Introduction

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) are revising DSM-IV and ICD-10. The existing classification systems use symptom profiles as defining principles. The DSM-V Task Force and ICD-11 Nosology Groups are discussing whether it is possible to recognize the possibility of common aetiological pathways. A DSM-V Study Group charged with this responsibility identified 11 possible validating criteria that could be used to define groups of disorders with common risks and clinical manifestations (Hyman et al., personal communication, 3 December 2007). These are:

(1) genetic factors;

(2) familiality;

(3) early environmental adversity;

(4) neural substrates;

(5) biomarkers;

(6) temperamental antecedents;

(7) cognitive and emotional processing;

(8) differences and similarities in symptomatology;

(9) co-morbidity;

(10) course;

(11) treatment.

The proposed validators continue to recognize the traditional diagnostic importance of clinical manifestations but also incorporate the potential causes of the disorder. Reviews of the literature found that such groupings are possible. These reviews propose a meta-structure of DSM-V and ICD-11 that may increase the validity and clinical utility of the forthcoming diagnostic systems (Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Goldberg, Krueger, Carpenter, Hyman, Sachdev and Pine2009a, Reference Andrews, Pine, Hobbs, Anderson and Sunderlandb; Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Bustillo, Thaker, van Os, Krueger and Green2009; Goldberg et al. Reference Goldberg, Krueger, Andrews and Hobbs2009; Krueger & South, Reference Krueger and South2009; Sachdev et al. Reference Sachdev, Andrews, Hobbs, Sunderland and Anderson2009). It is suggested that five clusters, namely neurocognitive, neurodevelopmental, psychosis, emotional and externalizing, could replace many of the existing 16 DSM and 10 ICD chapters. However, the cluster membership of bipolar disorder (BPD) may prove controversial.

Currently, BPD is classified with the ‘Mood Disorders’ in both DSM-IV and ICD-10. However, there has been growing debate regarding whether BPD could be better classified alongside schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. If only the clinical features of BPD are considered, it is difficult to place in a meta-structure because it shares obvious state-related clinical similarities with unipolar depression (UPD), yet mania overlaps clinically with schizophrenia. This suggests that, at the symptom level, BPD shares some similarities with both the emotional and psychosis clusters of the proposed meta-structure. In terms of both risk factors and clinical manifestations, however, does BPD have more similarities with the psychosis or the emotional cluster? There are three possible solutions to the problem: having a separate cluster, considering BPD with the psychoses or including the former with the emotional disorders. The latter would be the least contentious solution and the purpose of this paper is to consider the evidence that might inform cluster membership.

Method

This paper assumes that the correct cluster membership of UPD and schizophrenia is with the emotional disorders and psychoses respectively. Given that there are no data regarding the cluster membership of BPD in clusters defined in this way, this paper addresses the arguments for the most appropriate placement of BPD.

Scopus, EMBASE, PsychINFO and Medline searches were conducted to identify English-language articles and reviews of schizophrenia, BPD and UPD that considered the risk associated with each validating criterion. Epidemiological and clinical data were considered for inclusion. Specialist data were more heavily relied on, where population studies have not provided data on these disorders and the respective criteria.

Results: differences and similarities between schizophrenia, BPD and UPD in terms of the 11 validators

Genetic factors

Genomic screens have identified no specific genes that cause UPD, BPD or schizophrenia (for reviews see Crow, Reference Crow2007; Hettema, Reference Hettema2008). Nevertheless, twin data have confirmed the role of genetic risk factors in all three disorders. Jones et al. (Reference Jones, Kent, Craddock, McGuffin, Owen and Gottesman2002) review six twin studies of BPD that show undoubted evidence of genetic factors in its aetiology. Bertelsen et al. (Reference Bertelsen, Harvald and Hague1977) and McGuffin et al. (Reference McGuffin, Rijsdijk, Andrew, Sham, Katz and Cardno2003) report two twin studies that confirm substantial genetic influences in both BPD and UPD but also show an increased concordance rate for UPD in the monozygotic (MZ) bipolar probands. The latter study rejects a model where bipolarity is seen as a more severe form of depression, in favour of a model where there are two correlated liabilities. They concluded that 71% of the genetic variance for mania is not shared with depression. However, modest evidence has been found that BPD and UPD represent a single genetic continuum (Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Pedersen, Neale and Mathe1995).

