Introduction

The voyage we are now about to describe established no new ‘farthest north’, but we are including it in our Polar chronology because it is unique in the annals of Arctic exploration, and will add variety to a narrative that may have already become slightly monotonous through its repetitious accounts of travel by ship and sledge. The leader of this expedition proposed to abandon recognized modes of travel and make an attempt to reach the Pole by air. This method, which seems quite natural to us today. . .was considered fifty years ago as something fantastic, a page out of Jules Verne (Crouse Reference Crouse1947: 239).

Until 2000, when the English adventurer David Hempleman-Adams dared to repeat Salomon August Andrée's attempt to reach the North Pole by balloon, it was often assumed that polar ballooning both began, and disastrously finished, with Andrée's fateful flight in 1897. This is not the case. Polar ballooning has a more colourful history than this, full of optimistic proposals and a host of eccentric characters. Perhaps the most appealing character of all, not least, as his story is almost wholly forgotten, was a retired naval commander and journeyman lecturer who became fascinated by the entertaining possibilities of flight. But who was he, and what was he proposing, and why did it encourage such public debate, even drawing the attention of satirists and songsters alike to ‘protest against these preparations for a costly performance of Balloonacy in the theatre of everlasting ice and eternal snow’? (Punch 24 January 1880).

Whilst some narratives of Arctic exploration history overlook aviation, most entirely neglect the proposals for early Arctic ballooning. If mention is made, then attention naturally falls on Andrée's attempt. Crouse's account of Andrée's balloon voyage provides the above quotation: a comment that could also be reasonably applied to Commander Cheyne's balloon proposals. One can be excused for thinking, as many at the time did, that Cheyne's plans leapt straight from the pages of a Verne novel, or from the latest juvenile adventure story. There are certainly similarities: a bold plan presented by a man with brave credentials; implausible machinery sustained by an ideal of progress; an elusive goal (Freedman Reference Freedman1965). And like Verne's novels, public imaginations were seized by Cheyne's proposals, and so it is even more remarkable that no attention has, thus far, been paid to his story.

When asked about Cheyne in 1930, Vilhjalmur Stefansson, a polar historian of some authority, confessed his ignorance: it ‘indeed took down my pride for I have long been a collector of polar books’, and ‘have a library of several thousand volumes’. After many months of research Stefansson was glad to announce that he had learnt a little more about the commander. His ‘plans were so ill assorted, in addition to being ahead of his time, that his detractors succeeded in placing him where he has been remembered, insofar as he was remembered at all, as a charlatan’. ‘Cheyne may not have been sound’, he concluded, ‘but he was provocative, active, and early. He therefore has a place in the history of the application of aeronautics to geographic discovery’ (Stefansson Reference Stefansson1935: 97–98). Prompted by Stefansson's appeal, Carolyn P. Ward prepared a brief account of early ballooning, affirming the historical importance of Cheyne's campaign. It was hoped that there would be enough material for a publication on the subject, but the archival trail went cold (Ward Reference Ward1935). Since Ward's account, published over seventy years ago, nothing new has been added to our understanding of these remarkable proposals. Despite languishing in obscurity, there is much to commend an analysis of Cheyne's struggles to launch an expedition by balloon: the first chapter in the history of manned polar aviation.

The popular profile of ballooning as a capricious and ‘unscientific’ business has a long history. From the very first ascents in the late–eighteenth century, ballooning was identified with risk and showmanship, a spectacle both of the fashionable pleasure garden and of the unruly common crowd, and it never lost an association with entertainment and fantasy (Tucker Reference Tucker1996; Gillespie Reference Gillespie1984; Stafford Reference Stafford1983; Rolt Reference Rolt1966; Hodgson Reference Hodgson1924; Alexander Reference Alexander1902). For the many who commentated on the continuing ‘balloon craze’ in England during the late Victorian period, the balloon remained a symbol not just of discovery, innovation, and travel, but also of recklessness, decadence, and moral impropriety. Cheyne's struggle for credibility as an explorer with an innovative ballooning plan can be read within this general context of public scepticism.

It is equally important to remember that public attitudes toward exploration varied dramatically. After the British Arctic expedition under Nares had returned so soon from the north in 1876, many quickly turned against the project of exploration. The question increasingly asked was not ‘why explore’ but rather ‘at what cost’? The mixed reactions to Cheyne's proposals allow us to reconstruct a profile of public feelings toward exploration; of a continuing debate in which individuals like Cheyne had to campaign vigorously not only for their chosen technique of travel, but also to justify the continuation of polar exploration itself.

Reconstructing the life of a showman–explorer

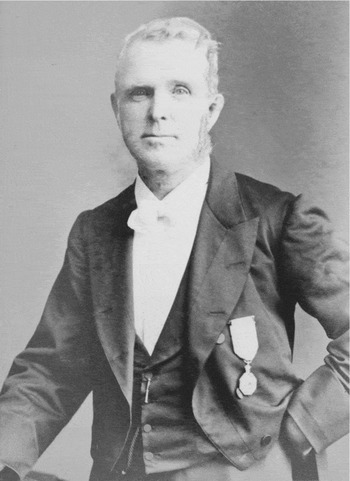

The Commander, although over fifty years of age and with whitened hair, yet looks and is strong and hardy and possesses much more vigor than many men ten or fifteen years his junior. He is a little below the medium height, but with a well knit frame, complexion ruddy, penetrating eyes of gray, and wears small white whiskers (The New York Herald 18 November 1881).

With the Arctic Medal pinned to his dinner jacket, Cheyne was proud to advertise his polar credentials. A veteran of three Franklin search expeditions, and a naval career in which he saw service in hydrographical survey and convoy during the Indian Mutiny, Cheyne certainly cut a dashing figure, as he eked out retirement in crowded lecture halls across the country. Before expanding more fully on the details of his vision for a grand balloon campaign, it is useful to attempt to reconstruct an account of his life. With few family records surviving, or much that can be found in the archival record, it is unsurprising that there has been no previous biographical treatment. Yet there is much in his story of value to the polar historian for it provides a colourful entry point into the ‘show–business’ of exploration during this period: an account of vigorous debates and lobbying over the future of exploration, of appealing exhibitions and displays circulating enduring images of the northern space, and, not least, of the tribulations of life for the first Arctic explorer to turn professional lecturer.

John Powles Cheyne (Fig. 1) was born in 1826 in Islington, London. He was the second son of Captain George Cheyne, R.N., a Scot who was an old friend of Sir William Edward Parry. John's first voyage was in the brig Chedabucto en route to New Brunswick. The vessel first went to Cuba and New Orleans, and thence to Halifax and was nearly lost in a hurricane off Cape Hatteras in 1842. Shortly afterward, whilst living in Halifax with his father, he was appointed Master's Assistant to the naval steam brig Columbia, which was engaged for four years in surveying the Bay of Fundy. In January 1848, at the age of 21, Cheyne secured his first appointment as a midshipman, on James Clark Ross's Franklin search expedition, and he would later serve on two other Arctic voyages. In 1855, and shortly after his final return from the north, he married Emma Gardner, a young lady from Highgate. Soon after she gave birth to their first son, appropriately named John Franklin Cheyne. After John Franklin, there followed three daughters, Mirabelle, Kate and Beatrice, and in 1862, a second son, the prodigiously named Edward Parry Leopold McClintock Cheyne. The boy's father was evidently proud of his Arctic connections.

