The era of the German Lied stretched approximately from the mid-eighteenth to the early twentieth century. It flowered most richly during the nineteenth century, chiefly in the hands of four leading composers: Franz Schubert (1797–1828), Robert Schumann (1810–1856), Johannes Brahms (1833–1897), and Hugo Wolf (1860–1903). Altogether they produced more than a thousand songs, from which the core Lied repertoire is drawn today.1 These men were fine pianists although none was a singer of their own material except in the loosest sense.2 This chapter focuses on figures who were both composers and performers of their own material, in other words, possible precedents for a modern conception of the singer-songwriter. Their activity has often been overlooked because the concept of the public song recital was in its infancy for the greater part of the nineteenth century, so while most singers sang songs within mixed programmes, none could earn a living exclusively in this way and most participated in a thriving salon culture.3 Many were women, who benefited from the opportunities for musical training which emerged in the late eighteenth century. In comparison, professional pianists or even conductors, as in Schumann’s case, had clearer routes to establishing a professional identity. Indeed, from the very outset, the piano was integral to Lied performance. Therefore although the term ‘Lied singer-songwriter’ is used throughout this chapter, the implication is always, in fact, Lied singer-pianist-songwriter. This chapter traces the history of Lied singer-songwriters in three stages: a consideration of Schubert’s predecessors and contemporaries (c. 1760–1830), Schubert’s followers (c. 1830–48), and finally, contemporaries of Brahms and Wolf (c. 1850–1914).

Broadly speaking, the Lied evolved from a technically undemanding type of music largely aimed at amateur (often female) singers, to a genre which eventually dominated professional recital stages in 1920s Berlin.4 Various interlinked factors contributed to this shift: the rise of institutionalised musical training; the concomitant emergence of the idea of a ‘recital’; and the astronomical growth of the music publishing industry, which made sheet music for every conceivable technical standard available to the public.5 Songwriters worked in an ever more complex environment which coexisted with (but did not fully supplant) the original, amateur, private nature of the genre.

The years 1820–48 were arguably the golden age of the Lied singer-songwriter, since the genre had matured in Schubert’s hands, whilst the keyboard writing was still usually within the reach of a keen amateur. From the mid-century onwards, many instances of the genre were so pianistically demanding that singers without the requisite keyboard skills could only hope to compose simpler, folk song derived types that persisted throughout the century. While Lied singer-songwriters were almost inevitably superb singers themselves, the compositional emphasis upon the accompaniment grew.6 As musical training grew more specialised, multi-skilled musicians became increasingly rare. Nowadays, there is not a single professional Lieder singer who would consider accompanying themselves onstage, and only a few would have the keyboard skills to accompany themselves in private.

Schubert’s predecessors and contemporaries

The work of a number of early Lied singer-songwriters includes examples of two coexisting, but discrete, influences: the virtuosic Italian sacred and stage music which dominated the courts and public performance spaces of the Holy Roman Empire; and the new, transparent, folk-styled German Lied which emerged in response to the literary and philosophical theories of Johann Christoph Gottsched (1700–1766) in the 1730s.7 Gottsched’s contemporary, the tenor Carl Heinrich Graun (1703/4–59), exemplifies this split. A professional tenor at the court of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Graun composed the simplest of Lieder alongside his Italian opera, court and church music. His songs appeared in various compilations from 1737 onwards. The ‘Ode’ below, drawn from the posthumously published compilation Auserlesene Oden zum Singen beym Clavier (1764) is a typical example.

Example 2.1 Graun, Auserlesene Oden zum Singen beym Clavier (1764), vol. 1, no. 7, ‘Ode’, bars 1–6.