If the tendency to have manic symptoms is thought of as an underlying dimension of ‘mania’, then ‘BPD-II’ is a less severe degree of this dimension, which is itself related to two other dimensions: one for schizophrenia and the other for depression. A twin study by Cardno et al. (Reference Cardno, Rijsdijk, Sham, Murray and McGuffin2002) showed a shared genetic susceptibility to mania, schizophrenia and schizo-affective disorder. Owen et al. (Reference Owen, Craddock and Jablensky2007) reviewed the evidence for familial and genetic overlap between BPD and schizophrenia, and speculate that there are three overlapping groups of genes, relating to schizophrenia, psychosis (delusions and hallucinations) and depression. The psychosis genes overlap with both the other groups, but the genes for schizophrenia and BPD are specific to each, thus partially validating the Kraepelinian dichotomy. Lichtenstein et al. (Reference Lichtenstein, Yip, Bjork, Pawitan, Cannon, Sullivan and Hultman2009) have confirmed these views by showing clear evidence of shared genes between schizophrenia and BPD in a study of 9 million individuals in more than 2 million families.

The genes for UPD, however, are similar or identical to those for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and overlap with most of the other emotional disorders (e.g. Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Prescott, Myers and Neale2003). Nonetheless, there is an increased expectancy of UPD in co-twins of MZ BPD of between 15% and 25%, which would support a relationship between the two (Craddock, Reference Craddock1995). Overall, the findings can be summarized by saying that there is overlap in each direction, and probably favours a separate but related cluster without being conclusive.

Familiality

Familial studies indicate the aggregation of related disease within family-related probands; thus, it is presumed that disorders within clusters will have higher rates and patterns of aggregation than those between clusters. Taylor (Reference Taylor1992) showed that first-degree relatives of probands with BPD have an increased risk of developing BPD, schizo-affective disorder and UPD. In general, studies of familiality have shown a substantially increased risk of UPD in families of BPD probands; indeed, the absolute risk of UPD is greater than that for BPD, although the relative risk for UPD is approximately double. However, Blacker & Tsuang (Reference Blacker and Tsuang1993) have speculated that three-quarters of these unipolar relatives of bipolar probands may be ‘genetically bipolar’. The issue is unresolved.

An important study of familiality was reported by Winokur et al. (Reference Winokur, Coryell, Keller, Endicott and Leon1995) as part of the Collaborative Depression Study in which more than 900 depressed patients were examined at five participating clinical centres. Healthy community controls (HC) and their relatives were also interviewed. Familial BPD-I or schizo-affective mania were found to be significantly higher in the first-degree relatives (FDRs) of probands with BPD-I or schizo-affective mania than in FDRs of subjects with primary UPD, who were themselves no different from HC in this respect. Winokur et al. then separated the probands into a severe BPD group with psychotic features and a less severe group with non-psychotic BPD. They found no difference in the amount of total affective disorder or mania between these groups in the family members. This suggests that, within the BPD diagnosis, there is no severity continuum of familiality. They concluded that the evidence supports the idea that BPD-I is an independent illness.

Expectancies are different in UPD. McGuffin et al. (Reference McGuffin, Katz and Bebbington1987) reviewed the literature, which clearly shows that although the expectancies of UPD are increased and approximately equal, in the relatives of both BPD (11.4%) and UPD (9.1%) probands, the risk for BPD is only increased among the relatives of bipolar patients (7.8% v. 0.6%).