Fig. 1 Commander John P. Cheyne, the showman-explorer, recently discovered photograph, c. 1876. Courtesy private collection.

In 1860 the young family took rooms in an Islington terrace, but by 1871 it was living in more comfortable circumstances at Prurose Villa, near the village of Crookham in Hampshire. Within a few years the Cheyne troupe had moved back to London, first living in Addison Gardens, before moving nearby to 1 Westgate Terrace, just off the Old Brompton Road. Maintaining a large household on a small naval pension, supplemented by some earnings from his limelight lectures, must have been difficult for Cheyne. Away for long periods, lecturing across the country and overseas, and with family finances strained, it was not to be a home filled with constant happiness. The very public failure of his grand expedition proposals, no doubt, added to the pressures on his marriage, and sometime after 1885, the couple separated. Emma stayed in London, making a home for herself at 24 Barons Court Road, supported by the earnings of her daughters.

At this point Cheyne probably migrated to North America, but details are scarce. It is certain he lived in Hamilton, Ontario during the 1890s, and records survive that suggest he was still lecturing. However, the documentary record runs out in these later years, and it is hard to track him down. On 1 April 1894 he was awarded another pension, receiving £75 a year, which must have improved his circumstances. It appears that he later travelled east, moving to Nova Scotia and taking a house in the prosperous naval town of Halifax. Cheyne lived alone at 118 Robie Street, just up the hill from the Royal Yacht Squadron, in a house with a view across the large natural harbour. He died of hepatitis, at the age of 75, on 8 February 1902, and is buried in Fort Massey Cemetery.

Arctic experience

Leaving Cheyne at rest in the country he grew to love, it is fitting that our story now begins, for it was to Canada that Cheyne would journey on his first major voyage. In 1848 he was appointed to Enterprise, under James Clark Ross, on the first of many expeditions to push north into the Arctic in search of the missing Franklin party. He was the only midshipman on the voyage. Departing London in May, Ross's ships made a frustrating passage north hampered by heavy ice, and, having entered Lancaster Sound late in August, were forced to winter at Port Leopold, at the northeast tip of North Somerset. The following spring, sledging parties managed to fight their way south to Fury Beach, down Peel Sound, and along the unexplored west coast of North Somerset; forays on which a young Lieutenant McClintock would get his first taste of the rigours of Arctic travel. It proved impossible to spend a second season in the Arctic, since the ships were beset in the ice and were only released in September 1849 near Baffin Bay (Ross Reference Ross1994; Jones Reference Jones1971; Cyriax Reference Cyriax1942).

The expedition failed to find any trace of Franklin and his men, but the public enthusiastically welcomed their safe return. The Ross expedition was to be the first act of a prolonged drama of hope, perseverance, suffering, and loss, as numerous search expeditions were sent to the north. The sublime dangers of the Arctic space, and the individual heroics of a succession of ‘gallant’ naval officers, were played out before an eager public, in the newspapers, on stage, and in gripping published narratives. As Cheyne returned to his lodgings at the Royal Hospital in Greenwich late in November, London society thrilled at a number of Arctic spectacles mounted by enterprising showmen for the Christmas holiday season. At Leicester Square, Robert Burford exhibited another lavish polar panorama, basing his representation of summer and winter scenes on the original watercolours of W.H.J. Browne. Gompertz's Polar Regions panorama was shown at the Partheneum Assembly Rooms in St Martin's Lane, before touring the provinces. Danson's View of the Polar Regions was running a brisk trade at the Colosseum, whilst dissolving–views were being shown in rooms all over town, including the Royal Polytechnic Institution and the hall of the Western Literary Institution, just off Leicester Square. It is probable that Cheyne ventured into London to enjoy some of these shows. The return of the Ross expedition made clear that exploration was a performance which lent itself to spectacular representation, a performance relying as much on imagined success, as it did on real achievements, and many years later, Cheyne would utilise similar techniques in demonstrating the value of constructing, and promoting, appealing images of the polar regions.

Having returned from the Arctic, Cheyne was first appointed to a frigate, but before taking up his post he was ordered to Resolute under Horatio Austin. There are just a few pieces of mixed information that one can draw together to describe the record of his involvement as a mate on Resolute during its voyage of 1850–1851. In the first ‘fancy dress ball’, for example, held on Resolute on 5 December 1850, amongst an eclectic hodgepodge of colourful costumes, Bedouin Arabs, Roman centurions, battle of the Nile veterans, Greenwich Pensioners, pirates and smugglers, we learn that Cheyne attended as ‘Miss Maria’, drawing much compliment (Osborn Reference Osborn1852: 170–171). He donned a dress again for the ‘Royal Arctic Theatre’ on 9 January 1851 aboard Assistance, playing ‘Distaffina’ in the ‘Grand Farcical Tragical Melo-dramatical Serio-Comic’ Bombastes Furioso, to much plaudit. It is interesting, as a future travelling showman, that among what little we can discover of Cheyne's early naval career, are a few passing mentions of his skills in accounts of the ship's amateur theatricals. In later years he actively promoted an image of himself as long-serving Arctic ‘veteran’ as a means to attract a paying audience for his lectures, whilst trying to cultivate his aeronautical credibility. His experience of sledge travel, Cheyne would later claim, had given him adequate insight into its advantages, and considerable limitations; his role in scattering silk messages amongst the ice had ‘sharpened’ his understanding of predicting wind patterns, and of the finer technicalities of balloon construction. One may suggest that his time aboard ship in the Arctic, if anything, had introduced him to the particular joys of theatrical performance and given rise to a lasting love of the stage.

Cheyne no doubt contributed to the daily running of the ship, as did many other junior officers on the numerous search expeditions during this period, but his was a role that rarely warranted any sort of undue attention. The theatre of exploration depended upon its lead characters, heroic, prominent, with defined obligations and duties, and clearly pronounced achievements. The story of the Resolute expedition therefore was reported through the dispatches of its senior officers, and through the accounts of the following spring's sledging campaign, not through the details of the daily chores of running a ship on service. That said, not every day was mere routine. Before the blanket of winter fell on the ships, beset in ice to the northwest of Griffith's Island, rockets, balloons (Fig. 2), captured foxes, and carrier pigeons were all employed in a vain effort to spread word to any of Franklin's missing crews still alive.

Fig. 2 ‘Dispatches leaving HMS Assistance by balloon’, watercolour after a sketch by Clements Markham. Courtesy Scott Polar Research Institute.

Sherard Osborn, officer in command of the screw steam ship Pioneer, the first to operate in the Arctic, was given charge of organising balloon operations. Medical officers on each ship were also ordered to assist in preparing the chemical agents for producing hydrogen, and in maintaining the apparatus, a contraption of barrel, siphon and gas purifier. Osborn had been ordered to investigate a variety of paper messenger balloons prior to the departure of the expedition early in 1850. One manufacturer, Charles Green, had perfected his messenger balloons after many years as an aeronautical showman: he used them for scattering advertisements on the locals in towns at which he was due to perform ascents in his large balloon. Osborn invited Green, a Mr Derby, and George Shepherd, another well-known balloon supplier, to test their messenger balloons by flying them from the roof of the Admiralty. Shepherd's large balloon eventually arrived in Brighton (some 100 km away) and was deemed sufficiently successful to convince the Admiralty to order a batch (The Times 19 March 1850). In the Arctic, Shepherd's balloons were used as soon as Austin's ships had the chance to deploy them. Messages dispatched from Assistance that October were later picked up by sledge crews on the opposite side of Wellington Channel, north of Port Innis. ‘Neither this or the non-discovery of papers by travelling parties in 1851’, Osborn wrote later in his expedition journal, ‘can offer proof against their possible utility and success; and the balloons may still be considered a most useful auxiliary’ (Osborn Reference Osborn1852: 174).