The singer and composer Johann Adam Hiller (1728–1804) is now mainly remembered for his operas. Hiller greatly admired his predecessor Graun, and like him, was proficient in the techniques and styles of Italian opera.8 By his own admission, in the 1750s his tastes drew him increasingly towards the ‘light and singable, as opposed to the difficult and laborious’.9 Hiller’s importance in the development of German musical culture lies not only in his composition of songs, but also in his commitment to raising the standard of public concert singing:

It has always been a concern of mine to improve the state of concert singing. Previously this important task had been regarded too much as a lesser occupation, and there was no other singer except when one of the violists or violinists came forward, and with a screechy falsetto voice … attempted to sing an aria which, for good measure, he could not read properly.10

Hiller was involved with the subscription concerts of the Grosse Concert-Gesellschaft in Leipzig, and also founded his own singing school, which embraced general musicianship, choral and solo singing.11 Crucially, he supported the training of women, and several female singer-songwriters of the next generation studied with him, including Corona Schröter (1751–1802), discussed further below, and Gertrud Elisabeth Schmeling (later Mara) (1749–1833). Hiller drew his pedagogical aims into his songwriting, thus aria-like works sit alongside simple folk-style tunes in his collections. These include the Lieder mit Melodien (1759 & 1772), Lieder für Kinder (1769), Sammlung der Lieder aus dem Kinderfreunde (1782), and 32 songs in the Melodien zum Mildheimischen Liederbuch (1799).

The great Lied scholar Max Friedlaender (1852–1934) argued that this was the point at which the German Lied became truly independent of foreign models.12 Hiller’s generation of songwriters consisted of a mixture of amateurs and professionals, singers, composers, poets, collectors and editors. Their activity acquired huge ideological and political significance in Germany following Johann Gottfried von Herder’s coining of the term ‘folk song’ (‘Volkslied’) in the 1770s: this would define the distinct cultural identity of ‘Germany’, a country which did not yet exist except in the imagination of its peoples.13 By the early nineteenth century, building on Herder’s ideas, writers like the Schlegel and Grimm brothers regarded folk song as a ‘spontaneous expression of the collective Volksseele (or folk soul)’.14 This new manifestation of German identity had to be accessible, in keeping with the way that lyric poetry was developing; indeed, poetry and music were so closely wedded that the term Lied applied equally to poems as to songs. The poetry often consisted of ‘two or four stanzas of identical form, each containing either four lines of alternating rhymes or rhymes at the end of the second and fourth lines only’.15 The melodies were often short and memorable, supported by the barest of accompaniments. Importantly, the prevailing aesthetic of simplicity meant that the singing and composition of the Lied was not limited to technically skilled professionals as, say, the composition of operas and symphonies might be. This ideology persisted well into the next century, endorsed by influential figures such as the writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) and the song composers Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814) and Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758–1832). Melody remained paramount; the accompaniment would ideally provide just harmonic support, ‘so that the melody can stand independently of it’.16 It is therefore unsurprising that some of Goethe’s amateur associates in his home town of Weimar were more prolific Lieder composers than many professional musicians.17 Alongside its political weight, the Lied was also the symbol of culture in the upper classes, evidence of Bildung or self-cultivation.

The Lied was also considered respectable for women in a way that opera could never be. Goethe’s friend Corona Schröter was a beneficiary of Hiller’s belief that women should have access to musical education. A singer, actress, composer and teacher, Schröter published two Lieder collections in 1786 and 1794, prefacing the first set with an announcement in Cramer’s Magazin der Musik: ‘I have had to overcome much hesitation before I seriously made the decision to publish a collection of short poems that I have provided with melodies … The work of any lady … can indeed arouse a degree of pity in the eyes of some experts.’18 A sense of her compositional style can be seen in Example 2.2. Schröter was also an important voice and drama teacher. She was awarded a lifelong stipend for her singing by the Duchess Anna Amalia of Weimar and her voice was praised by both Goethe and Reichardt.19 Despite her close association with Goethe (she acted in and composed incidental music to his play Die Fischerin of 1782), her compositions are hardly known.20

Example 2.2 Schröter, ‘Amor und Bacchus’ (published 1786), bars 1–12.

