Much of the most important and stable cooperation among states occurs through formal treaty making. International treaties are negotiated and signed by leaders but must be ratified domestically to have binding force. Notably, some treaties are signed and then ratified quickly while others languish, unratified by one or more parties. What explains this variation in the time between signature at the international level and ratification at the domestic level? Why are some treaties signed but never ratified at all? By exploring the fate of agreements after leaders bring them home, we shed light on a key stage of international cooperation that has received relatively little attention in the international relations literature.

Ratification is important from both a legal and a political perspective. As one law scholar notes, ratification implies consent and thus “transforms an international agreement from a piece of paper devoid of any legal force into law that binds.”Footnote 1 States are not legally bound by treaty commitments until they are ratified, and treaties do not enter into force until a sufficient number of states has done so.Footnote 2 The political implications of ratification are also profound. While a signed treaty may reflect the negotiating goals of a state's leadership, ratification roots the commitment in domestic institutions and strengthens sympathetic domestic groups, thereby enhancing its credibility.Footnote 3 Joint ratification is also a public demonstration that all sides expect the treaty to be enforced.Footnote 4 Given its distinct role, ratification merits analysis apart from the study of signature and of cooperation more generally.

Indeed, recent examples demonstrate that the ratification stage is important in practice. The Kyoto Protocol on climate change was signed by almost a hundred states after negotiations concluded in 1997, but ratifications were slow in coming and the treaty did not enter into force until 2005. After European governments signed the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, ratification problems in Denmark, France, and the United Kingdom imperiled and delayed its entry into force (and thus the establishment of the European Union). Economic agreements face similar obstacles. The administration of U.S. President George W. Bush negotiated and signed free trade agreements with Panama, Colombia, and South Korea, touting their economic and political benefits. Yet all three agreements lay dormant in Congress for years, with opposition from labor, environmental groups, and import-competing industries—and with no legal effect on these international trading relationships.

We explore the politics of ratification in the context of international investment agreements. Foreign direct investment (FDI) is governed by a vast tapestry of bilateral investment treaties (BITs), designed to ease barriers to foreign investment and guarantee legal rights for investing corporations. Governments have signed about 2,700 BITs since the late 1950s, and their popularity has accelerated over the past two decades; today almost every country in the world is part of this treaty network. The importance of BITs is underscored by the tremendous growth in FDI over the same period: from less than $100 billion in 1980, global inflows of FDI rose to $1.8 trillion by 2007, a result of the expanding activities of transnational corporations.Footnote 5 BITs are the primary vehicle for regulating this expansion.

While political scientists, economists, and legal scholars have focused considerable attention on BITs in recent years,Footnote 6 existing studies focus on why states pursue BITs, why they are designed in certain ways, and what effects they have on investment flows. We add to this growing literature by exploring the politics of BIT ratification. Specifically, we ask why some BITs are signed and then ratified promptly while others take years to ratify or never enter into force at all. Variation in this regard is substantial. About half of BITs are mutually ratified relatively quickly—within two years of the signing date. Others face more substantial obstacles. According to an inventory by the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), at the end of 2005 a quarter of signed BITs had not entered into force, leaving more than 600 agreements in limbo at the domestic level in one or both countries.Footnote 7 Some countries seem noticeably more susceptible to ratification failures. All fifteen of Japan's signed BITs and fifty-six of Hungary's fifty-eight have been mutually ratified; on the other hand, more than one-third of Russia's seventy-one BITs have not entered into force. In an extreme case, Brazil signed fourteen BITs, all in the mid and late 1990s, but has ratified none for a variety of political reasons.Footnote 8

This variation raises interesting political questions and also has economic and policy implications given that signed BITs have less impact on FDI flows than BITs in forceFootnote 9 and because governments are often reluctant to pursue BITs with partners they believe might not ratify.Footnote 10 The added credibility from ratification explains why some capital-exporting states require the existence of a BIT in force as a condition for protection under national investment insurance schemes.Footnote 11 Moreover, the investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms established in almost all BITs, an increasingly popular and valuable tool for companies seeking redress from host governments,Footnote 12 can be implemented only in the case of mutual ratification.Footnote 13 In short, ratification matters in the context of investment treaties.

Because ratification is ultimately a domestic process, we turn first to the theoretical literature on domestic institutions and “two-level games” for insights on time to ratification. We generate and test hypotheses related to the formal requirements of treaty ratification, usually involving a legislature, and the broader political constraints facing national executives. We also consider the ability of executives to rationally anticipate obstacles to ratification, both at home and in the partner country, based on the logic that leaders may never sign a treaty—or even initiate negotiations—if they believe ratification is unlikely. We hypothesize that failure to anticipate obstacles is most likely to occur when political systems are unpredictable and when governments have difficulty discerning obstacles in the partner. Finally, we consider characteristics of the dyadic relationship that might enhance political obstacles or reduce predictability between signatories. We make use of numerous interviews with private and government actors involved in BIT policy to guide our theoretical development. We test our hypotheses with data on the time between signature and entry into force for more than 2,500 BITs, using event history analysis as the most appropriate technique for capturing the probability that an event will occur after a given period of time.

The next section reviews the literature for insights on the politics of treaty ratification. We then present our hypotheses. A section on research design introduces the data, variables, and estimation techniques, and then a discussion of our results follows. The penultimate section outlines implications for our understanding of BITs and treaty ratification more generally. We offer broader theoretical lessons and suggest a research agenda—at the intersection of international relations and law—on the politics of international treaty making. A brief summary of our main arguments and findings concludes.

