Introduction

Religious texts comprise the bulk of works composed in the newly emerging literary language of Anatolian Turkish in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. These texts have been studied primarily by Turcologists interested in philological and lexical data, but have seldom been examined in the context of the wider Islamic tradition, or with attention to larger historical, socio-cultural, intellectual and institutional developments. The use of the Turkish vernacular by the authors of these texts was motivated by the growing need among Turcophone Muslims for basic literacy in the Islamic textual tradition. In addition to the corpus of mystically oriented works, such as hagiographies of celebrated Sufis, mystical verse and rhymed couplets (mathnawīs), and guides for Sufis, texts of religious learning in the Anatolian Turkish vernacular sought to introduce to Turcophone audiences the meaning of the Quran and basic Islamic tenets, beliefs and practices. Many of these early Turkish works are translations and/or adaptations of authoritative Arabic texts, presented in a variety of formats and genres: interlinear translations of the Quran (Arabic text with Turkish word-by-word glosses),Footnote 2 Quran commentaries,Footnote 3 explanations of ḥadīth, and handbooks of law. Turkish translations and adaptations of authoritative Arabic Islamic religious texts often reshaped the original works upon which they were based according to the concerns and perspectives of their Turcophone audience. Vernacularizing and adapting Arabic religious texts according to the needs of their audience constituted an important element in the process of the Islamization of Anatolia and the neighbouring Balkan regions under Ottoman rule.

Devletoğlu Yūsuf Balıḳesrī’s verse Hanafi law manual, written in Anatolian Turkish, is a striking example of the vernacularization of classical Islamic learning in the early fifteenth-century Ottoman realm. Dedicated to the Ottoman sultan Murad II (r. 823–848/1421–44, 850–855/1446–51), the work reduces the contents of the Wiqāya, a major epitome of the well-known Hanafi manual of substantive law, the Hidāya, to a simplified, easily memorizable verse format of rhymed couplets (mathnawī) in the Turkish idiom. In this study, I argue that Devletoğlu Yūsuf's work is a pragmatic religious text that engages in a complex relationship with the Classical Arabic sacred textual tradition. Often described as a translation of the Wiqāya, in fact, the text loosely paraphrases the Wiqāya tradition, conveying the essentials of Hanafi law. I examine several passages from one section of Devletoğlu Yūsuf's work, the “Book on Judicial Procedure” (Kitābu'l-Ḳażāʾ)Footnote 4 with special attention to the inclusion of new material. The author locates the work at the centre of the Ottoman Empire by adding a theoretical law case set in the Thracian towns of Yanbolu and Edirne. I also analyse Devletoğlu Yūsuf's extensive prologue, the sebeb-i telīf, or “reason for composition”, in which he discusses the benefits of transmitting religious knowledge in the vernacular and justifies the use of the Turkish vernacular for Islamic learning by drawing on Hanafi-approved Persian practices of religious devotion and notions of rhetoric and grammar elaborated by the eleventh-century Classical Arabic grammarian ʿAbd al-Qāhir al-Jurjānī (d. c. 471–474/1078–81).Footnote 5