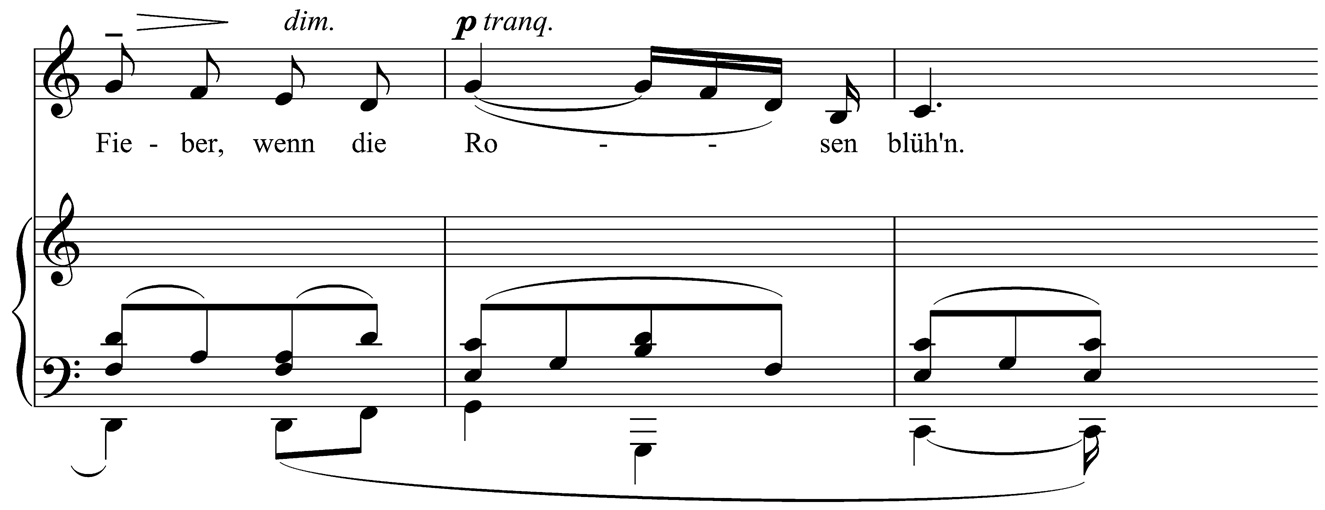

In an age when the two leading songwriters, Zelter and Reichardt, were not singers of their own songs, it is figures like Schröter who emerge as central. Two other women who, unlike Schröter, had no access to formal musical education but benefited from their cultivated home environments, were Luise Reichardt (1779–1826) and Emilie Zumsteeg (1796–1857). Reichardt was the daughter of Johann Friedrich Reichardt. She gleaned her musical knowledge from the illustrious company which frequently met in her father’s home in Giebichenstein near Halle, for whom she regularly sang. These figures included the leading lights of German literary Romanticism such as the Grimm brothers, Ludwig Tieck, Novalis (Friedrich von Hardenberg), Joseph von Eichendorff, Clemens Brentano, and Ludwig Achim von Arnim. Luise Reichardt was a remarkable woman. She moved to Hamburg in 1809 while her father was still alive, supporting herself as a singing teacher and composer. Additionally, she played a central role in bringing Handel’s choral works to wider attention, translating texts and preparing choruses for performances which were then conducted by her male colleagues. Although her compositional achievements were overshadowed by her father’s, she wrote more than seventy-five songs and choruses, many of which became extremely popular. Some of her songs were published under her father’s name in 12 Deutsche Lieder (1800). Luise Reichardt’s ‘Hoffnung’ (see Example 2.3) was so popular that it endured well into the twentieth century in arrangements for small and large vocal ensembles, particularly in English translation under the title ‘When the Roses Bloom’.

Example 2.3 Luise Reichardt, ‘Hoffnung’, bars 1–18.

Reichardt’s contemporary Emilie Zumsteeg was also the daughter of one of the most successful songwriters of the day, Johann Rudolf Zumsteeg (1760–1802), who lived in Stuttgart. Emilie Zumsteeg had a fine alto voice and developed a substantial career as a pianist, singer, composer and teacher.21 Like Luise Reichardt, Emilie Zumsteeg’s social circle included many leading poets of the day, which stimulated her interest in the Lied. She wrote around sixty songs, and her Op. 6 Lieder were praised in the national press. Almost a century later, they were still singled out for their rejection of Italian vocal style: ‘After this modish Italian entertainment music, it does us much good to get acquainted with the simple, straightforward and intimately sung German songs of Emilie Zumsteeg.’22 The quality of Zumsteeg’s voice was reflected in the relative adventurousness of her compositions; the same reviewer also observed that the first and third song of the set required a larger vocal range than usual.