In another important study Mortensen et al. (Reference Mortensen, Pedersen, Melbye, Mors and Ewald2003) analysed 2299 Danish patients with bipolar affective disorder. Parental and sibling bipolar schizo-affective disorder increased the risk of BPD in the proband very much more than parental/sibling recurrent depression. Parental schizophrenia or recurrent depression increased the risk of BPD to about the same extent, but much less so than schizo-affective disorder. Children who experienced maternal loss before their fifth birthday had a greatly increased risk of bipolar affective disorder.

The tendency of the manic form of schizo-affective illness to cluster with BPD rather than schizophrenia has been confirmed by several studies (Maier et al. Reference Maier, Lichterman, Minges, Hallmayer, Heun, Benkert and Levinson1993; Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Karkowski and Walsh1998). Andreasen et al. (Reference Andreasen, Rice and Endicott1987), however, showed that depressed schizo-affective probands had higher rates of schizophrenia than relatives of bipolar schizo-affective patients. These studies have not found a substantial elevation of rates for schizophrenia in families of BPD probands. However, Lichtenstein et al.'s (Reference Lichtenstein, Yip, Bjork, Pawitan, Cannon, Sullivan and Hultman2009) analyses of FDRs of 35 985 probands with schizophrenia and 40 487 probands with BPD showed that there were elevated rates of each disorder in the families of patients with the other; this being a study with most power to study such phenomena. Although 30–40% of the genetic risk is common between them, each also has unique genetic effects. The authors conclude ‘these results challenge the current nosological dichotomy between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and are consistent with a reappraisal of these disorders as distinct diagnostic entities.’

On balance, the evidence strongly supports a distinction between BPD and UPD, but also supports a distinction between BPD and schizophrenia, with different forms of schizo-affective illness uneasily divided between the two.

Early environmental adversity

Geddes et al. (Reference Geddes, Verdoux, Takei, Lawrie, Bovet, Eagles, Heun, McCreadie, McNeil, O'Callaghan, Stober, Willinger and Murray1999) conducted a meta-analysis of 700 schizophrenia patients and concluded that hypoxia may play a role in its aetiology. Similarly, Cannon et al. (Reference Cannon, Rosso, Hollister, Bearden, Sanchez and Hadley2000), using prospective-longitudinal data, reported that the odds ratios (ORs) of schizophrenia increased linearly with increasing number of hypoxic events. An increased number of perinatal insults has also been associated with UPD with a childhood onset (before age 15 years) when compared to those with an onset in adult life (Jaffee et al. Reference Jaffee, Moffitt, Capsi, Fombonne, Poulton and Martin2002). On the other contrary, BPD has been consistently found not to be associated with perinatal insults such as hypoxia (for a review see Murray et al. Reference Murray, Sham, Van Os, Zanelli, Cannon and McDonald2004).

The evidence regarding early parental loss as a predictor of UPD, BPD and schizophrenia is slightly conflicting. Alnaes & Torgerson (Reference Alnaes and Torgersen1993) found that out-patients with UPD reported more traumatic childhood events than those with BPD. Furukawa et al. (Reference Furukawa, Ogura, Hirai, Fujihara, Kitamura and Takahashi1999) compared the remembered childhood experiences concerning parental death or separation before age 16 between groups of BPD and UPD patients and HC. Whereas the BPD patients were no more likely to have experienced this than the controls, there was an excess among the UPD patients. Other studies conclude that early parental loss is a non-specific predictor of UPD, BPD and schizophrenia, with all disorders experiencing more loss than controls (Agid et al. Reference Agid, Shapira, Zislin, Ritsner, Hanin, Murad, Troudart, Bloch, Heresco-Levy and Lerer1999; Laursen et al. Reference Laursen, Munk-Olsen, Nordentoft and Mortensen2007). However, Agid et al. (Reference Agid, Shapira, Zislin, Ritsner, Hanin, Murad, Troudart, Bloch, Heresco-Levy and Lerer1999) report that, when compared to non-depressed controls, UPD had marked effects before age 8, with loss by separation being worse than loss by death. There were no significant effects in any of the subcategories in cases of BPD (death, separation, age group), so the effect seems to be weaker than in UPD. Van Os et al. (Reference Van Os, Jones, Sham, Bebbington and Murray1998) in a review of the environmental risks of schizophrenia and affective psychoses concluded that the environmental risks of these disorders, including adverse life events and familial risk, differed in terms of quantity rather than quality. The evidence suggests that UPD, BPD and schizophrenia share childhood histories of disruptive environments. It is expected that this risk is common among several disorders as a shared liability to mental illness and thus it provides only weak evidence for cluster membership. In summary, there are clear differences between UPD and BPD, but also between BPD and schizophrenia.

