INTRODUCTION

In ruthless times when savagery and fratricidal wars brought our beloved Cambodia to grief, it was not only the people who suffered misfortune.

— Prince Norodom Sihanouk, writing for the International Council of Museums (ICOM)Footnote 1

One of the lesser-considered consequences of armed conflict is the profound impact violence can have on the physical manifestations of culture and religion. To this end, the religio-cultural heritage of Cambodia was at the mercy of the barbarity of warfare during a tumultuous sociopolitical upheaval dating from the late 1960s through to the 1970s, which constituted, but was not limited to, the following series of violent episodes:

• American bombardment of Cambodia: “Operation Menu,” 1969–70;

• Cambodian Civil War, 1970–75;

• Democratic Kampuchea (the Khmer Rouge [KR] Regime), 1975–79;Footnote 2 and

• Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia, 1978–79.

While this article will examine American and Vietnamese military operations that have threatened Cambodia’s heritage, its main focus will revolve around the relationship between Democratic Kampuchea and Buddhist places of worship. As may be imagined, this was a relationship defined by belligerence; the abolition of religion and the spiteful obliteration and misappropriation of monuments, monasteries, and wats (temple-monasteries) occurred throughout every area of Cambodia during the Democratic Kampuchea Regime. Elizabeth Becker, one of the very few Western journalists permitted entry to the country during this time, observed that iconoclastic destruction and religious persecution were almost absolute, “with more devastating consequences for Cambodia than the Chinese attack on Buddhism had had for Tibet.”Footnote 3

In light of the insufficiency of existing literature on the matter, it is the aim of this article to examine the effect that war and successive political regimes have had on Angkorian temples,Footnote 4 from immediate conflict damage to the indirect repercussions of totalitarian rule. A particular corollary of identifying this damage will, I hope, offer some illumination on the otherwise opaque question of the KR’s day-to-day treatment of the ancient temples—for instance, as grain deposits, ammunition dumps, and quarters for soldiers. These insights should be incorporated into how we understand the functioning of the Regime’s political and military machine and how the temples and monuments fitted into this institutional architecture, both ideologically and materially. I have used Angkor Wat and the temples of the Angkor Archaeological Park as my primary illustrative example(s) throughout this article.Footnote 5

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The aforementioned four phases of violence were predominant on the political, economic, and social landscapes of this decade (1968–79) in Cambodia’s history. It is imperative to understand that these crises were connected to each other causally: the repercussive effects of each disaster initiated the next relentless sequence of chaos. In short, the American bombardment of 1969–70 set in motion a devastating chain of events that was to ravage Cambodia for over a decade; indeed, there is a unanimous agreement that the KR was “born out of the inferno that American [bombing] policy did much to create.”Footnote 6 Pol Pot’s Communist Party of Kampuchea ascended to power from the ashes of a battered and destabilized rural Cambodia to perpetrate unspeakable crimes against the Cambodian people, the horrors of which would eventually necessitate a Vietnamese intervention through invasion.

These successive episodes and the sociopolitical conditions behind the rise of the KR have been well documentedFootnote 7 and do not warrant much explication here. It is now understood that the interconnectivity of French Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) during the 1960s resulted in the region becoming helplessly tangled in a web of international geopolitical maneuvering, overwhelmingly defined by Cold War proxy politics. Cambodia’s place amongst these machinations was for a time non-partisan, although uncertain; in a diplomatic attempt to distance his country from the raging Vietnam War, Cambodia’s monarch, Prince Sihanouk, continuously defied alignment with the Communist and anti-Communist blocs that dominated Southeast Asia at this time. This neutrality, however, was short-lived as Vietnamese Communist incursions into eastern Cambodia became commonplace, with Viet Cong guerrillas seeking sanctuary and respite from their campaigns across the border. The American President Richard Nixon, pressured by American congressional dissent over the failure of a joint US-South Vietnam ground invasion in Cambodia, explicitly ordered a covert escalation of American B-52 bombing designed to destroy the mobile headquarters of the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA).

The situation reached a watershed as villages along the Vietnamese-Cambodian border were targeted by US aircraft in 1969–70 on suspicion of harboring Vietnamese communists. This produced a twofold effect: first, the bombardment pushed the Vietnamese deeper and deeper into Cambodia, unintentionally bringing them into greater contact with the KR with whom they discovered a mutual ideological conviction, and, second, the bombs drove an enraged Cambodian populace into the arms of an insurgency (the nascent KR), which hitherto seemed to have slim prospects of revolutionary success.Footnote 8 In tandem with this bombing, the United States moved behind the scenes to install the hard-line, anti-communist General Lon Nol, who, in a 1970 coup d’état, deposed the ineffectual Prince Sihanouk. The new US-backed republic, through authoritarian repression and bombing raids against anti-government resistance, gave the coalescent dissident forces of the KR a further raison d’être and prerogative to insurrection. After five years of brutal civil war, the Republican government was defeated in 1975 when the victorious KR inaugurated Democratic Kampuchea. The American aerial campaign initiated by Richard Nixon had thus inadvertently precipitated a Maoist, agrarian revolution and eventual genocide in which more than 1.7 million people perished. The anguish would only come to an end in late 1978 when the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia drove Pol Pot and his cronies into exile.

CAMBODIA’S RELIGIOUS HERITAGE

Amidst this strife, we must emphasize the centrality of heritage in a nation’s fate; culture, religion, history, and local communities inevitably become entwined in the broader matrix of national and international political, economic, and social states of affairs. With the establishment of the KR as a bona fide political entity, otherwise stable principles of community were violently uprooted and replaced with a national uncertainty of what constituted Cambodian culture and identity. On Day Zero, 17 April 1975—the day that Democratic Kampuchea officially came into being—2,000 years of Khmer history were immediately declared meaningless. In lieu of this cultural and historical void, the Regime endeavored to radically transform the country overnight with an inviolable plan for an agrarian, utopian cooperative that demanded total devotion to the state. The KR ensured that its subjects looked only to the future by enforcing a collective amnesia of its country’s pastFootnote 9. Jon Swain, the only British journalist present at the fall of Phnom Penh to the KR in April 1975, remarked that this dissolution of virtually all traditional Cambodian values occurred by “abolishing everything that was dear to the people, including money, property, religion, traditional marriage, normal childhood, books, music, medicine—even laughter.”Footnote 10

One of the prime targets of this societal deconstruction was Cambodian religion,Footnote 11 a “rich fusion of folk beliefs, Brahmanism, and Buddhism that had, for centuries, formed the basis of the Cambodian sense of order.”Footnote 12 As a typical Communist Party of Kampuchea slogan proclaimed, “[f]or the Angkar, there is no god, no ghosts, no [religious] beliefs, no supernatural.”Footnote 13 But the KR went a step further than merely proscribing religious belief: as a living doctrine, Buddhism was to be wholly expunged from Cambodian society through the liquidation of its living elements—the monkhood was terminated in a post-revolution bloodletting that victimized religious, ethnic, and racial minority groups.Footnote 14 Before 1975, there were approximately 60,000 Buddhist monks in Cambodia; after three years and eight months of KR rule, fewer than 1,000 survived and returned to their former monastery sites.Footnote 15 The Venerable Heng Monychenda, chairman of the Khmer Buddhist Research Centre in Bangkok, describes the sweeping extent of this repression:

Half of the pagodas were totally destroyed and many others turned into prisons, torture chambers and places of execution. Buddhist monks were forced to renounce their orders and many, including the Supreme Patriarch and several high-ranking monks, were put to death. Buddhist canons and scriptures were burned and statues of the Lord Buddha smashed.Footnote 16

As befitting the KR’s virulent communist ideology, the Regime’s programs of persecution virtually erased Buddhism from Cambodia. It is appropriate here, however, to bear in mind that the Regime was not the first group to perpetrate the destruction and vandalism of Buddhist material culture in Cambodia. For instance, the defacement of countless Buddha images was synonymous with the reign of the Hinduist Jayavarman VIII (1243–95). Almost two centuries after him, the temples of Angkor were repeatedly defiled by Siamese and Vietnamese invasions during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Ta Meas, a nineteenth-century Cambodian historian, observed of these medieval assaults: “Novices and priests also suffered because the vihāras [Buddhist monasteries] had been plundered. Gold and silver buddhas had been removed, and soldiers had set fire to many vihāras.”Footnote 17 Although digressive, these episodes of historic vandalism in Cambodia serve to illustrate how attacks of religious iconoclasm frequently target revered achievements and the material symbols of power, spirit, and unity. Ta Meas’s quotation contains striking similarities to the Venerable Heng Monychenda’s description of the KR’s anti-theistic procedures. Further parallels between the KR and the fifteenth-century invasions are evident: the vandalizing of Angkor by the Siamese aggressors of 1431 went “hand in hand with the removal of ideas, intellectuals, and skilled and religious men to Siam.”Footnote 18 This ominously foreshadowed much of the KR’s behavior centuries later, with the killing of “intellectuals” and not least in the Regime’s execution of “urbicide”:Footnote 19 the forced depopulation of Phnom Penh is by all accounts a textbook case of a “murder of a city.”Footnote 20