Bettina von Arnim (1785–1859) presents a very different model of Lied singer-songwriter from the professionally independent Reichardt, Schröter, and Zumsteeg. The sister of one great poet, Clemens Brentano, and the wife of another, Ludwig Achim von Arnim, she too existed in a highly cultivated literary circle that encouraged a text-centred conception of the Lied. Although she composed roughly eighty songs, most of these are fragments, since her true strength lay in improvisation. Von Arnim ‘constantly struggled to commit her ideas to paper and permanence’.23 Only nine songs were published in her lifetime.24

The Westphalian poetess Annette von Droste-Hülshoff (1797–1848) was one of a significant number of nineteenth-century writers who composed settings of their own and others poets’ verses. These settings tended to follow transparent folk song models, reflecting the original ideological underpinning of the Lied as poetry/music for the people. Similar songs by the poets Hoffmann von Fallersleben and Franz Kugler were absorbed into German folk culture and reproduced anonymously in anthologies throughout the century.25 Von Fallersleben in particular popularised his songs through his own performances. The children’s songs he composed remain popular nursery rhymes in Germany today, while his patriotic songs are still sung by male-voice choirs.

Von Droste’s musical activity was more in keeping with her cultivated and aristocratic background in Westphalia. Music was practised at a high standard at home and was complemented by frequent visits to the theatre and concerts. Her letters reveal her to have been a great admirer of keyboard improvisation, when it was well done, and this is also evident in her songs.26 She was a highly competent pianist; one letter to a friend recounts the events of a concert in which she was to participate with another singer: ‘Finally, when the concert was about to begin, Herr Becker, who was to accompany us, declared that he couldn’t do it and that I, therefore, would have to play the piano myself … well, it went fine and we were greatly applauded.’27

Von Droste’s composition was further stimulated by her growing interest in collecting folk songs (through the influence of her brother-in-law, the antiquary Johann von Lassberg). As a result, she made an arrangement of the Lochamer Liederbuch, one of the most important surviving collections of fifteenth-century German song, in c. 1836. Her uncle, Maximilian Friedrich von Droste-Hülshoff (1764–1840), also gave her a copy of his 1821 guide to thoroughbass, entitled Eine Erklärung über den Generalbass und die Tonsetzkunst überhaupt. Drawing together these various influences, she made settings of her own poetry and verses by leading writers such as Goethe, Byron, and Brentano. None were published in her lifetime.

Women singer-songwriters generally came from well-to-do, cultivated families which offered creative stimulus through an educated social circle – essential in the absence of widespread opportunities for formal training. While gifted Italian women could gain an outstanding musical education, this was not the case in Germany.28 Barred from most public activity, the Lied offered women an arena in which they could be creative without transcending the limitations imposed by societal mores. In other words, women, as well as men, could compose songs, but the professional status of ‘composer’ was deemed appropriate only for men. The nature of the genre fixed it in the home, a space in which women could perform their own compositions without attracting criticism. Following the work of Hiller, Schröter, Zumsteeg and others, education for women flourished. The idea of the Lied as private entertainment and edification was increasingly embraced by a ‘bourgeoisie now prosperous and ambitious enough to want to imitate the sophisticated leisure of the upper classes’.29

Most importantly, from the 1810s onwards, Schubert exploded the limits of the genre by revolutionising the piano accompaniments, and fusing a German sensibility with the richness of Italian vocal music (thanks to the influence of his teacher, the distinguished composer Antonio Salieri (1750–1825)). The tenor Johann Michael Vogl (1768–1840) was thirty years older than Schubert, but their collaboration was to bring about the ‘professionalisation’ of Lieder-singing. The ‘German bard’s’ memorable performances of Schubert’s songs with the composer himself at the piano were widely celebrated.30 Like Schubert himself, Vogl initially trained as a chorister.31 His own compositions included masses, duets, operatic scenes and, of course, Lieder.32 As an aside, Vogl’s two published volumes of songs evince a range of influences from cosmopolitan Vienna: the folk-like German Lied and his professional background as an operatic singer. As a result, while his songs are generally quite straightforward, they are not formulaic (see Example 2.4).

Example 2.4 Vogl, ‘Die Erd’ ist, ach! so gross und hehr’ (published 1798), bars 1–20.

