1. Introduction

The Catalan economy expanded exponentially from 1740, establishing a complex system of exchanges that mainly covered the Spanish market, certain European countries – from the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean –, and the Spanish colonies of America. It was based on the expansion of viticulture and the manufacture of spirits, the production of calicoes, the stamping of imported raw canvas, the weaving of wool and silk fabrics and also the production of other manufactured goods, such as paper and books.Footnote 1 However, from the late 1780s, there was a series of economic crises that lasted until the 1830s. Together, these crises constituted the crisis of the Old Regime in Spain – with serious political and fiscal problems – that ran parallel to and, as this article will show, impacted upon the birth of Catalan industrialisation.

Some crises were of a temporary or conjunctural nature and others came from deeper causes. First, there was a crisis in the colonial market due to overproduction (1787), which had a serious effect on the manufacture of calicoes and may have also had an impact on the silk industry.Footnote 2 Others followed, arising from the wars against France (1793–1795) and England (1796–1801 and 1805–1808). The two last of these seriously harmed Spanish and Catalan colonial trade.Footnote 3 Almost simultaneously, the bad harvests at the end of the eighteenth century (1794–1795, 1797–1798, 1801–1802, 1803–1804 and 1804–1805) contracted the Iberian market. Of the crises which occurred between 1793 and 1808, that of 1797 was especially serious. It almost completely interrupted the exchanges with the American colonies, affecting the supply of American cotton, while internal demand shrank as a result of the war and of the bad harvests. Furthermore, in 1801, the Spanish crown again authorised exports of raw silk, which greatly increased the production cost of textiles using this fibre.Footnote 4 In addition, at the close of the eighteenth century, the English, Americans, Germans and Portuguese began to consolidate their presence in the Spanish colonial market,Footnote 5 disseminating the new fashions established in France and England, which weakened Catalan production. As if that were not bad enough, from 1808 to 1814 the Napoleonic army invaded Spain. During the war, Barcelona was occupied by the French army – giving rise to substantial emigration of the population – and the city of Manresa (also a focus of this article) was partially destroyed. This war represented an almost complete stoppage of activity. The European post-Napoleonic crisis then arrived. Finally, from 1810, pro-independence movements emerged in the colonies. By 1823, all the colonies on the American continent had been lost. In view of all of the above, the colonial market, very important for textile production in the two most important textile production sites in Catalonia in Barcelona and Manresa, was practically non-existent from the beginning of the nineteenth century, and the Spanish market was considerably weakened.Footnote 6 The long crisis only began to recede when the Spanish internal market began to be organised, above all starting from the protectionist measures which were decreed in 1820 on Castilian grain and Catalan textiles.Footnote 7 After all these problems, a new commercial system was built in Catalonia, which took hold in 1830–1840.Footnote 8

Not all these crises have been studied from the same angle or in the same detail. They have been partially studied, answering questions basically of an economic and business nature.Footnote 9 Studies have focused on the following: the economic consequences of the colonial 1790–1808 commercial crisis,Footnote 10 the challenges that affected the dynamic development of calicoes and painted canvases between 1740 and 1833 and how they were overcome,Footnote 11 the economic impact of the 1808–1814 Napoleonic war and of the loss of the colonial market,Footnote 12 the transformation of wool manufacturing,Footnote 13 the changes in the Atlantic export–import relationship,Footnote 14 and the importance of the demographic crisis.Footnote 15 Thanks to these studies, we have a good overview of what occurred in the production of printed cotton textiles in Barcelona in economic and technical terms. We know far less about the gendered impact of the crises, apart from Marta Vicente's research into the calico industry in Barcelona.Footnote 16 This present article investigates gender as far as the limited evidence allows, but the main objective of this study is to explain how the silk industry of Barcelona and Manresa – the two main Catalan silk manufacturing centres in the eighteenth century – managed to survive the long economic crisis described above.Footnote 17 The two cities had different structures of production and business and specialised in different kinds of silk products of different quality. In both cities, there was a silk weavers’ guild (gremi de velers or de teixidors de seda in Catalan), which was not completely abolished until 1836, together with all the other guilds. Nevertheless, the existence of this institution was not an obstacle for the industrialisation of both cities.

It is not easy to explain the consequences of the numerous crises that affected silk textile production in Barcelona and Manresa in the years indicated, given the situation of chaos and turmoil that was experienced during episodes of war (including the French invasion) and given the uncertainty of the period, since various changes were being introduced into technology and into the organisation of labour in textile manufacturing, basically in cotton production with the expansion of calicoes and the introduction and dissemination of three cotton spinning systems (the new machines patented originally by Hargreaves, Arkwright and Crompton). There were deaths of entrepreneurs, the closing of workshops and bankruptcies. Moreover, the sources which would allow us to analyse certain aspects of the crisis such as, for example, its impact on the organisation of labour and participation by workers of different ages and gender, are practically non-existent.

This article is organised in three main sections. The first describes the characteristics of the production of silk textiles in Barcelona and Manresa in the eighteenth century, while the second section looks at the channels used to overcome the crisis in silk weaving in Barcelona and Manresa in the nineteenth century. A third section provides some brief discussion of the roles played by women in these processes of adaptation, though, as already acknowledged, the evidence here is very limited. This will be followed by the conclusions.

2. The characteristics of the production of silk textiles in Barcelona and Manresa in the eighteenth century

In the eighteenth century, silk manufacturing already had a long tradition in the Iberian Peninsula, based on the Muslim legacy and the introduction of new technology and new types of textiles by Genoese artisans, above all in Valencia, at the end of the fifteenth century. Over the centuries, some silk centres declined while others flourished. Thus, Toledo declined in the eighteenth century, while Valencia came to dominate the industry and Catalonia emerged as a centre of production. The region of Valencia was the biggest producer of silk thread, and its capital was the main silk centre of the Spanish monarchy. The city basically produced luxury textiles and, at the time of its greatest splendour (the 1760s), it had between 3,500 and 3,800 looms.Footnote 18

In the mid-eighteenth century in Catalonia, silk textiles were made in seven towns, the only ones that the royal administration authorised to import silk, a raw material with a deficit in the region. Unlike the silk industry of Valencia, the Catalan sector specialised in the production of simple textiles, such as handkerchiefs and taffeta, in addition to weaving stockings and various types of ribbons which were easy to produce and had a low cost and high demand,Footnote 19 as dictated by fashion and the dissemination of consumer culture. The artisans of the silk sector were aware that this was where their competitive advantage lay.

