My mother told me that there were ghosts of the dead, those that drowned in the ocean and if I went to the edge, they would pull me in…What I can remember is the fishing net dropped along the side of the huge boat. I thought surely, we would fall into the ocean and die at this moment of rescue. We were so exhausted, there was no energy left in me to climb. I could see the waves lashing their claws upon the boat and people above extending their arms towards us.Footnote 1

Journeys on oceans and seas that refugees and asylum seekers have taken under perilous conditions have received much media and public attention in recent times, but there has been limited scholarly focus on refugee ocean journeys as significant and complex events in histories of forced movement. Many accounts have described, rather than systematically analysed, the specific dimensions of the ocean, and therefore the multi-layered way the ocean has determined and shaped the fate of refugee boats and those travelling on them has remained under explored. Towards contributing to this scholarship with this distinctive perspective, this article adopts an interdisciplinary approach that – for the first time – integrates insights and frameworks from the methodologies of ocean engineering, historical archival research, and oral history.

One boat journey of escape and rescue from Vietnam in 1982 is the focal point of this research. The journey was arranged by an extended family group who decided that the only way to flee Vietnam under communist rule with their children was to have a boat built and disguise the escape as a fishing trip. To help fund the venture, they sold passages on the boat that were surplus to their family's needs. The boat departed Vũng Tàu, a town on a peninsula of Southern Vietnam, approximately 100 km south-east of Ho Chi Minh City, on the morning of 20 June 1982. It was expected that the boat would carry no more than forty people, but during the gruelling and secret processes of embarking, many more people wanting to escape forced themselves on board. The plan was for the boat to travel east towards the Philippines, with the understanding that when they were outside of national territorial boundaries they may be rescued by a commercial vessel. This plan did not come to fruition. The boat was caught in a storm, the engine failed during the journey, and those navigating realized that they did not know where they were going. On 23 June 1982, after three nights at sea, the boat was rescued in the South China Sea by Le Goëlo, a vessel on a humanitarian mission to assist escaping refugees, which had been organized by the French group Médecins du Monde (MdM). The boat rescued became known as the 101 Boat because there were 101 people on board who were all successfully transferred to the rescue vessel.Footnote 2

This particular rescue of refugees at sea is part of oceanic humanitarianism examined in this article. In this context, oceanic humanitarianism not only refers to rescue by human intervention such as that by the organization MdM. We consider the ocean itself as a humanitarian agent that significantly influenced the fate of the Vietnamese refugees on 101 Boat. Framed this way, we argue that the ocean as a humanitarian agent has the potential to either save the lives of refugees or destroy them. As we shall see, this could be understood in scientific and environmental terms taking into account the wind speed and direction, wave height, length, and frequency, or – in religious terms – as an act of God.

The opening quotation is a key memory by one of the authors of this article, Anh Nguyen Austen, who was five years old when she was part of the 101 Boat journey. Nguyen Austen conducted oral histories with the adults who planned the escape by boat, and her statement highlights the personal and emotional insights that people's recollections can provide. For example, memories of bodily exhaustion and fear during the rescue are palpable, as is her understanding of the ocean as potentially dangerous, where ghost-like waves could pull her to her death. In the oral histories carried out, the adults explain their ultimate safe passage and rescue as a miraculous intervention by God.

The scientific analysis of this specific journey involved numerical model predictions of the marine environment during this journey, which is known as hindcasting. These were used in a hydrodynamic model to enable the motion of the boat during the journey to be estimated and, in turn, to understand the various environmental risks the 101 Boat and its passengers faced. By focusing on these scientific methods, we analyse the role of the ocean and its various elements to determine how paradoxically the environment both imperilled and yet saved the boat and its inhabitants. This perspective, we argue, can only be fully understood by working at the interdisciplinary juncture between historical research and scientific data and analysis. In this way, ocean engineering creates a scientific narrative that enables us to move towards theorizing the ocean as an active agent, and place these findings in a productive conversation with historical methodologies and analysis.

While this case-study focuses on one journey, it invites reflection on how the fields of refugee studies and migration histories, histories of humanitarianism, and environmental histories can be expanded and connected when carried out as part of a scientific reconstruction of past events. In this case, we consider the paradoxical position where the ocean created both the conditions for severe danger as well as facilitating a humanitarian rescue. But how did it do this in environmental terms? Before we address this question, what follows is a survey of ocean historiography and the wider historical context within which the experience of those on board 101 Boat must be understood.

I

Oceans, seas, and bodies of water have been part of journeys across the centuries that people have taken when forcibly displaced.Footnote 3 As a part of these travels, oceans have been sites of both danger and salvation.Footnote 4 We see these terms not as a binary opposition or an ‘either/or’ proposition of a fixed system, but as paradoxical possibilities that exist in a dynamic site that acts and reacts in relation to the environmental, physical, and social realms and that constantly and continuously moves between danger and safety.

Oceans have been central to historical analysis, and a rich and innovative historiography has emerged in oceanic histories in recent times.Footnote 5 Studies have explored historical aspects of environmental protection; sovereignty and law; diplomacy and fishing; and the social and cultural construction of the oceans over time and place.Footnote 6 Methodologically, the subject of oceans has been examined in relation to global histories, maritime history, and imperial history and Western cartography.Footnote 7 Within environmental history, studies of the powerful and significant role of weather conditions and climate changes within social and historical contexts has been charted and analysed.Footnote 8 But within these accounts, refugee boats on the oceans have drawn little attention from historians.