Devletoğlu Yūsuf's law manual and the Hidāya-Wiqāya tradition

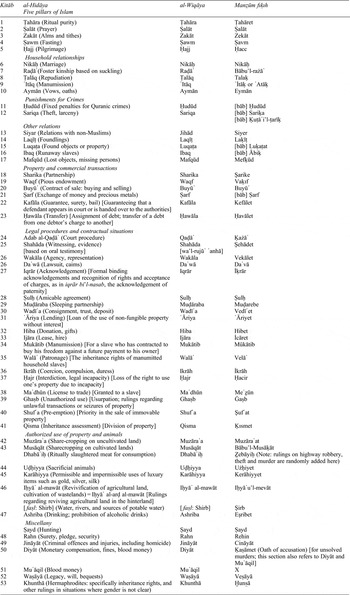

We know almost nothing about Devletoğlu Yūsuf other than the information he provides in his Turkish law manual. At the age of 28 in the year 827/1424, he composed the work and dedicated it to Murad II in an effort to gain favour at court.Footnote 6 Curiously, since Devletoğlu Yūsuf did not specify a title for his work, it has been given a variety of titles by Ottoman copyists, readers and librarians, e.g. Terceme-i Viḳāye, Viḳāye tercümesi, Kitābu'l-beyān, Murād-nāme and Manẓūm fıḳıh;Footnote 7 for convenience, I refer to it as Manẓūm fıḳıh (versified fiqh). The work survives in at least 70 manuscript copies, which suggests a fairly wide readership. Despite its common designation as Terceme-i Viḳāye or Viḳāye tercümesi (translation of the Wiḳāya), Devletoğlu Yūsuf does not refer to his work as a translation nor does he make any reference to the Wiqāya.Footnote 8 Indeed, the Manẓūm fıḳıh greatly resembles the Wiqāya, employing the same standard organizational format (see Table 1) and imparting more or less the same legal information. It nevertheless includes passages not found in the Wiqāya, suggesting that Devletoğlu Yūsuf was more an author-compiler than translator.Footnote 9

Table 1. Chapter headings of the Hidāya, Wiqāya, and Manẓūm fıḳıh

Devletoğlu Yūsuf's Manẓūm fıḳıh may be situated within an authoritative Hanafi tradition of law that had developed over several centuries in Transoxania, standardized in Burhān al-Dīn ʿAlī al-Farghānī al-Marghīnānī’s (d. 593/1197) al-Hidāya fī Sharḥ al-Bidāya (Guidance in the Commentary of the Bidāya).Footnote 10 A basic manual of Hanafi rites, observances, and law, the Hidāya has remained a central legal text for Hanafis until the present.Footnote 11 The Hidāya was widely commented upon,Footnote 12 and its reception in the Ottoman empire is well attested. According to the seventeenth-century Ottoman bibliophile Hājjī Khalīfa (Kātib Çelebī, d. 1067/1657), the Hidāya should serve as the Muslim's principle guide through life.Footnote 13

The Hidāya is a fairly concise fiqh text, comprising two to four large volumes in modern printed editions.Footnote 14 For reasons of economy and utility, lower-level madrasa students needed brief synopses and radically abridged versions of the work, shorn of jurisprudential discussions and chiselled down to a set of laws suitable for memorization and easy reference – hence, the great popularity of Burhān al-Sharīʿa Maḥmūd's Wiqāya al-riwāya min masāʾil al-Hidāya (The Trusted Narrative on Issues in the Guidance)Footnote 15 which, in turn, spurred a large number of commentaries and glosses.Footnote 16 Composed in the thirteenth century by the Bukharan scholar, Burhān al-Sharīʿa Maḥmūd,Footnote 17 the Wiqāya is a digest of selections from the Hidāya designed to assist the beginning student in studying and understanding the authoritative text upon which it is based by presenting laws and rulings in a simple-to-consult format designed for easy memorization.Footnote 18 The Manẓūm fıḳıh was composed with similar pedagogic aims in mind.

The Manẓūm fıḳıh and classical Hanafi substantive law in the early Ottoman context

Although the Manẓūm fıḳıh follows the same format as the Wiqāya and Hidāya, and largely reproduces the same juridical points, it sometimes does so in quite a different manner, and not only because of the syntactic and semantic constraints imposed by its format of rhyming verse couplets. In the book of judicial procedure (Kitābu'l-Ḳażāʾ), which treats the post and conduct of the qadi,Footnote 19 Devletoğlu Yūsuf illustrates abstract legal points with concrete examples not found in the Wiqāya. These examples provide a local context for his intended audience, which may have been Turcophone children studying at the maktab, where they were introduced to the basics of fiqh before having acquired enough Arabic to read the standard textbooks.

Devletoğlu Yūsuf prefaces the section on judicial procedure with a statement on the hierarchical relationship between rulership, the post of the qadi, and the carrying out of justice according to the sharīʿa:Footnote 20

These remarks are not found in the original text of the Wiqāya composed in Bukhara in the thirteenth century, but are unique to Devletoğlu Yūsuf's fifteenth-century Turkish text, and impart the author's particularly Ottoman understanding of the relationship between the ruler and the qadi. Although since early Abbasid times the ruler (whether caliph or sultan) or his representatives were responsible for appointing qadis,Footnote 26 the intimate association of the qadi with the sultan appears to be a new historical development. Guy Burak has recently argued that a major change occurred in the nature of Islamic law in the eastern Islamic lands in the post-Mongol period. Burak points out that in the Sunni successor states of the post-Mongol lands, such as the Ottomans, Timurids and Mughals, a new relationship emerged between the ruling dynasty and Islamic law: ruling dynasties attempted to regulate the structures, doctrines and authorities of law schools.Footnote 27 Islamic law was no longer the sole province of jurists, free from intervention by political rulers, but rather became closely tied to the prerogatives of a sultan, and in turn constituted an important element of dynastic and political legitimacy.Footnote 28 Devletoğlu Yūsuf's insertion of the sultan into his text – with an emphasis on the sultan's intermediary role between God and the implementer of God's law, the qadi – indeed reflects the above changes described by Burak in the ideology and practice of Islamic law.