The production of silk textiles in Barcelona – a city with 33,000 inhabitants at the beginning of the century and 90,000 at the end – experienced a clear expansion based on the preparation of these pieces and handkerchiefs with high demand.Footnote 20 The silk weavers’ guild, established in 1533, amended its ordinances in 1736,Footnote 21 when cotton textiles began to change consumer habits and the first calico factories were created in the city, an activity which became very important.Footnote 22 These new ordinances, in addition to establishing in great detail the goods which could be manufactured – and which other fibres could be used, in addition to silk –, regulated who could weave these articles, limited the hiring of apprentices to just one, forbade officials from setting up on their own behalf, forbade masters from working for people from outside the guild and prevented anyone who was not a master from operating a loom.Footnote 23 All women, except for the widows of masters, were excluded (by omission) from this trade guild.

The guild tried to reserve the right to weave the pieces to print the calicoes, but this clashed with broad opposition and could not be imposed. This silk-making sector expanded at the same time as other types of silk production, such as the weaving of stockings and of ribbons, which were under the regulations of a separate guild, the weaving of lace, which was unregulated, and the manufacture of calicoes. This expansion was part of an intense commercial activity closely linked to the port, from which not only textile products were shipped. The silk weaving masters of Barcelona did not, however, achieve the freedom to manufacture light silk textiles, which those from Manresa did obtain in 1772.Footnote 24 This imposed stagnation obliged the Barcelona silk weavers to weave products in accordance with the provisions of the 1736 ordinances.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, in Manresa – a town of some 7,000 inhabitants at the beginning of the century and 13,500 at the end – silk and its preparation were unknown and the most important industry was tanning, which formed the basis of the wealth of some families. It was not external traders who bought and marketed the tanned leather, but rather the tanners themselves who, without ever abandoning the production process, became merchants.Footnote 25 This productive and economic culture was continued by the silk weavers. The growth in the silk activity and in the guild was spectacular in the eighteenth century, to the extent that silk production became the main activity. In 1749, ordinances similar to those of Barcelona were enacted,Footnote 26 but the guild of Manresa, having obtained a privilege of free manufacture in 1772, had a more flexible organisational and productive structure than that of Barcelona, allowing it to adapt to new market demands. Some of this production – basically of handkerchiefs – did not meet guild standards and thus in theory could only be sold to the colonial and foreign markets, although there is evidence of illegal sales in Spanish territory.Footnote 27

The number of looms, masters or workshops existing in these two cities varies from one source of information to another. In Barcelona, the data on the number of masters (or workshops) are not at all reliable, because the guild concealed the true figure to evade taxation.Footnote 28 According to the tax payers’ register of the silk guild, officially there were 86 master silk weavers in 1729 and 93 in 1801, but another guild register, the ‘Llibre del misteri de la Sta. Espina del gremi de velers’, from 1764, cites more than 200 members.Footnote 29 In Manresa, in 1788 – certainly one of the moments of greatest expansion –, there were 509 silk weavers.Footnote 30 In both cities, the silk industry was completed with the production of different types of ribbons, braid and stockings (the latter, only in Barcelona). These activities also gave work to winders and dyers. All of the silk workers in Manresa together represented 56.2 per cent of all artisans.Footnote 31 At the end of the century, its economy revolved around silk, while that of Barcelona had a much more diversified production.

The dynamism in the production of silk textiles is expressed in the number of new admissions to the guild of silk weavers. Between 1782 and 1799, in Barcelona, 547 apprentices signed their contract before a notary (30.4 per year) and 440 master's agreements were granted between 1770 and 1808 (11.3 per year). In Manresa, over these 17 years, 263 apprenticeship charters were signed (14.6 per year) and 1,047 masters’ charters were recorded (an average of 26.8 per year).Footnote 32 Note that while the apprenticeship charters were more numerous in Barcelona, in Manresa there were more master's agreements, which indicates that the structure of the workshops was different. In Manresa, there were more workshops of masters hiring fewer apprentices or with their sons working alongside them instead.

Women participated in the production of silk textiles under the guild's restrictions. They did so differently depending on whether or not they belonged to families of masters – for families of journeymen the situation is less clear – from the silk weavers’ guilds of Barcelona and Manresa. The wives and daughters of masters participated in many ways in the running of the family workshop and many others worked as spinners and rodeteras who made balls or buns, or made silk skeins, working for the silk winders and the dyers. Only a few women worked on the silk looms because the majority of the silk fabrics which were made in Barcelona and Manresa in the eighteenth century were light and for this reason were made on simple looms. Few women worked moving the cords tied to the weaving reeds in complex looms as described for the tireuses de cordes in Lyons, by Anne Montenach in another article in this special issue. Outside the Barcelona and Manresa silk weavers’ guilds, some women, known as filempueres and tafetaneres independently wove different silk articles that they sold directly to consumers, sometimes earning a great deal of money and employing masters who were members of guilds. In 1636, they faced opposition from the Barcelona guilds of silk weavers and ribbon makers, but the Barcelona city council decided in favour of the women.Footnote 33 In Manresa, it seems to be the case that women could freely make cords – or a certain type of cord – as can be gathered from a lawsuit in 1770.Footnote 34 Furthermore, according to a 1788 text, women made ‘ribbons and cords’, while another text from 1797 reported that there were ‘more than 400 looms of hiladillo (coarse silk thread) and cotton ribbon which were vulgarly called vetes ( … ) Women also worked on these’.Footnote 35 Unfortunately, we do not know whether they did so independently or as wage earners.

The wives of the silk weavers, like those in other regulated trades, brought tangible and intangible capital to the family business on marriage, whether that run by their father-in-law or that created by the new spouses. They were fundamental to the smooth operation of workshops, as recognised by some testimonies of silk artisans and their families.Footnote 36 In 1779, the government authorised the work of women in all trades, including those monopolised by the guilds, although this did not modify the existing structures of production in the silk industry.

