1. Introduction

Acoustic resonance is a common unsteady phenomenon in modern aero-engines and other turbomachineries, which can cause high-intensity noise and blade vibrations during operations and lead to decrease in fatigue life or even structural failures of the resonance cascade (Parker & Stoneman Reference Parker and Stoneman1989; Holzinger et al. Reference Holzinger, Wartzek, Schiffer, Leichtfuss and Nestle2015; Fiquet et al. Reference Fiquet, Aubert, Brandstetter, Buffaz and Vercoutter2021). The resonance phenomenon itself widely exists in wave motions, and is also termed trapped modes or trapped waves in water wave literature, and Rayleigh–Bloch modes in the electromagnetic research field (Duan Reference Duan2004). The essential of such phenomenon is that waves move in a globally non-propagating state (or being trapped) near some solid structures with a fairly small or even zero energy loss. Therefore, when acoustic resonance is excited by the complex flow structures in aero-engines, instability arises and the pressure oscillation will continuously grow until it reaches the limit governed by nonlinear processes. According to the mechanisms, acoustic resonances in aero-engines can be classified into two categories: one is caused by axial acoustic reflections (Woodley & Peake Reference Woodley and Peake1999a ,Reference Woodley and Peake b ; Cooper & Peake Reference Cooper and Peake2000; Cooper, Parry & Peake Reference Cooper, Parry and Peake2004) and always involves a cut-on acoustic duct mode; the other is related to the geometry of one single cascade, which can involve only cut-off acoustic duct modes. The latter is the main focus of this paper. Acoustic resonance modes can then be coupled to (Brandstetter, Paoletti & Ottavy Reference Brandstetter, Paoletti and Ottavy2019), or might even be one of the underlying causes of (as the authors suspect), some of the recently discovered instabilities in modern turbomachineries, e.g. the rotating instability phenomenon. These all limit the operating range of aero-engines and may lead to severe problems at off-design points.

In practical aero-engines or other cascade structures, dissipations due to viscous and other effects are inevitable; thus, the acoustic resonance modes must be excited by (or coupled to) an external source to trigger instabilities. However, the coupling to external sources will only slightly modify the frequencies of the pressure oscillations from those of the resonance modes (Parker & Stoneman Reference Parker and Stoneman1989). In addition, the imaginary part of the predicted characteristic frequency of the decoupled acoustic resonance system also serves as an indicator of the total energy dissipation, providing guidance to control methods based on acoustic designs, as in thermo-acoustic instability problems (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wang, Li and Sun2020). These all suggest that predictions based on a decoupled model are adequate in both theoretical investigations and practical engineering applications to control and prevent acoustic-resonance-related phenomena. Therefore, we use such a decoupled method to study the aeroacoustic properties of the resonance modes without any specific external source, as in many theoretical investigations on acoustic resonances (Parker Reference Parker1967; Koch Reference Koch1983, Reference Koch2009; Dai Reference Dai2024).

Towards resonance-induced failures in aero-engines, Parker and co-workers (Parker Reference Parker1966, Reference Parker1967, Reference Parker1968; Parker & Pryce Reference Parker and Pryce1974) conducted a series of pioneering studies on acoustic resonances in turbomachinery cascades. They first identified the classical single-cascade-resonance Parker modes in annular cascades and established a two-dimensional (2-D) analytical method to calculate the resonance frequencies for these stationary modes under zero-flow conditions. A lock-in mechanism between the vortex shedding at cascade trailing edges and the resonance modes is identified as the energy source for the resonance phenomena, which occur at constant Strouhal numbers. Koch (Reference Koch1983) later solved for the complex resonance frequencies of the Parker modes in 2-D flat-plate cascades in the presence of background mean flow using the Wiener–Hopf method, and briefly discussed the effect of stagger angle. Due to the symmetry of the stationary Parker modes, the geometry of an annular or plane cascade can be simplified as a blade inside a single tunnel to facilitate the investigation of the interactions between the trailing-edge vortex shedding and the acoustic resonance modes (Cumpsty & Whitehead Reference Cumpsty and Whitehead1971; Welsh, Stokes & Parker Reference Welsh, Stokes and Parker1984; Katasonov et al. Reference Katasonov, Sung and Bardakhanov2015). This allows detailed experiments into the frequency lock-in mechanism as well as theoretical descriptions of such a process. Hong et al. (Reference Hong, Wang, Jing and Sun2020) numerically studied this phenomenon using a 2-D discrete vortex method, and conducted further experiments (Hong et al. Reference Hong, Fu, Chen and Yang2023) into the basic

![]() $\beta$

resonance mode to which an acoustic suppression method is applied.

$\beta$

resonance mode to which an acoustic suppression method is applied.

Nevertheless, all the above-mentioned methods only predicted Parker’s stationary modes (four commonly seen modes named as

![]() $\alpha$

,

$\alpha$

,

![]() $\beta$

,

$\beta$

,

![]() $\gamma$

and

$\gamma$

and

![]() $\delta$

modes and the modes with higher axial orders, i.e. the modes with more axial nodes as discussed in Koch (Reference Koch1983)), which correspond to two specific inter-blade phase angles,

$\delta$

modes and the modes with higher axial orders, i.e. the modes with more axial nodes as discussed in Koch (Reference Koch1983)), which correspond to two specific inter-blade phase angles,

![]() $\pi$

and

$\pi$

and

![]() $2\pi$

. They did not capture other resonance modes with different circumferential periodicity (of different circumferential mode number). However, in most practical compressor cascade experiments (e.g. Parker Reference Parker1968; Parker & Pryce Reference Parker and Pryce1974; Camp Reference Camp1999; Holzinger et al. Reference Holzinger, Wartzek, Schiffer, Leichtfuss and Nestle2015), the observed resonances with high-pressure oscillation amplitudes are of spinning nature, and can be described using the fundamental rotating modes in duct acoustics (Tyler & Sofrin Reference Tyler and Sofrin1962) with circumferential mode numbers smaller than those of the Parker modes. The theoretical prediction for these practical resonances more or less lagged behind. Parker (Reference Parker1983) reported their complexity and only gave analytical lower and upper bounds for their resonance frequencies, corresponding to an infinitesimal-pitch cascade (compared with the circumferential wavelength) and the particular case of the original stationary Parker modes. This just provides a rough prediction of the resonance frequencies under the zero-mean-flow condition. Duan & McIver (Reference Duan and McIver2004) first gave a precise calculation method and a proof of the existence for such rotating resonance modes in a circular cascade without background mean flow, using the matched eigenfunction expansions method (Linton & McIver Reference Linton and McIver1998). Koch (Reference Koch2009) repeated their results using a numerical method by applying perfectly matched layers at the two duct ends. He further investigated the effects of blade stagger, blade number, blade sweep and tandem cascades, where he discovered that the cascade with the larger blade chord dominates the resonance frequency in a stationary tandem cascade with a moderate gap.

$2\pi$

. They did not capture other resonance modes with different circumferential periodicity (of different circumferential mode number). However, in most practical compressor cascade experiments (e.g. Parker Reference Parker1968; Parker & Pryce Reference Parker and Pryce1974; Camp Reference Camp1999; Holzinger et al. Reference Holzinger, Wartzek, Schiffer, Leichtfuss and Nestle2015), the observed resonances with high-pressure oscillation amplitudes are of spinning nature, and can be described using the fundamental rotating modes in duct acoustics (Tyler & Sofrin Reference Tyler and Sofrin1962) with circumferential mode numbers smaller than those of the Parker modes. The theoretical prediction for these practical resonances more or less lagged behind. Parker (Reference Parker1983) reported their complexity and only gave analytical lower and upper bounds for their resonance frequencies, corresponding to an infinitesimal-pitch cascade (compared with the circumferential wavelength) and the particular case of the original stationary Parker modes. This just provides a rough prediction of the resonance frequencies under the zero-mean-flow condition. Duan & McIver (Reference Duan and McIver2004) first gave a precise calculation method and a proof of the existence for such rotating resonance modes in a circular cascade without background mean flow, using the matched eigenfunction expansions method (Linton & McIver Reference Linton and McIver1998). Koch (Reference Koch2009) repeated their results using a numerical method by applying perfectly matched layers at the two duct ends. He further investigated the effects of blade stagger, blade number, blade sweep and tandem cascades, where he discovered that the cascade with the larger blade chord dominates the resonance frequency in a stationary tandem cascade with a moderate gap.

However, the above collected works on rotating resonance modes are all at zero mean flow conditions, which can only be treated as an approximation for slow-flow-speed scenarios (Koch Reference Koch1983). In practical aero-engines, however, the background mean flow Mach number is significantly higher, and the zero-mean-flow assumption is no longer applicable. Therefore, it is of great importance to develop a model capable of predicting the rotating resonance modes in the presence of non-zero background mean flow and to further investigate the corresponding resonance characteristics. Theoretically, Peake’s 2-D model (Woodley & Peake Reference Woodley and Peake1999a ,Reference Woodley and Peake b ) has the potential to estimate the rotating resonances in a 2-D cascade, yet they mainly focused on identifying the inherently unstable resonances between two cascades with zero dissipation and did not pay attention to other resonance modes. In real aero-engines, there exist complex unsteady flows and blade vibrations that may easily act as an external energy source to excite resonances, so a complete solution for all possible resonance modes with and without inherent dissipation is still necessary for practical engineering problems. In addition, three-dimensional (3-D) effects also play an important role in the acoustic prediction of annular cascades with moderately large hub-to-tip ratios. They have a great impact on the cut-off frequencies of the duct modes and thus the estimation of acoustic resonances in annular cascades. A fully 3-D prediction model is therefore necessary for practical cascades, especially for future studies on the effects of tip clearance, where the cascade is inherently non-uniform in the radial direction.