In the field of refugee studies, there has been a more sustained interest in the relationship between oceans and refugees. In writing about the importance of history to refugee studies, and considering how future historians might analyse forced migration in and around the Mediterranean, historian Peter Gatrell proposes the scholarly significance of ‘thinking through oceans’. He suggests that this might enable scholars to consider the multiple scholarly understandings of oceans and historians ‘to look beyond the boundedness of the modern nation state’.Footnote 9 As Gatrell states, ‘In cultural-historical terms, oceans are invested with meanings of adventure and opportunity, as well as constraint and risk.’Footnote 10 Refugee history should include a broad view of ‘politicized messages and expressions of oceanic humanitarianism’.Footnote 11

Oceanic humanitarianism has been the subject of many studies, and these have provided valuable insights into the very nature of rescue on the seas.Footnote 12 Within the vast historiography on the history of humanitarianism throughout the twentieth century, oceanic humanitarianism has not featured as distinctively as a category of analysis. Rather, the historiography has focused on humanitarian interventions through governments, organizations, and individual and international bodies.Footnote 13 Assistance on the oceans has been unproblematized, without due attention given to two aspects: the very nature of the ocean itself and the use of meteorological and oceanic material to enhance this understanding.

Where scholarship has charted the journey of Vietnamese refugees, it has done so by examining the actions of people, groups, and institutions.Footnote 14 In writing of the sea journeys people took to leave Vietnam, Nancy Viviani has described these experiences as ‘legion’ and ones that ‘represent a chapter in the human history of great stoicism, courage and self-sacrifice’. She notes that these boat refugee journeys are ‘entwined with the less noble qualities of rapacity, cruelty and indifference’ enacted by both individuals and states.Footnote 15 Viviani writes exclusively in terms of individuals, the state, and government policies and structures. As a point of departure, in this research we extend the focus of analysis to include the water on which journeys took place. Using scientific and mathematical tools of analysis alongside oral histories, we develop complementary and nuanced understanding of the role that the ocean and weather played in the boat journeys people took when escaping Vietnam.

The extensive scholarship on oceans and refugee journeys in literature outside of history has been especially insightful with regard to exploring the oceans from the perspective of psychological understandings and lived experience; about images and discourses; the notion of the nation, its limits, and reconceptualizing the nation-state; and the sea at the intersection of space, borders, and regions.Footnote 16 We note that environmental conditions have been examined in geographical research about piracy, but not in scholarship on boat refugees, and these do not employ a historical methodology.Footnote 17 The call for critical ocean studies has led to efforts to examine the depths of the ocean in relation to feminist and Indigenous epistemologies; militarization of the sea; linking geopolitics to the poetics of the sea and its fluidity and flows.Footnote 18 In studies of literary representations, the influence of oceans in shaping understandings of Vietnamese subjectivity reveals how displacement on the open seas and water can provide a powerful framework through which to explore the complex intersection between notions of the diaspora, community, home, and nation.Footnote 19 What these bodies of scholarship about oceans share is an absence of a scientific reconstruction. This research adds another dimension to ‘the waterscape of the boat and of the sea’ that Vinh Nguyen terms ‘oceanic spatiality’.Footnote 20

In researching refugee boat journeys, oral histories and historical records provide personal and descriptive understandings of the ocean. The scientific reconstruction and narrative developed in this collaboration do not supersede these sources or tell the ‘truth’ about the ocean, but, by carrying out ocean engineering analysis, we can gain access to how the ocean acted, and the effects of this on specific vessels. In the case of the 101 Boat, we show how this particular rescue was possible, and how those in the 101 Boat were dependent on the acts of ‘nature’ for their survival, as oceanic humanitarian action was dependent on nature, too, to be effective.

II

Escape by boat is central to the history of forced movement of people from Vietnam. The term ‘boat people’ was first used in the late 1970s to collectively refer to those who fled Indochina on small boats after the Vietnam war (1955–75) ended.Footnote 21

The numbers of people who left Vietnam and ways they travelled changed in the aftermath of the war. Between April and mid-May of 1975, approximately 135,000 Vietnamese were evacuated or left.Footnote 22 Over the next three years, around 20,000 people arrived in countries of first asylum.Footnote 23 In March 1978, the Vietnamese government closed all private business throughout the country.Footnote 24 This preceded the largest movement of people out of Vietnam, particularly Vietnamese of Chinese ethnicity who dominated business, as well as those in the South who had been subject to government surveillance and control after the end of the war.Footnote 25 In 1979, the Orderly Departure Program was established. The scheme was for family reunions and ‘other humanitarian cases’, and the Vietnamese government authorized the exit of people and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) co-ordinated their resettlement.Footnote 26 This operated for fifteen years and saw more than 650,000 people leaving Vietnam and being resettled elsewhere.Footnote 27

