Introduction

Binge eating consists of ingesting large quantities of food in a short period of time. Binge eating disorder (BED) is a mental disorder characterized by the occurrence of regular episodes of binge eating (ie, at least 1 day a week for 3 months). In contrast with bulimia, no purging behaviors, such as forced vomiting or taking laxatives, are observed in BED. The lifetime prevalence estimates of BED, based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–fourth edition (DSM-IV) criteria, are 3.5% among women and 2% among men.Reference Hudson, Hiripi, Pope and Kessler 1 Lisdexamphetamine is the only pharmacological agent approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) but has the potential for abuse, dependence and serious cardiovascular-related reactions.Reference Heo and Duggan 2 Tricyclic antidepressants, cognitive behavior therapy, interpersonal therapy, and behavioral dietary treatment have all been found to be effective in controlled studies in decreasing the number of binge eating episodes in BED with or without weight loss.Reference Reas and Grilo 3 Topiramate also constitutes another pharmacological option for treating BED. Topiramate is an approved medication for epilepsy. Its pharmacological mechanisms involve potentiation of gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor subtype A, inhibition of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors and kainite receptors, inhibition of L-type calcium channels and voltage-dependent sodium channels, activation of potassium conductance, and weak inhibition of carbonic anhydrase (CA) isoenzymes.Reference Johnson and Ait-Daoud 4 Topiramate has been found to decrease the frequency of binge eating episodes in several clinical studies assessing weight loss, 5-8 though its tolerability profile can also limit its use.Reference McElroy, Shapira and Arnold 9 For example, topiramate has a dose-related effect of cognitive impairment that could limit its use in clinical practice.Reference Loring, Williamson, Meador, Wiegand and Hulihan 10 A previous systematic review was published on the effect of topiramate in BED, but this review was purely qualitative regarding topiramate efficacy.Reference Brownley, Berkman and Peat 11 Moreover, a previous meta-analysis assessing the efficacy of two pooled antiepileptic drugs (ie, zonisamide and topiramate) on continuous binge abstinence was published in 2008.Reference Reas and Grilo 3 However, no previous meta-analysis has explored the efficacy of topiramate on binge frequency parameters, that is, number of binge episodes per day and number of binge days per week. Such parameters, which include a notion of harm reduction, are important in clinical practice and are more continuous and detailed than abstinence-related parameters.

We thus aimed to fill this gap, with the objective of providing a quantitative review of topiramate efficacy and safety in those with BED to inform clinicians and public health specialists about the current level of evidence of using topiramate in BED.

Methods

We employed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for reporting this review.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman 12 The completed PRISMA checklist can be found in Supplementary Table S1. We prospectively registered our protocol on PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/) under the ID number CRD42019124500.

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

The following electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and ClinicalTrials.gov. English-language articles were searched using the following query: (“Qsymia” OR “Topiramate”[MeSH] OR “topiramate” OR “topamax” OR “phentermine” OR “epitomax” OR “qsymia”) AND (“Binge-Eating Disorder”[MeSH] OR “binge eating disorder” OR “binge eating” OR “eating disorder” OR “BED” OR “loss-of-control eating” OR “loss of control eating”). The last search was performed on November 17, 2019, with no date limits. The reference list of all identified records was reviewed to identify additional studies of relevance. All citations identified by search were independently screened based on the title and abstract by two reviewers (M.N. and L.J.). Each potentially relevant study was reviewed in full text and assessed for all inclusion criteria. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus or with referral to a third person (B.R.).

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) double-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted; (2) adults (ie, ≥ 18 years old) with a diagnosis of BED based on the DSM-IV-TR or DSM-5 criteria, with or without a concurrent psychiatric or addictive disorder, were enrolled; (3) treatment group was based on topiramate; (4) control group was based on placebo and; (5) a psychosocial intervention was allowed if used in both topiramate and control groups.