What these ancient and modern comparisons reveal is that important cultural locations—whether a city or monument—are often targeted because they represent the character and identity of an indigenous community. In this context then, culture is identity, and the KR’s attacks on Buddhist places of worship can be construed as intentional identity destruction. It is impossible not to view this excision of religious identity through a political lens; in no other communist state, including even China’s annexation of Tibet, has a materialist ideology been so fatally imposed at the expense of a spiritual tradition. While the usual communist dogmas were deployed in Cambodia—the notion that religion is the opium of the people and that the clergy took advantage of the people’s credulityFootnote 21—the Communist Party’s attacks on Buddhism surpassed the de facto Marxist notion that religion serves to disguise class relations. The Regime’s leaders and cadres went above and beyond the literal implementation of these communist concepts: by the complete elimination of one of the primary institutions that served as a source of Khmer identity and acted as a societal adhesive, the KR effectively created a new social order whose past was rootless. The history of the new Democratic Kampuchea utopia was to be written by the revolution alone.Footnote 22

THE FATE OF TEMPLES

With this gargantuan anti-religious impetus, how did the ancient, physical manifestations of Cambodian Buddhism fare? It must first and foremost be pointed out that the Angkorian temples escaped systematic destruction. They were affected, however, in other ways, from superficial damage delivered by conventional weaponry to the prevalent use of structures by soldiers. This is not entirely surprising considering that the temples were nuclei of everyday Cambodian existence—they served as places of social gathering, education, and religious life. Before 1975, most Khmer men became monks for at least a small part of their lives; even the young Pol Pot in the mid-1930s passed several months as a novice at Vat Botum Vaddei.Footnote 23 In one way or another, contact between the ancient structures and the Regime was inevitable.

A line of demarcation must be drawn here between the KR’s treatment of ancient temples and more modern wats; as this work has progressed, my attentions have metamorphosed to include considerations of these post-Angkorian structures because I believe they are crucial to understanding the wider context of the KR’s programs of cultural destruction. Thus, we see a striking dichotomy between the Communist Party’s preservation of earlier Angkorian monuments as a nationalist symbol with which to bind people to the Regime—they attempted to historically ground the ideology of an agrarian utopia in the ancient Khmer’s achievements—and, conversely, their methodical destruction of post-Angkorian temples.Footnote 24 Indeed, an integral part of the leadership’s strange doctrinal brewFootnote 25 was a romanticized vision of ancient Cambodian civilization; the temples and irrigation systems of Angkor were seen as the pinnacle of the country’s historic achievements and, as such, were spared as lasting symbols of collectivist glory. Without this prerequisite for immunity, little else was afforded such lenience, and the post-Angkorian shrines were open to annihilation. Of Cambodia’s 3,369 wats, more than one-third were destroyed between 1970 and 1975,Footnote 26 and the majority that survived were desecrated through use “as stables or granaries, prisons and execution sites or were partially destroyed in order to provide recycled building materials.”Footnote 27 These destructions were further fuelled by fears that functional monasteries and wats might harbor residue religious sentiment. It is interesting to differentiate here between the active elements of religion that would have been seen as dangerous by the Regime, in contrast to the ancient, more innocuous heritage that instead offered an opportunity for political legitimation through propaganda.

But perhaps the KR’s most ruinous legacy was its endorsement and practice of looting. The communists and their allies plundered bas-reliefs, statues, and other Angkorian artifacts to sell on the international art market, the proceeds of which financed their civil war against the Republican government. In addition, an unstable political situation brought about by the Vietnamese invasion of 1978–79 set the wheels in motion for the continuation of this looting well after the Regime’s demise. Vandals seeking profit have plagued Cambodia ever since: “[O]rganised antiquities trafficking largely started with the war but did not end with it.”Footnote 28 A number of excellent studies have amply covered this ground: Tess Davis and Simon Mackenzie’s forensic work on the underground networks in place behind looting is illuminating, as is the ICOM’s One Hundred Missing Objects.Footnote 29 This is perhaps the one area of the destruction of Cambodian cultural property that has been sufficiently researched.

DEFICIENCY IN THE RELEVANT LITERATURE AND THE AVAILABLE EVIDENCE

The remainder of the existing literature that has approached the relationship between Regime and temple has been far from clear and, in many instances, inadequate. A greater recognition of crimes against heritage is needed, if not to plug the discernible void of historical knowledge, then certainly as evidence for the prosecution of former KR members in courts of law. The legal process is simple: after the establishment of the spatial and temporal parameters of armed conflict, the principal evidentiary challenge is then simply to “show that items of cultural property were destroyed with the requisite knowledge or intent of CPK [Communist Party of Kampuchea] leaders.”Footnote 30 From a more humane point of view, it remains vital to document both the visible and invisible scars of monument and memory that are the remnants of a traumatic period in the psyche of Cambodia’s people—these must not be forgotten.

The failure of scholars to directly engage with the destruction of cultural property, and Buddhist heritage, in particular, may be ascribed to a certain obscuration of the relevant information; as the Cambodian Buddhist historian Ian Harris has stated, “the extent and the specific nature of Khmer Rouge damage to Buddhist material culture is difficult to quantify,”Footnote 31 while the records of this damage in question are not “as abundant as one might expect given the historical consensus that widespread attacks occurred on pagodas, mosques, churches, and various items of art and literature.”Footnote 32 Why has this been the case? Partial explanation may be found in Cambodia’s isolationist tendencies during the KR years; under the Regime, few were permitted to cross its borders, and almost no outsiders were allowed to visit the ruins of Angkor.Footnote 33 As a result, there was a vacuum of any corroborative news on Cambodia during the 1970s, which extended to a paucity of any written evidence regarding the destruction of cultural property. So complete was this information blackout that the existence of a nationwide prison-torture-execution system was unknown outside Cambodia until after 1979. Likewise, it was only during the 1979 Pol Pot / Ieng Sary trial that assertions began to surface that the KR had ordered the systematic obliteration of pagodas.Footnote 34 We simply had no idea of the country’s state of affairs, let alone the state of its monuments.

Evidence of cultural destruction that appeared post-Regime was, perhaps predictably in the throes of the KR’s downfall, often inaccurate. For instance, after the installment of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (the Vietnamese-controlled government), Vietnamese accusations were made that Pol Pot’s acolytes had destroyed most of Phnom Penh’s monasteries. This is erroneous. The American historian Michael Vickery has noted that the majority of the city’s wats survived unscathed except for minor damage and deterioration.Footnote 35 Moreover, Vickery is critical of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea’s official estimate of 47 city wats having been razed, when, according to the demographer Jacques Migozzi, only 24 such structures existed in the first place.Footnote 36 It is quite possible that the People’s Republic of Kampuchea inflated the figure in order to exaggerate the KR’s crimes. Whether this inaccuracy arose from oversight or the deliberate forwarding of an agenda is beside the point; concrete and reliable information was hard to come by in the years immediately following the demise of the Communist Party.