The total number of people who left Vietnam, either by sea or land, after the end of war in 1975 is not known. Only those who arrived in countries of first asylum were formally counted.Footnote 28 The overwhelming majority of these people, 95 per cent, left by sea, and totalled almost 800,000 people in the twenty years after the end of the war.Footnote 29 Countries of first asylum were ones geographically close to Vietnam. By land, people fled to China and Thailand, and by sea to Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Philippines, Hong Kong, and Macau, and, further away, the Republic of Korea and Japan.Footnote 30 These were not, however, the countries where people were ultimately resettled. In international negotiations, Hong Kong and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries insisted that people arriving by boat would not be settled in their own countries, but be settled elsewhere, with the UNHRC co-ordinating the movement of people.Footnote 31 By the end of 1977, boats with Vietnamese refugees were regularly pushed back out to sea when attempting to dock in Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand.Footnote 32 These pushbacks, combined with merchant ships refusing to assist Vietnamese refugees in boats, resulted in people perishing at sea and created what Judith Kumin described as a vivid and dramatic ‘denial of asylum’.Footnote 33 Overall, an estimated 10 to 15 per cent of people who began the journey died at sea, and UNHCR reports that between 200,000 to 400,000 people perished.Footnote 34

Piracy was a considerable risk to refugees who escaped by sea. After the Vietnam war ended in 1975, piracy increased because of political instability, availability of weapons, and the very presence of boat refugees.Footnote 35 UNHCR statistics recorded that of the 452 refugee boats with 15,479 people who arrived in Thailand in 1981, 77 per cent (349 boats) had, on average, been attacked three times. In numerical terms, this included the rape of 578 women, abduction of 228 women, and 881 people being reported as either dead or missing.Footnote 36

Refugees who escaped by sea soon after the end of the war generally travelled on small fishing boats which were often overcrowded but with less than one hundred people on board. From late 1978, larger vessels, which were also overcrowded, were on the sea and they attracted considerable media attention and featured in international debates.Footnote 37 While most of the fishing boats were ill equipped for sea travel, there was a possibility of being rescued at sea, and this increased the willingness of Vietnamese refugees to undertake the journey. Non-government organizations such as MdM and commercial boats owned by civilians rescued Vietnamese fishing boats in distress and assisted them to reach refugee camps in South-East Asian countries of first asylum.Footnote 38 The ocean journey was a risky one, but there was also the possibility of humanitarian assistance.

The Vietnamese refugee exodus by boat from 1975 until the early 1990s contributed significantly to the rise of oceanic humanitarianism. From 1975 to late 1978, commercial ship captains from thirty-one different countries rescued 186 boats carrying refugees.Footnote 39 There was, however, international pressure from South-East Asian countries to discourage this method of seeking asylum. Governments of surrounding South-East Asian countries declared they were overwhelmed by the sea arrivals of refugees. In just seven months during 1979, 177,000 Vietnamese boat refugees from forty-seven boats had arrived or were rescued at sea in the South-East Asian region. There were more boat refugees at this time than the 110,000 rescued at sea in the initial three years. Half the rescues, moreover, were by ships from only three of the thirty-one countries that had rescued refugee boats in those initial three years.Footnote 40 The number of boat refugees and pushback of boats from ASEAN countries prompted the UNHCR to convene and discuss international co-operation for the provision of refugees at sea.

In 1979, eight Western countries guaranteed resettlement for any Vietnamese refugees rescued at sea even if the merchant ship was from a state that did not resettle refugees.Footnote 41 These provisions were not enough to manage the swelling numbers of refugees, which did not abate until the 1980s. Special considerations for protecting people seeking asylum at sea were proposed in 1980 by the UNHCR and included a call to give full effect to the 1958 Geneva Convention on the High Seas to supress piracy.Footnote 42 The Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) convened in December of 1982 to recognize the ocean as an international space that required comprehensive law and order to govern its uses.Footnote 43 The duty to render assistance in UNCLOS (Article 98) was required for people in distress or in danger of being lost at sea, but there was no explicit provision for people seeking asylum.Footnote 44 Oceanic humanitarianism developed around this provision, and the UNHCR campaigned to share the work of rescue and proving asylum at sea. By 1982, there was renewed international humanitarian co-operation for boat refugees. For the 101 Boat refugees, the French navy was on its second mission working with MdM on Le Goëlo when they were rescued.Footnote 45 It was such sea missions to save Vietnamese boat people that saw the emergence of MdM in May 1980.

Medical doctor Bernard Kouchner founded Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in France in 1971. MSF refused to take part in Kouchner's plan for doctors to use a boat to rescue Vietnamese refugees escaping by sea, so he broke away and established MdM.Footnote 46 Those in MSF who opposed ocean rescues saw this as beyond their medical humanitarianism, which they deemed as more effective in refugee camps in Thailand.Footnote 47 Other points of conflict were around Kouchner's use of the media to support work and the political agenda of the organization.Footnote 48 MdM's rescue of the 101 Boat on Le Goëlo was filmed and publicly profiled to aid emerging oceanic humanitarianism.Footnote 49 The French were not alone in providing humanitarian assistance on the seas; German emergency doctors also worked to save lives by rescuing Vietnamese ‘boat people’.Footnote 50 Boat rescues and patrols were expensive to finance and by August of 1982, MdM lacked funds to continue and other rescue ships from Norway, West Germany, and the US had also stopped working in the region.Footnote 51

Oceanic humanitarian efforts increased in June of 1985 when fifteen countries offered resettlement for refugees rescued at sea and reimbursed ship owners for costs to alleviate financial disincentives to providing rescue.Footnote 52 However, when the 101 Boat set sail from the shores of Vũng Tàu in 1982, these provisions were not in place. The organizers had heard of humanitarian assistance from other resettled refugees who had been rescued, but the risks of the ocean journey remained unknown and could not be underestimated. In order to understand these risks, an ocean engineering research methodology has been employed, which creates a scientific narrative to further elucidate the actions of the ocean as a humanitarian agent.

