In his influential book Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, Michel Chion coined the phrase ‘materialising sound indices’ (Reference Chion and Gorbman1994, 114–17) as a means of describing aspects of a sound that draw direct attention to the physical nature of its source and the concrete conditions of its emission. Chion contrasted examples of footstep sounds that consist entirely of inconspicuous clicking with sounds that provide the feeling of texture (leather, cloth, crunching gravel). On a sliding scale, an abundance of materializing effects can pull a film scene towards the physical, or their sparsity can lead to a perception of narrative and character as abstract. Chion also argued that many Western musical traditions are defined by the absence of materializing effects:

The musician’s or singer’s goal is to purify the voice or instrument sound of all noises of breathing, scratching, or any other adventitious friction or vibration linked to producing the musical tone. Even if she takes care to conserve at least an exquisite hint of materiality and noise in the release of the sound, the musician’s effort lies in detaching the latter from its causality.

The conceptual framework for Chion’s argument can, of course, be traced back to Roland Barthes’s essay ‘The Grain of the Voice’ (Reference Barthes and Heath1977, 179–89), which examined the split between the voice and language. There are clear similarities between Barthes’s notion of the phenosong and genosong and Chion’s sliding scale of materializing sound indices. Both writers identified how technical prowess and expressive force in much musical performance irons out the workings of the physicality of production. Indeed, this seems an entirely appropriate description of the vast majority of mainstream orchestral film music where instrumental recordings strive for effortless clarity and perfect evenness; microphones are carefully placed to avoid scratchy or breathy sounds, intonation is always precise. How, then, might an audience be encouraged to feel the material conditions of a sound’s source in film scores, and what could that approach bring to the cinematic experience?

Outside of mainstream Western soundtrack production there are many types of music that explore precisely these issues: certain genres of contemporary classical music or experimental electronic music such as glitch, which employs deliberate digital artefacts, immediately spring to mind. Indeed, in the digital age materiality is often foregrounded in music that is heavily technologically mediated (Demers Reference Demers2010; Hainge Reference Hainge2013; Hegarty Reference Hegarty2007), particularly where noise is a centralizing concept. In many non-Western cultures instrumental materiality is also often celebrated and sounds proudly reveal their physical origin. The buzzy quality that is described by the Japanese concept of sawari is a pertinent example (Takemitsu Reference Takemitsu1995, 64; Wierzbicki Reference Wierzbicki2010, 198).

The apparent lack of materializing effects in mainstream soundtrack production is, unsurprisingly, also reflected in existing audiovisual scholarship: music and sound have been somewhat sidelined in discussions of sensuous materiality (Sobchack Reference Sobchack1992, Reference Sobchack2004; L. U. Marks Reference Marks2000, Reference Marks2002; Barker Reference Barker2009). When ideas about physicality and materiality do exist they tend to be confined to discussions about sound design or electronically generated music (Coulthard Reference Coulthard and Vernallis2013; Connor Reference Connor and Richardson2013). In this chapter I explore how musical noise in instrumental music is tied to material causality and announces its hapticity, creating an embodied connection with the audio-viewer. Some musical gestures powerfully recall the human motor actions that produce them, revealing the tactile physicality of their source. Some musical materials directly encourage sensation and enact the body. What does it mean to ‘grasp’ or be touched by a sound?

I will examine this issue through two examples that highlight different attitudes towards materialized film music. Jonny Greenwood’s score for Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (2007) consistently draws attention to its own physical materiality with textures – like the oil at the heart of the film’s narrative – that seem to issue from the very ground itself, a space that I argue is embodied by and through the music. The score celebrates haptic ‘dirtiness’ with the use of microtones, clusters and aleatoric and extended instrumental techniques. Greenwood is best known as the guitarist in the band Radiohead and not as a traditional film composer. I will argue that it was his position as a film-music outsider, coupled with Anderson’s independent filmmaking spirit and unconventional working practices, that allowed an embodied, dirty and haptic music aesthetic to be created in There Will Be Blood. The incorporation of a range of pre-existing pieces, including selections from Greenwood’s score for Simon Pummell’s film Bodysong (2003), and his orchestral works Smear (2004) and Popcorn Superhet Receiver (Reference Greenwood2005), are central to this attitude. But this is not the whole story.