The following spring there began a more conventional campaign of searches by man-hauled sledge: parties were dispatched to the north and south, in the process charting large extents of unexplored coastline. Cheyne took charge of one of three supporting sledges in McClintock's Melville Island division. Accompanied by seven men, with a sledge he christened Parry, he acted as fatigue party drawing McClintock's sledge for the first days of travel. Cheyne's team were twelve days away from ship and marched nearly 200 km. During this spring programme McClintock's main party covered an impressive 1,425 km, charting the entrance to McDougall Sound, resurveying the south coasts of Byam Martin and Melville Islands, but returning with no traces of the missing Franklin crews. The ships were released from the ice on 8 August and shortly thereafter sailed for home. Cheyne was promoted to Lieutenant on 11 October 1851, after the expedition's safe return, and for the third time was assigned to a ship preparing to search for the missing Franklin expedition.

He joined Assistance at anchor in the Thames, shortly before the ships of a squadron commanded by Sir Edward Belcher sailed on 15 April 1852. Arriving off Beechey Island on 13 August, Belcher proceeded with service parties, under the commands of Richards and Cheyne, to examine the island and its adjacent coasts once more. Cheyne was instructed to ascend to the summit of Beechey Island to search the cairn left by Franklin's crew, but again no traces were found. Taking Assistance and Pioneer further up Wellington Channel, Belcher discovered Northumberland Sound, off Grinnell Peninsula on northwest Devon Island, and put his ships into winter quarters. The first message balloons were dispatched from Resolute on the clear morning of 12 September, and the ship's Master George McDougall gives a short account of this (McDougall Reference McDougall1857: 127). Having been loaned a number of electrometers from Kew, Cheyne was excused from shipboard duties and directed to attend to a series of scientific observations. Again, it actually proves far easier to find details of Cheyne's roles on stage, than of his official duties on ship. On the evening of 9 November 1852, for example, in a programme of theatricals got up to celebrate the birthday of the Prince of Wales, Cheyne again found himself dressed in a frock entertaining an eager audience. The young lieutenant was lead player in the corps dramatique of ‘The Queen's Arctic Theatre’, playing the part of ‘Rosa’ (‘an electrifying Aurora from Sadler's Wells’) in the Irish Tutor (Belcher Reference Belcher1855: 152–153).

The following spring, as sledge parties searched the surrounding regions for traces of the Franklin expedition, Cheyne remained with Assistance, tinkering with his instruments, shooting bears, and taking charge of the balloon apparatus. On clear days with brisk southerly winds during June, with the ships still locked in their winter quarters, silk messages were once again sent aloft in Shepherd's small hydrogen filled balloons. On 14 July, as the last of the sledge parties returned to the ships, Belcher began to move Assistance and Pioneer south toward Lancaster Sound. The ships were caught in the ice in Wellington Channel and forced to winter to the north of Cape Osborn, Devon Island. During October 1853, Cheyne was ordered to North Star, which had remained at Beechey Island as a base for the squadron, to attend to tidal and meteorological observations under Commander W.J.S. Pullen. It was not to be his only visit: the ships were released from the grip of ice in August the following year but, still unable to make passage through to Lancaster Sound, they were abandoned. It had been a difficult season for Belcher's squadron. He had already ordered Resolute and Intrepid to be abandoned in Barrow Strait, and so the officers and crews of all four ships assembled on the last remaining ship in the squadron, North Star, at Beechey Island. Relieved by supply ships on 26 August 1854, the crews limped home to face a mixture of public praise and official criticism. Though Belcher was later acquitted at court-martial over the loss of four ships, his very dramatic failure effectively prevented any further Admiralty search expeditions.

The Franklin search reached its conclusion in 1859 with McClintock's return from King William Island, aboard Fox, financed by Lady Franklin herself, bringing relics sufficient to prove the fate of the missing crews. Seizing on a chance of supplementing his meagre half-pay, Cheyne approached McClintock, a former shipmate, requesting permission to publish images of the relics, which were then on display in the museum of the United Service Institution. McClintock happily gave his endorsement, appearing himself in a bold pose as returning hero. A set of these stereoviews, with a descriptive catalogue, commanded the price of one guinea; evidently, the image of the explorer could turn a handy profit. Cheyne sold sets direct from his London home to an eager public.

Cheyne spent much of his time after his Arctic service ashore, and with only intermittent postings thereafter it is no surprise that he looked to turn his experiences to some sort of financial advantage. In 1873, we find Cheyne, a patriotic officer struggling on half–pay in London, attending evening meetings of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS). On 3 November, for example, the secretary of the society, Clements Markham delivered a paper on the failures of C.F. Hall's Polaris expedition, and the successes of his cousin Albert's cruise in the steamer Arctic. In the discussion that followed, Cheyne offered his support for future exploration: ‘it was his deliberate opinion that it would be a comparatively easy thing for an expedition to reach the North Pole’, one report noted. At the same time, he urged the RGS to continue promoting Arctic research ‘until the North Pole was finally reached’, warning that ‘if England did not now do her duty in this respect, she would find other nations surpassing her’ (Markham Reference Markham1873: 18–21). It is at this moment, with London beginning to buzz with the news of a new polar expedition, that Cheyne started to voice his own Arctic interests.

Cheyne delivered his first public lecture in a crowded London concert hall on 13 November 1875, but it was to be no glittering debut. For many months he had been working hard on his manuscript, jotting together notes and reminiscences, dipping into popular histories of exploration, and gathering illustrations, and he had even managed to attract the approval of G. Ward Hunt, the First Lord of the Admiralty, who was happy to advertise his support for the evening's entertainment. The curtains were pulled back, an expectant hush descended on the audience, but as the lights dimmed poor Cheyne muffed his lines. Perhaps he was trying to be too straight-laced and scientific for this first lecture, rather than using his obvious ‘vaudeville’ skills to entrance the audience. ‘The attractiveness of the subject. . .drew together a considerable audience, but the result fell short’ (The Times 15 November 1875). Even in spite of these problems the lecture was ‘not altogether unsuccessful’, The Times conceded, and when Cheyne offered his services to the Admiralty for future Arctic expeditions, at the close of the lecture, he was given hearty applause. Some, no doubt, felt that he would do better to stick to exploration than embarking on this new career in the limelight.

Whilst Cheyne may have been unable to satisfy a discerning London audience at this early stage, he soon proved to be a success in the provinces. On 19 January 1876, for example, he delivered a brisk summary on the state of exploration before a full audience at the Plymouth Mechanics Institute, and was booked again for the following night. Meanwhile, the newly-edited script of his ‘Arctic Regions’ lecture had been published by Frederick York, a reputable magic lantern manufacturer, accompanied by an attractive set of fifty of the dissolving views. In village halls and drawing rooms across the country, audiences could explore the mysteries of the Arctic with ‘brave Commander Cheyne’, and the reading proved immensely popular. On 18 November he lectured at Tunbridge Wells, soon after hearing of the return of Nares’ ships, reaffirming his belief that the North Pole remained ‘practicable’, and offering a tentative solution. ‘As a forlorn hope. . .if it came to the worst’, he suggested, he would ‘be prepared to proceed to the farthest point north by a vessel, and then by ballooning would probably be able to surmount the ice difficulties’ (The Scotsman 20 November 1876). Perhaps he was not yet sure in his mind of the feasibility of the plan, but before long Cheyne's suggestions had taken a flight of their own.