III

In order to understand the localized weather and ocean conditions during the 101 Boat journey and how the vessel responded to these conditions, a model which predicts the marine environment during past events – known as hindcasting – was used alongside estimates of the motion of a vessel in specific sea conditions to more fully understand the interactions between the vessel and the environment.Footnote 53 This ocean engineering analysis provides a detailed understanding of the role of the ocean in terms of risks and dangers faced by those on board the 101 Boat and the reconstructed motion and hypothetical route of the vessel. This scientific analysis revealed that the weather during the journey was extreme and dangerous for a vessel of the size of the 101 Boat, but, at the same time, the environmental conditions kept the vessel away from the most severe region of the storm, and (almost) pushed it to a position where it could be rescued by Le Goëlo, MdM's vessel on an oceanic humanitarian mission.

Historical model data for marine conditions in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand over the past forty years were retrieved from the ERA5 database, which contains global hourly estimates of atmospheric, land, and oceanic climate conditions from 1979 to the present.Footnote 54 Data used for this analysis included wind speed and direction, average wave height (the significant wave height (Hs) a representation of the average of the highest 33 per cent of waves in a given sea state), wavelengths, and wave periods. Oceanic conditions have been used to derive the environmental conditions the 101 Boat journey encountered, and, from that, infer climatological properties of the area and evaluate the severeness of the storm.