Ratification in the Literature

Treaties are written agreements among states by which they assume legal obligations.Footnote 14 Treaties are first negotiated at the international level, then signed by leaders, and then ratified through a procedure that roots the obligations in domestic law.Footnote 15 While political systems vary widely in their ratification requirements,Footnote 16 in almost all cases ratification imposes a significant hurdle. Indeed, it is the added complication and cost entailed in ratification that distinguishes treaties from other forms of international agreement.Footnote 17

The most common argument for why states use formal legal agreements is that they require a mechanism to credibly commit—for example, to democratic reform, to human rights, to liberal economic policies, and to the protection of foreign investors.Footnote 18 It is doubtful whether legal obligations can serve a commitment function if they are not ratified. Signatures and other public expressions may help signal a leader's intentions but such signals are not necessarily reassuring to other governments and private actors. After all, a government's preferences may change over time as domestic pressures evolve and as the leadership itself turns over, and signed agreements may never be implemented if domestic actors do not formally assent to them. In contrast, institutionalized concurrence at the domestic level enhances credibility and policy stability.Footnote 19 Partly for these reasons, in quantitative studies ratification is increasingly preferred to signature as a more meaningful indicator of participation in a regime.Footnote 20

Nevertheless, international relations scholars have not taken the critical role of ratification in interstate cooperation seriously enough and it remains poorly understood. This is true despite an interest in the specific stages of international cooperationFootnote 21 and in analyzing international legal institutions from a political perspective.Footnote 22 The lack of empirical and theoretical focus on ratification is especially puzzling given calls among political scientists and law scholars alike to examine more carefully the relationship between domestic politics and international cooperation.Footnote 23 We know with confidence that domestic politics matter for international cooperation but have neglected a central nexus between these domains.

The two-level games literature recognizes explicitly that international agreements must be acceptable to key political actors back at home.Footnote 24 Some work in this vein refers specifically to the role of ratification, though it is usually treated as unproblematic—following directly from signature—or as an exogenous constraint that influences cooperation. A number of scholars are interested in the effect of anticipated ratification hurdles on bargaining outcomes, in terms of both the content of agreements and the likelihood of successfully reaching agreement.Footnote 25 There is also substantial interest in the effect of treaties—as a formal and public commitment—on state behavior, especially compliance.Footnote 26 Those who do seek to explain ratification as a distinct outcome generally do not distinguish between the signature and ratification stages.Footnote 27

All of these works take domestic politics seriously but leave many questions about ratification unanswered. We build from their insights on the relationship between domestic institutions and international cooperation to generate testable hypotheses of both a monadic nature (political features that make an individual country less likely to ratify) and a dyadic nature (features of a relationship between two countries that complicate ratification).

The Politics of Ratification: Hypotheses

To build our theoretical propositions, we look first to domestic institutional constraints on the executive. In most countries there are constitutional or other formal requirements for achieving treaty ratification, usually involving the legislature. Evidence from the European Union (EU) and international trade agreements shows that variation in these procedures has an important influence on ratification outcomes.Footnote 28 While the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty was generally popular in the United States, after President Bill Clinton signed it in 1996 he was unable to find the sixty-seven votes necessary in the Republican-controlled Senate to achieve ratification.Footnote 29 Thus the formal process of treaty ratification is important to consider. In some countries, no legislative approval is required. When approval is required, some executives must achieve assent from only one house of the legislature while others must achieve it from two. For example, a recent report notes that a BIT signed between Belgium-Luxemburg and Colombia is unlikely to be ratified by the former due to opposition from trade unions and the complex ratification process, which requires the support of “two Federal chambers of parliament, as well as three separate regional governments.”Footnote 30 The voting threshold also varies across countries, with some legislatures approving by a simple majority and others requiring variations of a supermajority. As these hurdles become more difficult to overcome, we expect ratification to be increasingly difficult, other things being equal.

H1: The more significant the formal ratification requirements faced by an executive, the more difficult ratification is to achieve.

Of course, leaders face many political obstacles that are not captured in the formal process of treaty ratification, and it is important to consider such constraints in addition to the specific hurdles governing treaty ratification. As one U.S. BIT negotiator explained, it is not just the ratification institutions that Washington takes into account in a partner, “it's how freely the government functions.”Footnote 31 Like legislation and other policy initiatives, treaty ratification entails issue-linkage at the domestic level and often requires the expenditure of finite political capital, thus the executive must take into account these broader political dynamics when advocating for a treaty. For example, President Barack Obama's efforts in 2010 to secure Senate ratification of the New START arms-control treaty with Russia were held up by Senate Republicans as part of a broad political strategy, not for reasons related to national security. Partly for these reasons, and because executives may depend on legislatures and local governments to implement a treaty's provisions, the preferences of other domestic actors matter even when they do not play a formal role in ratification. Thus the Canadian prime minister often seeks to “build a broad base of support for international treaties”Footnote 32—even though no such legal requirement exists.

Political systems vary from those where the executive has the freest hand to those where the executive's power is most in check—a function of the number of actors whose agreements is needed for policy change and other institutional constraints on decision making.Footnote 33 The existence of constraints reduces the size of the domestic win-set and makes it more difficult to overcome blocking coalitions.Footnote 34 The role of these “veto players” takes on additional importance when they have different preferences from the executive, as in the case of divided government.Footnote 35 The implication is that executives who are relatively unconstrained politically and institutionally should be able to achieve ratification more quickly and with a higher probability overall. Our second hypothesis goes beyond formal ratification requirements to capture this wider range of political constraints.