Lectures and lobbying: a long campaign revisited

There is always a good deal to be said in favour of Arctic exploration. It has been said over and over again, sometimes to willing, at others to reluctant ears, but it will doubtless continue to be said until the great mystery of the Pole has been revealed. We may acknowledge at once that adventure is a good thing, that the advancement of knowledge is a good thing, that the employment of British seamen in deeds of endurance and enterprise is a good thing, that the history of the English Navy, and even the English nation itself, would not be what it is without the great Arctic tradition of heroism and daring, and yet we may fairly hesitate when we are asked to give encouragement and countenance to a new scheme for the exploration of the Pole. We know too well, from repeated and too often mournful experience, what the perils of Arctic exploration are (The Times 8 January 1880).

The idea of reaching the North Pole by balloon was evidently a dramatic one, and the public thrilled at the thought. This section follows Cheyne as he begins his career as an Arctic showman. He travelled back to London, and, on 29 November 1876, delivered his new lecture before a crowded hall at the Birkbeck Institution. London was full of talk about the return of Nares’ ships; a dispute was also ‘raging’ in the press on the nature of a future route to the pole, with the news that the Americans were petitioning Congress for an expedition to leave the following year. Cheyne ‘rejoiced’ to hear of this ‘because he knew England would not be outstripped by another country on the question of Arctic exploration’ (The Scotsman 30 November 1876). On 9 February 1877, he was in Edinburgh lecturing at the George Street Music Hall, the fashionable assembly room where Dickens had given public readings, performing under Ward Hunt's patronage and with the advertised support of Gathorne Hardy, the Secretary of State for War (The Scotsman 3 February 1877). With illustrious supporters, his working budget had improved and he was able to add new slides, musical accompaniment, and ‘a New Dissolving View Apparatus’, powered by ‘oxy-hydrogen lime-light’, that projected ‘brilliant’, and reliable, images, 25 feet (approximately 4m) across, throughout the course of his performance. His new ‘Voyage to the North Pole’ lecture, a polished version of his old script which retained its familiar pro-Navy rhetoric, was ‘exceedingly well received’, and Cheyne used the platform to announce formally that he was organising a new expedition.

Growing in confidence as a lecturer, and having significantly improved his performance, Cheyne was beginning to attract a degree of notoriety. He soon secured a regular engagement at the Alexandra Palace, a popular site of recreation that had just opened in north London. Cheyne delivered his lecture twice on the day of the ‘Great Popular Fete’ held in celebration of Queen Victoria's birthday, amid a lively mix of military bands and circus performers, and he continued to lecture throughout the summer (The Times 2 June 1877). Bound by these metropolitan engagements, and a lecture series booking in Salisbury, he was unable to travel to Plymouth for the annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science late in August, at which a paper on polar discovery by means of balloons was read on his behalf. It was a meeting with a distinctly polar feel. The Arctic veteran Admiral Sir Erasmus Ommanney delivered a detailed address as president of the geography section, evaluating the record of the Nares expedition and suggesting future areas for exploration and scientific enquiry. Choosing to withhold any direct comment on the nature of Cheyne's novel proposals, Ommanney's verdict was, nevertheless, remarkably clear: ‘instead of nations racing for the Pole’, he suggested, ‘let us accomplish what is practicable’ (Anon. 1878).

Though official support had not been forthcoming in Plymouth, a short while later, on 20 September 1877, Cheyne delivered a lecture that was to prove of great value to his polar ambitions. Given the stage in the Royal Aquarium, Westminster, for three consecutive nights, Cheyne described his plans with new conviction, ‘not merely for the purpose of interesting the public, but in order to show that the British people should set on foot another enterprise to solve the mystery of the great unknown region’ (The Times 21 September 1877). He announced that he had already succeeded ‘in enlisting sympathy for his project’ among 22 local committees, formed to promote the proposal and help collect the sum of £23,000 which he had calculated would be required. Tracing his finger suggestively across an illuminated map of the Arctic, he appealed to the meeting for their help. Rising from the body of the audience, Henry Coxwell, the most distinguished English aeronaut of the period, offered his support, confirming that it would be possible to devise balloons for the purpose; the only requisites being ‘skill, judgement, and money’. With such a public display of confidence in his idea, and now finding his feet as a performer, Cheyne theatrically asked his audience to shout out whether he should proceed with the scheme: the rousing vote was overwhelmingly ‘affirmative’. Now where to find the skill, judgement, and most importantly, the money?

The following week, the first published images of his vision for polar flight were presented to an expectant public. ‘All attempts made by various nations to reach the North Pole have, up to the present time, resulted in failure’, announced The Graphic, ‘but a novel plan has been suggested by Commander Cheyne, R.N., which appears to afford some hope that the idea for which so much money has been spent, and so many hardships endured, may ere long be un fait accompli’ (The Graphic 6 October 1877). Despite confident performances in his London lectures, The Graphic noted, he had ‘yet to receive encouragement from either the Government or the nation’. This was, perhaps, no surprise when one glanced across the page to admire Cheyne's new technique of polar travel (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 ‘The proposed polar expedition – how to reach the pole by balloons’, from The Graphic, 1877. Author's collection.

Although Coxwell had offered to help in drawing up the plans, the image was not one to inspire a great deal of confidence. Three large balloons were to be held by rigid spars in a triangular formation, carrying six men, three tons of gear, stores, provisions, tents and sledges, a supply of compressed gas, and a team of dogs. The spars were to be fitted with foot-ropes so that the men could scramble from one balloon to another ‘in the same manner as sailors lie upon the yards of a ship, and the balloons would be equipoised by means of bags of ballast suspended from this framework, and hauled to the required positions by ropes’. The boat cars were to be housed in for warmth and kept in touch with the ship by means of a telegraph wire paid out from a huge wheel as the balloons moved northward. In addition to ensuring constant ‘telegraphic communication’, the wire would also record the distance traversed, being marked every 5 miles (8 km). To aid the navigation of this floating formation, trail ropes were to be used to prevent ascent above a certain height, about 500 feet (152 m), at ‘which elevation they would be balanced in the air, the spare ends dragging over the ice’.

The Graphic continued by describing Cheyne's timetable of attack: the balloons were to start at the end of May, on the curve of a predetermined ‘wind circle’. The nature of this wind pattern was to be forecast, to Cheyne's great confidence, through a series of shipboard measurements, and at two meteorological observatories some 30 miles (48 km) distant in opposite directions. With knowledge of the diameter of this wind circle, and the known distance to the pole, Cheyne estimated that the balloons could be landed within ‘at least twenty miles of the long-wished-for goal’. Having moored the balloons, Cheyne's band would make their final assault on the pole, plant a flag, and when the necessary observations had been carried out, secure a favourable wind blowing to the south. Having reached the latitude of the ship, the ‘returning voyagers’ would follow it performing the remainder of the journey, if necessary, ‘by means of the dogs and sledges conveyed in the balloons’. The Graphic's only commentary on Cheyne's proposals were that they afforded ‘some hope’; a flattering verdict at this stage, considering its wild optimism. Though the image was certainly appealing, brimming with the rough-and-ready reasoning of an adventure story, many people would need more information before they could be convinced.