Outcomes measures

Main outcomes were, as follows: (1) change in binge frequency (ie, number of binge episodes per week) from baseline to last follow-up visit or the differences between groups at the end of the study, depending on the available data; (2) change in quality of life from baseline to last follow-up visit on different scales assessing well-being and/or quality of life; and (3) change in weight or BMI from baseline to follow-up visit (depending on available data).

Additional outcomes were, as follows: (1) change in obsessive–compulsive symptoms and impulsivity outcomes from baseline to last follow-up visit or the differences between groups at the end of the study, depending on the available data; (2) changes in depression from baseline to last follow-up visit on different depression scales; (3) treatment retention measured through dropout rates; and (4) safety features measured using the number of participants reporting serious adverse events or adverse events reported as the cause of a drop out.

Data extraction

Relevant data from eligible articles were then independently extracted to an excel sheet by two authors (M.N. and L.J.). Study authors were contacted in case of missing data. Information on methodology, participants (sociodemographic and clinical information relevant to the review aims), interventions (medications and nonpharmacological interventions), and outcomes measured in this meta-analysis (see outcomes measures section) were extracted.

Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers (M.N. and L.J.) independently assessed the risk of bias in the included studies by using the Cochrane risk of bias tool: ROB-2 (https://training.cochrane.org/resource/rob-20- webinar). Disagreements between the reviewers regarding the risk of bias of particular studies were resolved by discussion, with the involvement of a third reviewer when necessary (M.C.).

Strategy for data synthesis

A review was performed, which aimed to note the following features: (1) type of intervention; (2) target population characteristics; and (3) type of outcome. For each study, the compared effect size between the treatment group and the placebo group is provided by calculating risk ratios for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences for continuous outcomes. When all studies assessed the same outcome but measured it using different scales, the standardized mean difference was used. Heterogeneity was analyzed using I 2. I 2 was interpreted as follow: of low, moderate, and high to I 2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75%. If I 2 was higher than 50% or if I 2 confidence intervals included 50% we performed a random meta-analysis. If necessary we imputed the most conservative standard deviation (SD) values from the p values of the comparative test according to the Cochrane recommendation (http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/).

Modification of the preregistered protocol

We have included a descriptive section on the safety outcomes of each study as a specific profile of tolerability issues with topiramate was found in the review process. We have included the number of binge days per week as an outcome of interest. Although the number of binge days per week is partially correlated with the number of binge episodes per week, we have deemed that both parameters might have an interest for clinicians and patients.

Though initially planned, none of the subgroup or sensitivity analyses were finally performed, because of the small number of available studies.Reference Higgins and Thompson 13 Similarly, as previously recommended,Reference Lau, Ioannidis, Terrin, Schmid and Olkin 14 publication bias was not assessed because less than 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Results

A flowchart detailing the study selection process is provided in Supplementary Figure S1. After eliminating duplicates, the searches provided a total of 275 citations. Of these, 13 studies were assessed for eligibility. In the end, three double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 528 patients met the eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis.Reference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 , Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 , Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15