Lied singer-songwriters after Schubert

Despite the transformations effected by Schubert, the political and ideological urge to resist the evolution of the Lied was very much alive. In 1837, long after Schubert’s death, the Lied was defined in Ignaz Jeitteles’ Ästhetisches Lexikon as possessing: ‘easily grasped, simple, undemanding melody, singable by the amateur; a short or at least not lengthy lyric poem with serious or comic content; the melody of the Lied should only exceptionally exceed an octave in compass, all difficult intervals, roulades and ornaments be avoided, because simplicity is its main characteristic.’33 Such a definition could just as easily have been penned half a century earlier. At the same time, public song performance was burgeoning, culminating in the baritone Julius Stockhausen’s performances of complete song-cycles by Schubert and Schumann in the mid-1850s and 1860s.34 Within this maelstrom of influences, the Lied could be anything from the simplest tonal melody accompanied by a few chords, to vocally and pianistically virtuosic songs for the concert stage. In this context, it is worth turning to two Viennese Lied singer-songwriters: Johann Vesque von Püttlingen and Benedict Randhartinger. Each represented a strand of song-making that has been largely forgotten, but was just as productive and popular as works by the masters of the genre.

The distinguished diplomat, jurist, musician and artist Johann Vesque von Püttlingen (1803–1883) was extremely well-connected. He participated in soirées with Schubert, Vogl, the composer Carl Loewe, and the playwright Franz Grillparzer. However he also socialised with composers of the next generation including Robert Schumann, Otto Nicolai, and Hector Berlioz. He even sang his own settings of the poetry of Heinrich Heine to Schumann, who liked them very much.35 Vesque exemplifies the thriving and unselfconscious culture of amateur song performance and composition in the nineteenth century. Like many figures of the Biedermeier period, he was astonishingly proficient in many diverse areas. He was skilled enough to take the tenor role in Schumann’s oratorio Das Paradies und die Peri at the Leipzig Gewandhaus when the singer due to perform had to cancel at short notice – a testament to just how porous the term ‘amateur’ was.36 Under the pseudonym ‘J. Hoven’ (which drew on the last two syllables of Beethoven’s revered name), he composed 300 songs, of which no fewer than 120 are settings of Heine. His 1851 song-cycle of Heine settings, Die Heimkehr, is, at 88 songs, the longest in musical history. After the revolutions of 1848, which were not only a political but also a cultural watershed in Austro-Germany, Vesque’s songs were dismissed as sentimental and old-fashioned. Nevertheless, many have innovative forms, exceptionally well-crafted melodies, and imaginative accompaniments. See, for instance, the rippling, watery texture he devised for the opening of ‘Der Seejungfern Gesang’ (The Song of the Damselfly) Op. 11 no. 2:

Example 2.5 Vesque, ‘Der Seejungfern Gesang’ Op. 11 no. 2, bars 1–6.

It has also been pointed out that Vesque anticipated some aspects of Wolf’s songs, particularly his flexible, speech-like setting of the German language.37 See, for example, Op. 81 no. 58 ‘Der deutsche Professor’:

Example 2.6 Vesque, ‘Der deutsche Professor’ Op. 81 no. 58, bars 1–15.

Vesque’s songs also testify to the quality of his voice. There is no doubt that he deserves to be better known as an exceptionally successful amateur singer-songwriter.

One further Viennese Lied singer-songwriter is the tenor Benedict Randhartinger (1802–1893). Like Schubert, he studied at the Wiener Stadtkonvikt and also with Salieri, before joining the Wiener Hofmusikkapelle. Alongside many other works, he wrote an astonishing four hundred songs, and was successful as a professional performer of his own works – a singer-songwriter in the truest sense, and one with the added lustre of having known Schubert and Beethoven personally.38 Indeed, he was so highly regarded that in 1827, he was ranked alongside Schubert and Franz Lachner as one of the ‘most popular Viennese composers’.39 Clara Schumann and Franz Liszt were among his accompanists.40 He had particular success with his dramatic ballads, a sub-genre of German song that gained enormous popularity through the century.