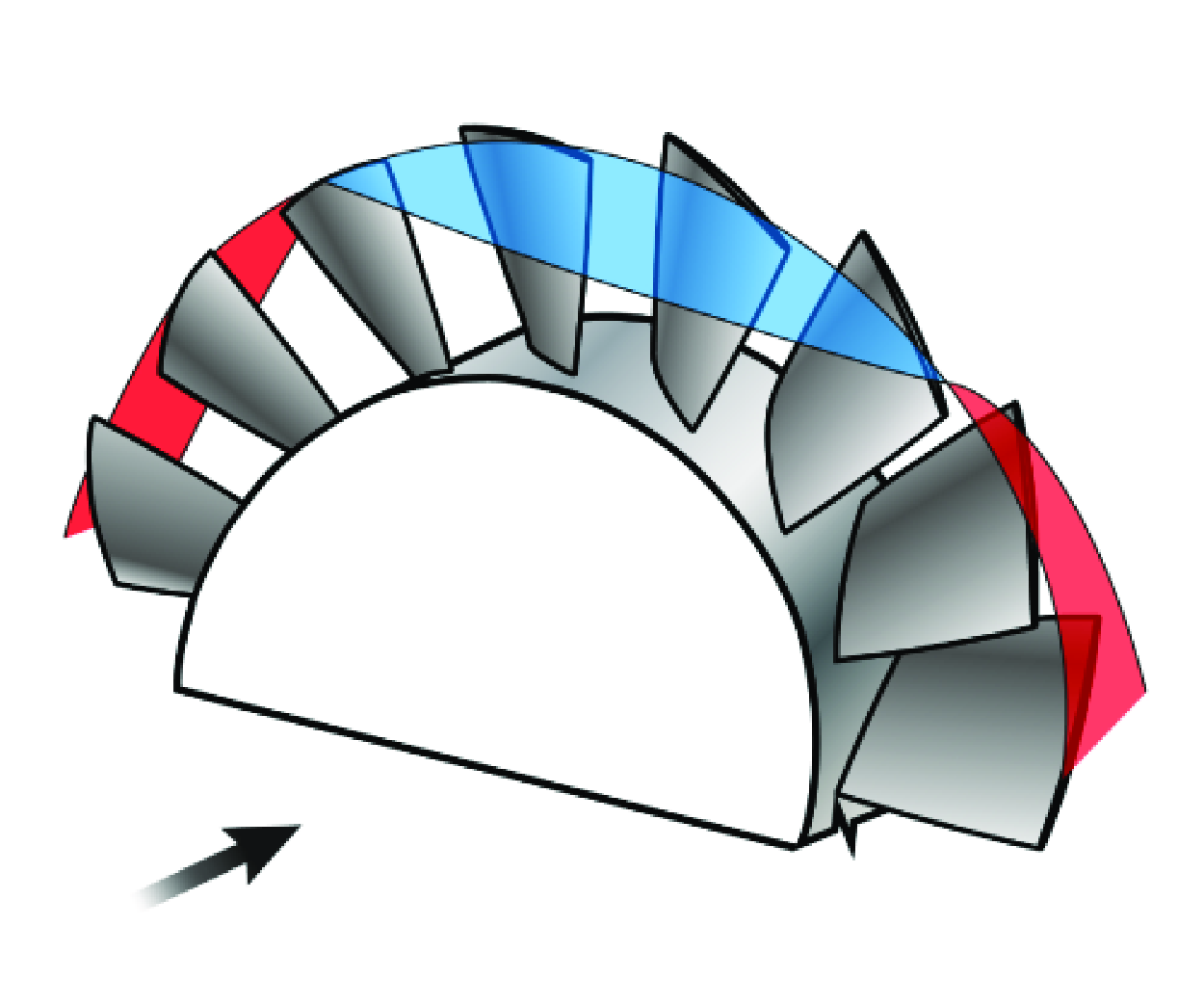

Figure 1. Schematic of a hard-walled annular cascade section and its acoustic scattering.

In this paper, we are devoted to the establishment of a fully 3-D acoustic resonance model for annular cascades in the presence of background mean flow. Such a model is developed in

![]() $\S$

2 based on our previously established 3-D cascade response (Shen, Wang & Sun Reference Shen, Wang, Sun, Zhang and Sun2022b

). A reduced quasi-3-D cascade of hub-to-tip ratio of 0.99 is first investigated in

$\S$

2 based on our previously established 3-D cascade response (Shen, Wang & Sun Reference Shen, Wang, Sun, Zhang and Sun2022b

). A reduced quasi-3-D cascade of hub-to-tip ratio of 0.99 is first investigated in

![]() $\S$

3 to reveal general characteristics. Solutions for a fully 3-D cascade are then presented in

$\S$

3 to reveal general characteristics. Solutions for a fully 3-D cascade are then presented in

![]() $\S$

4, including a comparison with the previous experimental results of Parker & Pryce (Reference Parker and Pryce1974). The effects of the background mean flow are studied in detail, and the mode scattering effect by the cascade shows significant influence on the characteristics of rotating acoustic resonances. Finally, discussions and conclusions are presented in

$\S$

4, including a comparison with the previous experimental results of Parker & Pryce (Reference Parker and Pryce1974). The effects of the background mean flow are studied in detail, and the mode scattering effect by the cascade shows significant influence on the characteristics of rotating acoustic resonances. Finally, discussions and conclusions are presented in

![]() $\S$

5.

$\S$

5.

2. Formulation

In this paper we consider a stationary annular cascade of

![]() $V$

straight flat plates of zero thickness and zero stagger, representing radially installed vanes. The cascade is positioned inside an infinite hard-walled duct with a uniform isentropic subsonic axial background mean flow of velocity

$V$

straight flat plates of zero thickness and zero stagger, representing radially installed vanes. The cascade is positioned inside an infinite hard-walled duct with a uniform isentropic subsonic axial background mean flow of velocity

![]() $U$

. As illustrated in figure 1, the cascade is of uniform hub radius

$U$

. As illustrated in figure 1, the cascade is of uniform hub radius

![]() $R_h$

, tip radius

$R_h$

, tip radius

![]() $R_d$

and chord length

$R_d$

and chord length

![]() $b$

, and the mean density and the speed of sound of the background mean flow are denoted as

$b$

, and the mean density and the speed of sound of the background mean flow are denoted as

![]() $\rho _0$

and

$\rho _0$

and

![]() $c_0$

, respectively. All perturbations are assumed to be small and linearisable, and an unsteady Kutta condition is applied to include the viscous effects. The thin-blade assumption is also applied as in previous theoretical models, since the experimental results of Parker (Reference Parker1966) indicate that the thickness of the blades has little effect on the acoustic resonance frequencies of the cascade. Besides, we try to establish a decoupled model to study the properties of the acoustic resonance modes themselves without any specific form of external aerodynamic/aeroelastic source. Accordingly, the thickness noise as well as the trailing-edge self-noise are neglected here. The insignificant quadrupole aeroacoustic source term can also be neglected (Goldstein Reference Goldstein1976, pp. 220–222); therefore, under high-Reynolds-number flow conditions where the viscous stresses on vanes are relatively small, the only dominant aeroacoustic source on cascade vanes is the dipole source caused by the unsteady pressure loading on vanes.

$c_0$

, respectively. All perturbations are assumed to be small and linearisable, and an unsteady Kutta condition is applied to include the viscous effects. The thin-blade assumption is also applied as in previous theoretical models, since the experimental results of Parker (Reference Parker1966) indicate that the thickness of the blades has little effect on the acoustic resonance frequencies of the cascade. Besides, we try to establish a decoupled model to study the properties of the acoustic resonance modes themselves without any specific form of external aerodynamic/aeroelastic source. Accordingly, the thickness noise as well as the trailing-edge self-noise are neglected here. The insignificant quadrupole aeroacoustic source term can also be neglected (Goldstein Reference Goldstein1976, pp. 220–222); therefore, under high-Reynolds-number flow conditions where the viscous stresses on vanes are relatively small, the only dominant aeroacoustic source on cascade vanes is the dipole source caused by the unsteady pressure loading on vanes.

To establish the acoustic transmission and scattering relations of the cascade, we choose two vertical virtual boundaries at the two sides of the cascade to form an isolated section, arbitrarily denoted as Section

![]() $K$

with an axial length

$K$

with an axial length

![]() $L_K$

. The upstream and the downstream non-reflective duct sections are denoted as Section

$L_K$

. The upstream and the downstream non-reflective duct sections are denoted as Section

![]() $K-1$

and Section

$K-1$

and Section

![]() $K+1$

, respectively. For the zero-sweep straight vanes,

$K+1$

, respectively. For the zero-sweep straight vanes,

![]() $L_K$

can be taken as

$L_K$

can be taken as

![]() $L_K=b$

such that the boundaries of Section

$L_K=b$

such that the boundaries of Section

![]() $K$

coincide with the leading-edge and the trailing-edge planes of the cascade but the section still contains the entire cascade. A cylindrical coordinate system

$K$

coincide with the leading-edge and the trailing-edge planes of the cascade but the section still contains the entire cascade. A cylindrical coordinate system

![]() $(r,\varphi ,z)$

is applied, and the left boundary is set as the zero point (

$(r,\varphi ,z)$

is applied, and the left boundary is set as the zero point (

![]() $z=0$

) of the axial coordinate when considering each section. Following classic duct acoustics (Tyler & Sofrin Reference Tyler and Sofrin1962), the downstream-propagating acoustic waves exiting Section

$z=0$

) of the axial coordinate when considering each section. Following classic duct acoustics (Tyler & Sofrin Reference Tyler and Sofrin1962), the downstream-propagating acoustic waves exiting Section