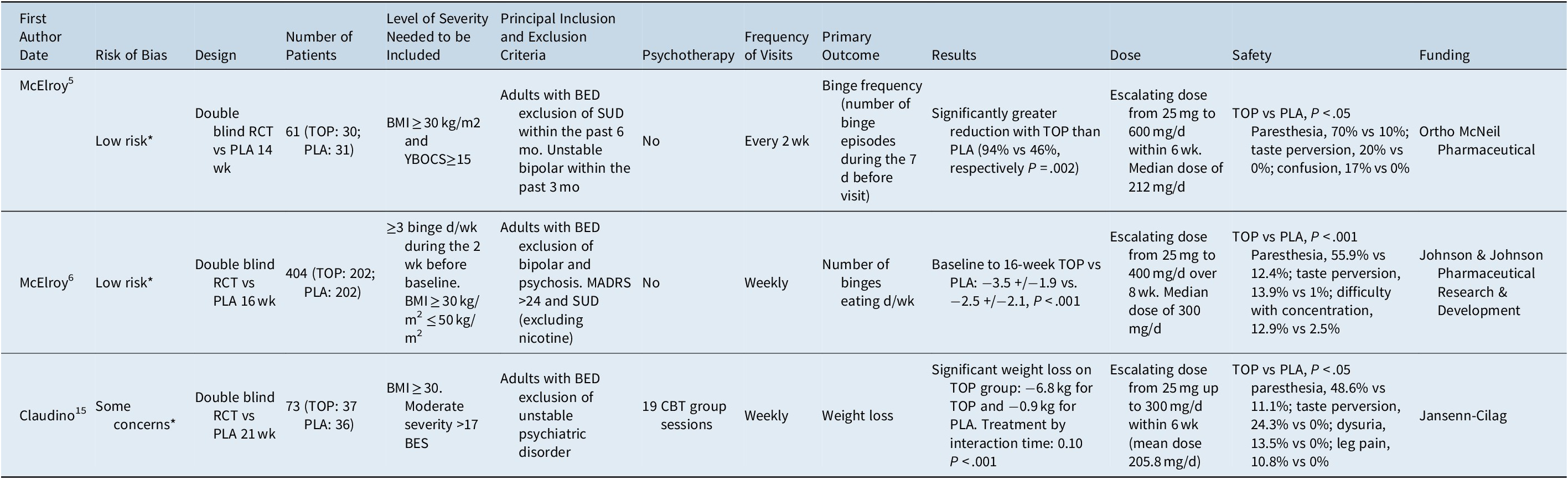

All participants included in the studies met the DSM-IV-TR criteria for BED, and the DSM-5 was not used in the included studies. The mean age was 40 years (range across studies: 41.1-44) for placebo participants and 42 years (range across studies: 35.4-45). One study had 95% of women as participants.Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15 The main characteristics of each study can be found in Table 1 and the extracted outcomes in Table 2. When data were not presented in a suitable form for meta-analysis, for completeness, we summarize the results reported by author in Table 3. The pooled mean weight of the participants at baseline was 108.6 kg (range across studies: 98.4-107) for placebo participants and 108.7 kg (range across studies: 96.6-123.4) for topiramate participants. The mean number of binge episodes per week at inclusion was 5.5 (range across studies: 3.8-6.3) for placebo participants and 5.5 (range across studies: 4.7-6.6) for topiramate participants. The mean number of binge days per week at inclusion was 4.3 (range across studies 3.4-4.8) for placebo participants and 4.3 (range across studies: 4.2-4.6) for topiramate participants. The mean duration of the trials was 17 weeks (range across studies: 14-21 weeks). All three studies assessed the efficacy of topiramate on BED compared to placebo. In one study, participants in both groups received 19 group sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15 Quality assessment of the studies can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

Abbreviations: BED, binge eating disorder; BES, binge eating severity; BMI, body mass index; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg depression rating scale; PLA, placebo; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TOP, topiramate; YBOCS, Yale–Brown Obsessive and Compulsive Scale; SUD, substance use disorder.

* See Supplementary Table S2 for a complete report of the quality evaluation of included studies according to the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias.

Table 2. Results of Outcomes Extracted from the Included Studies

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BIS-11, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Version 11; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MADRS, Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale; NR, Not Reported; YBOC-m, Yale–Brown Obsessive and Compulsive modified for Binge Eating Disorder.

Table 3. Individual Study Reported Results

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BIS-11, The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale version 11; TOP, topiramate; YBOCS, Yale–Brown Obsessive and Compulsive Scale.

The primary outcomes of the included studies were the number of binge episodes per weekReference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 , Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 and weight reduction.Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15 Treatment retention was assessed using dropout rates in all three studies. In all the studies, binge frequency (ie, the number of binge episodes or the number of binge days per week) was assessed during a clinical interview and a review of the patient take-home diaries, in which participants recorded their episodes of bingeing, including the duration of each episode and the amount of food consumed during each episode. Quality of life and impulsivity were assessed in only one study.Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 Obsessive and compulsive symptoms were assessed by the Yale-Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale modified for binge eating (Y-BOCS-BE) was used in two studies.Reference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 , Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 Measures of depression using different scales were employed in the three studies.Reference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 , Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 , Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15 Weight, body mass index (BMI), rate of dropouts and dropouts due to an adverse event were assessed in all three studies.