But the swirl of engagements continued. On 24 October, Cheyne lectured in the Langham Hall, Great Portland Street, before the Turkish Ambassador and Viscount Pollington, and in the following week was the star attraction of a gala benefit held at the Cannon Street Hotel. With a number of important guests attending, including George Gleig, late Chaplain General of the Forces, and the Lord Mayor of London, Thomas Scambler Owden, the ballroom was filled with limelight views and some rousing songs performed by Vernon Rigby, a favourite at the Alexandra Palace (The Times 25 October 1877). Shortly afterward Cheyne joined the ‘Lecturer's Association’, a group of like-minded popular performers who organised their own bookings, and throughout 1878 he travelled across the country to spread his message. It is possible to follow Cheyne some way on his path as his performances were often noticed in local newspapers for that year. The Southport Visitor, for example, declared that Cheyne's views were the ‘best that they had ever seen’. The Cambridge Chronicle agreed that Cheyne's lecture ‘was one of the most interesting we have ever listened to’. The St Helens Standard reported that ‘tales of his experiences amongst the icebergs were thrilling and exciting to an intense degree’. The Hull Express testified to the ‘long and continued applause’, whilst The Staffordshire Advertiser described that ‘he riveted the attention of the audience and entirely carried their sympathies with his absorbing narrative’.

Cheyne also proved an attraction in Scotland spending much of 1878 lecturing there. In Edinburgh he was ‘exceedingly well received’; in Dundee his ‘graphic descriptions of wild scenes’ were ‘intensely interesting’; in Crieff his performance was ‘most interesting, dynamic and vivid’ and so too in Aberdeen: ‘Views of Arctic scenery are brought out with most telling effect, storms amongst tumbling masses of icebergs, ships in danger or crushed wrecks, the frozen north where repose the remains of those brave seamen who perished with the last Franklin Expedition, are all alike beautifully and vividly described’. Cheyne opened the winter session of the Airdrie Mechanic's Institute with a lecture entitled ‘Five Years in the Arctic Regions’, and was ‘warmly applauded’ (The Scotsman 13 November 1878). On 2 December he performed in a crowded city hall in Glasgow and, after a show of hands, yet another local committee was added to assist him with gathering funds (The Times 3 December 1878).

By January 1879, after this intense lecture campaign, Cheyne had managed to form a total of 35 local committees, ‘headed in most cases by the provost or other public authority’. At this point the details of the plan were still broadly the same as they had been when The Graphic raised the public profile of the scheme in 1877: a triangle of three hydrogen filled balloons carrying boat-cars, men and sledges bound for the pole on a predicted wind track. Cheyne had also made some appealing additions, suggesting that he might continue over the pole to attempt a crossing of the polar ocean, whilst his ship performed a multi-year scientific survey, before moving north to affect a circumnavigation of Greenland; optimistically offering a mix of adventure, bold discovery and scientific observation to elicit more support for his plans. By the end of June there were 49 local committees, and a London gathering was planned. On 3 July, at Willis's Large Rooms off St James's Square, Cheyne gave the most important lecture of his career thus far. With John Puleston M.P. in the chair, he duly delivered his popular lecture, surrounded by a number of influential supporters, inaugurating the ‘London Central Arctic Committee’, a formal body to lobby government for financial support (The Times 3 July 1879). The group held its first meeting at the House of Commons on 7 August, drawing up action plans for the local committees, securing the use of rooms at the Royal Society of Literature, and arranging the opening of an account at the Bank of England. The ‘British Arctic Exploration Fund’ was officially opened to public subscriptions the following morning (The Times 9 August 1879).

With high hopes, Cheyne moved north to Sheffield later that month to attend the annual meeting of the British Association, but his plan soon came under attack. Although the geography section meetings that year were to be dominated by the exploration of central Africa, and reports from the continuing Afghan War, with Clements Markham in the chair as president it is not surprising that the polar regions were a subject of much debate. On the 26 August, Commander Lewis Beaumont, whose sledging heroics on the Nares expedition had earned him promotion, read a paper on Arctic research, and delivered a critical commentary on Cheyne's plans: ‘the future of Arctic work must depend upon the persevering efforts and reasonable arguments of those who advocate it. . .the revival of interest in Arctic exploration will commence amongst those who are sure to be more influenced by valuable and substantial results as an object, than by the prospect of a brilliant but profitless achievement’ (Anon. 1879a: 451).

Cheyne was incensed that Beaumont had dismissed his ideas so freely, and rose from the audience at the end of the address to defend himself against what he saw as a ‘jealous attack’ on his plans. Some applauded, others laughed loudly, a few objected to Cheyne's ‘incendiary’ language, whilst everywhere was chaos. Markham restored order and asked Beaumont to defend himself, and the young officer reiterated his belief that ballooning was ‘impracticable’, and moreover, that ‘he felt it his duty, as one who had so recently been in the Arctic regions, to tell the public so’, pitching the floor into chaos once more. As he had ‘served under Commander Cheyne’, Markham claimed later that he was ‘reluctant’ to speak out, but now, sensing his chance, he rose to offer his presidential verdict. What was needed, he suggested, was careful thought and a dose of realism. A ship was best, and finding an appropriate route for it was the more pressing challenge, rather than being diverted by hopeful ‘speculations’. In perhaps the most public, and damning, criticism of Cheyne's plans so far, and widely reported later in the national press, Markham delivered a killer blow; declaring, ‘that a balloon expedition would be a fiasco and that it would actually do harm to geographical discovery’ (The Times 27 August 1879). Cheyne's dream was shattered.

After humiliation at the British Association, Cheyne immediately returned to London. Although frustrated, and angered, by his treatment in Sheffield he resolved to increase his efforts, and for the following months campaigned vigorously in order to silence the doubters. He arranged interviews with journalists, laid siege to the House of Commons lobbying members to offer their support, and wrote to popular aeronauts and scientists alike, asking for advice. He sent a steady stream of letters to the newspapers, prepared publicity pamphlets detailing the progress of the ‘movement’, and continued to lecture in crowded halls along the south coast of England. He visited the local committees (by now a total of 59 in towns across the country), spurring them on to ‘keep up interest in the spirit of the cause’, and encouraged the ‘London Central Arctic Committee’ to collect more subscriptions in his absence. With the help of some imaginative water-colourists, he created new dissolving views showing balloons ‘floating freely’ to the poles, and he commissioned a new programme of music, providing the words himself: ‘The British ensign folded lies! Symbol of daring enterprise in generations past! / Upraise our flag in Northern skies, and buoyant o'er the glaciers rise, to hold our honour fast!’ (Anon. 1879b; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Northward Ho!, sheet music by Cramer and Co, 1879. Courtesy private collection.