On Anderson’s and Greenwood’s next collaborative film project, The Master (2012), there was a softening of the connection between materiality and causality. The noisy rupture that made There Will Be Blood such an extraordinary visceral experience had not entirely disappeared, but it had become somewhat sanitized. It is tempting to suggest that this shift occurred because Greenwood had learned to become more of a ‘film composer’, resulting in greater security in both the compositional and collaborative approach. This resonates with debates about the political and ideological implications of noise as most forcefully proposed by Jacques Attali (Reference Attali1985). Undesired or undesirable noise is understood as politically resistant, serving to disrupt the existing normative conditions and bring about a change in the system.

The score for There Will Be Blood, then, arguably represented something of an emerging new direction in contemporary film scoring that was both a reaction to the tight formatting of mainstream Hollywood films and an expression of the dirty media soundscapes of modern life. The score for The Master could be seen to have become assimilated into the mainstream cinematic language as a less resistant version of its former aesthetic self. Of course, it is not quite as simple as this. I also argue that the difference in approach reflects a standard Cartesian separation between the mind and the body, which is tied to the central narrative concerns of each film. The scores for There Will Be Blood and The Master respectively focus more on the body and the mind, exploring the boundaries between materiality that does not think and mentality that does not have extension in physical space. They represent the fluidity of contemporary film-scoring practice, demonstrating why Chion’s sliding scale of materializing sound indices is both useful and timely. By locating Chion’s materializing effects within phenomenological perception, we are able to reevaluate the impact of film-scoring traditions and consider previously undervalued aspects of soundtrack production.

Haptic Music

Studies of the haptic qualities of cinema have frequently argued that touch is not just skin deep but is experienced in both the surface and depths of the body. By dismantling binary demarcations of externality and internality, phenomenologists have highlighted the intimacy of cinema’s immersive connection to the human body rather than the distance created by observation. Hapticity does not refer simply to physical contact but rather to a mode of perception and expression through which the body is enacted. It describes our experience of sensation, how we feel the cinematic world we see and hear. As Vivian Sobchak argued, ‘the film experience is meaningful not to the side of our bodies, but because of our bodies’ with the result that movies can provoke in us the ‘carnal thoughts that ground and inform more conscious analysis’ (Reference Sobchack2004, 60; emphasis in original). For Jennifer Barker, ‘tension, balance, energy, inertia, languor, velocity, rhythm’ are all cinematic aspects that can be considered tactile, ‘though none manifests itself solely, or even primarily, at the surface of the body’ (Reference Barker2009, 2). Despite these broad and multivalent sensational aspirations, however, existing studies have been heavily biased towards the visual. Laura Marks’s concept of ‘haptic visuality’ (Reference Marks2002, xiii) tacitly seems to write sound out of experience. The same could be said of some of the most important books in this field: The Address of the Eye (Sobchak Reference Sobchack1992), The Skin of the Film (L. U. Marks Reference Marks2000) and The Tactile Eye (Barker Reference Barker2009). Admittedly, ‘The Address of the Ears’ or ‘The Ears of the Film’ do not make quite such punchy titles, but if we are interested in multisensory experience in order to ‘see the seeing as well as the seen, hear the hearing as well as the heard, and feel the movement as well as see the moved’ (Sobchack Reference Sobchack1992, 10), then there appears to have been a curiously superficial engagement with the sonic. As if to acknowledge this lack, Sobchak has more recently explored concepts of ‘ultra-hearing’ and ‘ultra-seeing’ (Reference Sobchack2005, 2) in Dolby Digital promotional trailers, although this does remain a rather isolated study.

The central claim I hope to advance is that in haptic film music the ears function like the organs of touch. In fact, more than this, I do not hear solely with my ears, I hear with my whole body. The ears are the main organs of hearing, but not the only ones. Total deafness does not occur since some hearing is achieved through bone conduction. Certain kinds of film music, particularly where there is a high degree of materialized sound, encourage or even demand a more embodied relationship with the audio-viewer. This is partly because of a mimetic connection to what is heard, a coupling of the body with the physical means of production of the sound itself. It is particularly true where instrumental music approximates noise, where materializing sound indices are more apparent. A clear definition of the ontology of noise is, of course, challenging, but here I adopt Greg Hainge’s five-point conception which ultimately suggests that ‘noise makes us attend to how things come to exist, how they come to stand or be (sistere) outside of themselves (ex-)’ (Reference Hainge2013, 23; emphasis in original). Hainge argued that noise resists, subsists, coexists, persists and obsists. He moved beyond the conception of noise as a subjective term by highlighting the ways in which it draws attention to its status as noise through material reconfiguration. Most usefully, he argued that there need not be a split between the operations of noise as a philosophical concept and its manifestations in expression; in other words, it is not necessary to separate the ontological from the phenomenological (Hainge Reference Hainge2013, 22).