Studies description

In McElroy et al,Reference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 topiramate was gradually increased over 6 to 10 weeks, with a flexible dose of topiramate (25-600 mg/d). The median dose of topiramate was 212 mg/d, with a range between 50 and 600 mg/d. The topiramate effect on the extracted outcomes can be found in Table 2. Nine patients withdrew from the study because of adverse events (topiramate: N = 6; placebo: N = 3). Paresthesia, taste perversion, and confusion occurred more frequently among topiramate participants compared to placebo-treated subjects (see Table 1). No serious adverse events were observed among topiramate-treated or placebo-treated patients.

In McElroy et al,Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 the same team performed a second and larger double-blind RCT among 401 outpatients. Oral topiramate was gradually increased over 8 weeks to a maximum of 400 mg/d, with a median dose of 300 mg/d. The topiramate effect on the extracted outcomes can be found in Table 2. Twenty-nine (15%) treatment discontinuations in the topiramate group and 16 (8%) in the placebo group were attributed to adverse events. The most common adverse events causing topiramate discontinuation were “difficulty with memory not otherwise specified” (3% for topiramate vs 1% for placebo) and “depression” (2% for topiramate vs 1.5% for placebo). Paresthesia, taste perversion, upper respiratory tract infection, memory and concentration difficulties occurred significantly more frequently among the topiramate-treated participants than the placebo-treated subjects (see Table 1). Three patients in each group experienced serious adverse events. Serious adverse events reported in topiramate-treated patients included acute cholecystitis, major depression, and tibial fracture. Serious adverse events reported in placebo-treated patients included asthma exacerbation, “stomach virus,” and arrhythmia. One patient discontinued topiramate due to a clinically asymptomatic hyperchloremic acidosis, which was mild and resolved after drug discontinuation.

Claudino et alReference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15 performed a 21-week double-blind RCT against placebo among 73 outpatients. A run-in single blind placebo phase of 5 weeks was planned. If participants reported at least two binge episodes during the final week of the run-in phase, they were randomly assigned to topiramate plus CBT or placebo plus CBT. Topiramate was gradually increased over 25 to 300 mg/d with a mean dose of 205.8 mg/d. The topiramate effect on the extracted outcomes can be found in Table 2. Paresthesia, dysuria, taste perversion and leg pain occurred significantly more frequently among topiramate-treated participants. Dropout rates did not significantly differ between groups. No serious adverse events were reported during the trial.

Risk of bias of the included studies

Overall, a low risk of bias was found for two studies,Reference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 , Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 and there were some concerns for the third,Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15 see Supplementary Table S2.

Randomization Process: Two studies were judged at low risk.Reference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 , Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 In one study,Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15 there were some concerns with statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics of the participants, which raised concerns about the randomization process.

Deviation from intended interventions: All studies were judged at a low risk level.Reference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 , Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 , Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15

Missing outcome data: All studies were judged at a low risk level.Reference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 , Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 , Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15 Even if there were high rates of dropout, all studies provided detailed reasons for dropout, and all studies used an intention-to-treat approach with suitable analysis procedures aiming to correct for missing data. Moreover, the proportion of missing data were similar across groups within each study.

Measurement of the outcome: All studies were judged at a low risk level.Reference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 , Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 , Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15

Selection of the reported results: Two studies were judged at low risk.Reference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 , Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 In one study,Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15 there were some concerns because the primary outcome planned in the study protocol differed from that of the published study.

Meta-analysis results

Description within study of the outcomes

Efficacy of topiramate: Binge frequency, weight, and quality of life

As shown in Figure 1, a larger reduction in the number of binge episodes per week, with a mean difference of 1.31 (95% confidence interval (CI) −2.58 to −0.03) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 94%), was found in the topiramate group than the placebo group. The topiramate participants also showed a mean reduction in the number of binge days per week, with a mean difference of 0.98 (95% CI −1.80 to −0.15) and high heterogeneity (I 2 = 94%) (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Forest plot for binge episodes per week

Figure 2. Forest plot for binge days per week.