H2: The more politically constrained the executive at the domestic level, the more difficult ratification is to achieve.

The impact of institutions and veto players on ratification depends in part on the ability of leaders to anticipate the obstacles they pose. A second set of hypotheses captures this consideration. Rational leaders might not sign a treaty or invest in negotiations in the first place if they sense ratification problems, either at home or abroad. This logic applies to international cooperation generally: leaders have an incentive to discern and anticipate domestic obstacles to international agreements—at both the ratification and implementation stages—and to take them into account during negotiations.Footnote 36 As one study of the Amsterdam Treaty points out, most EU governments “engaged in extensive domestic consultations to minimize the possibility of subsequent ratification difficulties.”Footnote 37

On the other hand, the fact that we see many cases of ratification difficulty following signature indicates that these domestic obstacles are sometimes difficult to anticipate. Indeed, when partners fail to ratify BITs, this usually comes as a surprise to negotiators.Footnote 38 Following this logic, some scholars propose that ratification failure occurs when the executive faces high levels of uncertainty regarding the preferences of other domestic actors, especially legislatures.Footnote 39 Such uncertainty is likely to result from political systems that lack transparency or where institutions are unstable and therefore produce unpredictable outcomes. Commenting on Russia's unwillingness to ratify its BIT with the United States, one State Department official complained about “unspecified concerns” in the Duma that were “impossible to anticipate.”Footnote 40

H3: The more open and predictable the political system, the easier ratification is to achieve.

Governments also vary in their ability to investigate and detect ratification obstacles. While most governments have a sense of the obstacles to ratification they face at home, there is considerable variation in their ability to anticipate domestic roadblocks in the partner. Effective anticipation requires a sufficient level of government capacity and expertise, qualities that are possessed unevenly across countries.Footnote 41 Variation in capacity has been shown to matter in practice. For example, a lack of legal and institutional capacity has a negative impact on the ability of developing countries to participate effectively in trade negotiations and the World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute settlement mechanism.Footnote 42 In the realm of investment, one of UNCTAD's main concerns is to provide technical assistance and capacity building to developing-country policymakers interested in pursuing international agreements, including BITs.Footnote 43

We expect that governments that are preoccupied with more basic tasks, such as finding potential partners and learning technical details, have fewer resources to devote to investigating potential political obstacles to ratification in the partner. Greater capacity, on the other hand, reduces the risk of signing BITs that face ratification difficulty.

H4: The greater the government capacity, the easier ratification is to achieve.

Finally, there are characteristics of a dyadic relationship that could enhance or diminish political obstacles to ratification or that could affect the level of mutual predictability. Others have pointed to social and historical affinities that reduce the “cultural distance” and enhance mutual understanding between two countries, making them more likely to pursue agreements.Footnote 44 More generally, misunderstandings and miscommunication tend to occur when negotiations take place across cultures.Footnote 45 Executives are therefore more likely to misinterpret the actions and policy positions of domestic actors in partner states that are more culturally distant, creating space for unanticipated obstacles. For their part, domestic actors are less likely than executives to possess high-quality information on specific policy issues and partner characteristics, and are therefore partly dependent on broader cultural and political cues to make their assessments. They will view a given agreement more favorably when there is a closer relationship overall.

H5: Greater cultural and political affinity in a pair of states makes ratification easier to achieve.

Research Design

BITs offer an appealing laboratory for examining treaty ratification. Because they are bilateral, they allow us to bracket a variety of complicated strategic considerations that influence the ratification of multilateral treaties and that might be idiosyncratic in any given case. Multilateral treaties are further complicated because states can “accede” to them without ever signing them, whereas bilateral treaties are always signed and then ratified by the same parties that engaged in negotiations. In any case, the vast majority of treaties are bilateral, making BITs representative in this respect. Because they are relatively uniform in their structure and basic provisions,Footnote 46 BITs also have the advantage of allowing us to compare ratification experiences while largely controlling for variation in treaty design.Footnote 47 There is no other issue area with such wide variation across countries but with a similar degree of uniformity across treaties.

We use event history modeling techniques to estimate the effect of the independent variables on the duration of signed treaties before they enter into force. This type of analysis estimates the “risk” that an event will take place as time elapses. As such, it is especially suitable to account for variation in the timing of events.Footnote 48 The unit of analysis is the treaty and our data set includes 2,595 BITs from 1959, the year in which the first BIT was signed, to 2007. These treaties involve 176 states as parties, giving us a diverse and representative sample and a wide range of values on our independent variables.Footnote 49 We employ a Cox nonproportional hazard model with robust standard errors.Footnote 50 One advantage of this method is that it accounts for those BITs which are not in force by the end of the time period of the analysis (that is, data that are “right censored”).

The dependent variable—labeled time force—is the “spell,” or the number of months passed, from signing to entry into force (that is, mutual ratification). To code this variable we used UNCTAD data on the dates of entry into force of all BITs. This variable ranges from 0 for treaties that were signed and entered into force in the same month to 568 for the France-Chad BIT that was signed in 1960 and had not entered into force by 2007. Two thousand and thirty BITs, close to 80 percent of the total sample, entered into force in or before 2007.Footnote 51Figure 1 shows this variable's distribution with a histogram of ratification spells, grouped by the status of the treaties as of 2007. It indicates that most BITs in force were ratified rather quickly: more than 90 percent entered into force within five years. Interestingly, treaties not in force by 2007 are much more evenly distributed. Only 40 percent are within five years of signature and about 80 percent are within ten years. On the whole, this variable exhibits a great deal of variation.