Existing research has focused on how loud and/or low-frequency sounds permeate or even invade the body. In these cases, specific frequencies and amplitudes deliberately exploit the boundaries between hearing and feeling. Don Ihde explained that when listening to loud rock music, ‘the bass notes reverberate in my stomach’ (Reference Ihde2007, 44). Julian Henriques, likewise, demonstrated how low frequencies and extreme volume are deployed in the reggae dancehall sound system. Henriques argued that, in this musical culture, the visceral quality of the sound results in a hierarchical organization of the senses where sound blocks out rational processes. He described this process as sonic dominance, which

occurs when and where the sonic medium displaces the usual or normal dominance of the visual medium. With sonic dominance sound has the near monopoly of attention. The aural sensory modality becomes the sensory modality rather than one among others of seeing, smelling, touching and tasting.

Does sound need to be dominant for it to be experienced haptically? I would argue that haptic perception is still evident in works whose recourse to volume and amplitude is less clearly marked. My focus here is on something more subtle; music does not need to make my whole body shake or beat on my chest for me to feel it. Furthermore, in cinema the interconnecting relationships between sound and visuals do not typically rely on the obliteration of one medium by another: there is unity in the symbiotic creation of the haptic.

Lisa Coulthard’s exploration of haptic sound in European new extremism, which is in many ways a close relative of this study, explores low-frequency hums and drones in relation to silence. I wholeheartedly agree with Coulthard’s celebration of the corporeal: ‘The blurring of noise and music works to construct cinematic bodies that move beyond their filmic confines to settle in shadowed, resounding form in the body of the spectator’ (Reference Coulthard and Vernallis2013, 121). She perceives ‘dirtiness’ in the sonic imperfections offered by the expanded low-frequency ranges provided by digital exhibition technologies. I share the interest in the blurred boundaries between noise and music, but whereas Coulthard shows how sound both relies on and frustrates the quiet technologies of the digital, I explore how musical noise is tied to material causality and announces its hapticity. My aim, therefore, is partially to rehabilitate instrumental music within recent phenomenological discussions, which I see as an increasingly relevant and important aspect of soundtrack production. I also see this phenomenon as part of a broader aesthetic film-music tradition that reflects an inherent conflict between materialized and de-materialized music and, by extension, between the body and the mind. In seeking to reconcile these concepts, I want to move away from the most obvious physical experiences of loud and low-frequency music, to explore the caress as well as the slap, and to locate gradations of materialized sound.

Sound Affects: There Will Be Blood

There Will Be Blood is rich in haptic, visceral experiences. The oil we see and hear bubbling in the ground is like the blood coursing through the veins of the film, ready to erupt at any moment. In an early scene, following the first oil discovery, the camera lens is spattered with the black, viscous substance, threatening to splash through the membrane between the screen and audio-viewer. In celebration of the discovery a worker metaphorically baptizes his child by rubbing oil on his forehead. These two-dimensional visuals cannot break through the screen, but sound can. The adopted son of protagonist Daniel Plainview, H.W., loses his hearing following an explosion and the audience is sonically placed inside his body, experiencing the muffled and phased sound. We are literally invited to perceive the sound phenomenologically, not just hearing but feeling it in the body. We sense interiority and exteriority simultaneously, the environment within the experience of an other, but also outside it as an experience mediated by an other.

Additionally, Daniel Day Lewis’s vocal representation of Plainview is so rough and grainy that it almost seems as if there is sandpaper in his throat. One cannot hear this without a tightening of one’s own vocal cords. In a scene where the dubious church pastor, Eli Sunday, exorcizes a parishioner’s arthritis, he explains that God’s breath entered his body ‘and my stomach spoke in a whisper, not a shout’. The ensuing guttural appeal, ‘get out of here, ghost’, repeated by the entire congregation and becoming increasingly more strained, is chilling in the physical immediacy of its impact. Barthes’s phenosong is invoked in these vocalizations. The film constantly revels in aural textures that remind us of our own bodily existence and experience. There is much more that could be said about these and other sonic aspects of the film, but my focus here is on the music, which works on a more abstract, but nonetheless potent, level.