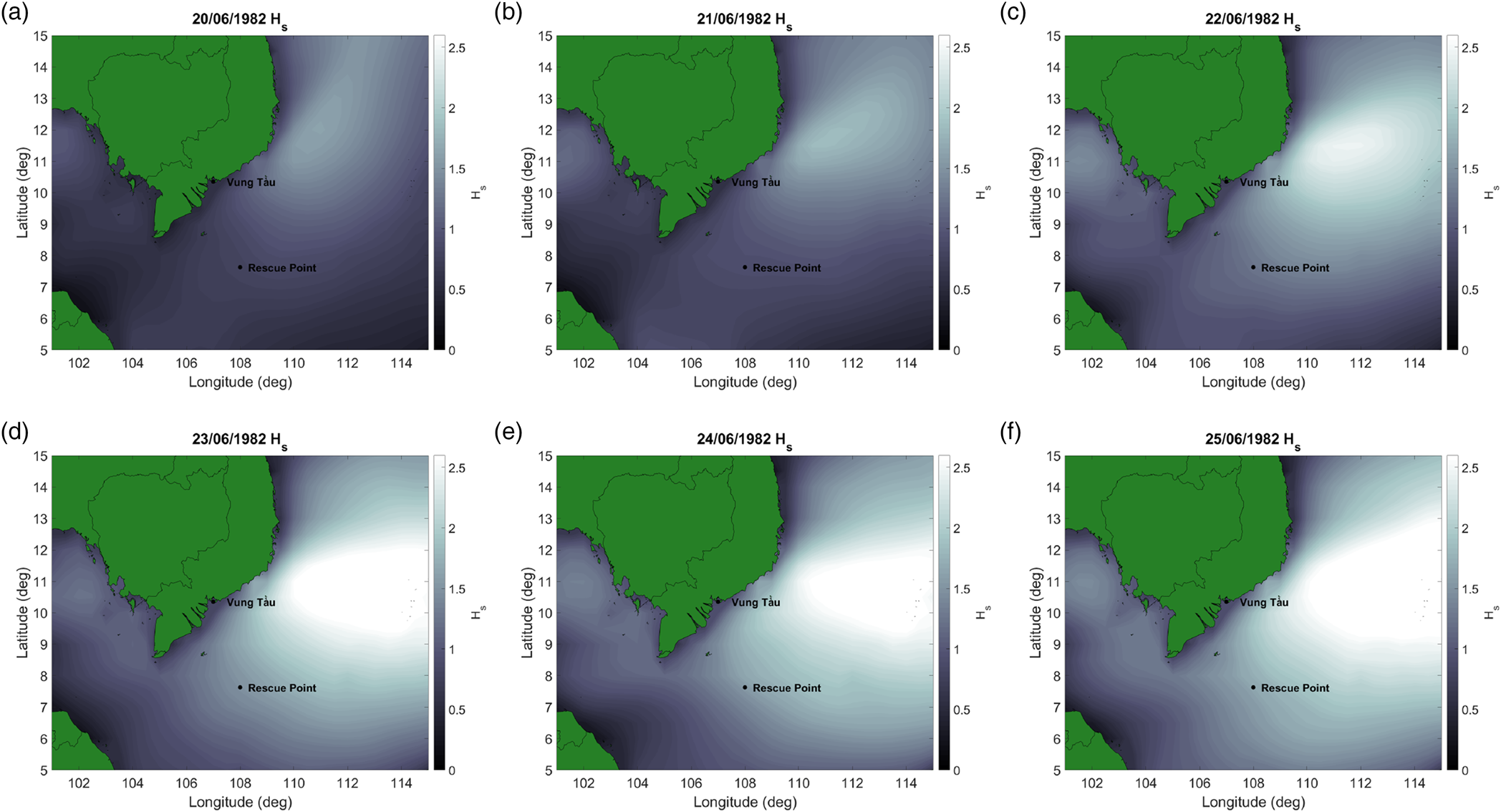

The 101 Boat was approximately 2.5 m wide and 10 m long, and was overloaded with more than double the passengers it was designed to carry.Footnote 55 When the boat departed Vũng Tàu on the morning of 20 June 1982, two storms were active: one mild storm developed in the Gulf of Thailand and one, far more severe, was in the South China sea between Vietnam and the Philippines. The vessel was caught in heavy seas soon after the journey began, which prevented it reaching its intended destination in the Philippines. Those on board recalled mild sea conditions on 21 June and severe storms the next day which caused the boat's engine to stop operating for at least half of the day. On the following day, 23 June, all on the boat were rescued at sea. The storm that the 101 Boat encountered was extreme, with wave heights at the centre of the storm being consistent extreme values expected once in a hundred years. The weather conditions, mapped in Figure 1, show that the significant wave height increased over four days and that the storm in the South China sea reached its full power on the day of rescue.

Figure 1. Significant wave height (Hs). Showing the development of the storm in the South China Sea between 20 and 25 June 1982 in relation to the point of departure and rescue of the 101 Boat. The significant wave height (Hs) is in metres and is a representation of the average of the highest third of waves in a given sea state.

Based on the modelled sea state, the motion of the 101 Boat was reconstructed across three different planes of movement: heave, roll, and pitch. The heave is the movement of the vessel up and down in the water, pitch is the see-saw type movement of the vessel from front to back, and roll is the tilting movement side to side.Footnote 56 Motion over these three planes is significant for a vessel's stability in the water.Footnote 57

The location where the boat was rescued was at the edge of the storm footprint where waves were smaller, about 60 per cent of the maximum values recorded elsewhere during the storm. In absolute terms, the waves were approximately 60 m long (six times the length of the vessel) with an average height of 3 m. This means that some individual waves reached the height of about 6 m. Under these circumstances, the boat would have sailed against the waves, as far as possible, and at very slow forward speed to limit motion and maintain stability. Even so, the pitch and especially heave motion was excessive. Consequently, extreme motion and large waves had the capacity to force water to smash on the ship's deck, which would have flooded the lower deck and engine room when the boat was at the wave's trough. This was also recorded in the oral histories of those on board, and for them, a 6 m wave would have appeared as a wall of water falling on the vessel.

The collective environmental force was far greater than the machine power of the boat and determined the final part of the route the 101 Boat took. Even when operating, the boat's engine was already underpowered for the load it was carrying, and the engine stopped working for at least half a day during the journey after the engine room flooded. Without engine power the vessel exposed its side to waves and began to drift. Wind and wave conditions both pushed the vessel in a southerly direction. In scientific terms, this environmentally forced drift exerted on the 101 Boat (a free-floating body) were estimated and shown in Figure 2.Footnote 58 This caused the boat to move around the edge of the storm, rather than directly to the areas of greater danger directly east (see Figure 3), where those in charge of the boat had initially intended to go.

Figure 2. Predicted drift directions and intensity (depicted by the length of the arrow) for the 101 Boat on 22 June 1982 based on wind and wave forces acting on the vessel.

Figure 3. Visualization of the severity of the storm expressed as the ratio of the significant wave height recorded during the event to the maximum wave height.

The risk of an accident for the 101 Boat was considered in the analysis of the vessel's motion, and heave presented serious problems when it was 3 m or more.Footnote 59 Using this, an average risk was calculated over five days from 20 to 25 June 1982. Figure 4 shows that the 101 Boat was rescued in an area of moderate danger and that the area of significant danger was east towards the Philippines on the planned route.

Figure 4. Generalized regional model of risk. Risk calculated for the 101 Boat in the region combining key motion of heave, pitch, and roll. Risk is defined as the ration of predicted heave to 30% of the boat's length (low risk, heave <15% of boat length; medium risk: 15% of boat length ≤ heave <30% of boat length; high risk, heave ≥30% of boat length).

Hindcasting provides an understanding of how the weather and ocean both helped and hindered the journey of the 101 Boat. With this engineering approach, a scientific explanatory narrative has created a unique dimension to understandings of the experience of refugees on the ocean. Coupled with historical context and analysis, a nuanced understanding of the ocean as both destructive and liberating for this group of refugees is captured. The historical memories of some of the refugees who were aboard the 101 Boat create a different explanatory narrative, one that again focuses on both hazards and guardianship provided by the ocean, but the key orientation of that narrative is religious. The safe passage of the refugees is understood by them to come from God as the ocean is understood to be within God's command. These historical memories and narratives are explored through a series of oral interviews undertaken with survivors as their story telling reflects the paradoxical nature of the rescue of 101 Boat.