![]() $K$

at its right boundary can be denoted as

$K$

at its right boundary can be denoted as

\begin{align} p_{D,K}(r,\varphi ,z,t)=\sum _{m=-\infty }^{+\infty }\sum _{n=0}^{+\infty } D^{K}_{mn}\phi _m(k_{mn}r) \exp \!\big[\mathrm {i} m\varphi +\mathrm {i}\alpha _{1}^{(mn)} (z-L_K) - \mathrm {i}\omega t \big], \end{align}

\begin{align} p_{D,K}(r,\varphi ,z,t)=\sum _{m=-\infty }^{+\infty }\sum _{n=0}^{+\infty } D^{K}_{mn}\phi _m(k_{mn}r) \exp \!\big[\mathrm {i} m\varphi +\mathrm {i}\alpha _{1}^{(mn)} (z-L_K) - \mathrm {i}\omega t \big], \end{align}

and, similarly, outgoing acoustic waves propagating upstream from the left boundary of this section can be expressed as

\begin{align} p_{A,K}(r,\varphi ,z,t)=\sum _{m=-\infty }^{+\infty }\sum _{n=0}^{+\infty } A^{K}_{mn}\phi _m(k_{mn}r) \exp \!\big[\mathrm {i} m\varphi +\mathrm {i}\alpha _{2}^{(mn)} z - \mathrm {i}\omega t \big] , \end{align}

\begin{align} p_{A,K}(r,\varphi ,z,t)=\sum _{m=-\infty }^{+\infty }\sum _{n=0}^{+\infty } A^{K}_{mn}\phi _m(k_{mn}r) \exp \!\big[\mathrm {i} m\varphi +\mathrm {i}\alpha _{2}^{(mn)} z - \mathrm {i}\omega t \big] , \end{align}

where

![]() $\omega$

is the angular sound frequency,

$\omega$

is the angular sound frequency,

![]() $D^{K}_{mn}$

,

$D^{K}_{mn}$

,

![]() $A^{K}_{mn}$

are the mode amplitude coefficients and

$A^{K}_{mn}$

are the mode amplitude coefficients and

![]() $\phi _m(k_{mn}r)$

is the normalised radial eigenfunction of the hard-walled annular duct (see Sun & Wang Reference Sun and Wang2021, pp. 95–98) satisfying the orthogonality as

$\phi _m(k_{mn}r)$

is the normalised radial eigenfunction of the hard-walled annular duct (see Sun & Wang Reference Sun and Wang2021, pp. 95–98) satisfying the orthogonality as

![]() $\int _{R_h}^{R_d}\phi _m(k_{mi}r)\phi _m(k_{mj}r)r\mathrm {d}r=\delta _{ij}$

. Note that a circular cascade can then be easily considered with a simple replacement in the radial eigenfunction

$\int _{R_h}^{R_d}\phi _m(k_{mi}r)\phi _m(k_{mj}r)r\mathrm {d}r=\delta _{ij}$

. Note that a circular cascade can then be easily considered with a simple replacement in the radial eigenfunction

![]() $\phi _m(k_{mn}r)$

, although this paper focuses on annular cascades. Parameter

$\phi _m(k_{mn}r)$

, although this paper focuses on annular cascades. Parameter

![]() $k_{mn}$

is the corresponding eigenvalue of circumferential mode number

$k_{mn}$

is the corresponding eigenvalue of circumferential mode number

![]() $m$

and radial mode number

$m$

and radial mode number

![]() $n$

, and the acoustic duct modes are denoted as

$n$

, and the acoustic duct modes are denoted as

![]() $(m,n)$

modes, respectively. The downstream (

$(m,n)$

modes, respectively. The downstream (

![]() $\alpha _{1}^{(mn)}$

) and upstream (

$\alpha _{1}^{(mn)}$

) and upstream (

![]() $\alpha _{2}^{(mn)}$

) axial wavenumbers are

$\alpha _{2}^{(mn)}$

) axial wavenumbers are

Here

![]() $M=U/c_0$

is the Mach number of the background mean flow,

$M=U/c_0$

is the Mach number of the background mean flow,

![]() $k_0=\omega /c_0$

is the wavenumber of sound and

$k_0=\omega /c_0$

is the wavenumber of sound and

![]() $\beta$

is the Prandtl–Glauert transformation factor with

$\beta$

is the Prandtl–Glauert transformation factor with

![]() $\beta = \sqrt {1-M^2}$

. Note that in search of a resonance characteristic frequency whose real part

$\beta = \sqrt {1-M^2}$

. Note that in search of a resonance characteristic frequency whose real part

![]() ${\rm Re}(\omega )$

represents the oscillation time period and imaginary part

${\rm Re}(\omega )$

represents the oscillation time period and imaginary part

![]() ${\rm Im}(\omega )$

indicates the growth rate of the resonance mode amplitude as time increases,

${\rm Im}(\omega )$

indicates the growth rate of the resonance mode amplitude as time increases,

![]() $\omega$

and in turn the acoustic wavenumber

$\omega$

and in turn the acoustic wavenumber

![]() $k_0$

are treated as complex numbers, whereas

$k_0$

are treated as complex numbers, whereas

![]() $\kappa _{nm}$

are chosen directly following the causality condition.

$\kappa _{nm}$

are chosen directly following the causality condition.

The duct is assumed to be hard-walled with constant cross-sections at the virtual boundaries, so there should be no acoustic scattering and the pressure waves propagate continuously across these boundaries. As a result, the acoustic waves entering the left boundary of Section

![]() $K$

should be equal to the exiting waves of the upstream section (Section

$K$

should be equal to the exiting waves of the upstream section (Section

![]() $K-1$

) at its right boundary. These incident waves are then expressed as

$K-1$

) at its right boundary. These incident waves are then expressed as

\begin{align} p_{D,K-1}(r,\varphi ,z,t)=\sum _{m=-\infty }^{+\infty }\sum _{n=0}^{+\infty } D^{K-1}_{mn}\phi _m(k_{mn}r) \exp \!\big[\mathrm {i} m\varphi +\mathrm {i}\alpha _{1}^{(mn)} z - \mathrm {i}\omega t \big] . \end{align}

\begin{align} p_{D,K-1}(r,\varphi ,z,t)=\sum _{m=-\infty }^{+\infty }\sum _{n=0}^{+\infty } D^{K-1}_{mn}\phi _m(k_{mn}r) \exp \!\big[\mathrm {i} m\varphi +\mathrm {i}\alpha _{1}^{(mn)} z - \mathrm {i}\omega t \big] . \end{align}

Similarly, the upstream waves propagating inward Section

![]() $K$

at its right boundary are the exiting waves of the next section

$K$

at its right boundary are the exiting waves of the next section

![]() $K+1$

, which are expressed as

$K+1$

, which are expressed as

\begin{align} p_{A,K+1}(r,\varphi ,z,t)=\sum _{m=-\infty }^{+\infty }\sum _{n=0}^{+\infty } A^{K+1}_{mn}\phi _m(k_{mn}r) \exp \big[\mathrm {i} m\varphi +\mathrm {i}\alpha _{2}^{(mn)}( z-L_K) - \mathrm {i}\omega t \big] . \end{align}

\begin{align} p_{A,K+1}(r,\varphi ,z,t)=\sum _{m=-\infty }^{+\infty }\sum _{n=0}^{+\infty } A^{K+1}_{mn}\phi _m(k_{mn}r) \exp \big[\mathrm {i} m\varphi +\mathrm {i}\alpha _{2}^{(mn)}( z-L_K) - \mathrm {i}\omega t \big] . \end{align}

If we further denote the upstream- and downstream-propagating waves scattered from the cascade solid surfaces as

![]() $p_{s,u}$

and

$p_{s,u}$

and

![]() $p_{d,u}$

, then the relationship between the acoustic waves at the two virtual boundaries of Section

$p_{d,u}$

, then the relationship between the acoustic waves at the two virtual boundaries of Section

![]() $K$

can be written as

$K$

can be written as

Because the mode eigenfunctions are completely orthogonal and there exists no scattering at the section boundaries, the above equations are equivalent to the requirement that for each duct mode

![]() $(m,n)$

the corresponding mode amplitude coefficients satisfy the equations described in (2.6). Therefore, if the mode amplitudes of the scattered waves

$(m,n)$

the corresponding mode amplitude coefficients satisfy the equations described in (2.6). Therefore, if the mode amplitudes of the scattered waves

![]() $p_{s,u}$

and

$p_{s,u}$

and

![]() $p_{s,d}$

can be expressed as a function of the incident waves, the acoustic propagation and scattering relationship of the cascade can be fully described by (2.6) using four sets of amplitude coefficients:

$p_{s,d}$

can be expressed as a function of the incident waves, the acoustic propagation and scattering relationship of the cascade can be fully described by (2.6) using four sets of amplitude coefficients:

![]() $\{D^{K-1}_{mn}\}$

,

$\{D^{K-1}_{mn}\}$

,

![]() $\{A^{K}_{mn}\}$

,

$\{A^{K}_{mn}\}$

,

![]() $\{D^{K}_{mn}\}$

and

$\{D^{K}_{mn}\}$

and

![]() $\{A^{K+1}_{mn}\}$

.

$\{A^{K+1}_{mn}\}$

.

2.1. Wave scattering

The acoustic scattering of the cascade is described based on our previously established cascade response model (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Wang, Sun, Zhang and Sun2022b ), which is an extension of the 3-D lifting surface method developed by Namba (Reference Namba1972, Reference Namba1977, Reference Namba1987). Using the generalised Lighthill equation by Goldstein (Reference Goldstein1976, pp. 189–192), the scattered pressure field of the thin-blade cascade under high-Reynolds-number background mean flow can be expressed as

neglecting the insignificant monopole source terms, the volume turbulence quadrupole source terms and the sound radiation caused by the viscous stress dipoles on vane surfaces (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Wang, Sun, Zhang and Sun2022b

). Here and after, the coordinates with superscript

![]() $^{\prime}$

represent those of the source point and otherwise the observation point. Time

$^{\prime}$

represent those of the source point and otherwise the observation point. Time

![]() $t$

is the time of observation,

$t$

is the time of observation,

![]() $\tau$

is the time of source and

$\tau$

is the time of source and

![]() $\boldsymbol {x,y}$

are respectively the spatial coordinate vectors of the observation point and the source point. Function

$\boldsymbol {x,y}$

are respectively the spatial coordinate vectors of the observation point and the source point. Function

![]() $G$

is the Green’s function for an infinite hard-walled annular duct with a uniform subsonic axial background mean flow, satisfying Lighthill’s wave equation (Lighthill Reference Lighthill1952) and a boundary condition of zero normal derivative at duct walls. The surface integration

$G$

is the Green’s function for an infinite hard-walled annular duct with a uniform subsonic axial background mean flow, satisfying Lighthill’s wave equation (Lighthill Reference Lighthill1952) and a boundary condition of zero normal derivative at duct walls. The surface integration

![]() $\int _{S(\tau )}(\cdot ) \mathrm {d}S(\boldsymbol {y})$

takes place over the vanes, and the derivative normal to the surfaces is

$\int _{S(\tau )}(\cdot ) \mathrm {d}S(\boldsymbol {y})$

takes place over the vanes, and the derivative normal to the surfaces is

![]() ${\partial }/{(r^{\prime}\partial \varphi ^{\prime})}$

for the radially placed vanes with which we studied. The dominant aeroacoustic source during acoustic scattering is the unsteady pressure difference

${\partial }/{(r^{\prime}\partial \varphi ^{\prime})}$

for the radially placed vanes with which we studied. The dominant aeroacoustic source during acoustic scattering is the unsteady pressure difference

![]() $\Delta P_s$

between the two sides of the vanes.