An important influence on Randhartinger was the north German tenor and composer, Carl Loewe (1796–1869). Loewe’s development as a singer-songwriter was shaped by a promise he made to his devout father, a Pietist cantor, not to write music for the stage; possibly as a result of this, he channelled his sense of the dramatic into his songs and ballads, some of which are nearly half an hour long and show some similarities to dramatic scena. He was also a highly successful composer of oratorios. For most of his life, Loewe was the civic music director in Stettin, the capital of Pomerania near the Baltic Sea. He taught at the secondary school during the week and supplied music for the local church on Sundays.41 However, during the summer holidays, particularly from 1835–47, he travelled and built his reputation as a performer of his own ballads. His performances were enjoyed in Mainz, Cologne, Leipzig, Dresden, Weimar, and Vienna, and further afield in France and Norway.42 In 1847 he even performed for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in London.43 Among his fans was Prussia’s crown prince, who later became King Friedrich Wilhelm IV.44

Loewe’s ballads have remained in the repertoire, but many are unprepossessing on the page. Randhartinger apparently preferred Schubert’s songs to Loewe’s because he found them more ‘singable’; it is possible that Randhartinger found the demanding vocal range of Loewe’s songs not to his taste.45 Nevertheless, as with Schubert, Loewe’s first opus from 1824 already marked him out as a songwriter of great imagination and distinction, as is seen from the drama of the vocal line and the detail of the shimmering, unearthly accompaniment in Example 2.7.

Example 2.7 Loewe, ‘Erlkönig’ Op. 1 no. 3, bars 1–14.

The rapid decline of Loewe’s tremendous popularity suggests that his own interpretation was central to the success of the music. His recitals had an intimacy that distinguished them from the public world of, say, the piano recital. There were never more than two hundred people in the audience. Given the small scale of this musical career, Loewe’s fame is all the more remarkable. For Schumann, Loewe was nothing less than a national treasure, who embodied a ‘German spirit’, a ‘rare combination of composer, singer and virtuoso in one person’.46

Lied Singer-Songwriters in Brahms’ and Wolf’s day

By the second half of the century, opportunities for singer-songwriters were shifting. On one hand, it was increasingly acceptable for women to have concert careers (if not operatic careers) after marriage. On the other hand, the Lied onstage had evolved well beyond the simple folk song, thereby excluding anyone who was not truly proficient on the piano.

The career of the teacher, composer, singer and pianist Josephine Lang (1815–1880) showed how the possibilities of publication for female Lied singer-songwriters had been transformed. The daughter of a noted violinist and an opera singer, Lang was a precociously talented pianist who composed her earliest songs when she was just thirteen years old.47 At fifteen she met Felix Mendelssohn, who listened to her performing her own Lieder, and he praised her talent warmly, calling her performances ‘the most perfect musical pleasure that had yet been granted to him’.48 Lang was to publish over thirty collections of songs during her lifetime, as well as gaining a considerable reputation as a singer at the Hofkapelle in Munich.49 Her circle of friends included Ferdinand Hiller, Franz Lachner, and Robert and Clara Schumann. She married the poet Christian Reinhold Köstlin in 1842; when he died in 1856, she supported herself and her six children through teaching. Lang, like Vesque, wrote songs which merit greater attention, as evinced by the opening of ‘Schon wieder bin ich fortgerissen’, published in 1867 (see Example 2.8).

Example 2.8 Lang, ‘Schon wieder bin ich fortgerissen’ Op. 38 [39] no. 3, bars 1–18.

Pauline Viardot-García (1821–1910) was a tremendously successful singer from a family of celebrated vocal performers. Sister of Maria Malibran and daughter of Manuel García, she enjoyed success on the operatic stage as well as the concert platform, and regularly appeared in London, Berlin, Dresden, Vienna and St Petersburg. A fluent speaker of Spanish, French, Italian, English, German and Russian, she composed vocal works in all of these languages (over a hundred items in all), and also added vocal parts to piano works by Chopin.50 Her Lieder include settings of poems by Eduard Mörike, Goethe and Ludwig Uhland, including her very first published song: a setting of Uhland’s Die Capelle which she produced at the request of Robert Schumann for inclusion in his journal, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, in 1838.51 As a cosmopolitan performer and composer, Viardot-Garcia’s contribution to the Lied is small but significant, given her close friendships with the Schumanns, Mendelssohn, Brahms and Wagner. She was also an influential vocal teacher.