Angkor Wat’s survival of the KR’s tenancy of power, more or less completely intact, has also distorted our judgments of what happened to other temples. As the magnificent complex has so long dominated perceptions of ancient Cambodia, one could mistakenly presume that its relative un-harm during the years of violence was somehow a totemic representation of Cambodia’s monuments as a whole: Angkor survived, therefore everything else must have too. This is entirely fallacious—my own suspicion is that premature conclusions have been automatically extrapolated from Angkor Wat’s immunity and that, as a result, the fortunes of other, less prominent temples have shrunk into invisibility. It is easy to forget that the complex is just one of many; there are estimated to be in the region of 4,000 known prehistoric and historic sites, only a fraction of which have been thoroughly surveyed.Footnote 37

In some ways, the failure to launch inquiries into the state of these “other” temples may be put down to the continuous (and commendable) attempts to seek rational explanation of the KR’s more heinous injustices. This deflects attention away from tangible heritage. National resources such as the Cambodian Genocide Programme at Yale University and the Documentation Centre of Cambodia (DC-Cam) have traditionally focused on recording crimes against humanity rather than crimes against cultural property. It only recently that DC-Cam has begun looking into cultural destruction as an atrocity crime. This preoccupation with genocidal crimes has extended to Cambodian law (and especially the Extraordinary Chambers in the courts of Cambodia) where the incrimination of former KR cadres for crimes against cultural destruction has been pushed to the periphery of the Cambodian legal agenda. As Sarah Thomas has made clear in her work, prosecutors have faced difficulties in “establishing the criminal responsibility of former leaders for destruction of such [cultural] property” in spite of the methodical program of cultural destruction that the Regime pursued.Footnote 38 It seems that this nascent area of Cambodian criminal law has been unable to unfurl its full judicial capability and that what prosecution has actually taken place has had little exactitude on what these crimes actually constitute.Footnote 39

Investigation has been further impeded by the remote nature of many of these religious and cultural sites, some cut off from the world for decades due to difficult and dangerous terrain and accessibility—that is, poor national infrastructure, impenetrable jungles, left-over landmines, and unexploded ordinance. The perpetual threat of the KR, driven underground and practicing guerrilla warfare well after their downfall in 1979, has also posed problems. It has only become possible to conduct a rigorous investigation of Cambodia’s isolated antiquity with the reopening of the nation’s borders in the 1990s. Encouragingly, the subsequent influx of foreign relief officials, journalists, and scholars has meant an increase in valuable evidence. And, yet, while this new information is undoubtedly available, no one has capitalized on it and offered the data in a compilation or article; there has not been a single, significant work that exclusively deals with the subject of war and Cambodia’s ancient heritage.

The literature is especially incongruous in its silence on Buddhist monuments. Of the scholars who have touched on the subject, Ian Harris’s chapter on Buddhist material culture under the KR provides the most complete picture to date, though it makes little mention of Angkorian monuments.Footnote 40 Although there are a multitude of glancing references on damage to Buddhist heritage in many other works, authors seem only to briefly cite a figure or single sentence and then move quickly on. These shallow references contain non-existent citations for any data used and a certain vagueness about the detail of destruction. The standard works on life under the KR provide only cursory detail.Footnote 41 More encouraging results have materialized as a by-product of investigations into genocide. DC-Cam’s ongoing mapping projects have identified many Buddhist pagodas, and other religious buildings, that have been defaced and converted into prisons between 1975 and 1979.Footnote 42 These findings have been corroborated by interview transcripts of tribunals and the testaments of survivors and former cadres who reaffirm that Communist Party of Kampuchea forces were engaged in the widespread destruction of mosques, churches, and pagodas.Footnote 43

Documents from the 1979 tribunal also include extensive reports of this destruction of cultural property,Footnote 44 which is again confirmed by numerous interviews and RenakseFootnote 45 petitions.Footnote 46 The petitions in particular have been especially illuminating; for example, a surviving monk named Unn Tep asserts that the cadres of the Communist Party of Kampuchea razed Buddhist temples, religious schools, and hospitals as well as other attached facilities throughout the Siem Reap area.Footnote 47 It should be noted that these discoveries have been a natural consequence of wider investigations into genocide and mass graves and not primary research.

INTERNATIONAL HERITAGE AND ARMED CONFLICT

Sadly, cultural property destruction continues to make headlines around the world. The recent armed conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa and their impact on cultural heritage in that region—most notably, the Islamic State’s atrocities in Syria and IraqFootnote 48 and the Muslim fundamentalists attacks on Timbuktu in MaliFootnote 49—have raised major concerns among international communities. The long shadow cast by totalitarian regimes continues to ensure that war will always have a future and that this future will always have adverse implications for international heritage. For this reason, the safeguarding of cultural property in hostile situations remains at the forefront of the conservation agenda,Footnote 50 the results of which have been a concerted effort to surround collective world heritage with a firm ideology of conservation and preservation. This, however, may well be in parenthesis for the simple reason that the political motivations of states, governments, and societies that often leads to war will always eclipse the consideration of culture.

Direct Conflict Damage

We may categorize the damage that warfare is capable of inflicting on tangible heritage as either incidental or intentional. While military misadventure was all too often culpable for collateral, or incidental, damage in Cambodia, many sites at Angkor have also been the targets of intentional vandalism by both soldiers and civilians.Footnote 51 This raises problems in separating incidental from intentional acts of iconoclasm and presents difficulties in pinpointing dates and perpetrators. Sources or allegations may insist that a bas-relief was intentionally vandalized by guards or soldiers, but it may just as well have been hit by stray bullets in a firefight: accounts vary. I should accentuate here that “confirmed” iconoclasm is not always “in and of itself a sign of absolute hostility to religion”;Footnote 52 many of these cases should be treated as instances of malign individualism (seemingly arising out of boredom and indifference) rather than as evidence of any state-sponsored programs of intentional destruction.

As previously stated, the existential preservation of Cambodia’s Angkorian-period heritage was never in question—however, the seriousness of incidental and superficial damage—that is, small-arms impact—to the monuments has become, in retrospect, all too evident. My inspection of the major temples of the Angkor complex reveal that eight out of the 20 major sites surveyed have been impaired by projectiles: Angkor Wat, Banteay Kdei, Banteay Srei, Krol Ko, Phnom Bakheng, Phnom Bok, Preah Khan, and Srah Srang.Footnote 53 The principle cause behind this damage was the recurrent construction of military bases (by all factions) in proximity to, or within, temple complexes: “monastery compounds made good barracks,”Footnote 54 and commanders often requisitioned the Angkor temples that were located in the deep jungle. Such monuments are often, by nature, of military value because of “height (snipers), location, or strategic use, i.e. for weapons that can be hidden or stored; [and] the same goes for prisoners and hostages.”Footnote 55 In particular, elevation was an important determinate in assembling these bases; the raised hill temples of Phnom Sampeau, Phnom Bakheng, Phnom Bok, Phnom Kulen, and Preah Vihear were all appropriated because of their height. Of the 20 sites surveyed, 11 were used, in one form or another, as military stations, and two had been used as prisons and “re-education centres.” The defensive use of landmines, usually in connection with a base and planted on the periphery of temple complexes, has also become apparent from this survey. The ubiquity of these anti-personnel explosives is staggering; the Siem Reap division of the Cambodian Mine Action Centre alone has uncovered approximately 25,000 mines and 80,000 units of unexploded ordnance (abandoned munitions or shells) from the Angkor Park.Footnote 56

This is a self-explanatory, but important, point to make: when a military detachment fortifies a site, it immediately exposes the location’s ancient heritage to the consequences of conventional warfare. To this end, the Cambodian Civil War (1970–75) and the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia (1978–79) can be isolated as periods during which temples were most in jeopardy.Footnote 57 The abandonment of monasteries during this time is especially indicative of this issue: according to one source, 997 wats—about one-third of all wats in the country—were disabled between March 1970 and June 1973Footnote 58 during some of the most ferocious fighting of the Civil War. Both aggressors in the conflict were accountable for the varying degrees of damage done to these pagodas; indeed, we must remember that the Republican government was often complicit in acts of cultural destruction, owing to the American and “Lon Nol-ian” bombings that targeted temples harboring guerrilla fighters.Footnote 59 As Ian Harris has stressed, “responsibility for the destruction has often been uncritically assigned to the communists.”Footnote 60 Apropos of this, the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea in exile published two “Angkor Dossiers” after the Vietnamese invasion (see Figure 1) in which we are informed that the 1970–75 Civil War did “very little damage to the temples”; that the KR “had not forgotten Angkor, but cared for it with 2,700 people” and that the Vietnamese Heng Samrin government jeopardized the monuments through pillage and the proximity of their military installations.Footnote 61 These assertions can be dismissed as KR propaganda; in reality, each army—whether KR, Republican, or Vietnamese—sought defensive havens in places of worship, with each being answerable to the disfigurement of cultural property.

Figure 1. The two “Angkor Dossiers” of 1982 and 1983. Both covers show Khmer Rouge cadres outside an Angkorian temple, probably Angkor Wat (published by the Délégation permanente du Kampuchea Démocratique auprès de l’UNESCO, quoted in Falser Reference Falser and Falser2015, 241).