$\Delta P_s$

between the two sides of the vanes.

In the cylindrical coordinate system illustrated in figure 1, the Green’s function of the hard-walled duct can be expressed as (Sun & Wang Reference Sun and Wang2021, pp. 92–98)

\begin{align} G(r,\varphi ,z,t\ &\vert \ r^{\prime},\varphi ^{\prime},z^{\prime},\tau ) =\frac {1}{4\pi ^2}\sum _{m=-\infty }^{+\infty }\sum _{n=0}^{+\infty } \frac {\phi _m(k_{mn}r) \phi _m(k_{mn}r^{\prime})}{2\pi } \exp [\mathrm {i}m(\varphi -\varphi ^{\prime})] \nonumber \\[3pt] &\mbox {}\times \int _{-\infty }^{+\infty } \int _{-\infty }^{+\infty } \frac {\exp [\mathrm {i}\alpha (z-z^{\prime})]}{\beta ^2\alpha ^2 + 2Mk_0\alpha -k_0^2+k_{mn}^2} \exp [-\mathrm {i}\omega ^{\prime}(t-\tau )] \,\mathrm {d}\alpha \,\mathrm {d}\omega ^{\prime} .\end{align}

\begin{align} G(r,\varphi ,z,t\ &\vert \ r^{\prime},\varphi ^{\prime},z^{\prime},\tau ) =\frac {1}{4\pi ^2}\sum _{m=-\infty }^{+\infty }\sum _{n=0}^{+\infty } \frac {\phi _m(k_{mn}r) \phi _m(k_{mn}r^{\prime})}{2\pi } \exp [\mathrm {i}m(\varphi -\varphi ^{\prime})] \nonumber \\[3pt] &\mbox {}\times \int _{-\infty }^{+\infty } \int _{-\infty }^{+\infty } \frac {\exp [\mathrm {i}\alpha (z-z^{\prime})]}{\beta ^2\alpha ^2 + 2Mk_0\alpha -k_0^2+k_{mn}^2} \exp [-\mathrm {i}\omega ^{\prime}(t-\tau )] \,\mathrm {d}\alpha \,\mathrm {d}\omega ^{\prime} .\end{align}

Substituting (2.8) into (2.7) and using the residue theorem to solve for the infinite integral of the axial wavenumber

![]() $\alpha$

, the scattered sound field can be obtained as an integral of the unknown unsteady pressure loading

$\alpha$

, the scattered sound field can be obtained as an integral of the unknown unsteady pressure loading

![]() $\Delta P_s$

on the cascade vanes. Considering the circumferential periodicity of the pressure disturbances, the integral can be further simplified to the integral of the unsteady loading distribution

$\Delta P_s$

on the cascade vanes. Considering the circumferential periodicity of the pressure disturbances, the integral can be further simplified to the integral of the unsteady loading distribution

![]() $\Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime})\exp (-\mathrm {i}\omega t)$

on a single reference vane at

$\Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime})\exp (-\mathrm {i}\omega t)$

on a single reference vane at

![]() $\varphi ^{\prime}=0$

(for details, see Shen et al. (Reference Shen, Wang, Sun, Zhang and Sun2022b

)). If we use

$\varphi ^{\prime}=0$

(for details, see Shen et al. (Reference Shen, Wang, Sun, Zhang and Sun2022b

)). If we use

![]() $\sigma$

to denote the inter-blade phase angle of the incident disturbances as well as the unsteady pressure loading

$\sigma$

to denote the inter-blade phase angle of the incident disturbances as well as the unsteady pressure loading

![]() $\Delta P_s$

on vanes (as illustrated in figure 1), the scattered pressure fields downstream and upstream of the cascade are obtained as

$\Delta P_s$

on vanes (as illustrated in figure 1), the scattered pressure fields downstream and upstream of the cascade are obtained as

\begin{align} p_{s,d/u}(\boldsymbol {x},t) & = \exp (-\mathrm {i}\omega t)\sum _{q=-\infty }^{+\infty }\sum _{n=0}^{+\infty }\phi _m(k_{mn}r) \exp (\mathrm {i}m\varphi ) \int _{S_1(\tau )}\frac {mV}{4\pi \kappa _{nm}r^{\prime}} \phi _m(k_{mn}r^{\prime}) \nonumber \\[3pt] & \quad \times \Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime}) \left \{ \mathrm {H}(\pm z \mp z^{\prime})\exp \big[\mathrm {i}\alpha_{1,2}^{(m,n)}(z-z^{\prime})\big] \right \} \mathrm {d}S(\boldsymbol {y}) ,\quad m=\frac {V\sigma }{2\pi }-qV. \end{align}

\begin{align} p_{s,d/u}(\boldsymbol {x},t) & = \exp (-\mathrm {i}\omega t)\sum _{q=-\infty }^{+\infty }\sum _{n=0}^{+\infty }\phi _m(k_{mn}r) \exp (\mathrm {i}m\varphi ) \int _{S_1(\tau )}\frac {mV}{4\pi \kappa _{nm}r^{\prime}} \phi _m(k_{mn}r^{\prime}) \nonumber \\[3pt] & \quad \times \Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime}) \left \{ \mathrm {H}(\pm z \mp z^{\prime})\exp \big[\mathrm {i}\alpha_{1,2}^{(m,n)}(z-z^{\prime})\big] \right \} \mathrm {d}S(\boldsymbol {y}) ,\quad m=\frac {V\sigma }{2\pi }-qV. \end{align}

Here

![]() $\mathrm {H}(\cdot )$

denotes the Heaviside function. Besides, the surface integral domain also reduces to that of one single vane

$\mathrm {H}(\cdot )$

denotes the Heaviside function. Besides, the surface integral domain also reduces to that of one single vane

![]() $S_1(\tau )$

located at

$S_1(\tau )$

located at

![]() $\varphi ^{\prime}=0$

.

$\varphi ^{\prime}=0$

.

Referring to the linearised inviscid momentum equation, the circumferential induced velocity of the scattered field is obtained as

\begin{align} v_\varphi (\boldsymbol {x},t) = & -\frac {V\mathrm {e}^{-\mathrm {i}\omega t}}{2\pi \rho _0 U}\sum _{q=-\infty }^{+\infty }\sum _{n=0}^{+\infty }\frac {m}{r}\phi _m(k_{mn}r)\exp (\mathrm {i}m\varphi ) \int _{S_1(\tau )}\frac {m}{r^{\prime}} \phi _m(k_{mn}r^{\prime}) \Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime}) \nonumber \\[3pt] &\mbox {}\times \left \{\mathrm {H}(z-z^{\prime})[Q_1 +Q_3] + \mathrm {H}(z^{\prime}-z) Q_2 \right \} \mathrm {d}S(\boldsymbol {y}) ,\quad m=\frac {V\sigma }{2\pi }-qV, \end{align}

\begin{align} v_\varphi (\boldsymbol {x},t) = & -\frac {V\mathrm {e}^{-\mathrm {i}\omega t}}{2\pi \rho _0 U}\sum _{q=-\infty }^{+\infty }\sum _{n=0}^{+\infty }\frac {m}{r}\phi _m(k_{mn}r)\exp (\mathrm {i}m\varphi ) \int _{S_1(\tau )}\frac {m}{r^{\prime}} \phi _m(k_{mn}r^{\prime}) \Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime}) \nonumber \\[3pt] &\mbox {}\times \left \{\mathrm {H}(z-z^{\prime})[Q_1 +Q_3] + \mathrm {H}(z^{\prime}-z) Q_2 \right \} \mathrm {d}S(\boldsymbol {y}) ,\quad m=\frac {V\sigma }{2\pi }-qV, \end{align}

where the coefficients are

\begin{align} Q_{1,2} = \frac {M\beta ^2\exp\!\big [\mathrm {i}\alpha _{1,2}^{(mn)}(z-z^{\prime}) \big]}{2\kappa _{nm}(\pm M\kappa _{nm}-k_0)}, \quad Q_3 = \frac {M^2 \exp [{\rm i}\alpha _3(z-z^{\prime})]}{k_0^2+M^2 k_{mn}^2}, \end{align}

\begin{align} Q_{1,2} = \frac {M\beta ^2\exp\!\big [\mathrm {i}\alpha _{1,2}^{(mn)}(z-z^{\prime}) \big]}{2\kappa _{nm}(\pm M\kappa _{nm}-k_0)}, \quad Q_3 = \frac {M^2 \exp [{\rm i}\alpha _3(z-z^{\prime})]}{k_0^2+M^2 k_{mn}^2}, \end{align}

and the axial wavenumber of shed vortical waves is

![]() $\alpha _3=\omega /U=k_0/M$

. The integral terms with

$\alpha _3=\omega /U=k_0/M$

. The integral terms with

![]() $Q_{1,2}$

correspond to the velocity induced by the downstream- and upstream-propagating acoustic waves, and the integral term with

