INTRODUCTION

Law is an information intensive profession which requires lateral thinking - no single information source is comprehensive and the quantity of information useful to legal practitioners is not finite. Lawyers have complex legal problems to solve and it is the librarian's role to anticipate those needs well in advance of when lawyers think they will need to solve them. From 1641 onwards Middle Temple librarians have built a comprehensive, all-encompassing law library that represents the very best the Inn has to offer members of the Bar. The provision of authoritative resources in a timely manner means that Middle Temple Library plays a vital part in the administration of justice through its support of scholarship, legal education and the rule of law.

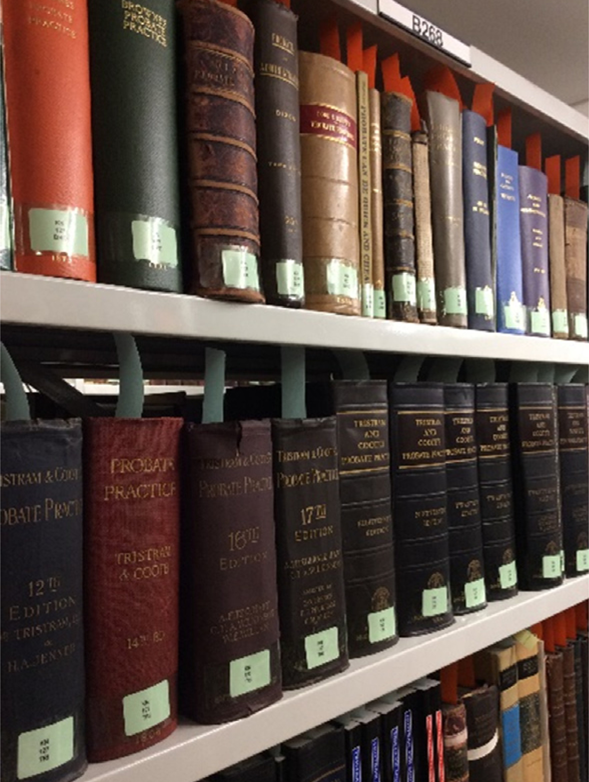

A fundamental aspect of the Inn's provision of information resources is immediate access to superseded legal resources, which allows members to research obscure points of law or carry out point-in-time research. Each individual resource (print and electronic) has a finite scope. The Inns of Court libraries provide access to materials ‘just in case’ they are required - the librarians anticipate members’ research needs based on our expertise in legal research.

Despite this, in late 2019 the library was informed by the Inn that our basement storage facility was going to be transformed into a members’ lounge. We were officially given three and a half months’ notice to vacate over 3km worth of books from the store. There was little room within the existing building to accommodate this amount of material.

We decided at the start to use an Agile approach to manage the project to ‘empty the basement’. The main components of the project involved moving books into a commercial, third party off-site storage facility; re-arranging and moving approximately 50% of the collection within the library in order to make better use of the space; installing new shelving wherever possible (e.g. in offices and on the landings) and moving books from the basement onto them; and de-accessioning some non-legal materials which accounted for approximately 20% of the collection.

In this article we discuss how we applied Agile project management techniques and tools to the project, and the pros and cons of adopting such an approach to complicated projects such as large-scale book moves.

AGILE: Renae Satterley

Agile is a manifesto underpinning a project management approach that differs significantly from more hierarchical and structured project management methods, such as Gantt charts or waterfalls. It focuses on the interdisciplinary strengths of a team and works well in library projects where staff tend to be grouped by discipline and speciality and often work independently.

The Agile manifesto values: individuals and interactions over processes and tools; working software over comprehensive documentation; customer collaboration over contract negotiation; responding to change over following a plan.Footnote 1 The emphasis is on the values in bold, with those that follow nonetheless of value. There then follow twelve principles, including but not limited to: a focus on customer satisfaction; welcoming changing requirements; collaborative working patterns; trusting and supporting motivated staff to get the job done; face-to-face communication; self-organising teams; continuous attention to excellence; regular reflection with the team in order to adjust the processes as required.Footnote 2

While Agile was originally developed in software development, its values and principles apply well to a range of projects including, in this instance, a large-scale book move. As M.M. Stoddard et al. have pointed out, Agile is ‘an overarching framework’ within which there are methodologies that can be applied to complete projects in an Agile manner”.Footnote 3 These methodologies consist of a series of tools and techniques which are applied to the project. Methodologies include Scrum and Kanban. Techniques include self-managing teams; visualising workflows; using incremental work sequences (‘sprints’); iterative work; and daily brief catch-up meetings amongst others. In Scrum for example, progress is set into ‘to do’; ‘doing’; and ‘done’ stages. This enables the team to see at once what progress is being made on the project, and what tasks remain to be completed.