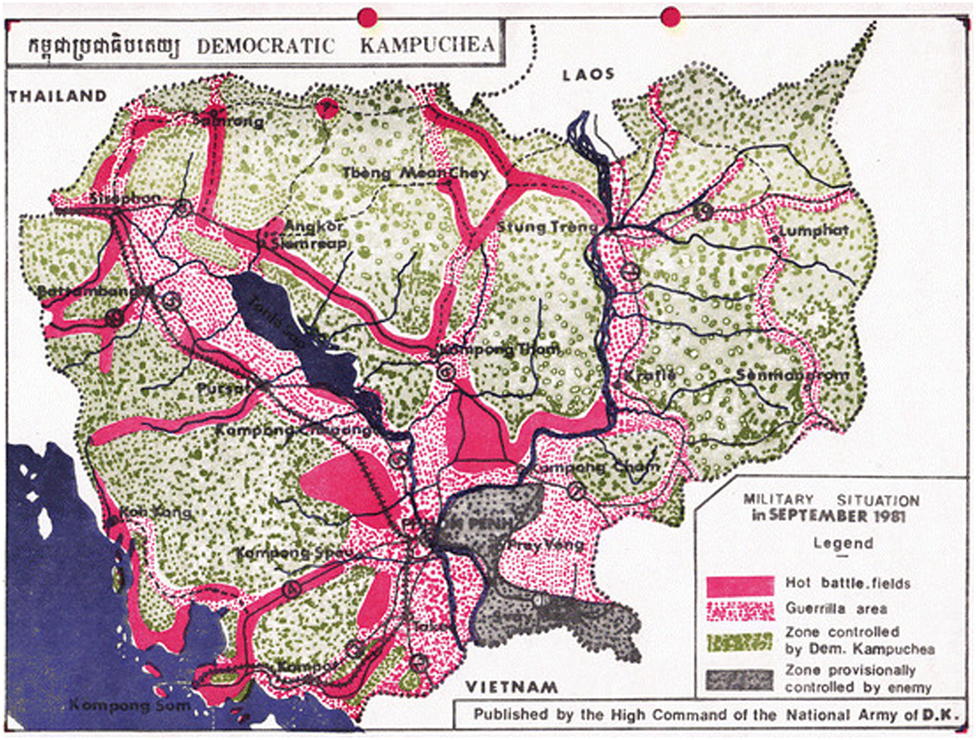

One facet to consider here is “conflict zones” and how the geographical location of places of worship, relative to regional fighting, increased or decreased their liability to risk (this is also pertinent in the consideration of American bombardment) (see Figure 2). The Angkor Archaeological Park (AAP), for example, was exceptionally susceptible to skirmishes and larger pitched battles throughout the 1970s because of its position in a strategically important corridor of the Siem Reap region. The aforementioned “Angkor Dossiers” acknowledge that the area around Angkor was seen as a highly valued asset to hold and that the defense of the region was “a preoccupation for all Khmers.”Footnote 62

Figure 2. A 1981 battle map of conflict zones including the section of Angkor (in the northwest of the country) placed dead center of a “hot battle field” (taken from Délégation permanente du Kampuchea 1983).

In fact, the whole of northwestern Cambodia was of strategic importance (for reasons I will cover presently) and especially so after 1979 with the KR’s transformation into a guerrilla fighting force. After the collapse of the Regime, a number of KR strongholds were set up in these northwestern provinces, advantageous topographically as remote mountainous regions and geographically as the furthest possible distance from the Vietnam border, factors that suited the newly formed government in exile. The KR succeeded in establishing resistance bases in the provinces of Battambang, Siem Reap, and Oddar Meanchey along and across the Thai border.Footnote 63 An apposite example of the inaccessibility of these outposts is Preah Khan, its extreme isolation contributing to the fact that it was one of the last remaining pockets of KR rebel resistance. Unfortunately, the site still bears the scars of quartering an underground army; there are bullet holes peppered throughout the complex and tank track marks incised in its sandstone gateways.Footnote 64 Similarly, Phnom Kulen was a KR-controlled sanctuary for as long as 20 years after the Vietnamese invasion of 1979, its resistant longevity attributable to its proximity to Anlong Veng, a district on the very edge of Cambodia’s border with Thailand and a long-standing nucleus of KR power. It was only in 1998 that the last cadres were forced to descend from this inaccessible plateau.Footnote 65

As part of the KR’s morphing tactics as an underground insurgency, militias began to regularly attack the city of Siem Reap and the temples of Angkor after 1979, posing a constant threat to the Heng Samrin government in Phnom Penh. The northwest of the country remained vulnerable to this form of asymmetrical warfare, characterized as it was by more mobile, roving battalions of soldiers with a proclivity for attacking temples in the region. The KR pamphlet Undeclared War against the People’s Republic of Kampuchea,Footnote 66 published after the Vietnamese invasion, reported that, while the newly installed People’s Republic of Kampuchea government was preoccupied with fighting the exiled Democratic Kampuchea strongholds on the Thai border, the KR concentrated their “guerrilla war efforts in the core zone around the Tonlé Sap lake, including the Angkor zone.”Footnote 67 Somewhat astonishingly, these attacks have continued for as long as a decade after the KR deposition, the most recent example being the 1993 assault on Banteay Srei.Footnote 68

Small-Arms Fire (Bullets, Shelling, and Mortar)

I would like to briefly revisit the discussion concerning “conflict zones”; it is worthwhile expanding on the AAP’s vulnerability to violence as it was located in the dead center of one of these “zones” throughout the intense fighting of the 1970s. Indeed, during the Civil War, a significant portion of the AAP was transformed into what was essentially a large, “pitched” battleground between entrenched republican and communist armies. The resulting small-arms damage that befell several temples is omnipresent: walls are pocked with the bullet holes from small-caliber machine guns, and parts of the temples are scorched and shattered from rocket-propelled grenade explosions. At Angkor Wat, a poorly aimed republican artillery shell has ruined a pavilion and, in the process, a section of an important panel depicting a scene of the Army of Suryavarman II,Footnote 69 while mortar fire has damaged one of the complex’s entries and also destroyed part of the south gallery.Footnote 70

The fighting took place throughout the AAP, and, as tactical necessity dictated, the Angkorian monuments were often the center around which a garrison was constructed. The so-called “Battle of Angkor Wat” in the early part of 1972 illustrates just how extraordinarily enmeshed these ancient temples were in the wider Civil War. The battle in question involved a thousand-strong North Vietnamese regiment (the 203rd Regiment), complemented by a KR contingent of 600 men, both deeply entrenched in the AAP and in control of a vast swathe of territory.Footnote 71 The communist coalition had used the Angkorian monuments as the foundation for their lines of defense—what the journalist Tillman Durdin calls the “Angkor defence perimeter”—and established part of their headquarters in Angkor Wat: “[A]round the colonnaded corridors of the 12th-century [temple] the Vietnamese have eight blockhouses, all of stone and sandbags,” while the main tower was used as a radio mast for communications (see Figure 3).Footnote 72 Within the greater Angkor Park, there were a further two barracks: one at Angkor Thom and the other at Srah Srang (“Barracks 479” under the control of the Vietnamese).Footnote 73 It is also likely that Krol Ko formed part of this interconnected matrix of temple fortifications: the 217-foot-high hill provided an ideal location for reconnaissance and “the monitoring of military activities within Angkor Park, including a direct line-of-sight to the airport runway.”Footnote 74

Figure 3. Khmer Rouge troops occupy Angkor Wat, circa 1972 (Forbes et al. Reference Forbes, Henley and Hinshelwood2011, 147).

This defensive network, with the Angkorian temples at the heart of fortifications, was so well established that the 1972 offensive by the Forces Armées Nationales Khmères,Footnote 75 designed to oust the communist occupiers from Angkor, was unsuccessful despite a superior number of 6,000 Republican troops mounting an attack on the 4,000-strong NVA and KR force.Footnote 76 Wilfred Deac, an American government official attached to the US embassy in Cambodia in 1971, has lucidly outlined the details of this protracted battle. Moreover, he has usefully brought to light a particularly bellicose episode of this engagement—namely, that of the aerial bombing of Phnom Bakheng (and the communist coalition soldiers buttressed in its grounds) by the Khmer Air Force after Republican troops had radioed “North American T-28 armed trainers [who] loosed napalm and high explosive onto positions 600 feet from the venerable temple.”Footnote 77 It is plain to see from this, and innumerable other examples, that the most ancient of Cambodia’s edifices were often on the precipice of annihilation with these battles raging in and around the AAP; it is miraculous there was not more damage.

Aerial Bombardment

On the river many monasteries were destroyed by bombs. People in our villages were furious with the Americans; they did not know why [they] had bombed them. Seventy people from Chalong joined the fight against Lon Nol after the bombing.