IV

Oral histories, alongside public acts of remembrance by those on 101 Boat, provide an opportunity to explore how the survivors remember and frame their understandings of the ocean in their journey of escape. The explanatory narrative is of the ocean as a force of God that delivered them to their rescuers. As Ann Tran, a survivor of the journey of 101 Boat described it: ‘God created the storms so as to put 101 of us into the cradle of the Le Goëlo ship.’Footnote 60 The ocean is characterized as God's will, which embodies the paradox of danger and saviour played out in their narrative of the boat journey. This was most striking in a 2019 Catholic mass and public memorial ceremony for the survivors of the 101 Boat and other Vietnamese boat refugees who resettled in Paris. The memorial ceremony, held after the mass, included testimonies from some of the 101 Boat refugees and refugees from other boats and Catholic songs about God as their saviour. The mass and memorial served as an annual ritual of giving thanks to God for their survival and remembering those who had drowned on other refugee boats. Their political opposition to the North Vietnamese government is pronounced and a number of survivors testified that their faith in God was solidified after their boat journeys and resettlement. Pictures and films posted on Vietnamese Refugee Facebook community pages also give thanks and memorialize boat journeys as safe passages for Vietnamese Catholics. Facebook provides an ongoing and dynamic form of commemorative practice of this and other boat journeys by the diasporic Vietnamese community.Footnote 61

The oral histories examined below were collected the day before the 2019 annual mass and memorial ceremony in Paris, France. They were conducted with the organizing group of 101 Boat who planned the escape. These included Ann Tran and Chuong Nguyen (Nguyen Austen's parents) who financed the initial costs of building the boat. Hoa Nguyen, a cousin-in-law to Ann, was the primary co-ordinator of the operation. Hoa was responsible for having the boat built in secret, selling passages and arranging for guides to get the boat to sea. Khanh Nguyen, a former naval officer for the South Vietnamese army, was the navigator. Thanh Nguyen, an experienced car mechanic, was responsible for building and maintaining the engine. Chuong and Hoa only sold passage to or hired people they knew well and trusted to keep the operation secretive as those planning to escape risked arrest and punishment. These main actors referred to as ‘the inner circle’ included their children and extended relatives who accounted for fifteen people.

The families of the inner circle and those who had paid for their passage from the inner circle were devout Catholics. They were from families who had resettled in Bien Hoa in South Vietnam in the 1950s who had escaped religious and political persecution as dissidents in the North at the end of the French Indochina war. While North Vietnam was controlled by the Vietnamese Communist Party led by Ho Chi Minh, the South was not yet fully under communist control and still offered opportunities for individual commerce which was the work Ann and Chuong's families were involved in. The inner circle only spoke about and sold passages to those they knew and trusted from the church. As a result, the majority of the 101 Boat passengers were anti-communist Catholics who had the means to afford their passage.

The 101 Boat journey began with numerous unplanned events that contributed to the rescue at sea, including the overloading of the boat they were to escape in. The families of the inner circle arranged to be housed and hidden with families in the port city of Vũng Tàu before getting to the boat. They packed up their houses on the pretext of visiting relatives by the seaside. The first meeting point was to get to the boat by midnight. Families marched in the dark through the marsh and river estuaries. Nguyen Austen remembered it was dark and scary with fear of armed members of the communist organization, the Viet Cong, who were on patrol for escapees. When the families arrived at the boat, the scene was complete chaos. Unbeknownst to the inner circle, the hired fisherman had sold passages to others. There were also other desperate escapees hiding in the marshes waiting to jump on board without having paid for passage. The fisherman held Hoa's wife hostage until the people he had sold passage to boarded and other local escapees jumped on board.

At the time of departure, the inner circle were unaware of how many people were on board the vessel that was built to carry between thirty and forty passengers. Amidst the bedlam of boarding, one of the male passengers suggested to Hoa that they use a stick to beat back the people from jumping on board and throw off the passengers who had not paid for their passage. Hoa, however, decided that their fates were sealed and determined by God. He broadcasted to the potentially mutinous paid passengers that it was God's plan if they were to make it out alive or die; everyone on board was entitled to share that fate of freedom or death.Footnote 62 According to Pierre Blanchet, the French newspaper reporter who witnessed the MdM rescue, the boat was a walnut shell and he was surprised by the number of people on board: ‘The refugees numbered a hundred and one. You read correctly: a hundred and one on a boat nine and half metres long.’Footnote 63

In addition to the boat being overloaded with unplanned passengers, it headed in the wrong direction upon leaving the shores of Vietnam. Prior to this escape, Hoa had been on practice runs where they pretended to be a fishing boat with one or two fishermen at the top and others below deck. When they launched at dawn, Hoa immediately noticed that they were off course and headed through control gates where Vietnamese officials would have stopped fishing boats to check them for illegally carrying refugees. Fortunately, the patrol boats had already left to check the other parts of the shoreline and missed the 101 Boat. As Ann recalled,

When we headed to the open sea, we had already mistakenly gone into the gate of the border control police. The person who was hired as our guide had already jumped off the boat, because he knew that the police was out there to intercept escaping boats on that day. Hoa exclaimed at that time: ‘Oh my God, we have already gone the wrong way!’Footnote 64

Ann considered this navigational mistake to be an act of God to protect them from the danger of imprisonment: ‘God created that mistake so that our boat was the only one that could escape…on that day.’ Someone incorrectly brought news to Ann's parents ‘that we had already been arrested, because no boat could successfully escape that night’.Footnote 65 The Vietnamese boat patrol was presumably preoccupied with the other boats captured that morning. Fortunate as they were, the 101 Boat faced more challenges prior to their rescue.