A traditional Scrum methodology relies on daily meetings where “each team member shares three pieces of information: what has been accomplished since the previous meeting, what will be accomplished before the next meeting, and what, if any, obstacles are impeding the work.”Footnote 4 Due to differing hours, timetables and responsibilities, our basement project did not implement this daily aspect of Scrum, but information was nonetheless shared at fortnightly meetings.

TRELLO

TrelloFootnote 5 is a web-based project board that can form part of a Kanban or Scrum methodology. There are other visualisation processes on the market that enable you to create project boards, such as Asana, Microsoft Planner, and Wrike amongst others. A physical whiteboard with post-it notes is a similar visualisation process. For this project we used Trello as it was free, easy to use, and devoid of advertising and pop-ups.

Our Trello board used the standard Scrum methodology of ‘to do’; ‘in progress’; and ‘done’ columns. The ‘to do’ column contained the high-level list of tasks and the ‘in progress’ column reflected what was currently being carried out. Each column consisted of a series of cards which in turn contained a list of tasks organised under a ‘checklist’. Every time a task was completed, the task could be checked off; it could also be amended, re-assigned, or a due date imposed on it. The cards were categorised and labelled, and descriptions added to remind the team of the overall purpose of that set of tasks.

Figure 1: Trello.

Team members, including temporary staff, and senior stakeholders, were added to the board. The cards were assigned deadlines and members to readily identify who was responsible for which task. Members could be messaged directly within the card, which not only notified them of tasks still to be completed but retained a record of the conversation being enacted on the part of that task; this was visible to everyone.

Trello allows users to upload documents, and link to web-based storage facilities such as Google Docs/Drive, Dropbox, etc. Using these tools ensure that a team always uses the same version of a document and obviates the need to continually upload amended documents or mistakenly overwrite changes. We did continue to use spreadsheets outside of Trello as well, but this was more from force of habit than necessity.

A Trello board is a flexible tool designed to respond to the changing needs of a project, and the cards and columns were amended as the project progressed. For example, it became apparent that those tasks which did not have to be completed by a certain date would have to be put on hold due to the March 2020 pandemic shutdown, so the relevant cards with their tasks were moved to a new column entitled ‘post-removal tasks’. These included tasks such as changing shelfmarks and cataloguing un-catalogued material. This list of cards contained tasks that were not time-sensitive but still needed to be completed to bring the project to its conclusion.

Using an Agile approach ensured that we were able to change and add tasks as required without creating too much upset to the project. When the first lockdown was imposed, we were able to adapt tasks quickly to work on the project remotely while retaining a visualisation of the overall project. It is not clear if using a waterfall or Gantt chart approach would have enabled us to adapt as easily and as immediately.

The adaptability of Agile also meant that we were able to quickly re-group when the project changed course as lockdown eased. The social distancing regulations required no more than four people in the basement at a time, requiring more time to organise, box and ship all the books. The project's timeline also changed, giving us less time to empty the basement. We were able to adapt the project, working with our Estates department, and employed contractors to box the books and move them into the Hall. Library staff then worked in ‘bubbles’ to re-box, label and ship the books to the off-site storage company. Simultaneously they de-accessioned books and continued to move books internally. Trello provided us with a steady vision of the project that all could consult simultaneously. When temporary staff came in from other departments to assist, by adding them as members we were able to provide them with an immediate overview and history of the project, assign them tasks directly on Trello, and enable them to work independently while nonetheless having continually updated information about the project. Those working remotely could also see what was happening, and what tasks remained to be done. Our board also became a permanent record of the project. If queries arose as to why/how certain decisions were made, we had a record of the reasoning behind it, the dates, and who was involved.

Some of the difficulty in using an Agile approach is its potentially chaotic nature when one is first introduced to it. Team members who prefer a more structured project management approach and reams of documentation may struggle to get to grips with such an approach, which relies on the initiative of individual team members to complete tasks, as well as their skills and intuition to know which tasks to complete first. As mentioned earlier, we also did not follow all the Scrum techniques, partly due to the nature of the project, and partly due to the changes imposed by the pandemic lockdown. Had time allowed, daily scrums would have helped alleviate some of these difficulties.