Matthew McDonald noted that Greenwood’s score is ‘exceptional for the overwhelming intensity established during the opening frames and returned to frequently throughout the film’ (Reference McDonald and Kalinak2012, 215). The music used is extracted from Part One of Greenwood’s Popcorn Superhet Receiver for string orchestra. The score explores clusters and quarter-tones in the manner of Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki, an enormous influence on Greenwood. The initial idea was to explore the concept of white noise created by two octaves of quarter-tones and to generate rhythmic material based on clusters, but the non-conformity of the individual players became more important to the composer as the piece developed:

I started to enjoy these ‘mistakes’: the small, individual variations amongst players that can make the same cluster sound different every time it’s played. So, much of the cluster-heavy material here is very quiet and relies on the individual player’s bow changes, or their slight inconsistencies in dynamics, to vary the colour of the chords – and so make illusionary melodies in amongst the fog of white noise.

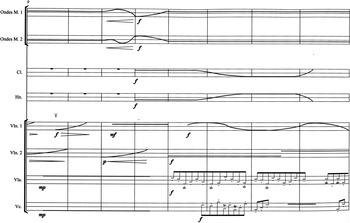

Indeed, a single stave is allocated to each of the violins (eighteen), violas (six) and cellos (six) throughout the piece. The four double-basses are divided across two staves. The individual variations or ‘mistakes’ exploited in the score celebrate the lack of uniformity in an orchestra. Following Alex Ross (see below), McDonald identified a string cluster becoming a contrary-motion glissando and moving towards and away from the pitch F♯ as a distinctive moment in the score (Example 10.1). This glissando is synchronized first with an exterior shot of mountains, subsequently with Plainview crawling out of a mine shaft having broken his leg, and much later in the film with shots of Plainview burying the body of an imposter he has murdered. McDonald argued that the music’s connotative function shifts ‘from the realm of setting to the realm of character’ and he moved towards the idea that the landscape and the individual are connected and inseparable, ‘a demonstration that the nature of the westerner is shaped by the nature of the West’ (Reference McDonald and Kalinak2012, 218).

Example 10.1 Score reduction/representation, Popcorn Superhet Receiver, bars 37–9.

I want to take this idea a stage further and suggest that it is the connection made between the film’s landscape – the metaphorical body of the film – the central character, Plainview, and our own embodied experience that are substantially shaped by the score and constitutes its extraordinary power. That fruitful tension has only been realized subconsciously by some commentators, who have, perhaps understandably, struggled to identify the elusive impact of the music that they find caught in a liminal space between the representation of landscape and the representation of character.

The recurrent glissando passage highlights friction. We feel the massed weight of bows on strings and left-hand tension on the fingerboard as the instrumentalists slide towards and away from the F♯ pitch centre. The sound moves from a ‘noisy’ state towards pitched ‘purity’ and then back again, bringing about the reconfiguration of matter that Hainge describes in his ontology of noise. Through this process we become aware of the physical nature of the sound source shifting between materialized and de-materialized effects. The materialized sound, the noisy, dirty music, makes its presence known, keeping us in a state of heightened tension. Friction and vibration are enacted in our bodies and embodied musical listening plays a significant role in our connection to both character and landscape in the film.

In his insightful review in the New Yorker (Reference Ross2008), Ross seems partially aware of his own bodily experience but is not fully prepared to make the connection. He argues that the glissandi ‘suggest liquid welling up from underground, the accompanying dissonances communicate a kind of interior, inanimate pain’. Whose pain, though? For Ross, this seems to be tied exclusively to character so that the ‘monomaniacal unison’ tells us about the ‘crushed soul of the future tycoon Daniel Plainview’. I suggest that this is also ‘pain’ that the audience is encouraged to feel through the soundtrack and it belongs as much to them as to environment or character. Ross’s presentation of a series of unresolved binary oppositions is most forcefully expressed in his understanding of the music as both ‘unearthly’ and the ‘music of the injured earth’. He gets closest to what I argue when he suggests that filmgoers might find themselves ‘falling into a claustrophobic trance’ when experiencing these sequences. All of this goes towards, but does not quite enunciate, the audience’s embodied connection. The simultaneous interiority and exteriority explains why the music is at once ‘terrifying and enrapturing, alien and intimate’.