Neural substrates

At a functional level, individuals with UPD show greater similarity to HC than individuals with BPD. Early studies showed this by examining whole-brain metabolic rate (Baxter et al. Reference Baxter, Phelps, Mazziotta, Schwarz, Gerner, Selin and Sumida1985). Unique to remitted subjects with BPD is increased cerebral blood flow in the dorsal anterior cingulate with mood induction, the reverse of what is reported in remitted subjects with UPD (Liotti et al. Reference Liotti, Mayberg, McGinnis, Brannan and Jerabek2002; Krüger et al. Reference Krüger, Seminowicz, Goldapple, Kennedy and Mayberg2003).

Phillips et al. (Reference Phillips, Drevets, Rauch and Lane2003) argue that there are structural differences between BPD and UPD, and that these are related to functional differences between them. In BPD, enlarged amygdalar volumes and increased ventral system activity suggest a dysfunctional increase in the sensitivity of this system to emotionally significant stimuli and the production of affective states. However, in UPD there are volume reductions within the amygdala and other components of the ventral neural system. The increased rather than decreased activity within these regions during illness may result in a restricted emotional range, biased towards the predominant role of the amygdala in the perception of negative rather than positive emotions.

More recently, Konarski et al. (Reference Konarski, McIntyre, Kennedy, Rafi-Tari, Soczynska and Ketter2008) reviewed 140 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies, and concluded that whole-brain volumes of patients with either mood disorder do not differ from those of HC. The ventricles are enlarged in BPD, whereas the subcortical structures, particularly the striatum, amygdala and hippocampus, may be differentially affected in UPD and BPD.

Using the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) binding potential assessed with positron emission tomography (PET), Cannon et al. (Reference Cannon, Ichise, Rollis, Klaver, Gandhi, Charney, Manji and Drevets2007) showed reduced activity in BPD relative to both HC and UPD groups in the vicinity of the pontine raphe nuclei. By contrast, UPD had elevated activity relative to both BPD and HC groups in the vicinity of the periaqueductal grey matter.

Phillips & Vieta (Reference Phillips and Vieta2007) argue that functional abnormalities in neural systems underlying emotion processing (amygdala centred, dealing with mood instability), working memory and attention (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex centred, dealing with cognitive control processes) persist in BPD remission, and are BPD specific rather than common to UPD.

A comparison between the neural substrate in schizophrenia and BPD is described in detail in the companion paper by Carpenter et al. (Reference Carpenter, Bustillo, Thaker, van Os, Krueger and Green2009) and in a recent review by McDonald (Reference McDonald and McDonald2008). It can be summarized by saying that, although there are some similarities between the disorders (both have grey matter deficits, albeit in different distributions, both have neuronal dysfunction and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) ergic indices in hippocampus and cingulate), there are also important differences (reduced prefrontal grey matter volumes, in schizophrenia only, and opposite changes in both the amygdale and the hippocampus. White matter deficits are overlapping but most marked in schizophrenia, particularly in the posterior corpus callosum and the left frontal and temporoparietal regions). In summary, the evidence favours BPD being clearly distinguishable from both schizophrenia and UPD.