Shortly afterward The Times devoted its first lead article, of many, to the proposed expedition. Recognising that large sections of the public were still very much attached to the romantic image of polar endeavour, the newspaper sensibly remained in favour of continuing with Arctic exploration, but seized the opportunity to draw attention to the ‘obligations’ that this entailed. If a private venture were to collapse in a terrible accident, or go unheard of for a long period of time, the government would find it impossible to avoid having to send out a series of expensive search expeditions, risking further disaster. The nation would have to bear the loss. It was obvious that there should be no repeat of the Franklin saga (The Times 8 January 1880). But this was a general concern, and more pressing were the risks inherent in Cheyne's plans, obvious even now. Large doubts remained unanswered; just how could he summon up a homeward wind from the pole, were it successfully reached, and how exactly did he intend to battle back across the ice, if forced to land at a considerable distance from the ships? ‘The conception of a party of Arctic aeronauts waiting patiently at the Pole for a favouring breeze to carry them back to their companions, and starting off to walk, when their patience is exhausted, would be ludicrous enough if the whole matter were not a very serious one’. The Times advised its readers to withhold their support until the plans had been approved by those who ‘can speak with authority’, namely the RGS and other naval officers with Arctic experience. Here was the challenge that Cheyne, and other aspirant explorers, had to face; a landscape of power and patronage that could advance, or dash, their hopes in an instant. Without the society's approval, and lacking Markham's support, Cheyne's expedition would be unlikely to leave London.

In the run-up to a large Mansion House meeting, scheduled for the afternoon of 28 January 1880, public interest was intense and the London newspapers were full of letters and commentary, with strident criticisms of the ballooning ‘folly’ sharing the pages with rousing petitions in its favour; sparking lively debate on the value of polar exploration itself. The ballooning plans found a wicked critic in Punch, whose writers strongly objected to the inevitable ‘loss of valuable life’, and the ‘waste of valuable money’:

[T]heir plan of Polar attack is literally en l'air, being principally based on ballooning, while their sinews of war are to be contributions raised throughout the English Counties by Local Arctic Committees. If these Polar promoters succeed in raising the wind by such means, Punch is prepared to allow that they may not only reach, but carry off, the North Pole in a Balloon. Punch hates to throw cold water on anything that aims at serving science, and finds a field for pluck, and cold water seems the best thing to fling on a North Pole adventure; but the line must be drawn somewhere. There are limits to Quixotism, even of the scientific or heroic kind; and if they are fixed at latitude 82° North, Punch does not see who would be the worse for such a fixing. A chain is only as strong as its weakest point, and a Cheyne is no stronger (Punch 24 January 1880; Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 ‘Arctic Aeronautics’, caricature from Punch, 1880. Author's collection.

After the excitement of Nares’ safe return had given way to disappointment, a degree of public antipathy had set in, and some people hoped the ‘fresh’ new plans would vivify the nation's polar ambitions. Others were not convinced and, pointing to the plan's naive excesses, were amazed that so many were still won over by the whole romantic notion. Coxwell, for example, wrote to The Times to defend the plan, concerned that the image of ballooning had become distorted in the public mind, and he took time to detail its technical virtues (31 January 1880). Whether blindly supportive, or rightly cautious, most thought it reasonable to give the equipment a trial run in a public demonstration; friends of the project sure that it would silence the doubters, whilst opponents of the scheme looked forward to an embarrassing failure, to stop the debate once and for all. One anonymous fellow wrote to The Times suggesting that before Cheyne and ‘his devoted band of adherents’ started for the pole, they might like to take ‘a preliminary canter’ from London to Edinburgh, landing their balloon on Arthur's Seat: ‘if the experiment were in any way successful, subscriptions in aid of the expedition would, no doubt, flow in abundantly, and I suggest the Crystal Palace, that favoured haunt of science and education, as a starting point. There can be no doubt that many thousands would gladly pay a shilling to see the expedition start, and ten times as many would pay almost anything to see it come back’ (4 February 1880). Aware of the irony, but with an eye to a profit, the manager of Crystal Palace declared that ‘it would be a capital thing’, and he immediately offered his grounds for the trial.

Unsurprisingly, Cheyne was less enthusiastic. At first he let the matter alone, but was soon amazed to find the public set on the idea. He wrote to The Times to urge the public to abandon the thought. It was wholly irregular to make such a demand, he claimed, and equally improper to use subscription money ‘for experiments intended to gratify others’. Coxwell also refused to be forced into making a public demonstration, and with North and Irish Seas yawning for his basket, Cheyne balked at the risks. Not least, he reasonably concluded, it would be impossible to employ the trail ropes, which were a crucial part of his plan for navigating, without sweeping through towns ‘cutting down people right and left, severing telegraph wires, and causing serious accidents alike to people, property, and to the balloons themselves’ (The Times 11 March 1880). As the short London summer approached, his plans were beginning to lose momentum. Of the hoped for £30,000, only £2,000 had so far been raised. Considering the support he still received in the provinces, he was puzzled that funds were not forthcoming, and what few monies had been gathered were simply not enough to persuade others to part with their cash: ‘It ought not to be difficult in this wealthy country to collect for such a purpose a sum not greater than is dissipated every night in London in amusement and frivolity’, he wrote (The Times 28 May 1880). Cheyne knew something was needed to grab the public's attention once more, and fast; perhaps ‘amusement’ and ‘frivolity’ were exactly what was necessary.

Cheyne established the ‘Balloon Society of Great Britain’ in 1880, giving a new name to a loose collection of his contacts, in an attempt to breathe life into his enterprise. In May he entered into negotiations with Major Flood Page, the enthusiastic manager of the Crystal Palace, to arrange a trial flight after all; but one that would be on his own terms. His hopes were lifted late in August with the news that the Balloon Society was finally ready to do something practical to promote the effort, by holding an ‘international Balloon Contest’ (The Times 24 August 1880). Late in the afternoon on 4 September eight balloons took to the skies above London; each aeronaut choosing his elevation in order to travel the longest distance possible in one hour and a half. A journalist was assigned to each balloon, and the man from The Times eagerly took his place alongside Cheyne in the Owl departing from Crystal Palace. Mr Wright, the pilot, eased the balloon into the air before a large crowd of onlookers, taking a course toward the northeast, as Cheyne busied himself with meteorological measurements. Passing high above the Thames docks, they soon left the river behind them, floating gently over the meadows of Essex. The landing was less serene, narrowly avoiding some telegraph wires before bumping to earth in a barley field, some 42 miles (68 km) from London (The Times 6 September 1880). The following evening all the balloonists gathered at the Charing Cross Grand Hotel to discuss their adventures. Taking the stage that evening, Cheyne campaigned once more for a return to the north, and the newspapers echoed in support.

But it would not be long before his hopes came crashing to earth. It was becoming clear that although exhibitions, lectures, and balloon spectacles did much to raise the profile of the proposals, and keep them before the public in the newspapers, there were many that still remained unsatisfied. Without official support, Cheyne knew that it would be impossible to persuade sufficient numbers of people that his plans were credible, and achievable, and thereby enabling him to gather together the required funds. On 22 November therefore, the Central Arctic Committee laid a statement of their proposed scheme before the Council of the RGS. By this time Cheyne's plans had been ‘refined’ down almost completely, and all that seemed left was vague speculation. It was as if the energy had run out of the proposals; what had once been spectacular, headline grabbing, and inventive, now reduced by common sense conservatism, was drab and uninspiring. Provided with a small steam launch, materials for a hut, boats, sledges and provisions for three years, Cheyne and a party of men would head north to St. Patrick's Bay (near the winter quarters of Discovery) sailing in the spring of 1881 as passengers on a Dundee whaler. Natives and dogs were to be picked up ‘at the Greenland settlements’, and a few balloons were to be taken for observational purposes. The following spring, Cheyne's party would reach the pole dragging boats over the ice. The RGS Council wasted little time in considering the plan, and their rejection, dated the following day and widely reported by the press in the weeks that followed, probably marked the end of any hope that Cheyne would find support for his plans in England (The Times 6 December 1880).

