garand2007; Jacobs Reference Jacobs2016). In addition, it will be valuable to include a small number of general political science journals on future surveys for the purpose of establishing how peer-reviewed law journals compare to journals such as the American Political Science Review, American Journal of Political Science, and Journal of Politics in the eyes of survey respondents. Finally, it will be useful to expand this research to include scholars outside of political science. As noted above, because most peer-reviewed law journals frame themselves as publishing work from a variety of disciplinary perspectives, it will be important to investigate how scholars from different disciplines evaluate the same set of journals.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096517002529

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am extremely grateful to Diana Alsabe for outstanding research assistance, Micheal Giles for providing advice and sharing survey materials, Wendy Martinek for insightful comments on an earlier version of this article, Brian Schaffner for guidance in designing the online survey employed here, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions. I am also thankful to participants in the Five College Legal Studies Seminar and the University of Massachusetts Amherst American Politics working group for their very useful feedback. Naturally, I take full responsibility for any errors in fact and/or judgment. In the interest of disclosure, I was a member of the editorial boards of Justice System Journal, Law & Society Review, and Political Research Quarterly when this research was conducted.