Biomarkers

Biomarkers identified in abnormal cognitive processing is the identifying feature of the psychosis cluster; these include smooth pursuit eye movement abnormalities, sensory gating deficits (P50), prepulse inhibition and P300 evoked potential abnormalities. The majority of these abnormalities are not commonly associated with UPD or other emotional disorders but all are associated with BPD (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Bustillo, Thaker, van Os, Krueger and Green2009). Nevertheless, Roschke et al. (Reference Roschke, Wagner, Mann, Fell, Grozinger and Frank1996) report P300 abnormalities in UPD. Other biomarkers, including sleep abnormalities, are seen in all three disorders, so that the ‘clock’ biomarkers described by Bunney & Bunney (Reference Bunney and Bunney2000), and later by others, do not seem to help to discriminate between the three groups.

Currently, there is a lack of literature that provides a systematic comparison of UPD and BPD on these biomarkers. In the absence of contrary evidence, it seems that the commonality of BPD biomarkers to the psychosis cluster provides some support to membership of the psychosis cluster.

Temperamental antecedents

Negative affect (neuroticism) is one of the cardinal features of the emotional disorders but is not a marked feature of BPD. It has been shown to precede episodes of depression (Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Neale, Kessler, Heath and Eaves1993) whereas in disorders in other clusters the measurement has been made after onset of the disorder in question. An early paper by Clayton et al. (Reference Clayton, Ernst and Angst1994) showed that Swiss men who developed UPD had higher scores than those developing BPD in terms of autonomic lability, a constellation of traits that correlated highly with neuroticism. The BPD men did not differ from controls on any occasion of testing. Akiskal et al. (Reference Akiskal, Kilzieh, Maser, Clayton, Schettler, Traci Shea, Endicott, Scheftner, Hirschfeld and Keller2006) and Tackett et al. (Reference Tackett, Quilty, Sellbom, Rector and Bagby2008) found that BPD-I are quantitatively more neurotic than HC, but much less so than UPD. Akiskal et al. (Reference Akiskal, Kilzieh, Maser, Clayton, Schettler, Traci Shea, Endicott, Scheftner, Hirschfeld and Keller2006) also show that neuroticism scores are even higher in BPD-II, significantly more so than UPD. They further find that UPD and BPD-II are significantly more introverted than either BPD-I or HC. Cyclothymic personality is more common in both BPD-I and BPD-II than in UPD. Cuellar et al. (Reference Cuellar, Johnson and Winters2005) also argue in their comprehensive review that, within the group of BPD patients, neuroticism is associated with increasing depression over time but is unrelated to manic symptoms. They assert that it has consistently been shown that neuroticism is the personality variable most associated with UPD. In summary, there are clear differences between UPD and BPD, but also lesser differences between BPD and schizophrenia (see Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Bustillo, Thaker, van Os, Krueger and Green2009).

Cognitive and emotional processing

Wolfe et al. (Reference Wolfe, Granholm, Butters, Saunders and Janowsky1987) compared BPD and UPD patients on verbal fluency and verbal learning tasks, and showed that BPD patients are more handicapped than UPD patients. The UPD group was intermediate between the BPD and the HC groups. Summers et al. (Reference Summers, Papadopoulou, Bruno, Cipolotti and Ron2006) compared BPD-I and BPD-II patients using a cognitive battery and a facial emotion recognition task. They showed that BPD-I patients were impaired compared to published norms on memory, naming and executive measures, whereas cognitive performance was largely unrelated to depression ratings. This study also provides evidence that cognitive deficits are more severe and pervasive in BPD-II patients, suggesting that recurrent depressive episodes, rather than mania, may have a more detrimental and lasting effect on cognition. In their review of the field, Phillips et al. (Reference Phillips, Drevets, Rauch and Lane2003) argue that different neural structures are responsible for the differences in the disorders' cognitive and emotional processing. In BPD, findings suggest a dysfunctional increase in the sensitivity of the neural system to identify emotional significance and produce affective states. The authors also speculate that impaired effortful regulation of subsequent emotional behaviours may result from decreases in prefrontal cortical volumes and activity within the dorsal system. However, in UPD they suggest that the pattern of reduced volume and increased ventral system function indicates a bias of this system towards identifying specifically negative material.