Finally, on a two-study meta-analysis including one with a wide CI, topiramate participants had higher weight loss compared to placebo participants, with a mean difference of −4.91 kg (95% CI −6.42 to −3.41; I 2 = 10%) (Figure 3). Quality of life was assessed only in one RCT.Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6

Figure 3. Forest plot for weight loss.

Other efficacy outcomes: obsessive compulsive symptoms and depression

The depression scores at the final visit were provided in two studies, with two different scales (Beck Depression Inventory and Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale). Topiramate did not have a significant effect on depression scores (standardized mean difference, SMD = −0.01; 95% CI −0.29 to 0.27; I2 = 35%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Forest plot for depression scores.

Impulsivity was reported in only one study.Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 Obsessive–compulsive symptoms were reported in two studies.Reference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 , Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 However, no data were available at the end of the study. These parameters were thus not amendable to meta-analysis.

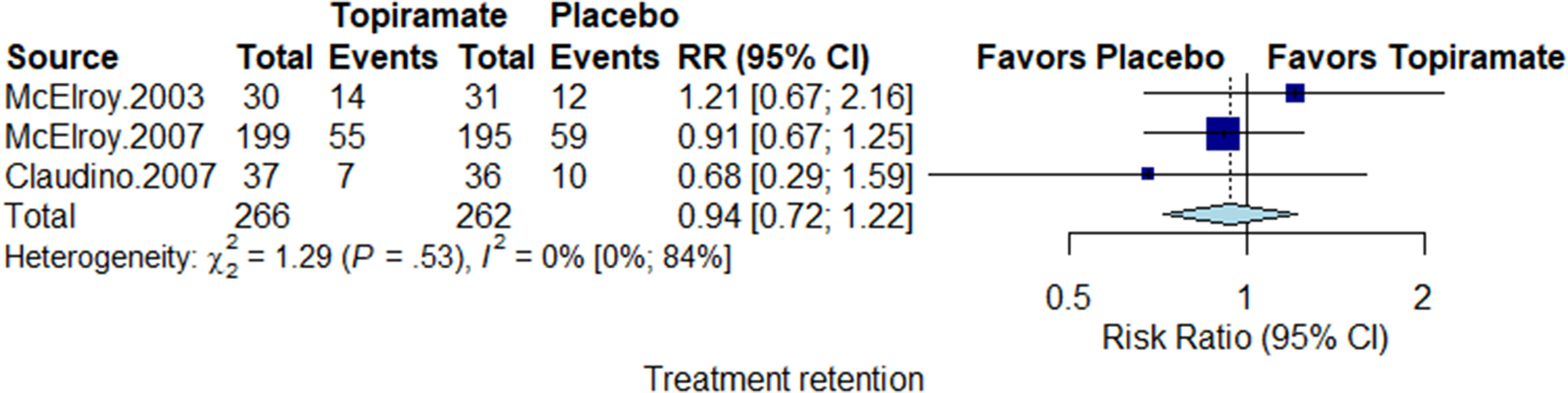

Treatment retention

Treatment retention was measured using participant dropout rates. All three studies assessed this parameter in a total of 528 participants, with a pooled result of 28% dropout for topiramate groups and 30% for placebo groups. The risk ratio of drop out was not significantly different between the topiramate and placebo groups, with a relative risk (RR) = 0.95 (95% CI 0.73-1.24) and no heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Forest plot for treatment retention

Safety outcomes

The three-study meta-analysis showed that topiramate participants had a higher risk of withdrawal because of an adverse event compared to placebo (RR = 1.90; 95% CI 1.13-3.18; I 2 = 0%) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Forest plot for dropouts due to adverse events.