The bulk of the chapter on Ḳażāʾ contains the same legal precepts and principles mentioned in the Wiqāya. Thus, we are told that a qadi should be knowledgeable, and preferably a scholar who has attained the status of müctehid (Ar. mujtahid),Footnote 29 that is, a jurist authorized to use independent legal reasoning (ijtihād);Footnote 30 in the post-classical period, a qadi who held the rank of mujtahid fī’l-madhhab was required to be capable of making judgments based on the established rulings and opinions of his school. Devletoğlu Yūsuf writes:

Devletoğlu Yūsuf's discussion of a qadi's ethical behaviour also closely follows the Wiqāya. He says:

These verses on the characteristics and ethical behaviour of a qadi, as well as where he may hold court, faithfully summarize the contents of the Wiqāya.Footnote 40 Devletoğlu Yūsuf diverges significantly from the Wiqāya in a subsection (bāb) of this chapter dealing with the impermissibility of using written correspondence between qadis (kitāb-i ḥukmī) as evidence for reclaiming lost movable property.Footnote 41 Rather than explaining the regulations, Devletoğlu Yūsuf introduces a hypothetical case involving the loss of a horse by someone residing in the Thracian town of Yanbolu.Footnote 42

These verses explain that the admissibility of judicial letters of evidence (kitāb-i ḥukmī) is limited to cases involving immovable property for, as the Hidāya more fully explains, only immovable property may be defined by a description of its boundaries – whereas movable property must be physically exhibited at court.Footnote 51 Here Devletoğlu Yūsuf uses a concrete example to ease the beginner student's introduction to the complexities of law. By referring to Edirne, the Ottoman capital, and the Ottoman Balkan town of Yanbolu, Devletoğlu Yūsuf also imparts local colour into the text. Devletoğlu Yūsuf probably created the case for pragmatic pedagogical purposes: qadis regularly dealt with the recovery of lost horses and other livestock.

Aside from an occasional interpolation as in the above example, the Manẓūm fıḳıh closely paraphrases the Wiqāya, sometimes verbatim. Curiously, Devletoğlu Yūsuf is silent with regard to his work's intimate relationship with the Wiqāya. He does, however, cite as sources eleven other authors and texts, belonging primarily to the Transoxanian Hanafi tradition, such as the Muḥīṭ al-Burhānī by Burhān al-Sharīʿa (d. 616/1219).Footnote 52 He also notes in his preface that he made limited use of material from fatāwā works which he does not identify.Footnote 53 Devletoğlu Yūsuf emphasizes the legal authority of the three leading Hanafi jurists: Abū Ḥanīfa (d. 150/767), the eponymous founder of the Hanafi school of law; his foremost disciple, Abū Yūsuf (d. 182/798),Footnote 54 who is often referred to in the text as the “Second Imām” (İmām-ı Sānī); and their student, Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasan b. al-Shaybānī (d. 189/805), simply called Muḥammad as is customary in classical Hanafi judicial literature.Footnote 55 Devletoğlu Yūsuf specifies that his work is an explication of the Hanafi school of law as found in the rulings of the two Imāms, i.e. Abū Ḥanīfa and Abū Yūsuf.Footnote 56 And, to remind his audience, presumably young readers, of the three founders of Hanafism, Devletoğlu Yūsuf refers to them throughout the work using the following formula in myriad variations: “this is Abū Ḥanīfa's, Abū Yūsuf's or Muḥammad's position” (ḳavl, from the Arabic qawl, literally, word).Footnote 57 At the end of his work, Devletoğlu Yūsuf emphasizes Abū Ḥanīfa as his primary source and authority, highlighting his eminence as imām and mujtahid:

Thus, rather than associating himself with his main source, the Wiqāya, Devletoğlu Yūsuf locates his textual authority with the aṣḥāb al-madhhab, the founding fathers of the Hanafi school – Abū Ḥanīfa, Abū Yūsuf and Muḥammad al-Shaybānī, presenting them as the primary mediators between the Word of God and the wider public of believers.