FIGURE 1. Distribution of ratification spell by BIT status

One potential concern is that of selection bias. It is possible that some of the factors that lead a government to be eager (or reluctant) to sign a treaty are the same ones that lead to speedy (or delayed) ratification at the domestic level. This concern has rightly occupied those who study compliance as their dependent variable, where the concern is that a decision to change behavior in conformity with rules precedes the commitment and is not independently caused by it.Footnote 52 Selection is less of a concern for us, however, because we are concerned with only cases where signature has taken place, we must select on signed treaties, because the puzzle for us is the subsequent process of ratification. We also have reasons to believe that most of the economic and political factors that influence the selection of BIT partners manifest themselves before negotiations have even begun and thus should not have a systematic effect on the time between signature and ratification.Footnote 53

Nevertheless, we employ two strategies to address possible concerns with selection. First, we control for many of the variables offered in the literature to explain why states sign BITs, with an eye toward those that might plausibly have an impact on ratification as well. This allows us to assess our hypotheses independent of the factors that lead to signature. Second, we realize that there may be unobservable factors at play, such as tactics used by negotiators to address the concerns of domestic interests. As a further robustness check, we therefore ran a selection model designed for duration analysisFootnote 54 that simultaneously accounts for BIT signing and entry into force. The results from this model are largely consistent with proportional hazard models that do not account for selection effects.Footnote 55 This gives us further confidence that selection issues are not biasing our results.

Independent Variables

All the independent variables are coded for the year in which the BIT was signed. Summary statistics are reported in the appendix.Footnote 56 The first three variables capture domestic institutional constraints in the BIT parties and are designed to test H1 and H2. To capture the formal legal hurdles to ratification, we rely on information provided by Hathaway,Footnote 57 who looks at the constitutional requirements for treaty ratification for most countries in the world (we have filled in values for the countries included in our analysis but not in hers). We have coded each country according to the following scheme: 0 if no legislative approval is required, exemplified by Antigua-Barbuda and Israel; 1 if a simple majority in one house is required, exemplified by Armenia and Greece; 2 if a simple majority in two houses is required, exemplified by Argentina and Malaysia; and 3 if a supermajority in one or two houses is required, exemplified by Algeria, Burundi, and the United States.Footnote 58 This scheme is designed to capture the increased difficulty of ratification as the values get higher. Because each observation involves a pair of countries, we make the “weakest link” assumption—we expect that the party that faces greater legislative hurdles determines the timing of entry into force.Footnote 59 Thus the variable legislative hurdles reflects the maximum value of this indicator for each dyad.

Broader political checks on the executive are measured with two variables that capture the number and preferences of domestic players who have the power to veto policy change. First, we use Henisz's political constraints variable, which captures the number of domestic veto players and ranges from 0 to 1.Footnote 60 As values on this variable increase, the legislature, judiciary, and subfederal entities have greater control and executive discretion is diminished.Footnote 61 Second, we employ a measure of checks and balances from the World Bank's Database on Political Institutions (DPI).Footnote 62 This variable, labeled checks dpi, takes into account the type of the political system, the number of political parties, and the strength of the opposition. As with legislative hurdles, we assume that the executive who faces more domestic political constraints will determine the timing of entry into force.

The next three variables gauge how open and predictable a country's political system is, allowing us to test the logic behind H3. A sizable literature links democratic institutions and practices to political transparency. Because they require some degree of deliberation and accountability, democracies tend to supply more information about the positions and policies of elected leaders.Footnote 63 As democratic peace theorists have pointed out, the policymaking process in democracies is relatively open and slow, thanks to institutional structures and a free press, allowing partners to make more confident estimates of their preferences and likely behavior.Footnote 64 Recent studies find a strong positive relationship between democracy and transparency.Footnote 65 We measure this variable with the widely used Polity IV data set.Footnote 66democracy, which represents the lowest Polity score in the dyad, and ranges from −10 for a complete autocracy to 10 for a mature democracy.

Another key element of predictability involves the stability of political institutions and the society's respect for authority and the rule of law, which reduce the uncertainty involved in the policymaking process and narrow the range of likely political outcomes. We capture this with the variable law and order, which is a component of the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) index. It is designed to measure the “strength and impartiality of the legal system” and “popular observance of the law,”Footnote 67 and has been used by others to capture the strength of political institutions and the orderly nature of a political system.Footnote 68 It ranges from 0 for countries with weak legal systems that are routinely ignored to 6 for countries with powerful and impartial legal systems that benefit from high popular observance. We use the value for the country with the lower score on this variable.

Finally, past behavior could be a good indicator of the prospects for treaty ratification. A track record of achieving ratification reduces uncertainty over the ratification process in the eyes of both governments involved. We capture this possibility with the variable ratification ratio. This is the percentage of signed BITs that had entered into force by the year prior to the signing of the observed BIT. For example, the value for the 2002 BIT between Switzerland and Mozambique is the percentage of BITs in force by 2001 of the country with the lower ratio (in this case Mozambique, which had five out of thirteen BITs in force, a ratification ratio of 0.38). This variable ranges from 0 to 1, and we expect higher values to be associated with a shorter ratification spell.

