Introduction

Background

For clinicians working in the prehospital setting, the analgesic management of moderate to severe pain can include opiates, such as morphine and fentanyl, or inhaled analgesics, such as nitrous oxide or methoioxyflurane.Reference Borland, Jacobs and Rogers1 More recently, however, various textbooksReference Nutbeam2 and guidelinesReference Chesters and Webb3-Reference Petz, Tyner and Barnard5 have recommended the use of ketamine in prehospital analgesia. These recommendations have been incorporated into clinical practice. For example, paramedics in New South Wales and Australia Capital Territory have a protocol for its analgesic use,Reference Hollis, Keene, Ardlie, Caldicott and Stapleton6 and the US Department of Defense (Virginia USA) has recommended the use of ketamine for prehospital use in battlefield analgesia.Reference Dickey7 Ketamine acts primarily as an N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, although it may have other mechanisms of action.Reference Jonkman, Dahan, van de Donk, Aarts, Niesters and van Velzen8 The NMDA receptor is a ligand gated channel for the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate, antagonism, of which produces its analgesic effect.

Ketamine has been posited to be an attractive choice in the prehospital setting for several reasons. Firstly, the drug has favorable pharmacokinetics – a rapid onset, short duration, titratable dose, and large therapeutic window, all of which make it an appealing option with a relatively low-risk profile.Reference Buckland, Crowe and Cash9 This is particularly true in resource-limited settings,Reference Dickey7,Reference Mercer10 where the large therapeutic window allows for management of greater numbers of patients where there may be limited access to full patient monitoring. Further, ketamine has favorable pharmacodynamic properties in the absence of shock. Although a direct cardiorespiratory depressant, by releasing endogenous catecholamines, there is maintenance of cardiovascular stability and respirationReference Bion11 and maintaining pharyngeal reflexes to ensure airway patency.Reference Scheppke, Braghiroli, Shalaby and Chait12 In addition to its analgesic benefits, other prehospital uses include sedation of violent or anxious patients,Reference Scheppke, Braghiroli, Shalaby and Chait12,Reference Schultz13 procedural sedation,Reference Chesters and Webb3,Reference Bredmose, Lockey, Grier, Watts and Davies14 and rapid sequence intubation.

Importance

While the safety of ketamine as an analgesic is well-established for use in the emergency department,Reference Lee and Lee15-Reference Sener, Eken, Schultz, Serinken and Ozsarac18 acute post-surgical,Reference Jonkman, Dahan, van de Donk, Aarts, Niesters and van Velzen8 and cancer pain,Reference Bredlau, Thakur, Korones and Dworkin19 the evidence is less clear in the prehospital setting.Reference Borland, Jacobs and Rogers1,Reference Gausche-Hill, Brown and Oliver20 A 2011 reviewReference Jennings, Cameron and Bernard21 found a paucity of evidence on this issue with few well-designed clinical trials, and was unable to support or refute the use of ketamine within the prehospital context. However, since 2011, more studies have been published investigating the efficacy and safety of ketamine as a prehospital analgesic.

Goals of the Investigation

Therefore, the aim of this study was to review whether, in patients requiring prehospital analgesia, the use of ketamine results in satisfactory pain relief, and to compare this to other analgesic agents. The secondary aim was to quantify the incidence and types of adverse effects and complications from the use of ketamine.

Research Question

Participants—Studies of adult patients (aged over 21 years) who received ketamine for the primary purpose of pain reduction in the prehospital setting were included. Prehospital analgesia is defined as any analgesia that is given to a patient in an ambulance or retrieval team on-site or during transport to a hospital.

Intervention—The intervention consisted of the administration of ketamine. No restrictions were set for the route of administration, the administration of other medications concurrently, or the dosage. Studies in which ketamine was administered for indications other than analgesia were excluded.

Comparison—Any analgesic regimen for the reduction of prehospital pain without the concurrent administration of ketamine was used for comparison.