Discussion

This meta-analysis was the first to investigate the efficacy of topiramate on the frequency of binge episodes and weight loss in patients with BED, as well as the safety-related parameters. Overall, we found that, compared to placebo, topiramate was associated with a significant reduction in the number of binge episodes per week and a significant reduction in the number of days with binge per week. Topiramate also induced a greater weight reduction than placebo. Quality of life was assessed in one studyReference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 and was thus not amendable to meta-analysis. The results of our meta-analysis on secondary outcomes were relatively limited. No effect was found on depression outcomes. Impulsivity and craving symptoms were not amendable to this meta-analysis.

Overall, the findings from our meta-analysis raise several comments. With regard to the results on binge frequency, we were not able to formally explain the heterogeneity because of the small number of studies. Claudino et alReference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15 mostly recruited females (95%), which can explain a part of the heterogeneity. Furthermore, they used CBT in both arms. In a previous meta-analysis,Reference Ghaderi, Odeberg and Gustafsson 16 CBT showed a high efficacy on binge frequency (SMD = −0.83). Adjunctive CBT could thus be a possible explanation for the heterogeneity found in the binge outcomes. The pooled effect size of the reduction in binge frequency could be considered small to moderate, although a reduction in one binge day per week may be an appreciable clinical result for some patients or clinicians. A qualitative evaluation of this reduction was not assessed in the included studies. This could be warranted for future trials.

Topiramate induced greater weight loss than placebo. However, we do not know if the weight loss with topiramate was related to the reduction in binge frequency and/or the reduction in appetite or a metabolic effect, as no assessment was made on these parameters in these studies. Similarly, topiramate has been found to reduce impulsivity in other additive disorders, such as alcohol dependence,Reference Rubio, Martínez-Gras and Manzanares 17 which might contribute to its effect on binge frequency. Another point is that we are not able to determine if the reduction in binge frequency was associated with an improvement in quality of life. Quality of life was improved in topiramate participants, compared to placebo participants, in one studyReference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 and was not assessed in two others.Reference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 , Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15 Regarding depression outcomes, topiramate was not found to improve depression scores more than placebo. Interestingly, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were also found to improve remission rates in BED, but without reducing depressive symptoms.Reference Ghaderi, Odeberg and Gustafsson 16

Overall, topiramate raised more safety concerns than placebo. Topiramate participants exhibited significantly more dropouts due to adverse events than placebo participants. Topiramate-treated participants reported significantly more adverse events, particularly more frequent paresthesia, taste perversion, and confusion.Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 , Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15 Three serious adverse events were found in the topiramate groups: acute cholecystictis, major depression, and tibial fracture. However, a difference in the occurrence of serious adverse events could be likely to appear in trials with longer durations and within larger samples. In 2008, the FDA edited the black box warning for anti-epileptic drugs. In particular, they reported that topiramate increased the risk of committing suicide by 2.53-fold.Reference Hernández-Díaz, Smith and Shen 18 However, other studies did not find an increased risk of suicidality with topiramate.Reference Patorno, Bohn, Wahl, Avorn and Patrick 19 , Reference Schuerch, Gasse and Robinson 20 Furthermore, in other fields, topiramate has been associated with increased myopia and increased intraocular pressure associated or not with angle closure glaucoma,Reference Symes, Etminan and Mikelberg 21 renal stones,Reference Dell’Orto, Belotti and Goeggel-Simonetti 22 metabolic acidosis,Reference Dell’Orto, Belotti and Goeggel-Simonetti 22 oligohydrosis,Reference Ziad, Rahi, Abu Hamdan and Mikati 23 , Reference Karachristianou, Papamichalis, Sarantopoulos, Boura and Georgiadis 24 major congenital malformations,Reference Tennis, Chan and Curkendall 25 related psychosis, 26-28 and sexual dysfunction.Reference Chen, Chen, Chen, Lin, Chien and Yin 29 By contrast, a majority of the previous meta-analyses on topiramate, including meta-analyses in other addictive disorders such as cocaine or alcohol use disorder, did not find an increased rate of adverse events in the topiramate group. 30-32 In these patients with BED, this could have been due to the dose ranges of topiramate used. Indeed, the maximum doses used in the BED studies reached 600 mg/d, whereas in other addictive disorders, the maximum dosing usually reached 300 mg/d. 33-36 A dose-effect relationship in the occurrence of adverse events was previously found in a meta-analysis.Reference Kramer, Leitão, Pinto, Canani, Azevedo and Gross 37 Similarly, an RCT in obesity without BED found that the cognitive impairment induced by topiramate was dose related, with significant risk thresholds at 192 and 384 mg/d.Reference Loring, Williamson, Meador, Wiegand and Hulihan 10 The titration schedule should also be noted. In alcohol use disorder, higher dropout rates in topiramate-treated patients were observed when the titration schedule was faster.Reference Johnson, Rosenthal and Capece 38 In other addictive disorders, the titration schedule was similar to that of BED with an escalating dose from 25 mg per day to maximum dosage (200-300 mg/d) over 6 to 8 weeks, and topiramate was not associated with an increased rate of dropout.Reference Singh, Keer, Klimas, Wood and Werb 31 , Reference Jonas, Amick and Feltner 39