Based on H4, we expect governments with capacity constraints to face greater difficulty in the ratification process because they have more trouble anticipating and addressing ratification obstacles (possibly at home but especially abroad) during the negotiation phase. We use two variables to test this hypothesis. Most broadly, larger economies have more physical and human resources at their disposal. This facilitates the collection of information on the prospects of ratification as well as the promotion of the process itself. We gauge such capabilities with the gdp, which is the natural logarithm of the smaller economy's gross domestic product. The second variable considers the means available to the government more directly by looking at its size relative to the entire economy. Thus, government expenditure is spending as a percentage of GDP of the government with the lower value. Higher values reflect fewer capacity constraints and are expected to result in faster ratification. We use data from the Penn World Tables 7.0 for the first variable and from the World Development Indicators for the second variable.Footnote 69

To investigate H5, we turn to dyad-level variables. We use two measures of cultural affinity or distance, designed to capture the level of mutual understanding of each other's society and politics. Shared language reduces the risk that ratification will be postponed as a result of legal ambiguities and divergent interpretations. Thus common language is coded 1 if the two countries share a formal language, and 0 otherwise. A shared colonial heritage often results in similar legal and political cultures,Footnote 70 which in turn may foster mutual understanding and a lower perceived risk of cooperation.Footnote 71colonial ties is coded 1 if the BIT partners share a colonial heritage, and 0 otherwise. We use two additional variables to get at the closeness of bilateral political relations. We first consider the existence of a formal alliance between BIT partners. Arguably, such security ties encourage partners to conclude and ratify international treaties.Footnote 72 Next, we account for the partners' compatibility of interests with affinity un, which measures voting similarity in the UN General Assembly.Footnote 73

Additional Variables

We account for additional economic and political factors that are generally associated with a desire to consummate BITs. Doing so allows us to investigate our key explanatory variables while controlling for some factors that lead to signature, and it also allows us to investigate whether some factors matter at both the signature and ratification stages.

States with higher exposure to FDI may find investment treaties more valuable, and states that are home to multinational corporations involved in foreign investment may feel greater urgency to protect their assets abroad. We measure the degree of exposure with the home country's net FDI outflows as a proportion of GDP, a variable labeled home fdi/gdp. Similarly, host countries that attract more FDI are likely to face greater pressure from foreign investors and their governments to quickly ratify the treaty. We measure the degree of exposure with the host country's net FDI inflows as a proportion of GDP, a variable labeled host fdi/gdp. We use data from UNCTAD to code these two variables.Footnote 74 The balance of economic development between the two partners may also affect the speed of ratification. A large difference in GDP per capita reflects a relative abundance of skilled labor in the home country and is conventionally used as a proxy for the potential gains from vertical FDI.Footnote 75 Accordingly, we expect country pairs that have uneven levels of economic development to ratify their BIT more quickly. We account for this possibility with development gap, which is the natural log of the difference in the dyad's GDP per capita.

Our framework emphasizes political institutions but one might also expect the ideological orientation of the executive to affect its eagerness to pursue investment treaties and to push for BIT ratification. Some research associates right-wing parties with liberal economic policies and left-wing parties with protectionism and lower commitment to international economic cooperation.Footnote 76 On the other hand, a recent study shows that labor is the main beneficiary of foreign capital and that, in turn, left-wing parties tend to adopt more welcoming policies toward foreign investors than right-wing parties.Footnote 77 We evaluate these opposing predictions with the DPI data set, which codes the executive's party as right, center, or left.Footnote 78 The variable left in office is coded 1 if a left-wing party is in office in at least one country, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 79

Recent studies on multilateral treaties, especially in the area of human rights, indicate that the type of legal system might have implications for the domestic fate of a treaty. Specifically, these works argue that countries with a common law system offer better domestic legal protection and see less need for external guarantees, and are therefore less certain to ratify international agreements than countries with other legal traditions.Footnote 80 We control for this possibility with common law, a dichotomous variable that scores 1 if at least one party has a common law system (that is, one of British origin), and 0 otherwise.Footnote 81 Finally, the fall of the Berlin Wall reflects a systemic change that was accompanied by an increase in global FDI flows, the number of BITs, and the number of countries that joined the global economy. cold war, which scores 1 from 1959 to 1989, and 0 thereafter, accounts for this systemic shift.

Results and Discussion

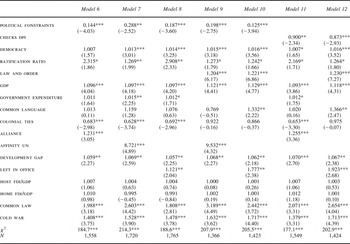

Tables 1 and 2 present the results of several event history models estimating the effect of the independent variables on the time that lapses between BIT signing and entry into force. The analysis includes a number of variables pertaining to domestic political institutions that are positively correlated and capture overlapping concepts. We therefore examine their effects separately. Table 1 reports five models that include legislative hurdles. Model 1 in this table serves as the baseline. Model 2 substitutes alliance with political affinity and Model 3 includes the executive's political party. The variable law and order has a limited temporal and spatial coverage, which leads to a significant reduction in the number of observations. It is therefore excluded from the baseline models but included in Models 4 and 5. Table 2 presents seven models that include the two political constraints variables. Models 6 to 10 include the variable political constraints but otherwise mirror the models in Table 1. Models 11 and 12 replace political constraints with checks dpi.

TABLE 1. Cox nonproportional hazard estimates—legislative hurdles

Notes: Figures in parentheses are z statistics. Numbers are hazard ratio: numbers > 1 indicate higher risk of termination; numbers < 1 indicate lower risk of termination. All models are tested for the proportional hazard assumption with the Schoenfeld test. Variables that violate the assumption are interacted with the logged function of time force.

* p < .1;

** p < .05;

*** p < .01 (two-tailed test).

TABLE 2. Cox nonproportional hazard estimates—executive constraints

Notes: Figures in parentheses are z statistics. Numbers are hazard ratio: numbers > 1 indicate higher risk of termination; numbers < 1 indicate lower risk of termination. All models are tested for the proportional hazard assumption with the Schoenfeld test. Variables that violate the assumption are interacted with the logged function of time force.