— Ben Kiernan’s interviews with Chin Chhuon, Chhal Chhoeun, Khlm Veng, and Yem YiemFootnote 78

As the earlier discussion may testify, it is now abundantly clear that the indiscriminate and unlawful American carpet bombing of Cambodia in 1969–70 engendered the conditions that spawned the KR, bestowing the leadership of the nascent Communist Party of Kampuchea with the means for a potent recruitment drive and, eventually, with willing volunteers ready to take up the communist cause. A by-product of this bombardment was, inevitably, the widespread collateral damage done to Cambodian cultural property. How could it not have been? The devastating effect of American firepower had previously been seen on Vietnamese heritage during the Vietnam War;Footnote 79 in the face of this powerful aerial capability, what chance did the material structures of religion stand (Figure 4)?

Figure 4. “Hot-spot” spread of US bombing targets (Kiernan and Owen Reference Kiernan and Owen2015).

As with bullets, the ramifications of American bombardment on tangible Buddhist heritage has often been difficult to quantify, notwithstanding the widespread structural damage to villages and towns in the Cambodian provinces close to the Vietnamese border.Footnote 80 It is only recently that the great scope of these sweeping air attacks has become fully apparent. The previous uncertainty has been remedied, in part, by the disclosure of past American military action by Bill Clinton in a de-classified, but as yet incomplete, database detailing the records of the US Air Force bombing of Indochina from 1964 to 1975. The documents indicate that 2,756,941 tons of ordinance were dropped on Cambodia in 230,516 sorties over 113,716 sites, most of which remain poorly identified.Footnote 81 The tonnage has swelled to nearly five times the previously cited figure, now significantly more than the estimated 2 million tons dropped by the Allied Powers on Axis forces during the length of World War II: “Cambodia may well be the most heavily bombed country in history.”Footnote 82 At the mercy of these astonishing figures, collateral damage was immeasurable and inevitable. Fortunately, with the exception of Phnom Chisor, the main Angkorian monuments, by virtue of their geographic location, escaped the aerial destruction (see Figure 4). The eastern half of the country, on the other hand, was repeatedly brutalized with a great number of wats and monasteries reduced to rubble (see Figures 5 and 6). The long list of pagodas demolished in the aftermath of these bombs have only been partially documented and remain too extensive to delineate here.Footnote 83 Without unfettered access to the problematic cache of declassified American documents, we will struggle to fully and precisely record the damage.

Figure 5. A devastated religious structure, probably a monastery, date and location unknown (photograph courtesy of the Documentation Centre of Cambodia).Footnote 84

Figure 6. Local famers reported that the damage to the site’s modern Buddhist wat was caused by US bomb damage, still unrepaired in 1988. Location unknown (photograph courtesy of Kiernan 2017).

The American modus operandi that materializes from these reports is one of an aerial campaign whose sole objective was to strike communist-affiliated targets at any cost; the preferred method for achieving this was carpet or saturation bombing while the favored instrument was the long-range B-52 Stratofortress heavy bomber. Unguided payloads were often dropped in the vicinity of villages and pagodas, typically resulting in numerous casualties and, in many cases, the eradication of the local pagoda. These stratagems remain in complete contradiction to the retrospective provisos made by former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger: “[A]ir operations were subject to the rules of engagement that prohibited the use of B-52s against targets closer than one kilometre to friendly forces, villages, hamlets, houses, monuments, temples, pagodas, or holy places.”Footnote 85 Without doubt, these “rules of engagement” were incessantly and remorselessly breached. Any red tape was meaningless; as the historian Ben Kiernan has pointed out, we know definitively that the US Intelligence Community was aware as early as 1970 that many of the communist “training camps” that the US Air Force, in close collusion with the Lon Nol regime, had bombed were, in fact, insignificant political indoctrination sessions held in village halls and pagodas.Footnote 86 The US Air Force policy in Cambodia was unsystematic at best, its approach underpinned by operations on targets of indeterminate intelligence. One such example was Wat Preah Put Nippean (Kong Pisei district), which was subject to an aerial strike “after government forces heard stories of people bringing food to the wat. It was thought that they were supplying food to communists.”Footnote 87

The Vietnamese invasion, by contrast, was a more civilized affair. With the exception of Prasat Chen (Koh Ker complex), parts of which were wrecked by bombs in clashes between the Vietnamese and KR, there is little evidence of aerial collateral damage (see Figure 7).Footnote 88 An extract from a Vietnamese brigadier general’s memoirs reveals an acquaintance with the need to protect cultural heritage: “While operating in Cambodia ... special emphasis was placed on protecting the lives and properties of the Cambodian population, to include pagodas, temples, holy places of worship and historical relics. The use of airstrikes was subject to careful consideration.”Footnote 89

Figure 7. The bomb-damaged temple of Prasat Chen in the Koh Ker complex, 2013 (photograph courtesy of Miura Reference Miura, Hauser-Schäublin and Prott2016, 29).

“USE”

Application

From the Khmer Rouge seizure of power in 1975. … Buddhism was proscribed.

— Keiko Miura, Reference Miura, Hauser-Schäublin and Prott2016 Footnote 90

The KR’s victory on 17 April 1975 over the Khmer Republic marked the official formation of Democratic Kampuchea. In unconstitutionally seizing the right to rule from the incumbent and legitimate government, administrative power was placed firmly in the hands of the communists; the future of all temples, wats, and monasteries that formed the spiritual mesh of the country hung precariously in the balance. To some extent, their fate went hand in hand with the ideological objectives that determined how the state would be governed. How then would these ancient religious sites be utilized by the Regime as dictated by their ideology and as practical necessity saw fit?

As the somewhat oxymoronic Article 20 of Democratic Kampuchea’s constitution, disseminated in 1976, declared: “Every Cambodian has the right to worship according to any religion. Reactionary religion, which is detrimental to Democratic Kampuchea and the people of Kampuchea, is absolutely forbidden.”Footnote 91 The consequences of this article were devastating: between October and December 1975, almost all monasteries still active in the country were closed. A self-congratulatory Communist Party document from September 1975 gives some idea of the suppression: “90 to 95% of the monks have disappeared. … Monasteries, which were the pillars for monks, are largely abandoned. … In future they will dissolve further.”Footnote 92 The KR would profit from this decline. Once Cambodia’s principle theism was successfully quashed, the empty, material shells of religion could be salvaged and put to better use. This fulfilled two concurrent KR designs:

1. The end of temples as places of worship would become an intentional metaphor for the death of religion—what better place to tear out of the roots of an idea than its physical manifestations.

2. The urbicide or “death” of cities and a short supply of suitable administrative buildings in the countryside presented problems for the KR. Despite the Communist Party’s fundamentally anti-urban inclinations (architects and architecture had no place in their society), it still required buildings to carry out the governance of the country, and part of this role was to be fulfilled by sequestered temples.Footnote 93

As I have repeatedly stressed, the more ancient monuments, as symbols of past Khmer glory, were afforded an umbrella of protection. On the other hand, the Regime’s contemptuous predisposition toward structures that housed the emblems and practices of living religion meant that post-Angkorian wats and monasteries suffered disproportionately in the KR’s new policy of property appropriation; thus, when the Serbian journalist Dragoslav Rančić was permitted a two-week tour of Cambodia under the KR, he remarked: “[W]e saw pagodas turned into storage houses for rice or into barns for storing farm equipment” but maintained that the Regime preserved the Angkor Wat complex as a “national shrine.”Footnote 94

Functional Use

As one of the fulcrums of Cambodian national existence, the temple represented a center of social gathering, education, and religious life—in essence, a “reservoir and transmitter of Cambodian culture.”Footnote 95 The newly installed Democratic Kampuchea capitalized on this centrality as a means of asserting administrative control. Pagodas were seized for various bureaucratic functions, with some becoming local economic bureaus (mandīr setthakicc) and others becoming district offices.Footnote 96 These wats, as nodes on the intersections of daily Cambodian life, increasingly came to be used as practical tools by the KR (although they always remained dispensable to the Regime). One dimension of this practicality was the deployment of older temples (usually Angkor Wat and Banteay Srei) in a diplomatic capacity; in a carefully choreographed display showcasing the splendors of Angkor and designed to woo the visiting dignitaries of international allies, the KR projected a fabricated sense of stability, prosperity, and culture to the wider world (see Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 8. The alternative reality the KR chose to present to the world; a dance troop of smiling cadres at Banteay Srei. Photograph courtesy of the Documentation Centre of Cambodia (Dy Reference Dy2007, 31).