The results presented in the present systematic review and meta-analysis should be considered with respect to several limitations. First, as previously mentioned, there was a small number of studies assessing topiramate in patients with BED with only three RCTsReference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 , Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 , Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15; three single armedReference Appolinario, Fontenelle, Papelbaum, Bueno and Coutinho 8 , Reference McElroy, Shapira and Arnold 9 , Reference Zilberstein, Pajecki, De Brito, Gallafrio, Eshkenazy and Andrade 40 and one unblinded comparative study of topiramate plus sertraline plus diet to sertraline plus diet or diet onlyReference Brambilla, Samek, Company, Lovo, Cioni and Mellado 7 were not included in the present meta-analysis because of study design (see inclusion/exclusion section). Second, only 528 patients were included in this meta-analysis, and only one study had a large sample size that could have most influenced the treatment effect.Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 Furthermore, the two positive studies were from the same U.S. team,Reference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5 , Reference McElroy, Hudson, Capece, Beyers, Fisher and Rosenthal 6 whereas the third and only negative study was from a small Brazilian sample,Reference Claudino, De Oliveira and Appolinario 15 which consisted of 90% females and received add-on CBT. Third, all studies excluded unstable psychiatric disorder and substance use disorder, which limits the generalization of the results. Fourth, quality of life was measured in only one study and thus could not be used as an additional meta-analytical outcome, although it is a very relevant outcome for measuring a treatment effect. We had trouble obtaining some data, even when the authors were contacted in multiple ways. Better and easier access to all the data may have facilitated and strengthened the implementation of the meta-analysis. Moreover, the lack of standardization of outcomes across studies makes it difficult to pool all extracted data on our outcomes of interest. The adoption of core outcome sets, best standards in reporting and availability of individual patient data 41 are expected to overcome this problem in the future. Fifth, we did not have SD for the mean change in binge days per week and binge days in one trialReference McElroy, Arnold and Shapira 5; thus, we imputed the most conservative SD values from the p values of the Wilcoxon test according to the Cochrane recommendation (http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/).

Conclusions

There is some evidence supporting topiramate efficacy in reducing binge frequency and weight in patients with BED with small effect sizes. High heterogeneity and a limited number of studies with small sample sizes make it difficult to judge the actual effect size. In addition, it is still uncertain that these benefits assessed in short-term trials translate to longer-term health outcomes. In addition, the tolerability profile of topiramate could limit its use. Therefore, our findings will not change clinical routine in BED. However, it emphasizes the need to perform more RCTs comparing topiramate and placebo in BED. Quality of life should be an outcome included in future RCTs.

Author Contributions

B.R. and M.C. designed the research; M.N. and L.J. performed the research; M.N. and M.C. analyzed the data. M.N., M.C., and B.R. wrote the first draft of manuscript; all the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosures

G.G. has received support for travel to scientific meetings from Novo Nordisk, and Lilly. B.R. has received lecture fees from Janssen-Cilag. M.N., L.J., M.A., B.K., M.C., and S.I. declare having no conflict of interest.