* p < .1;

** p < .05;

*** p < .01 (two-tailed test).

The tables report the hazard ratio, which estimates the hazard rates for different values on the independent variables. The hazard rate is the probability of the event (in our case, entry into force) occurring given its survival up until that point in time. In other words, the hazard ratio is the ratio of the hazard rate given a one-unit increase on an explanatory variable to the hazard rate without such an increase. A hazard ratio that is greater than 1 indicates a higher probability of entry into force, such that, as values of the independent variable increase, the likelihood of survival decreases. A hazard ratio lower than 1 represents a lower probability of entry into force.

In support of H1, we find that more onerous ratification requirements decrease the probability of entry into force. The hazard ratio for legislative hurdles is highly significant across all models and is substantively meaningful. Figure 2 illustrates this effect by plotting the estimated survival rate of unratified BITs at different scores on this variable. When it scores 0, indicating that legislative hurdles are minimal, almost all BITs are predicted to be in force within five years (or sixty months). When legislative hurdles scores 2, reflecting the need for a majority in both legislative bodies, only about half of the treaties are predicted to enter into force within five years. This result indicates that formal legislative hurdles—defined by the number of chambers and voting thresholds required—do indeed affect time to ratification.

FIGURE 2. Survival estimates at different scores of legislative hurdles

We find support for the effect of broader political constraints as well (H2). For all models in Table 2 they are highly statistically significant, indicating that higher executive constraints are associated with a longer ratification spell, whether we use the measure that includes the judiciary and subfederal entities (politicalconstraints) or the measure that offers a more nuanced account of the legislature (checks dpi). Figure 3 illustrates the substantive effect of political constraints by plotting the estimated survival rate of unratified BITs when this variable is one standard deviation below and above the mean. In the former, about 50 percent of signed treaties are expected to be in force within five years; in the latter, the rate decreases to about 25 percent. The substantive effect of checks dpi is more modest but still meaningful: more than 80 percent of signed treaties are expected to be in force within five years when the value of this variable is one standard deviation below the mean compared to about 65 percent when the value of this variable is one standard deviation above the mean.Footnote 82 Thus, political systems with more veto players and diverse preferences are slower to ratify investment treaties.

FIGURE 3. Survival estimates at different scores of political constraints

The three variables that capture the openness and predictability of the political system (H3) also fare rather well. The hazard ratio of democracy is larger than 1, indicating that higher levels of democracy are associated with shorter survival rates and thus speedier ratification. The estimate is statistically significant in most models but substantively modest: moving from one standard deviation below to one standard deviation above the mean increases the number of mutually ratified treaties within five years by about 8 percent. It appears that BITs involving highly democratic countries tend to enter into force more quickly but that this effect is not very pronounced. While democracy increases transparency and makes political constraints more visible, the effect may be dampened by the messiness of democratic politics, which often involves many competing institutions and interest groups that could present unanticipated obstacles to ratification.

Higher ratification rates in the past, another indicator of predictability, are associated with speedier ratification. ratification ratio is statistically significant in most models (although only weakly so in some cases) and has a meaningful substantive impact. When its value is one standard deviation below the mean, a little more than 50 percent of signed treaties are expected to be in force within five years; when its value is one standard deviation above the mean, the rate increases to about 65 percent. Apparently, when countries were quick to ratify in the past we can be more confident that they do not face unanticipated obstacles in the present. The effect of law and order is positive and highly significant in the models that include political constraints but negative and insignificant in the models that include legislative hurdles. Its substantive effect is modest in the models in which it is statistically significant. It thus provides only mixed support for our theoretical expectations.

Taken together, the three variables that capture the degree of transparency and predictability corroborate H3 and indicate that these features of a political system facilitate rational anticipation of domestic obstacles, making ratification easier once signature has taken place. The substantive effect of these variables is not as pronounced as those associated with the first two hypotheses, however. While governments systematically anticipate and take into account obstacles, they nevertheless face real constraints during the ratification process, implying that they face uncertainty (that the constraints were not anticipated) or that they sometimes choose to proceed even when ratification is in doubt.

The role of capacity as an important determinant of treaty ratification (H4) is substantiated by the results on the size of the economy and the government. The hazard ratio of gdp is always greater than 1 and highly significant. The substantive impact of this variable is meaningful: moving from one standard deviation below to one standard deviation above the mean increases the number of mutually ratified treaties within five years by about 15 percent. Similarly, government expenditure is always larger than 1 and is statistically significant in most models, though its substantive effect is very modest. In tandem, these variables suggest that greater capacity is conducive to more effective anticipation and thus speedier ratification, as H4 predicts.

Turning to the dyadic variables, we argue with H5 that political and cultural affinity between two countries has the effect of mitigating domestic obstacles and making them easier to discern. We find only modest support for the notion that common language speeds ratification by enhancing mutual understanding. As expected, the hazard rate is larger than 1 in most models but mostly falls short of statistical significance. In the models in which this variable is significant, the substantive effect is quite modest. Going against our expectations, the estimate of colonial ties is smaller than 1 and statistically significant in most models, indicating that the ratification of BITs between colonial siblings is slower than in other pairs of states. The substantive effect of this variable is very small, however. This surprising result parallels the findings of Elkins, Guzman, and Simmons on BIT signing. They speculate that states belonging to the same colonial family have similar political and legal institutions, and therefore these states do not find investment treaties indispensable.Footnote 83 The same logic may apply to the ratification process: countries that share a colonial heritage may conclude treaties for symbolic purposes but feel little pressure to ratify them. This is especially likely between developing countries that are seeking to fortify political ties by signing a BIT but that may not have high levels of mutual investment.