$Q_{1,2}$

correspond to the velocity induced by the downstream- and upstream-propagating acoustic waves, and the integral term with

![]() $Q_3$

corresponds to the velocity induced by the shed vortical waves. In addition, the circumferential particle velocity of any propagating acoustic waves with mode amplitude coefficient

$Q_3$

corresponds to the velocity induced by the shed vortical waves. In addition, the circumferential particle velocity of any propagating acoustic waves with mode amplitude coefficient

![]() $A_{mn}$

can also be derived as

$A_{mn}$

can also be derived as

\begin{align} u_\varphi =-\frac {1}{\rho _0 U }\frac {m}{\big(\alpha _{1,2}^{(mn)}-\alpha _3 \big)r} A_{mn}\phi _m(k_{mn}r) \exp \!\big[\mathrm {i} m\varphi +\mathrm {i}\alpha _{1,2}^{(mn)} z - \mathrm {i}\omega t \big] . \end{align}

\begin{align} u_\varphi =-\frac {1}{\rho _0 U }\frac {m}{\big(\alpha _{1,2}^{(mn)}-\alpha _3 \big)r} A_{mn}\phi _m(k_{mn}r) \exp \!\big[\mathrm {i} m\varphi +\mathrm {i}\alpha _{1,2}^{(mn)} z - \mathrm {i}\omega t \big] . \end{align}

On the vane surfaces, the upwash velocities should satisfy the zero normal velocity boundary condition for a solid cascade:

Substituting (2.10) and (2.12) into (2.13) and dropping the time harmonic factor

![]() $\exp (-\mathrm {i}\omega t)$

, we can establish an integral equation about the unknown dipole source distribution

$\exp (-\mathrm {i}\omega t)$

, we can establish an integral equation about the unknown dipole source distribution

![]() $\Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime})$

with any given incident acoustic wave, including the previously described incident waves (2.4) and (2.5). Then we can numerically solve the integral equation to obtain

$\Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime})$

with any given incident acoustic wave, including the previously described incident waves (2.4) and (2.5). Then we can numerically solve the integral equation to obtain

![]() $\Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime})$

and derive the mode amplitude coefficients of the scattered sound field

$\Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime})$

and derive the mode amplitude coefficients of the scattered sound field

![]() $p_{s,u}$

and

$p_{s,u}$

and

![]() $p_{s,d}$

using (2.9).

$p_{s,d}$

using (2.9).

2.2. Solution of characteristic frequencies

A collocation method is applied to solve the integral equation (2.13) established above. Within the linear range where there is no flow separation, the unsteady Kutta condition of subsonic background mean flow can be applied in a similar way to the steady case (Crighton Reference Crighton1985). Following the hybrid method proposed by Namba (Reference Namba1987), the unsteady pressure loading

![]() $\Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime})$

can be expanded as

$\Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime})$

can be expanded as

\begin{align} \Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime}) \big |_{r^{\prime}=R_h + (2j^{\prime}-1)(R_d-R_h)/(2J)}=\left [ B_{1j^{\prime}} \cot \left (\frac {\xi ^{\prime}}{2}\right ) + \sum _{i^{\prime}=2}^{I}B_{i^{\prime}j^{\prime}}\sin \big ((i^{\prime}-1)\xi ^{\prime}\big ) \right ] , \end{align}

\begin{align} \Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime}) \big |_{r^{\prime}=R_h + (2j^{\prime}-1)(R_d-R_h)/(2J)}=\left [ B_{1j^{\prime}} \cot \left (\frac {\xi ^{\prime}}{2}\right ) + \sum _{i^{\prime}=2}^{I}B_{i^{\prime}j^{\prime}}\sin \big ((i^{\prime}-1)\xi ^{\prime}\big ) \right ] , \end{align}

with

![]() $I$

axial terms and

$I$

axial terms and

![]() $J$

radial terms, and the distribution of

$J$

radial terms, and the distribution of

![]() $\Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime})$

can therefore be represented by a series of expansion coefficients

$\Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime})$

can therefore be represented by a series of expansion coefficients

![]() $\{B_{i^{\prime}j^{\prime}}\}$

. In the radial direction,

$\{B_{i^{\prime}j^{\prime}}\}$

. In the radial direction,

![]() $\Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime})$

is discretised and the subscript

$\Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime})$

is discretised and the subscript

![]() $j^{\prime}$

denotes the radial positions of each slice. This could provide convenience to consider swept vanes in future studies. In the axial direction, the distribution of

$j^{\prime}$

denotes the radial positions of each slice. This could provide convenience to consider swept vanes in future studies. In the axial direction, the distribution of

![]() $\Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime})$

is expanded as cotangent and sine functions. In addition, Glauert’s transformation is applied to the axial coordinates for both the source position

$\Delta P_s(r^{\prime},z^{\prime})$

is expanded as cotangent and sine functions. In addition, Glauert’s transformation is applied to the axial coordinates for both the source position

![]() $z^{\prime}$

and the observation location

$z^{\prime}$

and the observation location

![]() $z$

as

$z$

as

The unsteady Kutta condition is inherently applied here (Rienstra Reference Rienstra1992). The convergence of numerical solution is checked a posteriori. If the solution of the series (2.14) converges, it should converge to the Kutta solution, i.e. the physical solution which satisfies the experimental results with practical viscosity effects (Crighton Reference Crighton1985). After dropping the time harmonic factor

![]() $\exp (-\mathrm {i}\omega t)$

, the integral equation (2.13) is then enforced at

$\exp (-\mathrm {i}\omega t)$

, the integral equation (2.13) is then enforced at

![]() $J \times I$

evenly spaced control points at observation positions

$J \times I$

evenly spaced control points at observation positions

![]() $(r_j,\xi _i)$

, where

$(r_j,\xi _i)$

, where

The left-hand side of the equation is numerically integrated using the trapezoidal rule at axial source points similar to that in Whitehead (Reference Whitehead1962), with the unsteady loading source expansion (2.14) substituted in. Therefore, the integral equation (2.13) is finally discretised into a system of linear equations written in a matrix equation form as

similar to the process in Shen et al. (Reference Shen, Wang, Sun, Zhang and Sun2022b

). Here the square matrix

![]() $\unicode{x1D648}$

correlates the dipole expansion coefficients

$\unicode{x1D648}$

correlates the dipole expansion coefficients

![]() ${\boldsymbol{B}}_{i^{\prime}j^{\prime}}$

to the induced velocity

${\boldsymbol{B}}_{i^{\prime}j^{\prime}}$

to the induced velocity

![]() ${\boldsymbol{u}}_{\varphi ,ij}$

at the control points on vanes.

${\boldsymbol{u}}_{\varphi ,ij}$

at the control points on vanes.

Now we can establish the scattering equations between the incident and out-going amplitude coefficients

![]() $\{D^{K-1}_{mn}\}$

,

$\{D^{K-1}_{mn}\}$

,

![]() $\{A^{K}_{mn}\}$

,

$\{A^{K}_{mn}\}$

,

![]() $\{D^{K}_{mn}\}$

and

$\{D^{K}_{mn}\}$

and

![]() $\{A^{K+1}_{mn}\}$

. Firstly, a main circumferential mode number

$\{A^{K+1}_{mn}\}$

. Firstly, a main circumferential mode number

![]() $m_0$

is chosen, corresponding to an inter-blade phase angle

$m_0$

is chosen, corresponding to an inter-blade phase angle

![]() $\sigma =2\pi m_0 / V$

. The radial modes are then truncated at

$\sigma =2\pi m_0 / V$

. The radial modes are then truncated at

![]() $n=N$

and the circumferential modes

$n=N$

and the circumferential modes

![]() $m=m_0+qV$

are truncated at

$m=m_0+qV$

are truncated at

![]() $m=m_0\pm MV$

, such that each amplitude coefficient vector

$m=m_0\pm MV$

, such that each amplitude coefficient vector

![]() $\boldsymbol {D/A}^{\sim }_{mn}$

has a total of

$\boldsymbol {D/A}^{\sim }_{mn}$

has a total of

![]() $(2M+1)\times N$

terms. Accordingly, the upwash velocity vector

$(2M+1)\times N$

terms. Accordingly, the upwash velocity vector

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}_{\varphi ,ij}$

induced by the incident coefficients

$\boldsymbol {u}_{\varphi ,ij}$

induced by the incident coefficients

![]() $\{D^{K-1}_{mn}\}$

and

$\{D^{K-1}_{mn}\}$

and

![]() $\{A^{K+1}_{mn}\}$

can be calculated as

$\{A^{K+1}_{mn}\}$

can be calculated as

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}_{\varphi ,ij}=\unicode{x1D64F}^{D}_{ij,mn}\boldsymbol {D}^{K-1}_{mn}(\mathrm {or}\ \unicode{x1D64F}^{A}_{ij,mn}\boldsymbol {A}^{K+1}_{mn})$

using matrices

$\boldsymbol {u}_{\varphi ,ij}=\unicode{x1D64F}^{D}_{ij,mn}\boldsymbol {D}^{K-1}_{mn}(\mathrm {or}\ \unicode{x1D64F}^{A}_{ij,mn}\boldsymbol {A}^{K+1}_{mn})$

using matrices

\begin{align} \unicode{x1D64F}^{D(A)}_{ij,mn}=\frac {1}{\rho _0 U}\frac {m}{r_j}\frac {\phi _m(k_{mn}r_j) \exp\!\big[\mathrm {i} \alpha _{1(2)}^{(mn)} (z_i - 0.5 L_K\pm 0.5L_K) \big]}{\alpha _{1(2)}^{(mn)}-\omega /U} , \end{align}

\begin{align} \unicode{x1D64F}^{D(A)}_{ij,mn}=\frac {1}{\rho _0 U}\frac {m}{r_j}\frac {\phi _m(k_{mn}r_j) \exp\!\big[\mathrm {i} \alpha _{1(2)}^{(mn)} (z_i - 0.5 L_K\pm 0.5L_K) \big]}{\alpha _{1(2)}^{(mn)}-\omega /U} , \end{align}

by referring to (2.12). The acoustic mode amplitude coefficients of the scattered field can be calculated by matrix multiplication