Borkowska & Rybakowski (Reference Borkowska and Rybakowski2001), using a set of neuropsychological assessments, showed greater frontal impairment in BPD relative to UPD. They concluded that their results corroborated other findings indicating pathogenic distinctions between BPD and UPD, and some similarities between BPD and schizophrenia. Lawrence et al. (Reference Lawrence, Williams, Surguladze, Giampietro, Brammer, Andrew, Frangou, Ecker and Phillips2004), using functional MRI responses to faces with various emotions, found that, in comparison to UPD and HC, patients with BPD had increased subcortical and ventral prefrontal cortex responses to both positive and negative emotional experiences. These differences were not state related, suggesting that the differences are disorder specific. In summary, there are clear differences between BPD and UPD, and some similarities between BPD and schizophrenia, described in the companion paper (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Bustillo, Thaker, van Os, Krueger and Green2009).

Differences and similarities in symptomatology

Although the diagnostic requirements for mania are distinct from those for schizophrenia, the psychotic symptoms of mania largely overlap with many of what were once called ‘first rank’ symptoms of schizophrenia (Brockington & Leff, Reference Brockington and Leff1979). Although readily distinguishable in their pure forms, there are few pathognomonic symptoms that clinicians can use to distinguish them, and intermediate forms undoubtedly exist. Furthermore, the symptoms of BPD (depressed) largely overlap with those of UPD. Mitchell et al. (Reference Mitchell, Goodwin, Johnson and Hirschfeld2008) claim that there are differences that, taken together, might allow episodes of UPD to be distinguished from BPD, but the study needs replication. Forty et al. (Reference Forty, Smith, Jones, Caesar, Cooper, Fraser, Gordon-Smith, Hyde, Farmer, McGuffin and Craddock2008) in a large comparison of BPD-I and UPD found that psychotic symptoms, diurnal mood variation and hypersomnia during an episode of, and increased number of, depressive episodes increased the risk of BPD compared with UPD.

It is suggested that these symptom similarities and differences are surface indicators of mental disorders and should not determine cluster membership. Nevertheless, as a validator, the commonality of some core depressive symptoms to both UPD and BPD, and psychotic symptoms between mania and schizophrenia, once more favour a separate cluster.

Co-morbidity

BPD is co-morbid with numerous other disorders; indeed co-morbidity is the rule, not the exception (see standard texts, e.g. Gelder et al. Reference Gelder, Lopez-Ibor and Andreasen2000, p. 696). In the German National Study, for example, BPD occurred on its own in only 25.7% of all cases of BPD found, but with one additional diagnosis in 24.6%, with two in 14.9%, and with three or more in 34.9%. Although these figures may look striking, they must be compared with those for depressive disorder, which are 39.3, 20.8, 15.8 and 24.1% respectively (Jacobi et al. Reference Jacobi, Wittchen, Holting, Hofler, Pfister, Muller and Lieb2004). To show a difference between BPD and UPD, it is necessary to show that co-morbidity is greater in BPD than it is in UPD; and here the figures are very different. In the Australian National Mental Health Survey of 10641 individuals, the figures in the first column of Table 1 confirm that BPD is indeed co-morbid with a wide range of disorders, excluding only agoraphobia. However, the figures in the second column show that the relative odds between BPD and UPD are greater only for substance use (Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Slade and Andrews2004). This study also showed that BPD was distinguished from UPD in terms of a more equal gender ratio; a greater likelihood of being widowed, separated or divorced; greater disability as measured by days out of role; increased rates of treatment with medicines; and higher lifetime rates of suicide attempts. In the Zurich co-morbidity study, Merikangas et al. (Reference Merikangas, Herrell, Swendsen, Rössler, Ajdacic-Gross and Angst2008) confirm that BPD is co-morbid with a wide range of substance use disorders, whereas UPD only predicted benzodiazepine abuse. Studies have also reported high co-morbidity between BPD and eating disorders (e.g. Passino & Perugi, Reference Passino and Perugi2005; Wildes et al. Reference Wildes, Marcus and Fagiolini2008), but because the co-morbid rates were not contrasted with those for UPD, the matter is unresolved.