Justifying the vernacular: Devletoğlu Yūsuf's prologue

Devletoğlu Yūsuf's decision to compile a Hanafi legal handbook in Anatolian Turkish verse needed not only explanation but also justification, on both cultural and religious grounds.Footnote 59 Like other fifteenth-century Ottoman authors writing in Turkish, Devletoğlu Yūsuf prefaces his Manẓūm fıḳıh with a self-conscious statement justifying his use of Turkish for imparting religious knowledge usually rendered in Arabic. With respect to vocabulary and expression, Anatolian Turkish was at a disadvantage compared to Arabic and Persian.Footnote 60 Anticipating detractors, authors in the Turkish vernacular offered justifications for their choice of language, usually arguing that they were serving the common good by making knowledge accessible to those otherwise denied its benefits. In his prologue, Devletoğlu Yūsuf offers a detailed and sophisticated argument for the use of Turkish.

Devletoğlu Yūsuf begins his preface with a pragmatic argument. The use of Turkish, he claims, is necessary for the edification of Turkish readers not proficient in Arabic. He then cites the precedent of religious scholars who composed in Turkish:

Although these earlier authors often offered apologies for the use of the vernacular (ʿöẕrini hem anda ḳıldılar beyān),Footnote 62 this was not because they were ashamed to use Turkish (hem idenler daḫı hiç ʿār etmedi).Footnote 63 Rather, Devletoğlu Yūsuf suggests, these apologetics were nothing more than conventional literary topoi. Indeed, these authors were motivated by the desire to serve the people (ḫayr-ı nās olmaḳ dilediler hemān)Footnote 64 by providing them with access to knowledge that was otherwise inaccessible. By acknowledging the long-standing prejudice against Turkish as a literary medium, specifically for religious texts, Devletoğlu Yūsuf attempts to put to rest these biases by emphasizing the public benefits of rendering religious knowledge in Turkish.

Devletoğlu Yūsuf presents a two-pronged argument for the use of the written Turkish vernacular. While on the one hand, he refers to Abū Ḥanīfa's position on the permissibility of using Persian instead of Arabic for religious acts of devotion as a way to legitimize his own use of Turkish in the place of Arabic, on the other, he invokes notions of Classical Arabic grammar and rhetoric with a discussion on the superiority of meaning (maʿnā) over utterance or verbal form (lafẓ). Rendering religious knowledge in the Turkish vernacular, argues Devletoğlu Yūsuf, reveals meaning otherwise obscured: thus “meaning becomes unambiguously clear” (yaʿnī maʿnā fehm olur bī-iltibās),Footnote 65 like that of “lifting the veil off the face of meaning” (maʿnā yüzinden götürdiler nikāb).Footnote 66 Devletoğlu Yūsuf claims that his vernacular work thus transcends the limitations of mere words or utterances (alfāẓ), and renders into Turkish the meaning (maʿnā) located in the linguistic medium of Arabic. In this context, Devletoğlu Yūsuf plays upon the meaning of naẓm, which refers not only to verse, but also to composition or construction, in the sense of the arrangement of words into a meaningful order.Footnote 67

Devletoğlu Yūsuf's use of naẓm echoes theories of Arabic rhetoric originally developed by Abū Bakr ʿAbd al-Qāhir al-Jurjānī (d. 474/1078). Al-Jurjānī succinctly summarizes these theories in his Dalāʾil iʿjāz al-Qurʾān, pointing out that “stylistic superiority resides in the meanings or ideas (maʿānī) of words and how they are associated with each other in a given composition (naẓm), and not in the utterances or words (alfāẓ) themselves”.Footnote 69 Drawing on al-Jurjānī’s theory of rhetoric, Devletoğlu Yūsuf highlights his own poetic skills, which successfully render the maʿnā of the Arabic tradition into a Turkish composition produced according to the correct conventions of versification:

Fifteenth-century Ottoman scholars were familiar with al-Jurjānī’s theories as developed by the master of Arabic rhetoric, Sīrāj al-Dīn al-Sakkākī (d. 626/1228), author of the Miftāḥ al-ʿulūm, a digest of al-Jurjānī’s two major works on rhetoric and grammar, Dalāʾil al-iʿjāz and Asrār al-balāgha. Al-Sakkākī’s Miftāḥ spurred a flurry of epitomes and commentary-writing in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. For instance, Khaṭīb al-Qazwīnī’s (d. 739/1338) Talkhīṣ al-Miftāḥ fī’l-ʿilm al-balāgha presents a summary al-Sakkākī’s Miftāḥ al-ʿulūm. His Talkhīṣ al-Miftāḥ in turn was expansively commented on by al-Taftāzānī (d. 792/1390) in his Sharḥ Talkhīṣ al-Miftāḥ.Footnote 71 Muṣliḥuddīn Muṣṭafā Ḫocā-zāde (d. 893/1488), the muftī of Bursa, subsequently produced a gloss on al-Taftāzānī’s commentary on al-Qazwīnī’s summary of the Miftāḥ. Ḫocā-zāde's work is one example of the wide interest among fifteenth-century Ottoman scholars in Arabic grammar and rhetoric as established by al-Jurjānī and reworked by al-Sakkākī.Footnote 72

Devletoğlu Yūsuf concludes his discussion of maʿnā and naẓm by pointing out that the use of verse and Turkish are both legitimate forms by which to render religious knowledge:

Why would an author render a legal text, with its dry factual presentation of content, into verse? While such a textual practice seems counterintuitive to the modern mind, which conceives of verse as an imaginal practice, in the pre-modern world verse served multiple functions, especially relating to the internalization of texts when the principal mode of reception was auditory. It has been pointed out that medieval European textual culture, initially shaped largely in a monastic setting, involved the internalization and absorption of texts through memorization.Footnote 74 The literary culture of the Muslim world was also conditioned by memorization and endless repetition of scripture and its exegesis, especially at the elementary level of education. Books thus served as mnemonic devices at the mektep (Ar. maktab) where they were recited and their contents memorized under the guidance of the teacher. The versification of prose religious texts is a phenomenon common to a literary culture where canonical works were internalized through largely auditory means.Footnote 75 It is difficult, nevertheless, to know if a fiqh text, even when rendered into verse to facilitate memorization, was part of the mektep curriculum.Footnote 76 In addition to pedagogical purposes, a shorter versified and memorizable version of a legal manual may have been useful for practising Turcophone jurists, considering the possible difficulties of access to libraries and books, especially in rural areas.

In a reference to madrasa pedagogical practice, Devletoğlu Yūsuf describes a symbiotic relationship between Arabic and the Turkish vernacular. Turkish served as the main language of instruction in madrasas, where students studied the textual tradition in Arabic, even in higher institutions specializing in the instruction of ḥadīth and tafsīr:

Since the oral explication of the Classical Arabic religious textual tradition was customarily done in Turkish, Devletoğlu Yūsuf argues that written Turkish likewise legitimately served as an exegetical language.

Devletoğlu Yūsuf then situates maʿnā within the context of Hanafism. He refers to Abū Ḥanīfa's positive position on the permissibility of the translation of the Arabic sacred text, the Quran:

As reported by al-Shaybānī in his Ẓāhir al-riwāya, Abū Ḥanīfa considered it permissible to read translated portions of the Quran during prayer based on a tradition that Salmān al-Fārisī, one of the Prophet Muḥammad's closest companions, translated the Fātiḥa, the first sura of the Quran, into Persian for use in prayers by Persian Muslims.Footnote 79 By drawing on the precedent of Persian translations of the Quran deemed permissible by Abū Ḥanīfa, Devletoğlu Yūsuf attempts to legitimize Turkish as an “auxiliary” religious language along similar lines to Persian.