In the mid-eighteenth century, the silk weaving of Barcelona and Manresa had a complex productive structure based on small family workshops. However, various circumstances favoured the appearance of masters who, in addition to working in their own workshops, entrusted others to weave a specific number and type of pieces which they then marketed. In Barcelona, there was a fairly small guild elite which, at most, controlled an average of 15 looms per master and intervened in all types of business, although it does not appear that they were partners in big manufacturing or commercial companies.Footnote 37 In Manresa, at least from the end of the 1740s, modest and big family companies of silk weavers and silk ribbon or haberdashery artisans were created, with the participation of brothers-in-law and the contribution of the dowries of wives.Footnote 38 These companies moreover attracted capital investment from other silk weavers, institutions, or individuals who were remunerated at a rate of 6 per cent.Footnote 39 The initial capital was invested in working capital through a system of purchase and sale on credit, a mechanism which explains the spectacular growth of some companies but also their structural weakness, since any crisis could bankrupt the system, as occurred at the end of the eighteenth century.Footnote 40 Some of these Manresa silk companies were also devoted to marketing all kinds of goods. Several of them accumulated a huge capital. Pablo Miralda & C° was certainly the one with the most; it not only negotiated in silk textiles but also with various other products and imported others from the colonies.Footnote 41 The silk weavers of Barcelona do not appear to have developed this commercial strategy at the same level as the Manresa companies of silk weavers (and other silk makers).

Although the internal market was not negligibleFootnote 42 and some handkerchiefs were sold in Marseille, Amsterdam and Dunkerque,Footnote 43 in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, the most important market was the colonial market, at least for Manresa. Between 1777 and 1785, licences were granted to export 236,100 dozen handkerchiefs from Manresa to the Spanish colonies in America, 76.7 per cent of which were ‘produced’ by three companies from this city.Footnote 44 The colonial market – and to a lesser extent the internal market – was fundamental to the silk industry, and this dependency was, in turn, the weakness of the sector.

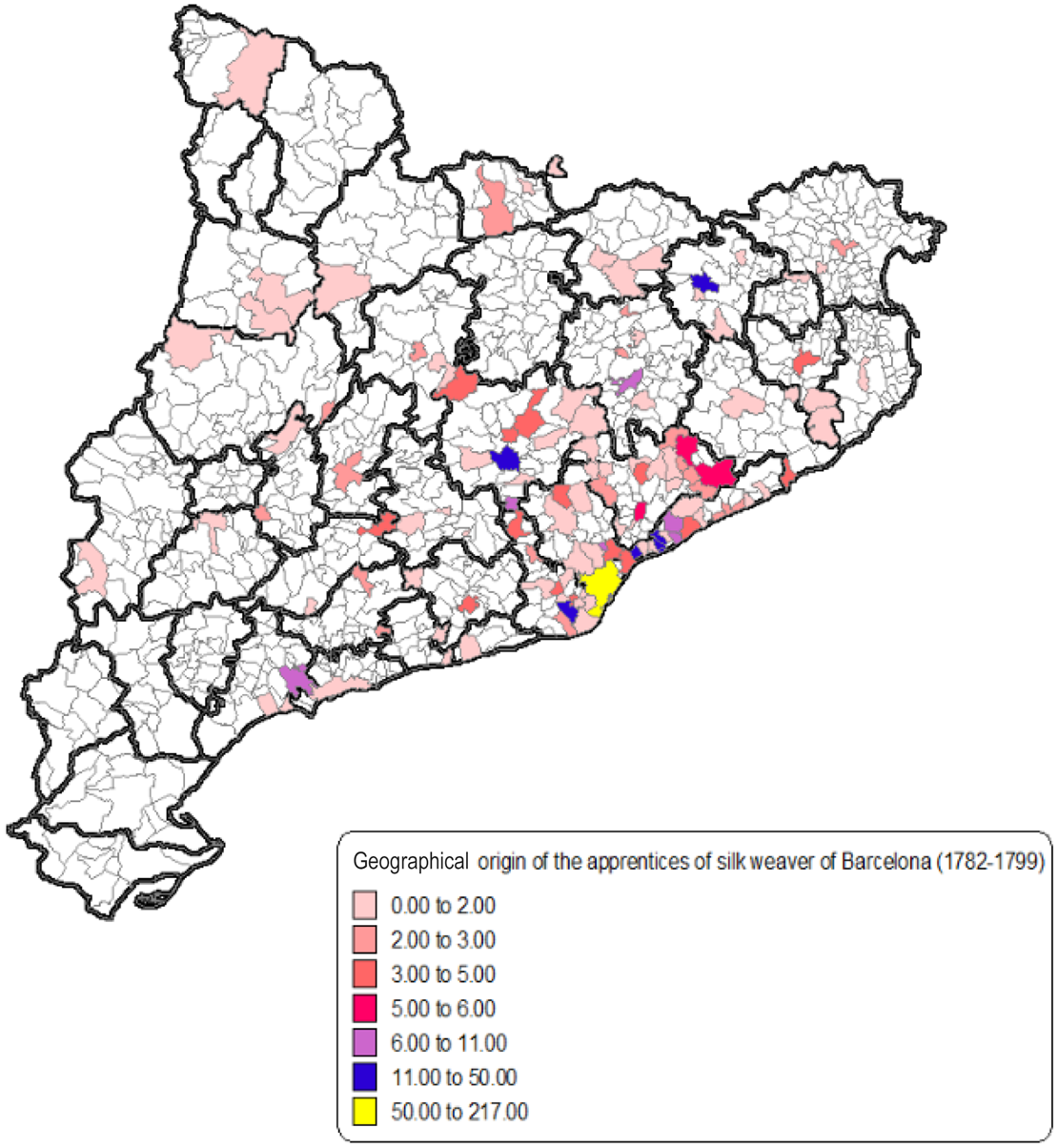

In silk weaving, each city featured its own distinct labour market, in part fed by immigration. In the years 1782–1799, that of Barcelona was very open, the majority of the apprentices being immigrants. 63.8 per cent came from outside the city, from all across the region (see Table 1 and Figure 1).Footnote 45 In Manresa, during the years 1760–1797, 40.9 per cent of these young people came from a dense group of municipalities around the city (see Table 1 and Figure 3).