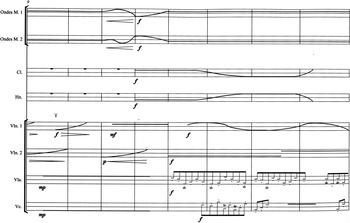

As I have been suggesting, the landscape in There Will Be Blood could be said to be metaphorically alive: the ground bleeds when it is ruptured, it groans and pulses through the use of sound design and music. Equally, Plainview could be seen to be emotionally dead, a walking cadaver, reduced to a series of bodily functions, motivated only by greed. Unsurprisingly, then, notions of burial, emergence, death and rebirth are central to the connection between the body and the land. In a scene in Little Boston, a worker in a mine shaft is accidentally killed by a drill bit that strikes him from above. As his mud-, oil- and blood-spattered body is removed from the shaft, the opening of Greenwood’s score for Smear (2004) is heard. Here the music emphasizes the space between pitches. The three-line staves in the graphic score (Example 10.2) represent a single whole-tone between concert G and A. Two ondes martenots, a clarinet, horn and string ensemble generate a constantly variable, insecure yet narrowly constrained texture. The fluctuating material is always in a state of becoming, never resting and never locating the pure tone. It is music in the cracks that highlights resistance to fixity, drawing attention to its own internal apparatus.

Example 10.2 Smear, bars 9–16.

The cue ‘Proven Lands’, which is derived from Part 2b of Popcorn Superhet Receiver, is heard when Plainview attempts to purchase William Bandy’s land in order to allow smooth passage for a pipeline. (The cue’s title, and those given below, are as they appear on the soundtrack album, Nonesuch 7559-79957-8.) Travelling with his imposter brother, Plainview undertakes a levelling survey and we are shown a series of breathtakingly beautiful landscape shots. The music, however, has a kinetic energy that belies the purely functional nature of the surveying task. The upper strings are required to strum rapid and relentless muted quaver pizzicati using guitar plectra, enhancing the clipped and percussive nature of the sound. The double-basses repeatedly slap the fingerboard and play pizzicato glissandi. The primary characteristic of this music is the dynamic exposure of the physicality of its source, the focus on human motor action. When we hear it, I suggest, the neuromuscular system is activated sympathetically. It generates motion, or the simulation of motion, within us. This concept reflects current research within neuroscience, particularly in relation to mirror neurones (for example, Mukamel et al. Reference Mukamel, Ekstrom, Kaplan, Iacoboni and Fried2010), which suggests that neurones are fired in the brain not only when humans act but also when they experience the same action performed by others. It is primarily an empathetic mode that may help us understand or make connections to others. An embodied mode of film scoring may, in turn, help us to engage directly with characters and/or narrative.

One of the film’s most striking cues follows a gusher blowout where a derrick is consumed in flames. The subsequent attempt to put out the fire, intercut with H. W.’s hearing loss (‘I can’t hear my voice’), is accompanied by a relentlessly visceral five-minute cue. The music is adapted from Greenwood’s track ‘Convergence’, which was originally composed for the film Bodysong. This documentary about human life, from birth to death, was constructed from clips of archive footage taken from more than one hundred years of film history. Given the direction of my argument, it hardly seems surprising that a film about the human body would generate music for use in There Will Be Blood. The piece is dominated by a recurrent anacrustic-downbeat combination played by the bass, a repetitive, punchy ‘boom boom … boom boom’ pattern. Over this, using the same simple rhythmic cell, various untuned percussion instruments generate polyrhythmic, chaotic clutter that constantly shifts in and out of phase. The recurrent patterns here, obviously, resemble a heartbeat, or multiple heartbeats, or perhaps also the mechanism of the drill in an emphatic organic/inorganic axis. Ben Winters (Reference Winters2008) noted the recurrent trope and importance of the heartbeat in film soundtracks, which he perceived as effective at helping us experience fictional fear in the context of own fear-inducing corporeality. In this sequence the score sets the heart racing and generates heightened and enacted excitement.