Figure 9. Democratic Kampuchea leaders with an unknown foreign delegation. Date unknown. Photograph courtest of the Documentation Centre of Cambodia (Dy Reference Dy2007, 56).

In spite of this, Angkorian monuments were usually exempt from the menial dutiesFootnote 97 that wats were assigned on an ad hoc basis by Communist Party officials. These “fit-to-function” roles were varied: from rice storage facilities, administrative headquarters, and farms to vegetable-growing patches and mechanical workshops.Footnote 98 Abandoned pagodas were often dismantled to take advantage of recyclable materials, most often iron girders and bricks that could be reprocessed in construction projects.Footnote 99 In more martial matters, the military requisitioned structures for logistical use: highly elevated wats, like Vat Ek and Phnom Sampeau, were used as watch posts, while monasteries along supply lines—Ta Muen Thom, for example—were transformed into depots.Footnote 100 These functions, of course, took place alongside the responsibilities of barracking and training troops: 250 soldiers of Battalion 101 were based at Wat Ployum and cadres from the 704th Special Forces Battalion (of the KR) were given special training in the Watt Langkar compound in Phnom Penh (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. Wats were used as places of training. Here, communists practice grenade throwing at an unidentified wat, 1970 or 1971. Photograph courtesy of the National United Front of Cambodia (Harris Reference Harris2013, 106).

There are several indispensable sources available that record the various ways in which wats were put to use by the KR. The first is embedded in the 1979 Pol Pot / Ieng Sary trial, during which Tep Vong (the country’s Buddhist leader) detailed the fate of nine Siem Reap pagodas.Footnote 101 The second, from the 1986 Indochina Studies Program Project of the US Social Science Research Council, has shed light on the fortunes of 10 monasteries in Battambang, 21 in Takeo, 15 in Kampong Cham, and a few select pagodas of Preah Vihear province.Footnote 102 Aside from their usefulness as a means of observing the operational logistics of the KR, these case studies have thrown up questions of accountability regarding cultural property within the Regime’s hierarchy. What ranks in the KR power pyramids had the seniority to authorize the destruction of a wat? An illustrative case is brought forward by Ian Harris who has recorded the testimony of a former cadre and prison chief called Prum Preung: “Orders, including those to demolish pagodas came from a high level within the Khmer Rouge and were delivered by letter to the district. From that point on, they moved downwards in oral form, so that he [a foot soldier] never knew who formulated the policy in the first place.”Footnote 103

It is apparent that, after the Communist Party of Kampuchea’s victory in 1975, we see the enforced secularization of monasteries and pagodas. Their association with religion thus severed, and their function recast, wats were consequently designed to be broadly utilitarian, providing whatever facility the Regime deemed necessary. The expropriation of these places of worship demolished one of what Ben Kiernan calls the three fundamental pillars of Cambodian life—those of the Buddhist religion, the family unit, and the peasant farm—that were so important to communities.Footnote 104 It is hard to escape the underlying impression that this reorientation in the “character” of temples, from warm benevolence to machine-like indifference, served as a powerful metaphor for the abandonment of faith that was to be replaced with a compulsory belief in a cold and alien state.

Propaganda and Ideological EmblemsFootnote 105

One aspect of the idea of collective or social memory, initially developed by the French philosopher Maurice Halbwachs (1992), postulates that “mnemonic sites” of indigenous importance, through tradition and memory of event, “anchor a community’s identity in space and make possible its perpetuation across time.”Footnote 106 In many ways, Angkor represents this mnemonic connection to Cambodia’s past and, as such, is intrinsically tied to Cambodian identity. Elizabeth Becker elaborates that “the touchstone of Cambodian history, of Cambodia’s identity, is the temple complex at Angkor. ... [The temples are] visible reminders that Cambodia was once the premier state and culture of the region.”Footnote 107 For better or worse, the KR were compelled to confront Angkor’s immense presence; it was simply impossible to ignore. And so the Regime fed its propaganda machine many of the myths, rituals, and symbols that originated, and were maliciously culled from, the Angkorian past.Footnote 108

Ironically, this expedient use of cultural inheritance was facilitated by colonial France’s careful historiography of the country.Footnote 109 The French conquest of Cochinchina, and the subsequent protectorate established in the Kingdom of Cambodia, paved the way for the reacquisition of the provinces of Battambang and Siem Reap (the home of Angkor) from Siam in the Treaty of 23 March 1907.Footnote 110 The territorial recovery opened the floodgates of French scholarship; by 1975, French explorer-academics had exhaustively surveyed the ruins of numerous Khmer temples.Footnote 111 Moreover, the formation of the École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO) in 1898 was also to play a pivotal part in furthering the knowledge of Cambodia’s past.Footnote 112 This important conservation body, supported by rigorous scholarship, had made significant contributions to the forensic clarification of Angkor’s mysteries—in particular, through the decipherment of ancient inscriptions, the refinement of chronological frameworks and the crystallization of ancient Angkorian notions of law, religion, and society.

This national enlightenment, while reintroducing the nuances of Khmer history to its people,Footnote 113 also endowed Cambodian leaders with a reinvigorated political vocabulary that idealized their distant and glorious past, the latent power of which would be instrumental to the Regime as a tool of indoctrination and political spin. To some extent, this politicized exploitation of history was anticipated by the modern Cambodian royalty and especially by King Sihanouk himself who harnessed ancient notions of Cambodian autocracy—the “deva-raj” or “god-king”—by the continuous and favorable comparison of himself with the Angkorian monarch Jayavarman VII.Footnote 114 In doing so, he set a precedent that was to be adopted in time by Pol Pot, the secrecy of the KR’s enigmatic leader only adding to the quasi-deific illusion of a “god-king.”

Having said that, it was the Angkorian temples that the KR truly coveted from Cambodia’s history and that were to be appropriated as lightning conductors to channel the newfound, energetic sense of nationhood; it is for this reason that the temples did escape systematic destruction. In fusing national sentiment for the country’s monuments to its malformed doctrinal syncretism, the KR policymakers cunningly grounded their politics in history; the Regime praised the ability of Jayavarman VII to mobilize the masses with his enormous construction projects and, also somewhat paradoxically, eulogized the ancient king’s efforts to break with the past in introducing Mahāyāna Buddhism and, thus, a new “ideology.” Pol Pot would urge his country to look to these vast undertakings in his now infamous saying: “If our people could build Angkor Wat, they are capable of doing anything.”Footnote 115

There were two core components of the Khmer Empire that the Regime chose to venerate: naturally, the monumental complexes, but also the hydraulic systems inextricably linked with the temples of Angkor, which played a crucial role in the history of the empire. The leadership believed that the capture and control of hydraulic energy was the source of ancient Khmer power, while the temples were majestic illustrations of this strength. Incidentally, this was not a misplaced belief: the enormous reservoirs (baray) regulated the temperamental heavy and short monsoons by allowing the civilization to expertly control the available water throughout the seasons. To give an idea of the scale of these constructions, it is estimated that West Baray was the “largest single engineering project in the pre-industrial world.”Footnote 116 The latticework of canals, embankments, and strategic dams prevented flooding and generated hydraulic power that allowed for the construction of temples while providing year-round labor for the slave population.Footnote 117 In short, the hydraulic infrastructure, driven by the masses, was medieval Cambodia’s powerbase, while the magnificent temples were a by-product of this technical ingenuity. This is reflected in Pol Pot’s statement on the seventeenth anniversary of the Communist Party on 27 September 1977: “We take agriculture as the basic factor and the use of the fruits of agriculture to systematically build industry.”Footnote 118

Accordingly, the KR leadership was obsessed with all things hydraulic and duly presided over hundreds of water-based agricultural projects—there has not been a modern regime that has devoted more resources toward developing irrigation.Footnote 119 In attempting to emulate the Khmers’ hydraulic cities and networks by mimicking this water-based means of production, the leadership truly believed that these developments would become “a fundamental plank in their economic policy.”Footnote 120 The eleventh century rather than the 1960s was the model.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in two extraordinarily revealing pieces of evidence. The first comes in the form of a Cambodian 50 riel banknote printed in China (although never distributed to the wider population) that depicts the Bayon superimposed on a landscape scene of a flooded paddy field (see Figure 11). The connection between Angkor’s past and the present vision of a new hydraulic country was merged into an intentionally symbolic motif and presented on currency that, had it been issued, would have been seen by a large part of the Cambodian population. The second piece of evidence emerges from the multiple reports that sanctioned foreign visitors were taken around Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom together with some of the grand reservoirs and dams constructed during the Regime.Footnote 121 A section on tourism in an immensely important Democratic Kampuchea document on policy—Four Year Plan to Build Socialism in All Fields—talks about tourists visiting Angkor Wat, Angkor Thom, and Banteay Srey along with tours of the “system of dikes, irrigation channels, canals, ricefields, vegetable gardens, and fishing areas.”Footnote 122 Aside from veiling the untold sufferings of Cambodians, these premeditated tours clearly conflated Democratic Kampuchea’s new irrigation systems with the glories of Angkor and suggested that the temples were proof of the prosperity of these hydraulic techniques.