![]() $\unicode{x1D64E}^{D(A)}_{mn,i^{\prime}j^{\prime}} \boldsymbol {B}_{i^{\prime}j^{\prime}}$

, corresponding to the numerical integration of (2.9) with the unsteady loading expansion (2.14). Therefore, the scattering relations restricted by (2.6) can be finally rearranged and rewritten as a matrix equation with the incident wave amplitudes on the right-hand side:

$\unicode{x1D64E}^{D(A)}_{mn,i^{\prime}j^{\prime}} \boldsymbol {B}_{i^{\prime}j^{\prime}}$

, corresponding to the numerical integration of (2.9) with the unsteady loading expansion (2.14). Therefore, the scattering relations restricted by (2.6) can be finally rearranged and rewritten as a matrix equation with the incident wave amplitudes on the right-hand side:

\begin{align} \unicode{x1D653}(\omega )\left [ \begin{array}{c} \boldsymbol {A}^{K}_{mn} \\[3pt] \displaystyle \boldsymbol {D}^{K}_{mn} \end{array} \right ] =\left [\begin{array}{c@{\quad}c} \unicode{x1D668}\unicode{x1D668}_{LL}\ &\ \unicode{x1D668}\unicode{x1D668}_{RL} \\[3pt] \displaystyle \unicode{x1D668}\unicode{x1D668}_{LR}\ &\ \unicode{x1D668}\unicode{x1D668}_{RR} \end{array} \right ] ^{-1} \left [ \begin{array}{c} \boldsymbol {A}^{K}_{mn} \\[3pt] \displaystyle \boldsymbol {D}^{K}_{mn} \end{array} \right ] =\left [ \begin{array}{c} \boldsymbol {D}^{K-1}_{\mu \nu } \\[3pt] \displaystyle \boldsymbol {A}^{K+1}_{\mu \nu } \end{array} \right ] , \end{align}

\begin{align} \unicode{x1D653}(\omega )\left [ \begin{array}{c} \boldsymbol {A}^{K}_{mn} \\[3pt] \displaystyle \boldsymbol {D}^{K}_{mn} \end{array} \right ] =\left [\begin{array}{c@{\quad}c} \unicode{x1D668}\unicode{x1D668}_{LL}\ &\ \unicode{x1D668}\unicode{x1D668}_{RL} \\[3pt] \displaystyle \unicode{x1D668}\unicode{x1D668}_{LR}\ &\ \unicode{x1D668}\unicode{x1D668}_{RR} \end{array} \right ] ^{-1} \left [ \begin{array}{c} \boldsymbol {A}^{K}_{mn} \\[3pt] \displaystyle \boldsymbol {D}^{K}_{mn} \end{array} \right ] =\left [ \begin{array}{c} \boldsymbol {D}^{K-1}_{\mu \nu } \\[3pt] \displaystyle \boldsymbol {A}^{K+1}_{\mu \nu } \end{array} \right ] , \end{align}

where

To solve for the acoustic resonances of the isolated cascade, we assume zero incident waves and zero reflections at the upstream and downstream boundaries. The acoustic resonance states then correspond to the non-zero solutions of the scattering equation (2.19) with zero right-hand side, i.e.

![]() $\boldsymbol {D}^{K-1}_{\mu \nu } =\boldsymbol {A}^{K+1}_{\mu \nu }=\boldsymbol {0}$

. The resonance characteristic frequencies can thus be calculated by the existence condition of such non-zero solutions,

$\boldsymbol {D}^{K-1}_{\mu \nu } =\boldsymbol {A}^{K+1}_{\mu \nu }=\boldsymbol {0}$

. The resonance characteristic frequencies can thus be calculated by the existence condition of such non-zero solutions,

![]() $\det [\unicode{x1D653}(\omega )]=0$

, which is equivalent to the requirement that matrix

$\det [\unicode{x1D653}(\omega )]=0$

, which is equivalent to the requirement that matrix

![]() $\unicode{x1D653}(\omega )$

is singular at the resonance frequency.

$\unicode{x1D653}(\omega )$

is singular at the resonance frequency.

Note that the interactions between the vortical waves shed from the trailing edges of the cascade and other downstream structures in the duct are temporarily ignored, such that they induce no acoustic waves propagating backward to Section

![]() $K$

from the downstream section. As a result, the vortical waves shed by the thin-blade cascade are not included in the scattering relation (2.19) for simplicity, but they can be easily added to the equations similar to that in Hanson (Reference Hanson1997) or Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Wang, Du and Sun2019) if needed. More complex geometries can be considered in the future by further extending the present model to include more sections and using similar non-scattering boundary conditions to connect them together and form a larger matrix

$K$

from the downstream section. As a result, the vortical waves shed by the thin-blade cascade are not included in the scattering relation (2.19) for simplicity, but they can be easily added to the equations similar to that in Hanson (Reference Hanson1997) or Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Wang, Du and Sun2019) if needed. More complex geometries can be considered in the future by further extending the present model to include more sections and using similar non-scattering boundary conditions to connect them together and form a larger matrix

![]() $\unicode{x1D653}(\omega )$

for the solution of characteristic frequencies. In this paper, however, we focus on the most general cascade resonance characteristics by studying one single isolated stator section.

$\unicode{x1D653}(\omega )$

for the solution of characteristic frequencies. In this paper, however, we focus on the most general cascade resonance characteristics by studying one single isolated stator section.

The effect of swirl flow is also temporarily not included, due to the lack of an appropriate analytic Green’s function for 3-D swirled annular flow. Only zero-stagger stator cascades can be strictly considered using the present model. But as shown in Koch (Reference Koch1983), the effect of swirl (or stagger angle) on resonance frequencies is significant when the stagger angle exceeds

![]() $30^\circ$

, but is much less profound otherwise. Therefore, at the inlet/outlet stages of a fan/compressor where there only exists mild swirl, the above model should be able to provide a good prediction for the acoustic resonances in practical cascades.

$30^\circ$

, but is much less profound otherwise. Therefore, at the inlet/outlet stages of a fan/compressor where there only exists mild swirl, the above model should be able to provide a good prediction for the acoustic resonances in practical cascades.

The commonly used singular value decomposition (SVD) method (as in Woodley & Peake Reference Woodley and Peake1999a

) is applied to search for the complex characteristic frequencies at which the scattering matrix

![]() $\unicode{x1D653}(\omega )$

is singular. The matrix

$\unicode{x1D653}(\omega )$

is singular. The matrix

![]() $\unicode{x1D653}(\omega )$

for a given frequency

$\unicode{x1D653}(\omega )$

for a given frequency

![]() $\omega$

is factorised as a product of two orthogonal matrices and a real diagonal matrix

$\omega$

is factorised as a product of two orthogonal matrices and a real diagonal matrix

![]() $\unicode{x1D63F}$

using the SVD method, and the condition number of the original matrix can then be calculated by the ratio between the largest and smallest elements of the diagonal matrix

$\unicode{x1D63F}$

using the SVD method, and the condition number of the original matrix can then be calculated by the ratio between the largest and smallest elements of the diagonal matrix

![]() $\unicode{x1D63F}$

. Finally, a self-adaptive local mesh refinement method is applied to locate the maximum points for the condition number of matrix

$\unicode{x1D63F}$

. Finally, a self-adaptive local mesh refinement method is applied to locate the maximum points for the condition number of matrix

![]() $\unicode{x1D653}(\omega )$

in the complex frequency plane, which should be the resonance frequencies corresponding to different non-zero solutions (different acoustic resonance modes). Similar to the previous 2-D model by Woodley & Peake (Reference Woodley and Peake1999a

), the resonance results converge rapidly with truncation number

$\unicode{x1D653}(\omega )$

in the complex frequency plane, which should be the resonance frequencies corresponding to different non-zero solutions (different acoustic resonance modes). Similar to the previous 2-D model by Woodley & Peake (Reference Woodley and Peake1999a

), the resonance results converge rapidly with truncation number

![]() $M$

and

$M$

and

![]() $N$

such that just a few additional cut-off modes are needed in the calculations.

$N$

such that just a few additional cut-off modes are needed in the calculations.

3. Resonances with a reduced quasi-3-D cascade

We first simplify our model to a quasi-3-D case with annular cascades of hub-to-tip ratio 0.99, in order to reveal general characteristics about the rotating resonance modes under non-zero background mean flow. In this case only the first radial mode

![]() $n=0$

is considered. Comparison is first made with the ideal 2-D results for the stationary Parker modes predicted by the Wiener–Hopf method (Koch Reference Koch1983), as shown in figure 2. There is no stagger for both stator cascades, and the geometry and flow parameters for the quasi-3-D annular cascade are chosen to be

$n=0$

is considered. Comparison is first made with the ideal 2-D results for the stationary Parker modes predicted by the Wiener–Hopf method (Koch Reference Koch1983), as shown in figure 2. There is no stagger for both stator cascades, and the geometry and flow parameters for the quasi-3-D annular cascade are chosen to be

Correspondingly, the chord-to-pitch ratio is varied by changing the chord length

![]() $b$

in the present model. Our predictions for both the real parts and the imaginary parts of the resonance frequencies

$b$

in the present model. Our predictions for both the real parts and the imaginary parts of the resonance frequencies

![]() $\omega _k$

of Parker’s

$\omega _k$

of Parker’s

![]() $\beta$

mode match well with the 2-D results of Koch.

$\beta$

mode match well with the 2-D results of Koch.

Figure 2. Comparison between (a) the real parts and (b) the imaginary parts of the resonance frequencies predicted by the present model and results of the 2-D model (figure 5 in Koch (Reference Koch1983)), where the reduced frequency is defined as

![]() $f^*=(\omega _k d_0)/(2\pi c_0)$

, in which

$f^*=(\omega _k d_0)/(2\pi c_0)$

, in which

![]() $d_0$

is the cascade pitch and equal to

$d_0$

is the cascade pitch and equal to

![]() $\pi (R_d+R_h)/V$

in the present model. The imaginary part is unified using the

$\pi (R_d+R_h)/V$

in the present model. The imaginary part is unified using the

![]() $\mathrm {e}^{-\mathrm {i}\omega t}$

time harmonic notation.