AGILE IN PRACTICE: Beth Flerlage

The Basement Project, a straightforward moniker we used, was announced my third day on the job at The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple. My main responsibility as an Assistant Librarian is to develop and acquire legal materials and resources pertaining to the jurisdiction of the United Kingdom for our members. The announcement of this restructure meant a reimagining of the collection, which had been curated over centuries by countless predecessors. The principles of the Agile method, flexibility and collaboration in particular, provided me with better support in tackling this project as a new starter, and to the temporary staff brought on board to assist.

An Exposition of the Laws Relating to the Women of England and The Care of the Insane and Their Legal Control were just a couple of the over 4,000 titles to review in the basement. The first card assigned to me on Trello titled Basement: UK previous editions represented an audit of these titles: determine what to keep on-site, what to move off-site, and what to discard/donate. Agile provided a framework for undertaking this daunting task through the scrum methodology, continuous feedback and allowance for experimentation and being adaptable.

Our basement, like many others, was a collection of everything we had ever purchased/owned; items were retained in some instances simply because we could and just in case. Nearly 650 metres of UK material needed shifting from the basement. The Scrum project management framework, part of the Agile methodology, promotes a self-managing approach to tasks worked in short sprints.Footnote 6 During the first scrum sprint, I was conservative with the selection of material to retain on-site, and used our main first floor collection of UK materials to guide my initial decisions. The first floor is comprised of heavily consulted textbooks, loose-leafs and core practitioner books, collected against our collection development policy: “the Library collects legal texts in certain specialist subject areas such as banking, commercial law and arbitration, competition, employment, insurance, professional negligence and shipping, amongst others. We are also the specialist library for ecclesiastical law. In addition, we offer access to a full range of legal resources for EU and American Law”.Footnote 7

My preliminary approach was to record the number of superseded volumes for these titles currently located on the 1st floor of the library, which resulted in 177 metres of materials making the first cut of books for on-site retention. I opted to keep the previous editions of core textbooks, such as Civil Procedure, including its run under former titles, The Supreme Court Practice, and the Annual Practice. I also chose titles such as Scrutton on Charterparties and Bills of Lading, which deals with maritime contracts and its superseded volumes dating back to 1886, in an effort to reflect our collection development policy. The Agile method is iterative and collaborative and after sharing this initial list with the Librarian, I was encouraged to retain more material on-site. Individual titles were also highlighted as imperative for our core collection.

Timothy Berichon, director of CAE Services and Insights and Intelligence at The Institute of Internal Auditors, noted that when the Agile method was applied to financial audits, breaking down tasks into smaller pieces allowed auditors the flexibility to learn more as the pieces of the project progress naturally: “they become more collaborative with internal stakeholders as collective uncertainty diminishes and a clearer sense of conclusion against work objectives or hypotheses is reached.”Footnote 8 Catch-up meetings with the team were scheduled to review our progress. These meetings provided an indication of how the audit of the UK collection fit within the restructure of the library, which was beneficial due to my inexperience of working with legal materials. For instance, our gallery space was reserved in the reorganisation for previous editions and legislative material, signifying the importance of superseded material being accessible for our members’ research needs and demonstrating the need to try to retain more of the basement materials on-site. I could also follow the progress and evaluation procedures for other specialist subjects in our library on the Trello boards, such as the collections for the American and EU jurisdictions, handled by other colleagues.

The visual dashboard of Trello provided an opportunity to collaborate and communicate regarding specific book series during the process. For instance, an amendment was added to a Trello card to identify titles that could be discarded from the UK basement collection; the example of tax series was suggested. Following, I discarded previous editions of tax materials, such as Tolley's Inheritance Tax because they did not fit in with our collection development policy, were available online, and collected by another institution. Berichon explains communicating on an open web-based service such as Trello allows you to track observations; this visual type of communication is easier to follow and creates an account of the process behind the project, as opposed to the just the issuing of a final product or report.Footnote 9

Prior to my employment, the UK basement material was classified according to the MOYS classification scheme, which allowed me to more easily identify titles from our specialisms to keep in the next sprint. The second review focused on our library's specialisms, such as ecclesiastical law and employment law. Henry Miller's A Guide to Ecclesiastical Law for Churchwardens and Parishioners and A.R. Thornhill's Employee Trusts and Approved Employee Share Schemes were added to the core collection of previous editions identified in the first sprint. An approximate 290 metres of material from the basement would now remain on-site.