The intensity of the cue is further enhanced by some significant additions and modifications to the original ‘Convergence’ music. Greenwood superimposes the string orchestra, playing nervous, rapid figurations, clusters, and ‘noisy’ and ‘dirty’ textures. The low strings are especially materialized, generating growling glissandi, with aggressive bow strokes that slice, razor-like, through the frenzied texture. The bass pattern is enhanced digitally with beefed-up and distorted low frequencies enhancing the mimetic thumping, but as the camera tracks into a close-up of Plainview’s face towards the end of the sequence, the music is gradually filtered, reducing the high frequencies and making a more internal sound, the rhythm as felt inside the body. The relentless rhythmic drive in the scene is, therefore, narratively subsumed into Plainview’s body, but it is also by extension subsumed into our bodies as it mimetically regulates the heartbeat, another form of embodied interiority and connection. The incorporeal of Plainview’s screen body is enacted through the music in our bodies. This could partially explain the curious fascination with the odious character: when we observe Plainview we also experience a tiny part of ourselves.

The examples derived from Greenwood’s pre-existing scores demonstrate the importance of the role of the director and the music editor in the selection and use of aural materials. Greenwood also composed music specifically for the film, but did not write music directly to picture and instead provided a range of pieces that were spotted, edited and re-configured: ‘Only a couple of the parts were written for specific scenes. I was happier writing lots of music for the film/story, and having PTA [Paul Thomas Anderson] fit some of it to the film’ (Nonesuch Records 2007). Unlike most soundtrack composers, Greenwood found that he ‘had real luxury’ (Nialler9 2011) in not being expected to hit specific cue points or to write around dialogue. He was given free rein to write large amounts of music with specific scenes only vaguely in mind. This working approach seems to have resulted in several striking combinations of music and image. It is noteworthy, however, that the purely ‘original’ music for the film is much less materialized and more traditional in its construction (for example, cues such as ‘Open Spaces’ and ‘Prospector Arrives’).

The materiality in There Will Be Blood reflects the fluidity of the collaborative method, the clear directorial selection of musical materials and the relative inexperience of the composer, a potent mixture resulting in the disregard for certain scoring conventions and ‘rules’. The choices made by the director, editor and composer, especially in the use of pre-existing music and modified pre-existing music, contribute to a striking embodied experience. Writing in Rolling Stone, Peter Travis explained that the first time he saw the film he ‘felt gut-punched’ (Reference Travis2008). The instrumental music is fundamental in generating much of the hapticity that is a marker of the profound impact of the film and its score.

Incorporeality Regained: The Master

There are many surface similarities between There Will Be Blood and The Master. The films are both about pioneers, dysfunctional families, the roots of American modernity, manifestations of nihilism and conflicts between the evangelical and the entrepreneurial. They are both astonishing and detailed character studies. In The Master, the frontier landscape of There Will Be Blood is partially replaced by the sea. Musically, however, we appear to be in the same territory, but this is only initially the case. Greenwood’s pre-existing orchestral music is once again employed, and we hear two movements, ‘Baton Sparks’ and ‘Overtones’, from 48 Responses to Polymorphia (Reference Greenwood2011). This piece is a homage to Penderecki’s Polymorphia (1961), composed during his so-called sonoristic period, where the focus on textural sound masses and timbral morphology provided a new means of expression (Mirka Reference Mirka1997, Reference Mirka2000). It is prophetic that the composer of Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima (1960) is a shadowed presence in a film that opens on an island in the South Pacific on V-J Day 1945. We might, therefore, expect materiality to be centralized in the score for The Master. Yet, despite several initial glimpses of a visceral mode of scoring, this music soon gives way to something more ‘refined’.

The opening shot of the sea is accompanied by an aggressive, if brief, Bartókian string passage – the initial gestures from ‘Baton Sparks’ – but this soon recedes into a series of slow suspended harmonies reminiscent of Barber’s Adagio for Strings (1936). Images of demob-happy naval officers wrestling on a beach and the inappropriate actions of the sex-obsessed protagonist, Freddie Quell, contain the strongest indication of the embodied musical potential in the score. Col legno low strings and a jazz-inspired bass spring around a solo violin playing jerky and scratchy gestures. The score for The Master begins where There Will Be Blood left off, promising a materialized aesthetic, but this is not what is ultimately delivered.