$\mathrm {e}^{-\mathrm {i}\omega t}$

time harmonic notation.

Figure 3. Resonance frequencies of rotating modes in a cascade of solidity

![]() $2.0$

, with varying circumferential mode number

$2.0$

, with varying circumferential mode number

![]() $m_0$

and different background mean flow Mach number

$m_0$

and different background mean flow Mach number

![]() $M=U/c_0$

. The reduced frequency is defined as

$M=U/c_0$

. The reduced frequency is defined as

![]() $f^*=(\omega _k d_0)/(2\pi c_0)$

, with

$f^*=(\omega _k d_0)/(2\pi c_0)$

, with

![]() $d_0 = \pi (R_d+R_h)/V$

. Frequency (a) real parts determine the fluctuation time periods and (b) imaginary parts indicate the growth rate of the resonance mode. At

$d_0 = \pi (R_d+R_h)/V$

. Frequency (a) real parts determine the fluctuation time periods and (b) imaginary parts indicate the growth rate of the resonance mode. At

![]() $m_0=V/2=24$

and

$m_0=V/2=24$

and

![]() $m_0=V=48$

the resonance modes reduce to the typical Parker’s stationary modes.

$m_0=V=48$

the resonance modes reduce to the typical Parker’s stationary modes.

3.1. General characteristics for rotating resonance frequencies

We then calculate for the resonance frequencies

![]() $\omega _k$

with continuously varying main mode order

$\omega _k$

with continuously varying main mode order

![]() $m_0$

(which corresponds to different inter-blade phase angle

$m_0$

(which corresponds to different inter-blade phase angle

![]() $\sigma$

), including both the rotational acoustic resonances and the stationary Parker modes. The same notations as in Koch (Reference Koch1983) are adopted in this section for the stationary Parker modes, where higher-order modes are denoted as

$\sigma$

), including both the rotational acoustic resonances and the stationary Parker modes. The same notations as in Koch (Reference Koch1983) are adopted in this section for the stationary Parker modes, where higher-order modes are denoted as

![]() $(q,0)$

(

$(q,0)$

(

![]() $|\sigma |=\pi$

) or

$|\sigma |=\pi$

) or

![]() $(q,1)$

(

$(q,1)$

(

![]() $|\sigma |=2\pi$

) modes, with

$|\sigma |=2\pi$

) modes, with

![]() $q$

denoting the axial order of the resonance. Note that an unstaggered stator cascade is studied such that the acoustic modes of positive and negative circumferential mode number

$q$

denoting the axial order of the resonance. Note that an unstaggered stator cascade is studied such that the acoustic modes of positive and negative circumferential mode number

![]() $m$

are symmetric to each other. Therefore, we only present results with positive

$m$

are symmetric to each other. Therefore, we only present results with positive

![]() $m_0$

, which are the same as for the

$m_0$

, which are the same as for the

![]() $-m_0$

resonance modes. Results with

$-m_0$

resonance modes. Results with

![]() $m_0$

up to

$m_0$

up to

![]() $m_0=V=48$

under different background flow speed are shown in figure 3, using the same geometry set-up as above and a fixed chord-to-pitch ratio (solidity) of 2.0. The resonance frequencies

$m_0=V=48$

under different background flow speed are shown in figure 3, using the same geometry set-up as above and a fixed chord-to-pitch ratio (solidity) of 2.0. The resonance frequencies

![]() $\omega _k$

are normalised following the same approach as in Koch (Reference Koch1983) and the reduced frequency is defined as

$\omega _k$

are normalised following the same approach as in Koch (Reference Koch1983) and the reduced frequency is defined as

![]() $f^*=(\omega _k d_0)/(2\pi c_0)$

, where the pitch at mid-radius

$f^*=(\omega _k d_0)/(2\pi c_0)$

, where the pitch at mid-radius

![]() $R_m=(R_d+R_h)/2$

is

$R_m=(R_d+R_h)/2$

is

![]() $d_0=\pi (R_d+R_h)/V$

.

$d_0=\pi (R_d+R_h)/V$

.

The real parts of resonance frequencies

![]() $\omega _k$

show rather organised distributions over certain branches beginning at

$\omega _k$

show rather organised distributions over certain branches beginning at

![]() $m_0=V/2=24$

or

$m_0=V/2=24$

or

![]() $m_0=V=48$

. At all branches, the oscillation frequency

$m_0=V=48$

. At all branches, the oscillation frequency

![]() ${\rm Re}(\omega _k)$

initiates from that of the classic stationary Parker modes and monotonically decreases with

${\rm Re}(\omega _k)$

initiates from that of the classic stationary Parker modes and monotonically decreases with

![]() $m_0$

, eventually approaching the cut-off frequency

$m_0$

, eventually approaching the cut-off frequency

![]() $\varOmega$

(Tyler & Sofrin Reference Tyler and Sofrin1962). Therefore, we may define each resonance branch as ‘

$\varOmega$

(Tyler & Sofrin Reference Tyler and Sofrin1962). Therefore, we may define each resonance branch as ‘

![]() $\mathrm {x}$

-type resonances’, named after the stationary modes they start from, as shown in the legend of figure 3.

$\mathrm {x}$

-type resonances’, named after the stationary modes they start from, as shown in the legend of figure 3.

Similar to the stationary mode results in figure 2, as the background mean flow Mach number

![]() $M$

increases, the cut-off frequencies of the duct modes will reduce, and the real parts of all resonance characteristic frequencies at different

$M$

increases, the cut-off frequencies of the duct modes will reduce, and the real parts of all resonance characteristic frequencies at different

![]() $m_0$

decrease. The negative imaginary parts of the characteristic frequencies, however, show different trends between the modes with

$m_0$

decrease. The negative imaginary parts of the characteristic frequencies, however, show different trends between the modes with

![]() $0\lt m_0\le V/2$

and

$0\lt m_0\le V/2$

and

![]() $V/2\lt m_0\le V$

. For modes with

$V/2\lt m_0\le V$

. For modes with

![]() $0\lt m_0\le V/2$

,

$0\lt m_0\le V/2$

,

![]() ${\rm Im}(\omega _k)$

decreases as

${\rm Im}(\omega _k)$

decreases as

![]() $M$

increases. For modes with

$M$

increases. For modes with

![]() $V/2\lt m_0\le V$

,

$V/2\lt m_0\le V$

,

![]() ${\rm Im}(\omega _k)$

does not necessarily decrease with higher background flow speed. The increase in the absolute value of the growth rate

${\rm Im}(\omega _k)$

does not necessarily decrease with higher background flow speed. The increase in the absolute value of the growth rate

![]() $|{\rm Im}(\omega _k)|$

indicates that more energy dissipation occurs for the resonance modes. The detailed mechanisms behind the variations in the inherent dissipation are discussed later.

$|{\rm Im}(\omega _k)|$

indicates that more energy dissipation occurs for the resonance modes. The detailed mechanisms behind the variations in the inherent dissipation are discussed later.

As the background flow speed increases, the number of the rotating resonance modes of each resonance branch also augments, and the left bound of each branch approaches an even lower circumferential mode order

![]() $m_0$

(as, for example, indicated by the black arrow at the top-right corner in figure 3). Note also that at each resonance branch, the difference between two neighbouring

$m_0$

(as, for example, indicated by the black arrow at the top-right corner in figure 3). Note also that at each resonance branch, the difference between two neighbouring

![]() ${\rm Re}(\omega _k)$

will gradually reduce as

${\rm Re}(\omega _k)$

will gradually reduce as

![]() $m_0$

increases. But if we just look at a few modes with continuously varying circumferential mode number

$m_0$

increases. But if we just look at a few modes with continuously varying circumferential mode number

![]() $m_0$

, the corresponding oscillation frequencies

$m_0$

, the corresponding oscillation frequencies

![]() ${\rm Re}(\omega _k)$

may show a nearly constant interval with a slight decrease as

${\rm Re}(\omega _k)$

may show a nearly constant interval with a slight decrease as

![]() $m_0$

increases. This characteristic is in agreement with the previous experimental results for practical axial compressor cascades (Parker Reference Parker1968; Camp Reference Camp1999; Holzinger et al. Reference Holzinger, Wartzek, Schiffer, Leichtfuss and Nestle2015).

$m_0$

increases. This characteristic is in agreement with the previous experimental results for practical axial compressor cascades (Parker Reference Parker1968; Camp Reference Camp1999; Holzinger et al. Reference Holzinger, Wartzek, Schiffer, Leichtfuss and Nestle2015).

3.2. Mode amplitude distributions of acoustic resonances

Physically, each characteristic frequency

![]() $\omega _k$

should correspond to a resonance state with a specific pressure distribution pattern; hence we may assume that at each

$\omega _k$

should correspond to a resonance state with a specific pressure distribution pattern; hence we may assume that at each

![]() $\omega _k$

the coefficient matrix

$\omega _k$

the coefficient matrix

![]() $\unicode{x1D653}(\omega _k)$

of order

$\unicode{x1D653}(\omega _k)$

of order

![]() $2(2M+1)N$

has a rank of

$2(2M+1)N$

has a rank of

![]() $2(2M+1)N-1$

. The basic solution of the outgoing wave mode amplitudes at each resonance state can be obtained with the procedure as follows. The upstream amplitude coefficient of the first radial mode at main circumferential mode order

$2(2M+1)N-1$

. The basic solution of the outgoing wave mode amplitudes at each resonance state can be obtained with the procedure as follows. The upstream amplitude coefficient of the first radial mode at main circumferential mode order

![]() $m_0$

is set as 1, i.e.

$m_0$

is set as 1, i.e.