In the last few decades of the nineteenth century, the Breslau-born George Henschel (1850–1934) emerged as an exceptionally gifted singer, pianist, conductor and composer who did much to promote the Lied in Germany, England and America. Henschel was a member of the Brahms circle and a protégé of the violinist Joseph Joachim and his wife, the contralto Amalie. The Joachims were keen to support Henschel’s career as a singer, and he appeared in many concerts alongside Amalie Joachim, who was a great proponent of the Lied in public concerts.52 Henschel later performed with Brahms in the mid-1870s; but by this stage, he was already accompanying himself in private gatherings.53 Following a hugely successful debut in London in 1877, he travelled to the United States in 1880 with his Boston-born fiancée, Lilian Bailey (1860–1901), who was also a singer. When the two gave their first Boston recital on 17 January 1881, Henschel took the role of singer and accompanist, playing for both himself and his bride-to-be.54

Henschel’s importance as a Lied performer was twofold. He was one of the first performers to give regular vocal recitals in which there were almost no non-vocal items – he turned away from the traditional ‘miscellany’ model of programming in order to put the song centre-stage.55 He also acted as the sole interpreter of his own compositions on many occasions, and both the accompaniments of his own pieces, and those of other songs he chose to perform, suggest that he was a prodigiously talented pianist. His numerous song compositions include twenty-five numbered opus sets for solo voice, several collections for duet and vocal quartet, choral works and an opera. Since he was popular with both English and German-speaking audiences, many of his Lieder were published with English translations, and he also composed many songs to English poems, such as Tennyson’s Break, Break, Break and texts from Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies.56 They range from straightforward parlour pieces, almost certainly intended for an informal setting, to more pianistically and vocally complex items, such as the ballad Jung Dietrich, Op. 45, published in c. 1890:

Example 2.9 Henschel, ‘Jung Dietrich’ Op. 45, bars 1–16.

The decline of the Lied is often dated to the outbreak of the First World War, with Richard Strauss’ Vier letzte Lieder of 1948 as its epilogue. As a result of Germany’s defeat, the growing international popularity of the genre was abruptly halted; within the nation, other changes took place which affected its fate. It should be stressed, however, that in the pre-war period, the Lied was more popular than ever.57 For this reason, it is more accurate to talk of a fragmentation of the Lied than a decline, and this was brought about by a range of social and musical factors. Firstly, the collective political impetus behind the Lied – the establishment of the German nation – was defused through Prussia’s victory in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1, which led to the establishment of a unified German nation. The narrowing of professional pathways, and the rise in complexity of both vocal and piano parts meant that the likelihood of finding a single performer capable of singing and playing the piano at a professional level had decreased. In connection with this technical elevation, composers sought to lift the ‘humble’ Lied to the perceived grander status of the symphony and opera, and thus were increasingly attracted by larger-scale, more complex variations of the genre such as the song-cycle and orchestral Lied. A significant aesthetic shift was initiated by Hugo Wolf, who reasserted the centrality of the poem, as Gottsched had proposed a century and a half earlier. It was Wolf’s practice to preface the performance of each of his songs with a recitation of the text; although this arguably restored its supremacy, it also put asunder words and music, which in the ablest of hands had fused so seamlessly. Furthermore, in order to give due attention to each inflection of a poem, Wolf’s musical realisations were musically and conceptually extremely demanding. Harmony in the age of Modernism – of which Wolf was an important precursor – also altered the relationship between melody and accompaniment, which had hitherto generally been intuitive and supportive.

The rejection of received musical models by the followers of Richard Wagner also led to a diversification of approaches to the Lied. Gustav Mahler integrated his songs into his symphonies; Arnold Schoenberg used his Lieder for small-scale experiments with radical harmony; and his pupil Hanns Eisler rejected this aesthetic entirely to write Hollywood-style songs in an attempt to reclaim the Lied’s ‘traditional location at the border between the popular and the serious’.58 The lack of a unified view of what the Lied should be served to render it too esoteric and practically complex to retain a place in live private music-making and contemporary popular culture. As jazz and light music took its place there, the development of recording technology offered the Lied a new home. While the Lied continues to live on the recital stage and in the recording studio, the singer-songwriters of the Lied exist no more.