As the story progresses, particularly after we have been introduced to Lancaster Dodd, the leader of a movement known as The Cause, the music takes on a bittersweet, ironic quality. For example, the music derived from ‘Overtones’, which is first heard at a wedding on board a boat, contains lush string movement based around white-note clusters and artificial harmonics. It is almost too sweet and cloying, perhaps suggesting that Dodd is not to be trusted. There is clearly still a degree of materiality in the construction of the score, with a characteristic use of indeterminacy (Example 10.3). Greenwood employs I.R.I. tremolos, which he describes as ‘Independent, Random and Intermittent notes added to a held pitch – like a fingered tremolo but with only occasional use of the second note’ (Reference Greenwood2011, 15). However, the music does not emphasize noise, rather it generates a beautiful, gossamer-like harmonic texture revolving around C major, which could easily float away in the sea air. In Hainge’s ontological taxonomy, the potentially ‘noisy’ elements in this construction do not challenge: they coexist harmoniously and centralize musicality rather than critiquing it. The potential ‘noise’ is not a by-product of expression but central to the expressive harmonic content. To be sure, this is not standard mainstream film-music fare either, but equally it does not focus the audio-viewer’s attention on material sensation as was the case in There Will Be Blood.

Example 10.3 ‘Overtones’ from 48 Responses to Polymorphia, bars 22–9, fluttery textures and bitter-sweet harmonies.

Significantly, the more heavily materialized sound-mass sections from 48 Responses to Polymorphia – such as the first half of ‘Overtones’ – the moments that resonate most closely with Pendercki’s sonoristic musical language, have not been deployed in The Master. It is the sections with fewer materializing effects, the pitch-biased and harmonically rich music, that are used to support narrative representation. The choices made by the director, editor and composer in the use of pre-existing music function in this score much more like traditional film music.

The same is true of a good deal of the music Greenwood composed specially for the film. In a scene where Freddie Quell finds himself on board the Master’s boat and begins to learn the methods of The Cause, the music employs impressionistic gestures and patterns as a reflection of the journey (‘Alethia’ on the soundtrack album, Nonesuch 532292–2). Quell is adrift metaphorically and physically: he listens to a recording of Dodd explaining how man is ‘not an animal’; he observes a regression therapy session; he attempts to attract the attention of a woman to whom he has never spoken by writing ‘do you want to fuck’ on a piece of paper and presenting it to her. The cue is entitled ‘Back Beyond’ and the chamber ensemble, featuring clarinet and harp, bears some resemblance in harmonic structure and orchestration to Ravel’s Introduction and Allegro (1905). The modal vacillation, blurred and layered harmony, and consistent use of arpeggios reflect the unpredictability of the sea and the aimless drifting of the protagonist. This music is concerned less with materiality than a series of harmonic extensions built above the D♭ home pitch. It leads to the moment when Dodd begins a series of disquieting psychological questions designed to unearth Quell’s past traumas.

Later, when Quell supports Dodd in promoting his new book, The Split Saber, the score features a series of suspended F♯ diminished-seventh chords resolving onto C♯ major. The homophonic yearning created by the intimate chamber ensemble could easily be located within the rich panoply of film music’s harmonic heritage. Towards the end of the film, Quell takes another boat journey, this time across the Atlantic, in order to be reunited briefly with Dodd. Here the E minor harmonies generate a traditional tonal hierarchy, with particular prominence given to the dominant seventh and its tonic resolution. This suggests greater clarity, perhaps some degree of finality on Quell’s part – an effective way to indicate character progression through harmonic development. It is music rich in expressive harmonic potential, but not rich in its use of materializing sound indices.

One way of reading this softening of the connection between materiality and causality is that Greenwood had learned to become a ‘proper’ film composer by the time he worked on The Master, following his experiences on Norwegian Wood (2010) and We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011). The experiments undertaken in There Will Be Blood became more refined, less resistant and thus assimilated into a mainstream system. If it takes an outsider to question the normative model, the successful outsider also eventually becomes part of the formatting of the new system. Tempting though it is to pursue this interpretation, it is only partially true. We have already seen how the decision to focus on materialized sound is frequently encapsulated in the pre-existing music of There Will Be Blood and is, therefore, closely tied to the decisions of the director and music editor. The Master’s pre-existent music is much less materialized. Indeed, voices from the past in the form of Ella Fitzgerald’s ‘Get thee Behind Me Satan’ (Irving Berlin, 1936), Helen Forrest’s ‘Changing Partners’ (Larry Coleman and Joe Darion, 1953) and Jo Stafford’s ‘No Other Love’ (Paul Weston and Bob Russell, 1950) suggest an important role for nostalgic reverie, rather than materialized sensation.