Figure 11. 50 riel banknote depicting the merged scene of what appears to be the famous four-faced towers of the Bayon and an idyllic agrarian scene of peasants planting rice fields (courtesy of the personal archive of Locard Reference Locard and Falser2015, 208).

How did the Regime transmit these beliefs to its own people? The proposed banknote was one way–although, of course, it never came to fruition–while others included the constant rhetoric of local apparatchiks Footnote 123 and oral transmission—songs paralleled the KR’s achievements with those of the Khmer EmpireFootnote 124—while Phnom Penh Radio emphasized the significance of irrigation to the workforce building these dams and canals.Footnote 125 One of the most obvious techniques was through the symbolism of the Cambodian national flag (see Figures 12 and 13). By adding the iconic towers of Angkor Wat to the flag of Democratic Kampuchea, the KR drew a pronounced association between their Communist Party and the Khmer Empire. Article 16 of the Democratic Kampuchea Constitution clarifies this idea: the red of the flag symbolizes the revolutionary movement, “the resolute and valiant struggle of the Kampuchean people for the liberation, defence, and construction of their country,” while the yellow represents “the national traditions of the Kampuchean people, who are defending and building the country to make it even more prosperous.”Footnote 126 Neither Karl Marx, nor Chairman Mao, nor even Pol Pot hung on Democratic Kampuchea walls: “[O]nly Angkor was considered safe enough to become the symbol for DK.”Footnote 127

Figure 12. Democratic Kampuchea’s national flag; a red background symbolizes the revolutionary movement and communist roots with the stylized, yellow, three-towered temple of Angkor Wat in the middle (Dy Reference Dy2007, 21).

Figure 13. A more realistic reality, the KR control Angkor, 1975Footnote 128

But perhaps one of the most fascinating, and insidious, ways the Regime took advantage of its Angkorian legacy was to take the reverential power of the temples and monuments and distort it into a means of authoritarian control. For under Democratic Kampuchea, Buddhism and “family-ism” (kruosaaniyum), or family life, were replaced with a devotional attitude to the Angka,Footnote 129 the highly secretive political organization that was the forerunner and heart of the KR prior to 1975: “It was the Angkar who saved your life, neither God nor genii.”Footnote 130 This renunciation of societal traditions in favor of a quasi-religious political body took precedence over everything; the French missionary and genocide historian François Ponchaud has observed that on the Phnom Penh radio, the Angka was spoken of in highly reverential tones; it was “loved,” it was “believed in,” and it was the source of all happiness and inspiration.Footnote 131 As one of the defining aphorisms about this amorphous, shadowy entity demanded, “[o]ne must trust completely in the Angka, because the Organisation has as many eyes as a pineapple and cannot make mistakes.”Footnote 132 This is taken to mean that the Angka knows everything that is happening; it can see in all directions, just like the eyes of a pineapple point in all directions. Crucially, this widespread metaphor for the Angka was designed to invoke the all-seeing eyes of the head God of the Bayon Temple with its four faces watching the four cardinal directions (see Figure 11).Footnote 133 The similarity in the image of the all-seeing eyes of the pineapple with the four-faced tower of the Bayon is uncanny, as the anthropologist John Marston has proposed: “[U]nconsciously or not, the Khmer Rouge metaphor of the pineapple recalls this icon.”Footnote 134 This has somewhat unerringly been confirmed by visitors to the Bayon who repeatedly describe the same feelings of a presence peering at them from no matter where they stand: “Wherever you turn at least one pair of eyes follows you. The faces representing the all-knowing, all-seeing god King as he keeps watch over his subjects.”Footnote 135 In effect, the Regime had manufactured a culturally resonant metaphor that harnessed the architectural power of the Bayon into something that could be deployed as an ominous form of social conditioning. Indeed, the Bayon’s presence on the 50 riel banknote does imply this foreboding, subliminal form of control. In Pol Pot’s Cambodia, the Angka was omniscient.

PRISONS AND INTERROGATION

The KR’s appetite for horror is perhaps best demonstrated in this article by the Regime’s use of holy temples as places of torture and imprisonment or “offices of internal security” (munty santebal).Footnote 136 Indeed, Cambodian monastery compounds often made good prisons since the structures had many doors but few windows, and “once the wooden doors were closed, no one could observe what was really happening inside them.”Footnote 137 Village smiths would install bars and rings (khnohs) to manacle the prisoners, and a hellish system was designed to quickly liquidate inmates: day and night, they were led into interrogation and torture chambers, then executed and buried. At Wat Sophy (also known as Ka Koh), a prison that was operated from 1973 up to the fall of Democratic Kampuchea in 1979, a former captive said he saw “prisoners chained in two rows, with each row composed of 20 to 30 prisoners” being led to torture and eventual execution.Footnote 138 These murder systems were notoriously effective; it is estimated that over 5,000 people died at Wat Sophy, for example.Footnote 139 There were different forms of incarceration, not all designed for execution, as at Krol Ko, which doubled as a “re-education centre”: “As they led him away, a soldier was telling him, ‘Angkar is proud of you, Mit Bu, for your honesty and courage. … We are taking you to live at Wat Krol Ko to cure you of the brainwashing you suffered during the Lon Nol regime.’”Footnote 140

Ian Harris, industrious as ever, has meticulously detailed the specific wat sites that were employed as prison and torture centers.Footnote 141 Of the temples at Angkor, Banteay Samré was converted into a penal complex. The philosopher Mark Vernon, after visiting the temple, gives the following description of what happened here under the KR: “The holy galleries were divided into airless cells. Out of a temple was fashioned a hell hole: the day we visited, it was 40 degrees in the shade. People were bricked into this prison and forgotten. Before the monument could be reopened to the public, mounds of human bones had to be cleared from its enclosures and cells.”Footnote 142 Today, many temple compounds in Cambodia are still surrounded by charnel houses and mass graves that house the human remains from these execution centers, the bones that lie here afforded no dignity in death.Footnote 143 As a final thought on these macabre events, it should be noted that, while the KR’s sense of practicality demanded the irreligious use of temples, there was also an element of abhorrent symbolism: the nihilism of the Regime dictated that they should turn places of serenity, tradition, and culture into temples of hate, horror, and death.

NEGLECT

The destabilization of Cambodia in the 1970s brought about the suspension of important conservation work that subsequently left many monuments, both Angkorian and post-Angkorian, in a fragile condition.Footnote 144 This parlous state was all the more keenly felt because of the impressive progress made in conservation by French archaeologists during the 1960s; they had expanded and reinforced the internal coherency of the EFEO and, by extension, general Cambodian conservation practice. Under the direction of Bernard-Philippe Groslier, the chief conservator of the EFEO, this progressive drive culminated in the implementation of important intervention strategies, such as anastylosis in the AAP, which was used to reconstruct crumbling temples, remaining faithful to the original architectural layouts and, where possible, utilizing original material.Footnote 145

The KR nullified years of this painstaking French work. The research, conservation, and restoration program, which included photography, surveying, assiduous documentation, and reconstruction, was dismantled. Many heritage sites fell into structural ruin, and there was reclamation of temples by the jungle; the overall effect was one of regression. The historian David Snellgrove makes a lucid comparison here with Thailand and the success of its initiatives over the last 50 years in the rediscovery and presentation of early sites (including those of the KR); Cambodia, by contrast, “has neglected and then often destroyed the results of earlier French efforts at preservation.”Footnote 146 As it happens, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam offers an ideal conservation model for the Indochina region, commendable for its forward-thinking, legislative approach to the preservation of historic sites.Footnote 147

Our appraisal of the Cambodian conservational situation under the KR is not helped by the vacuum of information available for much of the 1970s. The country had become the subject of wild speculation after various missions and visits in 1981 (the United Nations Children’s Fund, a Polish International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) mission, and the Japanese expert Ishizawa Yoshiaki) reported both collapsing and undamaged temples that were heavily overgrown due to many years of neglect.Footnote 148 A National Geographic feature in 1982 sums up this ambiguousness and contradiction: “Despite rumours and exaggerated reports that the temples were demolished or severely damaged, we can report that, amazingly, they are nearly unscratched by the years of war” (see Figures 14 and 15).Footnote 149 That the temples were “unscratched” is clearly inaccurate, as we have seen. Nevertheless, the 1982 report is useful in that it highlights the deterioration of temples, which can, with retrospect, be attributed to the discontinuation of EFEO initiatives to protect the monuments from destructive vegetation.