Figure 1. Geographical origin of the apprentices of silk weavers of Barcelona (1782–1799).

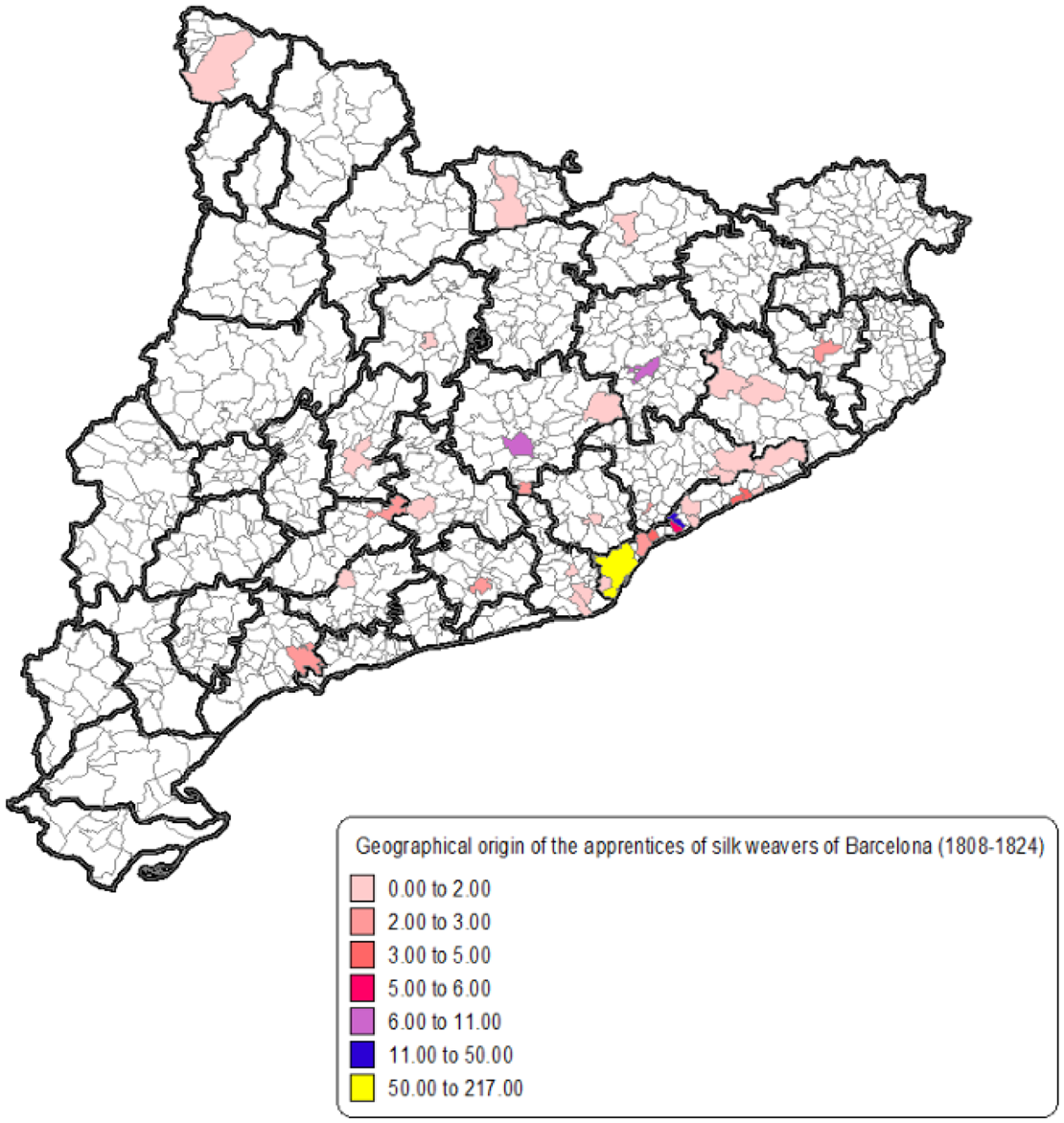

Figure 2. Geographical origin of the apprentices of silk weavers of Barcelona (1808–1824).

Figure 3. Geographical origin of the apprentices of silk weavers of Manresa (1760–1797) (Sample 1/3).

Table 1. Geographical origin of the apprentices of silk weavers in Barcelona and Manresa

Source: see note 32.

In short, the development of silk weaving in Barcelona and in Manresa in the eighteenth century gave rise to a complex productive, commercial and social structure. At the end of the century, there were in both cities some rich masters who traded in all kinds of products; several companies of silk weavers that had large capital, but only in Manresa; independent workshops which formed part of a network of companies, in which the masters participated through investments of capital repaid with interest; independent workshops engaged in both production and marketing in various ways and finally workshops with established ties of dependency to third parties who provided them with the silk and indicated which goods they had to weave. This productive structure was based on the work of masters, officials, apprentices and women whose livelihoods depended on the smooth running of the entire economic fabric. When the long economic crisis arrived, they had to confront it and adapt to the new situation.