MOVING ITEMS

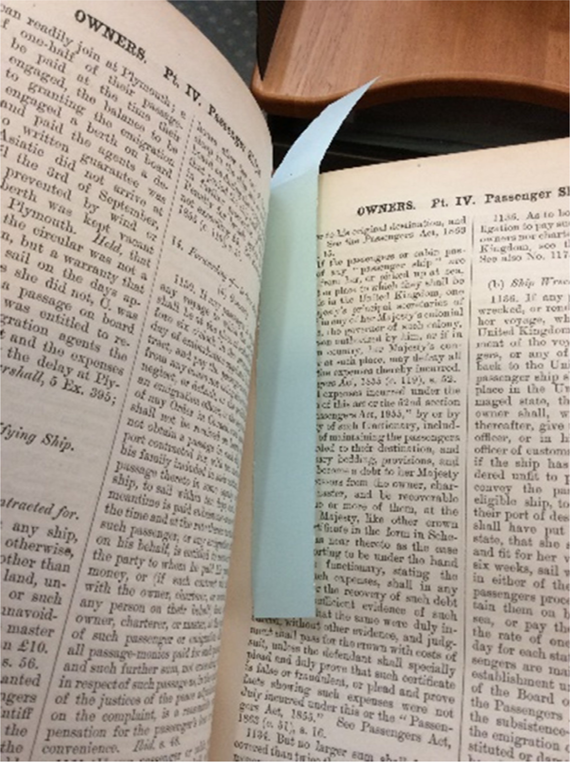

The process of relocating items from the basement to the gallery and off-site was handled by temporary staff and a contracted company respectively. The Agile method provides flexibility for experimentation and in an effort to reduce confusion for those unfamiliar with the way our resources are organised, an idea developed to use a colour-coded system with strips of paper placed inside the books. This would allow for quick identification of the texts that should remain for the gallery and those moving to an off-site storage facility: orange meant off-site and blue indicated the gallery. Distinguishing between the two categories of books by colour also extended to Excel spreadsheets, allowing for easier statistical analysis and record checking.

Figure 2: Using the Agile method.

Temporary staff placed these tags within the books (regrettably, we did not used acid-free paper), so when the external company came to remove items they would know which to take. It was a gross underestimate on my part for how long it would take to tag the books. Handling that many volumes lasted about two weeks and took three individuals to complete.

Temporary staff were responsible for the physical move of the blue-tagged materials to our upstairs gallery. During the move, some items were missed; books meant for retention were not collected, due to oversight of the colour tag, or the book not being properly tagged in the first place. Distinct titles could share the same call number as another, leading to a mix-up of how to code items. However, the Agile method encourages continued review and evaluation of the project; this error led to the addition of cards on Trello for a post-project assessment, such as review of catalogue records. Even after the initial bulk move of titles to the gallery, I continued adding to the on-site collection, reviewing the member queries we received through email and phone to make decisions.

Figure 3: Tags in the books.

Input from my co-workers also contributed to more titles retained throughout the process.

CONCLUSION

In September 2020, the physical move of materials for the Basement Project was complete, with thousands of volumes relocated. Although our primary goal of the project was finished, as a team we continue to finesse elements of the Basement Project, with Agile still serving as a project management framework for our post-removal tasks. We record updates on Trello and follow the iterative process for reviewing decisions. For example, after seeing the reorganised library space following the book move, our preliminary assessments of materials were re-examined. We created a spreadsheet for the purposes of recording volumes to transfer from off-site storage to the library on-site. We continue to add to the narrative and transparency of our decision-making process for the Basement Project.

I believe the greatest strength of the Agile project managing is its ability to accommodate. It accommodated changes to staff working patterns during a worldwide pandemic and allowed external departments and contractors to easily jump in and contribute to the project at various points. It also accommodated modifications to the library layout and retention of resources as we reviewed our collection through Trello and collaborative spreadsheets. When the University of Colorado Boulder adopted Scrum to manage their digital initiatives, they found the technique promoted, “adaptability so the team could address the inevitable changes that occur over the life of a project.”Footnote 10 I believe we found the same success with adopting this type of project management solution for our book move.