Outcomes—The primary outcome of interest in this study was quantitative measurements of reduction in severity of pain, OR a quantitative measurement on the degree of pain relief from ketamine. Studies which provided qualitative or expert opinions on adequate pain relief were not included. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of adverse events, its sedative effect, as well as the specifics of the administration of ketamine.

Study Design—Given the paucity of high-level, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) within this setting, it was decided a priori to include all study types. Overall, this gave a collection of randomized and non-randomized trials, cohort studies, case control studies, retrospective case studies, and case series in which ketamine was used as a prehospital analgesic.

Methods

Search Strategy

This systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42018094562), and subsequently, a review of the literature was conducted using several electronic medical literature databases. A search of AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database; Health Care Information Service of the British Library; London UK; 1985 - September 2018); Medline (US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland USA); SCOPUS (Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands); Web of Science (Thomson Reuters; New York, New York USA); Cochrane (The Cochrane Collaboration; London, United Kingdom); and EMBASE (Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands) databases (1970-September 2018) was performed. Medical Subject Headings (MESH) were used to focus the search, and a range of keywords were used, as shown in Table 1, to ensure inclusion of all relevant articles, with only literature published in English, or those which could be translated to English, included. Back and forward referencing of the included studies were also hand searched to identify any further, relevant articles. A grey literature search of Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (Bielefeld University Library; Bielefeld, Germany), Open Grey (INIST-CNRS - Institut de l’Information Scientifique et Technique; Paris, France), and nongovernmental organization (NGO) search, as well as a review of relevant emergency, anesthetic, and prehospital conference papers and abstracts, was also conducted to identify further articles. No individual authors were contacted.

Table 1. Keyword and Medical Subject Headings (MESH) Used for the Literature Search

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The titles and abstracts of identified articles were independently evaluated by two reviewers (AB and EW) for inclusion based on their relevance and adherence to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included all articles relevant to the question that could be translated to English, that involved human subjects, and that were based in the prehospital setting. Populations of adults and all study types were allowed. Exclusion criteria were studies in which ketamine was used for another indication (ie, sedation of violent or anxious patient or rapid sequence intubation), if there was no quantitative measurement specifically for level of pain, or if ketamine was administered in the emergency setting rather than a prehospital one. Any disagreements in included studies after full-title and abstract review were discussed and negotiated between the two reviewers until a consensus was reached. Subsequent to this, a pilot data extraction of 20% of the papers included after full-text review was undertaken by two reviewers, which showed a strong kappa agreement (k = 0.82). Subsequently, the rest of the data extraction was undertaken by one reviewer (AB).

Evaluation of Articles

In order to assess the strength of the evidence in individual studies, two independent reviewers analyzed the bias using the validated SIGN 50 methodological assessment tool,Reference Harbour and Miller22 which utilizes a checklist of criteria that have a significant effect on bias to assess and score the bias as either high-quality (++), acceptable (+), or low-quality (-), as well as grading the evidence based on study type: RCTs being Grade I, case control or cohort studies being Grade II, and non-analytical opinions such as case reports and case studies being Grade III (Table 2). Expert opinions are Grade IV, but were excluded from the systematic review due to its inclusion-exclusion criteria. Any disagreements on strength of evidence ratings were discussed and negotiated between the two reviewers until a consensus was reached.

Table 2. SIGN50 guidelines for evaluation of evidence grading of articles

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

The significant heterogeneity in study design, analgesic regimens, and pain assessment meant that a meta-analysis could not be appropriately performed, and a qualitative synthesis of the papers in each subgroup was made using the GRADE hierarchy of recommendations,Reference Piryani, Dhungana, Piryani and Sharma Neupane23 in which grades evidence on a scale from A-D from high to very low level of evidence.

Results

Overall, the search identified 767 references, with 707 unique papers. Of these references, 668 were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Of the 42 articles that were short listed for full-text review, a total of 10 were identified as meeting all the criteria, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram of Publication Assessment for Study Inclusion.