Table 1. Australian National Survey: odds ratios of co-morbid DSM disorders of those with BPD versus the rest of the sample, and BPD versus UPD (from Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Slade and Andrews2004)

BPD, Bipolar disorder; UPD, unipolar depression; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Significant odds ratios shown in bold type.

* p<0.05, ** p<0.001.

It is anticipated that co-morbidity rates will be greater within clusters than between clusters. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication is the largest general population survey using hierarchy-free DSM diagnoses measuring co-morbidity between major depression (UPD) and mania/hypomania (BPD) (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Chiu, Demler and Walters2005). Table 2 shows that there is somewhat higher co-morbidity for UPD with GAD, phobias, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and most of the other disorders in the emotional cluster than for BPD, which tends to be co-morbid with the externalizing disorders, including oppositional defiant disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance abuse. Angst & Gamma (Reference Angst, Gamma, Goldberg, Kendler, Sirovatka and Regierin press) report that co-morbidities between BPD-I and GAD are higher than those between UPD and GAD, and this has also been found in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (Merikangas et al. Reference Merikangas, Akiskal, Angst, Greenberg, Hirschfeld, Petukhova and Kessler2007). The co-morbid relationship between BPD and the externalizing disorders has also been found by Krüger et al. (Reference Krüger, Cooke, Hasey, Jorna and Persad1995) and Strakowski et al. (Reference Strakowski, McElroy, Keck and West1994). Both studies find co-morbidity between BPD and borderline personality disorder; although neither report data concerning UPD co-morbidity with the latter. Soreca et al. (Reference Soreca, Frank and Kupfer2009) point out that there is far more to BPD than mood instability, and draw attention to disturbances of circadian rhythms and cognitive impairment. The extremely high rate of co-morbidity between symptoms of schizophrenia and BPD is exemplified by the diagnostic category of schizo-affective disorder (Malhi et al. Reference Malhi, Green, Fagiolini, Peselow and Kumari2008). In summary, the evidence is conflicting, but to some extent it favours a separate cluster because BPD is co-morbid with similar disorders to UPD, albeit to a lesser extent, but is also substantially co-morbid with the psychoses.

Table 2. Tetrachoric correlations between major depression (UPD) and mania/hypomania (BPD) in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication

UPD, Unipolar depression; BPD, bipolar disorder; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Values given are 12-month rates in all cases; substantially higher correlations shown in bold (data from Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Chiu, Demler and Walters2005).

Course

Compared with UPD, BPD is reported to be associated with an age of onset 6 years earlier (Weissman et al. Reference Weissman, Bland, Canino, Fravelli, Greenwald, Hwu, Joyce, Karam, Lee, Lellouch, Lepine, Newman, Rubio-Stipec, Wells, Wickamaratne, Wittchen and Yeh1996; Solomon et al. Reference Solomon, Leon, Coryell, Mueller and Posternak2003; Jacobi et al. Reference Jacobi, Wittchen, Holting, Hofler, Pfister, Muller and Lieb2004), more frequent episodes, and greater short-term mood variability. No consistent differences have been found between episode length, some finding little difference between them (e.g. Coryell et al. Reference Coryell, Andreasen, Endicott and Keller1987) and others suggesting a shorter episode length of BPD compared to UPD (Roy-Byrne et al. Reference Roy-Byrne, Post, Uhde, Porcu and Davis1985; Furukawa et al. Reference Furukawa, Konno, Morinobu, Harai, Kitamura and Takahashi2000). Depression severity seems to be comparable between them, although the gender ratio of UPD usually shows a female preponderance, whereas that for BPD is approximately equal. Within the psychoses cluster, schizophrenia is more likely to lead to organic impairments and less likely to pursue a cyclical course than BPD; and BPD is more likely to lead to them than UPD. These findings lead to no firm conclusion, but to some extent they favour a separate cluster.