Once at sea, the 101 Boat faced the danger of capsizing due to the waves and storms that were ahead of them. Pierre Blanchet reported, ‘Scarcely several hours after the rescue of the hundred and one refugees, a very strong monsoon wind rose up over the South China Sea; the people would not have survived if they had stayed in their skiff.’Footnote 66 As the hindcasting above has confirmed, the storm was of a once in a hundred year magnitude. The 101 Boat proved seaworthy for four days before rescue. The first day at sea was reportedly calm, and the intention was for the boat to head east to the Philippines. Khanh, the navigator, recalled,

I knew how to head for the Philippines, for sure. If unsuccessful, we may turn to Malaysia, which was better for us. We did not want to go to Thailand, because there were pirates. But the boat did not go on the right direction to the Philippines; and it drifted to Thailand.Footnote 67

In retrospect, Khanh was aware of this paradoxical possibility of danger and rescue at sea. He acknowledged that the wind and weather conditions on the ocean caused them to head towards Thailand where there was a danger of pirates. As Chuong described in his conversation with the MdM boat captain upon rescue, the dangers at sea included theft, death, and burning of boats by Thai pirates. When Chuong was asked, ‘Where did you plan to go?’, Chuong replied to the captain: ‘“We had planned to head for the Philippines.” He (the captain) told me: “You made a mistake. Do you know who was waiting for you on your back?” And he continued: “Thailand. The Thai pirates were waiting for you! There was no way you could get away from them.”’Footnote 68

Attacks by pirates, particularly in the Gulf of Thailand, were a danger to boat refugees at this time. The inner circle, aware of this, had planned to travel to the Philippines. The storm, however, had put them off course towards their rescuers and heading in the direction of Thailand. Aside from putting them in harm's way of a pirate attack, the storms also threatened their physical and mental well-being. As Ann recalled, ‘On the second day, out in the open sea, the people on the boat were thirsty.’ Expensive cans of freshwater had been purchased for the journey, but it was undrinkable ‘brackish water’ from a river or a creek. The lack of adequate drinkable water while adrift in the open sea was, paradoxically, resolved by the storms.Footnote 69 Bac Hoa Gai, Hoa's wife, characterized the storm as a Godsend that brought them to the point of rescue: ‘It was because of the storm that we headed for that direction; and it was also because of the storm that we had water to drink.’Footnote 70 Ann spoke at the 2019 memorial on behalf of the inner circle and 101 Boat survivors in attributing the storms as an act of God that saved them from dying. ‘But when we began to feel thirsty, it started raining, and the storm was coming. And we did not have to use a single drop of water in those cans that we had bought before. God gave us drops of pure and fresh water, from heaven.’Footnote 71 However, these storms that brought reprieve to their thirst also endangered them. Ann acknowledged the impact mentally,

We were struggling with the storms for two days. As a matter of fact, at that time, I only saw a grey black colour when I looked down at the sea. And when I looked at my children sitting inside the boat, I asked myself: ‘Is this journey a big mistake of mine?’Footnote 72

Despite genuine doubts about their escape, Ann and other passengers on the boat have memorialized the journey as one which saw them being miraculously saved from peril by divine intervention.

While the storms provided the refugees reprieve from thirst, they further put them at risk of capsizing. As Thanh, the mechanic, recalled, ‘The boat was overloaded like that, the engine was overworked, and it would break down easily, suddenly…The engine often went dead, when the winds and waves were strong.’ He said that whenever a wave hit the boat, the engine would lose power to propel forward. The 101 Boat drifted at sea without a working engine. He would use the hand crank to restart it, but at times the diesel pipe was flooded. They would have to wait for it to dry. Thanh explained, ‘Sometimes a few hours, sometimes it took only half an hour. It depended on how strong you could crank the engine.’Footnote 73

After the engine failed during the storms on the second and third day, the 101 Boat drifted southwards, into commercial shipping areas, where the Le Goëlo rescue ship found them at ‘latitude 7°38′ North, longitude 108° East…in the South China Sea at the southern limit of the Gulf of Thailand’.Footnote 74 As Bac Hoa Gai emphasized, while there was doubt that they would survive the sea's force, they placed their hope in the belief of God's command over the journey: ‘Rain and sunshine are also the will of heaven, and heaven created the storms. So heaven is under the command of God who helped us to successfully escape.’Footnote 75

V

Oral history and the numerical model predications highlight the paradoxical role of the ocean and weather as a force of danger and survival for the refugee passengers of the 101 Boat. The hindcasting illuminates the ocean conditions during boat refugee journeys and the oral histories provide individual and group reflection on the meaning of the impact of those conditions that lead to their rescue. The interaction of ocean engineering analysis and oral history interpretations provides an interdisciplinary understanding of this boat journey, and its place in the history of oceanic humanitarianism. The boat engine was not powerful enough to travel to the Philippines through the storm, but the ocean conditions took the 101 Boat to international waters, where the commercial ships might possibly rescue them. The oral history and scientific narratives not only complement each other, but, together, they add depth to historical understandings and memories of the event. Thanh, the engine's caretaker, recalled that the storm caused the boat engine to cut off three times during their journey.Footnote 76 He explained his understanding of the magnitude of various storms at that time.