3. The consequences of the crisis for the silk weavers of Barcelona and Manresa and their responses

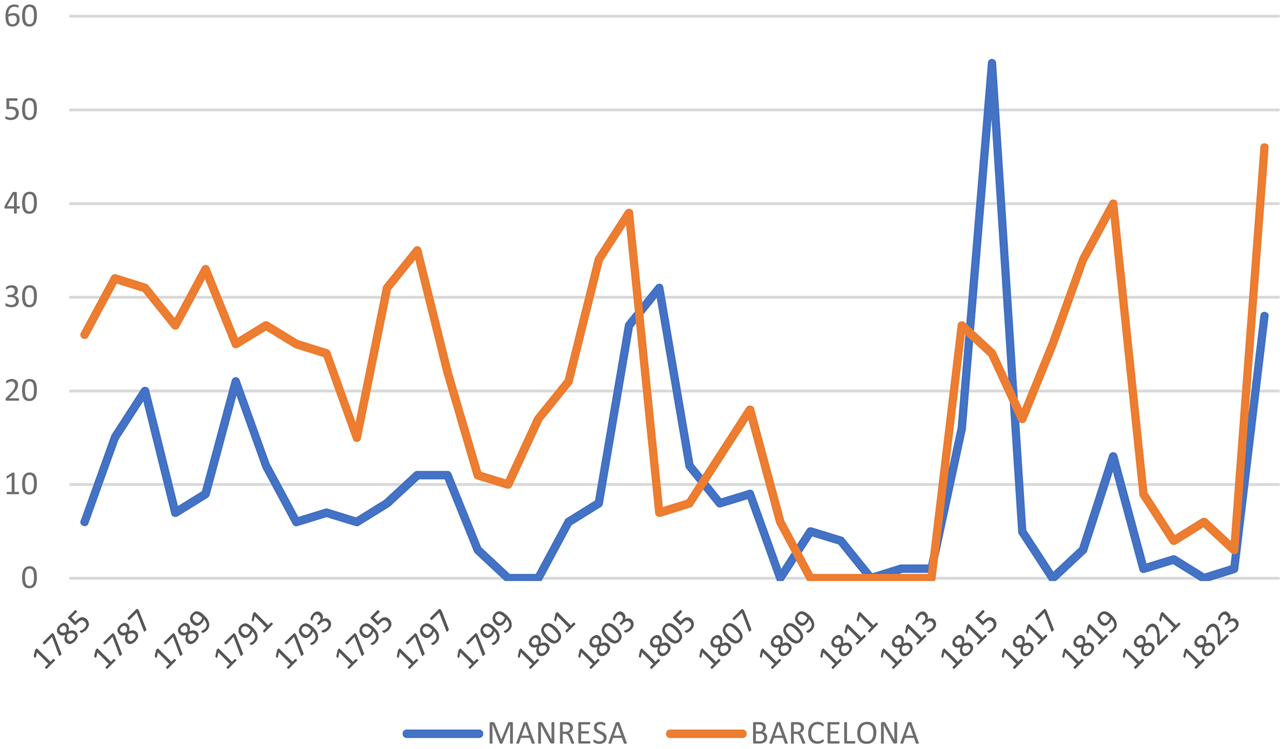

Under the difficult economic circumstances we have mentioned, the crisis was felt immediately in Catalonia.Footnote 46 In the absence of other specific data on its impact, the annual number of apprenticeships and the geographic origin of the apprentices are used as a reasonable indicator of the evolution of the silk sector in Barcelona and Manresa (Figure 5).

The fall in the number of apprenticeships (Figure 5) in these two cities from the years prior to the crisis of the 1790s until the period from 1805 to 1808 is clear, although there was an upturn in 1796, a year of relative normality in the midst of poor harvests, and between 1802 and 1804 thanks to the Treaty of Amiens with Great Britain, which began a short boom period when exchanges with the Spanish colonies recovered. Apprenticeship contracts practically disappeared during the Napoleonic war, especially in Barcelona, which was occupied by the French army throughout the conflict and where all guild activity was forbidden, but also in Manresa, where there were only eleven new apprenticeships in the six years of French invasion and war, although the town was not occupied permanently. The number of apprenticeship contracts did not recover until after the Napoleonic war. In Barcelona, recovery was more gradual over several years, while in Manresa, there was a much sharper peak in the number of apprenticeships, concentrated in the years 1814–1815.

It is interesting to highlight that the number of immigrant apprentices went down in both cities. Thus, in Barcelona, immigrants went from representing 79.3 per cent of apprentices in the five-year period between 1790 and 1794 to 54.1 per cent in the subsequent five-year period.Footnote 47 In the case of Manresa, where there was less immigration, it went from 47.4 per cent between 1785 and 1789 to 34 per cent in the subsequent five-year period.Footnote 48 When expectations worsened in times of crisis, families from outside the cities were less likely to see a future for their children as silk artisans and, if there were only a few apprentice positions available, families in the cities would be the first to hear about and ask for them. In conclusion, the crisis changed the labour market, which became more local, occupying fewer young people from the neighbouring towns, especially in Manresa.

Figure 4. Geographical origin of the apprentices of silk weavers of Manresa (1818–1843).

Figure 5. Numbers of apprentices in silk weaving in Barcelona and Manresa, 1785–1823.

A further indication of the crisis in silk was the suspension of payments by the manufacturers and traders. The silk masters and the companies which sold on credit in America saw how demand fell, payments were delayed and/or did not arrive as a result of the wars, which led to a stoppage of production and sales and were thus encouraged to recover, only partially successfully, the funds they had invested there (this trickle lasted for the whole of the first half of the nineteenth century). The result was predictable. The contraction in demand left the silk weavers and the women who prepared the fibres and wove the textiles without work, caused many small independent producers to go bankrupt and created difficulties for bigger companies. In Manresa, three companies, Pablo Sagristá and Co., Ignasi Parera and Co and Asols and Co, had between them cornered 75 per cent of exports at the end of the century. Nevertheless, they struggled and eventually disappeared.Footnote 49 However, despite the losses, the liquidity of the companies which survived eventually increased once they succeeded in being paid for the consignments sold.

In 1814, after the Napoleonic war, both the previous external and internal trading networks had been broken. For the Catalan silk masters, it was more difficult – and certainly more expensive – than before to obtain silk from Valencia and Aragon, their main source of supply. After the war, spun silk from Valencia increased in price because the traders monopolised it and because it was exported abroad.Footnote 50 Between May 1815 and February 1816, the cost of weft thread went up by more than 30 per cent.Footnote 51 Furthermore, according to contemporaries, the freedom to import foreign silk textiles led to a decline in Valencian production and, when it was restricted, contraband appeared.Footnote 52 These circumstances also harmed Catalan silk manufacturing.

The silk weavers of Barcelona and Manresa developed different strategies to overcome the crisis. In Barcelona, the production of silk textiles was maintained, attracting Catalan artisans from the sector who decided to continue with their trade. By contrast, contemporaries described the situation in Manresa as much bleaker, although the silk industry did not collapse entirely. In both cities, there is evidence of a clear evolution towards other products and above all, from silk to cotton which ended up being the dominant fibre, particularly in Manresa.Footnote 53 To emerge from the crisis, the Manresa silk weavers, in particular, had to adapt to new productive opportunities.