Treatment

There are obvious differences in pharmacological treatment that will not be elaborated on, except to say that mood stabilizers and neuroleptics have only a very limited place in UPD, although they are both used in BPD. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the first treatment of choice in UPD, may precipitate episodes of mania in UPD; although Chun & Dunner (Reference Chun and Dunner2004) claim that this risk has been overstated. Sachs et al. (Reference Sachs, Nierenberg, Calabrese, Marangell, Wisniewski, Gyulai, Friedman, Bowden, Fossey, Ostacher, Ketter, Patel and Hauser2007) report a large prospective randomized control trial that compared the use of standard antidepressant medication plus mood stabilizers versus mood stabilizers plus placebo in patients with bipolar depression followed for up to 26 weeks. Adjunctive antidepressant therapy was not associated with increased periods of euthymia or with an increased risk of treatment-emergent mania. However, monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors have been advocated in the treatment of anergic BPD (Himmelhoch et al. Reference Himmelhoch, Thase, Mallinger and Houck1991; Thase et al. Reference Thase, Mallinger, McKnight and Himmelhoch1992).

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment in UPD, and has also been adapted for BPD. Although some features are similar, the aims of treatment are substantially different. Rea et al. (Reference Rea, Miklowitz, Tompson, Goldstein, Hwang and Mintz2003) demonstrate that family-focused psycho-educational therapy was superior to individually focused patient treatment of manic patients in terms of frequency of new episodes over the next 2 years.

Conclusions

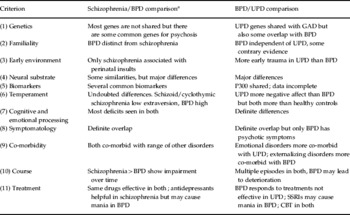

Bipolar illness clearly forms a fairly close tie between mania and schizophrenia, and another between bipolar depression and UPD. In this sense it could be viewed as an independent cluster, and the genetic, family data, neural substrate and temperament validators all clearly favour this solution to the problem. In addition, there are differences, albeit weaker ones, between BPD and schizophrenia in early environmental adversities, biomarkers and course (see Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of main similarities and differences over the 11 validators

BPD, Bipolar disorder; UPD, unipolar depression; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; CBT, cognitive behaviour therapy.

a See also Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Bustillo, Thaker, van Os, Krueger and Green2009.

However, if real differences between schizophrenia and BPD are acknowledged, it is still possible to think of them falling within a psychotic cluster. Delusions and hallucinations are shared between them, and although high negative affect characterizes the emotional cluster, it is not a marked feature of either of the psychoses. In this formulation, schizophrenia and BPD are looked upon as being at different ends of a psychosis continuum, with neural abnormalities, birth trauma and negative symptoms at one end, and affective symptoms and a somewhat better outcome at the other; differences between them are seen as quantitative, rather than each being a discrete disease entity (Van Os et al. Reference Van Os, Jones, Sham, Bebbington and Murray1998; Murray et al. Reference Murray, Sham, Van Os, Zanelli, Cannon and McDonald2004).

It is noteworthy that only symptom similarity (of depressive symptoms) supports BPD and UPD being together, but even here the existence of manic symptoms makes this solution unacceptable. There was a time when yellow jaundice and anaemia were both seen as single disorders; we now recognize that there are different causes of these epiphenomena. The phenomenon of depression is also like that; it can be caused by the possession of mania genes in addition to the genes responsible for emotional disorders, or it can be caused by negative affect (itself a product of distress genes and adverse early experiences). In both cases, vulnerability to developing depression follows adverse experiences in adult life. It is this complex interplay between two sets of genes and early life experience that makes depression more complicated than either jaundice or anaemia. But there are two sets of causes, and it is time our classification responded to them appropriately.

Acknowledgements

We thank T. M. Anderson and M. Sunderland for assisting with the literature searches.

Declaration of Interest

None.