William Keppel, Under-Secretary for War, and a long-time supporter of exploration, also denounced Cheyne's plans in the strongest terms. Launching a prolonged attack in the pages of The Quarterly Review, Keppel was sure that Cheyne's ‘vision’ for flight was nothing more than a ‘reckless’ speculation. Ignoring ‘the very ABC of Arctic exploration’, he declared, Cheyne's plans could only spell disaster:

The man who rashly rejects the stored-up wisdom of a host of predecessors is not properly described as adventurous, but as unwise. . .this is not enterprise, but foolhardiness. . .Let the poor sailors at least be told that the expedition is one in which, humanly speaking, success is almost impossible, and in which failure means certain and terrible death (The Quarterly Review 1880: 125–26).

Yet, Keppel was most concerned by what he saw as an assault, not on the pole, but on the ‘tradition’ of naval expeditions of the past, and the ‘image’ of exploration itself. Sledge travel and man hauling were key features of this tradition, ‘reduced by Osborn and McClintock to a science’, which provided the Navy, and the government, with inspirational images. On the other hand, Keppel decided, a private ballooning voyage ‘puffed into notoriety’, and lacking naval discipline, would certainly fail. Although the failures of the man hauling technique had been well demonstrated by the Nares expedition, Keppel demanded that its ‘virtues’ be protected: ‘There is nothing in the naval story more striking than the pertinacity with which those gallant men struggled on, with their sledges laden’. Daring to offer an innovative technique of travel, Cheyne was facing obstacles that he would be unable to cross. Rejected by the RGS, ignored by the Admiralty, and deserted by many of his initial supporters, Cheyne's campaign in Britain was over.

In a final bid to raise support for his venture, Cheyne left England for America. He arrived in New York on 16 November, after an eventful voyage across the Atlantic through a hurricane (The New York Herald 17 November 1881). The following day, Cheyne delivered the first of three illustrated lectures before an enthusiastic audience at the Chickering Hall. His lecture was entitled, ‘Baffled, Not Beaten; or, The Discovery of the Pole Practicable’, and took the form of an imaginary voyage. Patching together forty ‘vivid and spirited pictures’, Cheyne took his audience toward the pole, ‘illustrating the various difficulties, dangers, and rewards’ (The New York Herald 18 November 1881). In a final flourish, portraits of Victoria and President Garfield were projected upon the screen, coupled with a sketch that he had hastily worked up himself showing allegorical figures of Britannia and Columbia supporting a crown over the head of the late President, and he appealed for help to launch a new ‘Anglo-American Expedition’.

On 21 November he delivered his second lecture ‘Five Years in the Arctic Regions: The Search for Sir John Franklin’, a dramatically constructed account of his previous service in the Arctic, with a number of slides showing him braving the ice. Aware that public sympathies were looking toward the north for news of the missing expedition of George Washington de Long, Cheyne realised that it was to his best advantage to combine a search with his own project. He now declared that he had arrived in the country to mount an expedition to ‘offer assistance to the steamer Jeannette’ (The New York Times 22 November 1881). A few days later, he gave as his final performance a new lecture, ‘The Ocean and its Wonders’, with an assortment of ‘stereopticon views’ of coral and sponges, marine animals, and dramatic shipwrecks dancing across the canvas screen (The New York Times 25 November 1881).

On 28 November Cheyne appeared before the New York Academy of Sciences. With the hall at 12 West Street ‘filled to overflowing’, the President John Newberry rose to support the scheme: ‘His plan is not chimerical, and is certainly heroic. Men will yet surely go to the Pole, if they have to crawl there on their hands and knees; and an enterprise of this kind is worthy of attention in these days, if only to withdraw the minds of men from their shops and money-getting and purely selfish occupations’ (New York Tribune 29 November 1881). Cheyne then delivered his ‘Discovery of the North Pole Practicable’ lecture, once again suggesting that he would attain the pole by triple balloon, as well as making a number of attempts by sledge. Free from the scrutiny of the RGS, and aware of its ability to grab public attention, Cheyne resurrected the balloon plan. His budget had now dropped to £16,000, half of which he hoped would be provided by a ‘generous’ American public. After another show of hands, and some hearty applause, the hall soon emptied. Another meeting had ended, yet with few tangible results (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 Illustrated lectures and the visual culture of exploration, programme for 1881. Courtesy private collection.

In the weeks that followed he continued to write to the newspapers and to lobby prospective supporters, sallying forth from his rooms at the Lotus Club to give lectures to school groups and anyone else willing to pay for the privilege. In early December he travelled south to perform in towns in New Jersey. Meanwhile, the public continued to look to the north, waiting for news of de Long. In June 1881, the same month that Jeannette was crushed in the ice north of Bering Strait, a relief expedition, also sponsored by newspaper magnate James Gordon Bennett, had been sent out under Lieutenant Robert M. Berry. However, his ship, the USS Rodgers, caught fire in St Lawrence Bay in eastern Siberia, leaving its survivors in a desperate condition. The New York Herald's journalist on the voyage sledged almost 2,500 miles across northeast Siberia to telegraph the news. By December word of the Jeannette's dramatic failure had also reached the nation. Though it made for thrilling newspaper copy, an expectant public were horrified by the tragedy; sensational news was soon followed by bitter charges and debates.

Enthusiasm for the Arctic was at an all time low. In this context of recrimination and national loss, it is no surprise that Cheyne found it difficult to recruit support for a new Arctic venture. If only for a moment, the American public were united in believing that there should be no repeat of the Jeannette disaster, for the risks now seemed too great. To add another tragedy to the ‘desolate pages of Arctic exploration’ was simply too much (The New York Times 21 December 1881). Undaunted, Cheyne followed up a series of interviews by continuing to write long letters to the press. On 23 December he started for Canada via the Central Railway. While jostling in the carriage en route to Toronto, he wrote again to the Editor of The New York Herald, requesting that the newspaper open up an ‘Arctic Fund’ to collect the money he required. This letter, it is safe to say, brought things to a head. The New York Herald declined, and published a caustic reply in its pages soon afterward:

Mr. Cheyne's scheme strikes us as visionary in the most extravagant degree. Ballooning, after a very large number of experiments made in all sorts of circumstances, is so uncertain a method of locomotion that its operations are absolutely without safety or certainty for any purpose whatever. . .To suppose that what cannot be done with safety and success in England, France, or the United States, can be performed with perfect order and satisfactory results in the unknown wastes of sea and ice - with perhaps unknown atmospheric conditions added to the other difficulties - goes beyond the limits of reasonable theory. It seems to us not in the best taste for Mr. Cheyne to propose this wild attempt just now when one of his countrymen, Mr. Leigh Smith, is perhaps in urgent need of help. If the Herald should open at this time any subscription for Arctic objects it would be to the rescue of the gallant Englishman who has gone exploring in a business-like and plucky way instead of running about the world with a visionary scheme in hand and a few lectures in his pocket (The New York Herald 28 December 1881).