The results on bilateral political relationships are more consistent with theoretical expectations. Allies and pairs with common interests (as reflected in their voting patterns in the UN General Assembly) tend to ratify investment treaties much more quickly. The hazard ratios associated with these variables are always greater than 1 and highly statistically significant, and their substantive effect is meaningful. Moving from 0 to 1 on alliance increases the number of mutually ratified treaties within five years by about 8 percent. The substantive effect of affinity un is stronger in the first eighteen months following ratification but then gradually declines. It appears, then, that shared perspectives on foreign policy matters and security cooperation are conducive to lower uncertainty and diminished political obstacles—and thus to speedier treaty ratification. Overall, we find mixed support for H5: political affinity speeds ratification but cultural affinity has more limited effects.

The control variables give us additional insight into the dynamics of BIT ratification. Higher levels of FDI flows into the host country or out of the home country appear to have little effect on mutual ratification. It is likely that they affect behavior during the negotiation stage—especially in the choosing of partners—and are less consequential for ratification. We do find support for the effect of differences in development levels. development gap is larger than one and statistically significant in all models. The substantive effect of this variable is rather modest but nevertheless points to an economic rationale (or perhaps to a component of pressure or dependence) in the ratification process.

We find, notably, that left-wing governments ratify BITs more quickly than other types of governments. left in office is always statistically significant, highly so in some models, and its substantive effect is meaningful. When at least one government in the dyad is left-wing, about 85 percent of BITs are predicted to enter into force within five years. If neither government is left-wing the ratification rate within five years falls to 60 percent. This result provides initial support for the view that labor and the left are the main beneficiaries of FDI and will promote policies to attract capital into their economy.Footnote 84 Alternatively, it may be that left-leaning governments have a ratification advantage precisely because they are more hesitant and selective when it comes to signing BITs. Because they are normally skeptical of free-flowing capital, they send a strong signal to domestic actors that a signed investment agreement is sensible policy and in the national interest.

The results regarding the effect of legal heritage—captured in the common law variable—defy our theoretical expectations and other recent studies.Footnote 85 We find that countries with a common law system are faster, rather than slower, to ratify investment treaties. This effect is statistically and substantively strong, especially in the first two years following BIT signing. The decelerating effect of common law emerges from the study of multilateral treaties (which governments can ratify without signing) or the study of BIT signing (rather than ratification). Perhaps common law countries are more reluctant to sign international treaties, but once they sign they are more likely to enact them into law. While our results are only suggestive, they hint that the effect of common law on international agreements is more complex than was initially thought and add further weight to our premise that ratification should be treated as a distinct stage of cooperation.

Finally, cold war is larger than 1, statistically significant, and substantively meaningful. BITs concluded in the post–Cold War era take longer to enter into force. One potential explanation for this result is that many more treaties have been concluded in the past two decades, increasing the number and heterogeneity of both investment treaties and countries that sign them.

Overall, we find substantial empirical support for our hypotheses on ratification. Though countless factors may influence the fate of any given treaty, durable features of political systems and dyadic relations matter systematically across BITs. As we expected, formal legal hurdles to ratification and broader political constraints on the executive have an important impact on ratification (H1 and H2). Our proposition that some executives and dyads are in a better position to anticipate ratification obstacles also receives empirical support. More open and predictable political systems—those associated with democracy, stable political institutions, and a good track record of ratification—are able to ratify treaties more quickly, as H3 suggests, and governments with higher capacity ratify BITs more quickly, as H4 suggests. Finally, consistent with H5, countries that share a common language and especially those with close political ties are better able to consummate their treaties. These findings are robust to various model specifications and when we control for selection into treaties.

Treaty Politics: BITs and Beyond

Implications for BITs

Our study of BIT ratification demonstrates that politically interesting dynamics are at play between treaty signature at the international level and ratification at the domestic level. Notable implications arise when we combine these findings with what we know about BITs more generally. In some cases, there seem to be mutually reinforcing factors that lead to investment, to the signing of investment agreements, and to their ratification. Political and cultural affinity, for example, increases investment flows and the propensity of dyads to sign BITsFootnote 86 and also speeds ratification. Strong legal and political institutions attract investment and BIT partnersFootnote 87 and also facilitate ratification by rendering political systems more predictable and transparent. For these variables, the effect throughout the treaty-making process is in the direction of more exchange and cooperation, though somewhat different causal mechanisms are at play in each stage.

Other factors work quite differently across stages—they may be conducive to signing but not to ratification, or vice versa. The effect of domestic institutions illustrates this point. Common law countries are less attracted to BITs but ratify them more quickly once they are signed, and democracies are not more attractive as BIT partners even though they are more reliable ratifiers.Footnote 88 While weak checks and balances at the domestic level has been a major motivation for seeking credible commitment through BITs,Footnote 89 the same constraints have the effect of slowing ratification once the treaty is brought home. Historically, the end of the Cold War increased the rate of BIT signing but has slowed their average time to ratification.