Studies fell into one of three groups based on their study design:

1. One-arm studies evaluating only ketamine in the prehospital setting, without comparator group;

2. Multi-arm studies comparing ketamine to other analgesics, or no analgesic, in the prehospital setting; or

3. Multi-arm studies comparing the analgesic efficacy of the co-administration of ketamine and morphine with morphine alone in the prehospital setting.

Group 1: Studies Evaluating Only Ketamine in the Prehospital Setting without a Comparison Group

A total of nine studies either retrospectively or prospectively observed the analgesic efficacy and safety of ketamine in the prehospital setting, the majority of which were case series. The metric for assessing analgesia was unspecified in five of these studies,Reference Bredmose, Grier, Davies and Lockey24-Reference Wedmore, Johnson, Czarnik and Hendrix28 and not a specific scale of analgesia in another,Reference Husum, Gilbert, Wisborg, Van Heng and Murad29 and so were excluded. Three studies used the numerical rating scale, and all stated that ketamine provided safe and adequate analgesia, with very few observed or recorded side effects listed within the studies (Table 3Reference Fisher, Rippee, Shehan, Conklin and Mabry30-Reference Johansson, Sjöberg, Nordgren, Sandström, Sjöberg and Zetterström32). There was, however, marked heterogeneity in both the sample sizes (from nineReference Fisher, Rippee, Shehan, Conklin and Mabry30 to 585Reference Husum, Gilbert, Wisborg, Van Heng and Murad29) and populations investigated, from tertiary center prehospital retrivalsReference Bredmose, Grier, Davies and Lockey24 to soldiers in military settings.Reference Husum, Gilbert, Wisborg, Van Heng and Murad29

Table 3. Studies Evaluating Only Ketamine in the Prehospital Setting without a Comparison Group

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; EMS, Emergency Medical Services; IM, intramuscular; IN, intranasal; IV, intravenous.

Overall Recommendation: There is low (Grade C) evidence supporting the analgesic efficacy and safety of ketamine in the prehospital setting.

Group 2: Studies Comparing Ketamine to Other Analgesics, or No Analgesics, in the Prehospital Setting