The reference to Benjamin Leigh Smith in the above relates to his expedition to Zemlya Frantsa-Iosifa [Franz Josef Land] in Eira. His ship was crushed and his crew was forced to over winter at Mys Flora [Cape Flora]. It is probable that this public rejection turned the tide of opinion firmly against Cheyne. The New York Times carried a long article the following day, further condemning the ‘folly’ of his proposals. Considering the ‘total loss of money’ invested in the Jeannette expedition, and the ‘incredible suffering’ of her crew, a new Arctic voyage was, in the words of the paper, wholly ‘immoral’ (The New York Times 24 December 1881).

On 17 January, Cheyne headed across to Ottawa. He reported to the press that had ‘received hearty support from political parties of all shades’, and that he expected to be soon awarded a government grant for his expedition (The New York Times 18 January 1882). The basis for this optimism was his knowing Sir Leonard Tilley, then Minister of Finance for Canada. A Free Press journalist, interviewing Tilley in Ottawa in 1882, managed to draw from him an assessment of the plan: ‘I have my own doubts as to its feasibility. I think it probable that he will try to interest Parliament in the scheme and endeavour to obtain a vote of money from it, but I am not so sanguine about his success in that direction’ (Uxbridge Journal 12 January 1882). Tilley was right to have his doubts. The vociferous criticism of the American newspapers had proved too much, and Cheyne was unable to attract any more interest in his plan. All told, his trip to North America in search of support had been an unmitigated failure. He did not return to New York, but stayed with his sister in Canada, no doubt licking his wounds. His reputation was in ruins. It is possible that he never returned to England. Since 1876 he had been on the road promoting his vision of flight, and though he found wide support he had also faced almost constant ridicule. Perhaps long overdue, it was now time for Cheyne to take a final bow, pack away his lantern, fold up his notes, and step out of the limelight. The dream of polar flight, for now, was over.

Though many had been entertained by his lectures, his itinerant campaigning had ultimately cost him his marriage, and in England his plans were long forgotten. In the intervening years many others dared to propose a voyage north in a balloon and, like Cheyne, they risked ridicule and condemnation in the process. In 1890, for example, two young Frenchmen, Besançon, an aeronaut, and Gustave Hermite, an amateur astronomer, advocated a polar flight, publishing details of their plans in the illustrated press. Naming their balloon Sivel, in honour of a ‘martyr de la science aéronautique’, who had died in a high altitude attempt, they planned to ascend from Spitsbergen and head straight for the pole, whilst reconstructing a chart of the Arctic with a series of aerial photographs taken through the floor of their elaborate wicker capsule. A series of vivid illustrations of their imagined voyage, which could easily have leapt from the pages of an adventure novel, may have captured youthful enthusiasms for a moment, but this was not enough to attract the funding required to turn the voyage into a reality (L'Illustration 1 November 1890; The New York Times 6 December 1890).

In 1895 a Russian engineer named Serge de Savine proposed a crossing of the pole in a double balloon with suspended heating apparatus, but he too was unable to raise sufficient support for his project (The New York Times 24 August 1895). Salomon August Andrée arrived in London that summer and announced his plans for an airborne assault on the pole. When challenged by a sceptical newspaper reporter, the Swede was indignant. ‘No, I don't see that there will be any dangers at all’, he declared, ‘for I have every confidence in the success of my enterprise, and am sure that before long I shall find any amount of imitators. I do not care a snap of the fingers what my critics say, for I have got the money, and nothing can prevent me starting now. There is no doubt whatever about it’ (The New York Times 1 September 1895).

It is safe to guess that Cheyne would have also followed this succession of aerial proposals in the newspapers, though we have no record of his opinions on the subject during these years. Indeed, the lack of documentary evidence makes it difficult enough to track him down. We do know that he was still lecturing on ballooning however, despite his project being rejected so many years before. In 1891, for example, at the ripe age of 64, he gave one such lecture to the residents of Hamilton, regaling his audience with grand plans for a triple balloon flight to the pole, with sleighs acting as baskets trailing ropes made of piano string wire (Hamilton Daily Republican 20 February 1891). From his long experience of Arctic travel ‘no other could be more qualified to find the North Pole’ Cheyne concluded, asserting his priority of vision by proclaiming that he had conceived the balloon route as early as 1853. Although the years may have clouded his memory, this eccentric man had certainly lost none of his conviction.

Conclusions

On the clear morning of 4 February 1902, just a few days before Cheyne passed away in his Halifax home, the first balloon to be launched in Antarctica rose skyward above the Ross Ice Shelf. At an elevation of 800 feet (244 m), its pilot, Captain Robert Falcon Scott, reached for his telescope to view the great barrier of ice stretching out beneath him, toward mountains far in the distance, and beyond that the invisible mysteries of the South Pole:

The honour of being the first aëronaut to make an ascent in the Antarctic Regions, perhaps somewhat selfishly, I chose for myself, and I may further confess that in doing so I was contemplating the first ascent I had made in any region, and as I swayed about in what appeared a very inadequate basket and gazed down on the rapidly diminishing figures below, I felt some doubt as to whether I had been wise in my choice (Scott Reference Scott1905: 198–99).

Ernest Shackleton bravely went up next, armed with a camera, and then descended to join the other officers in celebrations aboard Discovery (Shackleton Reference Shackleton1903). Edward Wilson, the ship's assistant surgeon, declined the chance to take a flight after lunch, before deteriorating weather (and a rent in the balloon) put stop to the operations. Writing candidly in his private journal later that evening, he doubted the general sanity of polar ballooning: ‘I must say I think it is perfect madness to allow novices to risk their lives in this silly way, merely for the sake of a novel sensation, when so much depends on the life of each of us for the success of the expedition. . .if some of these experts don't come to grief over it out here, it will only be because God has pity on the foolish’ (Wilson Reference Wilson1966: 111). This was a reasonable assessment: Shackleton had merely three days instruction, Scott none at all. It was later discovered that the balloon's valve was faulty and had either man used it that morning ‘nothing could have prevented the whole show from dropping to earth like a stone’. The history of polar exploration could have been rewritten in a moment, in the ‘very inadequate basket’ of a balloon. No further ascents were made during the National Antarctic Expedition; the risk was too great.

Compared to Scott and Shackleton, Cheyne was no ballooning novice, yet his vision of polar flight was grounded by similar misgivings: risk, expense, unreliability, and ballooning's continuing reputation as a frivolous sensation. Whilst the spectacle of an airborne assault of the pole was undoubtedly appealing, immediately capturing the interest of show-going audiences, the winds of public favour were fickle. Public enthusiasm for the venture waned, and once closer scrutiny had been focused on his proposals by those who had been approached to consider offering funding or support, it became clear that any possible benefit of reaching the pole could not justify the considerable risks.

It is useful to look at expeditions that never happened, and ask why this was the case. They can reveal much about the culture and politics of exploration in this period: of hopes and fantasies, of rising enthusiasms and bitter failures. Within a vibrant public culture of performance explorers took to many stages, and different images of the idea of exploration competed before a wide range of audiences. As imaginations soared, some looked to ballooning as the ideal means of surmounting the difficulties which barred progress to the pole, yet many more were appalled by the recklessness of such an attempt. Despite constant effort on his part, with appealing visions of the Arctic flickering by limelight in crowded lecture halls on both sides of the Atlantic, Cheyne was unable to attract the financial support necessary to realise his dream of polar flight.