Understanding that signature and ratification result from different processes helps explain why they seem to have distinct effects as well. Consider the notoriously complicated relationship between investment agreements and investment flows. Increasing evidence shows that, while signed BITs have little or no effect on FDI, BITs in force do indeed have the intended positive effect.Footnote 90 The United States-Russia BIT, signed in 1992, provides an illustration. From the perspective of the Russian leadership, the treaty was necessary to attract much-needed foreign investment into the country. However, while the U.S. Senate quickly ratified, it bogged down in the Russian Duma, where competing economic interests battled for control and where the oil lobby in particular opposed opening the door to foreign ventures.Footnote 91 This uncertainty contributed to a lack of confidence in the Russian investment environment and a markedly sluggish flow of American investment into Russia.Footnote 92 More than twenty years later, Russia has yet to ratify its BIT with the United States.

Beyond their effect on investments, ratified BITs have important political and legal consequences. The binding investor-state dispute settlement mechanism found in almost all BITs has proven to be highly consequential, leaving many hosts concerned about the political and economic costs of arbitration.Footnote 93 This has spurred a trend toward withdrawal from and renegotiation of existing BITs, sometimes with provisions designed to be less investor friendly.Footnote 94 As BITs become more politically controversial, especially in the developing world, we could see longer ratification delays in the future.

All of this suggests that those interested in the politics, economics, and law of BITs should make an analytical distinction between signature and ratification, a lesson that applies to treaties more generally.

Research on Treaty Ratification

Our analysis has implications far beyond the realm of BITs and suggests a broader research agenda—at the intersection of international relations and international law—on treaty ratification. We point to a number of politically interesting factors that might affect ratification but which our study, with its emphasis on country and dyad characteristics and bilateralism, is not designed to address.

First, variation across treaties could help explain their fate at the ratification stage. More complex agreements that implicate many domestic interest groups, “deeper” ones that require substantial change from the status quo, and more rigid and binding agreements are likely to slow the treaty-making process and face greater resistance at the ratification stage.Footnote 95 This suggests further analysis to look across agreements that vary in their design and ambition, connecting our concern with ratification outcomes to the growing literature on treaty design and legalization.Footnote 96

Second, ratification behavior no doubt varies across issue-areas. International obligations that have a concentrated impact on organized interests, as in trade, are more likely to attract resistance.Footnote 97 Politically salient issues such as climate change may also draw the attention of mass publics, who in turn pressure governments to ratify (or not).Footnote 98 Some treaties cover issues of normative importance, compelling governments to ratify as a result of international pressure or a sense that it is the right thing to do.Footnote 99

Third, multilateral treaties entail distinct ratification dynamics. For example, leaders might sign a multilateral treaty with no intention of pursuing ratification if they believe other states will do the same; they can get “credit” for signing but avoid blame for preventing its entry into force. Also, leaders might delay ratification in order to build coalitions of holdouts that have bargaining leverage over early ratifiers, a dynamic evident in the climate change regime.Footnote 100 Finally, multilateral treaty making attracts more attention from nongovernmental organizations, who can shape negotiations and subsequently apply pressure on governments to sign and ratify.Footnote 101 The variables we emphasize should still matter in a multilateral context but they are joined by a host of additional factors that could be developed into hypotheses for future research.

Fourth, governments have a variety of motives when they sign treaties and may value negotiations and signature on their own. Treaty making could be used to strengthen intergovernmental political ties and build confidence through negotiations, even if a binding agreement does not result. Alternatively, the pursuit and signing of an agreement may allow a government to signal to domestic constituencies that it is actively pursuing their interests, providing a political benefit even if ratification is not achieved. Leaders also could use treaty signing as a way to shift the domestic debate. A signed treaty becomes a focal point around which the leadership can mobilize support and weaken opposition.Footnote 102 Indeed, an important motivation behind Brazil's many unratified BITs was to shift the domestic debate in a more pro-investment direction.Footnote 103 Under these various circumstances, pursuing a signed agreement might be worthwhile even if ratification—with its additional benefits—is out of reach.

Finally, it should be noted that leaders might simply avoid ratification by choosing other forms of cooperation. When governments anticipate domestic obstacles or when they face uncertainty over such obstacles, they have an incentive to seek soft-law or executive agreements that do not require formal approval. Indeed, the primary appeal of such informal agreements is that they do not require a public and complicated ratification process and can be concluded more quickly.Footnote 104 This raises the question of why governments ever manage their cooperation through formal treaties. The answer lies precisely in the compensating virtues of ratification: it allows a government to both signal its cooperative intentions (because of the costly process of achieving ratification)Footnote 105 and credibly commit to cooperation (because of the costs of reneging on a legalized commitment).Footnote 106

Conclusion

The international politics and international law literatures have not taken the critical role of ratification seriously enough, and it remains poorly understood despite the central and growing role of treaties as a vehicle for structuring international cooperation.Footnote 107 We explore the politics of ratification in the context of bilateral investment treaties, which continue to proliferate and are the primary means of regulating FDI. While some BITs are signed and then ratified quickly by both sides, others take years to be ratified or never enter into force at all.

Using duration analysis, we find that ratification outcomes vary systematically as a function of political and legal constraints on the executive: greater constraints hinder ratification. However, when political systems are transparent and predictable, executives can rationally anticipate these obstacles, avoiding a situation where a signed treaty languishes either at home or abroad. This is especially true when executives have higher levels of capacity. Closer ties between BIT partners can also reduce uncertainty and opposition, thereby accelerating ratification.

This study has important limitations and considerable research remains to be done, both to provide more definitive tests of our hypotheses and to expand the purview to a wider range of treaties and issue areas. We see this work as part of a broader research agenda on the politics of treaties and as a vital contribution to the wave of interdisciplinary scholarship that combines the interests of international relations and international law scholars.Footnote 108

TABLE A1. Summary statistics