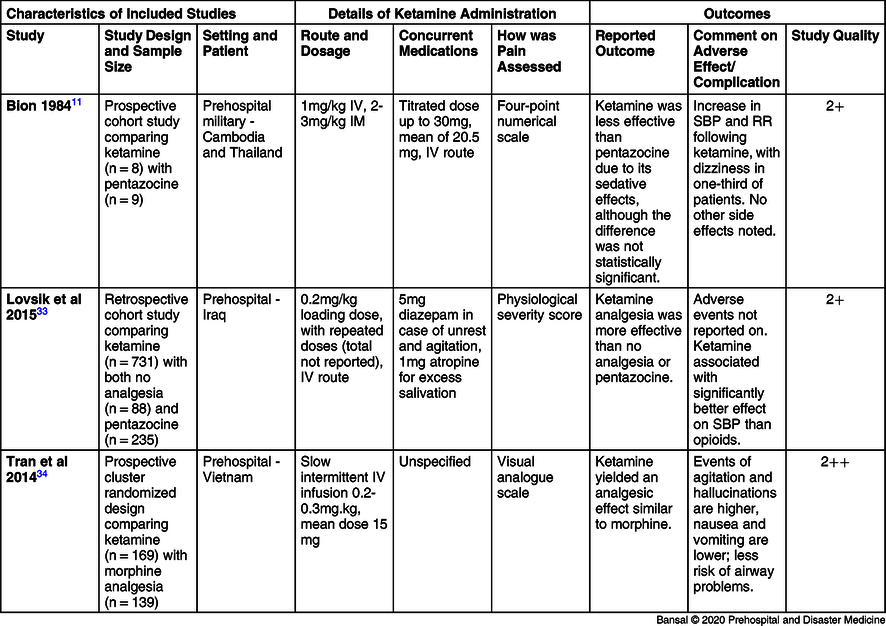

No RCTs were found. Three prospective observational studies were identified that made a comparison between ketamine and other prehospital analgesic options (all opioids), as shown in Table 4.Reference Bion11,Reference Losvik, Murad, Skjerve and Husum33,Reference Tran, Nguyen and Truong34 Two compared ketamine with pentazocine (an opioid), one with morphine, and one with no analgesia. Two of these studies had three arms to include a no analgesia option. One of these was a prospective clutter randomized study. All studies used either a numerical rating scale or visual analogue scale to measure effectiveness. Two of the three reported ketamine to be equally or more effective than opioid analgesia (morphine, pentazocine, or fentanyl), with one paper from 1984 finding it to be less effective. Again, there was marked heterogeneity between the studies with small study sizes, and the dosage of ketamine ranging from a median of 15mg to 77mg.

Table 4. Studies Comparing Ketamine to Other Analgesics, or No Analgesics, in the Prehospital Setting

Abbreviations: IM, intramuscular; IN, intranasal; IV, intravenous; RR, respiratory rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Overall recommendation: There is low (Grade C) evidence that ketamine was at least as effective as opioids as a prehospital analgesic agent.

Group 3: Studies Comparing the Analgesic Efficacy of the Co-Administration of Ketamine and Morphine with Morphine Alone in the Prehospital Setting

An overall of four studies evaluated the pain relief offered by morphine alone compared with morphine and ketamine, as shown in Table 5.Reference Galinski, Dolveck and Combes35-Reference Wiel, Zitouni and Assez38 Three studies were RCTs. One RCTs reported no difference in pain relief, but a reduction in morphine requirements; one RCT reported a reduction in pain alone; and one RCT compared a ketamine infusion with placebo after both study arms had received a morphine bolus, and reported no difference in pain relief. One study investigated the impact of co-administration on morphine requirement, finding that it was lower when ketamine was given.

Table 5. Studies Comparing the Analgesic Efficacy of the Co-Administration of Ketamine and Morphine with Morphine Alone in the Prehospital Setting.

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate; IM, intramuscular; IN, intranasal; IV, intravenous; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RR, respiratory rate.

Overall Recommendation: There is moderate (Grade B) evidence that co-administration of ketamine with morphine lead to equal or greater pain reduction, as well as reducing morphine requirement.

Discussion

This systematic review set out to update the evidence of ketamine as a prehospital analgesia, given the appearance of more publications on this topic since the most recent systematic review. Overall, the main findings of this paper are that, in comparing the effectiveness of using ketamine or opioids as the sole prehospital analgesic, there is low-grade evidence that ketamine is equivalent with, or slightly superior to, opioid analgesia. Further, there is moderate evidence that the co-administration of ketamine with morphine in the prehospital setting may improve analgesic effectiveness and reduce of morphine requirement. Finally, the studies support a low incidence of a cardio-respiratory depressant effects of ketamine, although the small sample sizes in most of the studies mean they may have been under-powered to detect effects.

The findings of this review may have implications for advice to clinical practice. For example, the Australian College of Pain Medicine (Melbourne, VIC, Australia) places ketamine as a prehospital analgesic as Level 2 evidence according to National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC; Canberra, Australia) guidelines,39,40 based on their analysis of Jennings, etal’s 2011 review.Reference Jennings, Cameron and Bernard21 Given the presence of new randomized trialsReference Tran, Nguyen and Truong34,Reference Jennings, Cameron and Bernard36,Reference Wiel, Zitouni and Assez38 and more cohort studies and case seriesReference Fisher, Rippee, Shehan, Conklin and Mabry30-Reference Losvik, Murad, Skjerve and Husum33,Reference Shackelford, Fowler and Schultz41 since 2011, consideration could be given to reconsider this. For example, this review reports low-grade evidence that ketamine is a safe and effective analgesic option on its own, and only low-grade evidence that it is at least as effective as opioids or fentanyl. However, with regard to the co-administration of ketamine with morphine, there is moderate evidence that it may lead to equal or greater pain reduction, as well as lower morphine requirement.