3.1. Adaptation to crisis in Manresa

The loss of the colonial market gave rise to a structural crisis in the Manresa silk industry. If in 1788 there were 509 silk weavers, in 1816 there were only 234, even though population levels do not seem to have declined between these dates.Footnote 54 The same decline in numbers of weavers is evident in the other silk guilds. Some craftsmen and merchants emigrated to Barcelona and those who remained had to convert to other trades.

The guild nonetheless continued to be active. There was a gradual reduction in the number of apprentices (271 between 1815 and 1845), as we have already said.Footnote 55 The number of masters’ agreements, by contrast, rose: 441 were granted between 1815 and 1850. In this period, it seems that masters’ agreements served a different purpose from that in the eighteenth century. The qualification of master silk weaver was a symbol of prestige and was even obtained by individuals who were no longer exercising the trade of silk weaver. Unlike in Barcelona, the fall in apprenticeships can be explained by the conversion of the independent workshops into modest family workshops which wove for third parties and did not need apprentices.

The first avenue of adaptation was when the most important silk weavers began to explore new opportunities. They were already familiar with cotton since the new fashions introduced this fibre into all kinds of textiles. Whereas silk, as discussed above, had become harder to obtain, cotton imports to the port of Barcelona recovered quickly. According to Sánchez and Valls-Junyent, by 1819–1820 cotton imports had returned to the level they had reached prior to the war.Footnote 56 Cotton was not as easily available in Manresa, which was some 13 hours’ distance from Barcelona along unsafe routes.Footnote 57 As a result, the cotton industry was initially concentrated in Barcelona. Nonetheless, new cotton spinning technologies had been introduced in various Catalan towns before 1808 – the year of the Napoleonic invasion – and stockings, ribbons and cotton pieces were woven with this fibre.Footnote 58 Therefore, Catalonia already had a cotton infrastructure and techniques for making and operating different types of looms and machines to spin cotton. Part of the capital recovered from colonial trade was thus devoted to setting up cotton spinning factories driven by hydraulic power which required a significant investment in fixed capital: a total of nine were built between 1801 or 1802 and 1817. Other silk producers believed that the future was in wool factories, also driven by hydraulic power.Footnote 59

One consequence of the silk-making crisis and a strategy for adapting to it was the emigration of many silk weavers from Manresa to Barcelona, where they established themselves and tried to develop their trade or to begin in the cotton industry. The addition of 24 silk weavers from Manresa to the Barcelona silk weavers’ guild, between 1825 and 1834, with special treatment, was likely to have been only the tip of the iceberg in terms of migration.Footnote 60 Both descendants of the big master silk producers and merchants of Manresa and previously unknown silk weaver families participated in this new, steady flow.

The first group of these immigrants included two pairs of brothers, Pablo and Carlos Torrens Miralda and Josep and Llogari Serra Farreras, heirs and descendants of the partners of Pablo Miralda and C°.Footnote 61 These are the most important examples in view of their initial wealth. Other examples of formerly large silk producers were Josep ArañóFootnote 62 and the Herp brothers.Footnote 63 These four examples moved into the cotton industry – some as traders –, abandoning the silk industry, and they invested in other businesses. For example, the former partners of the company Pablo Miralda did so in the wool industry, in Manresa, and Carlos Torrens, alone, in a soap factory in Barcelona.

The path taken by the masters from Manresa with little capital, by contrast, varied greatly. While the brothers Manuel and Josep Balet, and Andrés Subirá were able to consolidate their silk weaving workshop and moreover invested in the cotton industry, the family of Francisco Solernou Rosals was not as lucky. His case may be paradigmatic of the path taken by the less fortunate silk weavers of Manresa. He was the son and heir of the silk weaver Francisco Solernou Cots, resident in Manresa. In 1823, he appears in the Barcelona marriage register as a jove veler (silk weaver, but not a silk master), marrying a daughter of Isidre Riera Berdaguer, a ‘manufacturer from Manresa, resident in Barcelona for some years’. In the 1830s, he was mentioned as a master silk weaver in a notarial document.Footnote 64 The Solernou-Riera couple had four male children. In 1854, Salvador, one of the sons, was called a ‘weaver’, an ambiguous term since we do not know whether it means that he was a wage earner,Footnote 65 but we do know that his brother, Josep Solernou-Riera, was a ‘worker’ leader active during the Bienio Progresista.Footnote 66 In other words, the family appears to have experienced downwards social mobility over the generations.

The business history of these immigrants was sometimes complex and changing, as shown by the cases of Francesc Sala Amorós and his sons, and the family of Francesc Cornet Cirera. In 1829, the former had a small spinning cotton factory with six mule jennies in Barcelona.Footnote 67 Three of his sons, who were between 29 and 19 years old, worked in cotton spinning – two of them outside the paternal house –, while the youngest, Antoni, who was 17 years old, was an ‘apprentice’ in the gremi de velers of Barcelona. In the early 1840s, he may have lived in Mataró, further along the coast from Barcelona, but around 1845, he was living in Manresa as a partner in a factory with hydraulic power to spin cotton with mule jennies, while his sons were linked to cotton manufacturing in other parts of Catalonia.Footnote 68

The Cornets are an example of the importance of women within these manufacturing family structures. The family also moved between Manresa and Barcelona. In his memoirs, Francesc explains that his grandfather, a silk weaver, tired of the guard duty that he had to undertake in Manresa during the Carlist war of the 1830sFootnote 69 and the bad quality of the silk that he had to weave, went to Barcelona where he worked in the silk factory of Joan Escudé.Footnote 70 He earned a good living and decided that his family should join him in Barcelona. There, his wife and daughters played an important role, purchasing machines in order to make cords which they then sold to the haberdashers. Meanwhile, his son became a silk weaving apprentice. However, they later returned to Manresa, at his wife's insistence. After working for the Balet silk firm, again with bad quality goods and fed up ‘with working a lot and earning little’, Cornet decided to open a cotton ribbon workshop. In the second half of the nineteenth century, he was a noteworthy ribbon maker of Manresa.