![]() $A^K_{m_0 0}=1$

. The other mode amplitude coefficients are solved using the least-squares method with a pseudo-inverse matrix. To do so, equation (2.19) with zero right-hand side is rearranged into an overdetermined equation system, where the opposite of the column vector in

$A^K_{m_0 0}=1$

. The other mode amplitude coefficients are solved using the least-squares method with a pseudo-inverse matrix. To do so, equation (2.19) with zero right-hand side is rearranged into an overdetermined equation system, where the opposite of the column vector in

![]() $\unicode{x1D653}(\omega _k)$

relating to coefficient

$\unicode{x1D653}(\omega _k)$

relating to coefficient

![]() $A^K_{m_0 0}$

is moved to the right-hand side. As a result, we can directly compare the relative strength between the basic duct mode

$A^K_{m_0 0}$

is moved to the right-hand side. As a result, we can directly compare the relative strength between the basic duct mode

![]() $m_0$

and its inevitable higher-circumferential-order scattered modes, and further reveal the mode scattering effect by the cascade at resonance states. These are rarely seen in previous theoretical investigations. This procedure also helps to further classify the resonance states calculated with the SVD method by identifying the dominant acoustic mode with the largest amplitude, because due to aliasing, one inter-blade phase angle

$m_0$

and its inevitable higher-circumferential-order scattered modes, and further reveal the mode scattering effect by the cascade at resonance states. These are rarely seen in previous theoretical investigations. This procedure also helps to further classify the resonance states calculated with the SVD method by identifying the dominant acoustic mode with the largest amplitude, because due to aliasing, one inter-blade phase angle

![]() $\sigma$

can correspond to multiple solutions of characteristic frequency

$\sigma$

can correspond to multiple solutions of characteristic frequency

![]() $\omega _k$

with different dominant circumferential mode number

$\omega _k$

with different dominant circumferential mode number

![]() $m_0$

.

$m_0$

.

By generalising the definition of spin ratio in thermo-acoustic studies (Worth & Dawson Reference Worth and Dawson2017), we define two amplitude ratios between the amplitude coefficients of the scattered duct modes at

![]() $m_1=m_0-V$

,

$m_1=m_0-V$

,

![]() $m_2=m_0-2V$

and that at the main circumferential mode

$m_2=m_0-2V$

and that at the main circumferential mode

![]() $m_0$

:

$m_0$

:

This helps to describe the relationship between the main acoustic mode at resonance and its circumferentially scattered harmonic modes. As an example, the results for

![]() $\alpha$

-,

$\alpha$

-,

![]() $\beta$

-,

$\beta$

-,

![]() $\gamma$

- and

$\gamma$

- and

![]() $\delta$

-type modes at

$\delta$

-type modes at

![]() $M=0.2$

and

$M=0.2$

and

![]() $M=0.5$

are illustrated in figure 4, corresponding to a low-speed situation and a high-speed compressible flow situation, respectively.

$M=0.5$

are illustrated in figure 4, corresponding to a low-speed situation and a high-speed compressible flow situation, respectively.

Figure 4. Amplitude ratios AR1 and AR2 (see (3.2)) for (a) upstream-propagating waves and (b) downstream-propagating waves.

For

![]() $\alpha$

- and

$\alpha$

- and

![]() $\beta$

-type modes, AR1 reflects the relative magnitude between the dominant mode

$\beta$

-type modes, AR1 reflects the relative magnitude between the dominant mode

![]() $m_0$

and its major counter-rotating scattered mode

$m_0$

and its major counter-rotating scattered mode

![]() $m_1$

. At

$m_1$

. At

![]() $m_0=V/2=24$

, AR1 reduces to the original definition of spin ratio such that

$m_0=V/2=24$

, AR1 reduces to the original definition of spin ratio such that

![]() $\mathrm {AR1}=0$

means the resonance is a stationary mode with

$\mathrm {AR1}=0$

means the resonance is a stationary mode with

![]() $|A_{m_0 0}|=|A_{-m_0 0}|$

. Contrarily, AR2 only compares the magnitude of mode

$|A_{m_0 0}|=|A_{-m_0 0}|$

. Contrarily, AR2 only compares the magnitude of mode

![]() $m_0$

to its higher-circumferential-order scattered mode and indicates the relative strength of the dominant duct mode at resonance. As

$m_0$

to its higher-circumferential-order scattered mode and indicates the relative strength of the dominant duct mode at resonance. As

![]() $m_0$

reduces from

$m_0$

reduces from

![]() $V/2$

, AR1 increases monotonically from 0 approaching 1, demonstrating that the acoustic resonance gradually changes from a stationary mode to a rotating structure with increasing rotation characteristics. For all rotating resonances, a counter-rotating secondary scattered mode

$V/2$

, AR1 increases monotonically from 0 approaching 1, demonstrating that the acoustic resonance gradually changes from a stationary mode to a rotating structure with increasing rotation characteristics. For all rotating resonances, a counter-rotating secondary scattered mode

![]() $m_1=m_0-V$

always exists, and the strength of this counter-rotating mode gradually reduces as

$m_1=m_0-V$

always exists, and the strength of this counter-rotating mode gradually reduces as

![]() $m_0$

decreases. This finite-amplitude counter-rotating scattered mode might explain the phenomenon observed experimentally by Parker (Reference Parker1968), where he discovered that at resonance there existed both circumferentially forward- and backward-travelling acoustic waves, violating the precise circumferential mode number measurement. In addition, the increase of AR2 also with the reduction in

$m_0$

decreases. This finite-amplitude counter-rotating scattered mode might explain the phenomenon observed experimentally by Parker (Reference Parker1968), where he discovered that at resonance there existed both circumferentially forward- and backward-travelling acoustic waves, violating the precise circumferential mode number measurement. In addition, the increase of AR2 also with the reduction in

![]() $m_0$

shows a decreased relative strength for the higher-circumferential-order scattered modes at smaller

$m_0$

shows a decreased relative strength for the higher-circumferential-order scattered modes at smaller

![]() $m_0$

.

$m_0$

.

For

![]() $\delta$

- and

$\delta$

- and

![]() $\gamma$

-type modes, however, AR2 indicates the relative magnitude between the dominant mode

$\gamma$

-type modes, however, AR2 indicates the relative magnitude between the dominant mode

![]() $m_0$

and its major counter-rotating scattered mode

$m_0$

and its major counter-rotating scattered mode

![]() $m_2$

. In addition,

$m_2$

. In addition,

![]() $m_1=m_0-V$

is now a scattered duct mode with smaller circumferential mode number and is always cut-on. This cut-on scattered mode results in additional acoustic energy loss (additional dissipation for the resonance system) through axial wave propagation, and the resonance mode is thus no longer fully trapped in the cascade. This explains the reason for omitting these modes in the studies by Duan & McIver (Reference Duan and McIver2004).

$m_1=m_0-V$

is now a scattered duct mode with smaller circumferential mode number and is always cut-on. This cut-on scattered mode results in additional acoustic energy loss (additional dissipation for the resonance system) through axial wave propagation, and the resonance mode is thus no longer fully trapped in the cascade. This explains the reason for omitting these modes in the studies by Duan & McIver (Reference Duan and McIver2004).

However, things are different with non-zero background mean flow. Energy dissipation due to the unsteady vortex shedding at the cascade trailing edges and the steady–unsteady flow energy exchange (Howe Reference Howe1980; Rienstra Reference Rienstra1981, Reference Rienstra1984, Reference Rienstra2022) will always occur, such that all single-cascade resonance modes have an inherent negative growth rate as shown in figure 3. This indicates that acoustic resonances cannot exist without additional excitation sources. In aero-engine cascades, aerodynamic sources may have high circumferential mode order and oscillation frequency close to that of the resonance modes, and may possibly excite the nearly trapped rotating resonances with

![]() $V/2\lt m_0 \le V$

. The variation of the dissipation rate

$V/2\lt m_0 \le V$

. The variation of the dissipation rate

![]() $|{\rm Im}(\omega _k)|$

with

$|{\rm Im}(\omega _k)|$

with

![]() $m_0$

for rotating resonance modes at

$m_0$

for rotating resonance modes at

![]() $V/2\lt m_0\le V$

does not show a monotonic trend as in the case for

$V/2\lt m_0\le V$

does not show a monotonic trend as in the case for

![]() $\alpha$

- and

$\alpha$

- and

![]() $\beta$

-type modes. Note that the amplitude of the cut-on

$\beta$

-type modes. Note that the amplitude of the cut-on

![]() $m_1=0$

mode is actually zero at the stationary mode case where

$m_1=0$

mode is actually zero at the stationary mode case where

![]() $m_0=V$

. As

$m_0=V$

. As

![]() $m_0$

decreases from

$m_0$

decreases from

![]() $m_0=V$

, the magnitude of the cut-on scattered mode

$m_0=V$

, the magnitude of the cut-on scattered mode

![]() $m_1$

generally increases until

$m_1$

generally increases until

![]() $m_0$

gets too close to

$m_0$

gets too close to

![]() $m_0=V/2$

, as indicated by the decrease of AR1 in figure 4.

$m_0=V/2$

, as indicated by the decrease of AR1 in figure 4.

In general, the amplitude ratios of the upstream-propagating waves and downstream-propagating waves show similar trends and are of comparable shapes in figure 4. With an increased background flow speed, the main rotating resonance duct mode becomes slightly less dominant compared with its counter-rotating scattered mode. Ratio AR2 of

![]() $\alpha$

- and

$\alpha$

- and

![]() $\beta$

-type modes also slightly decreases, indicating a stronger higher-order scattering effect with a higher background mean flow Mach number

$\beta$

-type modes also slightly decreases, indicating a stronger higher-order scattering effect with a higher background mean flow Mach number

![]() $M$

. Results also confirm that resonances with an inter-blade phase angle of

$M$

. Results also confirm that resonances with an inter-blade phase angle of

![]() $\mp \pi$

and

$\mp \pi$

and

![]() $\mp 2\pi$

(the classic Parker modes) always correspond to purely stationary resonance modes. As the main circumferential mode number

$\mp 2\pi$

(the classic Parker modes) always correspond to purely stationary resonance modes. As the main circumferential mode number

![]() $m_0$