Devletoğlu Yūsuf concludes his prologue with reference to maʿnā and lafẓ, thus situating himself in a centuries-old debate over the relation “between alfāẓ as the linguistic expression, and maʿānī as the underlying meaning”.Footnote 80 Devletoğlu Yūsuf aligns himself with al-Jurjānī’s position of privileging maʿnā over lafẓ:

By prioritizing intended meaning over mere verbal utterance – a position which, taken to the extreme, would justify the translation of the QuranFootnote 82 – Devletoğlu Yūsuf thus points out that the actual linguistic medium becomes irrelevant; it is the meaning of the words that counts:

The use of the written vernacular in place of Arabic for exegetical purposes likewise provoked great anxiety in the Islamic world, as exemplified by the late tenth-century Persian translation of al-Ṭabarī’s Arabic tafsīr, the religious permissibility of which was affirmed by a fatwā issued by the ulema of Transoxania.Footnote 84 Yet, despite this anxiety, Travis Zadeh points out that the linguistic leniency shown to new converts with regard to the use of Persian as a religious language in place of Arabic “may have suited the cosmopolitanism of an empire in the process of expanding deeper into Anatolia and Central Asia”.Footnote 85 Indeed, Devletoğlu Yūsuf's constant invoking of the authority of Abū Ḥanīfa and his two disciples serves as a trope for putting to rest the recurrent anxieties associated with the vernacular rendering of religious works usually composed in Arabic.

Conclusion

Devletoğlu Yūsuf presented his work to Murad II in the year 827/1424; this year is significant in that it was by this time that it had become clear that Murad would indeed remain on the throne as the Ottoman sultan after several years of intense warfare in Anatolia against Byzantine-supported contenders.Footnote 86 Indeed, the following two decades of Murad II's reign proved to be a watershed period in Ottoman history for the transference of Perso-Islamic culture to Turcophone Anatolia, with an explosion in the production of literary works primarily through translation and the composition of imitative works. This literary development, as Âmil Çelebioğlu first argued, coincided with Murad II's consolidation of his rule and Ottoman consolidation of its Anatolian and Balkan territories. Devletoğlu Yūsuf's Manẓūm fıḳıh constitutes an early work in a growing trend of Turkish vernacular works patronized by Murad II during the first half of the fifteenth century.Footnote 87

Devletoğlu Yūsuf's Manẓūm fıḳıh likewise provides us with a rare glimpse into the interactive linguistic landscape between Turkish and Arabic in the early religious education of Turcophone Anatolians. Although it would be inaccurate to characterize the work as a translation of the Wiqāya, Devletoğlu Yūsuf did in a certain sense “translate” the Arabic textual tradition of the Wiqāya into the Anatolian Turkish idiom. His translation thus involves not only linguistic movement from Arabic to Turkish, but also the localization of his narrative in his own time and place. This strategy not only made Hanafi fiqh principles more concrete, but also, in essence, indigenized classical Hanafi practice.

In his preface, Devletoğlu Yūsuf justifies his rendering into the newly emerging literary language of Anatolian Turkish, a religious tradition normally composed in Arabic. According to the author, the translation of the Classical Arabic fiqh tradition into the Turkish vernacular finds support in Classical Arabic grammatical–rhetorical theories of meaning and form, as first articulated by al-Jurjānī, combined with the Hanafi precedent of substituting Arabic with Persian as a religious linguistic medium. A law manual drawing on the thirteenth-century synthesis of the Hanafi tradition as it appears in the standard epitome of substantive law, the Wiqāya, Devletoğlu Yūsuf's Manẓūm fıḳıh repeatedly assures its readers that it represents a pure and unadulterated version of the law as first conceived by the three pre-eminent founding fathers of Hanafism. It may well be that Devletoğlu Yūsuf's emphasis on the hermeneutical authority of Abū Ḥanīfa and his disciples related to the anxieties the author faced in translating the Hanafi tradition into Turkish.

Rethinking the emergence of early Anatolian Turkish as a vernacular literary language along broader comparative perspectives and in the context of larger conceptual issues may help us to formulate new questions as well as new methodological approaches for dealing with language and cultural transfer. For instance, what triggers the emergence of a vernacular literary culture?Footnote 88 Observing that “the practices of literary culture are practices of attachment and belonging”,Footnote 89 Pollock proposes that “vernacular literary cultures were initiated by the conscious decisions of writers to reshape the boundaries of their cultural universe by renouncing the larger world for the smaller place, and they did so in full awareness of the significance of their decision”.Footnote 90 In seeking a legitimate literary role for Turkish in the composition of religious texts, authors such as Devletoğlu Yūsuf firmly grounded themselves in the greater Islamic tradition, but translated it into localized versions. Classical Arabic grammar and rhetoric, combined with Hanafi justifications for the use of the vernacular, provide Devletoğlu Yūsuf with the heuristic tools for carving out a smaller yet legitimate space for the Turkish vernacular as a religious textual medium.