The distinction I attempt to articulate here may simply say as much about the narrative and aesthetic differences between the two films as anything else. This in turn affects the function and purpose of both scores. Whereas There Will Be Blood worked hard to make the audience feel each moment, The Master focuses on internal memory. Dodd’s methods centralize the idea of past-life regression, recalling memories from before birth, as a beneficial and healing process. Freddie is a veteran suffering from nostalgia. The film constantly delves into the past and into the recesses of the mind. Anderson has suggested that Quell could be understood as ‘a ghost’ (Hogan Reference Hogan2012), a man who is both dead and alive. Indeed, it could be argued that the soundtrack, much like Quell himself, is an apparition, an intangible construct of the mind. In There Will Be Blood, Plainview is also dead, in a way, but the music brings him purposefully to life through landscape. Conversely, in The Master Quell’s impulsive and animalistic acts of violence (such as strangling a customer in a department store or smashing a toilet in a jail cell) are never accompanied by any musical score.

If we accept the conceptual framework of Cartesian dualism, then the aesthetic positioning of the two scores reflects a shift of focus from the body to the mind. In Principles of Philosophy (1644), René Descartes gave the first systematic account of the interaction between the mind and body. He discriminated between mental and material ‘substances’, arguing that they were distinctive and excluded each other, but he also suggested that the body causally affected the mind and the mind causally affected the body. The two films centralize material substance and mental substance respectively, a move away from texture, form, location and weight towards images, emotions, beliefs and desires. Whereas the representation of the land and Plainview in There Will Be Blood emphasized material embodiment, Quell and Dodd in The Master reflect the ethereal workings of memory.

I do not wish to suggest for one moment that The Master does not contain effective film music, or that it lacks narrative engagement, simply that its materiality is not as foregrounded as in There Will Be Blood. Some hapticity in The Master may be located, as Claudia Gorbman has suggested (Reference Gorbman2015), in Philip Seymour Hoffman’s varied and virtuosic vocal representation of Lancaster Dodd. In any case, there is a clear difference in the material nature of the two film scores, which invites us to identify and understand distinct approaches to the use of materializing effects.

Conclusions

Chion’s materializing sound indices, though previously considered solely in relation to sound design, could be used to describe the aesthetic and embodied differences between the instrumental scores for There Will Be Blood and The Master. There Will Be Blood attempts to engage the audio-viewer by infiltrating the body as a means of reaching the mind. The Master, instead, focuses primarily on the mind as the main narrative space of the film, and constantly scrutinizes memory.

By aligning Chion’s theory with phenomenology, we are able to understand the contents of aural cinematic experience as they are lived, not as we have typically learned to conceive and describe them. Indeed, a sliding scale of materiality could be a useful tool in exploring a range of film scores. Within this context, we could argue that Greenwood is a more ‘material’ composer than many others. Yet, there are also distinctions in his methods and approaches based on narrative context, collaborative relationships, interactions with pre-existing music and so on.

This chapter has attempted to re-establish a connection between the haptic and the aural, so that our understanding of instrumental film scoring is no longer unnecessarily disembodied. A phenomenological approach could usefully re-materialize our objects of perception. Indeed, if we were to re-evaluate some significant moments in film-music history using this conceptual framework and sliding scale, we might more fully understand the extraordinary visceral impact of Bernard Herrmann’s score for Psycho (1960) or of John Williams’s for Jaws (1975). This is film music that remains powerful to this day, in no small part because of its embodied qualities. Noise need not be understood as a by-product of the filmmaking process, or as a danger to the integrity of the body, or as a force to be attenuated. Some film scores feature prominent materialized elements that directly attempt to stimulate the material layers of the human being. There are modes of instrumental scoring where there is an abundance of materializing sound indices and we can simultaneously feel as much as we hear.