A different adaptation to the crisis, and one which shows that crises could be opportunities for certain families, was investment in land. The crisis saw the return of significant amounts of circulating capital from the colonies. This return coincided with mounting levels of debt in the countryside as a result of the agrarian crisis of the first years of the nineteenth century. Some silk manufacturers with available capital invested in loans to indebted peasant families and in purchases of land. Eventually, these families left manufacturing more or less altogether to become rentiers. To give just one example, Vicenç Solernou invested 32,867 Catalan libras in real estate between 1794 and 1829.Footnote 71

In Manresa, however, perhaps the most striking adaptation to the crisis came from the independent workshops, those which, in the eighteenth century, had had minimum assets. They again formed modest companies based on family ties, sold on the internal market often for commission and marketed various cotton goods and blends, among which ‘vetes’ (a kind of ribbon) proved particularly profitable.Footnote 72 These new manufacturers of handkerchiefs and ribbons gradually accumulated capital and were able to take the lead in setting up the new generation of cotton factories during the next phase of mechanisation after 1840.Footnote 73 This evolution ended up consolidating the cotton industry in Manresa and left silk textiles in the background. Many former silk weavers worked for these companies from their homes and switched from silk to weaving ribbons.

Ribbons were not, in fact, a new product. Manresa had an active production of ribbons in the eighteenth century made from both silk and cotton, but after the crisis demand increased. When the principal manufacturers went over to the cotton industry, ribbon making that blended silk and cotton continued to be a predominant activity in the city. Some of the former weavers became modest ribbon manufacturers.Footnote 74 Many workshops wove both silk and cotton. The ribbon-makers’ guild adapted to this system by, from 1828, allowing silk weavers to become, without examination, master ribbon makers and to manufacture the ribbons that they wanted.Footnote 75 Three labour categories could be clearly seen in this period, arising from the former guild structure: first, the ‘owners’ who had a small fixed capital (the looms); second, the ‘operators’ who worked for them and third, the ‘manufacturers’ who had working capital, gave work to third parties and organised the marketing.

Workshops of silk weavers who did not go over to ribbon manufacture continued to exist in Manresa, weaving silk, cotton or mixed handkerchiefs for other manufacturers who then marketed them. However, all the evidence indicates that this sector of the industry was in decline, in contrast to what occurred in Barcelona.Footnote 76 Despite this, the guild continued to be operative, as shown by the creation in 1853 of the Mutual Protection Society for the purpose of assisting in the case of illness and lack of work Footnote 77 to defend the interests of the weavers, all male. Unlike ribbon making, silk weaving was in direct competition with the manufacture of cotton textiles. Mechanised looms gradually replaced the former handlooms, reducing the demand for labour. The silk weavers were thus obliged to choose between becoming ribbon manufacturers or being absorbed by the cotton factories which needed skilled male labour.

3.2. Adaptation to crisis in Barcelona

Whereas the Manresa silk industry, by and large, had to change in order to adapt to the crisis, the Barcelona silk industry saw two different responses: continuity of older forms of production on the one hand, alongside considerable innovation on the other. Even after the Napoleonic war (1808–1814), the complete loss of the colonial market of continental America (1810–1824) and the post-Napoleonic crisis, Barcelona silk weaving managed to maintain a certain vitality. The silk weavers’ guild saw a decline in numbers of masters and journeymen, but also the appearance of new surnames, indicating the emergence of new entrepreneur families.Footnote 78 In the 20 years from 1794 to 1814, the number of masters went down by a third. Of the 14 masters who had a workshop and a shop in 1794, only six were still active in 1814. Of the 43 who only had a work space in 1794, there were only eight still active in 1814 (17.4 per cent). However, this reduction in the number of masters and workshops was offset by the creation of 50 new masters between 1815 and 1819, a movement accompanied by an important arrival of young men as apprentices (Figure 5). Between 1814 and 1824, an average of 21.3 apprenticeship charters were signed each year and 121 master's charters were granted. This trend continued in the following five-year period.Footnote 79 Despite the complete abolition of guilds in 1836, apprenticeships continued to be recorded until the end of the 1840s, which suggests there was interest in knowing this textile technique, perhaps because this education was considered as vocational training which could also offer entry into the cotton sector.Footnote 80

In 1823, the number of silk weavers registered as liable for tax had increased by 55 per cent compared with those recorded in the guild register for 1814, a sign that the industry had recovered. However, by 1838, the number had gone down again, probably due to the concentration that was taking place in the sector, although the pattern of this process is not known. Twenty-three per cent of the surnames of silk weavers recorded in 1814 were to be found among the tax payers of 1854. The disappearance of the guilds, therefore, did not give rise to a multiplication of workshops, although it did help some of the journeymen to open their own workshop.Footnote 81 In short, the silk industry was maintained in Barcelona, attracting young men above all from the city itself and also a fair number from Manresa – and in a lesser proportion from other Catalan cities. Between 1835 and 1840, some 230 master's agreements were signed.

As in Manresa, however, innovation proved to be the main way of adapting to crisis for Barcelona manufacturers. Such innovation can be seen from the end of the eighteenth century, when some silk weavers, seemingly less affected by the loss of the American market than those from Manresa, began to develop new products. They focused on the production of gauzes and tulles, sometimes with cotton.Footnote 82 Given that these weavers had not accumulated capital to the same extent as the Manresa manufacturers, these initiatives were probably only possible thanks to the introduction of special cotton looms from France.

Innovation as a response to the crisis was already clearly demonstrated in the 1820s and 1830s with the introduction of some important technical developments in the sector. These were the installation of the first Jacquard looms in the 1820sFootnote 83 and introduction of new looms to make tulle mechanically from 1828.Footnote 84 Later, looms to make lace mechanically were introduced in the 1850s.Footnote 85 It is worth mentioning that, in this case, these looms used cotton more than silk, although the capital basically came from the silk sector. Another technical innovation was the modernisation of silk spinning, with the introduction of hydraulic power and steam-powered machinery in the years 1838–1841.Footnote 86 Furthermore, several Barcelona manufacturers installed a silk spinning factory with a steam-powered machine in Valencia, a city which continued to be the epicentre of the main silk-making region of Spain.Footnote 87