This paper has identified three areas that have implications for future research. First, several studies were excluded as they did not offer clear methodology on how ketamine’s analgesic effectiveness was evaluated. Resource limitation in prehospital medicine, as well as the fact that ketamine is often the preferred option in the hemodynamically unstable patient,Reference Häske, Böttiger and Bouillon42 may account for the lack of documented pain intensity and adverse event monitoring. The lack of standardized measurement of outcomes does mean that a meta-analysis could not be appropriately performed. It would be beneficial if future studies incorporated standardized measures of pain assessment, such as a numerical scale or visual analogue scale.

Second, due to the small sample size of a number of these studies, it is possible that they are under-powered to detect rare adverse events. The variability in sample sizes of included studies were such that adverse events occurring with an upper 95% confidence interval rate from 1%-38% (estimated using the rule of threesReference Jovanovic and Levy43). However, any study with a sample size less than 50 (six of the 10 included studies) could only detect adverse events occurring in over five percent of the sample. While there do exist reports of frequent adverse events following prehospital administration, for example a case series of 13 patients that reported three cases of hypoxia, one of laryngospasm, and five episodes of emergence phenomenon,Reference Burnett, Salzman, Griffith, Kroeger and Frascone44 these patients were given a high ketamine for chemical restraint. Analgesic doses of ketamine should produce less frequent, but no less important, adverse events. A common hesitation with the use of ketamine in the prehospital setting is a concern about its side effects –emergence phenomenon, dissociation, transient apnea, and increased salivary secretions leading to laryngospasm.Reference Marland, Ellerton and Andolfatto16 Measuring and reporting of undesirable effects of ketamine analgesia is therefore important, not only to quantifying the range and frequency of potential side effects, but also to allow them to be managed and mitigated. For example, awareness of the presence of emergence phenomenon after ketamine administration means that it is often co-administered with midazolam (as it was in seven of the 10 included studies), which can reduce the rate of emergence phenomena by two-thirds.Reference Perumal, Adhimoolam, Selvaraj, Lazarus and Mohammed45

Finally, it may be useful to investigate the long-term benefits, side effects, and complications of ketamine. This review was only able to identify two papers that looked at the emergency department admission or long-term (six-month follow-up) effects of prehospital ketamine administration. Jennings, etalReference Jennings, Cameron and Bernard46 investigated the long-term effects of ketamine versus morphine use in a prehospital setting, finding that in the long term, there was no difference in prevalence or persistent pain or health-related quality of life six months after injury.

Limitations

This review was limited by a relatively small number of studies included, few of which were randomized controlled studies. In addition, there were few studies where ketamine was used either as the primary analgesic (which would have allowed a direct measurement of its analgesic efficiency) or where is was compared head-to-head with another analgesic agent, in particular an opioid. The review was also limited to studies published in English.

Conclusion

The administration of safe, effective analgesia in the prehospital environment is imperative.Reference Shackelford, Fowler and Schultz41,Reference McGhee, Maani, Garza, Gaylord and Black47 Ketamine, with its favorable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, is an extremely attractive option in a wide variety of settings. This study, by reviewing the current literature on ketamine as a prehospital analgesic, found only low-quality evidence to support the use of ketamine as a single- or first-line analgesic. There is, however, moderate evidence for the co-administration of ketamine with morphine as a safe and effective prehospital analgesic option that may also reduce opioid requirement. There is insufficient power in the included studies to adequately address the short- and long-term safety of ketamine, which should be further studied.

Conflicts of interest

None to declare.

Author Contributions

AB conducted the literature search, extraction, and constructed the results and discussion section. MM, IF, and BB all refined the research question, discussion, and reviewed the paper.