When it was about to rain, we called it ‘squall’. It was like a storm. It could be seen as a ‘level five’ [storm with] level four or five wind. The boat often travelled slowly when it was heavy. It could not go fast when there was winds and waves. On many occasions when the winds were strong, the boat's bow kept raising up and then slamming down, and this caused the engine to be less powerful and lose balance.Footnote 77

In line with the reconstructed conditions at sea, the oral testimonies describe the perceived average and extreme conditions that those on board remembered. Thanh's conclusion then was that the storms and waves of water that came on board stopped the engine, ‘For example, in the last time, the diesel pipe was blocked, and diesel could not flow down freely.’Footnote 78 Thanh described this final challenge with the storm conditions and engine as a half a day without engine power, ‘because the lid of the diesel can was soaked in sea water when the waves hit’. When the lid dried, the salt remained and ‘It kept going like that and it created layers of salt that prevented the air from entering the diesel can.’ Thanh attributed his understanding of the situation to prayer, ‘At that time, it was because of the grace of Jesus and Mother Mary that I could figure it out. I understood that it must be the lid that prevented diesel from flowing down the engine.’ He asked others to help him to start the engine, ‘but no one could do it because they were all exhausted’.Footnote 79 Thanh ended up cranking the engine himself, but it stopped working again, and they drifted: ‘We then kept going until we were picked up by a ship. It was the last time. The longest time when the engine went dead.’Footnote 80 Understanding the sea state and boat's motion in scientific terms alongside oral history narratives about the engine failure provides a more detailed historical picture of events, and reveals the ways the ocean impacted on the journey.

Risk as modelled through hindcasting is a form of narrative that stands alongside the survivors’ understanding and representations of the miraculous events that led to their rescue. If it had not been for the overloaded and underpowered boat in these particular weather and ocean conditions, the boat might not have been part of the first Le Goëlo rescue mission for MdM. Furthermore, oral histories and hindcasting attempt to manifest the uncertainties that govern the fate of boat refugees. Insights from each discipline explain the uncertainty and elements of luck that allowed 101 people to survive on a 10 m ‘walnut shell’ at sea for four days. The main risk, aside from these events beyond their control, was that the boat would break under the storm conditions and waves of the ocean and those on 101 Boat would drown. The specific scenarios of how individuals struggled against such conditions at sea is revealed through the oral histories.

Scientific analysis in the form of numerical and hydrodynamic modelling have limitations. These approaches cannot anticipate the cultural dimensions of the experience of refugees on the oceans, such as the role and meaning of the ocean and its characterization as God in the oral history narratives about the boat journey. Neither can they reveal the importance of memory, commemoration, and community that has been built around this experience and their identities as boat refugees and beneficiaries of oceanic humanitarianism. Furthermore, oral history and hindcasting narratives about boat refugees bear the watermark about the probable boat journeys of the estimated 200,000 to 400,000 who attempted escape and drowned.Footnote 81 Significantly, these integrated narratives highlight more broadly how an interdisciplinary approach to understanding the ocean is central in the interwoven histories of MdM, non-government agencies, governments, and military collaborations in oceanic humanitarianism and forced migration.

VI

Focusing on the scientific elements of the ocean allows us to explore the way the ocean occupies a paradoxical place in the history of refugee boat rescues. The ocean creates dangerous and perilous conditions which are life threatening. In the instance of 101 Boat, we can see the environmental conditions created a once in a century storm that imperilled the lives of all those on board. The ocean conditions were very dangerous for the 101 Boat; the extreme waves crashed on to the vessel and caused the engine to stop working. The boat's motion was then entirely determined by wave conditions and was at risk of breaking up or capsizing. The mapping of environmental conditions revealed how the wind and wave conditions likely kept the boat on the edges of the storm, nowhere near where those who planned the journey intended to go, but which became the location in which they were rescued.

Simultaneously and paradoxically, the ocean created the dangerous circumstances which provided the conditions for humanitarian rescue. In the oral memories of the occupants of the 101 Boat, this is interpreted as divine intervention, as a miracle. The change in course of the ship was dramatic and unanticipated and those on board held strong beliefs in God and Catholicism. By framing this history of a refugee boat journey through a scientific paradigm, the way in which the ocean is rendered as treacherous and potentially murderous but also as a path to rescue is revealed as a complex and multi-layered historical event. It is only by drawing together the methodologies of historical analysis, oral histories, and hindcasting that a full appreciation of the experience of such refugee boat journeys can be captured, and the actions of the ocean come sharply into focus. These methodologies provide, more broadly, new directions for studies of refugees by boat, which are enhanced beyond one historical method. Transformative knowledges are generated through these intersecting methodologies and provide a paradigm that creates a distinctive body of evidence and a new compelling oceanic archive for future research. This approach not only enriches Vietnamese boat people narratives, but applied to other histories of refugee migrations across time and place, can enable the ocean to be understood as an active multi-dimensional agent, encompassing its scientific as well as its historical and mnemonic dimensions. In rewriting the histories of oceans and displacement in this way, the ocean can be shown to define and shape historical events with new perspectives.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editors and anonymous referees for their generous advice and helpful comments. We are also very grateful to Susan Broomhall for her insightful and constructive comments on earlier versions of this article.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.