Two characteristics should be stressed here. The first was that adaptation to the crisis was in part due to the introduction of foreign technology, sometimes on the initiative of foreign artisans. The second is that the capital involved was provided by silk manufacturers, some of them now acting exclusively as merchants, with very little involvement of other commercial capital. The only exception was the Dotres, Clavé and Fabra company, one of the most important in the sector. None of these partners had ever manufactured silk directly, though Dotres commercialised silk from early on in his career and was the first to import French machinery to make silk tulle and then lace, having been exiled in Lyon after 1823.Footnote 88

In short, numerous family businesses ensured the survival and adaptation of silk production in Barcelona. Many had seen several generations of silk manufacturers, but the sector was also regenerated by the arrival of a considerable contingent of new entrepreneurs, some from Manresa, as discussed above. After a process of technical change and innovation over the nineteenth century, the Barcelona silk industry remained small in size, above all compared to the cotton industry, but by the beginning of the twentieth century was the most important silk industry in Spain.Footnote 89

4. Female participation in adaptation to crisis

Unfortunately, there is little that we can say about how the search for a new business or work opportunities affected women. The ending of guild restrictions in 1836 did not mean that women opened their own silk weaving workshops, because they did not have the capital to do so or the knowledge of the new technologies. However, it did represent a relief for widows who could maintain the family workshop without restrictions, for the independent female artisans who could have their own shops without fear of prosecution by the silk guilds and for the working-class women who could work as wage earners in these workshops without opposition from the silk journeymen. In the majority of cases, however, the continuation of the traditional business structure in family workshops into the post-guild period meant that there was no fundamental alteration in the position and the duties of women in the sector. They continued to contribute labour, capital and family and business ties.Footnote 90 The case of the Cornet women shows the important role that artisan women could play in helping to adapt to crisis. Their work, weaving cords with machines, was innovative and decisive for the survival of the family and maybe for the accumulation of the capital necessary to open the business of making cotton ribbons which was set up by the father in Manresa. There were undoubtedly other similar cases.

The crisis reduced demand for female labour in all sectors, including the silk industry. However, the development of the cotton activity opened up new opportunities for female wage earners, particularly from the 1830s. In the mid-nineteenth century, according to Ildefonso Cerdá's study of the working class, working-class women in Barcelona worked in traditional female occupations in the textile and service sectors.Footnote 91 It should though be stressed that they were also employed in jobs related to the Jacquard machine, introduced in the 1820s in the silk and cotton industry: they were rodeteras (bun makers), canilleras (warpers), fimbriadoras (fringe makers), tyers and weavers. All together, women were 4.3 per cent of the workforce employed by these machines. There were also a few women who wove stockings on looms (17.32 per cent of all stocking makers), a trade which had been reserved for men in the guild era.

In Manresa, women continued in the silk weaving workshops which survived; others were involved in winding in the cotton factories. In 1842, women were 59.8 per cent of the spinning workers in Manresa and, by 1855, 89.4 per cent of the members of the mutual aid Society of Female Day Labourers of the spinning mills of Manresa. Thus, a new labour structure was established in Manresa in the nineteenth century. While men wove ribbons at home, women spun in the cotton factories. This was the new model for many working families in the city in the mid-nineteenth century.

5. Conclusion

In the eighteenth century, the Catalan silk industry expanded, specialising in the production of simple fabrics with little technical complexity. Barcelona and Manresa were the two main centres but had different structures of production and wove different products. In addition, Barcelona had an important harbour and a more complex economic structure. Calicoes also became an important manufacture in Barcelona.

Although in both Barcelona and Manresa, silk manufacturing was based on independent family workshops regulated by guilds, the two cities saw the development of different kinds of silk enterprises. The Manresa silk weavers’ guild obtained the right to produce lighter fabrics – mainly handkerchiefs – than those woven elsewhere in Catalonia. This allowed the Manresa silk industry to conquer an important market. This expansion was accompanied by the creation of family-based companies that sold their own products but also those of other silk weavers. Some of these silk companies were able to accumulate important capital by expanding also into buying and selling other agricultural and manufactured goods, including colonial products. In Barcelona, by contrast, there were a few cases of partnerships between silk weavers who built up assets, but not on the same scale as the Manresa companies.

Subsequently, however, from the 1780s to 1830s a series of economic crises caused by the wars, poor harvests in the Iberian Peninsula, and the loss of the continental colonial market affected the production of silk textiles in Barcelona and Manresa. In 1814, after the end of the Napoleonic war, the Catalan textile external trade networks of the eighteenth century with Atlantic Europe and the Spanish colonies of America had practically disappeared and could not be rebuilt. However, this did not prevent the construction of other networks which guaranteed the arrival of raw cotton to feed the Catalan industry, while it was difficult to obtain silk from Valencia, traditionally the main supplier of silk to Catalan manufacturers. Catalan silk producers thus had to adapt to the new circumstances.

However, the economic crisis did not represent the specific disappearance of textile activity in Barcelona and Manresa. The adaptation to the crisis meant a change in the silk textile sector, but this change took a different form in the two cities. Barcelona consolidated its silk sector through innovation and the recruitment of artisans and capital from other Catalan manufacturing cities, largely from Manresa, and also developed an important cotton industry. Manresa specialised in the production of cotton ribbons and the mechanised spinning of cotton, maintaining a marginal silk activity in part through the manufacture of products that combined silk and cotton. Manresa continued to be an important textile centre despite the disappearance of the majority of the silk companies, the loss of capital, and the migration of a large part of its qualified artisans, mainly to Barcelona. The relaunching of Manresa as a textile town was due to the maintenance and development of the entrepreneurial spirit of many small and anonymous silk craftsmen and families, active already in the eighteenth century, and the emergence of new entrepreneurs, whose workshops often grew into new family companies. The men and women of Manresa were thus able to revive their city's economy, albeit not without human cost, particularly the migration of many male and female artisans and merchants.

Women played an important role in the Barcelona and Manresa silk manufactures as spouses and daughters of artisans in the family workshops and as salaried workers, although we have very little information about their work and the economic contribution made by their dowries. Nevertheless, we know that the ability of the silk industry in Manresa and Barcelona to adapt to the crisis and the new circumstances which governed the global market that followed was down to the efforts of families such as the Sala and Cornet families of Manresa. Above all, it was down to those individuals and families who took the risks involved in changing their occupations and even their place of residence.