Figure 14. “The Temples of Angkor: Will They Survive?” National Geographic, May 1982. The cover photo is possibly a face from the Bayon (reprinted in Falser 2015b, 239).

Figure 15. “The Temples of Angkor: Will They Survive?” National Geographic, May 1982. A two-page spread showing a Vietnamese guard in front of Angkor (reprinted in Falser 2015b, 239).

The Abandonment of Conservation

The intensification of the Civil War in the early part of the 1970s immediately displaced conservators at work in the AAP and, in particular, in Angkor Wat. The iconic temple was undergoing substantial restoration by an EFEO team—working on the removal of accumulated earth and vegetation and the dismantling of the temple’s outer southeastern gallery in anticipation of anastylosis—when the invasion of the North Vietnamese Army, together with several KR battalions, abruptly put an end to the work.Footnote 150 Caught in the middle of a Republican offensive on communist positions in January 1972 (the offensive discussed in the first section on conflict damage), Bernard-Philippe Groslier, overseeing the work, was expelled, and his Cambodian workers arrested: “20 were executed for ‘providing information to the Central Intelligence Agency.’”Footnote 151 The EFEO initiatives on approximately 50 temples in the region were terminated, and the laborers were either forced to leave or killed. The sites quickly fell into decay, and years of work faded away as Cambodia’s thick jungles overwhelmed the monuments.

After the establishment of the Regime, any conservational progress made during the 1960s was immediately lost. The military presence that dominated the AAP rendered archaeological sites inaccessible; conservators were forced to concentrate their energies on sites within, and to the south of, Siem Reap.Footnote 152 Worse still, Cambodian curators and conservators were subsumed under the intelligentsia that the KR did so much to neutralize; conservators were at best forbidden to work and at worst executed. The hostile treatment of the organizations and administrative buildings that were the core of Cambodian conservation also exacerbated matters—for example, the activities of the Angkor Conservation Office were significantly curtailed,Footnote 153 and one of the office’s compounds, just west of Angkor Wat, was converted by KR soldiers into a rice storage depot (as the Vietnamese also did in 1979), where “many of the [stored] sculptures were just pushed aside to make room.”Footnote 154

It seems that the Regime had no systematic policy apropos of the enormous quantities of archaeological material at their disposal. Angkor Wat’s principle sanctuary, the east gallery known for its bas-reliefs depicting the Churning of the Sea of Milk, attests to this neglect: the roof, columns, and lintels, dismantled for anastylosis, lay on the earthen terrace outside the structure awaiting reassembly.Footnote 155 This state of abandonment was propitious to natural forces: vegetation and especially fungi, lichen, and other cryptogamous organisms caused structural distress and discolored most parts of the monuments with “shrubs, vines, and trees covering parts of the [temple] and growing opportunistically along the upper edges of the terraces and roof surfaces.”Footnote 156 Elizabeth Becker, while visiting Angkor under the Regime, remarked that there was little major damage to the temples but a noticeable proliferation of undergrowth.Footnote 157 This mirrored much of the disinterestedness in conservation around the country; unless temples provided functional use, many (such as Wats Monisovan, Por, Enkosa, and Enkosey) were abandoned to the mercy of the elements.Footnote 158 In 1982, National Geographic was one of the first publications to lift the veil of secrecy on the fate of Angkor after years of speculation (see Figures 14 and 15); in an insightful article, Pich Keo, the conservator on site said simply: “In short, I have learned that the major problem at Angkor of late has been neither war damage nor thievery, but simply neglect.”Footnote 159

Even after the fall of the KR in 1979, the lingering presence of guerrillas acted as a deterrent to the conservation of temples in certain provinces. Adverse conditions, including KR strongholds, unexploded ordinance, and a devastated social and physical infrastructure, would disqualify any activity in the west and north of Cambodia until the beginning of the twenty-first century.Footnote 160 Conservation did take place, but it was limited; worthy of mention is the Archaeological Survey of India, which worked in extremely difficult conditions during its 1986–93 tenure at Angkor Wat, the prevailing war-like conditions at the time likened to an “atmosphere of deep insecurity.”Footnote 161 The dedication of the Indians in these circumstances is well attested: “[W]hen India was asked to conserve the great monument of Angkor Wat, it was a still a turbulent time, the scars of war were visible everywhere, materials were not available, quarries were infested with landmines.”Footnote 162

The persecution of skilled workers and intellectuals was, conceivably, the most severe blow to Cambodian conservation. The victimization was merciless; in 1975, around 750 workers of the Conservation d’Angkor were relocated to a camp in the town of Roluos where many were tortured and executed and others sent to work in the fields.Footnote 163 Of approximately 1,000 inhabitants of Siem Reap who oversaw and maintained the AAP, less than a dozen survived the KR years.Footnote 164 The death of these trained professionals, combined with the 20-year hiatus in conservation and maintenance, left Angkor dangerously understaffed and undermanaged. The resumption of work on heritage after years of war was further impeded by the erasure of conservation recordsFootnote 165 and the Heng Sarin government’s endemic corruption; under the Vietnamese, there was no coherent policy on the treatment of ruins and a severe shortage of funds required to pay for administrative services.Footnote 166 It took until 1984 to organize a committee concerned with the care of the Angkorian temples, and, even then, plans were continuously scuppered by budget constraints.

This disorganization and the scarcity of Cambodian intellectuals has led to the country’s “conservation void” being filled by foreign resources and expertise, creating difficulties with multilateral politics and internationally vested interests; in an implicit way, Angkor has essentially become a political pawn.Footnote 167 However, the resumption of work in the AAP, along with the recent political stability in Cambodia has, on the whole, been encouraging; there are now over twenty organizations and countries working in cooperation together at the center of a dynamic international conservational and archaeological effort. Much is to be applauded.

CONCLUSION

As is so often the case in war, what has taken years, even epochs, to create can be ruined by a single destructive act. Consequences are without remorse, and as we are continuously being reminded—most recently by the mindless barbarity in Syria—cultural destruction is often a handmaiden to armed conflict. There were no exceptions in Cambodia: at the mercy of aerial bombardment, internecine warfare, and a draconian imposition of communism, all of which plagued the country during the 1970s, the Angkorian temples, and to a far greater extent, the post-Angkorian wats and pagodas, succumbed to violence.

The destruction and damage was especially prevalent during the Civil War and the Vietnamese invasion for the simple reason that temples and wats, from the outset, were used as military fortifications. In 1975, the revolutionary accession of the KR over the Republican government precipitated the dissolution of traditional Cambodian religion and, with it, the security of Buddhist heritage. Cambodian temples, as foci of religious veneration, were ravaged: first, by the KR’s vendetta-like campaign against Buddhism and, second, by the Regime’s merciless sense of pragmatism. The Communist Party utilized the physical and metaphorical dimensions of these ancient structures in whatever way they could, whether as strategic military bases or bureaucratic offices. Angkor’s image was manipulated to suit their ideological vision of an agrarian utopia, and they promulgated a message of themselves as inheritors of the illustrious kingdom of the Khmers accordingly. Through the apparatuses of propaganda, there was a pervasive transmission of this fabricated historical legitimation, deployed for its supposed mobilizing effects on Cambodia’s populace at home and a chest-thumping sense of nationalism abroad. Thus, this ruthless, all-round program of exploitation amounted to the use of temples as multifunctional tools or resources that satisfied the Regime’s most pressing martial and governmental needs.

Such was Democratic Kampuchea’s venomous legacy, that even after the vanquishing of Pol Pot’s de-humanized automatons, the destruction of cultural property continued until late in the twentieth century, primarily through looting and the effects of guerrilla warfare. Although the warmongering during the 1970s has taken its toll, the real damage has become apparent in post-Democratic Kampuchea looting, facilitated by an almost anarchic Cambodia in the aftermath of the Regime. It is sadly ironic that Angkor, after surviving a decade of neglect, civil war, totalitarianism, and Vietnamese occupation, should fall victim to thieves who plundered statuary, lintels, and bas-reliefs to sell on the international black market.